Abstract

In this paper, we review and critique the use of institutional theory in social and environmental accounting (SEA) research and discuss whether this has helped or hindered in furthering a critical research programme that is concerned with questions of power and emancipation. This research focus is warranted by broader debates within institutional theory as well as the SEA literature. Insofar as institutional theory is concerned, there are disagreements as to whether this theory can be imbued with critical intent or whether it is trapped in a normal science tradition of constantly extending and refining theory that detracts from such intent. By contrast, within the SEA literature, we find a largely inverse criticism suggesting that its lack of theoretical sophistication has diminished its critical potential. We show that most institutional research on SEA under review has not advanced research in a critical direction. However, this has little to do with the normal science ideal underpinning institutional theory but is rather due to the failure to keep up with key conceptual developments crystallising its critical potential. We outline a research agenda that may turn institutional research on SEA into a more critical research programme while simultaneously developing institutional theory conceptually.

1. Introduction

Social and environmental accounting (SEA) research has evolved into a substantial field of scholarship that is broadly divided between positivist approaches that emphasise the managerial usefulness of accounting information and capital markets interests and inter-disciplinary approaches that often seek to advance critical insights into the wider, societal roles that accounting can play as a vehicle for enhanced equity and sustainability (Gray Citation2002, Gray et al. Citation2010, Unerman and Chapman Citation2014, Andrew and Baker Citation2020, Baker et al. Citation2023).Footnote1 Within the latter strand of research, a vibrant debate about the roles of theories and theorising has emerged alongside an expanding range of theoretical perspectives for making sense of SEA practices (Parker Citation2005, Adams and Larrinaga-González Citation2007, Citation2019, Chen and Roberts Citation2010, Spence et al. Citation2010, O’Dwyer and Unerman Citation2016, O’Dwyer Citation2021). While inter-disciplinary research on SEA was long dominated by a small number of social theories, such as legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and political economy theory, it has evolved into an increasingly diverse field of scholarship. One of the most recent and rapidly growing streams of research is that informed by institutional theory. While arguments inspired by institutional theory have always had an implicit influence on parts of the SEA literature, especially that drawing on legitimacy theory (Deegan Citation2002, Larrinaga-González Citation2007), they have increasingly come into their own and started to underpin a relatively self-contained body of research. Leading SEA scholars, such as Adams and Larrinaga-González (Citation2007) and Deegan (Citation2006, Citation2017, Citation2019), have been long-standing advocates of the use of institutional theory as an alternative or complement to legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory. Over the past decade, studies using institutional theory as their main or sole analytical lens have also grown into one of the primary bodies of research within the inter-disciplinary SEA literature (Adams and Larrinaga-González Citation2019, Qian et al. Citation2021).

The debates about the roles of theories and theorising in the SEA literature have partly been permeated by a sense of unease about its tendency to privilege radical critiques, aimed at engendering an emancipatory agenda, over robust theory development but also its alleged failure to apply popular theories in ways that are truly conducive to the advancement of such critiques. Several prominent SEA scholars have voiced such concerns (Gray Citation2002, Spence et al. Citation2010, Unerman and Chapman Citation2014, O’Dwyer and Unerman Citation2016). Reflecting on early advances in the field, Gray (Citation2002) lamented the lack of explicit and sophisticated theorisation of accounting practices in much SEA research while noting how attempts to advance radical critiques of such practices started to emerge in the 1990s. Sharpening this criticism, Spence et al. (Citation2010) attacked the subsequent tendency among SEA scholars to increasingly borrow theories with critical potential from other fields of research while domesticating, if not outright misappropriating, them in their efforts to make sense of accounting as an organisational and social practice. This borrowing of theories, they argue, has more to do with the mimicking of scientific practices that are seen as popular, or well-established, in cognate fields of research than a genuine aspiration to make research critical. Similarly, more recent commentaries have continued to fret about the alleged lack of robust theory development while being careful to point out that such theory development does not necessarily preclude the advancement of more or less radical critiques (Unerman and Chapman Citation2014, O’Dwyer and Unerman Citation2016). These long-standing criticisms are worth taking seriously to ensure that any attempts to enhance the theoretical sophistication of the SEA project do not occur at the expense of its transformative potential and reinforce a development that turns it into a politically anodyne, if not conservative, body of research. Such concerns are particularly pertinent in the light of recurring debates suggesting that, despite its critical potential, this project is continuously at risk of losing its radical edge and being confined to an essentially reformist agenda characterised by pragmatism and political quietism (e.g. Tinker et al. Citation1991, Gray Citation2002, Gray et al. Citation2018, Bigoni and Mohammed Citation2023, Descalzo et al. Citation2023, Husillos Citation2023, Tweedie Citation2023a, Citation2023b).

Even though criticisms of the SEA project such as those outlined above have not been specifically targeted at the growing popularity of institutional theory, they need to be borne in mind as we engage with this theory. While some commentators argue that institutional theory has always had an immanent critical potential as it emerged as a distinct counterpoint to functionalist accounts of organisations that privilege managerial interests (e.g. Suddaby Citation2015, Drori Citation2020), the question of whether this potential has been or can indeed be realised has been extensively debated in the organisation studies literature. Both sceptical (e.g. Cooper et al. Citation2008, Willmott Citation2011, Citation2015, Citation2019) and sympathetic voices (e.g. Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006, Hirsch and Lounsbury Citation2015, Lok Citation2019) have been raised, suggesting that there is little consensus about whether or not institutional theory can be critical. At the heart of these debates lies the issue of whether institutional theory has been explicitly concerned with questions of power and how power struggles around and within organisations lead particular concerns and interests to be entrenched or marginalised (Clegg Citation2010, Zald and Lounsbury Citation2010, Munir Citation2015, Citation2020). While notions of power are arguably a ubiquitous feature of institutions, critics suggest that critical interrogations of its role in organisations and society have been over-shadowed by the constant efforts to extend and refine institutional theory in a never-ending quest for theoretical sophistication (Cooper et al. Citation2008, Willmott Citation2011, Citation2015, Citation2019). However, other scholars have taken a less pessimistic view and have argued that the conceptual development of institutional theory has indeed sensitised it to questions of power and the possibilities of emancipation (Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006, Lawrence et al. Citation2009, Citation2011, Hirsch and Lounsbury Citation2015). Similar sentiments have emerged in the accounting literature and have drawn attention to the theoretical premises that need to be in place to make institutional theory conducive to more explicit, critical analyses of power (Modell Citation2015, Citation2022a). While institutional theory is not the only theory that can further our understanding of power, paying due heed to these premises is arguably important to help realising the critical potential of the SEA project. Given the growing popularity of institutional theory as a basis for SEA research, there is an imminent risk of this potential being further eroded unless researchers engage with conceptual developments that have aimed at exploring how power struggles entrench and marginalise various interests and influence the possibilities of emancipation.

The discussion above raises the question of how SEA scholars have used institutional theory and to what extent this has helped or hindered in furthering the SEA project as a critical research programme that is concerned with questions of power and the possibilities of emancipation. We address this research question through a review of SEA research based on institutional theory. We find that very little of this research has sought to imbue institutional analyses with explicit, critical intent and corresponding analyses of power. It can, therefore, hardly be said to have furthered the development of the SEA project in a direction aimed at engendering radical, emancipatory critiques. However, contrary to earlier criticisms of institutional theory, suggesting that this lack of critical intent is due to an ambition to constantly prioritise theory development over critique, there is little ground for arguing that this is the case in the SEA literature. Instead, we find more merit in a line of argument resembling that levied at the SEA literature for lacking theoretical sophistication and that it is this lack of conceptual development that has detracted from its critical potential. Insofar as SEA scholars have used institutional theory, they have mainly applied received and, in many cases, dated versions of the theory to different accounting topics while rarely engaging with conceptual developments aimed at realising its critical potential. We discuss how this situation may be rectified by drawing attention to a number of ways in which SEA research may both contribute to the conceptual development of institutional theory and advance research in a critical direction.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. We start by outlining key conceptual developments in institutional theory and how it may be turned into a critical research programme and develop an analytical framework guiding the rest of the paper. We then review the use of institutional theory in the SEA literature with an eye to how researchers have mobilised different strands of the theory and whether each of these strands has contributed to making research critical. We conclude the paper with a summary of our findings and a discussion of implications for future research.

