Abstract

Firms’ partners often face a wide range of risks and may experience detrimental effects when these firms do not meet certain targets. In this study, we examine how timing of feedback about target outcomes and the presence of incentives for managers to meet these targets influence managers’ effort and their partners’ willingness to collaborate. We test our hypotheses in a representative ESG setting using a multi-period investment game with a 2 × 2 design where a collaborating partner only realises a return on her investment if the manager of the firm with whom she contracts meets an ESG norm. The risk of not meeting this norm decreases when managers provide costly effort. While results show no significant effect of feedback timing on managers’ effort in the absence of incentives, providing incentives to the manager may be detrimental for effort provision when target outcomes become available after a short time period. We also find that in the absence of incentives, firms’ partners invest more when outcomes become available after a short time period than after a longer time period. Further, when outcomes become available after a short time period, partners invest less when managers receive incentives compared to when managers receive no incentives.

1. Introduction

Firms partnering with other firms often face a wide variety of partner risks. Specifically, an important risk is the risk of non-performance (Zeng et al. Citation2022), as firms’ partners may bear severe negative consequences when these firms do not meet certain targets or requirements, including quality and safety requirements, timely deliveries, ethical standards, or prevailing environmental, social and governance (ESG) norms (Hofmann et al. Citation2014, Manuj and Mentzer Citation2008). For example, many firms offshore their production and services to subcontractors. While these subcontractors can deliver effort to increase the likelihood of meeting these types of targets, they may choose not to do so, given that delivering effort is costly (Tang and Tomlin Citation2008). However, not meeting these targets may have serious repercussions, not only for themselves, but also for their partners, often leading to detrimental financial, reputational, and legal consequences (Emmelhainz and Adams Citation1999, Giannakis and Papadopoulos Citation2016, Kim et al. Citation2019, Petersen and Lemke Citation2015).

A notorious example was Theranos, whose partners only found out after years that this startup was not able to meet its performance targets with regard to innovative blood testing technology (Straker et al. Citation2021). Another example was Mattel, who suffered significant reputation losses when one of its suppliers used lead-contaminated paint on Mattel’s products (Gilbert and Wisner Citation2010, Lefevre et al. Citation2010). With regard to ESG standards, Nike had to bear severe consequences when it cooperated with firms that violated child labour regulations (Lim and Philips Citation2008). And Apple, HP, and Dell suffered reputational damage for sourcing electronics from Foxconn, an overseas company which let employees work in hazardous conditions (Bapna Citation2012, Villena and Gioia Citation2020).

We use a partnership setting to examine the circumstances under which firms’ managers deliver higher effort to meet targets that have implications for their partners, which in turn can reduce the risk these partners are exposed to. Because this risk is not under the control of the partners, it is important for them to know when the risk is higher or lower. An important factor with regard to these targets in partnership settings is the timing of feedback about their outcomes, i.e. whether such outcomes become available after a short versus a longer time period. In reality, feedback timing may vary for different reasons. For example, the impact of managers’ effort regarding these targets may become visible over a shorter or longer time period, or firms may decide to measure their performance frequently versus infrequently. Timing of feedback about outcomes towards external stakeholders (among which supply chain partners) may also vary as managers may decide to frequently communicate about their performance and outcomes that are relevant for their partners or infrequently (Aboody and Kasznik Citation2000, Arnold et al. Citation2018). As such, this may affect how fast business partners learn about target outcomes.

This variation in feedback timing is important because prior studies argue that individuals tend to provide less effort when they expect feedback about the outcomes to be provided after a longer time period (Christ et al. Citation2012, Lambert and Agoglia Citation2011, Lewis and Anderson Citation1985, Thornock Citation2016). Further, while effort provided by firms’ managers regarding targets that affect their partners is typically unobservable, partners can receive information on target outcomes through monitoring or by examining disclosures of the firms with which they interact, including annual or ESG reports (Ballou et al. Citation2006, Dhaliwal et al. Citation2011, Hahn and Kühnen Citation2013).Footnote1 We draw on construal level theory (Liberman and Trope Citation1998, Maglio et al. Citation2013, Trope and Liberman Citation2010) to predict that managers may provide lower effort, thus increasing the likelihood that negative target outcomes materialise, when outcomes become available after a longer compared to after a short time period. Partners, in turn, may anticipate lower effort provided by firms’ managers, whereby they are less willing to expose themselves to this partner risk.

Further, we raise the question of how the above effects would change when the firms’ managers receive incentives for meeting these targets. Research on the effect of incentives to meet targets that especially have implications for other parties, including partnering firms, remains scarce.Footnote2 An interesting example of incentives for meeting targets that may not only affect the firm itself, but also its partners and other stakeholders, is the recent and increasingly popular practice of providing ESG incentives to stimulate ESG effort (Brown-Liburd and Zamora Citation2015, Campbell et al. Citation2007, Kolk and Perego Citation2014, Russo and Harrison Citation2005). The evidence on the effectiveness of this type of incentives, however, is inconclusive. We therefore formulate research questions on how this type of incentives affects managers’ willingness to provide effort and whether feedback timing influences this effect. It also remains unclear how firms’ partners react to the presence of such incentives.Footnote3 Overall, we argue that such incentives may signal a lack of effort on the managers’ side. As such, partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk will decrease when incentives are present, especially when target outcomes become available over a short time period.

To test our hypotheses and research questions, we use an investment game with a 2 × 2 between-subjects design with 12 periods of repeated decisions in an ESG setting. This setting speaks to our research setting as not meeting ESG targets may have detrimental effects for the firm’s partners. The investment offers a potential return for both parties (Berg et al. Citation1995, Coricelli et al. Citation2006, Lunawat et al. Citation2021). Important is that whether the investor can realise a return on their investment depends on the manager’s effort to meet the ESG requirement, which is unobservable to the investor. This likelihood increases when the manager expends more effort on meeting the ESG requirement. Our interactive partnership setting allows to capture both the effect of timing of feedback about the outcomes on the effort provision as well as on the partners’ anticipation of this effort provision. We manipulate feedback timing as the time it takes for participants to receive feedback on whether or not the firm met or did not meet the ESG requirement (i.e. after one experimental period in the short time period and after three periods in the long time period). We also manipulate whether or not the manager receives incentives for meeting the ESG requirement.

Results show no effect of feedback timing on effort when incentives are absent. Interestingly, however, incentives, compared to no incentives, lead to significantly lower effort levels when outcomes become available after a short time period, but we find no effect of incentives when they become available after a longer time period. Thus, instead of increasing performance, incentives may backfire, especially when target outcomes are expected to become available after a short time period. We further find that firms’ partners are more willing to expose themselves to partner risk when they expect target outcomes to become available over a short time period and firms’ managers do not receive incentives, compared to when outcomes are expected to become available over a longer time period or managers receive incentives.

With this paper, we contribute to the literature on feedback timing (Casas-Arce, Deller et al. Citation2021, Holderness et al. Citation2020, Lambert and Agoglia Citation2011, Thornock Citation2016). Our study differs from existing studies as we focus on feedback timing in a partnership setting. An important characteristic of our settings is that target outcomes are of interest to partners and stakeholders because they can be severely affected by negative outcomes as these may not only result in financial losses, but also affect their reputation and compliance with laws (Giannakis and Papadopoulos Citation2016, Manuj and Mentzer Citation2008, Zeng et al. Citation2022). The partner can anticipate some of these effects and can react to negative outcomes by reducing investments (Petersen and Lemke Citation2015, Emmelhainz and Adams Citation1999).

