Abstract

Background: Academic detailing (AD) is a defined form of educational outreach that can be used to influence decision making and reduce unwarranted variation in healthcare delivery. This paper describes the results of the proof of concept phase of the ADVOCATE Field Studies. This study evaluated the feasibility, acceptability and usefulness of AD reinforced with feedback data, to promote prevention-oriented, patient-centred and evidence-based oral healthcare delivery by general dental practitioners (GDPs).

Methods: In the Field Studies, six groups of GDPs (n = 39) were recruited in The Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. Each group had four meetings reinforced with feedback data for open discussions on dental practice and healthcare delivery. Conventional and directed content analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data collected from focus group interviews, debriefing interviews, field notes and evaluation forms.

Results: A total of nine themes were identified. Seven themes related to the process of the Field Studies and covered experiences, barriers and facilitators to AD group meetings, data collection and the use of an electronic dashboard for data presentation and storage. Two themes related to the outcomes of the study, describing how GDPs perceived they made changes to their clinical practice as a result of the Field Studies.

Conclusions: The ADVOCATE Field Studies approach offers a novel way of collecting and providing feedback to care providers which has the potential to reduce variation oral healthcare delivery. AD plus feedback data is a useful, feasible approach which creates awareness and gives insight into care delivery processes. Some logistic and technical barriers to adoption were identified, which if resolved would further improve the approach and likely increase the acceptability amongst GDPs.

Introduction

Reducing variation is a key in optimizing oral healthcare delivery. ‘Optimal quality care’ refers to care that is accessible, reliable, efficient and based on the best available evidence, and incorporating individual patient preferences [Citation1,Citation2]. Even though all stakeholders aim for optimal quality care, actual care may vary in many aspects including safety, effectiveness, equity and the individualization of care using the values and preferences of patients. Unwarranted variation in care delivery should concern oral health professionals, as it may indicate wasteful, ineffective practices and the possibility that care is not optimally serving the needs of the patient. This may be due to, for example, mistaken or limited individual professional knowledge, attitudes or skills, or disparate organizational performance [Citation3].

However, some variation in healthcare delivery should be expected, given that differences in patient characteristics and preferences will occur naturally in different populations. Therefore, determining from feedback data alone whether variation in healthcare delivery is warranted or unwarranted is often fraught with difficulties. Data-driven normative judgements about the provided care should usually be resisted, given that many clinical situations involve decision making that is preference-sensitive. Giving and receiving feedback data about variation in healthcare delivery requires creation of a receptive learning environment because feedback data are poised to generate denial, discomfort and feelings of blame. If clinicians can self-identify areas in which change in oral healthcare delivery may be needed, providing positive, constructive feedback data in those areas could create an environment in which behaviour change may be internally recognized, accepted and subsequently acted upon [Citation4].

Awareness of the importance of variation in healthcare delivery increased following Wennberg et al. reporting in 1988 on regional variation in healthcare [Citation5]. Variation in healthcare delivery exists on national, regional and local levels and is driven by societal, organizational, cultural and individual factors. It is no longer a question of whether variation in healthcare delivery exists, but more a question on how to define, identify and, if appropriate, reduce the variation in healthcare delivery [Citation6]. A review evaluating different implementation strategies for changing physician practice to reduce variation in healthcare delivery showed that active and multifaceted approaches, such as academic detailing (AD), lead to greater effects than traditional passive approaches, such as dissemination of information [Citation7]. AD is a defined form of educational outreach which involves face-to-face education of healthcare practitioners by other trained healthcare professionals, often peers. AD has most commonly been used to explore and improve prescribing by doctors. Even though similar challenges concerning variation in healthcare delivery exist in dentistry, multifaceted approaches involving AD have not been explored for changing practice in dentistry.

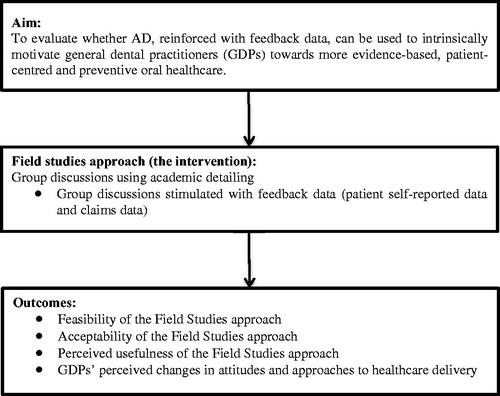

In 2015, the ADVOCATE (Added Value for Oral care) project commenced. ADVOCATE is an EU Horizon 2020 project that aims to optimize delivery of oral healthcare in order to improve the wellbeing of the European population. As part of the ADVOCATE project, Field Studies have been conducted. The Field Studies are a proof of concept study aimed at evaluating whether AD, reinforced with feedback data, can be used to intrinsically motivate general dental practitioners (GDPs) towards more evidence-based, patient-centred and preventive oral healthcare. Using qualitative methods, the Field Studies evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and usefulness of AD reinforced with feedback data from the GDPs’ perspective, and whether this approach motivated GDPs to change their clinical practice. This paper presents the results of the Field Studies evaluation.

