Abstract

Background: Colorectal cancer in pregnancy is rare, with an incidence of 0.8 per 100,000 pregnancies. Advanced disease (stage III or IV) is diagnosed more frequently in pregnant patients. We aimed to review all cases of colorectal cancer in pregnancy from the International Network on Cancer, Infertility and Pregnancy database in order to learn more about this rare disease and improve its management.

Methods: Data on the demographic features, symptoms, histopathology, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions and outcomes (obstetric, neonatal and maternal) were analysed.

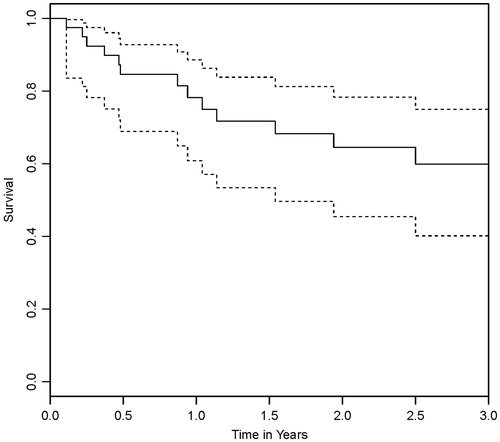

Results: Twenty-seven colon and 14 rectal cancer cases were identified. Advanced disease was present in 30 patients (73.2%). During pregnancy, 21 patients (51.2%) received surgery and 12 patients (29.3%) received chemotherapy. Thirty-three patients (80.5%) delivered live babies: 21 by caesarean section and 12 vaginally. Prematurity rate was high (78.8%). Eight babies were small for gestational age (27.6%). Three patients (10.7%) developed recurrence of disease. Overall 2-year survival was 64.4%.

Conclusion: Despite a more frequent presentation with advanced disease, colorectal cancer has a similar prognosis in pregnancy when compared with the general population. Diagnostic interventions and treatment should not be delayed due to the pregnancy but a balance between maternal and foetal wellbeing must always be kept in mind.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00330447.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) in pregnancy is rare, with an incidence of 0.8 per 100,000 pregnancies [Citation1]. The diagnostic and therapeutic management of pregnant patients with CRC is especially difficult because it involves two individuals, the mother and the foetus. Locally advanced or metastatic CRC is diagnosed more often in pregnant than in non-pregnant patients because the presenting signs and symptoms of CRC are easily attributable to pregnancy [Citation2]. Presentation with advanced CRC during pregnancy is thought to be a result of delayed diagnosis [Citation3]. In this study, we analyse all the cases of CRC during pregnancy from the International Network on Cancer, Infertility and Pregnancy (INCIP) database [Citation4] with specific focus on the treatment modalities given during pregnancy and the obstetric, neonatal and maternal outcomes. Recommendations for clinical practice are given in order to improve the awareness and management of CRC during pregnancy.

Materials and methods

For this international observational cohort study, we identified all patients diagnosed with CRC during pregnancy from the INCIP registration study, registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00330447). Patients diagnosed with a recurrence of CRC were excluded. Data on demographic features, symptoms, histopathological characteristics, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions and outcomes (obstetric, neonatal and maternal) were collected.

The INCIP started in 2005 and collects oncological, obstetric and perinatal data related to the pregnant patients diagnosed with all types of cancer. At the time of case inclusion, it contains information reported by 70 doctors from 62 medical centres in 25 countries. Reporting of patients occurs on a voluntary basis by the doctors affiliated to the INCIP, all of whom work in the specialized hospitals where patients with cancer during pregnancy are treated. For more information see www.cancerinpregnancy.org.

Birthweight percentiles were calculated according to the percentile calculator from www.gestation.net (v6·7·5·7(NL), 2014). The parameters used were gestational age (GA) at delivery, birth weight, gender of offspring and weight, height, ethnicity and parity of the mother. Birth weight below the 10th percentile was considered as ‘small for gestational age’ (SGA). The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate the survival rates (one and 2-year overall and stage specific survival).

Results

Twenty-seven patients diagnosed with colon cancer and 14 with rectal cancer were included. Three patients diagnosed with a recurrence of colon cancer during pregnancy were excluded. Patients were diagnosed between 1988 and 2016 and originated from eight different countries: USA (n = 13), Netherlands (n = 6), Belgium (n = 5), France (n = 4), Italy (n = 6), Czech Republic (n = 3), Denmark (n = 2) and Poland (n = 2).