We also contribute to the risk management literature. Because subcontracting and offshoring becomes more prominent, firms’ collaborating partners increasingly face a wide range of risks. As these risks may be under control of subcontractors, firms often have no direct information about the risks they are exposed to. It is important to know what factors can at least control part of this risk the partnering firms expose themselves to. Our study provides new theoretical and practical insights, as we show that the timing of providing information to partners and other stakeholders about target outcomes itself may have an impact on effort expended by firm managers and risk borne by partners, depending on whether incentives are provided.

Finally, by studying incentives for meeting targets that may not only affect the firm itself, but also its partners, and how these incentives interact with feedback timing, we also contribute to the recent stream of literature on ESG incentives (Brown-Liburd and Zamora Citation2015, Campbell et al. Citation2007, Kolk and Perego Citation2014, Russo and Harrison Citation2005, Veldman and Gaalman Citation2020). Specifically, our results inform the literature and practice that ESG incentives – and more generally, incentives for the firms’ managers as a solution to reduce partner risk – may have negative unintended consequences, both regarding managers’ effort provision as well as their partners’ willingness to expose themselves to the partner risk. This is particularly the case when feedback about target outcomes is provided after a short time period.

Overall, our results suggest that when firms have the choice, it is optimal, both for the firms as for their partners, that firms provide feedback about target outcomes over a short time period compared to a longer time period and do not provide incentives for their managers to meet these targets. Partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk is higher under these circumstances, compared to providing feedback over a longer time period and/or providing incentives. Providing feedback over a longer time period (with or without incentives) seems to lead to similarly high effort levels as providing feedback over a short time period without incentives. However, given that increased transparency by providing feedback over a short time period is beneficial for partners, we argue that also from the perspective of effort, feedback over a short time period without incentives is optimal. When feedback has to be provided over a longer time period, we find no differences between providing incentives versus no incentives.

2. Literature review and development of hypotheses

2.1. Risk in partnership settings

These days, many organisations offshore production to firms either domestically or overseas. However, firms partnering with other firms may be exposed to non-performance risks (Emmelhainz and Adams Citation1999, Petersen and Lemke Citation2015, Rajashekharaiah Citation2012, Zeng et al. Citation2022). Specifically, firms’ partners may bear significant reputational damage and financial losses when these firms do not meet certain targets or requirements, such as quality and safety requirements, timely deliveries, ethical standards, or prevailing ESG norms (Foerstl et al. Citation2010, Hofmann et al. Citation2014, Giannakis and Papadopoulos Citation2016, Manuj and Mentzer Citation2008). While these firms can deliver effort to increase the likelihood that targets are met, they may choose not to do so, given that delivering effort is costly (Tang and Tomlin Citation2008).

There are many examples of such risks. Not only companies like Mattel, Nike, Apple, HP, and Dell were hurt by their suppliers not meeting certain requirements (Bapna Citation2012, Gilbert and Wisner Citation2010, Lefevre et al. Citation2010, Lim and Philips Citation2008, Villena and Gioia Citation2020). Also dozens of European poultry farms were affected in 2017 when suppliers of cleaning agents used fipronil, a prohibited detergent. As a result, they had to temporarily shut down and millions of eggs were recalled (Lauran et al. Citation2020). Another example where stakeholders and collaborating partners (e.g. Magna) were severely affected is the Volkswagen emission scandal (Shepardson Citation2017, Newman Citation2015). Similarly, when in 2013 the Rana Plaza garment factory complex in Bangladesh collapsed, pressure grew for retailers such as Primark and Walmart to take responsibility (Reinecke and Donaghey Citation2015).

In many cases, firms have some control over the risks that they expose themselves and their partners to. For their partners, however, the effort that managers of these firms provide is difficult to observe through monitoring. Nevertheless, partners can still receive information on target outcomes through monitoring or by examining public disclosures of the firms with which they interact, including annual and ESG reports (Ballou et al. Citation2006, Dhaliwal et al. Citation2011, Hahn and Kühnen Citation2013). This information might become available after a short or a longer period of time. In this paper, we use a common partnership setting where partner risk may have detrimental effects on firms’ partners and examine under which conditions 1) managers are more likely to deliver effort to meet these targets, and 2) partners are more willing to expose themselves to partner risk. Specifically, we examine how effective the recent practice of providing incentives is in a partnership setting, while taking into account the timing of feedback of target outcomes.

2.2. Incentives

To stimulate effort with regard to targets that may affect firms’ partners, firms may provide incentives to their managers. An interesting example of this type of incentives are ESG incentives, where managers receive bonuses based on the firm’s ESG performance. More than a decade ago, pioneering firms such as Alcoa, Intel, and Danone started the trend, and many other firms since then followed (Campbell et al. Citation2007, Ioannou et al. Citation2016, Kolk and Perego Citation2014, McCullough Citation2014). Research on the effectiveness of this type of incentives, however, remains scarce. With regard to ESG incentives, we know based on archival and survey results that incentives may lead to better ESG performance, albeit the evidence remains weak (Derchi et al. Citation2021, Ikram et al. Citation2019, Ioannou et al. Citation2016, Maas Citation2018, Nigam et al. Citation2018, Russo and Harrison Citation2005). Nevertheless, archival evidence is unable to measure effort that people are willing to expend and it therefore remains unclear whether and to what extent incentives are able to influence managers’ effort when outcomes do not only have an impact on the firm itself, but also on the firm’s partners.

Moreover, the mere presence of incentives may signal strong room for improving performance and, as such, high partner risk (Campbell et al. Citation2007), leading investors to remain skeptical. Brown-Liburd and Zamora (Citation2015) suggest in this regard that investors may be skeptical of reported results when incentives are tied to these results, and show that investors only react positively when incentives are combined with assurance of the reporting. Further, Kolk and Perego (Citation2014) argue that it remains unclear whether ESG incentives are a credible sign of corporate awareness of social and environmental responsibility or another window dressing mechanism to keep executive compensation high. Consequently, it remains an empirical question whether firms’ partners perceive the provision of incentives to stimulate outcomes that may affect them, positively or negatively. In this study, we develop theory that the effect of incentives depends on the timing of feedback of the target outcomes.

2.3. Timing of feedback of target outcomes

Feedback about target outcomes plays a key role in our setting where not meeting targets may have severe implications, not only for the firm itself but also for the firm’s partners. Prior research shows that the extent of feedback about target outcomes can affect awareness and effort (Hörisch et al. Citation2019). However, it has not been examined how the timing of feedback affects effort. In reality, the timing of feedback about target outcomes can vary. Such outcome feedback may become visible over a short or longer time period. Also, firms may decide to measure their performance frequently versus less frequently or decide to frequently report about their outcomes or less frequently (Aboody and Kasznik Citation2000, Arnold et al. Citation2018). These variations can affect how fast managers can learn about the outcomes of their effort provision.

Overall, the extant accounting literature on feedback timing suggests that effort and performance decrease when it takes longer for feedback to become available.Footnote4 Specifically, Christ et al. (Citation2012) show that employee performance is lower when feedback comes later. The reason is that employees’ objectives become more salient when feedback is expected sooner. Similarly, Lambert and Agoglia (Citation2011) find that reviewees elicit lower effort levels when audit field work reviews become available after a longer time period. Further, some studies show that for learning tasks, future performance is lower when feedback is provided after a longer time period as learning costs increase (Lewis and Anderson Citation1985, Thornock Citation2016). At the same time, research provides evidence that increasing feedback frequency may actually be detrimental to performance as it may increase distraction and as people have a tendency to overweight recent information, which may hinder learning (Casas-Arce et al. Citation2021, Holderness et al. Citation2020).

