Abstract

Objectives

The aim was to examine how patients describe and perceive their dental fear (DF) in diagnostic interviews.

Material and Methods

The sample consisted of dentally anxious patients according to the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS), who had problems coping with conventional dental treatment. The voluntary participants (n = 7, aged 31–62 years) attended a diagnostic interview aiming to map their DF before dental treatment. The data were analysed by theory-driven qualitative content analysis. The themes consisted of the four components of DF: emotional, behavioural, cognitional, and physiological, derived from the Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear.

Results

Within these four themes, treated as the main categories, 27 additional categories related to the patients’ interpretations of DF were identified in three contexts: before, during and after dental treatment. 10 categories depicted difficult, uncontrollable, or ambivalent emotions; nine depicted behavioural patterns, strategies, or means; five depicted disturbing, strong, or long-lasting physiological reactions, including panic and anxiety symptoms. The remaining three categories related to cognitive components.

Conclusions

The results indicate that dental care professionals may gain comprehensive information about their patients’ DF by means of four component-based diagnostic interviews. This helps them to better identify and encounter patients in need of fear-sensitive dental care.

Trial registration number

NCT02919241

Background

Dentists frequently encounter patients suffering from dental fear/anxiety in their daily work. Representative studies in Nordic countries showed that every third Finnish person was somewhat or very much afraid of visiting a dentist and every tenth Swedish person reported severe or moderate dental anxiety [Citation1,Citation2]. Researchers have highlighted the negative consequences of dental fear using the concept of a vicious circle where dental avoidance leads to greater treatment need and problem-oriented visits [Citation3,Citation4]. In addition, qualitative study evidence has revealed the wide-ranging negative impacts of dental anxiety on people’s daily lives related to physiological, cognitive, behavioural, health and social aspects [Citation5]. Therefore, it has been proposed that individuals who suffer from the troublesome consequences of dental fear could benefit from an intervention that focuses on reducing avoidance behaviours [Citation6].

Furthermore, dentists may suffer stress from treating dentally anxious patients [Citation7]. Although a patient’s state of anxiety is reduced when dentists have information about this prior to care [Citation8], dentists rarely utilise this possibility [Citation9]. In order to specify a patient’s fears, it is recommended to measure their fear level before dental care by asking them a simple question about dental fear [Citation10,Citation11] or by using validated psychometric measures of dental anxiety [Citation12]. For example, the reliability of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) [Citation13] has been verified in studies [Citation14]. The three concepts of fear (= fear, anxiety, phobia) have been defined [Citation15] and considered in the quite new Index of Dental Fear and Anxiety (IDAF-4C+) [Citation16]. The first of the three modules in this index assess the emotional, behavioural, cognitive, and physiological components of the anxiety and fear response with eight items. In addition, the researchers have developed structured interview guides to obtain knowledge about more specific factors related to problem-oriented situations during an appointment [Citation17,Citation18]. When dental fear or anxiety is severe and disturbs a person’s daily life, it can meet the criteria for a specific phobia included in anxiety disorders, according to the criteria of psychiatric disorders, DSM-5 [Citation19].

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) alleviated severe dental fear in adults according to systematic reviews [Citation20,Citation21]. Usually, the interventions in studies were composed of the diagnostic interview and exposure to dental treatment. Already thirty years ago, investigators proposed that when dentists used an interpersonal cognitive technique in the interview, patients’ dental anxiety was reduced [Citation22]. Although the discussion and diagnostic interview seem to be essential for fear reduction in the context of studies, the significance/meaning of these in relation to actual patients is still unclear. In addition, only a few studies used qualitative methods to gain a deeper understanding of an individual patient’s perceptions of their dental fear. Most of the previous studies on dental fear applied grounded theory [Citation23–26] or thematic analysis [Citation5,Citation27]. Grounded theory studies aimed to explore the situation of dental phobic patients or their perceptions or experiences related to their fear [Citation23,Citation24], how they manage to undergo dental treatment [Citation25] and the factors used by those affected to maintain regular dental care after a dental fear intervention [Citation26]. One of the thematized studies concentrated on the fear-inducing triggers associated with dental treatment and on expectations prior to a dental encounter [Citation27]. Another focussed on the impacts of dental fear on daily living [Citation5]. Furthermore, two grounded theory studies explored the patient-dentist relationship [Citation28,Citation29].

Due to the lack of qualitative studies regarding a patient’s own perceptions of their dental fear in the context of a diagnostic interview, we wanted to study the multidimensional facets of dental fear to gain a better understanding of the phenomenon. The aim of this study was to examine how patients who suffer from dental fear/anxiety talk about their fear in the frame of a diagnostic interview based on four components of fear introduced in the Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear [Citation16,Citation30]. The research question is: How do the patients perceive and interpret their dental fear in terms of its four components – emotional, behavioural, cognitive, and physiological. What kinds of emotions, behaviours, cognitions, and physiological reactions do they relate to their dental fear when they talk about their fear in a diagnostic interview?