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in . One patient had Crohn’s disease, one Lynch syndrome and 12 had a positive family history for CRC. Other reported risk factors included smoking (n = 9) and obesity (n = 3).

Table 1. Patient characteristics (n = 41).

Presentation and diagnosis

In ten patients the diagnosis of CRC was made during acute surgery. Four patients underwent surgery for acute bowel obstruction, three for bowel perforation, two for suspicion of ovarian torsion and one for acute appendicitis.

Thirty-one patients presented non-acutely. Their main presenting symptoms were rectal bleeding (n = 19), abdominal pain (n = 7), a change in bowel habits (n = 2), weight loss (n = 1), abdominal mass (n = 1) and right shoulder pain (n = 1). The diagnosis of CRC was made by endoscopy with biopsy performed during pregnancy in 27 of these patients. Four patients did not undergo endoscopy during pregnancy; the diagnosis was made by MRI in three patients and by CT in one patient. See .

Table 2. Clinical presentation and diagnosis (n = 41).

Tumour characteristics

See for tumour characteristics. Six tumours were located in the right colon, 21 in the left colon and 14 in the rectum. Staging was reported in all patients; thirty (73.2%) had advanced disease (stage III and IV). Tumour histology was reported in 39 patients; three patients (7.7%) had adverse histological subtypes. Tumour grade was known in 25 patients; 8 (32.0%) were poorly differentiated.

Table 3. Tumour characteristics (n = 41).

Treatment

Detailed treatment characteristics are described in . Twenty-one patients (51.2%) underwent surgery during pregnancy. Emergency surgeries consisted of four right hemicolectomies, two left hemicolectomies, one relieving stoma, one oophorectomy, one diagnostic laparoscopy and one appendectomy. The appendectomy revealed a caecal adenocarcinoma and the oophorectomy revealed metastasis of a colorectal carcinoma. These two patients further underwent an elective right hemicolectomy and sigmoid resection during pregnancy, respectively. An additional eleven patients underwent elective surgery during pregnancy. These procedures included left hemicolectomy (n = 5), sigmoid resection (n = 3), transanal tumour resection (n = 2) and low anterior resection (LAR) (n = 1).

Table 4. Summary of diagnosis, treatment, obstetric, neonatal and maternal outcomes of the colon cancer patients with acute clinical presentation.

Table 5. Summary of diagnosis, treatment, obstetric, neonatal and maternal outcomes of the colon cancer patients with non-acute clinical presentation (n = 17).

Table 6. Summary of diagnosis, treatment, obstetric, neonatal and maternal outcomes of the rectal cancer patients (n = 14).

Twelve patients (29.3%) received chemotherapy during pregnancy; neoadjuvant (n = 4), adjuvant (n = 6) and palliative (n = 2). Chemotherapy was administered in the second (n = 7) and third (n = 5) trimester. All patients received multiple chemotherapy cycles during pregnancy (range 2–9).

None of the patients were treated with radiotherapy during pregnancy.

Obstetric and neonatal outcome

Thirty-three patients (80.5%) delivered live babies: 21 by caesarean section and 12 vaginally. Five patients terminated the pregnancy and two miscarried. The pregnancy outcome for one patient was unknown. Twenty-six babies (78.8%) were born preterm, in all cases these births were induces (8 induced vaginal deliveries and 18 caesarean sections). Median GA at delivery was 35 weeks (range 27–40). Median birth weight was 2330 grams (range 900–3462). Birth weight percentile was calculated in 29 patients; eight babies (27.6%) were SGA. Babies exposed to antenatal chemotherapy tend to be more likely to be SGA than those who were not (4/12 (33.3%) vs 4/17 (23.5%). All 33 babies had APGAR scores of 7 or more at 5 minutes. Twenty-one babies (63.6%) were admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit. One baby, who was exposed to antenatal surgery and chemotherapy, had a leg length discrepancy. No other congenital malformations were reported.

Maternal outcome

The median follow-up period was 561 days (range 12–4152), nine patients were lost to follow up by one year from diagnosis and eleven patients were lost to follow up by 2 years. One-year overall survival rate was 78.1% and two-year survival rate was 64.4% (). In total, 13 maternal deaths were reported, 12 occurring in patients with stage IV disease within 2 years after diagnosis and one in a patient with stage III disease in the third year after diagnosis. Patients with stage IV disease had a one-year survival rate of 48.6% and a two-year survival rate of 20.8%. No deaths occurred in patients with localized disease.

