Abstract

Objective: To reduce the gap between what can be achieved in endodontic treatments and the observed treatment outcome among general dental practitioners, the present study set out to assess the status of the endodontic practices as regards to knowledge and self-assessed skills among general dental practitioners in Sweden and Norway.

Material and method: The questionnaire was sent to 1384 general dental practitioners. It contained questions regarding access to continuing education in endodontics, sources of knowledge for clinical management of patients, post-operative follow-ups, self-assessed success-rate, and the initial diagnosis impact on the outcome of endodontic treatments.

Results: The response rate was 61.4%. Almost half estimated their endodontic success-rate to be 90%. About two-thirds of the respondents did not know, or did not believe, that the initial diagnosis could affect the outcome of their endodontic treatments. Respondents who did not believe the diagnosis could impact the outcome were more likely to estimate their success rate as the highest (p<.001). Less than half performed post-operative follow-ups a year after treatment. A third of the respondents had not attended any continuing endodontic education.

Conclusion: Dentists who do not receive regular feedback on their treatments may lack insight into their own shortcomings. If this is combined with insufficient knowledge and understanding it may result in sub-par endodontic treatments being performed. It is important to have reliable ways to communicate current endodontic knowledge and to establish robust methods that may help dentists accurately assess their own performance in endodontics.

Introduction

Epidemiological surveys have shown apical periodontitis to be frequently associated with root-filled teeth [Citation1]. Despite technological advances made during the last couple of decades, studies continue to find high frequencies of substandard root fillings [Citation2,Citation3]. Some reports show improvement in the quality of root fillings as assessed radiographically, but without a concomitant improvement in the apical health in connection with the root-filled teeth [Citation4,Citation5]. Of course, the real key factor for the outcome of endodontic treatments is whether microorganisms are present in the root canal system or not [Citation6], and radiographs do not tell us anything about possible microbial contamination.

While general dental practitioners (GDPs) often report high confidence in their clinical endodontic skills [Citation7,Citation8] studies show that root canal treatments performed by specialists in endodontics, or at dental student clinics, have a better outcome than root canal treatments performed in general dental care [Citation9,Citation10]. Studies indicate that many GDPs lack sufficient knowledge of the factors important in determining the outcome of root canal treatments [Citation7,Citation8] and that basic principles, for instance, the aseptic control and follow-ups, are often ignored [Citation8,Citation11,Citation12].

To reduce the gap between what can be achieved in endodontic treatments and the observed treatment outcome among GDPs, it seems relevant to assess the GDPs’ endodontic treatment protocols and sources of knowledge. The present study is the second part of a twofold questionnaire survey set out to investigate different aspects of GDPs’ endodontic management of patients. In the first part, infection prevention and control measures were assessed [Citation13]. The aim of the present part of the questionnaire survey is to investigate other aspects that may affect the outcome: The status of the endodontic practices among GDPs as regards to knowledge, attitudes, self-assessed skills, and whether the GDPs have access to continuing endodontic education.

Material and method

An invitation to take part in the questionnaire was sent by email to all GDPs working in: The public dental care in two counties (Västra Götaland and Skåne) in Sweden (n 984), the public dental care in three counties (Trøndelag, Møre og Romsdal, and Telemark) in Norway (n 231), and the private dental care chain Colosseum Smile AB in Sweden (n 169). The questionnaire was checked and revised on the context of validity by a statistician at the University of Gothenburg and by being piloted by 3 GDPs. The questionnaire was modified in accordance with their comments, mostly by being re-worded to clarify the questions and responses, and by changing the order of the questions to make it more coherent for the respondents. The questionnaires sent to Norway had been translated into Norwegian and reviewed by a Norwegian specialist in endodontics.

The questionnaire consisted of 9 questions regarding continuing professional education in endodontics, post-operative follow-ups, self-assessed success-rate, and the initial diagnosis’ impact on treatment outcome. The respondents were also asked questions regarding their age, gender and year of graduation. A comment box for additional remarks was included in the questionnaire. The questionnaire was fully anonymous. It was accompanied by an explanatory covering letter. It was distributed to the recipients using esMaker (Entergate AB, Halmstad, Sweden) during three periods in 2016–2017. Two reminders were sent to all recipients with an interval of two weeks in between.

Completed questionnaires were analysed using SPSS version 25 (Chicago, IL, USA). A non-response analysis was carried out. Blank answers on questions were counted as missing, and only valid responses were included in the descriptive analysis of each question, where absolute and relative frequencies were determined. The association between variables was examined by cross-tabulations and the statistical significance of such relationships determined by Pearson’s chi-squared test and Fishers’ exact test. Statistical tests were two-tailed at the 5% significance level.