Materials and methods

Study design

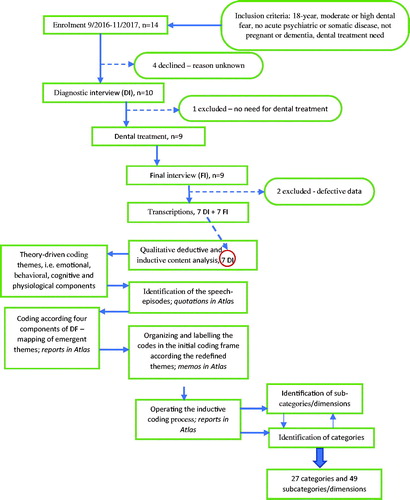

The qualitative study presented is a part of a larger intervention study which, after ethical approval from The Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Savo Hospital District (Registration number: 281/13.02.00/2016) in June 2016, was registered in the clinical study in ClinicalTrials.gov (identification number: NCT02919241). Based on a power analysis related to the decrease in level of dental fear, the required number of participants in the two study groups (I: diagnostic interview + One Session Treatment according to a protocol by Öst & Skaret [Citation31], II: diagnostic interview) was set to ten, aiming at 98% power with the confidence level of 0.05% and SD 2.8. The participants in the present study were those who participated in the in the diagnostic interview (group II), after which they were treated by their own dentist (). The voluntary participants came from three separate private dental practices in the eastern part of Finland and they gave informed consent before participating in the study. Their own dentists evaluated participants’ suitability for the study according to the following inclusion criteria: a minimum of 18 years of age and identification of some kind of problem during conventional dental treatment related to fear. In addition, the participants had to report moderate or severe dental anxiety according to the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) [Citation13], at least 11 out of the maximum of 25 points [Citation32]. Candidates who were recorded as having an acute mental or somatic disease, dementia or pregnant women were excluded from the study, because dental treatment after the diagnostic interview was a part of the study protocol. 14 participants were recruited between September 2016 and November 2017. Four participants declined to participate in the study as is usual in studies involving a sensitive topic. We were not able to gain any knowledge about them due to the ethical principles related to the research procedure. One participant was excluded from the study, because she did not need dental care. Thus, nine participants were treated once by their own dentist; thereafter they attended the final interview. Because of default tape-recorded material in two cases, the final sample consisted of five women and two men. A subsequent study will report the effects of the whole intervention study.

Diagnostic interviews

Diagnostic interviews were conducted by the first author, who is a dentist and has studied psychology. A diagnostic interview guide with dental fear questionnaires was used to ensure the internal consistency of the study; interviews consisted of questions regarding participants’ answers in the quantitative scales, an individual semi-structured fear assessment questionnaire according Milgrom et al. [Citation17] and the behavioural analysis derived from Öst’s diagnostic interview model [Citation31]. The focus was fully on participants’ own responses. The researcher asked open-ended questions followed by targeted questions without commenting on the answers. The structure of the interviews allowed for concentrating on the participants’ own perceptions or interpretations of their fear. Another aim was building trust between the researcher and the participants when the researcher listened carefully. The interviews lasted from one to two hours, depending on a participant’s talkativeness. All interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A professional translator translated the quotations from Finnish to English.

Analysis

The method used in the study was theory-driven qualitative content analysis with inductive and deductive elements [Citation33]. At the beginning of the analysis, the notion of four components of DF (described in the Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear [Citation15,Citation16]), was used as a broad conceptual framework and organising principle for approaching participants’ descriptions about their DF. In the first phase of analysis, the first author conducted in-depth reading of the data and identified all the speech-episodes in which the participants talk about their DF in terms of its four components (emotional, behavioural, cognitional and physiological), by using Atlas.ti 8 software (see ). She conducted data-driven thematic analysis and mapped the emergent themes according to the four components. The participants talk that related to four components of fear occurred in sentences of various lengths, which all were included in the units of analysis. After identifying all meanings, the first author organised the initial coding frame; codes related to emotions (n = 13), behavioural strategies (n = 10), cognitions regarding dental fear (n = 8) and physiological reactions (n = 6).

The first phase of analysis showed that all of the participants’ descriptions about their DF could be loosely categorised under four large themes, i.e. data was not forced into predetermined categories. However, the first phase and the initial coding frame revealed that the participants’ descriptions about their DF was diverse within the four categories in terms their thematic content. Thus, in the second phase, the first and second author identified the detailed contents (what the fear is about) and contexts (what situations or events the fear is associated with) of fear within each of the four themes and labelled the codes in the coding frame.

In the third phase of analysis, the first author proceeded with coding by identifying additional subcategories and categories within the four main categories. Categories and subcategories/dimensions were produced by looking at similarities and differences in the ways the contents and contexts of fear were described by the participants. To ensure the reliability of coding, the second author conducted a similar coding. Next, the coding done by the two authors were compared and discussed and as a result, the codes were partly redefined and renamed. Finally, all authors familiarised themselves with the categories and subcategories, and the final representation of categories was composed. Thus, the coding process involved intensive reading of data as well as dialogue between researchers. The end result of the analysis was the identification of 27 categories and 69 subcategories, shown in . In the following section, we will present our results by providing data extracts that were selected after systematic review of the material and that best illustrated the findings.

