Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to develop a research agenda based on the most important information needs concerning the effects and outcomes of oral healthcare provided by oral healthcare professionals (OHPs).

Methods

A two-stage survey study was used to identify and prioritise topics for future research. The first survey generated topics based on information needs by OHPs. Topics were clustered thematically and overlapping topics were merged in 84 research themes. In the second survey, respondents selected their top 5 from the 84 research themes. Themes were sorted by the rank number based on rank sum.

Results

In the first survey, 937 topics were suggested. Almost half (n = 430, 46%) were identified as topics related to endodontology, cariology, oral medicine/surgery or tooth restoration. Topics were grouped in 84 research themes, covering 10 research domains. These were prioritised by 235 OHPs. Behaviour change for oral health and oral healthcare for geriatric patients ranked as most important.

Conclusions

Consultation of OHPs has resulted in a research agenda, which can be used to inform programming future oral health research. The highest prioritised research themes have an interdisciplinary nature, mainly concern oral disease prevention and are under-represented in the current oral healthcare research portfolio.

Introduction

Since the 1980s global oral health has improved, but the impact of scientific research on the delivery of oral healthcare is limited [Citation1–3]. In general, research addressing technical and scientific challenges dominates the current output of oral healthcare research [Citation4]. The limited impact of such research can be explained by different barriers for implementing evidence-based oral healthcare. For example, the accessibility to information sources, the attitude towards changes due to research findings or a mismatch between research and the information needs in daily clinical practice [Citation5,Citation6]. While the current reward system of academic excellence and funding opportunities drive research output from academic groups, research priorities are foremost defined by individual interests and expertise of principal investigators.

For different fields, healthcare mismatches have been reported between research output and research priorities as perceived by the principal consumers of the research output [Citation7,Citation8]. The interests, information needs and challenges of patients and practitioners are rarely considered in research programs. In the field of oral healthcare, oral healthcare professionals (OHPs) have sporadically been consulted on their information needs and challenges to identify priorities for a research agenda [Citation9–11]. Considering the information needs of OHPS for future research can increase the relevance of research for oral healthcare practice. Moreover, such a research agenda may help to align the challenges and information needs from OHPs with the perspectives of researchers, and is therefore considered essential to overcome the mismatch between research and practice. Involving OHPs in the programming of research will also enable to address contemporary societal challenges for oral healthcare and dental practice [Citation12]. Examples of such societal challenges are, on the one hand, the limited information on the health outcomes and (cost-) effectiveness, and on the other hand, the need for patient-centred care, transparency on quality of care, evidence-based oral healthcare and evidence-informed policy.

As such, the priorities of OHPs can inform researchers, policymakers and funders and can be used for programming future oral healthcare research [Citation12,Citation13]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop a research agenda based on the most important information needs concerning the effects and outcomes of oral healthcare encountered by OHPs in their daily oral healthcare practice.

Material and methods

In this agenda-setting project, we used a systematic and transparent methodology to identify the top-10 research themes from the perspective of OHPs [Citation14,Citation15]. For this, a two-stage online survey was used to identify and prioritise topics for oral healthcare research [Citation16]. This approach provides a process to reduce the range of responses in a group during subsequent rounds. Using such an iterative process, participants were able to use the group response of the previous round to reach a consensus. Such methodology was shown to be effective for collating different perspectives into collective judgments among stakeholders with diverse backgrounds, and has been used before to establish research priorities in many areas of health and healthcare [Citation17,Citation18].

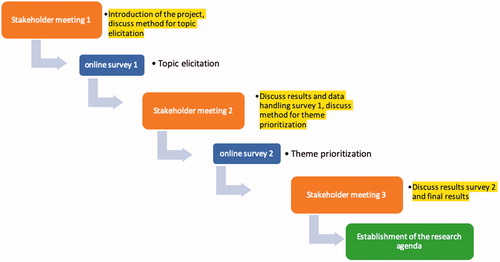

All phases of the project, notably project design, collection and analyses of data and reporting, were closely guided and monitored by a project steering group. This steering group included representatives of relevant scientific and professional organizations, societies and associations of OHPs, and convened for consultation and advice in several meetings. During these meetings, stakeholders and experts were consulted on the project design and for interpreting the findings of the project. is a schematic overview of the project, and clarifies when these meetings took place.

Ethical considerations

All participants were informed through the introductory text of the calls to participate in the surveys. This contained information on the background, aims and the design of the project. In line with General Data Protection Regulation on data safety and privacy protection, tracing back responses to individuals was not possible. A project website (www.mondzorg2020.nl) was developed containing all information about the aims, design and results of the project.