However, how feedback timing affects managers’ effort in a setting in which not meeting targets may have serious consequences for their partners and how it influences collaborating partners’ willingness to expose themselves to this outcome risk has not been studied yet. On the one hand, one could expect that when outcomes become available after a short time period, the importance of those outcomes may become salient and firms will strive towards high performance. On the other hand, it is also possible that the same effort will be provided, regardless of feedback timing, as the outcomes will be made available to the partners at one point in the future anyway. In what follows, we formulate our expectations.

2.4. Effect of feedback timing on managers’ effort

To formulate our expectations about the effect of feedback timing on managers’ effort when incentives are absent, we rely on construal level theory. Construal level theory states that events expected to happen in the near future are mentally construed at a lower level than events expected to happen in the more distant future, which are mentally construed at a higher level (Liberman and Trope Citation1998, Sagristano et al. Citation2002). Specifically, mental representations of near future events are characterised by more concrete, peripheral and specific features, whereas distant future events are represented as more abstract, general and decontextualised (Trope and Liberman Citation2003, Maglio et al. Citation2013, Trope and Liberman Citation2010, Weisner Citation2015).

This means that when target outcomes become available over a short time period, individuals, when thinking about such outcomes, will construe these outcomes more clearly and concretely, considering the specific features of these outcomes. Moreover, one of those features is the effort provision needed to meet the target and it becomes clear that to achieve a good outcome in the short run, a reasonable amount of effort needs to be provided. In contrast, when the outcomes become available over a longer time period, the outcomes will be construed in a more abstract, general and decontextualised way and also the means needed to achieve the outcome will be less salient. This implies that the need to provide immediate effort is less salient when target outcomes materialise in the long run. As a result, less effort will be provided when outcomes materialise over a longer time period. Consequently, we formulate hypothesis 1 where we predict that managers will provide more effort when outcomes are expected to become available after a short versus after a longer time period:

H1: In the absence of incentives, managers will deliver higher effort when target outcomes become available after a short time period compared to a longer time period.

2.5. Effect of incentives on managers’ effort

Next, we raise the question of how effective incentives are that firms install to stimulate managers’ effort to meet targets that may affect their partners. We also examine how their impact differs when target outcomes become available after a short versus a longer time period. Overall, the extant literature remains unclear on how effective this type of incentives is. For ESG incentives, a specific example of this type of incentives, there is some scant evidence based on archival and survey studies that ESG incentives may lead to better performance (Derchi et al. Citation2021, Ikram et al. Citation2019, Ioannou et al. Citation2016, Maas Citation2018, Nigam et al. Citation2018, Russo and Harrison Citation2005). However, as archival evidence is unable to measure effort, it remains unclear whether and to what extent incentives are able to influence managers’ effort when outcomes do not only have an impact on the firm itself, but also on the firm’s partners. Hence, it is also possible that managers will not react to this type of incentives. As providing effort on these targets may be perceived as rather costly and uncertain to materialise, managers may not be swayed by an uncertain bonus. Moreover, they may also perceive these incentives as a signal from the firm towards stakeholders that these targets are also important, rather than as a way to stimulate their effort.

Furthermore, the question remains whether the impact of incentives differs when outcomes become available after a short versus after a longer time period. In this regard, it could be argued that when outcomes become available after a longer time period and incentives are tied to these outcomes, also the bonuses that may be received after meeting the targets will be discounted compared to when outcomes become available after a short time period. Thus, one could expect that the effect of incentives may especially arise when outcomes become available after a short time period, but not so much when they become available after a longer time period.

However, when construing the bonuses that may be received when meeting the targets, also the uncertainty of receiving the bonuses plays a role. In the presence of uncertainty, construal level theory posits that also feasibility and desirability considerations may play a role, and that when individuals make decisions regarding near future events, their decisions are more influenced by feasibility considerations than by desirability considerations whereas the opposite is true for decisions regarding distant future events (Liberman and Trope Citation1998, Sagristano et al. Citation2002, Trope and Liberman Citation2003, Trope and Liberman Citation2010). As such, when target outcomes become available after a short time period, feasibility concerns including the costliness, as well as the riskiness of the effort (i.e. of not receiving the bonus) become more salient and managers may be less likely to provide effort than when no incentives would be provided. In contrast, when outcomes are expected to become available after a longer time period, general and abstract features of the outcome may become more salient and desirability considerations will become more important than feasibility considerations according to construal level theory. Even though managers’ representation of the bonus, as a high-level construal, will be rather abstract, providing incentives will increase the desirability of a good outcome compared to when no incentives are provided. As such, managers’ effort provision could also be expected to increase compared to when there are no incentives when outcomes become available after a longer period.

Overall, given these conflicting and inconclusive arguments, we do not formulate any ex ante predictions, but we raise the following two research questions:

RQ1: How does the presence of incentives to meet targets that may affect the firm’s partners, relative to no incentives, influence managers’ effort provision?

RQ2: Is the effect of incentives compared to no incentives on managers’ effort provision different when target outcomes are expected to become available after a short versus longer time period?

2.6. Effect of feedback timing on partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk

When firms’ managers provide low effort, they can negatively affect their partners when targets are not met. The interactive nature allows us to examine how our variables of interest affect the willingness of firms’ partners to expose themselves to partner risk. This is interesting because the true effort of firms’ managers to meet targets that may affect their partners is unobservable to these partners. However, partners can still use information on the target outcomes as a proxy for the managers’ effort. Partners may learn about these outcomes through monitoring or the outcomes may be publicly reported such as in the firms’ annual or ESG reports (Ballou et al. Citation2006, Dhaliwal et al. Citation2011, Hahn and Kühnen Citation2013). If target outcomes are repeatedly bad, firms’ partners can attribute these outcomes to low effort provision. Consequently, they can protect themselves by decreasing the extent to which they expose themselves to this type of partner risk (i.e. number of offshored jobs) (Hajmohammad and Vachon Citation2016).

Clear information on firms’ performance is thus valuable for partners in collaborations (Vosselman and van der Meer-Kooistra Citation2009). However, when information that may affect the collaboration, such as information about target outcomes, comes relatively late, partners are less able to intervene and react quickly when things go downhill. Consequently, partners may perceive the situation as more risky because information needed to act is not as readily available when target outcomes become available after a longer time period instead of a shorter time period. Further, firms’ partners may anticipate that firms’ managers will be less motivated to provide effort when their outcomes become available over a longer time period. As such, in hypothesis 2 we predict that when incentives for the manager with whom partners collaborate are absent, partners will be less willing to expose themselves to the risk of the collaboration when outcomes become available over a longer period than when they become available over a short time period:

H2: In the absence of incentives for firms’ managers, partners will invest less in firms when target outcomes of the firms are expected to become available after a longer time period compared to a short time period.