Results

Our analysis revealed that when participants reflected on their dental fear, the descriptions of their emotions, behaviour and physiological reactions fell within three contexts: before, during and after dental care. We will present our findings according to this structure. Although the participants’ descriptions of their cognitions were not organised directly according to these three contexts, we decided to integrate the results concerning the cognitive components of fear into our other results, which will be presented in accordance with the three identified contexts (see ). We identified 27 categories that illuminated the various facets of fear in four main categories: 24 of them related to difficult, uncontrollable or ambivalent emotions; self-coping behavioural patterns, strategies or means; disturbing, strong or long-lasting physiological reactions, including panic and anxiety symptoms. The remaining three categories related to cognitive components of fear. In addition, we identified 49 sub-categories and 20 dimensions.

Table 1. The contexts and contents of the main categories and the number of categories/sub-categories or dimensions related to them.

Table 2. Categories and subcategories/dimensions before dental treatment.

Table 3. Categories and subcategories/dimensions during dental treatment.

Table 4. Categories and subcategories after dental treatment.

Context: before dental treatment

Participants’ fears were activated before an upcoming appointment for several reasons and led to increasing anxiety when previous experiences and negative expectations of the upcoming dental treatment revolved in participants’ minds. Participant’s expressed behaviour conflicted with behavioural patterns towards participating in dental care. Physiological reactions worsened the quality of participants’ daily life. The lack of confidence towards dental care visits illustrated their cognitions.

Content: difficult emotions

In most cases, the content of the fear was clear. Nearly all participants could name situations, where the fear emerged and many explained that a new dental treatment situation was scary: ˈBecause it was new to me and the dentist was new, the situation caused even more anxiety than usual and I would worry about the appointment for several days in advanceˈ. Some participants felt embarrassment/shame about the fear. Furthermore, many participants described the activation of fear after making an appointment: ˈI’m constantly afraid of it, and I mean constantly. It’s a miracle I can even hold the phone straight when calling to book the appointmentˈ. But sometimes the fear was undefined before dental treatment. The participants reported about an unpleasant feeling or anxiety related to the upcoming appointment: ˈI may be slightly anxious already the previous evening, but the feeling is most intensive in the morning of, just before waking up. In fact, the anxiety is often what wakes me upˈ. Additionally, it was typical that the current fears were connected with earlier experiences. Nearly all participants told about their earlier experiences and fearful memories of past situations. They described about flashbacks related to intimidating treatments and procedures: ˈAfter the dentist went to fetch the tongs, I jumped up and fled the room. That’s the mental image I always carry with meˈ.

Content: self-coping behavioural patterns

All participants told about avoidance behaviour and that they had avoided dental care at some point of their lives. The consequences of intense dental fear were to postpone/cancel an appointment or avoid treatment for as long as possible. But it was typical that although the person postponed an appointment, he/she did not cancel it after the booking: ˈI didn’t quite cancel the appointment, but I kept putting it offˈ. Exposure behaviour was typical, too, and nearly all participants forced themselves to visit the dentist in an acute situation or in the case of other serious problems in the mouth. One reason behind this behaviour was the fear of pain. One participant explained that they tended to challenge themselves to face the situation: ˈI’ve always somehow managed to find the courage … You just tell yourself that it’s going to be fine, let’s just get it over withˈ. Most participants tried to use medicines or harmful substances to control fear. In other words, they managed the pain with painkillers instead of visiting the dentist or calmed themselves with tranquillizer or tobacco. Some used self-help to alleviate their fear. For example, they aimed to calm themselves by doing mental imagery or relaxation exercises: ˈI try to calm my mind, even if I can’t get to sleep easily or at all the previous nightˈ. Furthermore, most had found other means to alleviate their fear, for example by choosing a treatment time spontaneously or selecting the place of treatment based on a recommendation, turning to social support, avoiding thoughts of fearful situations, visiting the dentist with low expectations or counting down the time before the appointment.

Content: disturbing physiological reactions

Many participants described difficulties sleeping: ˈFor several weeks before an upcoming dentist’s appointment, I have a hard time sleeping and can have nightmaresˈ. Additionally, many reported clear physiological reactions, for example increased heart rate or perspiration. Restlessness was typical one day before an appointment and many participants reported that they had difficulties in doing their job because of the anxiety:

ˈAll day at work even, my heart beats much faster than normally and the thought constantly enters my mind. Just thinking about it repulses me and I can’t stop thinking about it all dayˈ.