Participants and outreach

The OHPs, notably, general dentists, specialized dentists, oral surgeons, orthodontists, dental hygienists and prosthetic dental technicians, working in the Netherlands, were targeted as participants for this project. To engage these OHPs in the surveys, open calls for participation were published in printed and online media and newsletters from relevant scientific and professional organizations, societies and associations of OHPs.

Survey 1: identification of topics

The first online survey was used to generate a long list of topics. OHPs were asked to suggest at least three topics relating to their uncertainties and information needs about patient management [Citation19–22], which they consider relevant for future research. Survey 1 is displayed in supplement A. Additionally, respondents were asked to provide demographic data, notably, age, gender, year of graduation, profession, and occupational situation. Prior to distribution, five OHPs tested the text, structure and length of the survey. Based on their feedback, the text of the survey was adjusted. This online survey was available between 15th March 2016 and 31st December 2016.

Survey 1: data analysis

All suggested topics were evaluated according to the aim of this project: to identify information needs of OHPs concerning the effects and outcomes of oral healthcare. Topics beyond this scope (e.g. organisational issues) were excluded.

The first author (PvdW) analysed the data using a directed content analysis approach [Citation23–25]. All topics suggested were coded, according to a list of predefined dental research areas (based on disease, treatment or oral health specialization). This list was open for additions when required. Topics were sorted and clustered thematically, and those strongly associated or overlapping were merged. This resulted in 84 research themes. The topic coding and their thematic grouping was checked by two independent researchers. Discussion with the first author resolved all initial disagreements and consensus was reached on topic coding and their thematic grouping. Thereafter, the research themes were logically grouped, so that related themes presented specific research domains.

Survey 2: ranking research questions

The objective of the second survey was to prioritize the 84 research themes that were derived from Survey 1. Participants were asked to select their two most important themes from each of the 10 specific research domains. The full list of 84 research themes divided over the 10 specific research domains is found in supplement B. Subsequently, the list of 20 themes they selected was presented. The respondents were asked to select and rank their top 5 from these 20 themes. This stepwise approach ensured that participants would also prioritize themes beyond their personal interests and individual focus. Respondents were asked to provide demographic data, notably, age, gender, year of graduation, profession and occupational situation. The survey’s text, structure and length were tested by three OHPs, which showed that adjustments were not required. This online survey was available between 25th August 2017 and 21st December 2017.

Data analysis survey 2

Only submitted surveys with complete data were included for further analysis. The research themes were sorted by their priority as reflected from the rank number based on rank sum. The rank sum of the research themes was calculated as a product of the frequency of endorsement and weight for the ranking position. This weight was calculated as 5 − (r − 1) (r = ranking position). For example, the rank sum for a research theme ranked as #1 was calculated as 5 − (1 − 1) = 5 points, and the rank sum of a research theme ranked as #5 was calculated as 5 − (5 − 1) = 1 point.

Stakeholder meetings

Stakeholder meetings formed a structural and vital part of the project. The goal of these meetings was to engage opinion leaders from different stakeholder groups in the field of oral healthcare. Their involvement and support were crucial for the project as it facilitated outreach of the project and allowed embedding it in their network.

Prior to each survey round a meeting was organized to inform stakeholders about the different stages of the project and to discuss the design of the research agenda setting process. After the second survey a final meeting was held to discuss and validate the results from the surveys with the stakeholders.

These meetings were structured according to the World Café method [Citation26]. The World Café method is an easy-to-use approach for connecting multiple perspectives and different ideas between diverse stakeholder groups. It is designed to create a safe, welcoming environment for engaging participants in several discussion rounds. The use of this approach facilitated structured conversation and collaborative dialogue in small groups to explore the structure and process of research agenda setting.

Results

Survey 1: identification of research topics and themes

In total, 210 OHPs suggested 1103 topics for future research. Of these, 937 topics qualified for further analyses. Topics excluded for the analysis mainly concerned organisational issues in oral healthcare. The first column of displays how the 937 topics were distributed over 16 areas of oral healthcare.

Table 1. Distribution of data in each stage of the research agenda setting process.

