Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to explore the perspectives of non-specialist dentists on the use of restraint in paediatric dentistry in the Public Dental Service in Norway.

Materials and Method

Two focus group interviews involving four and five dentists, respectively, were conducted in one of the most populated counties in Norway in September 2019. The thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke informed the qualitative analysis.

Results

According to the dentists, physical restraint in paediatric dentistry is usually used when dental treatment is absolutely necessary. The qualitative analysis revealed the following three main themes: (1) some dentists justify the use of restraint in paediatric dentistry; (2) physical restraint is often legitimised by the fact that the child is sedated; (3) the use of restraint evokes difficult ethical evaluations. Additionally, the dentists had an overarching perspective of acting in the child’s best interest, but they sometimes struggled to find a justifiable path in situations involving restraint.

Conclusions

Dentists seem to consider the use of restraint combined with sedation as legitimate for absolute necessary dental treatment. Furthermore, the use of restraint involves difficult ethical evaluations.

Introduction

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) [Citation1] underscores the importance of the participation of children in healthcare decision-making but reviews show that their participation is still sometimes suboptimal [Citation2,Citation3]. This may occasionally result in situations involving restraint. Physically forced treatment can cause anger, resistance and discomfort in children [Citation4]. Little is known about the use of restraint in paediatric health services at large and paediatric dentistry specifically. However, research from other medical health services shows that restraint can cause psychological, social and developmental burdens for children [Citation5,Citation6]. Some children are vulnerable to developing dental anxiety, and a trustful clinical relationship can be necessary for them to successfully undergo dental treatment [Citation7]. This relationship is at risk when using restraint, and children with anxiety are at higher risk of experiencing restraint than others [Citation5]. The vicious circle of dental anxiety may [Citation8], therefore, start at an early age when they experience restraint.

In this study, the term ‘restraint’ was initially understood as the administration of dental treatment despite the resistance of a child. Restraint thus involves the different means of administering a treatment against a person’s will, and it may be classified as: psychological, pharmacological and physical [Citation9,Citation10]. Psychological restraint involves verbally or non-verbally forcing a child to accept the treatment without the option of resisting. Pharmacological restraint involves the use of sedatives/medication to calm a child down, such as conscious sedation [Citation9]. Physical restraint involves physical force where the child is prevented from moving [Citation9]. In the Norwegian context, physical restraint, physical immobilisation, passive immobilisation, protective stabilisation (against one’s will) and holding are all concepts in the literature that can be considered to cover the restraint phenomenon [Citation5,Citation11,Citation12]. However, there is no consensus within dentistry on how to define or what to consider as restraint [Citation13].

Child resistance to necessary treatment is a well-known clinical challenge among dentists working in paediatric dentistry [Citation7]. To accommodate children, different behaviour management techniques (BMTs) have been used to help them receive the required dental treatment [Citation14]. The generic term, BMTs, refers to techniques for providing dental care, such as tell–show–do (TSD), positive reinforcement, distraction, conscious sedation and physical restraint. While most BMTs facilitates and enables participation in decision-making, physical restraint does not [Citation5]. Both internationally and in Norway, restraint is among the less accepted techniques [Citation14,Citation15]. Although the acceptance of restraint is decreasing, its use has not been problematised in dentistry in the same way as it has been in other paediatric health services. Being possibly harmful and violating of child autonomy, the use of restraint raises important medico-ethical questions regarding the principles of non-maleficence.

To our knowledge, no published studies have reported on the prevalence of restraint in paediatric dentistry, but restraint seems to occur frequently in dentistry [Citation13,Citation15]. Rønneberg et al. [Citation15] found that restraint in the Norwegian Public Dental Service (PDS) was most often used by dentists educated outside the Nordic region. Due to the fact that restraint is an underexplored topic in paediatric dentistry, we wanted to qualitatively gain a better understanding of the topic.

The aim of this study was to explore the perspectives of non-specialist dentists on the use of restraint when administering dental treatment on children and adolescents from 0 to 18 years of age in the Norwegian PDS.