Content: cognitions related to dental fear

Origins of fear. Because all participants described earlier negative treatment experiences, the interpretation was that the previous experiences underlie the fear and unconsciously affect the current dental care visits. Nearly all expressed the role of the overbearing professional caregiver in the development of fear. Furthermore, participants had learned that dentists’ styles in dealing with fearful patients vary, and they were worried about the dentist’s ability to recognise a patient’s fear. Most participants described that their fear would be alleviated if the dentist knew about it, and a trustful relationship was seen as a prerequisite for this: ˈ…because I have such an intense fear, to show it and properly talk about it with a dentist, I’d first need to trust the dentist – I couldn’t just go to any random dentist and explain how I feelˈ. Many participants had noticed alternations in fear intensity, and they reported that fear had been stronger earlier in their lives. The intensity of fear related to the up-coming treatment and commonly the situation was not as fearful as the person had anticipated:

The worst part is sitting in the waiting room and listening to the sounds from other rooms. You start thinking whether it’d be best to just run away …lately, it’s gotten a little better … because the dentist will really be understanding when they know they’re dealing with a patient who is afraid.

Only one participant told that he had always feared the dentist. Usually the participants saw that their own dysfunctional explanation of fear perpetuated the negative situation, because they considered their situation regarding fear as abnormal and it deviated from others’ situations. Some participants thought that the fear was just ˈbetween the earsˈ and some saw that it was related to a traumatic situation during childhood. Additionally, many participants perceived the connection between dental fear and other fears/psychiatric disorders/problems:

… The first time I felt panic wasn’t at a dentist, but in Egypt, while visiting the tombs … That’s when I first remember the feeling I now also get there [in the dentist’s chair] … I wonder if something was triggered back then … the same feeling of panic, that I really need to get out of the situation right this minute and can’t control myself at all.

Context: during dental treatment

Even though the intense emotions and physiological reactions were nearly out of participants’ control, they had invented ways to cope with their strong reactions. The extremely difficult situation forced them to find behavioural strategies to control physiological distress. Cognitions revealed that the participants were aware of the factors alleviating their dental fear.

Content: uncontrollable emotions

Nearly all participants were able to name/identify the most fearful aspect and we labelled the category, the fear of an extreme reaction, including fear of an allergenic reaction, fear of choking, fear of drowning, shortness of breath or fear of a panic attack: ˈSometimes I’ve had a feeling of drowning just thinking about having to go againˈ. Furthermore, most participants told about the fear of failure in a technical procedure, especially in local anaesthesia regarding the right location for the injection or pain during injection. Many mentioned the fear related to the dentist’s behaviour. All participants recognised objects of fear, which were described in three subcategories: fear of pain, fear of injections and distrust in their own ability to cope with the fear: ˈDuring a root canal treatment, I’m afraid of whether I can keep my mouth open ‒ what if it snaps shut while the spikes are in there? ˈ. Additionally, most participants felt uncertainty and they were worried about the dentist’s unclear language and about sounds/smells at the dentist’s office. Recollection of previous treatment situations during dental treatment was also typical, and the participants remembered fearful situations from the past: ˈ…that horrible memory of fleeing from there is all I can remember, and the stench used to be nauseating back in the day. These days, the smell isn’t that bad, even if they have all those chemicals thereˈ.

Content: behavioural coping strategies

The first conflicting behavioural patterns towards participating in dental care was active/passive actions. Most participants had difficulties in coping with the treatment and tolerating the fear: ˈI wonder what’s going to happen, whether or not I’m going to panicˈ. Many ended up striving to control one’s own physiological reactions and emotions: ˈI don’t allow it [the feeling of choking], even if it may feel as though it’s about to come up, I’ve always managed to stop it somehowˈ. While aiming to be active and manage the oppressive situation, many participants had ended up clasping their hands or stopping a procedure mid-treatment or signalling the dentist to pause treatment. The patients took initiative in previous actions. Although the dentist offered the option to interrupt the treatment, one participant was reluctant to accept it: ˈThe dentist even told me to raise my hand at any point if I feel like it, but of course I didn’t raise it as it didn’t really take that long to replace the fillingˈ. Most participants had turned to seeking helpful strategies for coping with their fear. For example, some participants told that they try to concentrate on breathing, relaxing themselves or practicing mindfulness: ˈ… at the point when it starts to feel like you might not be able to breathe, it helps to really focus on taking deep breaths through the noseˈ. Furthermore, the participants described actions they had found suitable, such as having antihistamine medicine in reserve, closing their eyes and thinking of the words of songs or concentrating on sounds during treatment: ˈThe squeaky sound that the machine [saliva ejector] makes is somehow calmingˈ. The other conflicting pattern was the tendency to manage on one’s own/seeking support from caregivers. Some participants were outspoken about their fear: ˈI remember declaring already at the door that I’m scared and not to hold back on the anestheticˈ, others avoided talking about it: ˈI’ve never told anyone about it [my dental fear]. It was the dentist who noticed it eventuallyˈ.