On verification of topic coding and their thematic grouping, initial disagreement on 107 topics (10%) existed. These initial disagreements were resolved during a consensus discussion by those involved in coding and thematic grouping. Disagreements were mainly due to variability in topic allocation to the predetermined areas of oral healthcare research, based on slightly different topic interpretation. Inductive coding for additional areas was therefore required in some cases. Almost half (n = 430, 46%) of the topics were identified as disease or treatment in specific disciplines, namely endodontology, cariology, oral medicine/surgery or restoration of an element.

provides examples on how research themes were derived from topics, and how these themes were then logically grouped in a specific research domain. The grouping of topics into research themes ensured all suggested topics were represented, while it resulted in a manageable number of themes for the prioritization survey. This method firstly avoided too many very specific questions, and secondly the risk that a theme would be diluted across multiple questions.

Table 2. Illustration of data handling.

The second column of summarises the distribution of the 84 research themes over 10 specific research domains.

Survey 1: respondents

In total, 210 OHPs participated and returned a complete survey. All (sub)specialties of OHPs, were represented in this survey except oral surgeons. Most respondents were general dental practitioners (n = 99, 47%). More than half of the respondents (n = 113, 54%) were between 40 and 60 years old. presents the distribution of respondents in the first survey over the OHP disciplines and the age categories.

Survey 2: ranking research themes

presents the top-10 research themes sorted by their rank-sum. The third column of presents the specific research domain these research themes originate from.

Table 3. Distribution of respondents’ OHP disciplines and age categories.

Research themes on behaviour change for oral health, oral healthcare for geriatric patients and the relation between chronic diseases and oral health were chosen as most important research themes. In supplement A, the rank number for the 84 research themes can be found. All 84 research themes were selected as an individual top-5 at least twice (ranging from 2 to 69 times as a top-5 theme).

Survey 2: respondents

In total, 235 OHPs participated and returned a complete survey. Similar to Survey 1, all (sub)specialties of OHPs were represented except oral surgeons. Most respondents were general dental practitioners (n = 77, 33%), though their contribution was lower than in Survey 1. On average the age of OHPs participating in this survey (mean age = 45, SD = 12.8) was lower than those participating in the first survey (mean 49, SD = 12.2). presents the distribution of respondents in the second survey over the OHP disciplines and the age categories.

Stakeholder meetings

A diverse group of stakeholders including OHPs, patient representatives, researchers, medical professionals, policy makers, representatives from dental industry and research funders attended the stakeholder meetings.

During the first meeting, consensus was reached on the method to be used for topic identification during the first online survey. The importance of addressing and engaging the full range of OHPs throughout the whole project, notably, general dentists, oral surgeons, orthodontists, dental hygienists and prosthetic dental technicians was endorsed.

During the second meeting, the approach used for grouping the 937 suggested topics in 84 research themes and subsequently into 10 specific research domains was endorsed, and consensus was reached on the method to be used for theme prioritization during the second online survey.

During the third meeting, participants unanimously endorsed the ten highest prioritized research themes and thereby the final research agenda was established.

Discussion

This is the first study to establish an agenda for oral healthcare research for which a wide variety of OHP disciplines was engaged as principle stakeholders and survey participants in all phases of the project. As a result, the priorities for future oral healthcare research surpass the interests of one specific OHP discipline.

Most of the top-10 research themes prioritized by OHPs are of an interdisciplinary nature and mainly concern oral disease prevention. OHPs prioritised behaviour change and oral healthcare for geriatric patients as respectively priority research theme #1 and #2. Only two themes concern a specific dental treatment, notably priority research theme #7: ‘When has dental caries progressed so much that invasive treatment (drilling and filling) is required? What defines this treatment decision?’ and priority research theme #8: ‘What is the most effective supportive periodontal therapy (SPT) (method and frequency)?’

This oral healthcare research agenda may help to legitimately decide which research should be conducted, while reflecting the relevance for dental care practice. It may help to overcome the disconnect between the communities of researchers and practitioners and thereby prevent a mismatch of future research output. By using this research agenda as a basis for programming new research, the value of research increases, the number of (treatment) uncertainties can be reduced and the quality of oral healthcare will therefore improve [Citation12].

Since this was the first project to establish a research agenda for oral healthcare in the Netherlands, the Dutch OHPs were unfamiliar with research agenda setting. Therefore, the collection of topics took more time than anticipated, and the first survey was available online for nearly eight months. Using open-ended questions provided an opportunity for participants to identify information needs and treatment uncertainties that so far were unnoticed, and thereby reveal a-priori challenges for new areas of research. Still, some respondents indicated that they found it difficult to suggest topics and to see the long-term benefits of such a research agenda. But given the large number of topics suggested (n = 1103) this did not apply to most respondents. This large number of topics indicates that OHPs encounter treatment uncertainties and experience information needs during their work in daily practice. This adds to the strength of our approach to participant recruitment and topic elicitation. Moreover, the number of topics we have identified is comparable to that of a recent priority setting partnership (PSP) project for oral health in the UK [Citation10], but exceeds the number of topics identified in many similar other research agenda-setting projects [Citation27,Citation28].