Methods

Design

The design of the Field Studies has been described in full detail elsewhere [Citation8]. Local groups of GDPs were brought together to discuss variations and similarities in their provided oral healthcare and to reflect on optimizing their oral healthcare delivery. shows the overall approach used for the Field Studies. The groups of GDPs, called ‘Academic Detailing Groups’ (ADGs), were moderated by a Steward. Stewards were purposefully recruited by the ADVOCATE research team. They were dentists in active clinical practice with good interpersonal skills and prior experience as evidence-based educators of their peers. They received additional training in the methods of AD from the research team according to the principles defined by Soumerai and Avorn [Citation9].

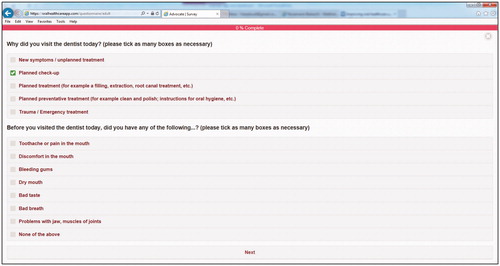

Feedback data on GDPs’ healthcare delivery and oral health outcomes were used to inform and stimulate the discussions in the ADGs. Data were obtained from claims data and patient self-reported data. The patient self-reported data were collected through an online questionnaire administered in dental practice using a tablet (the questionnaire application) (). The range of topics on which data was collected was based on an earlier study which defined measures of oral healthcare that were considered important, relevant and useful by GDPs, patients, health insurers and policymakers [Citation10]. Claims data were obtained on a regional level from the health insurers or health authorities in each participating country. The acquisition of these claims data is described in an earlier publication [Citation11].

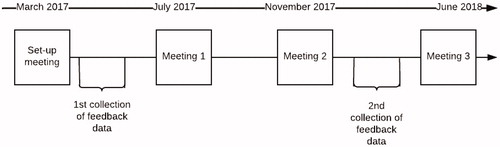

The Field Studies were conducted in Denmark, Germany, and The Netherlands and ran from January 2017 until June 2018. Six ADG groups (total GDPs = 39) were recruited – two groups in each country. A convenience sample of GDPs were recruited by the Stewards from within their own and extended network. As earlier research showed that a sample between 5 and 8 participants per group would be ideal for qualitative research [Citation12], the Stewards were asked to attempt to recruit a sample of 6–8 GDPs per group. The ADGs came together for four meetings over a period of 13 months; a set-up meeting and ADG meetings 1, 2 and 3. In the set-up meeting, GDPs were informed about the Field Studies and were provided with the resources to collect the patient self-reported data in their dental practice. Patient self-reported data were collected twice for a period of two months: after the set-up meeting and three months before meeting 3. shows the timeline of the ADG meetings and data collection periods.