Content: strong physiological reactions

Most participants told about panic and anxiety symptoms when they described their dental fear: ˈBecause it [the anesthetic] takes a while to take effect, it didn’t really help at the moment I needed it and the panic was pretty overwhelmingˈ; ˈIt was like – well, I used to suffer from panic attacks, and the experience was pretty similar to thoseˈ. Furthermore, they explained other extremely strong physiological reactions, for example increased heart rate/palpitations: ˈI always say that I’m not having an allergenic reaction, I’m hypersensitive to adrenaline and my body goes into overdrive… my heart starts beating terribly fast, my face turns red and I get all sweaty and feverishˈ. Furthermore, they described the sensation of fainting/feeling paralysed, the sensation of being strangled, difficulties in swallowing: ˈ…often, the dentist has to pause because I get an urge to start swallowingˈ and the feeling of a constricted throat: ˈI feel like there’s something blocking my airway and I can’t breatheˈ.

Content: cognitions related to dental fear

Fear-alleviating factors. All participants told about an understanding and empathetic attitude of the caregiver. Participants appreciated a friendly dentist who listened to them and they explained the variations in a dentist’s drilling style and ways of administering local anaesthesia. When they had found ˈa good dentistˈ who treated them well, they did not want to change their dentist. It was seen as important that the patient could explain her/his wishes:

The dentist I’ve been visiting lately is generally pleasant, because they listen and have come up with methods for letting me know how long the drilling will still take or what’s going to happen next, for example. That somehow helps me brace myself for it or tolerate it.

All participants struggled against their fear and they had employed strategies to mediate their emotions. Some found it useful to calm themselves by reassuring themselves that they can do it: ˈ… when your heart starts racing because of the dentist, you just try to keep a cool head at that pointˈ or by overcoming the worst fear or by thinking in a positive way. Although the participants knew that their fear was irrational, this did not alleviate the fear. They found it more helpful to distance themselves by turning thoughts to something else: ˈ… I’ve been able to manage fairly well so far … The trick is to focus your thoughts on something else than what’s going onˈ. Most participants had noticed the positive effects of regular dental care attendance; they thought that when they attended dental care regularly, their fear decreased, and it was easier to visit the dentist: ˈ Sure, there’s been huge progress as time has passed. Thinking back, a few years ago I wouldn’t even dream of going to the dentist unlike now. So, just going there has helped in easing my fear ˈ.

Context: after dental treatment

Participants’ doubts remained leading to ambivalent emotions and they realised only a few helpful means for coping with dental fear. The physiological stress symptoms, including the intense sensations were relieved after dental treatment. The cognitions reflected participants’ unsolved problems and questions after dental visits.

Content: ambivalent emotions

Some concerns bothered participants reflecting confusion about the treatment session. One participant, for example, did not know the reason for an odd reaction which appeared unclear to her. Difference in opinion with the dentist was another example: ˈAt the first visit, it remained unclear to me when the dentist announced I’ll be getting a denture. At that point, I just hoped I’d at least get a partial dentureˈ. Furthermore, the participants talked about dismissing previous positive experiences during dental visits and remembering only the negative appointments. Moreover, some told about their uncertainty of the necessity of a treatment: ˈThe reason for taking out a tooth remained unclear to meˈ.

Content: behavioural means for coping

Participants’ told about some actions they had used. We labelled the first one rewarding oneself, because the participant told that she rewarded herself by shopping for something nice. The second one revealed how the participants dealt with the difficult situation by becoming passive and therefore they were unable to handle the difficult situation afterwards, although it could be helpful: ˈI mean, apparently, I’m pretty good at compartmentalising thingsˈ.

Content: long-lasting physiological reactions

Many participants reported that while certain situations triggered symptoms of a panic attack, they also experienced the calming of physiological reactions afterwards.

Content: cognitions related to dental fear

Negative/fear-provoking factors. All participants had negative thoughts after dental visits. They described that plenty of similarities existed between the treatment situations that reminded them of pain. Some participants explained that they were anticipating pain during the treatment because of previous painful experiences or stories they had heard from others. Due to this, they usually felt that the treatment was painful, and they suffered from unpleasant emotions during treatment. Additionally, the dentist’s use of terms was sometimes thought to be unclear and this provoked more fear as well as suspicious thoughts towards the dentist and confusion about the treatment procedure:

… I’m always afraid that since I’ve had the fillings in for so long, what if there’s some horrible surprise waiting. Like when this tooth was taken out, I think it used to have fillings, but the dentist said something to the effect that the tooth had collapsed, and I just wondered what a collapsed tooth means.

Many participants thought that the prone position and having the dentist’s equipment in their mouth was scary. In addition, they described that they suffered due to a state of helplessness when they could not control themselves or the treatment: ˈEven if rationally I know I’m not going to choke, the emotion takes over … and it’s such a pointless fear; I don’t understand why I can’t get over itˈ . They described worries regarding their ability to cope with the fearful treatment procedures in the future, because they felt that they had to endure their difficult feelings alone. Somehow, they seemed to be helpless victims who struggled to survive and waited for the dentist to notice and react to their fear. Some participants had catastrophic thoughts related to swallowing. They did not know how to be and act during the treatment:

Because I don’t know whether I’m allowed to swallow or move, if the drill is going to go through to my brain if I move just a little, or what if I drown because of all the saliva in my throat ‒ I just don’t know what they’re so busily doing in there and I’m sitting here drowning.