Discussion

Epidemiology

Only 2–8% of CRC patients are under 40 years old, making CRC rare in pregnancy. A population study from New South Wales, Australia, reports 10 cases of CRC during pregnancy from a total of 1,309,501 pregnancies recorded between 1994 and 2007, corresponding to an incidence of 0.8 per 100,000 pregnancies [Citation1]. Delayed childbearing and an increasing frequency of CRC in younger patients may increase CRC incidence in pregnancy [Citation5].

Up to 20–30% cases of CRC have an identifiable predisposing factor [Citation6]. These factors can be a family history of CRC, cancer-predisposing genetic syndromes and inflammatory bowel disease. The presence of these risk factors was slightly higher in our patient cohort than the general population as a total of fourteen patients (34.1%) had predisposing factors.

Bernstein’s study from 1993 stated that at the time of publication there had been 205 cases of CRC reported in the literature, the majority of which (80%) were located in the rectum [Citation3]. We observed rectal tumours in 34.1% of our pregnant patients, a finding more consistent with the general population (30%) [Citation7].

Presentation and diagnosis

CRC symptoms such as abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, constipation, nausea and vomiting are easily attributed to the physiological changes of pregnancy. This leads to delayed diagnosis and presentation with advanced disease. In Bernstein’s study of CRC during pregnancy, presentation with advanced disease (stage III and IV) was found in 59% of cases [Citation3]. Advanced disease at presentation has also been reported in several case reports of CRC during pregnancy [Citation8–10]. Similarly, in our study the majority of patients (73.2%) presented with advanced disease.

Diagnosis of CRC during pregnancy can be complicated by the presumed risks of imaging modalities, and hesitancy to perform such imaging during pregnancy. Endoscopy is the principal method of CRC diagnosis. Its use in pregnancy is believed to carry only a small risk [Citation11]. When staging of CRC is performed during pregnancy the maternal benefit should be weighed against the foetal risk and non-ionizing methods should be prioritized whenever possible. Abdominal ultrasound can detect liver metastases larger than one cm but has a moderate sensitivity of 50–76%, often needing additional investigations [Citation12]. Endoscopic rectal ultrasound (ERUS) can be used for locoregional staging of rectal cancer, detecting T1 tumours more accurately than CT or MRI, which then can potentially be resected with transanal endoscopic microsurgery [Citation13]. This advantage is limited in pregnant patients because only a small percentage present with T1 tumours. ERUS can also detect bulky tumours of the anterior rectal wall, which can obstruct the vaginal canal, complicating delivery. While CT is the standard staging method in non-pregnant CRC patients, in pregnancy MRI is preferred as it does not expose the foetus to ionizing radiation and has a similar accuracy to CT in the diagnosis of CRC [Citation14]. Recent guidelines on MRI, during pregnancy, state that abdominopelvic MRI can be safely used, regardless of GA [Citation15]. The use of gadolinium is discouraged during pregnancy [Citation16]. Ionizing techniques are relatively safe to use in pregnancy providing the cumulative foetal radiation dose does not exceed 100 miligray (mGy). Thoracic CT has the highest sensitivity in detecting pulmonary metastases and exposes the foetus to low doses of radiation (0.002–0.2 mGy) [Citation17]. Abdominal CT gives higher foetal doses of radiation (4–60 mGy) and should be avoided. Serum levels of CEA are not elevated by pregnancy and may be used to monitor response to therapy and to detect tumour recurrence [Citation18].

Treatment

The management of CRC during pregnancy depends on the stage and location of the cancer, elective versus emergency presentation, GA and the patients’ wishes.