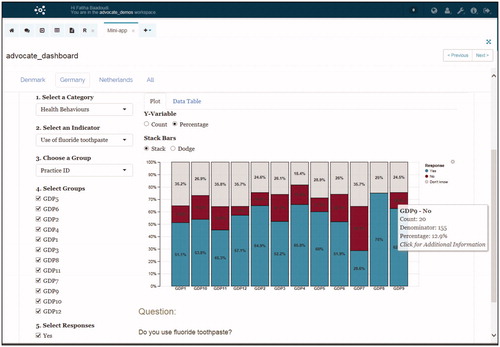

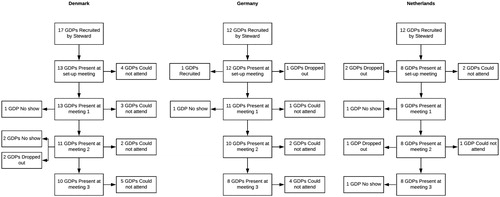

Aggregated summaries of anonymized feedback data were made available for Stewards and every participating GDP in an online database, referred to as the ‘Dashboard’ (). In ADG meetings 1–3, moderated, open, non-judgmental and confidential discussions on healthcare delivery took place using the dashboard to stimulate discussions. During each of the ADG meetings, GDPs and the Steward discussed a selection of feedback data. The initial selection of the feedback data was initially made by the Stewards and discussed before each meeting with the ADVOCATE research team (preparatory meetings) and finally discussed in the ADG meetings. During the discussion on the differences and similarities of the selected feedback data, GDPs were encouraged to reflect on their motivations for decisions made in current clinical practice, to discuss any underlying evidence, and to identify action points for improvement of their own clinical practice. shows the attendance of GDPs at each ADG per country.

Evaluation data

The approach to evaluate the Field Studies was pre-specified and has been described in the design paper [Citation8]. In brief, demographic background information of GDPs was collected by means of a questionnaire during the set-up meeting. The primary data used to assess the feasibility, acceptability and usefulness of the Field Studies approach, and to document GDPs’ perceived changes in their motivation and healthcare delivery, were collected by semi-structured focus groups interviews with GDPs during the last ADG meetings (meeting 3). Secondary data sources were notes from Stewards made during the ADG meetings, and debriefing telephone interviews of the research team with Stewards and evaluation forms completed by GDPs collected after the ADG meetings.

Six focus group interviews with the GDPs were conducted in June 2018 at the end of meeting 3. An interview guide consisting of open-ended questions was used [Citation8]. Questions were centred on experiences with and perceived usefulness of the AD approach and the feedback data, actual changes made to clinical practice, or precursors of change such as reported changes in attitudes or approaches to healthcare delivery.

The focus group interviews were facilitated by a local researcher with experience in conducting focus group interviews recruited through the ADVOCATE research team. Interviewers were otherwise not involved with the ADGs and they did not have any relationship with the GDPs. The focus group interviews were conducted in a quiet room at the local dental faculties and were held in the local language of the GDPs. Prior to the focus group interview, a meeting took place involving the research team and each interviewer to standardize procedures according to the interview guide. The interview guide was available in the local language as well as in English. The focus group interviews lasted approximately 50 min. Interviewers made notes during the focus group interviews. All sessions were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. All transcripts were translated to English for analysis by an external professional translation company and checked by the interviewers.

Data analysis

The software programme MaxQDA was used for analysis of the qualitative data collected. Data analysis of the focus group interviews was undertaken using a conventional content analysis approach [Citation13]. Identified categories were data-driven and not preconceived categories. Initially, the focus group transcripts were read and re-read by one researcher (FB) to get an overall understanding of the data. Thereafter, segments of data were coded by identifying persistent and recurrent words or phrases. The codes were then grouped according to themes, which allowed the identification of sub-themes. The identification of themes and sub-themes resulted in the initial coding framework. As a sense-check, all authors assessed the framework on comprehensiveness. Directed content analysis was used to analyze the additional information retrieved from debriefings, notes and evaluation forms [Citation13]. The initial coding framework of themes and sub-themes retrieved from conventional content analysis was used as the basis for coding the additional information. When segments of data were identified that did not fit in the coding framework, new codes were added to the framework. Where segments of data were determined to represent a topic that was not previously determined, a new theme emerged. Finally, the codes were checked for duplicates and whether they were categorized correctly. The analysis of the qualitative data was conducted by one author (FB), and concurrently discussed with a second author (DD).

Results

Demographic information for the 39 GDPs who participated is shown in . Three GDPs dropped out of the study because of personal reasons. A total of 26 GDPs was able to attend the focus group interviews. Seven GDPs could not attend because of logistical reasons.

Table 1. Characteristics of GDPs (n = 39) participating in the Field Studies.

Conventional content analysis of the focus group interviews resulted in the identification of seven themes; ADG meetings, patient questionnaire application, claims data, dashboard, overall opinion of the Field Studies, perceived results and GDPs’ views on oral healthcare. Directed content analysis of the additional data from the evaluation forms, field notes and debriefings defined two additional themes; recruitment of GDPs and communication with GDPs. The total of nine themes could be grouped into two broad categories: (1) the process and (2) the outcomes of the Field Studies’ approach. A description for each theme is provided below. Within each theme, barriers and facilitators related to the Field Studies were identified, and are presented in . Quotes corresponding to each theme are shown in . Additional descriptive results from the evaluation forms are presented in .

Table 2. Barriers and facilitators in the ADVOCATE Field Studies.