All participants told about the harmful effects and negative consequences of their fear. For example, they described remembering the unpleasant feeling, memory disorders/paramnesia, avoidance behaviour or long gaps between appointments and emergency treatments, being repulsed by dental treatment, deterioration in dental condition and long-term treatment processes. Some participants perceived that they had difficulties admitting their feelings/sensations associated with fear. In addition, the shame associated with the fear negatively affected the ability to deal with it: ˈ…when the time comes to start filling the teeth, that’s likely to be another pretty big stumbling blockˈ. Sedatives did not always give relief and severe reactions were considered as normal by the patients.

Discussion

The results showed that patients’ DF is a multifaceted phenomenon in terms of its emotional, behavioural, cognitive, and physiological components. In other words, each of these components appeared internally diverse when looked at from the point of view of the patients’ own perceptions in the frame of the diagnostic interview. Moreover, patients described the various contents of their DF in three different contexts: before, during and after dental treatment. Within the four components, 27 more categories of DF were identified depicting the various quality of emotions, behavioural adaptations, physiological reactions, or cognitions. In addition, 69 sub-categories or dimensions were identified.

Based on this study, patients with dental fear are capable of expressing, specifying, and analysing their fears in a versatile manner in the context of a diagnostic interview. The large number of categories and sub-categories and the related several contents of fear illuminated this. Our study differs from previous studies due to its theory-driven analysis of patients’ dental fear, as most of the previous related studies aim at developing models or theories [Citation23–26,Citation28]. By utilising the notion of the four components of fear as the basis of our theory-driven content analysis, we were able to show how the quality, intensity and duration of participants’ fears varied with respect to the context in which the fear was said to occur (before, during or after dental treatment). In addition, the analysis opened the door to better understanding of the origins of patients’ fears and factors related to alleviating or provoking fear. In summary, the approach used in this study broadened the comprehension related to the multifaceted nature of variations in patients’ dental fear that can be utilised in developing diagnostic practices for dentally anxious patients. For example, the IDAF-4C+ scale has been used successfully in Jönköping’s model of diagnosing patients’ fears [Citation34]. Dentists’ awareness of patients’ dental fear increased, and Jönköping’s model offered a holistic approach to the treatment of dental fear. We suggest that the diagnostic interview may offer a tool for dentists to gain a comprehensive and multifaceted picture of the patient’s dental fear.

Patients reported negative experiences related to dental treatment in the diagnostic interview. On the other hand, they also reflected on the ways and means that enabled them to cope with their fear, as has been discovered in previous studies [Citation25]. We noticed that the patients tried to do their best to cope with their fear, but while they were persuaded to adopt ideals learned, their challenges regarding maintaining acceptable thoughts and behaviours caused problems. A previous study showed ambivalence towards coping with dental fear and how one’s emotional state affected their daily routines and worsened their quality of life [Citation24]. The dentally anxious patients affected to stain alone with their problems in our study. If the participants had the possibility to talk about their experiences with a professional, it aided them to participate in dental care. Due to this, we propose that professionals should be initiative in reacting to a patient’s fear. Although, researchers have presented results indicating that dentists need to demonstrate sensitivity and delicacy when raising patients’ fears through treatment discussions [Citation28].

The dimensions related to cognitions revealed a few essential key characteristics regarding patients who suffer for dental fear. The first of them was lack of confidence, but other confounded psychologic disorders were also underlying aspects of fear, as stated in an earlier study [Citation35]. It has been confirmed that a new dentist can alleviate fear by using the iatrosedative process [Citation36] and when patients are calmed by the behaviour, attitude and communicative stance of a dentist, it helps patients with dental fear to build a trustful dentist-patient relationship [Citation37]. The second key was a patient’s ability to specify several fear-alleviating factors and the third key was the dentists’ attitudes towards accounting for patients’ worries and wishes. Empathy was positively associated with negotiated treatment plans, treatment adherence, increased patient satisfaction, and reduced dental anxiety in a review [Citation38]. It can be stated that a proper dentist-patient interaction is essential for the patient to maintain regular dental care visits. Study evidence showed that dentists learned to treat fearful patients over years of experience and regardless of other remaining competency challenges [Citation39] and most patients continued to have a complicated relation with dental care even after behavioural cognitive therapy [Citation26]. Further education for dentists who are interested in developing their skills in treating dentally anxious patients could alleviate stress related to treatment of patients with dental fear.