Compared to other research agenda-setting projects for oral healthcare research, we used a different approach, as we exclusively engaged OHPs and included a broad range of OHP disciplines [Citation10,Citation11,Citation29–31]. In Canada, general dentists were only asked to prioritize oral healthcare research topics restricted to the priorities predefined and listed by researchers. The resulting topic list concerned evaluation of either effectiveness of specific treatment or the development of new materials [Citation11]. In the UK PSP project, a top-10 of research themes for oral health shared by both patients and OHPs was identified [Citation32]. Similar to our project, the PSP research priorities concern prevention and oral healthcare for special needs groups. But in the PSP, the inclusion of patient’s perspective resulted in both the accessibility and organization of the (oral) healthcare system as priorities [Citation30,Citation33].

To establish a broadly supported research agenda, we valued the representation of variety of OHPs highly important. Therefore, we reached out to all Dutch OHPs to increase ownership of the project. We sought to recruit as many OHPs as possible in both surveys and intended to involve OHPs who would otherwise not have participated. Both surveys were open for all OHPs and no specific restrictions to participation were applied, e.g. no research expertise was required. via a mix of professional media, we invited OHPs to share their information needs and contribute to the identification and prioritization of topics for future research.

As a result, we have succeeded to engage a broad selection of OHPs as respondents in both surveys. While a considerable number of OHPs have responded to and completed both surveys, due to responder anonymity it remains unclear how many have participated in both surveys.

Compared to the distribution of Dutch OHPs, in both surveys, a majority of OHPs was 50 years of age or older, but in terms of occupation, participants in both surveys form a fair representation of the Dutch OHP population. displays the distribution of respondents over the OHP disciplines and the age categories compared to the Dutch OHP population. A considerable number of respondents in both surveys were OHPs affiliated with an academic institution with a specific interest in research. Of these, several additionally worked in private practice.

The first survey resulted in a large number and a wide variety of topics addressing all fields of oral healthcare practice and research. Understandably not all OHPs hold the same views on research priorities. Therefore, the approach of research theme prioritization in the second survey was designed to ensure ranking of themes across all oral healthcare fields. This way, we challenged respondents to venture beyond their own area of specialism, invested interests or expert opinions.

Participant self-selection may introduce responder bias, i.e. the information needs from those motivated to participate may differ from those that did not participate. Although the majority of suggested topics in the first survey concerned technical aspects of treatment decisions in daily practice, in the second survey OHPs gave higher priority to societal engaged research themes. It is therefore unlikely that we have, on the one hand, disregarded substantive information needs and on the other hand, overweighed specific fields of research and practice. Moreover, the rank sum for the top-10 priorities show convergence and stability of opinions and preferences among the respondents.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed a research agenda for oral healthcare from the perspective of OHPs, which has resulted in a research agenda addressing their challenges and information needs in daily practice. Many of these themes are underrepresented in the current oral healthcare research portfolio. Researchers, policymakers and research funding agencies can use this research agenda for programming future research seeking to answer the highest prioritized questions. As in most other research agendas, the research themes we have prioritized, are broadly defined and obviously need further detailing, notably specification of research questions and elaboration of study designs. To effectively target research that meets the needs of OHPs, we advise to involve OHPs in this specification and elaboration.

Author contributions

Idea and supervision of the project: G. van der Heijden.

Design and development of study: P. van der Wouden and G. van der Heijden.

Collection and analyses of data: P. van der Wouden.

Interpretation of findings from data analyses: P. van der Wouden, H. Shemesh and G. van der Heijden.

Drafting the Manuscript: P. van der Wouden.

Critical revision of the study for important intellectual content: H. Shemesh, G. van der Heijden.

Final approval of the version to be published: P. van der Wouden, H. Shemesh and G. van der Heijden.

Table 4. Top-10 research themes for future oral healthcare research prioritised by OHPs.

SupplementB.docx

Download MS Word (17.3 KB)SupplementA.docx

Download MS Word (12.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank N.A. Verpoort and T. Haasnoot for their contribution in the analysis of the data.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

All data are available in the study.