Materials and method

An exploratory qualitative design was used [Citation16], and the data of this study were collected during two focus group interviews in September 2019.

The use of restraint involves a complex interaction between the caregiver and the patient associated with taboo and sensitive practice, which makes the topic difficult to explore quantitatively. A focus group approach was found suitable for stimulating reflection and thoughts about dentists’ understanding of their practice [Citation17]. Focus group interviews are suitable when the participants are unconscious or less aware of their views on an taken for granted practice, to capture the meaning that lies behind a topic that little is known about beforehand [Citation17]. Compared with individual interviews, the interaction between the participants allowed us to explore the participants' expressions, elaborations and exchanges of experiences, views and attitudes during interactions including valuable reactions to the other participants’ statements [Citation17]. This was especially helpful in this study because of the differing definitions of restraint among dentists.

Participants and recruitment

This study took place in the PDS in one of Norway’s most populated counties. In the PDS, all children aged from 0 to 18 years receive free dental care except orthodontic treatment, which involve individually adapted recalls at least every 2 years [Citation18]. A purposive sampling strategy based on criterion sampling was used to ensure information-rich participants [Citation19]. The following criteria were set for the dentists’ participation: a permanent position in the PDS, no management position, no specialists, and a maximum of one participant from each clinic. Of the 132 listed in the county, 98 dentists fulfilled the abovementioned criteria. Since the accessible sample included more dentists than necessary, a random sampling strategy was used to identify whom to invite (performed in Excel) [Citation19]. When 10 dentists accepted to participate, they were allocated to two groups. Each group was preconceived to consist of five participants, including both genders, dentists with ≥10 and <10 years of clinical experience and dentists working in both central and rural parts of the county. These criteria were set to avoid groups with established roles and ensure multiple interactions between the participants. The interviewer (first author) and the participants had the same county employer. However, the included participants were not close acquaintances.

In total, nine dentists participated, and they were allocated to two focus groups to allow enough time for sharing their different experiences and thoughts. The first contact was made by phone by the first author, and written information was sent by e-mail to those willing to participate in the study. Of the 15 invited dentists, 10 chose to participate. The reasons for rejection were the long journey (n = 2), inappropriate timing (n = 2) and a lack of interest in the subject (n = 1). On the day of the second interview, one person did not show up due to illness. The mean work experience was 9.9 years, with a range from 0.5 to 33 years, and they all worked with children and adolescents aged between 0 and 18 years. A brief overview of the participants is shown in . Before the interview started, the participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study. After the preliminary analysis of the two interviews, the need for further recruitment was discussed. We concluded that the research question was fully answered using the data from the two interviews.

Table 1. Gender, clinical experience and demographic distribution of the participants.

Data collection

A researcher moderated (the first author/dentist) and a research assistant assisted both interviews. Both groups were informed about the researcher’s background. The interviews took place in a quiet meeting room, and they were audiotaped with consent. They lasted for 90 min during normal work hours, and the participants’ costs were covered. The semi-structured interview guide was developed by the research team, and it has been presented in . In addition, a vignette made by the research team about a boy with toothache who experienced restraint was presented to the participants for discussion at the end of both interviews. To present, a vignette in interviews is a good way of getting honest answers about sensitive topics [Citation20]. We tested the interview guide and the vignette in a pilot focus group with public dentists in advance of the data collection, and a few adjustments were implemented.

Table 2. The interview guide used for both focus groups.