Table 3. Quotes from the focus groups and forms.

Table 4. Average evaluation ADG-meetings by GDPs.

The process of the Field Studies

Theme 1: recruitment of GDPs

Stewards had different experiences with recruiting GDPs for the Field Studies. Some Stewards found it relatively easy to recruit GDPs within their network, whereas for others it took a lot of effort to explain what participation involved and to obtain agreement from GDPs to participate. The main reasons for GDPs not participating was not having enough time and not seeing an added benefit from participating (; Quotes 1–3).

Theme 2: communication with GDPs

Stewards mainly kept in touch with the GDPs via email. Occasionally a phone call or a visit to the GDPs’ practice was arranged when support was considered helpful, particularly with regard to collecting patient feedback data (Quote 4). Clear and directed communication in emails between the Stewards and GDPs was experienced by the Stewards to work better than more open questions – for example, asking the GDPs for suggestions or their opinion (Quote 5).

Theme 3: ADG meetings

Steward

GDPs were generally very positive about the role of the Stewards. They found them committed, well prepared and organized (Quote 6). GDPs appreciated the way the Stewards provided a neutral and positive environment for open discussion (Quote 7). The GDPs considered the Stewards’ role in the Field Studies approach to be essential, particularly through summarising discussion points, clarifying and interpreting the feedback data, and navigating the dashboard (Quote 8).

Logistics

Stewards experienced the preparatory meetings with the research team as useful, especially in order to decide what feedback data from the dashboard to discuss in the ADG meeting. Overall, the Stewards had little difficulty in arranging a place, date and time for the ADG meetings. Occasionally, more effort was needed to plan the meetings; during holiday seasons or when GDPs responded late to the emails with suggested dates (Quote 9). Attendance of GDPs varied across the different groups; illness, running late in dental practice and having other commitments were main reasons for non-attendance. It was considered disruptive when group members were absent or late. GDPs that missed a meeting felt they lagged behind (Quote 10).

Experiences

The feedback data and having conversations on healthcare delivery were perceived as motivating and interesting. The GDPs felt the meetings triggered them to reflect on decisions underlying their oral healthcare delivery (Quote 11). The GDPs agreed that feedback data provided to them as a stand-alone resource would not be sufficient to understand, discuss and reflect on the data (Quote 12). GDPs felt that the roles of the Steward as data interpreter and moderator of group discussions were essential to make sense of the data and to identify action points for change in clinical practice. The GDPs liked to compare themselves with similar practices from other localities. All GDPs were engaged in the discussions. The ADG meetings provided an open and safe place to learn and have constructive discussions about their healthcare delivery, relative to peers (Quotes 13 and 14). Meeting 2 was perceived by some GDPs as less useful because there were no new feedback data.

Theme 4: patient questionnaire application

Questionnaire

Overall, both Stewards and GDPs thought that the questionnaire was too long and took about ten minutes to be filled in by the patients. A few GDPs also reported that some of the questions were unclear, difficult to complete, and would benefit from some revision. However, GDPs did mention that the patients who completed the questionnaire did not mind the length. This was also confirmed by the patients in the questionnaire; the majority (91%) stated the time it took to fill in the questionnaire was reasonable and the majority of patients (93%) reported to find the questionnaire easy to understand. GDPs reported that patients liked to provide their dentist with feedback and were curious to see the results. The questionnaire being anonymous was an important factor for the patients (Quote 15). GDPs recommended to shorten and simplify the questionnaire so that it requires less time to complete. It was suggested to have the option of GDPs being able to make a selection of the questions (Quote 16). Some GDPs would also have liked the questionnaire to have been available in other languages (Quote 17).

Data collection

Many GDPs encountered challenges with regard to the collection of patient self-reported data in their dental practice. Most GDPs considered two months were too short to collect data from their patients. However, some of the GDPs felt they could have collected more data if more effort had been put into it. Getting data collection established into the practices’ daily routine was difficult for most GDPs. GDPs preferred to have someone outside of the clinical dental team to help with data collection in the practice. GDPs reported that the assistant or receptionist found it a lot of work to hand out the questionnaire tablets to the patients due to time constraints, especially when some patients required more detailed explanations (Quote 18). Other stated reasons for limited data collection was that the assistant or receptionist did not take responsibility or did not perceive it as a priority task. During the ADG meetings, it was reflected that the GDPs with the most data collected were the practices where the assistant or receptionist was actively involved (Quote 19). The GDPs recommended providing an incentive for the assistant or other means of motivation to improve data collection.

