Abstract

Objective

The aim of this integrative review was to describe salutogenic factors associated with oral health outcomes in older people, from the theoretical perspectives of Antonovsky and Lalonde.

Material and methods

This study was based on a primary selection of 10,016 articles. To organize reported salutogenic factors, the Lalonde health field concept and Antonovsky’s salutogenic theory were cross tabulated.

Results

The final analysis was based on 58 studies. The following oral health outcome variables were reported: remaining teeth, caries, periodontal disease, oral function and oral health related quality of life (OHRQoL). We could identify 77 salutogenic factors for oral health and OHRQoL. Salutogenic factors were identified primarily within the fields of Human Biology (such as ‘higher saliva flow’, ‘BMI < 30 kg/m2’ and ‘higher cognitive ability at age 11’), Lifestyle (such as ‘higher education level’, ‘social network diversity’ and ‘optimal oral health behaviour’) and Environment (such as ‘lower income inequality’, ‘public water fluoridation’ and ‘higher neighbourhood education level’). In the age group 60 years and over, there was a lack of studies with specific reference to salutogenic factors.

Conclusions

The results provide an overview of salutogenic factors for oral health from two theoretical perspectives. The method allowed concomitant disclosure of both theoretical perspectives and examination of their congruence. Further hypothesis-driven research is needed to understand how elderly people can best maintain good oral health.

Introduction

General health and associated oral health conditions have a direct influence on the quality of life and lifestyle of older people with respect to impaired eating, social appearance and communication [Citation1,Citation2]. The associations between periodontal disease and general health conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes have been confirmed and conversely the association between unhealthy lifestyle and increased risk of most common dental diseases, such as dental caries and periodontal disease [Citation3,Citation4].

Despite some overall positive trends towards improved dental status in the elderly, such as retention of a functional dentition [Citation5,Citation6], there is evidence of profound disparities in dental status among older people across and within countries [Citation7]. However, there is no adequate biological explanation for these disparities: various oral conditions can be effectively prevented and controlled, through a combination of community, professional and individual effort [Citation8]. The upstream key determinants of the health of individuals and populations are the circumstances in which people are born, grow-up, live, work and age. These circumstances are to a large extent shaped by economics, social policies, cultural capital and education. Thus widespread ill health and disease are considered to be attributable to a combination of poor social support, low educational level and unequal socio-economic preconditions [Citation9–12].

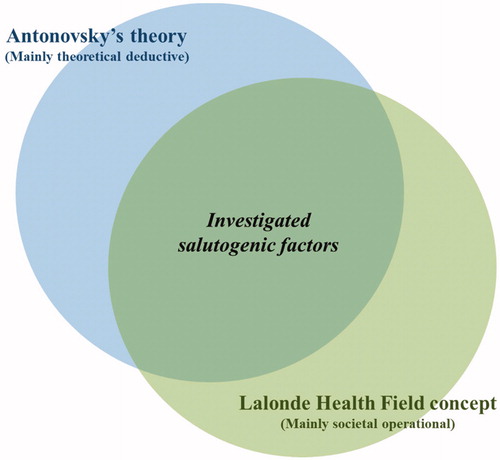

This article explores multiple factors influencing the oral health of older people from a salutogenic perspective, combining individual and structural societal levels in the analysis. We based our analysis on reading the searched literature and identifying salutogenic factors from the perspectives of two current theories on salutogenesis (according to Antonovsky and Lalonde, see below) that overlap and complement each other ().

Figure 1. Illustration of a preconception of the overlapping of Antonovsky’s theory and the Lalonde Health Field concept, for the review of articles on salutogenesis.

Salutogenesis as a concept

In contrast to the prevailing pathogenic paradigm, salutogenesis was proposed by Antonovsky as a concept of health and wellbeing. He stated that pathogenesis has preoccupied us to the extent that the focus is on disease, not only with respect to diagnosis and treatment, but also with respect to aetiology and prevention. As an alternative approach, Antonovsky emphasized the importance of focussing on people’s resources and their capacity to maintain health rather than the traditional focus on disease, illness and risk factors [Citation10,Citation13].

According to Antonovsky’s theory, health can be seen as a movement on a continuum, between total absence of health and complete health. A dynamic interaction is proposed between health and disease, meaning that even if affected by disease a person can, to some extent, still be relatively healthy. Antonovsky introduced two interconnected core elements essential for the salutogenic theory: the sense of coherence (SoC) and the generalized resistance resources (GRR). The SoC is the ability to identify and use one’s own health resources. It reflects a person’s view of life and capacity to respond to stressful situations and has three components: comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness [Citation10]. The GRR concept identifies resources available to enable the movement towards health, or to maintain good health, and includes a range of resources, e.g. knowledge, money, social support and cultural capital [Citation10–12]. For the purpose of this article, we chose to refer to GRRs as ‘salutogenic factors’. These are factors which on the basis of epidemiological evidence, are known to promote, strengthen and maintain oral health in older people [Citation12,Citation13].

Salutogenic factors promote a strong SoC [Citation10]. A strong SoC seems to some extent to promote healthy aging [Citation14]. This is of value not only to the individual but also to society at large: older people are an important social and economic resource and if an extended lifespan comprises more years of health this not only enhances their individual quality of life, but also offers an opportunity to make a greater contribution to society [Citation13,Citation14].