2. The development of institutional theory

2.1 Key conceptual developments in institutional theory

Throughout its long history, institutional theory has subscribed to a pronounced normal science ideal of constantly extending and refining the theory incrementally (Cooper et al. Citation2008, Glynn and D’Aunno Citation2023). The ensuing expansion of institutional theory has turned it into a dominant strand of research in organisation studies (Greenwood et al. Citation2017) that has had a major influence on inter-disciplinary accounting research (Lounsbury Citation2008, Modell Citation2022b, Robson and Ezzamel Citation2023). In contrast to previously dominant, functionalist approaches, such as contingency theory, that examined how organisations differentiate their practices in response to diverse environments, early institutional research on accounting was heavily influenced by the seminal works of Meyer and Rowan (Citation1977) and DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) stressing the homogeneity of organisational practices. This strand of institutional theory emphasises how organisational practices that evolve within specific areas of social life, or institutional fields, gradually come to resemble each other as organisations seek to legitimise themselves to their surrounding environments and how this imbues such fields with a high degree of stability (see Scott Citation1995, Tolbert and Zucker Citation1996). Such tendencies towards homogeneity, or institutional isomorphism, have generally been underpinned by cognitive, normative and regulative forces or pillars (Scott Citation1995).Footnote2 Another central plank of this variant of institutional theory is that increasingly institutionalised practices, adopted for legitimacy-seeking purposes, are often in conflict with and thus tend to be decoupled from operating-level practices within organisations (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977). Such decoupling often takes the form of symbolic displays of various structural features that signal compliance with social conventions but which only have a marginal impact on operations and thus help to preserve a degree of stability.

While studies of institutional isomorphism and decoupling grew into a substantial body of research (Tolbert and Zucker Citation1996, Mizruchi and Fein Citation1999), it soon came under attack for over-emphasising the stability of organisations and institutional fields and downplaying questions of how human agency is implicated in transforming institutionalised practices and staking out new paths of institutional development. Starting with DiMaggio’s (Citation1988) attempt to revise the original postulates of institutional theory, institutional theorists began to pay increasing attention to how individual change agents, or institutional entrepreneurs, initiate institutional change and devise strategies for transforming individual agency into collective agency. Institutional entrepreneurs are typically defined as actors who pursue changes that deviate from institutionalised practices and mobilise resources to effectuate change within organisations or institutional fields (Hardy and Maguire Citation2008, Battilana et al. Citation2009). The increasing interest in such entrepreneurship was followed by similar conceptual advances that drew attention to the possibilities of organisations to respond strategically to institutional pressures (Oliver Citation1991) and the de-institutionalisation of institutionalised practices (Oliver Citation1992). Taken together, these advances contributed to re-orientating institutional analyses from the macro-level focus on diffusion, which underpinned much research on institutional isomorphism, to the micro-level processes involved in institutional change and the complex political dynamics associated with such processes (Greenwood et al. Citation2017, Glynn and D’Aunno Citation2023).

Following these early advances and debates within institutional theory, subsequent research has evolved along diverse strands of thought that can be broadly classified into actor-centric and structuralist approaches. Starting with the actor-centric strand of research, growing out of earlier research on institutional entrepreneurship and strategic agency, this has increasingly been dominated by studies stressing the institutional embeddedness of human agency. This research emerged in the wake of growing criticisms of earlier actor-centric approaches for subscribing to an overly voluntarist view of institutionalisation that over-emphasises the strategic or intentional nature of human agency. As an alternative to such approaches, institutional theorists started to call for detailed analyses of how intentional agency evolves without jettisoning the sense of how extant institutions condition the possibilities of such agency and institutional change (e.g. Holm Citation1995, Hirsch and Lounsbury Citation1997, Dacin et al. Citation2002, Seo and Creed Citation2002). Taking concerns with embedded agency seriously requires us to examine the intricate interplay between routine, or habitual, forms of agency that are shaped by institutionalised beliefs and values and deliberate, or reflexive, forms of agency that enable human beings to break with extant social orders in the pursuit of change (Seo and Creed Citation2002, Battilana and D’Aunno Citation2009). To enhance our understanding of the trajectories of institutional change, we also need to pay close attention to how this interplay between habitual and reflexive agency is continuously implicated in the reproduction and transformation of institutionalised practices over time (Seo and Creed Citation2002, Lawrence et al. Citation2009, Lounsbury et al. Citation2021).

One of the foremost approaches for studying embedded agency is the one pivoting on the notion of institutional work. Originally advanced by Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006, p. 215), institutional work was defined as ‘the purposive action of individuals and organizations aimed at creating, maintaining and disrupting institutions’. While institutional work thus refers to the intentional exercise of human agency, Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) were at pains to emphasise that such agency is institutionally embedded in the sense that it is constrained as well as enabled by extant institutions. In contrast to much research on institutional entrepreneurship, research on institutional work has also steered clear of the emphasis on individual change agents and has paid greater attention to collective agency as a distributed phenomenon that may emerge as a coordinated endeavour as well as on a seemingly spontaneous basis (Lawrence et al. Citation2013, Hampel et al. Citation2017). As such, the institutional work perspective is arguably well-suited for exploring the intricate micro-level dynamics and the political processes involved in the enactment, reproduction and transformation of institutionalised practices. However, criticisms have increasingly been raised that much research on institutional work has paid too much attention to such micro-level dynamics while neglecting how it is conditioned by and contributes to the shaping of broader societal orders that evolve at higher levels of analysis (Ocasio et al. Citation2017, Lounsbury et al. Citation2021).

Greater attention to how societal, macro-level orders influence the process of institutionalisation can be found in the main structuralist strand of thought, pivoting on the notion of institutional logics that currently dominates institutional theory. Originating in the work of Friedland and Alford (Citation1991), institutional logics have been defined as ‘the socially constructed, historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices, including assumptions, values, and beliefs, by which individuals and organizations provide meaning to their daily activity, organize time and space, and reproduce their lives and experiences’ (Thornton et al. Citation2012, p. 2). Similar to prior research on institutional isomorphism, such logics are seen as a powerful structural force that imbues institutional fields with a sense of order by establishing relatively enduring patterns of organisational behaviour. However, in contrast to the structural determinism often associated with such isomorphism, institutional logics are neither impervious to change nor necessarily a source of standardisation in institutional fields. While early research on institutional logics documented how certain fields underwent radical change, that is manifest in relatively complete shifts between dominant logics (e.g. Haveman and Rao Citation1997, Thornton and Ocasio Citation1999, Lounsbury Citation2002), more recent advances have focused on how competing logics may continue to co-exist over extended periods of time and breed variations in organisational practices (e.g. Lounsbury Citation2007, Marquis and Lounsbury Citation2007, Reay and Hinings Citation2009). Hence, the institutional logics perspective has evolved into a research programme where notions of institutional complexity and heterogeneity play a central role (Lounsbury Citation2008, Greenwood et al. Citation2011, Thornton et al. Citation2012).