Another factor that could have hindered data collection was the fact that because of the design of the app, patients could not leave any questions blank or save questions for later; all questions had to be completed before data was submitted. Sometimes patients would be disturbed by their accompanying children or would be called to the GDP while completing the questionnaire, resulting in loss of data (Quote 20). Also, many patients asked whether they could fill in the questionnaire at home, yet the questionnaire – as currently designed – could only be completed at the practice on the tablet. Patients and GDPs would have liked the option of a paper or a link via e-mail to fill in at a later time (Quote 21). Some GDPs mentioned that there were instances where they felt it was inappropriate to ask the patient to fill in the questionnaire for example after the extraction of a tooth (Quote 22).

GDPs and Stewards questioned the use of tablets for data collection. Technical problems and difficulty with the login were perceived as annoying and time-consuming. Also, GDPs felt uncomfortable having the tablets in the waiting room, fearing they could be stolen. Having the tablet mounted to a pillar in the waiting room could have provided a possible solution. Furthermore, the GDPs felt that by using an electronic device for data collection could have introduced bias; older and patients with limited literacy had more difficulties filling in the questionnaire and the dental team – rightly or wrongly – would sometimes make a judgment and not ask some individual patients to fill in the questionnaire (Quotes 23 and 24). Despite these reported barriers, some GDPs reported to be surprised how well the majority of the patients coped with the devices (Quote 25). They also saw it as an advantage that an electronic questionnaire avoided having a lot of paper circulating.

Feedback data

Once the feedback data were collected and compiled, GDPs found the patient self-reported data interesting and useful (Quote 26). They considered it a good stimulator for discussions about clinical practice. It was reassuring for the GDPs to find few apparent large differences when they compared their data with other GDPs. However, the GDPs discussed the validity and representativeness of the data, recognizing that the number of collected questionnaires per dentist were often small and selective, and some questions might have been misinterpreted by the patients (Quote 27). Some GDPs considered the data to be unreliable since the data did not always match with the GDPs’ expectations; they were interested to know which patients provided which information. All GDPs agreed that no hard conclusions about healthcare delivery could be drawn from this data. GDPs felt that with larger numbers of participating patients the data would have had more meaning to them. They agreed that the feedback data were useful as tool to reflect on healthcare delivery and to stimulate discussions among peers, but not for normative purposes. Some GDPs indicated they used the feedback data as an indication of whether their clinical practice was similar to their peers, while not making any conclusions about the delivered healthcare (Quote 28).

Theme 5: claims data

Mainly, GDPs and Stewards found the claims data unclear and irrelevant because it was based on aggregated data from regions within countries (Quote 29). GDPs would find claims data as feedback data more interesting if they were aggregated at a practice or individual GDP level. The claims data as it was presented were seen by GDPs as being not sufficiently granular for the discussions held in the groups. Summarising and presenting the data in a more attractive and more intuitive way would make it more relevant for the GDPs. GDPs did find cross-country comparisons interesting (Quote 30), with the caveat that data should be viewed with caution because it originated from different oral healthcare systems.

Theme 6: dashboard

Usage

Despite the caveats described in Themes 4 and 5, the GDPs generally found it interesting and useful to see their own data in the dashboard and see the compiled patient self-reported data (Quote 31). Some of the GDPs were disappointed they could not see changes they made in their healthcare delivery over time in the dashboard (Quote 32). It was the Stewards who analyzed the data in the dashboard. The majority of GDPs did not access their dashboard outside the ADG meetings, despite them having access to the dashboard. The main reason given by the GDPs was not having enough time or difficulties with logging in. Furthermore, some GDPs did not consider it their role to look at the dashboard outside the ADG meetings (Quote 33).

Functionality

The dashboard was seen by the GDPs as being complex, unclear and not intuitive (Quote 34). The GDPs would have preferred simpler, summarized data. It was suggested to have the information from the dashboard in a user-friendly app. GDPs found the mails they received from the host of the dashboard that announced maintenance or updates to the database very frustrating (Quote 35).

Theme 7: overall opinion of the Field Studies

The GDPs found that the Field Studies provided a way to get an understanding of the clinical practice of colleagues, an opportunity which otherwise they would have been denied. According to the GDPs, the strength of the approach was that feedback data were collected from their patients and yet were not used to form normative judgements. GDPs had previous negative experiences with claims data being used for benchmarking performance by insurance companies or health authorities (Quote 36). The GDPs also indicated that they appreciated receiving feedback on their healthcare delivery from a peer visiting their dental practice.