2.7. Effect of incentives on partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk when outcomes become available after a short versus a longer time period

Next, we form expectations with regard to the impact of incentives implemented by firms to meet targets that may affect their partners on these partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk when outcomes become available after a short versus a longer time period. The presence of such incentives may be publicly disclosed in proxy statements (Robinson et al. Citation2011), annual reports (Veldman and Gaalman Citation2020), but also in ESG disclosures (e.g. Siemens Citation2020). Overall, it remains unclear how such incentives affect partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk. On the one hand, partners may want to bear more risk in the presence of incentives as investors may anticipate higher effort provided by the managers of the firms in which they invest. However, based on the extant literature, we argue that incentives will not lead to anticipation of higher effort, but actually have a detrimental effect on partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk. The reason is that partners may become skeptical of firms’ managers’ effort and performance when these managers receive incentives (Brown-Liburd and Zamora Citation2015). Specifically, incentives may signal that the firm is not doing well in this regard and can still improve its performance and reduce partner risk (e.g. Campbell et al. Citation2007, Russo and Harrison Citation2005). Also firms’ intentions behind the use of incentives that are meant to stimulate performance regarding targets that may affect partners may be less clear and not always be viewed as a strong signal of commitment to provide effort (Kolk and Perego Citation2014). As such, the presence of incentives may give firms’ partners the impression that the firms’ managers may not offer their best efforts to meet the targets. We thus expect that firms’ partners will make lower investments when incentives are present relative to when they are absent.

We expect this detrimental effect of incentives to be stronger when target outcomes become available over a short time period than when they become available over a longer time period. The reason is that, as mentioned above, we predict that firms’ partners will invest relatively little in the firms anyway when outcomes become available over a longer time period. As such, we expect the impact of incentives on partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk to be relatively small when outcomes become available over a longer time period. Based on these arguments, we formulate our third and fourth hypothesis:

H3: The presence of incentives will have a negative effect on partners’ levels of investment in the firm compared to when no incentives are provided.

H4: The negative effect of incentives on partners’ levels of investment will be stronger when outcomes become available over a short time period than when they become available over a longer time period.

3. Method

3.1. Experimental setting and participants

We use an investment game with a 2 × 2 between-subjects design with 12 periods of repeated decisions in an ESG setting. This setting speaks to our research setting as not meeting ESG targets may have detrimental effects for firms’ partners. We use the experimental z-Tree software to programme the experiment (Fischbacher Citation2007). We create an interactive research setting by adapting the multi-period investment game used in prior studies (Basu et al. Citation2009, Berg et al. Citation1995, King-Casas et al. Citation2005, Lunawat et al. Citation2021). In our investment game, a participant in the role of firm manager (i.e. the manager) and another in the role of the firm’s partner (i.e. the investor) interact repeatedly. The investor chooses whether and how much to invest in the firm represented by the manager. The firm manager chooses how much effort to provide to reduce the risk of exceeding an emission norm.Footnote5 Similar to many settings in practice, the investor bears severe consequences when targets are not met. Specifically, the investor loses his or her return when the manager does not stay below the emission norm. The outcome of providing effort is uncertain. If the manager provides more effort, the risk of exceeding the norm decreases. The investor, who never learns the effort of the manager, can still learn about the outcomes and react on these outcomes by adjusting investments in future periods.

176 business students participated in our experiment.Footnote6 Each participant was randomly assigned to a manager-investor dyad (n = 88 dyads). Managers and investors remained paired with each other during the experiment. Managers and investors in the experiment receive points based on their performance. We use an exchange rate of one point equalling 0.025 euro to determine the participants’ compensation. On average, managers earned 37.180 points per period (i.e. a total average compensation of 11.15 euros). Investors earned on average 34.348 points per period (i.e. 10.30 euros in total). The average age of participants is eighteen years and nine months and they have six months of part-time working experience. Females comprise 35.8% of the participants. On Likert scales from one to seven, participants indicate that they attach importance to the climate challenge (mean = 5.625), that they take action to reduce pollution (mean = 4.670), and that they attach importance to reducing greenhouse gasses (mean = 5.665). These means are significantly different from the midpoint four. ANOVAs of feedback timing and incentives on these variables demonstrate that the randomisation of participants was generally successful.

3.2. Experimental procedures and manipulations

Participants received instructions on their computer screen. During the experiment, they could also refer to a hand-out that explained how their compensation was calculated. At the start of the experiment, participants learned their role and the role of their counterpart. Participants were also told in the instructions that the experiment would last between 10 and 15 periods. We made this design choice to avoid end-game effects (Young et al. Citation1993). In reality, participants had to make decisions over 12 periods.

All participants (investor and manager roles) learned that the activities in the manager’s firm produced greenhouse gasses. To stay below the prevailing emission norm, the manager could deliver effort. In our experiment, the emission norm was the same for every period and in all conditions. Further, in each period, managers in all conditions had to decide about whether and how much effort to provide to stay below this emission norm. As shown in Appendix A, effort levels were expressed on a scale of zero to 15, and higher effort levels represented higher costs for the manager (Cardinaels et al. Citation2018, Choi Citation2014, Hannan Citation2005, Kuang and Moser Citation2009). The cost related to effort is a quadratic function of the effort levels (cost = effort2/15) and was deducted from the compensation of the manager. The range of corresponding costs varied from zero to 15. Each effort level also corresponded to a given probability that the firm would stay below the emission norm. A minimum effort would result into an 80% chance of exceeding the norm, whereas spending maximum effort would result only in a 5% chance of exceeding the norm, representing a 95% chance that the firm would stay below the norm.

Both investors and managers further learned that the investor could invest between zero and 30 points in the manager’s firm in each period. Following prior studies, investments were subsequently quadrupled because they generate value for both the investor and the manager (Basu et al. Citation2009, Berg et al. Citation1995, Lunawat et al. Citation2021). Managers received half of this quadrupled amount, but investors only received the other half if the firm stayed below the emission norm. This means that when the firm stayed below the emission norm, the investor’s payoff equalled 30 points plus the amount of their initial investment. However, when the firm did not stay below the emission norm, the investor’s share of the quadrupled investment was entirely devaluated, in which case the payoff equalled 30 points minus the initial investment.Footnote7 Importantly, when deciding on the effort level, the manager did not know the investment of the investor, nor did the investor know how much effort the manager expended when making the investment.Footnote8 Appendix B graphically presents the sequence of events in the experiment.

The experiment has a 2 × 2 design in which we manipulate feedback timing and whether or not managers receive incentives for staying below the emission norm.

Feedback timing: We manipulate feedback timing as the amount of time that participants knew it would take, after making their effort or investment decision, for outcomes to become available to them.Footnote9 Both managers and investors received feedback about the outcome at the same time.Footnote10 In the short time period condition, outcomes become available one time period after the time period in which the decision with regard to the outcome was made; in other words, the outcome for the manager’s effort choice in period one was reported to both parties at the start of period two. In the long time period condition, outcomes become available after three experimental periods; in other words, the outcome of the manager’s effort choice in period one was thus reported to both parties at the start of period four and the outcome of period two at the start of period five, etc. While participants did not make any decisions anymore after the 12th period, extra feedback periods followed given the time delay in feedback. In the short time period condition, participants learned in the 13th period whether the firm stayed below the emission norm for which the manager provided effort in the 12th period. In the long time period condition, there was a 13th, 14th, and 15th feedback period in which participants learned about the outcome for the emission norm for which effort was provided in, respectively, the 10th, 11th, and 12th period. Similarly, participants in the short (long) time period learn about the profit they made in the previous period (three periods ago). Based on this output, managers were able to calculate how much the investor had invested in the previous period (three periods ago). During the experiment, participants could always refer to a handout that explained how their profit was calculated.

