Abstract

Introduction

Urolithiasis in renal allografts is relatively rare with an incidence of 0.17–4.40%. It is nonetheless an important issue, as there is a risk of obstruction, sepsis and even loss of the renal allograft. The management of stones in renal allografts remains challenging because of the anatomy, the renal denervation and the use of immunosuppressive medication.

Case presentation

This report discusses the ex-vivo treatment of asymptomatic nephrolithiasis in a living donor kidney allograft. A CT abdomen revealed a lower pole stone (5.9 × 5.5 × 5.0 mm; 920 HU) in the right kidney of the potential donor. After multidisciplinary discussion, it was decided to procure the right kidney despite the presence of a documented nephrolithiasis. After discussion with both donor and recipient, an ex-vivo flexible ureterorenoscopy for stone removal on the back table just before implantation of the allograft was planned. The stone was found in the lower pole covered by a thin film of the urothelium. The thin film of urothelium was opened with a laser and the stone fragments were retrieved with a basket. CT after one month showed no residual stones in the transplanted kidney.

Conclusion

Back-table endoscopy in a renal allograft is a feasible technique and should be discussed as an option in case of urolithiasis in a kidney that is considered for transplantation. Furthermore, the appropriate treatment of donor kidney lithiasis is another, although rare, method to expand the living donor renal allograft pool.

Introduction and background

Urolithiasis in renal allografts is a relatively rare condition with an incidence of only 0.17–4.40%. However, it can lead to major complications with the risk of obstruction, infections and even loss of the renal allograft [Citation1,Citation2]. Lerut et al. already described the difficulties nephrolithiasis can pose in renal allografts in 1979 [Citation3]. Four decades later, the management of stones in renal allografts remains challenging because of the anatomy, the renal denervation and the use of immunosuppressive medication [Citation1].

These kidney stones can already be present at the time of transplantation (donor-gifted) or can develop after transplantation (de-novo formation) [Citation1,Citation2]. The majority of existing stones are found in renal allografts from deceased donors, as they do not undergo imaging prior to kidney harvest [Citation2]. The evaluation of potential donors aims to identify co-morbidities. Extensive imaging, using CT-scans, allows discovering nephrolithiasis more frequently [Citation1].

Case presentation

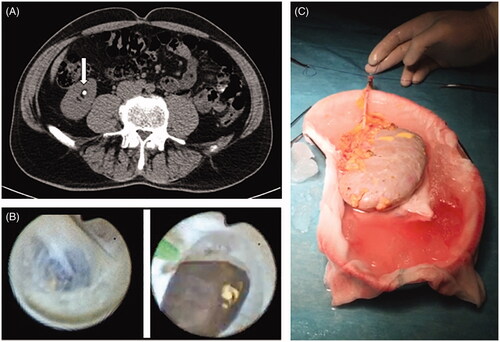

This report discusses the ex-vivo treatment of asymptomatic nephrolithiasis in a living donor kidney allograft. The donor was a healthy 61-year-old man with no significant medical history. The patient was screened as a potential kidney donor for a family member. A CT abdomen was performed as part of the routine transplant work-up. The CT revealed an asymptomatic lower pole stone (5.9 × 5.5 × 5.0 mm; 920 Hounsfield units) in the right kidney as shown in . The patient had a normal renal function with a serum creatinine of 73 µmol/L and an eGFR of 101 mL/min/1.73 m2. Additional diagnostic work-up and physical examination revealed no abnormalities.

Figure 1. (A) CT-scan showing the nephrolithiasis in the renal allograft. (B) Endoscopic image of the stone before and after opening the mucosa. (C) Set-up of the renal allograft on ice.

After multidisciplinary discussion, it was decided to procure the right kidney despite the presence of a documented nephrolithiasis. All treatment options related to the lithiasis were discussed including treatment before, during and after the donor nephrectomy of surveillance with eventual treatment in the recipient. Finally, it was decided, after discussion with both donor and recipient, to perform an ex-vivo stone removal on the back-table just before implantation of the allograft.