Some GDPs felt that participating in a project that took a year was considered too long. The Field Studies did not run very smoothly according to the GDPs, because of the technical problems with the patient-app questionnaire and dashboard. They did recognize that this was mainly because it was a proof of concept study and therefore this could be expected. Furthermore, some GDPs reported in the focus groups that the aim of the study was unclear to them until the end of the study (Quote 37). This is in contradiction with the results from the evaluation forms were the majority of GDPs (set-up meeting; 95%, meeting 1; 87%, meeting 2; 96% and meeting 3; 80%) agreed or strongly agreed with the objective being clearly defined, as shown in . The GDPs considered that the participating GDPs were a selective sample who were already open to new approaches, information and changes (Quote 38). The GDPs anticipated that many of their colleagues would not voluntarily participate in similar projects.

The outcome of the Field Studies

Theme 8: perceived results

The GDPs initially stated that the Field Studies did not change their clinical practice. However, they then stated that the feedback data had provided them with new insights that patients often have an imperfect understanding or recollection of the healthcare they receive. For example, many patients reported that the dentists had not asked for their current medical history, while GDPs were certain that they did. This made the GDPs aware of the importance of better communication, or the potential effects of partial or incomplete recall. Based on this insight, GDPs reported they had made changes in their communication with patients (Quote 39). Most of the GDPs indicated that as a result they now try to ask questions differently, for example, by clearly asking for the patient’s preferences and by explaining their actions more explicitly to the patients (Quote 40). This is also reflected in the action points formed during the ADG meetings as shown in .

Table 5. Action points derived during the ADG meetings.

Some of the GDPs also mentioned that in addition to understanding and recall, adherence to, for example, a preventive recommendation may potentially be facilitated by improved communication (Quote 41). Furthermore, GDPs recognized that better communication requires active effort and energy, and it does not provide an immediate, explicit reward. Some GDPs indicated that they would like to receive support in improving their communication skills, and this would be appropriate for the other oral healthcare workers in the dental team. The influence of the patients’ individual situation and preferences on decisions regarding healthcare delivery was discussed during the ADG meetings, and how to incorporate this in decision making and conversations with the patient.

Overall, the feedback data were considered an eye-opener for the GDPs. They thought the patient self-reported feedback data would be very useful to improve discussions about the quality of healthcare during team meetings in the dental practice. Especially in group practices where people might have difficulty in providing feedback directly to colleagues, GDPs saw feedback data from the patients as a useful, independent facilitator of discussions (Quote 42).

Theme 9: GDPs’ views on oral healthcare

GDPs found it very important that their patients are satisfied with the healthcare provided. GDPs recognized that dentistry is more than dental treatments, and that patient involvement and patient-centred healthcare are becoming increasingly important aspects of their work (Quote 43). However, some GDPs did mention that patient satisfaction does not necessarily mean that good healthcare is provided. They consider the patients are sometimes fallible when making judgements that are normative in nature (Quote 44).

Discussion

Group discussions using AD reinforced with feedback data are hypothesized to stimulate healthcare providers to calibrate their care delivery, leading to reduction of unwarranted variation. The goal of this proof of concept study was to initially explore whether this approach is a useful, feasible and acceptable way of intrinsically motivating GDPs towards a more evidence-based, patient-centred and preventive oral healthcare.

The results of this study suggest that GDPs become intrinsically motivated to change practice when they are engaged by AD. This is in line with earlier studies showing AD stimulates intrinsic motivation to improve care delivery [Citation14]. The evaluation of the Field Studies found that GDPs became stimulated to improve communication with their patients. The Field Studies approach facilitated the identification of topics within oral healthcare were where mutual understanding of GDPs and patients is potentially not optimal. This can enable GDPs to adapt their patient communication and potentially tailor their healthcare delivery to individual patients.

However, the timeframe of the Field Studies and the nature of the available data precluded detection of quantitative changes in communicational aspects of oral healthcare delivery – for example, changes in the frequency of performing of preference-sensitive procedures. Significant reduction in variation of delivered care was not part of the design of this pilot study, was not measured and was beyond the scope of this study. However, participating GDPs did see potential for the Field Studies approach to aid in reducing variation in oral healthcare delivery. Furthermore, the two data collection periods were too short to provide evidence for causal and temporal relationships of the Field Studies approach and changes in care delivery. Future research involving larger numbers of GDPs over longer periods of time is necessary to measure the effect of the Field Studies approach on variation in care.