Incentives: We also manipulate whether or not the manager is rewarded for positive performance with regard to the emission norm. In the no incentives condition, the manager receives a flat wage of ten points regardless of whether or not he or she stays below the emission norm. In the incentives condition, the manager receives a bonus of 20 points for each period in which he or she stays below the emission norm. For periods in which his or her firm does not stay below the emission level, the manager does not earn a bonus. The presence of this incentive is, similarly to reality, known to all parties.Footnote11

After reading the instructions, participants performed a test checking their understanding of the instructions. When a test item was answered incorrectly, a pop-up screen appeared with feedback. Participants had to answer all items correctly before proceeding to the experimental tasks. At the end of the investment task, participants received a post-experimental questionnaire. It contained manipulation checks and further collected information about decisions made by participants during the experiment, demographics, and participant’s personality characteristics.Footnote12

4. Results

4.1. Manipulation checks and descriptive statistics

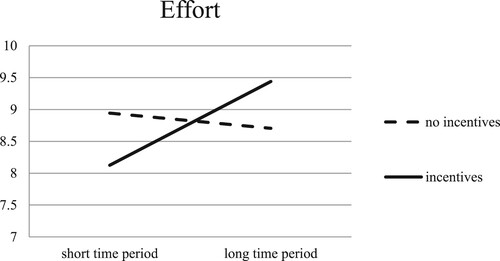

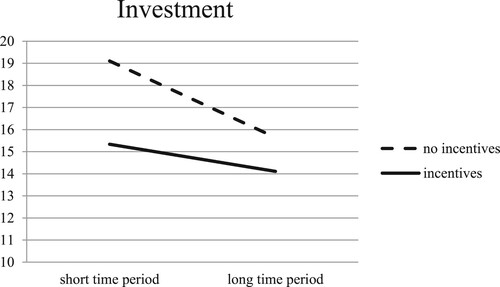

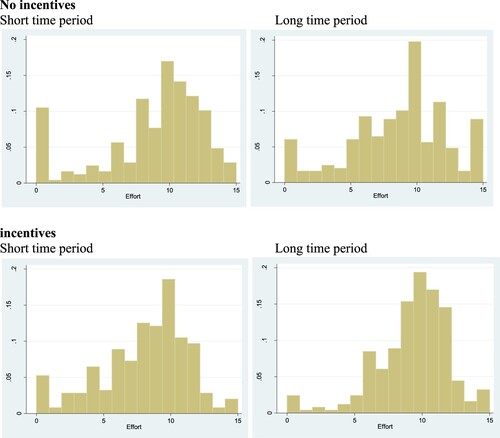

Manipulation check items in our post-experimental questionnaire confirmed that our participants had a very thorough understanding of our investment game.Footnote13 We include all participants in our analyses, as removing participants who failed manipulation checks does not change our inferences. offers an overview of the descriptive statistics for the variables we use in our analyses. In the absence of incentives, the average effort level provided by managers in the short time period condition equals 8.943, while the average effort level in the long time period condition equals 8.705. In the presence of incentives, managers expend on average an effort level of 8.125 in the short time period condition, and an effort level of 9.439 in the long time period condition.Footnote14 Further, in the absence of incentives, investors’ investments on average equal 19.106 points in the short time period condition and 15.644 points in the long time period condition. When incentives are present, investments are 15.337 points on average in the short time period condition and an average of 14.110 points in the long time period condition. graphically presents the means of effort and presents the means of investment over the four conditions. In what follows, we present the analyses to test our hypotheses.

Figure 1. Effect of incentivesa and feedback timingb on effortc. aIncentives is manipulated as a between-subjects factor at two levels: no incentives and incentives. In the no incentives condition, the manager does not receive incentives for staying below the emission norm. In the incentives condition, the manager receives a 20-point bonus for staying below the emission norm in a given period, and no bonus otherwise. bFeedback timing is manipulated as a between-subjects factor at two levels: short time period and long time period. In the short time period condition, the emission level outcome realises within one period. In the long time period condition, the emission level outcome realises over three periods. cEffort is expressed on a scale from 0 to 15. Each level on this scale corresponds to a cost borne by the manager and to a probability that the manager will stay below the emission norm.

Figure 2. Effect of incentivesa and feedback timingb on investmentc. aIncentives is manipulated as a between-subjects factor at two levels: no incentives and incentives. In the no incentives condition, the manager does not receive incentives for staying below the emission norm. In the incentives condition, the manager receives a 20-point bonus for staying below the emission norm in a given period, and no bonus otherwise. bFeedback timing is manipulated as a between-subjects factor at two levels: short time period and long time period. In the short time period condition, the emission level outcome with regard to the effort level in a given period realises within one period. In the long time period condition, the emission level outcome realises over three periods. cInvestment is the number of points that the investor wants to invest in the manager’s firm. The minimum amount investors can invest is 0, and the maximum amount is 30.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

4.2. Results of hypothesis tests

4.2.1. Effect of feedback timing and incentives on managers’ effort (H1 & RQ1-2)

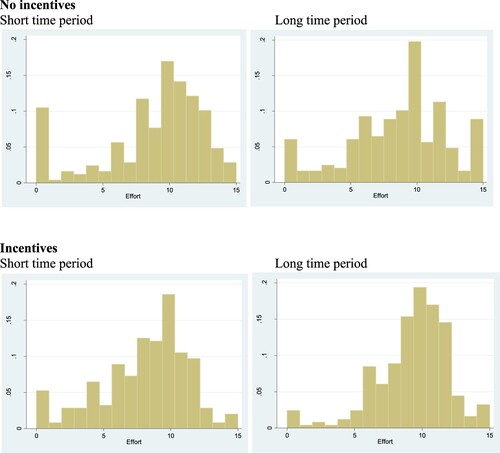

In our first hypothesis, we predict that when incentives are absent, managers’ effort will be lower when target outcomes become available over a longer time period than over a short time period. Further, we raise the research questions of how incentives influence managers’ effort provision and whether the effect of incentives is different when outcomes become available after a short versus longer time period. We measure effort as the effort level chosen by the manager with zero as the lowest possible effort level and 15 as the highest possible. Due to the non-normal distribution of effort (), we test our hypothesis and answer our research questions using ordered logistic regressions (De Vaus Citation2013, Haesebrouck et al. Citation2021, Kennedy Citation2008), where we categorise the effort levels into four categories, such that the distribution of observations over categories is as equal as possible.Footnote15,Footnote16 This categorised effort variable is used as the dependent variable in our analyses. The independent variables used in the regressions are the dummy variables ‘feedback timing’ and ‘incentives’. Feedback timing equals zero for the short time period condition and one for the long time period condition. Incentives takes the value of zero for the no incentives condition, and the value of one for the incentives condition where incentives for staying below the emission norm are present.

Figure 3. Histogram of efforta. aEffort is expressed on a scale from 0 to 15. Each level on this scale corresponds to a cost borne by the manager and to a probability that the manager will stay below the emission norm.

provides the results of our analyses. Because observations of individual subjects over different periods are not independent, we always cluster on subject (i.e. dyad) level. To test our first hypothesis, we examine the effect of the feedback timing variable on effort provided by managers within the no incentives condition (, Panel A, Model 1). However, we do not find a significant effect of feedback timing (β = −0.262, p = 0.241; one-tailed).Footnote17,Footnote18 We thus do not find support for our first hypothesis, predicting that when incentives are absent, effort is higher when outcomes become available over a short than over a long time period. It may imply that the predicted negative effects of longer feedback timing might be less likely to arise in a setting where firms’ partners can anticipate and react to outcomes.

Table 2. Ordered logistic regressions of incentivesTable Footnotea and feedback timingb on effortc.