Thematic analysis

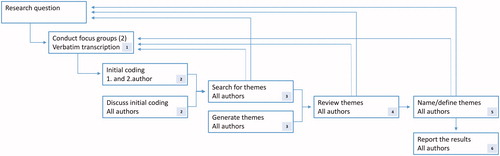

The interviews were transcribed verbatim by the first author and validated by the research assistant shortly after the interviews. This resulted in an information-rich data material that consisted of 63 computer-written pages. For example, several of the questions were not necessary because the participants answered them in their conversations. The analysis, which included the answers to all questions, was informed by Braun and Clark’s thematic analysis (TA) [Citation21]. This process has been illustrated in the schematic model in . TA is a method used to identify and analyse themes within a dataset, and it consists of six steps [Citation21]: (1) transcribing, reading and re-reading the data so that you familiarise yourself with it; (2) generating codes for the entire dataset and collating data relevant to each potential theme; (3) searching for themes and collating codes into potential themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes derived from the data; (6) producing a report [Citation21]. To organise the analysis, the first author used NVivo 12, which is qualitative data organising software. Excluding the transcription part in step 1, all authors conducted all the steps of a systematic process of discussion and reflection. The analytical process for each main theme has been exemplified in . In the results, the quotes are presented with the corresponding number of participants (ID1–9). The Norwegian quotes were translated into English by the research team and crosschecked by one native English- and Norwegian-speaking translator and one native English-speaking dental health employee.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the thematic analysis performed in this study. The arrows from steps 3–5 show that the steps are based on the research question and the data material.

Table 3. An extract from the thematic analysis showing how the main themes were established.

Results

The participants reported that the use of restraint is a part of paediatric dentistry when ‘necessary dental treatment’ must be completed. They mainly used the term restraint when describing physical restraint. In both interviews, the dentists were fundamentally concerned about acting in the child’s best interest, but they struggled in different ways to find a justifiable path. These overarching perspectives were reflected in the following three main themes: (1) some dentists justify the use of restraint in paediatric dentistry; (2) physical restraint is often legitimised by the fact that the child is sedated; (3) the use of restraint evokes difficult ethical evaluations.

Theme 1: some dentists justify the use of restraint in paediatric dentistry

All the participants recollected situations where they, or their colleagues, had used physical restraint to complete what was termed as ‘necessary dental treatment.’ It was established that it is sometimes imperative to practice restraint when administering dental treatment and that they in these situations had no alternatives. They faced an ethical dilemma of not causing harm, where restraint seemed less harmful, then not administering dental treatment when the child had dental pain. Even though the dentists mainly used the word ‘restraint’ as a synonym for physical restraint during the interviews, one dentist drew attention to how verbal restraint may occur, as shown in the following quote:

The restraint is often indirect in terms of us saying that “this must be done,” and the child doesn’t want to. ID 1

This was the only time psychological restraint was mentioned, and in the rest of this manuscript, restraint refers to physical restraint.

There was a consensus that toothache that disrupts a child’s sleep and causes difficulty with eating is the foremost reason for considering dental treatment to be necessary, even if the treatment involves the use of restraint. This is illustrated in the following quote:

She had an abscess and it was really painful! ID 6

During the interviews, personal experiences related to the consequences of not administering dental treatment were shared. The participants’ assessment of future pain and the possible need for emergency treatment were used as justifications for performing dental treatment despite the resistance of the child. The approach of habituating the child to dental treatment was considered too time-consuming when deep caries and dental pain were diagnosed, as illustrated in the following quote:

The child doesn’t sleep or eat. Takes analgesics. Toothache can be very painful. If you have a 04 [molar tooth] with a short path to the pulp and you use several hours on behavior guidance, then you have pulpitis. I have experienced it several times, and I’m sure others have as well (several agree saying ‘mmm’/nodding). Then you don’t have time. ID 8

It was emphasised that after caries is treated, there is more time to perform actions to increase the child’s ability to receive dental treatment. Furthermore, a consensus was reached that it is necessary to perform some dental trauma treatments immediately, independent of the resistance of the child.

Situations of dental treatment on the point of no return were described, where the use of restraint was demanded to complete the treatment. For example, one dentist described a treatment situation where a good relationship with the child was achieved. Everything went well during the dental treatment until the child suddenly resisted putting on the matrix system. The dentist explained how the mother had to hold the child firmly to keep the child still to enable the completion of the treatment.

In contrast to the situations described above, it was expressed that the need for treatment should always be considered carefully in advance, and ‘necessary dental treatment’ was nuanced with the following quote:

It’s rarely so urgent that you have to do something the same day. ID 4

The dentists shared doubts about judgments of the necessity of dental treatments.