In advancing the institutional logics perspective, propagators of this perspective have also laid claims to a sophisticated theory of human agency that neither subsumes such agency under structural categories nor imbues it with an exaggerated sense of volition (Lounsbury and Ventresca Citation2003, Thornton et al. Citation2012). Rather, human agency is seen as conditioned by extant and emerging logics while allowing for the possibility that human beings can sometimes engage reflexively with such logics and thereby make creative use of them in devising organisational practices. The institutional logics perspective is therefore imbued with a strong sense of embedded agency that needs to take centre stage in empirical analyses of how institutionalised practices are enacted, reproduced and transformed (Ocasio et al. Citation2017, Lounsbury et al. Citation2021, Perkmann et al. Citation2022). Failing to do so implies a risk of following what Lounsbury et al. (Citation2021) call a toolkit approach that treats institutional logics as little more than analytical archetypes without accounting for the complex processes through which they come to influence organisational practices and imbue such practices with context-specific meanings. This may, in turn, lead to analytical reification of institutional logics and a situation where researchers refrain from deeper inquiries into their role as templates for action in organisations and institutional fields.

To summarise the conceptual developments in institutional theory, it has evolved from diverse approaches that placed relatively one-sided emphasis on isomorphism and stability, on the one hand, and agency and change, on the other, to a body of research that is united by a strong emphasis on embedded agency and a view of institutionalised practices as potentially subject to reproduction as well as transformation. Even though actor-centric approaches, such as research on institutional work, and structuralist approaches, such as the institutional logics perspective, differ somewhat in their relative emphasis on institutionalisation as a micro- and macro-level phenomenon, they share a view of human agency as conditioned by extant and emerging institutions without jettisoning the possibilities of deliberate, or reflexive, agency. Without a focus on embedded agency, SEA research can hardly be said to have kept up with the evolution of institutional theory. Indeed, as Modell (Citation2022b) recently observed, without such a focus, institutional accounting research is likely to degenerate into either the determinism or voluntarism associated with earlier variants of institutional theory. Therefore, an emphasis on embedded agency arguably needs to constitute the bedrock of any attempts to extend and refine such research or, for that matter, institutional theory in general (cf. Heugens and Lander Citation2009, Greenwood et al. Citation2017, Perkmann et al. Citation2022). Failing to do so would be inconsistent with the incremental view of theory development associated with the normal science ideal informing institutional theory. As explicated below, a focus on embedded agency also has important implications for the ways in which institutional theory can be turned into a critical research programme.

2.2 Institutional theory as a critical research programme

Parallel to the conceptual developments in institutional theory described above, the issue of whether institutional research can be critical has been extensively debated. While several commentators argue that institutional theory can be imbued with critical or emancipatory intent (Lounsbury Citation2003, Lawrence and Suddaby Citation2006, Zald and Lounsbury Citation2010, Hirsch and Lounsbury Citation2015, Lok Citation2019), others have posited that the efforts to develop such intent have been overshadowed by the fundamentally conservative epistemology that is embedded in the normal science ideal of constantly extending and refining the theory (Cooper et al. Citation2008, Clegg Citation2010, Willmott Citation2011, Citation2015, Citation2019). This normal science ideal arguably detracts from more engaged forms of scholarship involving efforts to further marginalised concerns and interests in organisations and society. This reinforces the politically anodyne nature of institutional theory that emanates from its alleged reluctance to put power centre stage. According to Clegg (Citation2010), explicit concerns with power have been missing in much institutional research due to the propensity of institutional theorists to subjugate such concerns to their preoccupation with the cognitive and normative aspects of institutionalisation. These tendencies were especially prevalent in the early research on institutional isomorphism, which privileged such aspects over focused attention to the regulative, or coercive, powers underpinning such isomorphism (see also Mizruchi and Fein Citation1999). Even though conceptual and empirical advances aimed at making concerns with power an integral part of institutional analyses have since emerged (Lawrence Citation2008, Lawrence and Buchanan Citation2017), the debate about whether this has helped to imbue institutional theory with explicit, critical intent has continued (Munir Citation2015, Citation2020). We review these developments and the concomitant discussions of how how power should be conceptualised to further a critical research agenda.

The most concerted efforts to make institutional theory critical can be found in the literature on institutional work. From the outset, Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) sought to develop this strand of institutional thought in a direction where attention to disenfranchised constituencies in organisations and institutional fields plays a prominent role and where the possibilities of emancipation from oppressive, institutionalised practices are brought to the fore. To this end, they proposed a dynamic and relational view of power that does not treat it as an analytical category that automatically belongs to certain actors but that is continuously negotiated among the actors involved in the process of institutionalisation. Through such processes of negotiation, power relations may be re-configured in such a way that they come to challenge the entrenched positions of social elites and favour the interests of marginalised constituencies (see also Lawrence et al. Citation2009, Citation2011). However, this conception of power has been criticised for subscribing to an overly actor-centric view of institutionalisation that, at worst, jeopardises the emphasis on embedded agency that is a central plank of the institutional work perspective (Willmott Citation2011, Citation2015, Modell Citation2022a). This may, in turn, lead to a view of power as primarily exercised through discrete acts of an intentional nature, or what Lawrence (Citation2008) calls episodic power, and exaggerated accounts of the possibilities of disenfranchised actors to dis-embed themselves from oppressive states of affairs in their pursuit of emancipation. To mitigate the risk of jettisoning notions of embedded agency, there also need to be some concerns with what Lawrence (Citation2008) calls systemic power, which denotes the more unobtrusive forms of power that operate through institutionalised beliefs and values and shape people’s cognition. Such power tends to fill a stabilising role that moderates the exercise of episodic power. An overly actor-centric perspective on institutionalisation can also detract from the large-scale, structural changes that may be required for tendencies towards marginalisation to be remedied. Even scholars who are sympathetic to the efforts to make institutional theory critical argue that the propensity to foreground human agency as the primary source of power in much institutional research is likely to lead to an emphasis on relatively small-scale, micro-level attempts to change institutionalised practices rather than radical challenges to the macro-level orders that perpetuate tendencies towards marginalisation in organisations and institutional fields (Lok Citation2019).

Greater attention to how macro-level orders condition the possibilities of radical social critique and emancipation can be found in the literature on institutional logics. Several scholars have begun to harness the institutional logics perspective to pursue such critiques (Hirsch and Lounsbury Citation2015, Amis et al. Citation2017, Gümüsay et al. Citation2020, Lounsbury and Wang Citation2020). The institutional logics perspective is arguably well-suited to this task, given its origins in Friedland and Alford’s (Citation1991) attempt to bring society as a macro-level construct back into institutional analyses. Institutional logics are generally seen as rooted in broader societal orders, such as the corporation, the market and the state, which take concrete, context-specific form in institutional fields and individual organisations within such fields (Thornton et al. Citation2012, Ocasio et al. Citation2017). Such orders define what is seen as problematic and what constitutes legitimate means of solving particular societal problems (Amis et al. Citation2017), while their translation in specific social contexts imbues problems and solutions with context-specific meanings that require close attention to further our understanding of how questions of emancipation can be tackled across different local settings (Gümüsay et al. Citation2020). The capacity of institutional logics to define problems and legitimate solutions and, by implication, marginalise competing concerns can be an important source of power in organisations and institutional fields. However, the power associated with such logics is often of a tacit or unobtrusive nature as it works through cognition rather than discrete acts of influence, force or resistance (Marquis and Lounsbury Citation2007, Thornton et al. Citation2012, Sadeh and Zilber Citation2019). In other words, the power that is embedded in institutional logics is typically of a systemic nature even though actors may, under certain circumstances, engage reflexively with such logics and turn reflexivity into a source of episodic power. As such, the institutional logics perspective provides a potential counterweight to overly actor-centric and possibly exaggerated conceptions of the possibilities of critique and emancipation that downplay notions of embedded agency (Hirsch and Lounsbury Citation2015, Lounsbury and Wang Citation2020). Even though it does not rule out the possibility of actors pursuing deliberate strategies of change and resistance, it insists on the need for institutional analyses to be sensitive to the ways in which diverse logics condition these possibilities.