Results

Fity-one of the questionnaires could not be delivered as the recipient had moved or retired. Of the delivered 1333 questionnaires; 499 were not returned, 5 returned empty, and 10 returned with the information that the recipient was not a GDP, did not work clinically, or did not perform endodontic treatments. The overall response rate was 61.4% (n 819). The questions were answered by 98.7–100% of the participants. The non-response analysis showed an even gender and age distribution compared to the full target sample. There were no significant differences regarding the distribution of gender, age, or years in the profession ().

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents.

Successful treatment outcome

The majority estimated their endodontic success-rate to be 75% or above, and more than half did not believe or did not know if the initial diagnosis could impact the outcome of endodontic treatments (). GDPs who did not believe the initial diagnosis could affect treatment outcome were more likely to estimate their success rate as the highest (p<.001). Swedish GDPs were more likely to believe the initial diagnosis did not affect the outcome of treatments: 27.5% compared to 14.6% in Norway (p=.029). 7 GDPs commented that they considered just being able to finish a root filling without any mishaps a successful outcome, while 23 respondents considered endodontic treatments successful so long as the patients did not experience symptoms. GDPs who did not enjoy performing RCT were less likely to estimate their success-rate as the highest (p<.001).

Table 2. Self-assessed outcome, post-operative follow-ups and continuing endodontic education.

Post-operative follow-ups

Most GDPs stated that they performed post-operative follow-ups with radiographs (). 5.8% (n 48) only performed follow-ups if the patient showed symptoms, or if the tooth needed prosthodontic restoration. 4.0% (n 33) remarked that they tried to do follow-ups the following year, but external factors affected how many years would pass until they saw the patient again. GDPs in Norway were more likely to do a follow-up 1 year after treatment: 65.6% compared to 41.6% in Sweden (p<.001).

Sources of knowledge

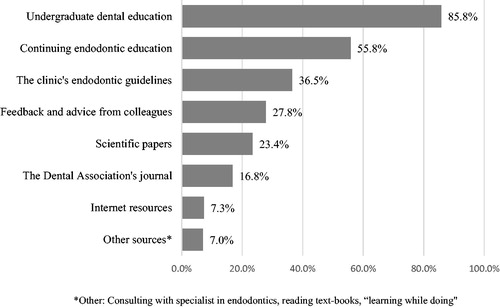

Most stated 1–4 sources of knowledge for their clinical management of patients (). 16.9% (n 139) stated undergraduate dental education as the only source of knowledge, 65% of those had 5 years or less in the profession. GDPs with over 30 years in the profession were more likely to state continuing endodontic education as their only source of knowledge (p=.001).

Continuing endodontic education

A majority wanted to attend more courses in endodontics, but a third of the respondents had not attended a single course in endodontics after their undergraduate training (). Dentists who had graduated after 2006 were more likely to not have attended any continuing endodontic education (p<.001). 46.6% of the GDPs who had attended courses in endodontics had done so within the last 3 years. 82.3% of the GDPs who had attended courses in endodontics listed them as a source of knowledge for their clinical management of patients. 12 GDPs had not attended any continuing endodontic education in over 20 years.

Discussion

Most respondents held that their clinical endodontic management of patients worked well, and almost half of the GDPs estimated their endodontic success-rate to be 90%, indicating that many have a high level of self-confidence in their ability to perform endodontic treatments. Similar findings have been reported in other studies [Citation7,Citation8]. A contributing factor to the good self-confidence may lie in how the individual dentist defines a successful treatment outcome. The European Society of Endodontology defines a favourable outcome as: ‘Absence of pain, swelling and other symptoms, no sinus tract, no loss of function and radiological evidence of a normal periodontal ligament space around the root’ [Citation14]. But, some GDPs had adopted variations of ‘functional retention’ [Citation15] as their definition of a successful outcome, while other GDPs just defined it as being able to complete a root filling without any mishaps. Moreover, over half of the respondents either did not know, or did not believe, that the initial diagnosis could affect the outcome of their endodontic treatments. The GDPs who did not believe the diagnosis could impact the outcome were also more likely to estimate their success rate as the highest. This lends support to the notion that many GDPs view endodontic treatments as a technical procedure to keep a patient symptom-free rather than a way of treating, or preventing, infection in the root canal system [Citation7,Citation16]. The potential lack of understanding of microbiological factors’ influence on the outcome of endodontic treatments is a troubling notion since dentists need to be able to evaluate preoperative factors accurately. A lack of microbiological understanding might also impact how meticulously infection prevention and control measures are carried out during endodontic treatments.