Previous research on salutogenesis

The concept of salutogenesis has been the subject of research in different fields for nearly half a century. This research has generated a number of papers, primarily within public health and health promotion but also in education, nursing, social work and psychology. With respect to oral health, however, few publications are to be found. For example, recent research suggests positive associations between a strong SoC and oral and general health behaviours [Citation15,Citation16], as well as knowledge of and attitudes towards oral health [Citation17]. Similarly, the availability of social support and financial security has been shown to have a positive impact on the oral health of older people [Citation18,Citation19]. With respect to oral health in older people, however, to our knowledge, there are no studies explicitly applying the salutogenic factors or SoC concept to oral health outcome measures and to date no review has been undertaken of associated salutogenic factors.

Antonovsky made a novel contribution to the understanding of salutogenesis as a combination of individual situational factors and factors related to structural factors on a societal level. Yet, in most of the studies that have used the salutogenic framework, the main focus has been on researching individual salutogenic factors rather than structural/societal factors. Our understanding of the unique contribution of Lalonde is that he made a clearer emphasis on the operational perspective in a hierarchical multi-level structure for salutogenic factors and health. The two perspectives of the same phenomenon suggest two operational dimensions that support each other, and if viewed together, could provide a frame for understanding salutogenesis. Also, such an approach could be used for analysis of empirical data of salutogenic factors.

The Lalonde health field concept

As Minister of National Health and Welfare in Canada in 1974, Lalonde utilized this social perspective to try to identify factors of causal importance for the maintenance of health. Lalonde’s primary interest was ‘to unfold a new perspective on the health of Canadians and to thereby stimulate interest and discussion on future health programs for Canada […]. These problems cannot be solved solely by providing health services but rather must be attacked by offering the Canadian people protection, information and services through which they will themselves become partners with health professionals in the preservation and enhancement of their vitality’ [Citation20].

The Lalonde health field concept was developed to provide a wider conceptual framework for understanding causal factors relevant to health. The concept points out that determinants of health go beyond traditional medical care, and that health is also strongly supported by complex relationships between the individual and society [Citation20]. Lalonde identified four principal components of the health field: human biology, environment, lifestyle and health care organization. These four components were considered to be interdependent, with dynamic interactions over the course of a lifetime, determining the level of health and well-being achieved by an individual [Citation20].

Antonovsky and Lalonde present different operational perspectives on health and health behaviour. They both highlight complex relationships between the individual and society and emphasize the responsibility of society to create conditions which enable individuals to make healthy choices and maintain their health. Combining these different perspectives connects the individual and society and might help to understand factors which influence the oral health of the elderly. More specifically, connecting different theoretical perspectives can offer a basis for constructing theory-driven empirical studies intended to identify as yet unknown resource factors for oral health. This in turn can direct both research and implementation to focus on salutogenic factors, with important practical implications for health care and policy makers. It could also identify topics which warrant further research, as it offers the potential for formulation of a number of hypotheses, linking individual and society, which can be tested empirically.

Thus, our preconception was that Antonovsky had primarily given a theoretical underpinning for research on salutogenesis primarily on factors on an individual level. Lalonde’s contribution was more directed to an operational perspective on a societal level. However, both theories overlap to a substantial degree. This overlapping became apparent after categorizing articles reviewed according to these two theories.

The initial purpose of this study was to analyse published data from a salutogenic perspective. However, during the literature search, it became clear that research on oral health (of the elderly) has traditionally had a strictly pathogenic approach.

Aim

The aim of this integrative review was to describe, comprehensively, salutogenic factors reportedly associated with oral health and oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), in older people. Two theoretical perspectives are considered as common themes, Antonovsky’s salutogenic theory and the Lalonde heath field concept. The study is intended to describe how the GGRs operate/occur within and between the Lalonde health fields.

The research objectives were

To study whether two theoretical perspectives on salutogenesis could coherently reflect empirical data in the literature. The oral health outcomes are proxies for assessing the effects of salutogenic factors.

To identify common factors for oral health of relevance for understanding health promotion, by combining two theoretical perspectives.

To identify health fields poorly explored in the literature.

Material and method

Design

This study was conducted as an integrative review, using a modification of Cooper’s framework, as presented by Whittemore and Knafl [Citation21–23]. This review method allows data from different types of research designs to be combined and includes empirical as well as theoretical literature, in order to provide an understanding of the phenomenon of interest [Citation23,Citation24], in this case, oral health of the elderly. Creswell et al. define mixed methods and methodology as: research that calls for real-life contextual understandings, multi-level perspectives and cultural sensitivity; quantifying magnitudes as well as exploring the meaning of constructs; using multiple methods (e.g. intervention trials and interviews); and intentionally integrating methods to draw on the strengths of each [Citation25].

Key stages in this approach include problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation. This method was chosen for the purpose of selecting previous primary research without any limitations on research designs. A quality assessment procedure was used for this purpose. More details on method and quality assessment are provided in Supplementary Appendices B and C.

Problem identification

Cooper [Citation21,Citation22] suggests that the data available on a particular topic can be organized by applying a theoretical model, as it will help to operationalize variables and extract appropriate data from primary sources [Citation23]. The starting point for this review was Antonovsky’s salutogenic theory and the Lalonde health field concept with reference to oral health in the elderly [Citation10,Citation20]. Both theories have a salutogenic approach. Thus, identifying similarities between their perspectives should help in understanding factors influencing oral health among the elderly. Our preconception was that the GRRs are the actual salutogenic factors operating within and among the individual health fields.