The above discussion illustrates how the conceptual developments in institutional theory emerging over the last two decades have contributed to imbuing at least parts of this research programme with increasingly explicit, critical intent or potential. However, the question of whether the nurturing of such intent can be reconciled with the normal science ideal of constantly extending and refining institutional theory remains unresolved. While critics of institutional theory have argued that such reconciliation is close to impossible (Cooper et al. Citation2008, Willmott Citation2011, Citation2015, Citation2019), others have been more sanguine in this regard (Lok Citation2019). However, for such reconciliation to be possible, research needs to be conducted in ways that preserve the conceptual underpinnings of institutional theory and remain faithful to its continuous evolution (Modell Citation2015, Lok Citation2019). Although we are not arguing that there is an irreconcilable conflict between the normal science aspirations of institutional theorists and the efforts to make institutional theory critical, close attention is required to a number of key, conceptual developments for reconciliation to be possible. Particular care is required such that any attempts to advance a focus on changes that further marginalised concerns and interests are combined with a strong sense of human agency as an institutionally embedded phenomenon. While such changes often require an element of pro-active, human intervention and a break with institutionalised practices that reinforce marginalisation, researchers need to be wary of jettisoning the focus on embedded agency as a result of an excessive emphasis on episodic power which has arguably been the case in much research on institutional work. At the same time, for institutional research to be imbued with explicit, critical intent, notions of power need to be explicitly theorised even if they are of a largely tacit or unobtrusive nature as is the case in the institutional logics perspective. Failures to do so may perpetuate the tendency to downplay notions of power and how it is implicated in processes of marginalisation and emancipation in much earlier institutional research (Clegg Citation2010).

2.3 Analytical framework

The above discussion leads us to advance a framework for analysing how SEA scholars have used institutional theory and how this has affected the advancement of the SEA project as a critical research programme. We address these questions by mapping research along two analytical dimensions reflecting (1) the extent to which researchers have had the ambition to develop institutional theory conceptually and the extent to which this has been coupled with (2) an ambition to advance research in a critical direction (see ).

Insofar as the conceptual development of institutional theory is concerned, a key issue is whether SEA scholars have kept up with the increasing emphasis on embedded agency and how such agency is implicated in the enactment, reproduction and transformation of institutionalised practices. As we have seen, concerns with such agency have emerged as a key, unifying feature of institutional theory over the past two decades and, in accordance with its normal science aspirations, such concerns need to form a stepping stone for any attempts to extend and refine the theory. However, such attempts to extend and refine institutional theory do not guarantee that authors also strive to advance institutional research in a critical direction. Following the more general criticism of institutional theory for privileging theory development over critique, it may well be that SEA scholars are following a similar path and thus reduce the radical, transformative potential of the SEA project (upper left-hand quadrant in ). While such tendencies would run counter to the criticism that SEA scholars have paid more attention to the advancement of critique than theory development, this might change insofar as they fall under the spell of constantly advancing theory that is inherent in much institutional research. Alternatively, they may end up scoring low on both the conceptual development and critical dimensions by, for example, using dated or misappropriated versions of institutional theory that are devoid of critical intent (lower left-hand quadrant in ). Also, as we have seen above, failures to keep up with the conceptual development of institutional theory may be reinforced as researchers strive to make it critical (lower right-hand quadrant in ). This would be the case if authors advance critical lines of argument, focusing on how the exercise of power is implicated in processes of marginalisation and how this may be rectified, while jettisoning notions of embedded agency. For research to embody a high ambition to develop institutional theory conceptually as well as advancing research in a critical direction (upper right-hand quadrant in ), concerns with the exercise of power need to be combined with explicit concerns with embedded agency as a basis for extending or refining the theory. Hence, while the attempts to imbue institutional research with critical intent can take different forms, it is relevant to explore the extent to which this has been coupled with an emphasis on embedded agency and how such agency is implicated in the exercise of power.

3. Institutional research on social and environmental accounting

3.1 Scope of review and review procedures

Given the purpose of our paper, we combine elements of a systematic literature review (Elsbach and van Knippenberg Citation2020, Simsek et al. Citation2023) with those of a problematising review (Alvesson and Sandberg Citation2020) that aims at interrogating whether or not institutional research on SEA has been imbued with critical intent. Given the lack of consensus about whether institutional theory can be critical, we adopted an a priori position of agnosticism as to whether it has hampered or stimulated such a development in the SEA literature. While we recognise the potential conflict between the normal science ideal of constantly extending and refining institutional theory and imbuing it with critical intent, we kept an open mind as to whether and how this conflict has been resolved in the studies under review. On this basis, we sought to map how SEA scholars have used institutional theory and whether this has helped or hindered in furthering the SEA project as a critical research programme.

To identify the sample of studies under review, we mainly followed a journal-driven approach (Hiebl Citation2023a, Citation2023b). To control for journal quality, we confined the selection of journals to those ranked at levels three and four of the Chartered Association of Business Schools’ Academic Journal Guide. To keep the number of studies at a manageable level, we further restricted the selection of publication outlets to eleven journals that have been or may be expected to regularly publish inter-disciplinary research on SEA.Footnote3 However, to validate these search procedures and assess whether the studies published in the eleven journals are representative of how institutional theory has been used in the SEA literature, we complemented the journal-based searches with broader, database-driven searches using Google Scholar and Scopus as our primary search engines. A combination of search terms reflecting key themes in the SEA literature and institutional theory was used for all searches.Footnote4 The main literature search was completed in February 2023, but we continuously kept our review updated to ensure that any additional relevant studies published after this date were included in our sample.

Following these search procedures, we eventually ended up with a sample of 86 studies deemed relevant for inclusion in our review. As is typical of journal-driven approaches to sample selection, we recognise that our selection procedures detract somewhat from the comprehensiveness of our review (Hiebl Citation2023a, Citation2023b). However, this should be weighed against the added depth and rigour that follow from only selecting studies published in highly ranked journals (Simsek et al. Citation2023, Hiebl Citation2023a). Judging from our complementary, database-driven searches, we believe our sample broadly represents how institutional theory has been used in the SEA literature. While we did not set any time limits for our review, our literature search confirms that institutional research on SEA has mainly evolved since the early 2000s and that it has grown very rapidly over the last decade (cf. Adams and Larrinaga-González Citation2019, Qian et al. Citation2021).