The recommendation from the European Society of Endodontology is that root canal treatments should be assessed at least after one year and subsequently as required [Citation14]. Although a majority of the GDPs reported that they performed post-operative follow-ups, a different picture emerged when asked when the follow-ups were performed. Less than half carried out follow-ups one year after root canal treatment, and more than a quarter did not have a set routine for endodontic follow-ups. This is in line with other studies that have found endodontic post-operative follow-ups to be infrequently performed [Citation11,Citation12,Citation17]. Post-operative follow-ups are not only important for the patient, but also for the dentist. Without systematic follow-ups, the GDPs will not obtain knowledge about their performance or gain awareness of any shortcomings that may be important for changing their treatment strategies. However, the idea of follow-ups being important for feedback may fall short if the GDP simply defines a patient being symptom-free as a successful treatment outcome.

Most GDPs based their endodontic management of patients on two to four sources of knowledge, with undergraduate dental education and continuing endodontic education being most frequently stated. This is not a surprising find, as many dentists continue the practice they have been taught during their undergraduate training [Citation12,Citation18]. But, almost a fifth of the respondents based their clinical management of patients solely on their undergraduate training. While many were relatively new to the profession, the undergraduate training probably cannot cover all aspects of endodontology in the depth needed in everyday clinical practice. ‘Learning while doing’ could work well at a practice that encourages in-house development of skills, but some GDPs are left to their own devices in clinics that lack systematic in-house learning [Citation19]. There were respondents who commented on a lack of regular case discussions with colleagues, which perhaps is why only a quarter considered feedback and advice from colleagues as a source of knowledge for their management of patients. Receiving feedback, watching others practice and engaging in case reviews is important for developing insight into professional performance and for identifying gaps in knowledge [Citation20,Citation21]. Without regular feedback, there is a risk that clinical practices will be impaired.

A third of the respondents had not attended any continuing endodontic education, and the use of other sources of knowledge (internet resources, scientific papers, and so on) was relatively low. This could indicate that several GDPs may find it difficult to stay up to date on current practices and guidelines. Among the respondents who had attended courses in endodontics, a majority stated that they used the continuing education as a source of knowledge in their clinical management of patients. Research also indicates that continuing dental education can play a key role in changing practices in dentistry [Citation22]. However, the outcome of endodontic treatments does not automatically improve by attending continuing endodontic education [Citation23,Citation24]. To initiate and maintain relevant changes, there must be an awareness of a need for change and a motivation to implement the changes [Citation25]. So, the crucial question is whether the focus of courses correctly identifies shortcomings that need to be addressed and whether GDPs attending the courses correctly identifies their own shortcomings – otherwise educational efforts may miss the mark. Unfortunately, studies show that poorly performing individuals often are unaware of their gaps in knowledge and skills [Citation20,Citation25], so it is probably not possible for all GDPs to individually identify their own weaknesses correctly. Perhaps platforms for performance assessment feedback are needed as a complement to help GDPs direct their learning towards improving their performance in their specific areas of weakness.

A limitation of the methodology in this study was that the pilot group was small and the questionnaire was not tested with similar questions to assess the reliability of the responses. There are communication barriers that can give inaccurate results as the respondents may understand questions and definitions differently than was intended [Citation26]. For instance, the GDPs’ self-assessed success-rate may have been lower had we included the European Society of Endodontology’s definition of a favourable treatment outcome in the questionnaire. Furthermore, the self-reported performance of post-operative follow-ups could differ from what is actually done in the clinical practice, as there is a risk of recall bias when asking someone what they do and not assessing the actual behaviour objectively as a comparison. Another limitation is the inability to probe responses in a written questionnaire. For example, the finding that respondents in Norway were more likely than respondents in Sweden to perform follow-ups one year after treatment, raised questions on the origin of this difference: Is it educational, a result of differences in how the dental care systems are organised, or something else? Since the questionnaire does not offer the opportunity to clarify these issues, further investigation is warranted.

To sum it up, GDPs with a lack of understanding of microbiological factors’ impact on the outcome of endodontic treatments, combined with limited insight into their own level of knowledge and clinical performance, could be a recipe for poorly performed endodontic treatments. The results from this study indicate that many GDPs may receive insufficient feedback on their performance in endodontics, and that they also may find it difficult to stay up-to-date. Therefore, it is vital to establish robust methods that help GDPs accurately assess their own performance in endodontics. It is also important to have reliable ways to communicate essential endodontic knowledge and modern guidelines, so GDPs can stay competent for current practice. The process will likely have to start with a critical appraisal of both undergraduate endodontic training and continuing endodontic education, especially as regards to endodontic microbiological factors, self-assessments, and outcome measures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Eriksen HM, Kirkevang L-L, Petersson K. Endodontic epidemiology and treatment outcome: general considerations. Endod Topics. 2002;2(1):1–9.