After the donor nephrectomy, the back-table was prepared for a flexible ureterorenoscopy (). In case this would not be successful, a pyelotomy was considered for stone extraction. First, two stitches with a nonabsorbable suture (Ethilon® nyon suture 3/0; Ethicon; Sommerville; New Jersey; USA) were placed in the distal part of the ureter to allow stabilization and introduction of a hybrid guidewire (straight tip Sensor guidewire 0.038′′ × 150 cm; Boston Scientific). The ureter was not spatulated. After positioning the guidewire, a flexible ureterorenoscope (URF-P6® 7.95French distal tip; Olympus; Hamburg; Germany) (URS) was advanced over the guidewire into the renal pelvis. Subsequently, all calyces were inspected. Fluoroscopic guidance was not used during this procedure. The stone was found in the lower pole of the kidney. However, it was still covered by a thin film of the urothelium. After opening the surrounding urothelium with a Holmium YAG laser (100 Watt; Lumenis Ltd.; Yokneam Illit; Israel) and single-use laser fiber (Flexiva TracTip®; Boston Scientific; Marlborough; Massachusetts; USA), all fragments were removed with a Nitinol tipless stone extractor (NCircle® 1.5French; 115 cm; Cook Medical; Bloomington; Indiana; USA) (). After final inspection, no residual stones were observed. The total operation time for the back-table endoscopy was 36 min.

The repaired right kidney allograft was successfully implanted in the right iliac fossa. Urologic continuity was restored using according to the Lich–Grégoir technique. A double-J stent (Bardex®, soft ureteral stent, 16 cm, 6 Fr; Bard; Murray Hill; New Jersey; USA) was left in situ and removed in the outpatient clinic after six weeks. The recipient reported minor stent-related symptoms. A CT-scan of the abdomen one month after surgery showed no residual stones.

Discussion

There is an imbalance between the need for renal allografts and the availability of potential donors [Citation4]. Ideally, a potential donor has no renal disease, infections, kidney stones or transmissible malignancy. In the case of stone-bearing donor kidneys, there is a potential risk of subsequential obstruction and infection if the stones are not extracted prior to the transplant, as well as a risk of stone recurrence in the recipient if the stones are treated prior to donation [Citation4,Citation5]. However, due to the shortage of living donors, the criteria for donors have been expanded, allowing kidneys with nephrolithiasis to be transplanted [Citation4]. However, according to the Amsterdam Forum on the Care of the Live Kidney Donor criteria 2005, living donors with kidney stones are still excluded from donation if they have a high risk of stone recurrence, such as hypercalciuria, hyperuricosuria, metabolic acidosis, cystinuria, hyperoxaluria and combination recurrent urinary tract infections [Citation4,Citation5].

Although nephrolithiasis in a renal allograft have been reported since the late seventies, it is a relatively rare condition. Nonetheless, due to the risk of obstruction, sepsis and even loss of the renal allograft, treatment of these kidney stones is important [Citation1–3]. This leads to the discussion of whether or not a donor is accepted in the case of nephrolithiasis and which kidney should be donated, the stone-bearing or non-stone-bearing kidney. If the stone-bearing kidney is chosen for donation, it prompts the following question: what to do with the kidney stone? The different options are treatment of the stone in the donor prior to harvesting, treating the stone in the harvested kidney prior to transplantation (back-table treatment), or treating the stone in the recipient after transplantation. All of these options have their specific benefits and risks, both from a medical as well as from an ethical point of view. Nowadays, most of the centers perform a two-staged procedure. They start by making the donor kidney stone-free in one procedure and then continue with the transplantation in a second, separate procedure [Citation4].

Pushkar et al. described 14 cases with back-table endoscopic stone treatment. All were living donors with unilateral, asymptomatic nephrolithiasis between four and ten millimeters who underwent standard donor screening and therefore are comparable with this case [Citation4]. They put the donor kidney on the ice during the back-table treatment. The authors first spatulated the ureter and started the procedure with a semi-rigid URS. They only used a flexible URS if necessary. When the kidney stone was found, they relocated it to the pyelum with a basket or forceps and extracted it via a pyelotomy. Only if a pyelotomy was not feasible, they would use a laser to fragment the stone and extract the pieces through the ureter [Citation4]. Mean operation time in their series was 28 min. A double-J stent was placed for four weeks. The stone-free rate was 93% and no major complications (modified Clavien-Dindo classification ≥3) were recorded [Citation4].