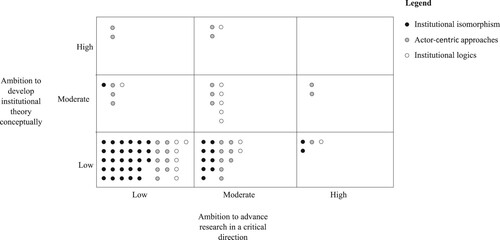

In coding the studies under review, we took our point of departure in the analytical framework advanced above while using somewhat more granular scales for assessing the extent to which researchers seek to develop institutional theory conceptually and advance research in a critical direction. Given the growing centrality of embedded agency as a unifying concept in institutional theory that guards against excessive determinism and voluntarism while enhancing our understanding of the possibilities of institutional change, we took this as our main reference point for determining the ambition to develop this theory conceptually. Studies were coded low if they merely apply structuralist approaches, centred on institutional isomorphism or institutional logics, or actor-centric approaches, using notions of institutional entrepreneurship, strategic agency or institutional work, without featuring explicit concerns with embedded agency and the conditions under which actors can break with institutionalised practices in their attempts to initiate change. Studies recognising questions of embedded agency and examining how such agency is implicated in the reproduction and/or transformation of accounting practices were coded as imbued with a moderate ambition to develop institutional theory. However, for studies to be coded high on this dimension, they need to build on such conceptions of agency to advance conceptual extensions or refinements that not only advance SEA research but also make a distinct, incremental contribution to institutional theory in general. Reserving this code for studies that make such contributions follows from Modell’s (Citation2022b) observation that many accounting scholars are content to mainly apply received versions of institutional theory to various accounting topics and that they do not always strive to advance this theory conceptually. This coding practice also captures the extent to which SEA scholars have been influenced by the normal science ideal of constantly extending and refining theory to which institutional theorists subscribe (Cooper et al. Citation2008, Glynn and D’Aunno Citation2023).

As to the ambition to advance research in a critical direction, studies were coded low if they offer no ostensible insights into the role of power in institutional processes or discuss power in ways that are not imbued with critical intent. A key indication of whether such intent is present is whether authors discuss the implications of their findings for policy development with the potential to further concerns with economic and social equity and sustainability that are at risk of being marginalised in organisations and society. If this was found to be the case and the studies offer at least some reflections on the role of power in institutional processes, they were coded as imbued with a moderate ambition to advance research in a critical direction. However, for studies to be coded high on this dimension, they need to entail an explicit ambition to make institutional theory critical and pay ample attention to the exercise of power as an integral part of their analyses and discussions of policy implications. Reserving this code for studies that entail such an ambition is consistent with the criticism that much institutional research is not imbued with explicit, critical intent (Cooper et al. Citation2008, Clegg Citation2010, Willmott Citation2011, Citation2015, Citation2019) and facilitates our analysis of whether it is possible to develop such intent while simultaneously complying with the normal science ideal of constantly extending and refining theory.

Following these criteria for determining the ambition to develop institutional theory conceptually and advance research in a critical direction, each study was first coded independently by two of the authors of this paper. The individual codes were then compared, and coding discrepancies were resolved through discussions until a consensus interpretation was found. At this stage, the third author, who was not involved in the initial coding, occasionally intervened as an arbiter to resolve coding discrepancies. The average initial rate of agreement between the coders before coding discrepancies were resolved was 90%, which compares favourably with similar attempts to take stock of institutional research on accounting (Modell Citation2022b). An overview of our final coding of the 86 studies can be found in the Online Appendix.

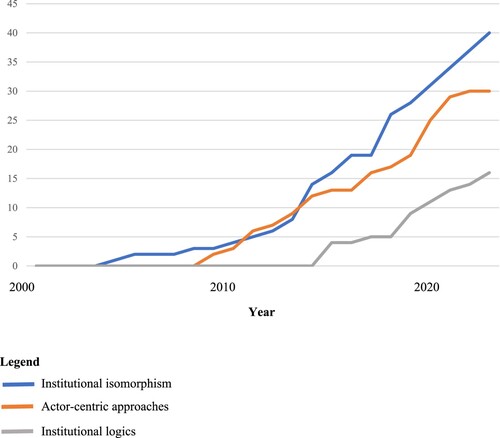

We organise our review into three relatively distinct categories of research that follow from our outline of the evolution of institutional theory. Studies were classified as relying on (1) institutional isomorphism, (2) actor-centric approaches and (3) institutional logics as the primary basis for their analysis of SEA practices. depicts the accumulation of research across the three groups over time. As can be seen, the dominant and still growing category, accounting for nearly half of the studies under review, is that exploring notions of institutional isomorphism. Alongside this research, a somewhat smaller but still substantial group of studies based on various actor-centric approaches has evolved. Finally, over the last decade, research mobilising the institutional logics perspective has grown rapidly (see also Contrafatto Citation2022), although it still represents the smallest category of research in our review. Overall, this pattern resembles that found in other parts of the accounting literature relying on institutional theory (Modell Citation2022b), even though SEA scholars have been comparatively late in adopting this theory. The coding of the studies falling into the three categories is summarised in . In what follows, we discuss each of these categories of research in greater detail.

3.2 Institutional isomorphism

Starting with the studies that mainly explore the influence of institutional isomorphism, most of this work closely follows DiMaggio and Powell’s (Citation1983) original conceptualisation and/or Scott’s (Citation1995) elaboration of their framework focusing on the institutional pillars that underpin such isomorphism. In doing so, researchers have started to document how SEA practices are becoming increasingly similar or standardised within and sometimes across institutional fields. A number of studies have extended the theorisation by paying systematic attention to how variations in such practices can emerge despite the prevalence of isomorphic pressures (e.g. Perez-Batres et al. Citation2010, Qian et al. Citation2011, Zeng et al. Citation2012, Christ Citation2014, Searcy and Buslovich Citation2014, Campopiano and de Masis Citation2015, Adams et al. Citation2016, Chatelain-Ponroy and Morin-Delerm Citation2016, Baldini et al. Citation2018, Comyns Citation2018, Heggen et al. Citation2018, Parsa et al. Citation2021, Al-DosAri et al. Citation2023, Derchi et al. Citation2023, Lopatta et al. Citation2023). However, when explaining why such practice variations occur, they do not engage with more recent advances in institutional theory, such as the institutional logics perspective, that have arguably refined our understanding of the institutional sources of heterogeneity (see Lounsbury Citation2008). Moreover, for reasons specified below, there is typically only limited, if any, attention to the human agency involved in the enactment, reproduction and transformation of institutionalised accounting practices and very little engagement with questions of embedded agency. Hence, the ambition to develop institutional theory conceptually is, for the most part, low or, at best, moderate.

There are several reasons why many studies have not ventured significantly beyond the notion of institutional isomorphism in explaining the development of SEA practices. One reason is the way SEA scholars position institutional theory vis-à-vis other theories when motivating their choice of theories. A large number of studies motivate the choice of institutional theory as an alternative (Qian et al. Citation2011, de Aguiar and Bebbington Citation2014, Comyns Citation2016) or, more frequently, complement to legitimacy theory and/or stakeholder theory (Islam and Deegan Citation2008, Beddewela and Herzig Citation2013, Momin and Parker Citation2013, Chelli et al. Citation2014, Searcy and Buslovich Citation2014, Campopiano and de Massis Citation2015, Chatelain-Ponroy and Morin-Delerm Citation2016, Baldini et al. Citation2018, Russo-Spena et al. Citation2018, Gaia and Jones Citation2020, Eliwa et al. Citation2021, Ruiz-Lozano et al. Citation2022, Thoradeniya et al. Citation2022, Roy et al. Citation2023, Lopatta et al. Citation2023). Echoing arguments put forward in earlier discussions of the role of theory in the SEA literature (e.g. Deegan Citation2006, Adams and Larrinaga-González Citation2007, Chen and Roberts Citation2010), institutional theory is often presented as a valuable structuralist perspective as opposed to the emphasis on strategic management of legitimacy and stakeholder relations in research informed by legitimacy and stakeholder theory. While recognising the similarities and partial overlaps between the three theories, institutional theory is typically seen as a preferred perspective for enhancing our understanding of how broader societal expectations and conventions that are manifest in isomorphic pressures shape accounting practices and imbue such practices with a degree of stability. However, insofar as the interplay between isomorphic pressures and strategic management is actually subjected to deeper analysis, this juxtaposition of institutional theory and cognate theories does little to advance our understanding of human agency as a phenomenon that is institutionally embedded. For instance, Momin and Parker (Citation2013) advanced a framework outlining how such pressures interact with the legitimacy-seeking strategies of subsidiaries of multi-national corporations but only offered limited empirical insights into the intricacies of mobilising agency in the face of conflicting institutional pressures. Similarly, integrating insights from institutional theory and stakeholder theory, Roy et al. (Citation2023) paid more explicit attention to the agency exercised by such subsidiaries in responding to institutional isomorphism and stakeholder pressures but failed to conceptualise these responses in terms of embedded agency or examine how such agency unfolds over time.