- Kirkevang L-L, Vaeth M, Wenzel A. Ten-year follow-up of root filled teeth: a radiographic study of a Danish population. Int Endod J. 2014;47(10):980–988.

- Peters LB, Lindeboom JA, Elst ME, et al. Prevalence of apical periodontitis relative to endodontic treatment in an adult Dutch population: a repeated cross-sectional study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111(4):523–528.

- Eckerbom M, Flygare L, Magnusson T. A 20-year follow-up study of endodontic variables and apical status in a Swedish population. Int Endod J. 2007;40(12):940–948.

- Frisk F, Hugoson A, Hakeberg M. Technical quality of root fillings and periapical status in root filled teeth in Jonkoping, Sweden. Int Endod J. 2008;41(11):958–968.

- Kakehashi S, Stanley HR, Fitzgerald RJ. The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20(3):340–349.

- Bjørndal L, Laustsen MH, Reit C. Danish practitioners’ assessment of factors influencing the outcome of endodontic treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(4):570–575.

- Saunders WP, Chestnutt IG, Saunders EM. Factors influencing the diagnosis and management of teeth with pulpal and periradicular disease by general dental practitioners. Part 1. Br Dent J. 1999;187(9):492–497.

- Ng YL, Mann V, Rahbaran S, et al. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: systematic review of the literature - part 1. Effects of study characteristics on probability of success. Int Endod J. 2007;40(12):921–939.

- Sjögren U, Hägglund B, Sundqvist G, et al. Factors affecting the long-term results of endodontic treatment. J Endod. 1990;16(10):498–504.

- Helminen SE, Vehkalahti M, Kerosuo E, et al. Quality evaluation of process of root canal treatments performed on young adults in Finnish public oral health service. J Dent. 2000;28(4):227–232.

- Markvart M, Fransson H, EndoReCo, Bjørndal L. Ten-year follow-up on adoption of endodontic technology and clinical guidelines amongst Danish general dental practitioners. Acta Odontol Scand. 2018;76(7):515–519.

- Malmberg L, Hägg E, Björkner AE. Endodontic infection control routines among general dental practitioners in Sweden and Norway: a questionnaire survey. Acta Odontol Scand. 2019;77(6):434–438.

- European Society of Endodontology. Quality guidelines for endodontic treatment: consensus report of the European Society of Endodontology. Int Endod J. 2006;39(12):921–930.

- Friedman S, Mor C. The success of endodontic therapy-healing and functionality. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2004;32(6):493–503.

- Kvist T, Hedén G, Reit C. Endodontic retreatment strategies used by general dental practitioners. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97(4):502–507.

- Koch M, Eriksson HG, Axelsson S, et al. Effect of educational intervention on adoption of new endodontic technology by general dental practitioners: a questionnaire survey. Int Endod J. 2009;42(4):313–321.

- Savani GM, Sabbah W, Sedgley CM, et al. Current trends in endodontic treatment by general dental practitioners: report of a United States national survey. J Endod. 2014;40(5):618–624.

- McColl E, Smith M, Whitworth J, et al. Barriers to improving endodontic care: the views of NHS practitioners. Br Dent J. 1999;186(11):564–568.

- Hays RB, Jolly BC, Caldon LJ, et al. Is insight important? measuring capacity to change performance. Med Educ. 2002;36(10):965–971.

- Holden JD, Cox SJ, Hargreaves S. Avoiding isolation and gaining insight. BMJ. 2012;344:e868.

- Watt R, McGlone P, Evans D, et al. The facilitating factors and barriers influencing change in dental practice in a sample of English general dental practitioners. Br Dent J. 2004;197(8):485–489.

- Koch M, Wolf E, Tegelberg Å, et al. Effect of education intervention on the quality and long-term outcomes of root canal treatment in general practice. Int Endod J. 2015;48(7):680–689.

- Dahlström L, Molander A, Reit C. Introducing nickel-titanium rotary instrumentation in a public dental service: The long-term effect on root filling quality. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112(6):814–819.

- Cochrane LJ, Olson CA, Murray S, et al. Gaps between knowing and doing: Understanding and assessing the barriers to optimal health care. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27(2):94–102.

- Choi BCK, Pak A. A catalog of biases in questionnaires. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(1):A13–A13.