Abstract

A 52-year-old woman, who is a carrier of MLH-1 mutation (HNPCC-type Lynch syndrome) with a history of colon adenocarcinoma, was diagnosed with a 26 mm lobulated contrast-capturing mass located caudally of the pancreas tail, anteromedial of the spleen and medial of the splenic colon angle. She underwent an exploratory laparotomy with resection of the tumor. Initially, this mass was presumed to be metastasis in a patient with a history of colon adenocarcinoma. However, after further histopathological and immunohistochemical examination, the mass appeared to be a rare PEComa. Only a few cases of a PEComa in this retroperitoneal perirenal location have been described.

Introduction

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) are mesenchymal neoplasms composed of histologically and immunohistochemically distinctive perivascular epithelioid cells as described by the World Health Organization (WHO) [Citation1]. It is a family of tumors that occurs most commonly in females and can be found in many locations. The tumors in the PEComa family include angiomyolipoma (AML), lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), clear-cell sugar tumor (CCST) of the lung, clear-cell myomelanocytic tumor of ligamentum teres/falciform, abdominopelvic sarcoma of perivascular epithelial cells and primary extrapulmonary sugar tumor [Citation2]. The latter are unusual clear tumors of organs other than the lung, such as the pancreas, rectum, uterus, vulva, heart and orbit. PEComas are rare tumors, with AML as the most common type. Only 160 cases of AML PEComa have been described [Citation2]. Only four cases of PEComas with perirenal manifestation have been reported [Citation1].

The clinical presentation and radiographic appearance of these tumors are unspecific and can often mimic that of carcinomas, smooth muscle tumors, adipocytic tumors, clear cell sarcomas, melanomas and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). Reported cases are scares, however, the lesions generally seem to be solid, possibly centrally necrotic, and demonstrate contrast enhancement. The differential diagnosis depends upon the location of the mass and a definitive diagnosis is reached by the immunohistological investigation.

Histologically, the origin of these tumors is uncertain and the histological pattern is not well defined. Perivascular epithelioid cells normally have no counterpart in normal tissue and the name refers to the characteristics of the tumor when examined under the microscope. The tumor usually consists of cells with a clear/granular cytoplasm and a central round nucleus without prominent nucleoli. On an immunohistochemical basis, the PECs characteristically stain for melanocytic markers (HMB-45, Melan A (Mart 1), Mitf) and myogenic markers (actin, myosin, calponin).

Assessing the malignant potential of these PEComas remains challenging, as the histological characteristics of a malignant PEComa are not well defined. Some PEComas exhibit more malignant characteristics, while others may be regarded as having uncertain malignant potential. Whether or not a PEComa is malignant, is often based on the presence or absence of metastatic spread and malignant PEComas usually display a far more aggressive clinical course than benign variants. They appear to arise most commonly at visceral, retroperitoneal and abdominopelvic sites. The PEComa with pancreatic manifestation is exceedingly rare and to date, only a few cases have been described.

Case report

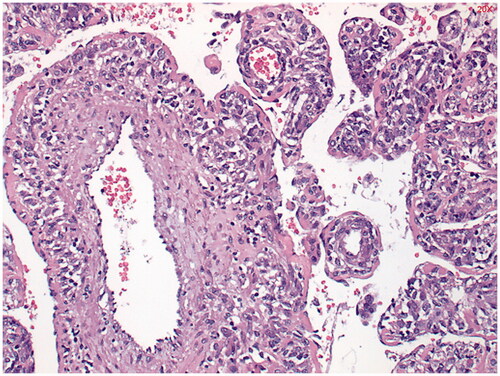

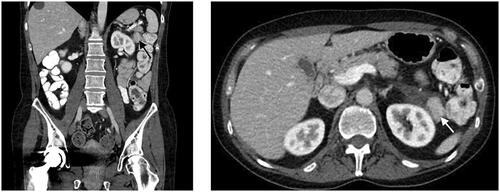

A 52-year-old Caucasian woman with a history of a right hemicolectomy in the context of a colon adenocarcinoma pT1N0M0 in 2007, underwent a follow-up CT scan, which showed a moderately large (2.6 cm), lobulated contrast-capturing nodule or mass at the left hypochondrium located caudally of the pancreas tail, anteromedial of the spleen and medial of the splenic colon angle. The mass was partially surrounded by hypodense fluid infiltration asymmetrically medial expanding peripancreatic caudally of pancreas tail and pararenal and perirenal against the upper-middle pole of the left kidney. This mass was not visible on a previous CT scan from 10 years before. Taking the oncological history into account, metastatic pathology could not be excluded. The CT scan also captured multiple smaller biliary liver cysts spread in the left and right lobe, increased in size and number compared to the previous CT scan ().