Surgical treatment

The timing of surgery should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team to optimize the maternal and foetal outcomes. In order to prevent disease progression, surgery should be performed without delay. This means that in case of diagnosis early in pregnancy, surgery should be performed during pregnancy, preferably before the 20th week of gestation when complete resection is still feasible, since the uterus is still relatively small [Citation19]. Advances in surgical techniques and anaesthesia have dramatically improved foetal outcome, following non-obstetric surgical interventions in pregnancy [Citation20]. In our study the miscarriage rate for patients undergoing surgery within the first twenty weeks of pregnancy was 14.3%, which is similar to the miscarriage rate of the general population (15%), indicating that operating before the 20th week is relatively safe [Citation21]. Radical surgery after the 20th week of gestation is challenging in colon cancer and almost impossible in rectal cancer due to the enlarged uterus, and postpartum surgery is then preferred. After vaginal delivery, surgery is typically performed several weeks later. If a CS is planned, the decision whether to resect the tumour during the same procedure or to wait till the delivery depends on several factors. Colon cancers can usually be resected during the same operation as the CS. However, rectal cancers are more complicated. The enlarged uterus may block access to the rectum, necessitating a hysterectomy. Waiting several weeks after delivery allows the uterus to involute, which improves access to the rectum, making hysterectomy unnecessary. Furthermore, it gives time for the pelvic vessels to decongest, decreasing the risk of bleeding [Citation3,Citation19]. Acute CRC complications require emergency laparotomy at any GA. Chen et al. report bowel perforation and obstruction in 14% of CRC cases in the general population [Citation22]. We found these acute complications in 17% of our patients, correlating with the larger proportion of advanced CRC in our study.

Chemotherapy

Multi-agent chemotherapy in the first trimester is highly teratogenic, with a 15–25% miscarriage and malformation rate [Citation23]. Its use in the first trimester is only warranted in metastatic high burden disease, when the mother cannot carry the foetus to a viable GA. In the second and third trimesters, chemotherapy is safer, although it is associated with an increased incidence of SGA, especially for platinum-based chemotherapy [Citation24]. Chemotherapy must be stopped two to three weeks before delivery to decrease the risk of myelosuppression of the foetus and mother and to give time for the placenta to clear the drugs from the foetal circulation. CRC chemotherapy is 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and oxaliplatin based. 5-FU based regimens are standard for pregnant patients with breast cancer and are well studied [Citation25]. Less is known about these regimens in pregnant CRC patients. The few case reports on 5-FU and oxaliplatin in pregnant CRC patients suggests they are relatively safe [Citation9,Citation10], but a recent study found an association between platinum-based chemotherapy and SGA [Citation24]. In our study, 12 patients (eight colon cancer, four rectal cancer) received 5-FU-based chemotherapy in the second and third trimester, and five of these regimens given during pregnancy contained oxaliplatin. However, only one child born from these 5 patients was SGA. It is possible that five patients are too little to observe such an impact on the foetal growth, or that foetal growth did decline during pregnancy but did not drop below the 10th percentile and was therefore not identified as SGA in this cohort. Due to the possible negative effect of antenatal chemotherapy on foetal growth, it is important to strictly evaluate foetal wellbeing, including growth, in these patients. One baby exposed to chemotherapy had a leg length discrepancy. The mother of this baby was 39 years of age, had Sjögren syndrome and was multiparous with complications in her previous pregnancies (HELLP syndrome in one case and shoulder dystocia in another case). In accordance with the literature, pregnant patients with Sjögren syndrome are likely to experience more complications during pregnancy (an increased rate of miscarriage and stillbirths, intrauterine growth restriction, prematurity, neonatal lupus and congenital heart block) than patients without an autoimmune disease [Citation26]. Furthermore, this patient underwent LAR in the first trimester. Therefore, it is not clear what role, if any, chemotherapy played in the development of the congenital malformation.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is indicated preoperatively in locally advanced rectal cancer (T3/4N+). If indicated in pregnant CRC patients, it should be applied postpartum because the radiation doses are lethal to the foetus [Citation27]. A further consideration is that radiotherapy of the lesser pelvis may cause ovarian failure, leading to infertility in these young women [Citation28].

Maternal and neonatal outcome

The overall 1-year survival of pregnant patients with CRC was 78.1%, for stage IV 48.6% and for all other stages 100%. For a comparison, we looked at age standardized survival data for female colorectal cancer patients aged 15–99 in the UK from the year 2014 [Citation29]. These patients had overall one-year survival of 72.6% and stage specific one-year survival rates of 35.2%, 84.8%, 91.2% and 98.3% for stages IV, III, II and I, respectively. We observed similar stage-by-stage survival, and, despite the high incidence of advanced disease (73.2%, compared with 52–56% in the general population), our cohort had a similar overall survival to the females in the general population. According to the literature, CRC during pregnancy has a poor prognosis. However, the literature consists only of case reports and one case series from 1993 [Citation3]. The better prognosis in our study may result from improvements in treatment and a decreased hesitancy to perform diagnostic and therapeutic intervention during pregnancy.