Theme 2: physical restraint is often legitimised by the fact that the child is sedated

Following the assessments of the necessity of treatments, the dentists expressed how physical restraint mainly occurred when the child was sedated. It was agreed that sedation allowed dentists to perform extra-dental treatment and it lowered the threshold for restraint for completing the process. When the participants talked about restraint during dental treatment, the term ‘sedation’ was often used as a synonym for the term ‘restraint.’ A dentist expressed it like this:

When the child is sedated, my point of view is that the treatment should be done. ID 3

Another dentist described the following situation where restraint in combination with conscious sedation was the chosen alternative:

The child I’m thinking of was very special and had many big cavities. Then, I think one should give Dormicum (Midazolam) right away to treat the deep cavities, before they turn painful. ID 8

There was a general agreement that children aged from 5 to 10 years are more often subjected to sedation and restraint than those in other age groups. Children in this age group were considered by the participants to be too immature to understand their treatment needs and, consequently, less cooperative. This was also the case for younger children, but they were reported to rarely need dental treatment. The dentists agreed that a child should not experience restraint without being sedated, and used it to minimise the negative effects of the restrain, such as dental anxiety. This is illustrated in the following quote describing common preoperative information to parents before conscious sedation:

The way I view your child now, I think that if we fix this cavity when he is awake and totally alert, it could have a negative impact on future follow-ups in the dental health service. ID 6

There was disagreement on the amnestic effect of sedation.

… Then, I usually inform them that there will most likely be some crying and screaming and that it will probably be worse for them [the parents]. They will find this the toughest. Their child will remember coming and going, but won’t remember what happened in between. ID 6

Some dentists supported the statement above and concluded that the children would not return to their offices for further treatment otherwise. Other participants shared experiences of patients becoming anxious after treatment with sedation and physical restraint. One discussion concerning the amnestic effect ended with the following quote:

It’s safe to say that there is a good chance they don’t remember. To say that they won’t remember anything is a very explicit statement. ID 1

The discussion on the amnestic effect of sedation culminated with participants expressing doubt related to the use of restraint when treating children, which led to a reconsideration of its legitimacy.

Theme 3: the use of restraint evoked difficult ethical evaluations

Based on the participants’ accounts, restraint in paediatric dentistry seems to be an unclear topic entwined with challenging professional decisions and difficult feelings. The use of restraint was in conflict with their professional assessments. Notwithstanding, they occasionally used restraint, and they explained how spontaneous decision-making regarding restraint was often influenced by external factors, such as parents and the lack of time and resources. Their future decisions attached to the use of restraint were thus underpinned by difficult ethical evaluations.

The lack of time and its associated pressure evoked difficult ethical evaluations for the dentists. It was described as a dilemma when parents wanted the dentist to complete the treatment, while the dentists preferred to take their time to habituate the child to prevent dental anxiety and future avoidant behaviour. This is illustrated in the quote below:

… The parents are very thankful for it having been done. However, when they come back, my experience is that they [the children] are terrified. ID 2

The participants also had experienced a demanding workload and time-related pressure in their daily practice. They explained how the management encouraged them to focus on prophylactic treatment, helping the children to have a positive experience of dental treatment, and working more efficiently to decrease the lag in patient recalls. To save time, the use of restraint sometimes seemed unavoidable. A participant preferred to use restraint instead of sedation and TSD technique due to time-related pressure, even though restraint was undesired, as demonstrated in the following quote.

I wanted to sacrifice as little treatment and as few examination sessions as possible. ID 1

It was reasoned that if children were sedated, it would be at the expense of other patients as sedated treatment is time-consuming.

General anaesthesia was considered as an alternative to restraint, but often involved difficult ethical evaluations. Some considered general anaesthesia as the last option, only to be used when TSD and sedation were not successful, whereas one pointed out that dental treatment with general anaesthesia should be the treatment of choice for patients with substantial treatment needs. Another dentist questioned whether general anaesthesia was a viable option because the dentist was uncertain about the harm it could cause. Nevertheless, the long waiting list and rejections of references to dental treatment with general anaesthesia because of capacity limitations made them question it as a good alternative to restraint.