Figure 1. CT scan reveals a lobulated, contrast capturing mass, approximately 2.6 cm, as indicated by the arrow.

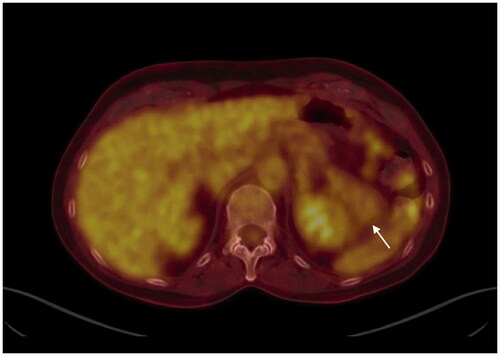

The CEA level was normal (2.7 µg/L). An MRI scan was executed and showed a lesion that is not suggestive of colon carcinoma metastasis. Additionally, a PET-CT showed the mass to be a partially cystic, partially non-hypermetabolic solid tissue, which argues against a locoregional recurrence of colon carcinoma ().

Figure 2. PET-CT shows a partly cystic partly solid tissue non-hypermetabolic mass located in the left hypochondrium, as indicated by the arrow.

After all investigations, the exact nature of the lesion remains unclear. The case was discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting and, given the oncological history and the burden of regular follow-up, it was decided to perform an excisional biopsy.

Approximately 2 months following the incidental finding of this tumor, she underwent laparoscopic resection of the mass caudally of the spleen and pancreas. The mass was adherent to the kidney, requiring the partial resection of the left kidney capsule. The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the 3rd postoperative day.

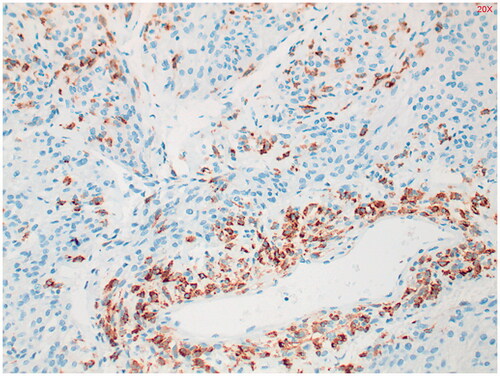

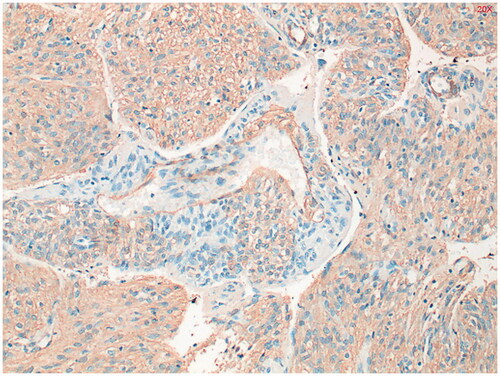

Histologically, the tumor was composed of spindle cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, hemangiopericytoma-like vascular structures and fine branching vascular lumens, suitable for a PEComa. (). The tumor involved the excision margin and resection was therefore microscopically incomplete.

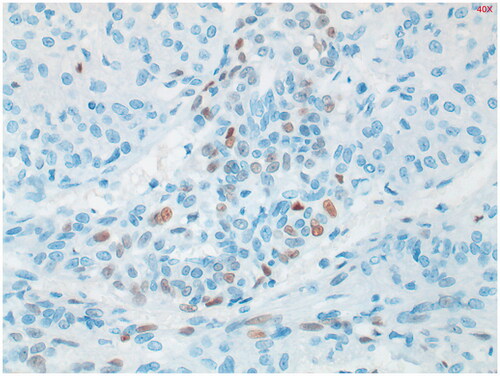

Immunohistochemical study shows staining of the tumor with alfa-SMA (smooth muscle actin) () and in the periphery, some staining with HMB-45 was seen (). Estrogen receptor (ER) staining shows limited zones with some nuclear staining (). Keratin markers, CD34, S100 and desmin were negative in the tumor cells. This presentation fits best with a PEComa. Only a single mitosis figure was found and no pronounced signs of malignancy were seen. The primary location remains unclear. Further immunohistochemical study was performed. EMA, CD117 and MelanA were negative, which argues against both a PEComa and a GIST. Provisionally, this appeared to be a fairly benign-looking soft tissue tumor, but next generation sequencing (NGS) followed to exclude a malignant tumor such as an (epithelioid) GIST.

