Abstract

Objective

This study focuses on evaluating the long-term treatment outcome (10–15 years) and patient satisfaction after orthognathic treatment with bisagittal split osteotomy (BSSO). Furthermore, the aim was to evaluate whether the psychosocial factor, sense of coherence (SOC) associates with long-term patient satisfaction.

Materials and methods

Study sample consisted of 57 patients who had orthognathic treatment with BSSO. Self-completion questionnaires were distributed approximately 1.8 years and 10–15 years after surgery to evaluate treatment outcome. SOC was evaluated with a 12-scale questionnaire 10–15 years after the surgery.

Results

After 10–15 years following BSSO, 96% of patients were highly or moderately satisfied with the treatment outcome and none expressed dissatisfaction. Less educated patients were more satisfied with the treatment outcome than those with a higher educational level. Patients who felt clear improvement in their facial appearance expressed higher satisfaction than those experiencing only minor facial improvement. Furthermore, patients with improvement in orofacial pains and headaches more often expressed high satisfaction than those without improvement of these symptoms. Patients with strong SOC seemed to have somewhat higher scores for functional aspects of long-term treatment outcome.

Conclusions

Post-treatment satisfaction with orthognathic treatment appears to be long-lasting. Psychosocial factors may play a role in long-term post-treatment satisfaction. Our study strongly suggests that psychosocial factors should be taken into account in the treatment planning of orthognathic patients.

Introduction

Severe malocclusions and skeletal maxillofacial deformities in adults can be treated with combined surgical-orthodontic treatment. One of the most commonly used procedures for the mandible is bisagittal split osteotomy (BSSO) [Citation1]. In recent years, the surgical technique of BSSO has improved and the surgical outcome has become more predictable and reliable [Citation2]. It is acknowledged that orthognathic treatment comprises more than just correction of facial deformity [Citation3]. Several studies have demonstrated improvement in oral function, in occlusal features and in temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) after treatment [Citation1,Citation4,Citation5]. Furthermore, post-treatment patient satisfaction and psychological well-being, together with oral health and quality of life, have attracted growing interest [Citation6]. Several studies have suggested that there is a growing need for recognition of underlying psychosocial factors [Citation6,Citation7]. Benefits of orthognathic treatment may include improved self-esteem, self-confidence and personality [Citation8] as well as positive effects on oral function and psychosocial dimensions [Citation9]. Nevertheless, after the treatment some patients are dissatisfied and have difficulties in accepting the obtained results even when their treatment outcome has been professionally evaluated as successful [Citation7]. In recent years, there has been a growing interest among researchers in identifying psychosocial patterns that may affect patients’ ability to accept life changes.

‘Why do some people stay healthy whereas others do not?’ This salutogenic question was asked by sociologist Antonowsky [Citation10,Citation11]. He created the theory of sense of coherence (SOC), a theory of psychosocial factors explaining how people can manage lack of control in their lives. SOC is strongly related to perceived health and has also been shown to predict health in general [Citation10–12]. SOC appears to be capable of positively influencing the perception and promotion of health and quality of life [Citation12], although it is evident that SOC alone cannot explain patients’ overall health perception [Citation10]. People with strong SOC are, however, more likely to tolerate stress better and to make healthy choices in their lives [Citation11,Citation13,Citation14]. Strong SOC has also been associated with fewer symptoms and better self-rated health and quality of life [Citation10,Citation15].

The reported follow-up times in outcome studies after surgical-orthodontic treatment have been relatively short and only seldom extend beyond five years [Citation5,Citation16–18]. This treatment is known to be lengthy and expensive [Citation8], and it is therefore essential to also evaluate the long-term benefits with respect to patient outcome.

The objective of this study was to evaluate long-term patient satisfaction after orthognathic treatment including BSSO surgery in relation to changes in facial appearance, orofacial pain and chewing ability. Furthermore, our aim was to evaluate whether the psychosocial factor, SOC associates with long-term patient satisfaction.