To explore the effect of incentives on effort (RQ1), we test the main effect of incentives (, Panel C, Model 1). We, however, find no significant main effect (β = −0.159, p = 0.536). Results remain similar when including the control variables specified in footnote 18 (Model 2: β = −0.137, p = 0.601). We also explore the effect of incentives on effort in the short and long time period conditions separately (, Panels D and E, Model 1). Interestingly, we find a significantly negative effect of incentives (relative to no incentives) in the short time period condition (β = −0.595, p = 0.087), but no evidence of an effect in the long time period condition (β = 0.275, p = 0.468). Next, to analyse whether there is a difference in the effect of incentives on effort among the short and long time period condition (RQ2), we run an ordered logistic regression of incentives, feedback timing and their interaction on effort (, Panel F, Model 1). We find a significant interaction effect (β = 0.869, p = 0.092), meaning that the effect of incentives indeed depends on the feedback timing condition.Footnote19,Footnote20,Footnote21 Overall, when outcomes become available after a short time period, incentives lead to lower effort. Such a reduction in effort as a result of incentives is not observed when outcomes become available over a longer time period. As an additional analysis, we examine the simple effects of feedback timing in the presence of incentives (, Panel B, Model 1) and we find significantly lower effort levels when outcomes become available after a short time period compared to after a longer time period (β = 0.637, p = 0.072). Hence, when outcomes become available after a short time period, incentives do not only lead to significantly lower effort levels than when there are no incentives, but effort levels in the short time period – incentives condition are also significantly lower than in the long time period – incentives condition. This indicates that incentives are detrimental to effort when managers’ focus is on the short run.

Further, in the PEQ, we have a process measure that captures on a seven-point Likert scale how managers construe outcomes that are expected to become available in the near future compared to the distant future (‘When I made decisions, I had a clear idea of the outcome that I expected for that round’). We run a regression within the no incentives condition with this variable as dependent variable and feedback timing as independent variable. Even though our hypothesis test did not provide evidence for our first hypothesis, we see, consistent with our theoretical arguments for this hypothesis, that when incentives are absent, managers had indeed a less clear idea of the outcomes they expected for their decisions in that round when outcomes become available over a longer than over a short time period (β = −1.409, p = 0.002; untabulated).

Untabulated results of the regression analysis within the short time period condition of incentives on this PEQ variable measuring the extent to which participants had a clear idea of the outcome that they expected for that round show that, in the short time period condition, managers construed these outcomes less clearly when they received incentives versus when they received no incentives (β = −1.182, p = 0.012). This suggests that incentives, relative to no incentives, make managers focus more on the uncertainty of the outcomes and getting the bonus when those become available over a short time period. When regressing incentives, feedback timing and their interaction on this PEQ variable, we also find a significantly positive interaction effect between feedback timing and incentives on managers’ assessment of how clear their idea was of the outcomes they expected (β = 1.500, p = 0.028). However, within the long time period condition, we find no significant difference when there are no incentives versus when there are incentives (β = 0.312, p = 0.521). Interestingly, however, managers’ assessment of the statement ‘I attached much importance to feedback about the emission norm’ is significantly higher in the long time period condition when managers receive incentives compared to when there are no incentives (β = 0.727, p = 0.061), which is consistent with the idea of incentives increasing managers’ focus to the desirability of the outcome in the long time period condition.

4.2.2. Effect of feedback timing on partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk when incentives are absent versus present (H2, H3, & H4)

We measure partners’ willingness to expose themselves to risk as the amount that investors were willing to invest in the manager’s firm, with a minimum of zero and a maximum of 30 points (). Similarly to our effort variable, we categorised investment into four categories, such that the distribution of observations over categories is as equal as possible.Footnote22 The resulting variable investment is used as a dependent variable in our ordered logistic regressions ().Footnote23 In our second hypothesis, we predict that when incentives are absent for the managers of the firms, partners will invest less in firms when outcomes of the firms are expected to become available after a longer compared to a short time period. Our third hypothesis predicts that the presence of incentives will have a negative effect on partners’ investments in the firms compared to no incentives and in our fourth hypothesis, we expect that this negative effect will be stronger when outcomes become available over a short than over a longer time period.

Figure 4. Histogram of investmenta.aInvestment is the number of points that the investor invests in the manager’s firm. The minimum amount investors can invest is 0, and the maximum amount is 30.

Table 3. Ordered logistic regressions of incentivesTable Footnotea and feedback timingb on investmentc

To test our second hypothesis, we examine the simple effect of feedback timing on investment within the no incentives conditions (, Panel A, Model 1) and we find a significantly negative effect (β = −0.683, p = 0.050; one-tailed).Footnote24 Our third hypothesis predicts a negative main effect of incentives. We use an ordered logistic regression of incentives on investment (, Panel C, Model 1) and find a significantly negative effect (β = −0.515, p = 0.028; one-tailed). To further explore the effect of incentives, we run this regression separately within the short time period (, Panel D, Model 1) and the long time period condition (, Panel E, Model 1). Within the short time period condition, we find a significantly negative effect of incentives (β = −0.734, p = 0.066), but not within the long time period condition (β = −0.295, p = 0.422).Footnote25 The reason that we do not find a significant effect of incentives within the long time period condition is likely that investments in that condition are already relatively low when incentives are absent. In hypothesis four, we predict an ordinal interaction effect between incentives and feedback timing on investment, with the effect of incentives being smaller in the long time period condition than in the short time period condition. Even though the simple effects tests showed a significantly negative effect of incentives in the short time period condition but no significant effect in the long time period condition, we do not find a significant interaction effect (, Panel F, Model 1: β = 0.497, p = 0.179; one-tailed).Footnote26,Footnote27,Footnote28 Further, additional analyses show also no simple effect of feedback timing on investment within the incentives condition (, Panel B, Model 1: β = −0.196, p = 0.575).

Overall, these results offer weak evidence for H2, i.e. that firms’ partners such as investors, in the absence of incentives, are less willing to expose themselves to risk when outcomes are set to become available after a longer time period compared to a short time period. Further, we provide some evidence, consistent with H3, that incentives have a negative effect on partners’ willingness to expose themselves to risk. However, we only find this effect when outcomes become available after a short time period. We find no evidence that incentives have an effect when outcomes become available after a long time period. We also do not find statistical evidence that the effect is smaller in the long time period condition than in the short time period condition (H4). In general, we conclude that firms’ partners invest most when outcomes become available after a relatively short time period and firms’ managers receive no incentives.

In our PEQ, we asked participants in the role of investors to assess some statements on seven-point Likert scales and we use their assessments as process measures. Specifically, investors’ assessments of the statement ‘Feedback on whether the company stayed below the emission norm came fast enough’ provides corroborating evidence for our second hypothesis, as investors agreed significantly less with this statement in the long time period condition compared to the short time period condition when incentives were absent (β = −1.455, p < 0.001; untabulated). Investors also agreed less with the statement ‘The amount that I invested influenced the effort that a manager subsequently provided’ in the long time period condition than in the short time period condition (β = −0.568, p = 0.058; untabulated), which indicates that they felt less in control when outcomes became available in the long time period. Investors also indicated to a higher extent that they found that ‘the manager had to provide much effort if I invested much’ (β = 0.773, p = 0.049; untabulated) in the long time period condition than in the short time period condition when incentives were absent, indicating that investors were more skeptic about effort provision of managers in the long time period condition.