A similar tendency for the juxtaposition of theories to hamper the propensity of SEA scholars to go beyond the conception of institutional theory as a structuralist perspective, which is primarily concerned with institutional isomorphism, is obvious in studies combining it with functionalist perspectives such as contingency theory (Qian et al. Citation2011, Christ Citation2014), strategic management theories (Griffin and Youm Citation2018, Russo-Spena et al. Citation2018, Derchi et al. Citation2023) and various economic theories (Cormier et al. Citation2005, Briem and Wald Citation2018, Gaia and Jones, Citation2020, Eliwa et al. Citation2021). The use of institutional theory in these studies is generally limited to the identification of factors and variables representing different types of isomorphism, which are then combined with factors and variables derived from other theories and integrated as conceptual building blocks in analytical models. This focus on merely deriving basic, conceptual building blocks from different theories detracts from deeper engagements with institutional theory and its evolution over time. As a result, any concerns with the agency involved in the enactment, reproduction and transformation of institutionalised accounting practices are effectively bracketed. The only exception to this pattern is Briem and Wald’s (Citation2018) study, which examined the role of auditors as change agents in the establishment of third-party assurance of integrated reporting practices and how this reinforces isomorphic pressures. However, even in their case, little attention was being paid to the institutionalised beliefs and values that compel auditors to enact such a role. Hence, even though Briem and Wald (Citation2018) provide a relatively detailed account of the strategies employed by auditors in establishing different forms of assurance, they did not engage with notions of embedded agency.

Another reason for the failure of much institutional research on SEA to move beyond notions of institutional isomorphism and examine the role of embedded agency in the process of institutionalisation can be found in its choice of substantive, empirical research topics and the types of research questions that are being asked. The vast majority of the studies exploring the influence of institutional isomorphism are disclosure studies that pay little attention to intra-organisational processes in explaining what drives organisations to report social and environmental information (e.g. Perez-Batres et al. Citation2010, Zeng et al. Citation2012, de Villiers and Alexander Citation2014, Campopiano and de Massis Citation2015, Comyns Citation2016, Citation2018, Griffin and Youm Citation2018, Parsa et al. Citation2021, Thoradeniya et al. Citation2022) or adapt their reporting practices to changing societal expectations that are manifest in such isomorphism (e.g. Islam and Deegan Citation2008, Beddewela and Herzig Citation2013, de Aguiar and Bebbington Citation2014, Briem and Wald Citation2018, Chelli et al. Citation2014, Russo-Spena et al. Citation2018, Sidhu and Gibbon Citation2021, Sorour et al. Citation2021). While notions of institutional isomorphism are an appropriate starting point for analysing such topics, the lack of attention to intra-organisational processes implies that the agency involved in the choice of reporting practices and the translation of such reporting practices within organisations only receives cursory attention. Some authors draw attention to how isomorphic pressures interact with organisation-specific and/or individual-level characteristics in shaping reporting practices (e.g. Zeng et al. Citation2012, Beddewela and Herzig Citation2013, Searcy and Buslovich Citation2014, Comyns Citation2018, Thoradeniya et al. Citation2022). However, even where this is the case, the discussion is not framed in terms of how organisational responses to isomorphic pressures may be understood as manifestations of human agency or how such agency is conditioned by the institutions in which it is embedded. The limited attention to intra-organisational factors also means that few insights are provided into whether or not SEA practices are decoupled from operating-level practices. Given the central position of the notion of decoupling in institutional theory, this reinforces the impression that many SEA scholars have not only failed to keep up with its development over time but also that they have made relatively limited and selective use of this theory when examining social and environmental disclosures.

A final reason for the preoccupation with institutional isomorphism and lack of attention to embedded agency is the research methods that are being employed. Most research examining the influence of such isomorphism on social and environmental disclosures has been based on qualitative content analyses of publicly available reports (e.g. Chelli et al. Citation2014, de Aguiar and Bebbington Citation2014, Campopiano and de Massis Citation2015, O’Neill et al. Citation2015, Baldini et al. Citation2018, Christ et al. Citation2019), quantitative, archival methods (e.g. Perez-Batres et al. Citation2010, Zeng et al. Citation2012, de Villiers and Alexander Citation2014, Comyns Citation2016, Griffin and Youm Citation2018, Lopatta et al. Citation2023) and cross-sectional field studies covering a relatively large number of organisations (e.g. Beddevela and Herzig Citation2013, Searcy and Buslovich Citation2014, Briem and Wald Citation2018, Parsa et al. Citation2021, Thoradeniya et al. Citation2022, Roy et al. Citation2023). Such methods are appropriate for mapping broad patterns in social and environmental disclosures across organisations but are much less suited for delving into the complex processes through which human agency becomes implicated in the enactment, reproduction and transformation of institutionalised practices. Among the studies primarily concerned with the influence of institutional isomorphism, only a handful are deeper case studies in individual or a smaller number of organisations (Rahaman et al. Citation2004, Contrafatto Citation2014, Heggen et al. Citation2018, Li and Belal Citation2018). These studies offer detailed analyses of how external reporting practices influence and interact with accounting and control practices within organisations. However, in terms of theory development, they are still mainly concerned with how different types of isomorphic pressures come to permeate intra-organisational practices while relatively limited attention is being paid to the agency involved in reproducing and transforming such practices over time. The only exception to this pattern is Contrafatto’s (Citation2014) longitudinal analysis of how the accounting rules laid down in the external reporting templates of an Italian company were gradually translated into intra-organisational routines and how this process was reinforced by the agency exercised by key organisational actors who were strongly committed to notions of sustainability due to their professional backgrounds. As such, his analysis is characterised by a relatively balanced emphasis on institutional isomorphism and embedded agency while documenting the intricate interplay between the two as they unfolded over time.

The limited ambition to develop institutional theory conceptually is mirrored by an equally modest ambition to advance research in a critical direction. With a small number of exceptions (Rahaman et al. Citation2004, Leong and Hazelton Citation2019), it is difficult to discern any clearly articulated aspirations to turn the insights offered by institutional theory into radical critiques that are concerned with how economic and social equity and sustainability may be furthered. A number of studies discuss the policy implications of their findings and call for a greater element of mandatory regulation of social and environmental disclosures (e.g. Baldini et al. Citation2018, Gaia and Jones, Citation2020, Haque and Jones Citation2020, Eliwa et al. Citation2021, Parsa et al. Citation2021, Ruiz-Lozano et al. Citation2022) or problematise how such regulation has worked or might work in specific contexts (e.g. Zeng et al. Citation2012, Beddewela and Herzig Citation2013, Chelli et al. Citation2014, Christ Citation2014, Comyns Citation2018, Sidhu and Gibbon Citation2021, Lopatta et al. Citation2023). These observations contradict Clegg’s (Citation2010) criticism that much institutional research has downplayed the regulative, or coercive, aspects of institutional processes in favour of the cognitive and normative dimensions of such processes. However, the discussions of policy implications are generally limited by the fact that they are rarely integrated with any attempts to explicitly theorise the role of power as a source of institutional change. Insofar as issues related to power are made explicit, they have mainly been discussed in terms of power differentials between institutional constituencies that espouse various types of isomorphism and how extant power imbalances affect SEA practices (e.g. Islam and Deegan Citation2008, Momin and Parker Citation2013, de Villiers and Alexander Citation2014, Baldini et al. Citation2018, Griffin and Youm Citation2018, Li and Belal Citation2018, Gaia and Jones, Citation2020, Parsa et al. Citation2021, Sidhu and Gibbon Citation2021, Roy et al. Citation2023, Thoradeniya et al. Citation2022). When combined with a lack of attention to the human agency involved in institutional processes, such conceptions of power testify to a relatively static view of power relations and provide few insights into how such relations may be altered in the pursuit of enhanced equity and sustainability (Lawrence Citation2008, Lawrence and Buchanan Citation2017).