Besides high numbers of SGA in our population, compared to the healthy pregnant population, we observed high numbers of iatrogenic preterm delivery (78.8%) and CS (63.3%). The majority of iatrogenic preterm deliveries were induced to apply treatment as soon as possible without the risk of harming the foetus. Data from a multicentre international study show that premature birth is more harmful to psychomotor development than in utero chemotherapy exposure [Citation30]. We believe that certain situations demand premature delivery in order to start postpartum therapy such as radiotherapy, or surgery that could not be performed during pregnancy. However, inducing delivery to start chemotherapy for fear of adverse fetal effects may not be in the best interest of the unborn child, especially when 5-FU based regimens are of first choice.

Evidence based guidelines on CRC during pregnancy are lacking. This study is one of the largest series that describes the management and outcome for CRC during pregnancy and adds important information for this rare patient population. As a result of the rarity of CRC during pregnancy, our patient sample size is relatively small. A limitation of our study is that registration of these cases is voluntarily based and we cannot estimate the completeness of the database and it is therefore likely that not all cases of CRC during pregnancy are included in this analysis. Since all hospitals included all their cases, and not just the advanced stage of disease cases, we do not expect a selection bias on stage of disease at diagnosis.

In conclusion, CRC during pregnancy presents with advanced disease more frequently than in the general population. This may be due to negligence of CRC symptoms such as rectal bleeding and abdominal pain, which can be mistaken as the symptoms of pregnancy. Pregnant patients with these symptoms should be investigated completely and without delay. Diagnostic and staging methods are generally safe in pregnancy and should not be delayed. Surgery can be performed without harming the pregnancy, with respect to the stage of the disease and the timing of the surgery. Chemotherapy in second and third trimester is relatively safe but increases the risk of SGA. Chemotherapy must be stopped two or three weeks before delivery or when foetal growth is hampered. Induced preterm delivery should be avoided, as it seems to be more harmful to the foetus than applying chemotherapy in the third trimester. CRC during pregnancy should be managed in tertiary hospitals by multidisciplinary teams consisting of obstetricians, gynaecologists, neonatologists, surgeons, oncologists, gastroenterologists and radiologists.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge all members of the writing committee on this manuscript; Kristel Van Calsteren M.D., Ph.D.; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium and Department of Reproduction and Regeneration, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium. Karina Dahl Steffensen M.D., Ph.D.; Department of Clinical Oncology, Vejle Hospital, Vejle, Denmark and Institute of Regional Health Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense C, Denmark. Charles Honoré M.D. and Alexander Mare M.D.; Department of Surgery, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus, 114, rue Édouard Vaillant, 94805 Villejuif Cedex, Université Paris Sud, France. Mina Mhallem Gziri M.D., Ph.D.; Department of Obstetrics, Cliniques Universitaires St. Luc, Brussels, Belgium. Anna Skrzypczyk M.D., Ph.D.; Department of Breast Cancer and Reconstructive Surgery, Maria Sklodowska-Curie Memorial Cancer Centre and Institute of Oncology, Warsaw, Poland. Ingrid A. Boere M.D., Ph.D.; Department of Medical Oncology, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Giovanna Scarfone M.D. Ph.D.; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Fondazione IRCCS CA' GRANDA, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Ostetricia e Ginecologia I, Clinica Mangiagalli, Università di Milano, Italy. The authors gratefully acknowledge Adam Whitley, MD for reviewing the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

Frédéric Amant, PhD, MD, is senior researcher for the Research Fund Flanders (F.W.O.). The authors have no other conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lee YY, Roberts CL, Dobbins T, et al. Incidence and outcomes of pregnancy-associated cancer in Australia, 1994-2008: a population-based linkage study. BJOG. 2012; 119:1572–1582.

- Cappell MS. Colon cancer during pregnancy. The gastroenterologist's perspective. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1998; 27:225–256.

- Bernstein MA, Madoff RD, Caushaj PF. Colon and rectal cancer in pregnancy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993; 36:172–178.