The dentists reported being in situations dominated by having to choose the lesser of two evils. They described situations without optimal treatment solutions when weighing their options in terms of the parents, the child, the necessity of the treatment and their access to resources. At times, this resulted in decisions they were uncomfortable about. In descriptions of restraint, negative feelings such as insecurity, sadness and helplessness were described. The use of restraint is one of the worst parts of their work, and they intimated personal desires to adjust treatments to avoid the use of restraint. Some dentists expressed adaptability in terms of overcoming negative feelings in situations of physical restraint by focussing on how they removed the child’s dental pain. Others pointed out the negative impact they suffered from these situations, both psychologically and physically, as shown in the following quote:

You don’t want to be a dentist anymore. Those days – you get a headache and feel that your legs fall asleep. You are completely exhausted. ID 9

The participants described the outcomes they observed in the children when using restraint:

I don’t find it comfortable either way, but I think to myself that at least they don’t remember it clearly afterwards. ID 3

There were things we had to do. And the father cooperated very well in performing these. He completely agreed. But the boy was furious … But now, he has become so compliant and he is not the only one. I have just remembered another one who is in the same situation. In the end, they can actually turn out to be the most compliant patients. ID 8

How the dentists perceived the reactions of the children after restraint differed. Some supported the quote above, where those children are the ones who turn out to be the most compliant patients, whereas others described anxious children. The following quote is an answer to the interviewer’s question about why these children became the most compliant patients.

He is confident with one dentist [me]. I don’t think things would go well if he was forced to change to another dentist. It is because he and I have developed a relationship.

The discussions about the use of restraint bore imprint of challenging ethical evaluations.

Discussion

This study aimed to qualitatively explore dentists’ perspectives on the use of restraint in paediatric dentistry in Norway, which is a sparsely researched topic. An important and new result in this study is that physical or psychological restraint, in combination with or without conscious sedation, in some occasions is considered unavoidable when dentists administer what they term ‘necessary dental treatment.’ What to consider as necessary dental treatment seems to be subjective. We further identified that the use of restraint was a familiar but last-resort method in use. In paediatric health services, the use of restraint is found to be comprehensive, even though it is mostly used in acute or clinically important situations, such as when the child has to be administered medications [Citation9].

The dentists treated children in the age group of 0–18 years, but restraint was reportedly used most often in the age group of 5–10 years. This finding is consistent with the use of restraint in health services at large [Citation12,Citation22]. Legally, the use of restraint in health care is regulated in most countries and patient groups [Citation1]. The UNCRC is implemented in many countries’ legislation, including Norway. Especially article 3, 12 and 24 are important for the discussion about the use of restraint in paediatric dentistry. Following Article 3, one shall always act in the best interest of the child, and Article 12 states the right of children to be listened to. Article 24 highlight the right of the child to enjoy the highest attainable standard of health [Citation1]. Further, the Patients’ Rights Act in Norway [Citation23] declares that from the age of seven, the child has the right to contribute during decision-making concerning their health, whereas from the age of 12 the child’s opinion shall be largely emphasised. Notwithstanding, parents still have the formal competence to consent until the child is 16 years old.

The dentists in this study indicated parental influence as one of the main reasons for using restraint, which in turn can mean that these dentists may be sensitive to parents’ views on restraint. Jackson et al. [Citation24] reviewed several studies on the factors that influence parents’ decision-making regarding their children’s health and concluded that parents rarely challenged the authority of health personnel, such as doctors. Venkataraghavan et al. [Citation25] summarised studies on parental acceptance of the BMTs in dentistry up until 2016 and identified a distinct trend of reduced acceptance of restraint, which is in contrast to the dentists’ experience presented in this study. Therefore, establishing a good parent-dentist relationship and communication may nuance possible misunderstandings between dentists and parents and potentially reduce the use of restraint.