Fear of pain, lack of knowledge, feelings of loneliness were usual complaints and sources of stress experienced by patients in this study. A harmful consequence of the fear was the patients’ difficulties in talking about the sensitive topic and they used different non-verbal expressions or euphemism for fear during their interviews. One explanation for this could be embarrassment, shame, or guilt because of deterioration in oral health, as stated earlier [Citation40], but the meaning of non-verbal expressions requires further studies. Another reason for difficulties in admitting the sensations of fear could be the mindset to be strong, which can lead to patients tending to hide their fear and thus create negative thoughts. Regardless, the expressions patients used when reflecting on their experiences may be more meaningful than we were able to predict. For example, the deepest fears related to dental treatment were associated with a perceived threat to the person’s life, however the patients avoided talking about death. Thus, some patients may benefit from interventions with professionals who can help the patient deal with the difficult sensations and to correct false impressions.

We chose the qualitative research approach to gain a better understanding of the so far under-studied issue of DF – the patient’s own views about their dental fear in the frame of a diagnostic interview. The qualitative research on dental fear is currently characterised by highly inductive research designs involving the use of grounded theory methods. However, qualitative research designs informed by theoretical concepts can be useful to sensitise researchers to relevant issues, processes, and interpretations that they might not necessarily identify using purely inductive methods [Citation41]. We acknowledge that our decision to utilise four components of DF as the broad framework of analysis offers one possible approach to investigate people’s own perceptions of their DF. Possibly, some other aspects of DF may be recognised by using different theoretical and methodical approaches. However, given that the notion of the four components of DF had not been utilised in qualitative research on dental fear at the time of our study, it was meaningful to test it against the themes that emerged from the data. The analysis conducted with few interviews enabled us to make visible the multifaceted nature of DF as it is experienced by patients themselves, which speaks for the usefulness of the chosen method. In summary, our study sheds new light on the phenomenon that has so far been well recognised in everyday dental practice but very little studied, especially from a qualitative point of view. Although generalisation to all patients with dental fear cannot be made due to the relatively small data, the detailed analysis of a few individuals' perceptions enables identifying key aspects of the phenomenon under investigation and, therefore, developing generalisations to theoretical propositions [Citation42]. We suggest that the results gained in this study may well enhance the understanding of dental fear, especially when considered in terms of relatively similar contexts and groups of dentally anxious patients. Moreover, the outcome of this study may facilitate further and complementary analysis using the same or alternative theories and methods in the future.

The validity of the study can be evaluated through acceptable quality criteria of qualitative inquiry. To facilitate repeatability of the study, we have described the data collection and the process of analysis in detail. We suggest that credibility was reached because participants represented typical cases of dentally anxious patients in dental offices; the dentists recruited those who had difficulties coping with dental treatment and their fear level was measured using a self-report scale. We have aimed to ensure the reliability of the study by using researcher triangulation, i.e. two researchers read the emergent themes and independently coded the data. Moreover, we have provided data excerpts that cover all interviews through the analysis section to make sure that the reader has a possibility to evaluate our line of interpretation.

Conclusions

The results indicate that dental care professionals may gain comprehensive information about their patients’ DF by means of four component-based diagnostic interviews. This helps them to better identify and encounter patients in need of fear-sensitive dental care.

Acknowledgements

Ethical permission for this study was granted by The Hospital District of Northern Savo under the registration number: 281/13.02.00/2016. The authors complied with the instructions of the Finnish National Board on Research integrity regarding all ethical rules and participants’ rights in this study. The authors are grateful to the General Dental Practitioners and patients who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study and have nothing to disclose in connection to this study.

Data availability statement

The data set and analysis material used in this study are reserved at the University of Eastern Finland (UEF) in databases for researchers:\\research.uefad.uef.fi\groups by the name ˈpelkotutkimusˈ and on memory sticks saved in researcher rooms’ locked boxes. Please contact the first author for data set questions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Liinavuori A, Tolvanen M, Pohjola V, et al. Changes in dental fear among Finnish adults: a national survey. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44(2):128–134.

- Svensson L, Hakeberg M, Boman UW. Dental anxiety, concomitant factors and change in prevalence over 50 years. Community Dent Health. 2016;33(2):121–126.

- Berggren U, Meynert G. Dental fear and avoidance: causes, symptoms, and consequences. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109(2):247–251.

- Armfield JM. What goes around comes around: revisiting the hypothesized vicious cycle of dental fear and avoidance. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41(3):279–287.

- Cohen SM, Fiske J, Newton JT. The impact of dental anxiety on daily living. Br Dent J. 2000;189(7):385–390.

- De Jongh A, Schutjes M, Aartman IH. A test of Berggren's model of dental fear and anxiety. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119(5):361–365.

- Brahm CO, Lundgren J, Carlsson SG, et al. Dentists’ views on fearful patients. Problems and promises. Swed Dent J. 2012;36(2):79–89.

- Dailey YM, Humphris GM, Lennon MA. Reducing patients’ state anxiety in general dental practice: a randomized controlled trial. J Dent Res. 2002;81(5):319–322.

- Dailey YM, Humphris GM, Lennon MA. The use of dental anxiety questionnaires: a survey of a group of UK dental practitioners. Br Dent J. 2001;190(8):450–453.

- Neverlien PO. Assessment of a single-item dental anxiety question. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990;48(6):365–369.