- INCIP members. International Network on Cancer, Infertility and Pregnancy n.d. [Internet]. Available from: www.cancerinpregnancy.org [cited 2016 Jun 10].

- O'Connell JB, Maggard MA, Liu JH, et al. Rates of colon and rectal cancers are increasing in young adults. Am Surg. 2003; 69:866–872.

- Jasperson KW, Tuohy TM, Neklason DW, et al. Hereditary and familial colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010; 138:2044–2058.

- Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975–2010. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:17–22.

- Toosi M, Moaddabshoar L, Malek-Hosseini SA, et al. Rectal cancer in pregnancy: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2014; 26:175–179.

- Jeppesen JB, Østerlind K. Successful twin pregnancy outcome after in utero exposure to FOLFOX for metastatic colon cancer: A case report and review of the literature. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2011; 10:348–352.

- Makoshi Z, Perrott C, Al-Khatani K, et al. Chemotherapeutic treatment of colorectal cancer in pregnancy: case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015; 9:140

- Cappell MS, Colon VJ, Sidhom OA. A study at 10 medical centers of the safety and efficacy of 48 flexible sigmoidoscopies and 8 colonoscopies during pregnancy with follow-up of fetal outcome and with comparison to control groups. Digest Dis Sci. 1996; 41:2353–2361.

- Glover C, Douse P, Kane P, et al. Accuracy of investigations for asymptomatic colorectal liver metastases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002; 45:476–484.

- Siddiqui A. a, Fayiga Y, Huerta S. The role of endoscopic ultrasound in the evaluation of rectal cancer. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2006; 3:36

- Hosch WP, Schmidt SM, Plaza S, et al. Comparison of CT during arterial portography and MR during arterial portography in the detection of liver metastases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006; 186:1502–1511.

- Kanal E, Barkovich AJ, Bell C, et al. ACR guidance document on MR safe practices: 2013. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013; 37:501–530.

- Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Bharatha A, et al. Chen MM, Coakley FV, Kaimal A, et al. Association between MRI exposure during pregnancy and Fetal and Childhood Outcomes. JAMA. 2016; 316:952–961.

- de Haan J, Vandecaveye V, Han SN, et al. Difficulties with diagnosis of malignancies in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016; 33:19–32.

- Sarandakou A, Protonotariou E, Rizos D. Tumor markers in biological fluids associated with pregnancy. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2007; 44:151–178.

- Nesbitt JC, Moise KJ, Sawyers JL. Colorectal carcinoma in pregnancy. Arch Surg. 1985; 120:636–640.

- Cohen-Kerem R, Railton C, Oren D, et al. Pregnancy outcome following non-obstetric surgical intervention. Am J Surg. 2005; 190:467–473.

- Regan L, Rai R. Epidemiology and the medical causes of miscarriage. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2000; 14:839–854.

- Chen HS, Sheen-Chen SM. Obstruction and perforation in colorectal adenocarcinoma: an analysis of prognosis and current trends. Surgery. 2000; 127:370–376.

- Pentheroudakis G, Orecchia R, Hoekstra HJ, et al. Cancer, fertility and pregnancy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010; 21:v266–v273.

- de Haan J, Verheecke M, Van Calsteren K, et al. Oncological management and obstetric and neonatal outcomes for women diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy: a 20-year international cohort study of 1170 patients. Lancet Oncol. 2018; 19:337–346.

- Cardonick E, Iacobucci A. Use of chemotherapy during human pregnancy. Lancet Oncol. 2004; 5:283–291.

- Julkunen H, Kaaja R, Kurki P, et al. Fetal outcome in women with primary Sjögren's syndrome. A retrospective case-control study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1995; 13:65–71.

- Martin DD. Review of radiation therapy in the pregnant cancer patient. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 54:591–601.

- Meirow D, Nugent D. The effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy on female reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2001; 7:535–543.

- Office for National Statistics [Internet], Cancer survival by stage at diagnosis for England (experimental statistics): Adults diagnosed 2012, 2013 and 2014 and followed up to 2015 [cited 2016 Jun 10]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/cancersurvivalbystageatdiagnosisforenglandexperimentalstatistics/adultsdiagnosed20122013and2014andfollowedu pto2015

- Amant F, Vandenbroucke T, Verheecke M, et al. Pediatric outcome after maternal cancer diagnosed during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:1824–1834.