The results showed that physical restraint is often combined with and legitimised by conscious sedation when the dental treatment is considered necessary and the child opposes treatment. Strøm et al. [Citation26] reported in 2015 that 18% of the asked dentists in the PDS in Norway use conscious sedation at the local clinic to provide dental care to anxious children. In this study, the dentists disagreed on the amnestic effects of sedatives and debated their contributions to the development of dental anxiety. Although the study was published in 1998, Jensen et al.’s findings have been referenced in several discussions on conscious sedation. They identified that 85% of pre-school children experienced the amnestic effect of rectal sedation when extracting a tooth [Citation27]. The children that remembered the extraction when sedated showed less acceptance of future treatment compared with the ones that did not [Citation27]. Because several children do not remember, dentists may conclude that the conscious sedation and restraint combined do not result in anxious children. Additionally, the large number of successful treatments, based on the amnestic effect, may influence and ease the justification of the use of restraint in combination with sedation by dentists.

This study indicates that the use of restraint is inflicted with difficult ethical evaluations when the dentists make individual assessments. At the beginning of 2020, The Norwegian Directorate of Health published a draft for new guidelines for dentists treating children and adolescents aged from 0 to 20 years [Citation28]. To date, the draft for the new guidelines stipulates that if restraint is necessary to complete dental treatment, the child should be sedated at the local clinic or undergo general anaesthesia. In other words, the draft for the new guidelines seems to accept restraint when the child is sedated and leaves the final decision to each dentist. The descriptions of the dentist of the combined use of restraint and conscious sedation were consistent with the upcoming guidelines. Available documentation indicates that dental treatment is better accepted by children when sedation is used [Citation27]. However, the referenced literature does not question whether the dental treatment involved the use of restraint. There is a lack of research addressing the possible psychological trauma associated with the use of restraint. If there is no clear indication of preferable evidence-based practices, it will be easier to justify the use of restraint when the child is in urgent need of dental treatment.

From what the participants in this study reported, there are negative feelings and personal stress related to the use of restraint. This is consistent with research from other health services as well, such as nurses reporting restraint in paediatric treatment as emotionally challenging [Citation29]. The self-perceived stress of dentists performing restorative treatments in children decreases with increasing age of the children from 3 to 18 years [Citation30], and high levels of stress affect the ability of dentists to make good decisions [Citation31]. To explore treatment goals and BMTs supporting the child to participate in decision-making before the consultation, can for some dentists help reduce the emotional strain.

In this study, the concern related to acting in the best interest of a child was underscored, and yet, they sometimes chose to act against the child’s will. Restraint challenges the ethical principles of nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice when it is used based on the principle of beneficence [Citation32]. The perspectives of a dentist on consequence ethics, emphasising the consequence of the act, and virtue ethics, emphasising moral excellence, seem to play major roles in the dentists’ approaches. Knowledge about possible consequences is important when weighing the pros and cons. The values of dentists may influence their choice of action. A major issue is the availability of treatment. As discussed by Rønneberg et al., the dentists interviewed also described the ethical assessment of whether patients had to wait to receive a GA appointment and endure dental pain for a long duration or get over with the procedure using restraint [Citation15]. In several cases, the last option seemed to be the choice informed by the child’s best interest. However, Bray et al. expressed concerns in 2015 regarding whether children were frequently being physically restrained for procedures that were not urgent or necessary, as a result of marginalising their voice during situations of restraint [Citation12]. Snyder concludes that the use of restraint has to be accepted on some occasions, and health personnel should be aware that they thereby compromise the child’s right to participate [Citation33]. Nevertheless, the possibility of completely safeguarding the rights of children to participate in decision-making [Citation1] is questionable when the right to receive [Citation23] and provide [Citation34] health care is legally established.