Conceptual definitions and outcome measures

Lalonde’s and Antonovsky’s frameworks offer a structure for the understanding of the contemporary issues of health which may assist in the identification of salutogenic factors for oral health in older people. Conceptual definitions of the health fields and the GRR domains are described in and Citation2, respectively. Oral health outcome variables were remaining teeth, caries, periodontal disease and oral function. Furthermore, the oral health outcomes and OHRQoL were to be regarded as proxies for the effects of the salutogenic factors.

Table 1. Health field (Lalonde) components for salutogenic factors and their conceptual definitions for oral health in older people.

Table 2. Generalized resistance resources (GRR) and their conceptual definitions according to Antonovsky.

Salutogenic factors for oral health were conceptualized as factors which on the basis of epidemiological evidence, are known to promote, strengthen and maintain oral health in older people [Citation10,Citation11]. These salutogenic factors occurred within and between health fields and are described in more detail in and Citation2.

Literature search

In order to identify salutogenic factors associated with oral health in older people, a search was conducted during February 2020 for peer-reviewed empirical studies published in English, without any time restrictions. The following electronic databases were searched: PubMed, Scopus (Health Science and Social Science and Humanities subject areas), CINAHL Plus with full text via EBSCO and ProQuest (Health and Medicine subject area). The search string included such terms as ‘oral health’, ‘oral health related quality of life’, ‘salutogenesis’, ‘protective factors’ and ‘health resources’. Details of the search are presented in Supplementary Appendices B and C. An ancestry search and a descendancy search were undertaken [Citation22].

Screening

For this review, titles and abstracts were screened for variable applicability using the selection criteria shown in [Citation26,Citation27]. The inclusion criteria were primary research combined with methodological and/or theoretical manuscripts, study population ≥60 years, oral health context and oral health indicators and published in English. Articles were excluded if the study population was <60 years or if it was impossible to extract data for people ≥60 from the publication. Abstracts, conference proceedings, and editorials were also excluded from the review. Older people (the elderly) were defined as aged 60 years and older, in accordance with the United Nation’s agreed cut-off point for the older population [Citation28].

Table 3. Selection criteria for this integrative review.

Potentially relevant abstracts were retained for further evaluation in full-text format, using a coding guide [Citation22].

Data evaluation

The final sample for this integrative review included observational methods: cross-sectional, cohort and longitudinal. Quality scores based on several risks of bias were calculated and incorporated into the analysis [Citation23,Citation29]. Three additional questions about conflict of interest were added [Citation30], using in total 17 criteria.

Quality assessment of each study was transformed into a quality score, in order to allow subsequent evaluation of intervening factors in the data analysis. All relevant articles from the literature search were scored for quality, as shown in Supplementary Appendix C. These articles fulfilled more than 40% of the quality criteria. The final quality score was based on quality of study regardless of epistemological approach. The details are provided in Supplementary Appendices B and C.

Data analysis

Data were collected and sorted strictly according to the terminologies and concepts used by the authors of the original papers. We followed a data analysis sequence: data reduction, data display, data comparison, drawing conclusions and verification [Citation23].

Similar variables from several original articles were compiled under one heading. For example, independent variables ‘higher education level’, ‘education highest quartile’, ‘education 16 years or more’ from original articles that were positively related to better clinical oral health outcomes were pooled and defined as a salutogenic factor ‘higher educational level’ for better oral health.

The similarities between the theories became obvious during the analysis and we choose to visualize this by cross-tabulation to enhance patterns and relationships within and across primary data sources. Thus, we constructed a data spreadsheet which displayed statistically significant relationships (as reported in the original publications) between a factor and an oral health-related outcome [Citation23].

We limited the outcome measures to two main categories, clinical oral health and OHRQoL, one focussing on the traditional perspective of disease, the other the assessment of quality of life, made by the respondent. This reflects a traditional way of assessing health and disease, one from the caregiver’s perspective and the other from the patient’s perspective. Each health field factor was categorized as having either a positive or a negative correlation with oral health and OHRQoL.

Further analysis involved examining the data in spreadsheets with the outcome measures oral health and OHRQoL, respectively, and identifying patterns for organizing data into a suitable framework [Citation23]. Then, we clustered related health salutogenic factors to facilitate interpretation. For example, the salutogenic factor ‘optimal oral hygiene behaviour’ included such factors from original publications as ‘brushing twice a day or more’, ‘brushing time 3 min or more’, ‘use of dental floss or interdental brushes’ and ‘use of fluoridated toothpaste’. Similarly, we sorted those factors according to Lalonde’s framework, in relation to Antonovsky’s salutogenic factors. Cross-tabulation clearly revealed conceptual similarities between the frameworks. It resulted in a useful and clear combination of Antonovsky’s and Lalonde’s frameworks.

Detailed information on the literature search, screening, data evaluation and data analysis are provided in Supplementary Appendix B.