Materials and methods

Study population and follow-up data

The basic study population consisted of 82 adult orthognathic patients who had BSSO surgery between 1998 and 2004 at the Clinic of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Kuopio University Hospital Eastern Finland. Of these patients 64 (78%) had mandibular advancements, and 18 (22%) had setbacks. All patients had pre- and post-operative orthodontic treatment. The mean age of the patients was 49 years at T1 (SD 10.2; range 29–67 years). At the post-treatment examination (T1, mean 1.8 years after BSSO), patients were given a questionnaire on the influence of the treatment on their masticatory function and symptoms of TMD. Subjective evaluation of treatment outcome satisfaction was also included in the questionnaire and the results have been published previously [Citation1].

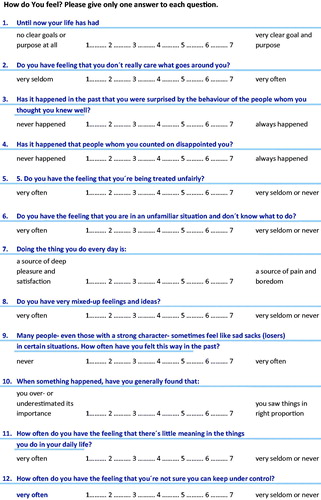

To assess long-term patient satisfaction with the orthognathic treatment outcome and to evaluate SOC (), subsequent questionnaires were sent to 77 study participants 10–15 years after the surgical procedure (T2). Five patients were (contact information not available or patient moved abroad) during the follow-up and were therefore excluded.

In total, 57 (38 females and 19 males, 74%) patients returned the long-term follow-up questionnaires. Patients were asked whether they had improved or unchanged facial appearance, self-confidence, facial pain and headaches, symptoms of TMD, and chewing ability. Patients also filled out a short version of the SOC questionnaire (12-scale, validated in Finnish [Citation12]) (), and were asked to report their marital status (single/married or cohabiting) and level of education (vocational or polytechnic/university), which were both dichotomized for the analysis.

For logistic regression analysis, a 12-item SOC scale was first divided into tertiles and then dichotomized as follows: the highest tertile was defined as strong SOC and the two lower tertiles were combined and defined as weaker SOC. An acceptable evaluation of SOC was obtained from 53 patients.

Measurement of SOC with self-evaluating questionnaires has previously been described in detail [Citation10,Citation19].

Statistical analyses

Chi-square statistics or Fisher’s exact test was used to study the differences in variables between genders and between patients with the strong and weak SOC and also among patients who reported being very satisfied and moderately satisfied with the treatment.

A multiple logistic regression model was used to evaluate the association between patients’ long-term satisfaction with treatment outcome and the following variables: marital status, education, improvement in chewing ability, improvement in facial pain and headaches, improvement in self-confidence and improvement in facial attractiveness. The effects of age and gender were also considered in the analysis.

The data were analysed using SPSS statistical software, version 21 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). For all comparisons, p values ≤.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical aspects

The Research Ethics Committee of the Kuopio University Hospital approved this study.

Results

Long-term patient satisfaction

Ten to 15 years after surgical-treatment, 68% (n = 38) of participants still expressed high satisfaction with the outcome. Twenty-nine percent (n = 17) were rather satisfied with the outcome, and self-evaluation was not available from two patients. None of the patients expressed dissatisfaction. During the follow-up (T1–T2), patients’ satisfaction with the treatment outcome appeared to remain constant, with no statistically significant variation over time. The subjective treatment outcome was as good as expected in 52% (n = 30), and better in 35% (n = 20) of the patients, respectively. Only 13% (n = 7) reported the result as poorer than they had expected.

The logistic regression model showed that patients with lower education level were more satisfied with the treatment outcome than those with higher education level (OR 0.2, CI 0.05–0.93, p = .04). Furthermore, patients who experienced improvement in their facial appearance more often expressed high satisfaction with the treatment outcome than those with less facial improvement (OR 6.4, CI 1.17–35.10, p = .03). In addition, those who experienced improvement in orofacial pains and headaches as a result of the treatment more often expressed high satisfaction with the treatment outcome than those without improvement of these symptoms (OR 5.0, CI 1.05–24.05, p = .04). The results of the logistic regression analysis are presented in .

Table 1. Associations between patients who were very satisfied with treatment outcome in long-term and gender, age, marital status, education, BSSO, change in facial pain, improved chewing ability, improved facial appearance and reduced TMD symptoms in logistic regression model.

Furthermore, in univariate analysis older patients (>40 years) and married or cohabiting patients were more satisfied with the treatment outcome than younger or single patients (p = .037 and p = .036, respectively). However, neither age nor marital status was independently associated with high treatment outcome satisfaction in the logistic regression model.