The focus on prevention during the ADG meetings was closely linked to communication, patient understanding and a realization of the difficulties in communicating the importance of prevention. This points to the need for preventive interventions based on the individual patient. Evidence-based healthcare may have been difficult for GDPs and Stewards to relate to in the ADG meetings, this reflected by a lack of evidence-based healthcare specific actions points formulated (). Evidence-based healthcare might not have been in the foreground during the ADG discussions, because of the current availability of evidence based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in dentistry [Citation15]. RCTs and other outcomes oriented studies in dentistry that have evaluated clinically relevant interventions are relatively few in number [Citation16]. In addition, studies have shown that the awareness of evidence-based practice amongst GDPs is low [Citation17–19].

GDPs experienced the Field Studies approach as useful, providing them with the opportunity to reflect and learn about healthcare delivery and create awareness on variation in healthcare and patient needs. The GDPs regarded being aware of similarities in challenges in providing healthcare and discussing attitudes to practice between peers as comforting and reassuring. The approach provides the opportunity to function as a calibration tool; GDPs used the feedback data and the ADG meetings to see where they stand in their healthcare delivery compared to their peers. This is in line with the findings from Meyer and Singh [Citation4] who stated that preventable harms by underuse and overuse of diagnostic tests and other resources can be resolved by developing well-calibrated healthcare providers. Calibration facilitates foundational knowledge on decision making (aligning competing needs and demands) and gives confidence to the healthcare provider [Citation4].

This study shows that overall it is feasible to provide AD reinforced with feedback data in a group setting to GDPs in Denmark, Germany and The Netherlands. Stewards succeeded in moderating three meetings with GDPs and guided them through the dashboard and the interpretation of the feedback data. However, a number of barriers have been identified that need to be overcome in order to implement the Field Studies approach on a larger scale. It is likely that recruitment of GDPs to participate in AD should be stimulated by incorporating the approach in already existing systems or protocols, or by incentivizing participation. Barriers relating to the data collection in the dental practice should be reduced – for example by involving the entire oral healthcare team in the set-up meetings and data collection, instead of expecting the GDPs to successfully cascade this to their in-practice colleagues. Technical problems should be resolved and improvements made to the deployment and use of both the tablet-based patient questionnaire application and the dashboard, for example by obtaining patient self-reported data via a variety of other means, such as the patient’s own smart phone. Finally, the role of the Stewards was considered essential to initially interpret the data in the dashboard and to organize and facilitate discussions. If AD is undertaken on a wider basis, adequate capacity and resources will be needed for initial training and ongoing support to the Stewards.

Several limitations regarding the Field Studies should be considered. The use of a small convenience sample of GDPs might have resulted in a very selective sample GDPs. This limits the ability to generalize the findings. The purpose of using qualitative methods in this study was to evaluate the Field Studies approach, to gain a deeper understanding of barriers and facilitators for implementing the approach on a larger scale in dentistry. However, the data should not be considered as observational data about whether actual changes were made to GDPs’ dental practice. Furthermore, a limitation of the Field Studies approach is that no information was available on the response rate of patients to the questionnaire. Non-participation may be due to a fear of breach of confidentiality, a negative attitude towards oral healthcare and surveys in general [Citation20]. This might have introduced selection bias amongst the patients filling in the questionnaire. Subsequent research should attempt to collect data on non-response. Furthermore, claims data were only available on a macro level, providing limited insight into the healthcare provided. Also, patient self-reported feedback data were limited since, for example, an interrupted time series comparison was not possible. If the same patients fill in the questionnaire at baseline and follow-up, the reliability of the data would be improved.

In conclusion, the Field Studies approach is feasible, useful and acceptable, when appropriate adjustments have been made to mitigate reduce the barriers to implementation. The approach establishes a novel and useful way of collecting and providing feedback data within dentistry. One of the important lessons learned was that by participating in AD, the GDPs became more reflective about their own practice and consultation skills, how they compared to their peers, and they gained insights into how they were perceived by their patients. This may be seen as an important first step to raise awareness about and give more meaning to variation in healthcare delivery.