References

- Mejàre IA, Klingberg G, Mowafi FK, et al. A systematic map of systematic reviews in pediatric dentistry-what do we really know?. PLOS One. 2015;10(2):e0117537.

- Rindal D, Rush W, Boyle R. Clinical inertia in dentistry: a review of the phenomenon. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9(1):113–121.

- Dhar V. Evidence-based dentistry: an overview. Contemp Clin Dent. 2016;7(3):293–294.

- Health Council of the Netherlands. Perspectives on oral health care. Health Council of the Netherlands; 2012.

- McGlone P, Watt R, Sheiham A. Evidence-based dentistry: an overview of the challenges in changing professional practice. Br Dent J. 2001;190:4.

- Sadeghi‐Bazargani H, Tabrizi JS, Azami , Aghdash S. Barriers to evidence-based medicine: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(6):793–802.

- Crowe S, Fenton M, Hall M, et al. Patients’, clinicians’ and the research communities’ priorities for treatment research: there is an important mismatch. Res Involv Engag. 2015;1:2.

- Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P. Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. The Lancet. 2000;355(9220):2037–2040.

- Fox C, Kay EJ, Anderson R. Involving dental practitioners in setting the dental research agenda. Br Dent J. 2014;217(6):307–310.

- Experts set top priorities for oral health research. Br Dent J. 2019;226:92–92.

- Allison P, Bedos C. What are the research priorities of Canadian dentists? J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:7.

- Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):156–165.

- Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, et al. Clinical guidelines: developing guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318(7183):593–596.

- Angulo A. Council on Health Research for Development. Priority setting for health research: toward a management process for low and middle income countries. Geneva, Switzerland: Council on Health Research for Development; 2006.

- Gibson JL, Martin DK, Singer PA. Setting priorities in health care organizations: criteria, processes, and parameters of success. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):25.

- Fitch K, editor. The Rand/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Santa Monica: Rand; 2001.

- Silva PV, Costa LOP, Maher CG, et al. The new agenda for neck pain research: a modified Delphi study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(9):666–674.

- Vohra S, Zorzela L, Kemper K, et al. Setting a research agenda for pediatric complementary and integrative medicine: a consensus approach. Complement Ther Med. 2019;42:27–32.

- Logan RL, Scott PJ. Uncertainty in clinical practice: implications for quality and costs of health care. The Lancet. 1996;347(9001):595–598.

- Liverman CT, Ingalls CE, et al. Toxicology and environmental health informative resources: the role of the National Library of Medicine. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 1997.

- Han PKJ, Klein WMP, Arora NK. Varieties of uncertainty in health care: a conceptual taxonomy. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(6):828–838.

- Osheroff JA, Forsythe DE, Buchanan BG, et al. Physicians' information needs: analysis of questions posed during clinical teaching. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(7):576–581.

- Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, et al. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs. 2018;23(1):42–55.

- Erlingsson C, Brysiewicz P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr J Emerg Med. 2017;7(3):93–99.

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288.

- Brown J, Isaacs D. The world café: shaping our futures through conversations that matter. San Francisco (CA): Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2005.

- Pollock A, St George B, Fenton M, et al. Top 10 research priorities relating to life after stroke-consensus from stroke survivors, caregivers, and health professionals. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(3):313–320.

- Knight SR, Metcalfe L, O'Donoghue K, et al. Defining priorities for future research: results of the UK kidney transplant priority setting partnership. PLOS One. 2016;11(10):e0162136.

- Visser A, van der Maarel-Wierink CD, Janssens B, et al. Research agenda oral care for older people in the Netherlands and Flanders (Belgium). Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2019;126(12):637–645.

- Everaars B, Jerković-Ćosić K, van der Putten G-J, et al. Probing problems and priorities in oral health (care) among community dwelling elderly in the Netherlands - a mixed method study. Int J Health Sci Res. 2015;5:415–429.

- Everaars B, Jerković-Ćosić K, van der Putten G-J, et al. Needs in service provision for oral health care in older people: a comparison between Greater Manchester (United Kingdom) and Utrecht (the Netherlands). Int J Health Serv. 2018;48(4):663–684.

- Oral and Dental Health | James Lind Alliance [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 28]. Available from: http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/oral-and-dental-health/.

- van Harten C, Mulder J-W. Rapport meldactie ‘Mondzorg. Utrecht: Patiëntenfederatie NPCF; 2016.