Sense of coherence

In general, approximately one-third of participants appeared to have a strong SOC 10–15 years post-operatively (T2). Strong SOC and lower SOC according to the different patient characteristics are presented in .

Table 2. Strong SOC and lower SOC according to the different patient characteristics (n = 53).

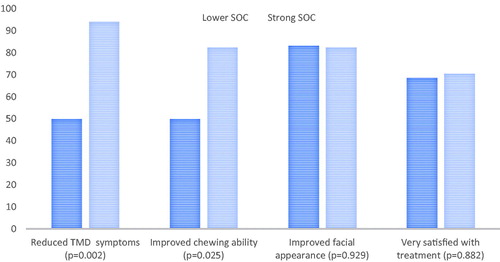

In univariate analysis, patients who reported improved chewing ability and reduced TMD-symptoms were more likely to have strong SOC (p = .025 and p = .002, respectively) (). Furthermore, patients who reported improved facial appearance and patients who were very satisfied with the treatment had no significant differences in SOC on the basis of these variables ().

Figure 2. Long-term treatment outcomes and high patient satisfaction after surgical orthodontic treatment according to SOC (n = 53).

In the multiple logistic regression analysis model with long-term treatment satisfaction, SOC was not independently associated.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the long-term (10–15 years) post-treatment satisfaction of orthognathic patients. In a single-centre prospective cohort from Eastern Finland, we report that 68% of the participants had high long-term satisfaction with the treatment outcome and 29% were moderately satisfied. None of the patients expressed dissatisfaction. Our results also indicate that a psychosocial factor, SOC, may have some role in long-lasting treatment satisfaction.

Orthognathic treatment is known generally to have a high positive impact on patients’ everyday life and well-being [Citation6–8,Citation20,Citation21]. The degree of satisfaction after treatment is a combination of patients’ motives and expectations [Citation9], and it appears that realistic expectations result in higher long-term satisfaction [Citation20].

It is widely recognized that surgical-orthodontic treatment is time-consuming, expensive and stressful for patients [Citation22]. Nevertheless, our results suggest that even 10–15 years after treatment, patients are still generally satisfied with their treatment outcome. The results presented here justify surgical-orthodontic treatment, as both short- and long-term effects of the treatment were shown to be beneficial for the patients in this cohort.

Oral health is considered an integral part of general health [Citation23]. SOC can be evaluated as an indicator of psychosocial factors that appear to also predict health in general [Citation10]. Strong SOC is commonly related to better perceived health [Citation10] and also to significantly fewer issues in oral condition [Citation10,Citation18,Citation24]. Our results also indicate that as a psychosocial factor, SOC, may have a role in long-lasting treatment satisfaction. Patients’ with strong SOC seemed to have somewhat higher scores for functional aspects of long-term treatment outcome.

Previously, more than 70% of patients were found to be satisfied with the surgical outcome, and improvement in quality of life 6 months after surgery was evident [Citation3]. The results reported here are in line with the previous data. However, it has been observed that a small proportion of patients have difficulties in adjusting to their altered appearance or changes in occlusion after treatment. Dissatisfaction has been shown to be related to unfulfilled aesthetic, functional and psychosocial expectations [Citation7]. In our study, no dissatisfaction was reported.

There are several motivational factors for seeking orthognathic treatment. Studies suggest that the main reasons are improvement in aesthetics, self-confidence and facial appearance [Citation3,Citation25,Citation26]. In addition, a combination of functional and psychological state, TMD-symptoms and preventing future problems are also common motivating factors [Citation1,Citation26,Citation27]. Patients’ hopes and expectations may not always be realistic [Citation28], and the effect of pre-treatment motives should thus be evaluated carefully with each patient individually. Interestingly in one study, patients who expected better oral function had lower post-treatment satisfaction than patients who expected better aesthetics [Citation25]. In our cohort, half of the patients reported that the treatment outcome was as good as they had expected. One-third considered it to be better than expected and approximately 10% poorer than expected. This suggests that high aesthetic expectations may be easier to fulfil with orthognathic patients than high functional expectations [Citation25]. In addition, post-treatment satisfaction may be high when aesthetic needs are met, regardless of possible residual functional problems [Citation29].