Results

Result of the search

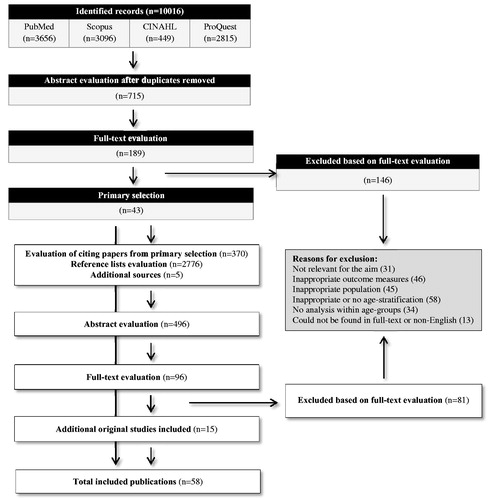

The literature search produced a total of 10,016 records and 189 unique articles were selected for evaluation in full-text. Of these, 43 studies met the inclusion criteria. An ancestry and descendancy search identified a further 15 studies. Thus, 58 studies were included in the final sample for analysis ().

Figure 2. A flow chart of search results and reasons for exclusion after full text evaluation is presented. The papers in the primary selection were scrutinized for citations, and the references in citing articles as well as in the primary selection were then evaluated.

The included studies () were published between 1987 and 2019 and were conducted in countries located in all regions of the world, except Africa. Thirty-eight studies examined the associations of related factors with clinical oral health outcomes, 18 focussed on OHRQoL and 2 concerned associations with both clinical oral health and OHRQoL outcomes.

Table 4. Geographical distribution of studies included in the analysis using the integrative review.

No study was found which explicitly examined the salutogenic factors or SoC concepts among older people, with reference to the outcome measures of interest.

Cross-table analysis

Salutogenic factors related to oral health

The result demonstrated that associations with better oral health among the elderly involved three health fields and nine salutogenic domains (). No associations were found within the field of Health Care Organization or within the macrosociocultural domain.

Table 5. Cross-tabulation of reported factors significantly associated with better oral health among people ≥60 years, sorted according to the Antonovsky Salutogenic model and the Lalonde Health Field concept. The brackets show number of articles for each factor.

Several salutogenic factors were linked to the reported clinical oral health outcome variables (remaining teeth, caries, periodontal disease and oral function). Salutogenic factors related to both the health field of human biology and the genetic and constitutional domains, were identified. The Physical domain included the following reported factors: younger old age [Citation31,Citation32], male sex [Citation33,Citation34], being nulliparous [Citation35], no history of diabetes [Citation36,Citation37] systolic blood pressure <140 mmHg [Citation38], BMI < 30 kg/m2 [Citation38] and better physical function [Citation39]. There was conflicting evidence regarding increased BMI in men [Citation40]. Men with a high BMI had a significantly lower risk of having 19 or fewer teeth. Several biomarkers were reported to have a positive association with better oral health: higher salivary flow [Citation41,Citation42], higher blood albumin levels [Citation40], higher S-urea concentration [Citation43], lower concentration of fB-Glucose [Citation44] and lower concentration of S-urate [Citation44], longer duration of oestrogen use [Citation45], fasting blood sugar <110 mg/dl [Citation38] as well as HDL-C < 40 mg/dl [Citation38]. Higher intellect [Citation46] and higher cognitive ability at age 11 [Citation46] were related to the human biology health field and the knowledge-intelligence domain.

The most frequently found salutogenic factors were related to the lifestyle health field. One factor was found within physical domain – light salt use [Citation37,Citation38]. Several identified factors were related to both the lifestyle health field and the psychosocial domains [Citation33,Citation36,Citation39,Citation41,Citation46–57]. The Preventive health orientation domain comprised a large number of factors as well as conflicting evidence [Citation34,Citation36–40,Citation43,Citation49,Citation52–54,Citation56,Citation58–67].

We found a small number of studies within the preventive health orientation domain, reporting correlations inconsistent with the generally accepted opinion. These inconsistencies were related to three factors: dental attendance, alcohol consumption and smoking [Citation40,Citation54,Citation68,Citation69].

The environment health field interacted with the artifactual-material and the cognitive domains [Citation56,Citation57] as well as the interpersonal-relational and Preventive health orientation domains [Citation36,Citation46,Citation48,Citation58,Citation65,Citation70]. Two factors were found within the preventive health orientation – mother did not prefer sweet food [Citation66] and public water fluoridation [Citation57]. No conflicting evidence was observed.

One salutogenic factor related to the Health Care Organization field, was found within the Preventive health orientation – higher availability and ease of access to oral health services [Citation57].

Salutogenic factors related to oral health-related quality of life

The results disclosed fewer reports of associations between salutogenic factors and better OHRQoL than for oral health (). No salutogenic factors were found in the intersections between the Health Care Organization health field and any of the domains. Identified salutogenic factors, related to the health field of Human Biology, were found only within the physical domain [Citation71–76]. We observed conflicting evidence regarding older age and the use of full upper and lower dentures [Citation77,Citation78]. The Lifestyle health field comprised one salutogenic factor within several domains [Citation58,Citation59,Citation72,Citation73,Citation75–77,Citation79–86] as well as several factors within the Preventive Health Orientation [Citation63,Citation64,Citation81,Citation82,Citation85–89]. Inconsistency was observed in one study [Citation71].

Table 6. Cross-tabulation of reported factors significantly associated with better Oral Health Related Quality of Life among people ≥60 years, sorted according to the Antonovsky Salutogenic model and the Lalonde Health Field concept. The brackets show number of articles for each factor.