Methodological considerations

The explorative qualitative design facilitated the understanding of how restraint in paediatric dentistry can be described, discussed and used by non-specialist dentists. This study aimed to explore the use of restraint in the Norwegian PDS in general, and did not focus on specific patient groups. Overall, the dentists in the present study had relative long work experience with children in the PDS. However, they were not specialists in paediatric dentistry. In a future study, it would be interesting to explore how knowledge and training in BMT influence the use of restraint during paediatric dental treatment.

We acknowledge that the small number of participants can be a limitation. However, the informational power was considered sufficient [Citation35]. In line with Malterud et al., informational power is reached when the participants generously share their experience in such a way that the aim of the study is obtained. The informational power of this study was further strengthened through the in-depth analysis that resulted in new and nuanced patterns relevant for the study’s exploratory aim [Citation35]. Tabooed and sensitive topics can best be explored using qualitative methods obtained in a safe environment. However, further research is necessary to identify how the perspectives of this study represent the general population of dentists [Citation16].

A criterion sampling strategy was used to pre-process the sample to consist of participants with different backgrounds to ensure a wide range of viewpoints on the use of restraint [Citation19]. For example, we considered groups of participants with both short and long clinical experiences as an advantage. However, it may have affected what the participants chose to tell us, such as the case of one newly educated dentist that spoke less and may have found it difficult to speak in front of the more experienced dentists. Still, another group composition would have given rise to other issues related to the interactions. The sample of more female than male dentists was representative for the Norwegian PDS.

There are several challenges when studying one-peers [Citation36,Citation37]. Because two of the authors were dentists (the first and second authors), we may have unconsciously influenced the results [Citation37]. For example, the participants may have excluded descriptive information when articulating due to the expectation that we would understand the context of their descriptions. The pilot interview with dentists lead to a greater inclination for the interviewer to ask the participants to clarify terms taken for granted by dentists. Still, we acknowledge that our personal experiences and values influenced the interpretation of the data material [Citation36]. Therefore, we kept asking critical questions about the interpretation of the data material throughout the entire research process. The research group also consisted of a paediatric nurse (third author), who contributed by maintaining an outsider perspective during the research process.

Conclusion

This study presented selected patterns about the perspectives of non-specialist dentists on the use of restraint in paediatric dentistry. The dentists interviewed in this study reported that restraint is most often used in combination with conscious sedation, and they expressed that the use of restraint with its possible repercussions constitutes an ethical dilemma. Future research should explore the possible consequences of restraint in paediatric dentistry.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Regional Committee of Medical Ethics (REK) assessed the study and concluded that it was health service research, and it was outside its mandate (2019/570/REK Sør-Øst). However, the study adhered to the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration. The Norwegian Centre for Research Data approved the study (# 783349/2019). In advance of the data collection, the participants provided written consent after receiving written and oral information about the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants for their time and willingness to share their views and experiences on the use of restraint in paediatric dentistry.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- UNCRC. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 1989. [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx.

- Mårtenson EK, Fägerskiöld AM. A review of children's decision-making competence in health care. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(23):3131–3141.

- Coyne I. Children's participation in consultations and decision-making at health service level: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(11):1682–1689.

- Svendsen EJ, Moen A, Pedersen R, et al. Resistive expressions in preschool children during peripheral vein cannulation in hospitals: a qualitative explorative observational study. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15(1):190.

- Sturmey P. Reducing restraint and restrictive behavior management practices. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015.

- Diseth TH. Dissociation following traumatic medical treatment procedures in childhood: a longitudinal follow-up. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18(1):233–251.

- Klingberg G, Arnrup K. Dental fear and behavior management problems. Pediatric dentistry: a Clinical approach. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell; 2017.

- Berggren U, Meynert G. Dental fear and avoidance: causes, symptoms, and consequences. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109(2):247–251.

- Kangasniemi M, Papinaho O, Korhonen A. Nurses' perceptions of the use of restraint in pediatric somatic care. Nurs Ethics. 2014;21(5):608–620.

- de Bruijn W, Daams JG, van Hunnik FJG, et al. Physical and pharmacological restraints in hospital care: protocol for a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:921–921.