The present study indicated that patients with lower educational level are more often satisfied with the treatment outcome than patients with higher educational level, although contrary results have also been published [Citation20]. Concerning recent study [Citation30], one could speculate that the initial oral condition of the patients with lower education may have been poorer, thus leading to a greater positive treatment effect when evaluated subjectively after the treatment.

Previously, patients’ satisfaction from 8 weeks to 2 years post-surgery has been shown to correlate with age, as older patients appeared to be more satisfied post-surgically than younger patients [Citation31]. The results reported here are in line with these findings, but it has also been suggested that age and marital status do not play a role in terms of outcome satisfaction [Citation20].

In a recent review discussing the effects of BSSO on the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), the authors concluded that TMJ health could either improve or worsen as a result of this surgery [Citation32], and that there is still a lack of firm evidence concerning improvement in TMD symptoms and orthognathic surgery. In our study, patients who reported reduced TMD-symptoms were more likely to have strong SOC. Strong SOC has been associated with fewer symptoms [Citation10,Citation15] and people with strong SOC are more likely to tolerate stress better [Citation11,Citation13,Citation14]. It is well known that TMD symptoms tend to fluctuate over time and even over a long period of time, as in our study, new TMD symptoms may also occur. However, these symptoms might be due to a combination of various psychosocial factors that are not connectioned with the previously performed surgery.

The present study has some clear limitations. First, the extensive follow-up period with purely subjective reporting may cause errors, as recollection and personal experience of symptoms may alter with time. The first follow-up questionnaire was collected within the hospital, whereas the second questionnaire was sent to the patients by mail. Furthermore, SOC was only evaluated after the long-term follow-up and, therefore, any alterations in SOC level could not be detected. In addition, although the sample size was relatively small, it is comparable to other similar studies [Citation1,Citation4–6,Citation33,Citation34]. The strength of this study derives from the prospective analysis performed in a well-defined patient cohort. SOC is also a generally recognized and reliable concept in the evaluation of psychosocial factors [Citation10].

Previously, Hunt et al. [Citation8] pondered ‘Does orthognathic surgery result in psychosocial benefits for the patient?’ and concluded that nearly all previously reviewed studies suggest that orthognathic surgery has some beneficial psychosocial effects on patients [Citation8]. On the other hand, according Mihalik et al. [Citation35], patients with orthodontic camouflage were as satisfied with the treatment outcome as those who had surgery [Citation35]. This raises a question that should be considered individually before every treatment: is operative treatment the right choice when taking into account the risks and possible benefits as well as the increased costs of the treatment with surgery [Citation35]? We also draw attention to the key importance of the long-lasting effectiveness of treatments and propose that psychosocial factors should be taken into account in individual treatment planning.

In conclusion, post-treatment satisfaction with orthognathic treatment appears to be long-lasting. Orthognathic surgery may have beneficial psychosocial effects for the patients, and psychosocial factors may play a role in long-term post-treatment outcome.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Riitta Myllykangas for her contribution to the statistical analyses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Pahkala R, Kellokoski J. Surgical-orthodontic treatment and patients' functional and psychosocial well-being. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132(2):158–164.

- Ylikontiola L, Kinnunen J, Oikarinen K. Factors affecting neurosensory disturbance after mandibular bilateral split osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58(11):1234–1239.

- Proffit WR, Fields HW Jr., Sarver DM. Contemporary orthodontics. 5th ed. Oxford (UK): Mosby; 2013. p. 113–115.

- Silvola AS, Tolvanen M, Rusanen J, et al. Do changes in oral health-related quality-of-life, facial pain and temporomandibular disorders correlate after treatment of severe malocclusion? Acta Odontol Scand. 2016;74(1):44–50.

- Silvola AS, Rusanen J, Tolvanen M, et al. Occlusal characteristics and quality of life before and after treatment of severe malocclusion. Eur J Orthod. 2012;34(6):704–709.

- Alanko O, Svedström-Oristo A-L, Tuomisto M. Patients’ perceptions of orthognathic treatment, well-being, and psychological or psychiatric status: a systematic review. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68(5):249–260.

- Ballon A, Laudemann K, Sader R, et al. Patients' preoperative expectations and postoperative satisfaction of dysgnathic patients operated on with resorbable osteosyntheses. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011;2:730–734.