The Environment health field was associated with four psychosocial domains, including the following salutogenic factors: lower income inequality [Citation87] within the artifactual-material; longest duration of administrative jobs for men [Citation88] within the Cognitive; having easy access to dental care [Citation58] and living in municipalities with a lower density of dentists [Citation88], all within the Interpersonal-relational; native-born and longer-term immigrants [Citation73] within the Macrosociocultural. Inconsistent associations were disclosed for the factor ‘living in municipalities with a lower density of dentists’ [Citation88].

Discussion

The main result was that several factors could be associated with better oral health and better OHRQoL. However, these factors were identified within a minority of the intersections in the cross-tables ( and ). Another important finding was the successful combination of Antonovsky’s salutogenic theory and the Lalonde health field concept, coherently identifying common factors of relevance to oral health promotion. Third, the results identified significant knowledge gaps, which should be addressed in future research. Finally, there seemed to be a lack of hypothesis-driven research in the salutogenic research area.

The salutogenic factors relating to the health field of human biology were found to be clustered mainly in the Physical and Biochemical domains. They were related to age, sex and physical function (including cognitive function from the psychosocial domains). Salutogenic factors relating to the health field of Lifestyle (situational components) were clustered around the psychosocial domains and included factors such as income, education, self-awareness and attitude to health, family conditions and leisure activity. Several factors were also clustered in the Preventive health orientation domain, such as regular dental attendance, alcohol consumption and tobacco habits and physical activity. Salutogenic factors related to the environment health field (structural components) were clustered under interpersonal-relational domain, such as social class, educational level, access to dental care and friendship networks.

In all, the search identified only one study [Citation66] applying Antonovsky’s framework in its design. A few studies included in the final sample were intended to examine factors critical for tooth retention, retention of functional dentition and positive OHRQoL [Citation34,Citation45,Citation52,Citation75]. The remainder of the sample included studies with an initial pathogenic perspective. Most notable was the absence of research data on salutogenic factors associated with oral health and OHRQoL outcomes within the Health Care Organization field, despite the fact that considerable community effort and significant resources are directed to healthcare organization [Citation20,Citation89,Citation90].

Our results indicated an extensive global distribution of research. There were a greater number of reviewed studies conducted in countries with rapidly increasing numbers of elderly in their populations (e.g. Japan, the Nordic countries and Brazil). Also, there is a definitive lack of studies in Africa.

The initial purpose of this study was to analyse data from a salutogenic perspective. However, it became clear that research on oral health had a strictly pathogenic approach. In spite of the lack of explicit salutogenic design in the research reviewed, a number of such factors could be identified. For almost every such case the relationship of singular factors to the two outcome measures was logically consistent and in accordance with the theoretical frameworks. The few instances of discrepancies could be understood as logical in their specific cultural context.

Another important finding was that the cross-tabulation of Antonovsky’s salutogenic theory and the Lalonde health field concept confirmed that these two theories complement each other, based on a similar understanding of the mechanisms underlying the interaction of salutogenic factors associated with oral health and OHRQoL outcomes. The analysis supported our preconception that the salutogenic factors in the GRR domains are operating within and between separate health fields.

An earlier attempt has been made to partly combine a theoretical framework with Antonovsky’s salutogenic theory. Riedel et al. combined elements from the Berry Acculturation model and Antonovsky’s theory [Citation91], but not in relation to empirical data. The authors argued that the combined model offered a better explanation of the controversial findings and allowed the formulation of new hypotheses in the migrant health area of research. Likewise, combining the two theoretical frameworks offers a structure for future hypothesis-driven research in the field of oral health. It could facilitate the analysis of previously non-explored associations between potentially salutogenic factors and measures of oral health identified by using empirical data, as studying the associations between potential salutogenic factors (e.g. self-perceived treatment need, confidence in maintaining good oral health, clinic’s recall system) and selected measures of oral health among elderly people (e.g. number of remaining sound teeth and OHRQoL).

By using the method of theory triangulation [Citation92], we searched for regularities in the collected data by crosschecking reported factors from two different theoretical frameworks. According to Patton, ‘studies based on only one method are more vulnerable to errors linked to that particular method […] than those applying multiple methods, in which different types of data provide cross-data validity checks’ [Citation92]. Thus, as well as raising the quality level of this review, we were able to provide a more detailed and balanced view of knowledge in the area. Our approach to exploring the complex evidence might add a new perspective to oral health research. Moreover, it highlights the empty cells intersecting the two concepts in relation to outcome variables, disclosing lack of knowledge and indicating a topic for future research. We conclude that triangulation is also a useful tool for verifying a deeper understanding of salutogenesis.

Knowledge of oral health research gained by using this method, including cross-tabulation of the findings, can have implications for accessing data for promotion of oral health. This approach might also be used for strategies which facilitate resources at individual and contextual level for the elderly, including determining priorities and allocating resources which enable the maintenance of good oral health.

Furthermore, one of the benefits of mixed methods research is to bridge research methods with different goals, strengths and limits [Citation25]. The results disclosed that there are few published studies examining the association between salutogenic factors and oral health in the elderly. Therefore, the synthesis also included studies which examined the association between certain factors and the absence of oral disease. However, as Sheiham [Citation93] proposed, ‘contemporary concepts of health suggest that oral health should be defined in general physical, psychological and social well-being terms in relation to oral status’. This aspect was reflected by using OHRQoL measures and a consistent pattern emerged of association for the two outcome measures, oral health and OHRQoL. Unfortunately, the search revealed fewer studies reporting salutogenic factors associated with OHRQoL outcomes.