- Townsend JA. Protective stabilization in the dental setting. In: Nelson TM, Webb JR, editors. Dental care for children with special needs: a clinical guide. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 247–267.

- Bray L, Snodin J, Carter B. Holding and restraining children for clinical procedures within an acute care setting: an ethical consideration of the evidence. Nurs Inq. 2015;22(2):157–167.

- Kapstad J, Storesund T, Strand GV. Bruk av tvang ved tannbehandling - lov eller ikke? [The use of restraint in dentistry - legal or not?] [The use of restraint in dentistry - legal or not?]. Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. 2015;125:328–334.

- Roberts JF, Curzon MEJ, Koch G, et al. Review: behaviour management techniques in paediatric dentistry. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2010;11(4):166–174.

- Rønneberg A, Skaare AB, Hofmann B, et al. Variation in caries treatment proposals among dentists in Norway: the best interest of the child. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2017;18(5):345–353.

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488.

- Malterud K. Fokusgrupper som forskningsmetode for medisin og helsefag [Focus groups as research method in medicine and health sciences]. 2nd ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2018. Norwegian.

- Lovdata. Lov om tannhelsetjenesten [The Dental Health Services Act] Norway, 1983. Norwegian. [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1983-06-03-54.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. 4th ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2015.

- Brondani MA, MacEntee MI, Bryant SR, et al. Using written vignettes in focus groups among older adults to discuss oral health as a sensitive topic. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(8):1145–1153.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Lewis I, Burke C, Voepel-Lewis T, et al. Children who refuse anesthesia or sedation: a survey of anesthesiologists. Pediatr Anesth. 2007;17(12):1134–1142.

- Lovdata. Lov om pasient- og brukerrettigheter [Patients' Rights Act] Norway, 1999. Norwegian. [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-63.

- Jackson C, Cheater FM, Reid I. A systematic review of decision support needs of parents making child health decisions. Health Expect. 2008;11(3):232–251.

- Venkataraghavan K, Shah J, Kaur M, et al. Pro-activeness of parents in accepting behavior management techniques: a cross-sectional evaluative study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(7):ZC46–ZC49.

- Strøm K, Rønneberg A, Skaare AB, et al. Dentists' use of behavioural management techniques and their attitudes towards treating paediatric patients with dental anxiety. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2015;16(4):349–355.

- Jensen B, Schröder U. Acceptance of dental care following early extractions under rectal sedation with diazepam in preschool children. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998;56(4):229–232.

- The Norwegian Directorate for Health. Høringsutkast: Tannbarn - Kapittel 2 Barn og unge med tannbehandlingsangst (odontofobi) [Draft for consultation: Pediatric dentistry - Chapter 2 Children and adolescents with dental anxiety] [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Norwegian. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/tannhelsetjenester-til-barn-og-unge-0-20-ar-del-2-horingsutkast/barn-og-unge-med-tannbehandlingsangst-odontofobi#tannlege-eller-tannpleier-skal-benytte-det-minst-inngripende-tiltaket-nar-barn-eller-ungdommer-motsetter-seg-nodvendig-tannbehandling-begrunnelse.

- Lloyd M, Urquhart G, Heard A, et al. When a child says 'no': experiences of nurses working with children having invasive procedures. Paediatr Nurs. 2008;20(4):29–34.

- Rønneberg A, Strøm K, Skaare AB, et al. Dentists' self-perceived stress and difficulties when performing restorative treatment in children . Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2015;16(4):341–347.

- Chipchase SY, Chapman HR, Bretherton R. A study to explore if dentists' anxiety affects their clinical decision-making. Br Dent J. 2017;222(4):277–290.

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. Aufl New York: Oxford; 2013.

- Slowther A-M. The concept of autonomy and its interpretation in health care. Clin Ethics. 2007;2(4):173–175.

- Lovdata. Lov om helsepersonell [The Health Personnel Act] Norway, 1999. Norwegian. [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-64.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760.

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2009.

- Coar L, Sim J. Interviewing one's peers: methodological issues in a study of health professionals. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2006;24(4):251–256.