More information is required on the scalability and reproducibility of the Field studies approach before implementation strategies can be developed. However, if those further small-scale studies confirm these results, and when appropriate adjustments have been made to mitigate the barriers to implementation, the development and evaluation of large scale AD approaches using patient-derived feedback data would be appropriate.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the VU medical ethical committee in The Netherlands, the Heidelberg Ethics Committee in Germany and the Copenhagen Videnskabsetiske Komiteer in Denmark and the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Author contributions

F. Baâdoudi, MSc (PhD-student), contributed to design, data interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; D. Duijster, PhD (assistant professor), contributed to design, data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript; N. Maskrey, MD (research consultant), contributed to conception, design, data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript; F. M. Ali, BSc (research assistant), contributed to data collection and critically revised the manuscript; K. Rosing, PhD (Postdoc researcher), contributed to data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript; G. J. M. G. van der Heijden, PhD (Professor), contributed to conception, design and critically revised the manuscript; All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. F. Baadoudi and D. Duijster both have completed a course in qualitative methods in health research.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the contributors to the ADVOCATE project: the ADVOCATE Scientific Advisory Board – Stephen Birch, Martin Chalkley, Roger Ellwood, Ekatarina Fabrikant, Jeffery Fellows, Christopher Fox, Frank Fox, Dympna Kavanagh, John Lavis, Roger Matthews, Mariano Sanz, Paula Vassalo and Sandra White; the ADVOCATE General Assembly – Renske van der Kaaden, Lisa Bøge Christensen, Gail Douglas, Kenneth Eaton, Gerard Gavin, Jochem Walker, Stefan Listl, Gabor Nagy, Karen O’Hanlon, Andrew Taylor, Helen Whelton, Noel Woods; the ADVOCATE Ethics Advisory Board – Mary Donnelly, Eckert Feifel, Jon Fistein, Evert-Ben van Veen and Agnes Zana; the ADVOCATE project coordinator, Maria Tobin; and the co-workers of the ADVOCATE project. We specially thank the GDPs and Stewards participating in this study. We would also like to thank Ana-Lena Trescher, Olivier Kalmus and Lisa Bøge Christensen for their help in data collection and transcription of Focus groups and Olivier Kalmus in liaising with the local ethics committee in Germany.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s). All authors have no personal, commercial, political or interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Institute of Medicine. Best care at lower cost. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2013.

- Leatherman S, Sutherland K. Patient and public experience in the NHS. The Health Foundation; 2007.

- CARE, NHS Right. The NHS Atlas of variation in healthcare September 2015: reducing unwarranted variation to increase value and improve quality. Public Health England; 2011.

- Meyer AND, Singh H. The path to diagnostic excellence includes feedback to calibrate how clinicians think. JAMA. 2019;321(8):737.

- Wennberg JE, Mulley AG, Hanley D, et al. An assessment of prostatectomy for benign urinary tract obstruction. JAMA. 1988;259(20):3027.

- Mulley AG. Inconvenient truths about supplier induced demand and unwarranted variation in medical practice. BMJ. 2009;339(2):b4073.

- Mostofian F, Ruban C, Simunovic N, et al. Changing physician behavior: what works? Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(1):75–84.

- Baâdoudi F, Duijster D, Maskrey N, et al. Improving oral healthcare using academic detailing – design of the ADVOCATE Field Studies. Acta Odontol Scand. 2019;77:1–8.

- Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Principles of educational outreach (‘academic detailing’) to improve clinical decision making. JAMA. 1990;263(4):549–556.

- Baâdoudi F, Trescher A, Duijster D, et al. A consensus-based set of measures for oral health care. J Dent Res. 2017;96(8):881–887.

- Haux C, Rosing K, Kalmus O, et al. Acquiring routinely collected claims data from multiple European health insurances for dental research: lessons learned. Dusseldorf: German Medical Science GMS Publishing House; 2017. p. 283.

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2015.

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288.

- Bloom BS. Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(3):380–385.

- Beyers RM. Evidence-based dentistry: a general practitioner’s perspective. J Can Dent Assoc. 1999;65:620–622.

- Kishore M, Panat SR, Aggarwal A, et al. Evidence based dental care: integrating clinical expertise with systematic research. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(2):259–262.

- Haron IM, Sabti MY, Omar R. Awareness, knowledge and practice of evidence-based dentistry amongst dentists in Kuwait. Eur J Dent Educ. 2012;16(1):e47–e52.

- Iqbal A, Glenny A-M. General dental practitioners' knowledge of and attitudes towards evidence based practice. Br Dent J. 2002;193(10):587–591.

- Yusof ZYM, Han LJ, San PP, et al. Evidence-based practice among a group of Malaysian dental practitioners. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(11):1333–1342.

- Korkeila K, Suominen S, Ahvenainen J, et al. Non-response and related factors in a nation-wide health survey. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17(11):991–999.