Limitations

There is an inherent risk for publication bias as this review focussed solely on published reports in journals, excluding e.g. monographic dissertations or ‘grey’ literature. This review excluded non-English publications and some possibly relevant research reported in other languages [Citation94].

The methodology used in the reviewed reports demonstrated mainly a quantitative approach and descriptive design. Few studies examined the causal relationships between associated concepts. Obviously, there is a lack of hypothesis-driven and prospective research. However, this limitation applies to all open system sociological research [Citation95] and may indicate that this research area is in its early phase of development.

Another possible limitation of this review is the predominant use of the ‘absence of disease’ as a proxy for health in a salutogenic perspective in the studies retrieved. This issue was addressed by using two outcome measures, one focussing on the traditional perspective of disease, the other the respondent’s perception of quality of life.

Recommendations for future research

Future research should be focussed on analyses aiming to identify salutogenic factors in prospective studies based on hypotheses generated from empirical facts and theory. Unresearched areas, as identified in our analysis, would be a focus for further research. Qualitative studies, as well as mixed method designs can be useful.

Conclusion

We have shown how specific salutogenic factors, within separate health fields, are related to reported better oral health clinical outcome variables and better OHRQoL. The successful combining of Antonovsky’s and Lalonde’s frameworks indicates that they are based on a similar understanding of underlying mechanisms for interaction of salutogenic factors associated with oral health and OHRQoL outcomes. However, few factors have been identified within a majority of health fields. The method of triangulation suggests a way of verifying a common understanding of salutogenesis. Moreover, despite nearly half a century of salutogenic research, the field of oral health research is only at an early stage of development. There is a need for consistency in the definition of outcome measures and hypothesis-driven research.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (78.4 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kandelman D, Petersen PE, Ueda H. Oral health, general health, and quality of life in older people. Spec Care Dentist. 2008;28(6):224–236.

- Oral Health in America. A report of the surgeon general. Rockville (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000.

- Dörfer C, Benz C, Aida J, et al. The relationship of oral health with general health and NCDs: a brief review. Int Dent J. 2017;67(2):14–18.

- Jepsen S, Blanco J, Buchalla W, et al. Prevention and control of dental caries and periodontal diseases at individual and population level: consensus report of group 3 of joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(18):S85–S93.

- Slade GD, Akinkugbe AA, Sanders AE. Projections of U.S. Edentulism prevalence following 5 decades of decline. J Dent Res. 2014;93(10):959–965.

- Sanders AE, Slade GD, Carter KD, et al. Trends in prevalence of complete tooth loss among Australians, 1979–2002. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28(6):549–554.

- Petersen PE, Yamamoto T. Improving the oral health of older people: the approach of the WHO global oral health programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(2):81–92.

- Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century-the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(1):3–23.

- Closing the Gap in a Generation. Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008.

- Antonovsky A. Health, stress and coping. 4th ed. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 1982.

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health. How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 1987.

- Lindström B, Eriksson M. A salutogenic approach to tackling health inequalities. In: Morgan A, Davies M, Ziglio E, editors. Health assets in a global context. Theory, methods, action. New York (NY): Springer; 2010.

- Antonovsky A. Some salutogenic words of wisdom to the conferees. Sweden: The Nordic School of Public Health in Gothenburg; 1993.

- Antonovsky A, Sagy S. Confronting developmental tasks in the retirement transition. Gerontologist. 1990;30(3):362–368.

- Savolainen J, Suominen-Taipale A, Uutela A, et al. Sense of coherence associates with oral and general health behaviours. Community Dent Health. 2009;26(4):197–203.

- Bernabe E, Kivimaki M, Tsakos G, et al. The relationship among sense of coherence, socio-economic status, and oral health-related behaviours among Finnish dentate adults. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117(4):413–418.

- Lindmark U, Hakeberg M, Hugoson A. Sense of coherence and oral health status in an adult Swedish population. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011;69(1):12–20.

- Ringland C, Taylor L, Bell J, et al. Demographic and socio-economic factors associated with dental health among older people in NSW. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28(1):53–61.

- Avlund K, Holm-Pedersen P, Morse DE, et al. Social relations as determinants of oral health among persons over the age of 80 years. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(6):454–462.

- Lalonde M. A new perspective on the health of Canadians. A working document. Ottawa, Canada: Government of Canada; 1974. p. 77.

- Cooper H. Synthesizing research: a guide for literature reviews. 3d ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1998.

- Cooper H. Research synthesis and meta-analysis: a step-by-step approach. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publication; 2010.

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–553.

- Whittemore R. Combining evidence in nursing research: methods and implications. Nurs Res. 2005;54(1):56–62.

- Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano, Clark VL, et al. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. Vol. 2013. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health; 2011. p. 541–545.

- Morton S, Levit L, Berg A, et al. Finding what works in health care: standards for systematic reviews. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2011.

- Mateen FJ, Oh J, Tergas AI, et al. Titles versus titles and abstracts for initial screening of articles for systematic reviews. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:89–95.

- Proposed working definition of an older person in Africa for the MDS project. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002.

- Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. Bethesda (MD): National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; 2014.

- Rosen M, editor. Assessment of methods in healthcare and medical care. A handbook. 2 ed. Mölnlycke, Sweden: Elanders Sverige AB; 2014.

- Oliveira TCd, Silva DAd, Freitas YNLd, et al. Socio-demographic factors and oral health conditions in the elderly: a population-based study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57(3):389–397.

- Mendes DC, Poswar FDO, de Oliveira MVM, et al. Analysis of socio-demographic and systemic health factors and the normative conditions of oral health care in a population of the Brazilian elderly. Gerodontology. 2012;29(2):e206–e214.

- Adams C, Slack-Smith LM, Larson A, et al. Edentulism and associated factors in people 60 years and over from urban, rural and remote Western Australia. Aust Dent J. 2003;48(1):10–14.

- Guiney H, Woods N, Whelton H, et al. Non-biological factors associated with tooth retention in Irish adults. Community Dent Health. 2011;28(1):53–59.

- Rundgren A, Osterberg T. Dental health and parity in three 70-year-old cohorts. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15(3):134–136.

- Aida J, Kuriyama S, Ohmori-Matsuda K, et al. The association between neighborhood social capital and self-reported dentate status in elderly Japanese-the Ohsaki Cohort 2006 Study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39(3):239–249.

- Kurahashi T, Kitagawa M, Matsukubo T. Factors associated with number of present teeth in adults in Japanese urban city. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2017;58(2):85–94.

- Kitagawa M, Kurahashi T, Matsukubo T. Relationship between general health, lifestyle, oral health, and periodontal disease in adults: a large cross-sectional study in Japan. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2017;58(1):1–8.

- Jette AM, Feldman HA, Tennstedt SL. Tobacco use: a modifiable risk factor for dental disease among the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(9):1271–1276.

- Ando A, Ohsawa M, Yaegashi Y, et al. Factors related to tooth loss among community-dwelling middle-aged and elderly Japanese men. J Epidemiol. 2013;23(4):301–306.

- De Marchi RJ, Hilgert JB, Hugo FN, et al. Four-year incidence and predictors of tooth loss among older adults in a southern Brazilian city. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40(5):396–405.

- De Marchi RJ, Dos Santos CM, Martins AB, et al. Four-year incidence and predictors of coronal caries in south Brazilian elderly. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43(5):452–460.

- Norlen P, Johansson I, Birkhed D. Impact of medical and life-style factors on number of teeth in 68-year-old men in southern Sweden. Acta Odontol Scand. 1996;54(1):66–74.

- Norlen P, Ostberg H, Bjorn AL. Relationship between general health, social factors and oral health in women at the age of retirement. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991;19(5):296–201.

- Krall EA, Dawson-Hughes B, Hannan MT, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen replacement and tooth retention. Am J Med. 1997;102(6):536–542.

- Mõttus R, Starr JM, Deary IJ. Predicting tooth loss in older age: interplay between personality and socioeconomic status. Health Psychol. 2013;32(2):223–226.

- Lin HC, Wong MC, Zhang HG, et al. Coronal and root caries in Southern Chinese adults. J Dent Res. 2001;80(5):1475–1479.

- McGrath C, Bedi R. Influences of social support on the oral health of older people in Britain. J Oral Rehabil. 2002;29(10):918–922.

- Vysniauskaite S, Kammona N, Vehkalahti MM. Number of teeth in relation to oral health behaviour in dentate elderly patients in Lithuania. Gerodontology. 2005;22(1):44–51.

- Osterberg T, Johanson C, Sundh V, et al. Secular trends of dental status in five 70-year-old cohorts between 1971 and 2001. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34(6):446–454.

- Colussi CF, de Freitas SF. Edentulousness and associated risk factors in a south Brazilian elderly population. Gerodontology. 2007;24(2):93–97.

- Thorstensson H, Johansson B. Why do some people lose teeth across their lifespan whereas others retain a functional dentition into very old age? Gerodontology. 2010;27(1):19–25.

- Holst D, Schuller AA. Oral health in a life-course: birth-cohorts from 1929 to 2006 in Norway. Community Dent Health. 2012;29(2):134–143.

- Shah N, Sundaram KR. Impact of socio-demographic variables, oral hygiene practices, oral habits and diet on dental caries experience of Indian elderly: a community-based study. Gerodontology. 2004;21(1):43–50.

- Tsakos G, Sabbah W, Chandola T, et al. Social relationships and oral health among adults aged 60 years or older. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(2):178–186.

- Aida J, Kondo K, Yamamoto T, et al. Is social network diversity associated with tooth loss among older Japanese adults? PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159970.

- Bomfim RA, Frias AC, Pannuti CM, et al. Socio-economic factors associated with periodontal conditions among Brazilian elderly people – Multilevel analysis of the SBSP-15 study. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206730.

- Astrom AN, Ekback G, Ordell S, et al. Long-term routine dental attendance: influence on tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life in Swedish older adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2014;42(5):460–469.

- Samnieng P, Ueno M, Zaitsu T, et al. The relationship between seven health practices and oral health status in community-dwelling elderly Thai. Gerodontology. 2013;30(4):254–261.

- Slade GD, Gansky SA, Spencer AJ. Two-year incidence of tooth loss among South Australians aged 60+ years. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25(6):429–437.