Similar to the concerns with regulation in the studies reviewed above, SEA scholars seeking to imbue institutional analyses with more explicit, critical intent have paid ample attention to how such regulation may be seen as a manifestation of coercive pressures. However, in doing so, they expand the discussion to examine how the power associated with such pressures may be reinforced by other types of isomorphism and how this can contribute to marginalising concerns with equity and sustainability. Rahaman et al. (Citation2004) documented how the coercive powers of the World Bank led the accounting practices of a utility provider in a less-developed country to have detrimental effects on local communities and how this development was reinforced by the normative pressures exerted by the accounting profession. Motivated by an explicit ambition to make institutional theory critical,Footnote5 they also drew attention to how the ensuing popular protests and power struggles created a legitimation crisis that threatened to undermine the position of the World Bank as a champion of economic and social equity and sustainability. This understanding of how power may operate in institutional fields led Rahaman et al. (Citation2004) to advance nuanced policy recommendations for how such legitimation crises may be avoided. Similarly, Leong and Hazelton (Citation2019) debated how the coercive powers associated with the increasing reliance on mandatory regulation of social and environmental reporting may be reinforced by other forms of isomorphism and how this may contribute to institutionalise concerns with equity and sustainability in organisations and society. In doing so, they criticised the excessive emphasis on the responses of individual organisations in prior institutional research on SEA and the alleged failure of institutionalised reporting practices to produce equitable and sustainable societies. Extending this line of argument, Leong and Hazelton (Citation2019) argued that, for such wider, societal effects to materialise, reports may need to be aggregated beyond individual organisations. This may be seen as an attempt to take critical, macro-level concerns more seriously than has been the case in prior institutional research on social and environmental disclosures. Yet, similar to most of this research, both Rahaman et al. (Citation2004) and Leong and Hazelton (Citation2019) saw power as a phenomenon that predominantly resides in different types of isomorphism and thus left its dynamic and relational properties under-theorised.

To summarise, it is clear that much SEA research informed by institutional theory has done little to develop this theory beyond its original but now dated emphasis on institutional isomorphism and that the focus on such isomorphism has rarely been accompanied by attempts to advance research in a critical direction. A particular concern is how this analytical focus and the accompanying lack of attention to the human agency involved in institutional processes have cemented a view of power as a relatively static phenomenon that is closely associated with especially the regulative, or coercive, aspects of institutionalisation. This detracts from our understanding of how power relations may be altered and how a focus on such changes may imbue institutional research on SEA with more explicit, critical intent. Even in the few cases where such intent is obvious, power is being treated as firmly embedded in different types of isomorphism and thus difficult to influence unless isomorphic pressures change. A charitable reading may suggest that such embedding signifies an emphasis on systemic power that reinforces particular accounting practices. However, given the lack of attention to human agency, few insights are provided into how such embeddedness conditions the efforts of various actors to reproduce or alter power relations in organisations and institutional fields. This perpetuates a view of institutional theory as a predominantly structuralist, if not deterministic, perspective that has often been a source of criticism of research relying too heavily on notions of institutional isomorphism. It also limits our understanding of how SEA practices may be altered if they are found to be ineffectual in addressing issues of marginalisation and disenfranchisement in particular contexts.

3.3 Actor-centric approaches

Institutional research on SEA adopting a more actor-centric perspective has evolved along a number of different trajectories. Nearly half of the studies adopting such a perspective mobilise notions of institutional entrepreneurship (Caron and Turcotte Citation2009, Larrinaga et al. Citation2020, Chakhovich and Virtanen Citation2021) or strategic agency (Bebbington et al. Citation2009, Ball and Craig Citation2010, Islam and McPhail Citation2011, Smith et al. Citation2011, Perego and Kolk Citation2012, Egan Citation2014, Wijethilake et al. Citation2017, Higgins et al. Citation2018, Khan et al. Citation2020, Clementino and Perkins Citation2021, Ben-Amar et al. Citation2023) to make sense of how institutional change is initiated or how individual organisations respond to institutional pressures. In doing so, they generally recognise the criticism of earlier variants of institutional theory, focusing on institutional isomorphism, for downplaying the role of human agency in institutional processes. However, they largely fail to extend the discussion beyond this criticism and engage with more recent debates about how the agency that evolves in organisations and institutional fields needs to be conceived of as an institutionally embedded phenomenon and thus score low on the ambition to develop institutional theory conceptually. Even though they typically recognise that extant institutions often constrain the possibilities of agency and change, there is little attention to how the beliefs and values that originate in such institutions may be implicated in a complex interplay with reflexive agency and how this interplay shapes the reproduction and transformation of accounting practices (cf. Seo and Creed Citation2002, Battilana and D’Aunno Citation2009).

Similar to much SEA research exploring the influence of institutional isomorphism, this lack of deeper engagement with questions of embedded agency is perhaps due to the research topics being investigated and the methods that are being employed. The majority of the studies cited above are either cross-sectional field studies (Bebbington et al. Citation2009, Khan et al. Citation2020, Clementino and Perkins Citation2021, Ben-Amar et al. Citation2023) or based on qualitative content analyses (Caron and Turcotte Citation2009, Islam and McPhail Citation2011, Perego and Kolk Citation2012, Larrinaga et al. Citation2020) of how organisations adapt their disclosure and reporting practices to institutional pressures. But even in the few cases where there are somewhat deeper, case-study based engagements with how SEA practices are institutionalised are there any ostensible attempts to theorise notions of embedded agency due to the relatively superficial and dated engagements with debates about how human agency is possible in institutional environments (Ball and Craig Citation2010, Egan Citation2014, Wijethilake et al. Citation2017, Chakhovich and Virtanen Citation2021). Hence, the lack of attention to embedded agency is not necessarily due to the heavy focus on organisations’ disclosure and reporting practices or the choice of research methods, but can also be traced to a more general failure to keep up with key conceptual developments in institutional theory.

Yet, this tendency to ignore notions of embedded agency and how such agency is implicated in the reproduction and transformation of SEA practices is not a universal feature of research following an actor-centric approach to institutionalisation. A growing number of studies have started to take such issues seriously by advancing deeper, longitudinal analyses of the process of institutionalisation and how such processes are influenced by the beliefs and values that shape the agency exercised by key actors. Some authors have explored how such processes unfold within individual organisations (Contrafatto and Burns Citation2013, Cooper et al. Citation2014), while others have extended such analyses to the institutional field level (Archel et al. Citation2011, O’Sullivan and O’Dwyer Citation2015, Humphrey et al. Citation2017, Contrafatto et al. Citation2020, Larrinaga and Bebbington Citation2021) or advanced multi-level studies bridging these levels of analysis (Moore Citation2013). Some of these studies have also sought to extend extant conceptualisations of how institutionalisation works and thus display a high ambition to develop institutional theory conceptually. For instance, in their study of the institutionalisation of the Equator Principles as a basis for bank financing operations, O’Sullivan and O’Dwyer (Citation2015) extended emerging, issue-based conceptualisations of institutional fields with insights from the social movement organisations literature. In doing so, they demonstrate how the field formed around these principles emerged from within an established, mature field and how the embeddedness of key actors in the latter field, as well as less powerful actors who were embedded in the values associated with social movements, contributed to the shaping of the new field. Similarly, examining the emerging efforts to institutionalise integrated reporting, Humphrey et al. (Citation2017) extended extant conceptualisations of how professions shape institutional fields with the notion of boundary work to explain how various actors establish boundaries around emerging fields and imbue such fields with values in which they, themselves, are embedded.