Other items of the PEQ offer support for our theoretical arguments for H3. We argued that when firms’ managers receive incentives, investors would be less likely to invest because incentives would make it more salient that the firm is not sustainable enough. This may make investors more skeptical about whether or not they should invest. Consistent with this reasoning, investors are less likely to indicate that they had enough information to decide how much they would invest in the incentives condition compared to the no incentives condition (β = −0.750, p = 0.057; untabulated). Further, investors’ skepticism about the managers’ effort is apparent from their assessment of the item ‘Providing effort was important for the manager’s reputation’, which is significantly lower in the incentives condition than in the no incentives condition (β = −0.614, p = 0.049; untabulated). It suggests that it was more difficult for managers to build a good reputation by delivering high effort when he or she also received incentives to do so.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we examine whether and how incentives and the timing of feedback about target outcomes affect firms’ managers’ effort and their partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk. Overall, our results suggest that when feedback is made available over a short time period, it is better not to provide incentives as incentives lead to lower managerial effort levels and a lower willingness of partners to invest in the partnership. Moreover, our results indicate that increased transparency by making feedback available over a short time period while not providing incentives is also preferable over providing feedback over a longer time period (regardless of incentives). While effort levels do not significantly differ among these three conditions, partners invest much more in the no incentives – short time period condition.

With this paper, we contribute to the literature on incentives to meet targets that not only have implications for the firm itself, but also for their partners. By doing so, we contribute to the extant accounting literature on the increasingly popular practice of providing ESG incentives as a specific type of such incentives (Brown-Liburd and Zamora Citation2015, Campbell et al. Citation2007, Kolk and Perego Citation2014, Russo and Harrison Citation2005). Specifically, we show that, rather than stimulating effort, incentives may have unintended consequences, especially when outcomes become available over a short time period. Moreover, under those circumstances, incentives negatively affect the willingness of firms’ partners to invest in the partnership. Hence, our results make firms considering to implement such incentives, including ESG incentives, aware of their potential negative consequences. Further, we contribute to the literature on feedback timing (Christ et al. Citation2012, Lambert and Agoglia Citation2011, Thornock Citation2016) by using a setting in which not complying with certain requirements may severely affect the firm’s partners. Negative outcomes may, for example, affect partners’ reputation, financial exposure and their compliance with laws (Giannakis and Papadopoulos Citation2016).

We also provide practical insights. Overall, when firms, whose partners may be subject to partner risk, have a choice between providing feedback over a short versus a longer time period and between providing incentives versus no incentives, our results suggests it is optimal for these firms and their partners to provide feedback over a short time period without incentives. Specifically, we find that when feedback is provided over a short time period, incentives are detrimental compared to no incentives for both managerial effort and partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk. Our results also show that providing feedback over a short time period without incentives leads to a higher willingness by partners to expose themselves to partner risk than providing feedback over a longer time period (with our without incentives).

Regarding managerial effort, we do not find significant differences between providing feedback over a short time period without incentives and providing feedback over a longer time period (with or without incentives). However, because intentionally delaying feedback when it would be possible to provide feedback earlier would reduce transparency, we argue that it is still better for firms to provide feedback over a short time period. Consequently, given these high levels of managerial effort when feedback is provided over a short time period without incentives, their partners, who are most likely to expose themselves to partner risk under these conditions, will also be subject to lower levels of partner risk. When feedback, due to circumstances, has to be provided over a longer time period, our results do not show significant differences between incentives and no incentives on managers’ effort and partners’ willingness to expose themselves to partner risk.

This study is subject to some limitations, raising opportunities for further research. While we manipulate feedback timing as short versus relatively long, feedback provision still happens over a relatively short window. This was the most appropriate manipulation, given our method, and was also consistent with the extant literature (e.g. Lambert and Agoglia Citation2011). Archival data can validate if our results extend to very long windows, where the impact of target outcomes might materialise after years. Further, in our experiment, both managers and investors received feedback about the outcome at the same time. In reality, it is possible and likely that managers receive the information before other parties and that they wait some time with publicly disclosing the information. However, to avoid unnecessary complexity in the experimental design, we decided to keep the time periods the same for managers and investors. Future research can examine this element more deeply by studying how differences in timing for different parties may affect our results, and how managers use their discretion with regard to the timing of feedback. In reality, firms may also have more time to work on certain targets than on others. It may be interesting for future research to examine the impact on effort of such differences.

Another limitation is that we did not tie a cost to the use of incentives. When managers receive incentives such as bonuses as part of their compensation, this often represents a cost. If a real cost for the firm was tied to the incentives, investors might have been even less likely to invest in the firm in the presence of incentives. To keep the experimental design simple, we further also did not impose a negative outcome for the firm itself or a penalty for the manager for not staying below the emission norm. We expect that the results might have been stronger under those circumstances. For example, the importance of providing effort might be more pressing when there would be a costly, negative outcome for the firm, which would especially be experienced in the short time period condition. Such a negative outcome might be less pressing in the long time period condition, given the higher level construal of the outcome in the latter condition. And introducing a personal penalty for the manager would function directionally similar, but potentially even stronger than incentives, given that people are loss averse (Hannan et al. Citation2005). Also regarding the effect on investment levels, we would expect directionally similar results. Accounting for a negative outcome for the firm might increase trust that the manager would provide effort. In general, it would be interesting for future research to examine alternative forms of incentives such as penalties instead of bonus contracts.

Another design choice is that it is the manager (not the firm) who benefits directly from the investments and meeting the target. However, when the firm would also benefit we expect our results still to materialise as we would assume the interests of the manager and firm to be aligned in this partnership setting. Hence, by letting the manager benefit directly from the extent to which partners are exposing themselves in the experimental game, we are constructing a representative setting. Further, the experiment does not account for any explicit indirect effects for the firm, such as implications for the firm’s reputation. However, given that it is a multi-period game, we allow for reputational repercussions for the manager who represents the firm. Overall, our experimental design, consistent with the original investment games it was based on (e.g. Basu et al. Citation2009, Berg et al. Citation1995, Lunawat et al. Citation2021), does not introduce all complexities as one would observe in actual partnership settings. Nevertheless, our design is relevant for many partnership risk we see in practice. Future research can study some of these additional features as we mentioned above, and see if our results are robust to adding additional complexities.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (885.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We appreciate the helpful comments from Mark Clatworthy (editor) and two anonymous reviewers. We further want to thank Brian Ballou, Lieven Brebels, Alexander Brüggen, Qing Burke, Jeff Clark, Jason Kuang, Victor van Pelt, Bill Rankin, Naomi Soderstrom, and workshop participants at the 2018 MAS Meeting, the 2018 EAA Annual Conference, the 2018 GMARS Conference, the 2018 AAA Annual Conference, at KU Leuven, and at Miami University for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2023.2241135.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This implies that collaborating partners, who may bear severe consequences of negative outcomes, can take actions in response to bad performance. For example, partners may reduce this risk by lowering the number of offshored jobs when outcomes repeatedly turn out to be negative (Hajmohammad and Vachon Citation2016). Managers of firms to which activities are offshored, in turn, may anticipate reactions of the former when deciding how much effort to provide when pursuing targets. This interactive setting makes our study unique.

2 Incentives to stimulate effort with regard to targets that may also affect third parties may be perceived differently than traditional incentives implemented to stimulate performance with regard to the firm’s core responsibilities, where the link between incentives and firm results may be clearer. For example, the former type of incentives may be perceived more as a signal than as an actual attempt to stimulate effort.

3 The presence of such incentives is often public knowledge as information about managerial compensation is often discussed in annual reports or proxy statements (Robinson et al. Citation2011, Veldman and Gaalman Citation2020).

4 A different, but related, stream of literature focuses on the time horizon of targets and makes similar predictions. Specifically, goal setting research argues that targets with a short time horizon motivate more goal-directed behavior than targets with a longer time horizon (e.g., Anand Citation2017, Bandura and Schunk Citation1981, Bandura and Simon Citation1977, Heath et al. Citation1999, Locke and Latham Citation1990). However, in this paper, we are interested in the impact of feedback timing, i.e., whether the outcomes of a task or decision become available after a short or longer time period, and we leave the question about time horizon of targets to future research.