Literature on the back-table treatment of nephrolithiasis in renal allografts is scarce. A literature search on PubMed (Medline) resulted in eight articles describing this specific procedure, as presented in . A total of 76 procedures were described in these eight papers [Citation4,Citation6–12]. Semi-rigid, as well as flexible URS, were used to reach the stone. Baskets and forceps in combination with laser lithotripsy were used to retrieve the stone. The overall complication rate was low with 7.5% minor complications and only one major complication. The literature review shows that the post-transplant stone-free rate varied between 89% and 100%. More importantly, Schade et al. did not find a stone in the collecting system in four of the 23 patients (17%) [Citation9]. Olsburgh et al. encountered the same problem in six out of there 17 patients (35%) [Citation11].

Table 1. Literature overview for back-table endoscopic treatment of nephrolithiasis in renal allografts.

This shows that ex-vivo, back-table endoscopy is a feasible option in the treatment of stone-bearing donor kidneys. This technique has a high stone-free rate, and the overall complication rate is low. Another major advantage of the back-table stone treatment is that no additional treatment of the donor or recipient is needed. However, it remains important to have different treatment strategies available and discuss these options with the patient and the transplant team.

Conclusion

Back-table endoscopy in a renal allograft is a feasible technique and should be discussed as an option in case of urolithiasis in a kidney that is considered for transplantation. Furthermore, the appropriate treatment of donor kidney lithiasis is another, although rare, method to expand the living donor renal allograft pool.

Author contributions

MMEL Henderickx: Protocol/project development, patient care, data collection or management, manuscript writing/editing; J Baard: Protocol/project development, patient care, data collection or management, manuscript writing/editing; PC Wesselman van Helmond: Patient care, manuscript writing/editing; I Jansen: Data collection or management, manuscript writing/editing; GM Kamphuis: Protocol/project development, patient care, manuscript writing/editing.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient described in this case report.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Reeves T, Agarwal V, Somani BK. Donor and post-transplant ureteroscopy for stone disease in patients with renal transplant: evidence from a systematic review. Curr Opin Urol. 2019;29:548–555.

- Wong KA, Olsburgh J. Management of stones in renal transplant. Curr Opin Urol. 2013;23:175–179.

- Lerut J, Lerut T, Gruwez JA, et al. Case profile: donor graft lithiasis; unusual complication of renal transplantation. Urology. 1979;14:627–628.

- Pushkar P, Agarwal A, Kumar S, et al. Endourological management of live donors with urolithiasis at the time of donor nephrectomy: a single center experience. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47:1123–1127.

- Delmonico F. A report of the Amsterdam Forum on the Care of the Live Kidney Donor: data and medical guidelines. Transplantation. 2005;79:S53–S66.

- Lin CH, Zhang ZF, Wang J, et al. Application of ureterorenoscope and flexible ureterorenoscope lithotripsy in removing calculus from extracorporeal living donor renal graft: a single-center experience. Ren Fail. 2017;39:561–565.

- Trivedi A, Patel S, Devra A, et al. Management of calculi in a donor kidney. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:761–762.

- Machen GL, Milburn PA, Lowry PS, et al. Ex-vivo ureteroscopy of deceased donor kidneys. Can Urol Assoc J. 2017;11:251–253.

- Schade GR, Wolf JS, Faerber GJ. Ex-vivo ureteroscopy at the time of live donor nephrectomy. J Endourol. 2011;25:1405–1409.

- Vasdev N, Moir J, Dosani MT, et al. Endourological management of urolithiasis in donor kidneys prior to renal transplant. ISRN Urol. 2011;2011:1–5.

- Olsburgh J, Thomas K, Wong K, et al. Incidental renal stones in potential live kidney donors: prevalence, assessment and donation, including role of ex vivo ureteroscopy. BJU Int. 2013;111:784–792.

- Ganpule A, Vyas JB, Sheladia C, et al. Management of urolithiasis in live-related kidney donors. J Endourol. 2013;27:245–250.