- Viinikangas A, Lahti S, Yuan S, et al. Evaluating a single dental anxiety question in Finnish adults. Acta Odontol Scand. 2007;65(4):236–240.

- Milgrom P, Weinstein P. Dental fears in general practice: new guidelines for assessment and treatment. Int Dent J. 1993;43(3 Suppl 1):288–293.

- Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health. 1995;12(3):143–150.

- Humphris GM, Freeman R, Campbell J, et al. Further evidence for the reliability and validity of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale. Int Dent J. 2000;50(6):367–370.

- Armfield JM. How do we measure dental fear and what are we measuring anyway? Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010;8(2):107–115.

- Armfield JM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear (IDAF-4C+). Psychol Assess. 2010;22(2):279–287.

- Milgrom P, Weinstein P, Getz T. Treating fearful dental patients: a patient management handbook. 3rd ed. Seattle (WA): Dental Behavioral Resources; 2009.

- Vrana S, McNeil DW, McGlynn FD. A structured interview for assessing dental fear. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1986;17(3):175–178.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Wide Boman U, Carlsson V, Westin M, et al. Psychological treatment of dental anxiety among adults: a systematic review. Eur J Oral Sci. 2013;121(3 Pt 2):225–234.

- Kurki P, Honkalampi K, Korhonen M, et al. Kognitiivisen käyttäytymisterapian vaikuttavuus hammashoitopelon hoidossa aikuisilla [The effect of cognitive behavior therapy on dental anxiety among adults]. Finn Dent J. 2019;26(5):28–37. Finnish

- Friedman N, Cecchini JJ, Wexler M, et al. A dentist oriented fear reduction technique: the iatrosedative process. Compendium. 1989;10(2):113–118.

- Abrahamsson KH, Berggren U, Hallberg L, et al. Dental phobic patients' view of dental anxiety and experiences in dental care: a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2002;16(2):188–196.

- Abrahamsson KH, Berggren U, Hallberg LR, et al. Ambivalence in coping with dental fear and avoidance: a qualitative study. J Health Psychol. 2002;7(6):653–664.

- Bernson JM, Hallberg LR, Elfstrom ML, et al. 'Making dental care possible: a mutual affair': a grounded theory relating to adult patients with dental fear and regular dental treatment. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119(5):373–380.

- Morhed Hultvall M, Lundgren J, Gabre P. Factors of importance to maintaining regular dental care after a behavioural intervention for adults with dental fear: a qualitative study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68(6):335–343.

- Wang MC, Vinall-Collier K, Csikar J, et al. A qualitative study of patients' views of techniques to reduce dental anxiety. J Dent. 2017;66:45–51.

- Kulich KR, Berggren U, Hallberg LR. Model of the dentist-patient consultation in a clinic specializing in the treatment of dental phobic patients: a qualitative study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2000;58(2):63–71.

- Kulich KR, Berggren U, Hallberg LR. A qualitative analysis of patient-centered dentistry in consultations with dental phobic patients. J Health Commun. 2003;8(2):171–187.

- Tolvanen M, Puijola K, Armfield JM, et al. Translation and validation of the Finnish version of Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear (IDAF-4C+) among dental students. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17(1):85

- Öst L, Skaret E. Cognitive behavioral therapy for dental phobia and anxiety. Chichester (UK): Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

- King K, Humphris GM. Evidence to confirm the cut‐off for screening dental phobia using the Modified dental Anxiety Scale. Soc Sci Dentistry. 2010;1:21–28.

- Marks D, Yardley L. Research methods for clinical and health psychology. London: SAGE; 2004.

- Brahm CO, Lundgren J, Carlsson SG, et al. Development and evaluation of the Jönköping dental fear coping model: a health professional perspective. Acta Odontol Scand. 2018;76(5):320–330.

- Taneja P. Iatrosedation: a holistic tool in the armamentarium of anxiety control. SAAD Dig. 2015;31:23–25.

- Kani E, Asimakopoulou K, Daly B, et al. Characteristics of patients attending for cognitive behavioural therapy at one UK specialist unit for dental phobia and outcomes of treatment. Br Dent J. 2015;219(10):501–506.

- Friedman N. Fear reduction with the iatrosedative process. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1993;21(3):41–44.

- Jones LM, Huggins TJ. Empathy in the dentist-patient relationship: review and application. N Z Dent J. 2014;110(3):98–104.

- Gyllensvärd K, Qvarnström M, Wolf E. The dentist's care-taking perspective of dental fear patients - a continuous and changing challenge. J Oral Rehabil. 2016;43(8):598–607.

- Moore R, Brødsgaard I, Rosenberg N. The contribution of embarrassment to phobic dental anxiety: a qualitative research study. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:10–10.

- Macfarlane A, O'Reilly-de Brún M. Using a theory-driven conceptual framework in qualitative health research. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(5):607–618.

- Radley A, Chamberlain K. Health psychology and the study of the case: from method to analytic concern. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(3):321–332.