- Hunt O, Johnston C, Hepper P, et al. The psychosocial impact of orthognathic surgery: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120(5):490–497.

- Oland J, Jensen J, Elklit A, et al. Motives for surgical-orthodontic treatment and effect of treatment on psychosocial well-being and satisfaction: a prospective study of 118 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(1):104–113.

- Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky's sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(5):376–381.

- Antonowsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987.

- Da Costa A, Rodrigues F, Da Fonte P, et al. Influence of sense of coherence on adolescents' self-perceived dental aesthetics: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17(1):1–2.

- Antonowsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:725–733.

- Nammontri O, Robinson P, Baker S. Enhancing oral health via sense of coherence: a cluster-randomized trial. J Dent Res. 2013;92(1):26–31.

- Baker S, Mat A, Robinson P. What psychosocial factors influence adolescents' oral health? J Dent Res. 2010;89(11):1230–1235.

- Tabrizi R, Naseri N, Pouzesh O, et al. Assessment of the changes in quality of life of patients with class II and III deformities during and after orthodontic-surgical treatment. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surgery. 2016;4:476–485.

- Corso P, Oliveira F, Costa D, et al. Evaluation of the impact of orthognathic surgery on quality of life. Braz Oral Res. 2016;30(1):e4.

- Motegi E, Hatch J, Rugh J, et al. Health-related quality of life and psychosocial function 5 years after orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthoped. 2003;124(2):138–143.

- Savolainen J, Suominen-Taipale A, Hausen H, et al. Sense of coherence as a determinant of the oral health-related quality of life: a national study in Finnish adults. Eur J Oral Sci. 2005;113(2):121–127.

- Chen B, Zhang Z, Wang X. Factors influencing postoperative satisfaction of orthognathic surgery patients. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2002;17(3):217–222.

- Choi W, Lee S, McGrath C, et al. Change in quality of life after combined orthodontic-surgical treatment of dentofacial deformities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2010;109(1):46–51.

- Silvola A-S, Varimo M, Tolvanen M, et al. Dental esthetics and quality of life in adults with severe malocclusion before and after treatment. Angle Orthod. 2014;84(4):594–599.

- Cunningham S, Hunt N. Quality of life and its importance in orthodontics. J Orthod. 2001;28(2):152–158.

- Machado F, Perroni A, Nascimento G, et al. Does the sense of coherence modifies the relationship of oral clinical conditions and oral health-related quality of life? Qual Life Res. 2017;26(8):2181–2187.

- Ostler S, Kiyak H. Treatment expectations versus outcomes among orthognathic surgery patients. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1991;6(4):247–255.

- Rivera S, Hatch J, Dolce C, et al. Patients’ own reasons and patient-perceived recommendations for orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118(2):134–141.

- Pahkala R, Heino J. Effects of sagittal split ramus osteotomy on temporomandibular disorders in seventy-two patients. Acta Odontol Scand. 2004;62(4):238–244.

- Williams D, Bentley R, Cobourne M, et al. The impact of idealised facial images on satisfaction with facial appearance: comparing 'ideal' and 'average' faces. J Dent. 2008;36(9):711–717.

- Garvill J, Garvill H, Kahnberg KE, et al. Psychological factors in orthognathic surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1992;20(1):28–33.

- Sun L, Wong HM, McGrath CPJ. The factors that influence oral health-related quality of life in young adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):187.

- Scott A, Hatch J, Rugh J, et al. Psychosocial predictors of satisfaction among orthognathic surgery patients. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2000;15:7–15.

- Bermell-Baviera A, Bellot-Arcis C, Montiel-Company J, et al. Effects of mandibular advancement surgery on the temporomandibular joint and muscular and articular adaptive changes—a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45(5):545–552.

- Silva I, Cardemil C, Kashani H, et al. Quality of life in patients undergoing orthognathic surgery – a two-centered Swedish study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016;44(8):973–978.

- Schilbred Eriksen E, Moen K, Wisth PJ, et al. Patient satisfaction and oral health-related quality of life 10–15 years after orthodontic-surgical treatment of mandibular prognathism. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;47(8):1015–1021.

- Mihalik C, Proffit W, Phillips C. Long-term follow-up of class II adults treated with orthodontic camouflage: a comparison with orthognathic surgery outcomes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123(3):266–278.