- Haikola B, Oikarinen K, Soderholm AL, et al. Prevalence of edentulousness and related factors among elderly Finns. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35(11):827–835.

- Jiang Y, Okoro CA, Oh J, et al. Sociodemographic and health-related risk factors associated with tooth loss among adults in Rhode Island. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:45.

- Yoshioka M, Hinode D, Yokoyama M, et al. Relationship between subjective oral health status and lifestyle in elderly people: a cross-sectional study in Japan. ISRN Dent. 2013;2013:687139.

- Gilbert GH, Duncan RP, Crandall LA, et al. Attitudinal and behavioral characteristics of older Floridians with tooth loss. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21(6):384–389.

- Corbet EF, Wong MC, Lin HC. Periodontal conditions in adult Southern Chinese. J Dent Res. 2001;80(5):1480–1485.

- Morita I, Nakagaki H, Kato K, et al. Salutogenic factors that may enhance lifelong oral health in an elderly Japanese population. Gerodontology. 2007;24(1):47–51.

- Yoshihara A, Watanabe R, Hanada N, et al. A longitudinal study of the relationship between diet intake and dental caries and periodontal disease in elderly Japanese subjects. Gerodontology. 2009;26(2):130–136.

- Hanioka T, Ojima M, Tanaka K, et al. Association of total tooth loss with smoking, drinking alcohol and nutrition in elderly Japanese: analysis of national database. Gerodontology. 2007;24(2):87–92.

- Dogan BG, Gokalp S. Tooth loss and edentulism in the Turkish elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(2):e162– e166.

- Takeuchi K, Aida J, Kondo K, et al. Social participation and dental health status among older Japanese adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):eb61741.

- dos Santos CM, Martins AB, de Marchi RJ, et al. Assessing changes in oral health-related quality of life and its factors in community-dwelling older Brazilians. Gerodontology. 2013;30(3):176–186.

- Andrade FB, Lebrão ML, Santos JLF, et al. Relationship between oral health-related quality of life, oral health, socioeconomic, and general health factors in elderly Brazilians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(9):1755–1760.

- Swoboda J, Kiyak HA, Persson RE, et al. Predictors of oral health quality of life in older adults. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26(4):137–144.

- Jung YM, Shin DS. Oral health, nutrition, and oral health-related quality of life among Korean older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34(10):28–35.

- Martins AB, dos Santos CM, Hilgert JB, et al. Resilience and self-perceived oral health: a hierarchical approach. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):725–731.

- Kim HY, Patton LL, Park YD. Assessment of predictors of global self-ratings of oral health among Korean adults aged 18-95 years. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70(3):241–244. Summer

- Silva AER, Demarco FF, Feldens CA. Oral health-related quality of life and associated factors in Southern Brazilian elderly. Gerodontology. 2015;32(1):35–45.

- Silva DD, Held RB, Torres SVS, et al. Self-perceived oral health and associated factors among the elderly in Campinas, Southeastern Brazil, 2008–2009. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45(6):1145–1153.

- Tsakos G, Sheiham A, Iliffe S, et al. The impact of educational level on oral health-related quality of life in older people in London. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117(3):286–292.

- Zhou Y, Zhang M, Jiang H, et al. Oral health related quality of life among older adults in central China. Community Dent Health. 2012;29(3):219–223.

- Hsu KJ, Lee HE, Wu YM, et al. Masticatory factors as predictors of oral health-related quality of life among elderly people in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(4):1395–1305.

- Teixeira MF, Martins AB, Celeste RK, et al. Association between resilience and quality of life related to oral health in the elderly. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2015;18(1):220–233.

- Kim H, Patton LL. Intra-category determinants of global self-rating of oral health among the elderly. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38(1):68–76.

- Pattussi MP, Peres KG, Boing AF, et al. Self-rated oral health and associated factors in Brazilian elders. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38(4):348–359.

- Andreeva VA, Egnell M, Galan P, et al. Association of the dietary index underpinning the nutri-score label with oral health: preliminary evidence from a large, population-based sample. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):1998.

- Astrom AN, Ekback G, Ordell S, et al. Social inequality in oral health-related quality-of-life, OHRQoL, at early older age: evidence from a prospective cohort study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011;69(6):334–342.

- Souza JG, Costa Oliveira BE, Martins AM. Contextual and individual determinants of oral health-related quality of life in older Brazilians. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(5):1295–1302.

- Yamamoto T, Kondo K, Aida J, et al. Association between the longest job and oral health: Japan gerontological evaluation study project cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:130.

- Lalonde M. New perspective on the health of Canadians: 28 years later. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2002;12(3):149–152.

- Inglehart MR, Bagramian R. Oral health-related quality of life. 1st ed. Ann Arbor (MI): Quintessence Pub; 2011.

- Riedel J, Wiesmann U, Hannich HJ. An integrative theoretical framework of acculturation and salutogenesis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2011;23(6):555–564. 2011/12/01

- Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1189–1108.

- Sheiham A. Oral health, general health and quality of life. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(9):641–720.

- Bassler D, Mueller KF, Briel M, et al. Bias in dissemination of clinical research findings: structured OPEN framework of what, who and why, based on literature review and expert consensus. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010024.

- Marques G. A philosophical framework for rethinking theoretical economics and philosophy of economics. London: College Publications; 2016.