A similar ambition to take notions of embedded agency as a basis for developing institutional theory conceptually can be found in at least parts of the growing SEA literature mobilising the notion of institutional work. For instance, in their study of how new forms of environmental accountability were institutionalised in an investment field, Clune and O’Dwyer (Citation2020) carefully outlined how the beliefs and values of key actors involved in this process shaped their institutional work while drawing on the notion of organising dissonance to enhance our understanding of how such work was implicated fostering collective action. Similarly, in examining the efforts of auditors to promote novel sustainability assurance practices, Silvola and Vinnari (Citation2021) combined insights from the institutional work and institutional logics perspectives to gain a more profound understanding of how extant institutions shape the agency exercised by different actors than has arguably been the case in much research following the former perspective. Similar concerns with embedded agency can be found in two other studies of the institutional work involved in the establishment of SEA practices, although these studies do not extend or refine institutional theory in any significant ways and thus display a moderate ambition to develop institutional theory conceptually (Gibassier Citation2017, Farooq and de Villiers Citation2019a). However, there are also a number of studies where the concerns with embedded agency are much less salient (Higgins et al. Citation2014, Farooq and de Villiers Citation2019b, Citation2020, Gibassier et al. Citation2020). Some of these studies go to some length in unpacking the notion of institutional work conceptually and offer detailed empirical analyses of how such work unfolds but pay little attention to how the institutionalised beliefs and values of different actors shape their efforts to influence accounting practices (Farooq and de Villiers Citation2019b, Citation2020, Gibassier et al. Citation2020). Hence, similar to Modell (Citation2022a), it is fair to conclude that far from all SEA research mobilising the institutional work perspective has been entirely faithful to its core premise that human agency is constrained as well as enabled by the institutions in which actors are embedded.

Taken together, the above discussion shows that even though some progress has been made in examining the agency involved in the institutionalisation of SEA practices as an institutionally embedded phenomenon, this is not the case in the majority of the studies following an actor-centric approach. As such, most of this research scores low on the ambition to develop institutional theory conceptually. The limited attention to embedded agency also has important implications for how the exercise of power has been conceptualised and how such conceptualisations have been translated into attempts to critique SEA practices. Starting with the studies exploring the influence of institutional entrepreneurship and strategic agency, most of these studies discuss how such forms of agency entail the exercise of power and the policy implications that follow from this (Caron and Turcotte Citation2009, Islam and McPhail Citation2011, Smith et al. Citation2011, Perego and Kolk Citation2012, Wijethilake et al. Citation2017, Khan et al. Citation2020, Larringa et al. Citation2020, Chakhovich and Virtanen Citation2021, Clementino and Perkins Citation2021). While this draws attention to how power relations might change as SEA practices are institutionalised, the emphasis on intentional agency that is inherent in these approaches leads to a relatively one-sided emphasis on episodic power. In some cases, this results in rather anodyne accounts of power that valorise the role of management. For instance, in their study of how institutional pressures for sustainability affected the management control practices of an apparel manufacturer in Sri Lanka, Wijethilake et al. (Citation2017) advanced a highly managerialist account of empowerment and emphasised that this may help organisations to improve performance by going beyond such pressures while paying little attention to the effects on a wider range of constituencies. But for the most part, authors are more circumspect and raise concerns about how power can be a source of managerial or professional capture of the SEA agenda at the expense of broader notions of social and economic equity and sustainability (Caron and Turcotte Citation2009, Smith et al. Citation2011, Perego and Kolk Citation2012, Khan et al. Citation2020, Larrinaga et al. Citation2020). As such, they can be said to be imbued with at least a moderate ambition to develop research in a critical direction. In the case of Khan et al. (Citation2020), there is even an explicit attempt to make institutional theory critical. Drawing attention to how conflicting institutional demands enable banks to use corporate social responsibility funding in ways that favour their interests rather than those of marginalised constituencies, they critiqued extant notions of strategic agency in institutional theory for ignoring such implications.

As the above discussion makes plain, adopting an actor-centric approach emphasising notions of episodic power does not necessarily mean jettisoning the ambition to advance institutional research on SEA in a critical direction. However, for this to be combined with a more pronounced ambition to develop institutional theory conceptually and nuance accounts of how power is exercised, there needs to be greater attention to the institutional embeddedness that underpins systemic forms of power. Such nuancing of the analysis of power is evident in a small number of actor-centric studies that have sought to advance research in a critical direction (Contrafatto and Burns Citation2013, Cooper et al. Citation2014, O’Sullivan and O’Dwyer Citation2015, Gibassier Citation2017, Clune and O’Dwyer Citation2020), although it is still rare for such research to feature explicit ambitions to make institutional theory critical (Archel et al. Citation2011, Contrafatto et al. Citation2020). The most explicit attempt to examine the interplay between episodic and systemic power in a concerted effort to make institutional theory critical can be found in Contrafatto et al. (Citation2020). Mobilising Lawrence’s (Citation2008) framework, they examined the institutionalisation of corporate social responsibility policies in the European Union. In doing so, they showed how the discourse that emerged from these initiatives gradually caused particular conceptions of social responsibility to be institutionalised and how this created a source of systemic power that conditioned the ability of various actors who sought to affect policy development to exercise episodic power through lobbying and other influence activities. These observations underline the need to conceive of the exercise of episodic power as implicated in a complex interplay with the institutions in which actors are embedded and how this interplay affects the mobilisation of collective action in organisations and institutional fields. Similarly, combining institutional theory with a Bourdieusian perspective to make the former critical, Archel et al. (Citation2011) showed how a range of actors involved in the institutionalisation of corporate social responsibility in Spain were co-opted into a discourse that was infused with beliefs and values that served dominant constituencies. This embedding of agents in dominant discourses at an early stage of the process of institutionalisation shaped the power relations that conditioned stakeholder consultations and ultimately reinforced the marginalisation of broader concerns with economic and social equity and sustainability. Reflecting on the policy implications of these observations, Archel et al. (Citation2011) questioned the efficacy of regulations building on such consultations and called for more radical forms of resistance by marginalised groups as a way of broadening the SEA agenda while recognising that such attempts to exercise episodic power will always be conditioned by the institutions in which actors are embedded.

To summarise, even though some progress has been made in taking questions of embedded agency into account in institutional research on SEA and combining this with efforts to develop research in a critical direction, this has not been the case in the majority of the studies following an actor-centric approach. In comparison with research on institutional isomorphism, more attention is certainly being paid to how power relations might change in organisations and institutional fields. However, for the most part, this has been accompanied by a relatively one-sided emphasis on episodic power. Studies combining a focus on episodic power with greater emphasis on institutional embeddedness as a source of systemic power are rarer and have seldom taken the form of explicit attempts to make institutional theory critical. Hence, there is little, if any, evidence of institutional research on SEA following an actor-centric approach scoring high on the ambition to develop institutional theory conceptually as well as the ambition to advance research in a critical direction.

3.4 Institutional logics