5 As our business student participants may have a better understanding of investor relationships than other types of partnerships, we describe our research setting as an investment game. Consistent with previous studies that used this game to study economic exchange between two parties (e.g., Basu et al. Citation2009, King-Casas et al. Citation2005), our experiment also uses the terminology of ‘investment game’, ‘investment’, and ‘investor’ when describing the partnership setting. Nevertheless, our setting represents a variety of situations where firms’ partners can be severely affected when firms with whom they contract do not meet certain targets. This type of partnerships includes offshoring relationships, subcontracting, buyer-supplier relationships, and investor relationships. Since all important characteristics of our research setting (e.g., partner risk, expending effort) are present in our setting, our game is appropriate to represent our research setting and can speak to a broad range of partnerships observed in practice.

6 This experimental study is part of a research project funded by our host institution (project number OT/13/016). The host institution reviewed a detailed description of the method as part of the research proposal.

7 In reality, it is possible that also the firm of the manager will bear a cost when it misses these type of targets. However, we are mainly interested in how feedback timing and incentives affect managers’ decisions to provide effort to meet the targets and partners’ decisions to invest in the firm in settings where not meeting these targets has negative consequences for the partners. To not make the experiment more complicated, we decided not to add a cost for the firm of not staying below its emission norms in any of the conditions.

8 Managers and investors make their decisions simultaneously like in many real partnerships (see Appendix B). When experiments are more interested in reciprocal behavior, the second player can learn about the investment made by the first player before making his or her own choice (e.g., Basu et al. Citation2009, Berg et al. Citation1995, Coricelli et al. Citation2006, Lunawat et al. Citation2021). We refrain from this latter choice as we are interested in how the impact of feedback timing and incentives affect managers’ decisions to provide effort, rather than studying reciprocity.

9 While the difference between feedback provided in the short and long time period condition is only a few minutes, our manipulation of this variable is similar to other studies who also delay feedback only for one period versus more than one period (Lambert and Agoglia Citation2011).

10 In reality, it is possible and likely that managers receive the information before others. However, we expect people to react based on the amount of time after which the information becomes available to themselves. For example, if the information becomes available for the manager in the short run and for investors after a longer time period, we expect managers to react as in our short time period condition, and investors as in our long time period condition.

11 By providing a flat wage of ten points in the no incentives condition and a bonus of twenty points in the incentives condition, we made the expected payoffs for managers over the conditions as equal as possible. Given the probabilities related to the different levels of effort, the average of the expected values of the bonus in this condition (i.e., not considering the cost of effort and the investor’s investment), corresponding to each of the different levels of effort, still equals 11.5 points, which is slightly higher than the fixed wage condition. Nevertheless, it is comparable to operationalizations in prior research (e.g., Tafkov Citation2013). Further, actual pay levels for managers in the no incentives (mean = 11.54 euros) and the incentives condition (mean = 10.76 euros) are also not significantly different (t(86) = 1.004, p = 0.318).

12 The complete research instrument is included in the supplemental data.

13 All participants correctly assessed whether they were assigned to the role of manager or investor. 98.86 percent knew that investors were never informed of the levels of effort delivered by the managers. The statement ‘When a decision is made in a given period, you are immediately informed at the start of the next period whether the manager has stayed below the emission norm’ was true (false) in the short (long) time period condition. All participants gave the correct answer, except for one investor in the no incentives–short time period condition. Also, all of the managers and 97.73 percent of the investors knew that there was always a small chance that the manager would not stay below the emission norm even if the manager delivered the maximum effort. The statement ‘staying below the emission norm has an influence on the reward of the manager,’ was answered correctly by 93.18 percent of the managers and 93.18 percent of the investors. Remarkably, except for one, all participants who failed this manipulation check were assigned to the no incentives condition. It might be logical that people in this condition might still fear that their reward will be lower, given that investors may invest less in future periods when outcomes turn out to be bad.

14 Descriptive statistics further show that no managers provide an average effort level (i.e., the average of the twelve periods in which effort was expended) lower than 4.42, which indicates that all managers provided at least some effort during most periods. Overall, we do not find evidence of managers deciding not to provide any effort at all.

15 presents histograms of the chosen effort levels for each of the four experimental conditions. As is typical in investment games, effort is not normally distributed because of an additional peak around zero effort. Moreover, skewness and kurtosis tests show that when we use effort as an independent variable in an OLS regression, the standard errors are not normally distributed.

16 The first category consists of effort levels zero to six; the second, effort levels seven to nine; the third, levels 10 and 11; and the fourth, 12 to 15. Analyses with other categorizations using four categories and categorizations using three or five categories give similar results. By categorizing our observations, outliers are automatically truncated.

17 All reported p-values in this paper and in the tables are two-tailed, except for hypothesis tests which are one-tailed, as hypotheses make directional predictions.

18 As robustness tests, we repeat our analyses including several control variables (, Model 2). The control variable feedback investment captures how much the investor invested in the previous period in the short time period condition or three periods prior to the current period in the long time period condition. Next, long-term personality is a personality measure based on the Delaying Gratification Inventory by Hoerger et al. (Citation2011) to measure how well managers cope with delayed gratification. We also include social value orientation (SVO), coded as one for prosocial managers and zero otherwise, consistent with the instrument of Van Lange et al. (Citation1997). The remainder are classified as proselfs (individualistic and competitive managers). This category also includes a few managers (n = 7) that cannot be classified as either prosocial or proself. The variable climate orientation is the managers’ assessment of the statement, ‘I attach importance to the climate challenge’ on a Likert scale from one to seven. Including these control variables in our model does not significantly alter results for hypothesis one (β = −0.109, p = 0.393; one-tailed).

19 Results are robust to including the control variables specified in footnote 18 (effect of incentives on effort within the short time period condition: β = −0.602, p = 0.070; effect of incentives on effort within the long time period condition: β = 0.431, p = 0.311; interaction effect of incentives and feedback timing on effort: β = 0.954, p = 0.069; , Panels D, E, and F, Model 2). Leaving out the observations for period one (in the short time period condition) and observations for periods one, two and three (in the long time period condition) gives similar results for these analyses. The results also remain similar for the three models when adding period fixed effects. For this reason, results in general do not seem to be influenced by potential reputation effects.

20 Moreover, as expected, feedback investment has a positive effect on effort (β = 0.035, p = 0.005) when including it together with the other control variables in the latter regression (, Panel F, Model 2). This indicates that managers to a certain extent reciprocate high investments. To rule out reciprocity as an alternative mechanism for our findings, we ran an ordered logistic regression with the three-way interaction between incentives, feedback timing, and feedback investment on managers’ effort levels. However, there is no significant effect of the interaction between incentives and feedback investment (β = −0.019, p = 0.499), nor of the interaction between feedback timing and feedback investment (β = 0.029, p = 0.498), nor of the three-way interaction between incentives, feedback timing, and feedback investment (β = 0.0003, p = 0.995). We conclude that the extent of reciprocity does not depend on the experimental conditions. Next, we examine if there is a learning period to reciprocity by dividing the twelve experimental periods into four categories, with three periods each. We repeat our regression analyses per category and we find significantly positive effects of this variable in each of the four regressions (time category 1: β = 0.048, p = 0.095; time category 2: β = 0.031, p = 0.074; time category 3: β = 0.035, p = 0.046; time category 4: β = 0.045, p = 0.004), indicating that there is no learning period because managers already reciprocate in the first periods.