Figure 4. Alfa-smooth muscle actin (alfa-SMA) staining shows diffuse, moderately intense staining throughout the tumor. Positive in 80% of PEComa’s.

Figure 6. Estrogen receptor (ER) staining shows limited zones with some nuclear staining. Positive in 27% of PEComa’s.

NGS mutation analysis was carried out for the detection of variants in 34 clinically relevant genes in solid tumors using the Oncomine Focus Assay. No mutation was detected in KIT or PDGFRA by the test. Samples without mutations in one of these genes generally do not respond to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib. No mutation was detected in BRAF either. Thereby, the diagnosis of a PEComa in a fairly unusual location was confirmed.

Due to the histologically fairly benign characteristics, no adjuvant therapy was given and the patient is seen in follow-up on a regular basis.

Discussion

PEComas are a family of extremely rare mesenchymal tumors composed of histologically and immunohistochemically distinctive perivascular epithelioid cells. They are mostly benign and have been described in various anatomic locations of the human body.

In the present case a retroperitoneal, perirenal mass was found during a routine follow-up CT scan of the abdomen. Initially, this mass was presumed to be metastasis in a patient who is a carrier of MLH-1 mutation (HNPCC-type Lynch syndrome) with a history of colon adenocarcinoma. However, the mass appeared to be a rare perirenal PEComa. PEComas are usually not diagnosed in a preoperative setting, because imaging findings are nonspecific and the diagnosis of PEComa is based on histological examinations of cells and immunohistochemical markers after surgical removal of the tumor.

While the majority of all PEComas have benign characteristics, these tumors have variable malignant potentials and malignant tumors have occasionally been documented [Citation3]. It remains a challenge to distinguish PEComas of benign potential from those of malignant potential and from other soft tissue malignancy.

The likeliness of malignant behavior can be estimated by means of several characteristics including older age, larger tumor size, a higher percentage of epithelioid component, severe atypia, higher percentage of atypical cells, higher mitotic count, atypical mitotic figures, necrosis, lymphovascular invasion and renal vein invasion [Citation4].

In our case, the pathological results were analyzed by more than one center to confirm diagnosis and there were no overt features of malignancy.

Treatment of PEComas usually includes surgical excision of the mass. As there is not enough literature and therefore no evidence-based treatment of PEComas, the role of adjuvant therapy is not well defined. Kalyanasundaram et al. [Citation5] reported a case of a young female with a vaginal PEComa. The tumor recurred despite 4 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with vincristine, doxorubicin, and endoxan. Rigby et al. [Citation6] presented a case of an 11-year-old girl with metastatic PEComa arising from the left kidney. The patient was treated with a dacarbazine-based regimen first and later with imatinib mesylate based on tumor expression of c‐KIT. The treatment was later discontinued because of non-response.

One could argue for an adjuvant therapy in case of malignant features, however, clinicians should weigh possible advantages of a chemotherapeutic treatment to side effects. Previous cases reported failure of chemoradiation and therefore regular surveillance with routine imaging would be the appropriate policy. In our case, the tumor involved the excision margin so there may be some risk of local recurrence for which careful follow-up is warranted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Danilewicz M, Strzelczyk JM, Wagrowska-Danilewicz M. Perirenal perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) coexisting with other malignancies: a case report. Pol J Pathol. 2017;68(1):92–95.

- Singer E, Yau S, Johnson M. Retroperitoneal PEComa: case report and review of literature. Urol Case Rep. 2018;19:9–10.

- Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(12):1558–1575.

- Brimo F, Robinson B, Guo C, et al. Renal epithelioid angiomyolipoma with atypia: a series of 40 cases with emphasis on clinicopathologic prognostic indicators of malignancy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(5):715–722.

- Kalyanasundaram K, Parameswaran A, Mani R. Perivascular epithelioid tumor of urinary bladder and vagina. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2005;9(5):275–278.

- Rigby H, Yu W, Schmidt MH, et al. Lack of response of a metastatic renal perivascular epithelial cell tumor (PEComa) to successive courses of DTIC based-therapy and imatinib mesylate. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45(2):202–206.