Abstract

Aim

To explore associations between salutogenic factors and selected clinical outcome variables of oral health in the elderly, combining Antonovsky’s salutogenic theory and the Lalonde Health Field concept.

Methods

The subjects comprised 146 individuals, aged 60 years and older, who had participated in a population-based epidemiological study in Sweden, 2011–2012, using questionnaire and oral examination data. A cross-sectional analysis used the selected outcome variables, such as number of remaining teeth, DMFT-index and risk assessment, and salutogenic factors from the questionnaire, clustered into domains and health fields, as artifactual-material, cognitive-emotional and valuative-attitudinal. This selection was based on findings from our previous analysis using a framework cross-tabulating two health models. The purpose was to facilitate analysis of associations not previously addressed in the literature on oral health. Bivariate and Multiple Linear Regression analyses were used.

Results

Numerous salutogenic factors were identified. Significant associations between outcome variables and salutogenic factors previously unreported could be added. Regression analysis identified three contributing independent factors for ‘low DMFT’.

Conclusions

This study supports the usefulness of a salutogenic approach for analysing oral health outcomes, identifying university education, the importance of dental health organization recall system and close social network, as important salutogenic factors. The large number of salutogenic factors found supporting oral health among the elderly indicates the complexity of salutogenesis and the need for robust analysing tools. Combining two current health models was considered useful for exploring these covariations. These findings have implications for future investigations, identifying important research questions to be explored in qualitative analyses.

Introduction

This article explored multiple factors influencing the oral health of older people from a salutogenic perspective, combining individual and structural societal levels. We used bivariate and Multiple Linear Regression, of a novel epidemiological data set for exploring salutogenic factors. We explored determinants of oral health in the elderly from a salutogenic perspective, using a framework previously developed for analysis by combining two conceptual models, Antonovsky’s theory and the Lalonde Health Field concept [Citation1]. This method using this framework allowed for concomitant disclosure of both theoretical perspectives and examination of their congruence, and salutogenic factors for oral health and Oral Health Related Quality of Life (OHRQoL) were thus identified. However, it was concluded that for individuals aged 60 years or older, there was a lack of studies with specific reference to salutogenic factors, reviewed by Shmarina et al. [Citation1]. In the present study, this method of combination of two theoretical frameworks was applied to identify salutogenic factors in a set of empirical data.

Conceptually, the group of older people may be of interest in this respect considering the lifelong impact of salutogenic factors on oral health. Of special interest is how individuals can successfully cope with detrimental factors that contribute to oral disease.

Antonovsky, in his theory, explains resilience to adversities, or why people stay healthy despite facing a wide variety of stressors, from microbiological to societal levels. The theory comprises two key elements, the Sense of Coherence (SOC) and Generalized Resistance Resources (GRRs) [Citation2,Citation3]. The SOC concept includes the ability to identify and use one’s own health resources. It reflects a person’s view of life and capacity to respond to stressful situations [Citation2,Citation3]. The GRR concept identifies resources available to enable movement towards health, or to maintain good health, and includes a range of resources, e.g. knowledge, money, social support and cultural capital [Citation2–4]. For the purposes of this paper, GRRs are referred to as ‘salutogenic factors’, i.e. factors which on the basis of epidemiological evidence, are known to promote, strengthen and maintain oral health in older people [Citation4,Citation5].

The Lalonde Health Field concept, as identified in the Lalonde Report [Citation6], was developed to provide a conceptual framework for issues related to health and disease. It identifies four principal components: human biology, lifestyle, environment, and health care organization. These four components are considered interdependent, and dynamic interactions between them over the course of a lifetime determine the level of disease, health and well-being achieved by an individual. In this present paper, the focus within the environment health field has been on societal, structural factors.

Antonovsky emphasized focussing on structures supporting health rather than on specific risk factors. He pointed out the responsibility of society to create conditions which help individuals to make healthy choices and maintain their health [Citation2,Citation7]. The Lalonde report likewise pointed out that determinants of health extend beyond traditional medical care and that health is created by complex relationships between the individual and society [Citation6]. In this sense, the health field concept offers a similar, yet wider structural perspective on the importance of salutogenic factors. Appreciating the similarities between these two concepts might help in understanding factors influencing oral health among the elderly.

Researchers have mainly focussed on relating salutogenesis to the SOC concept, thus leaving the concept of GRR unexplored [Citation1]. Even though Antonovsky pointed out: ‘it seems imperative to focus on developing a fuller understanding of those generalized resistance resources which can be applied to meet all demands’ [Citation2, p. 5], the distribution of determinants of positive health has not been studied extensively [Citation8].

Still, in salutogenic research in the field of oral health, publications are limited and concern mainly the SOC concept [Citation9,Citation10]. However, the focus of this study is on GRRs for oral health, since salutogenic factors are rather naturally clustered within different GRRs, the operators for oral health. To our knowledge, there is to date no study of the concept of oral health related to GRR in older people [Citation1]. Therefore, there is a need for further investigation into the role of salutogenic factors in oral health and how these factors contribute to positive development of oral health in the elderly. This understanding could provide a foundation for solutions to the challenges of ensuring good oral health within an expanding population of older people.

Aim

Our conceptual hypothesis was that salutogenic factors for oral health can more appropriately be studied in a group of orally healthy older people considering the lifelong impact of salutogenic factors on oral health. Thus, the aim was to explore, in the elderly, the associations between salutogenic factors and outcome variables of oral health, using three variables reflecting the profession’s traditional view on oral health (number of remaining teeth, DMFT-index, risk assessment), and two variables reflecting the patient’s view on oral health, using global variables related to OHRQoL. The variables were selected by combining two theories of salutogenesis [Citation1], revealing several associations indicating factors for salutogenesis among elderly. Those factors were tested for validity in an empirical sample. We also focussed on identifying previously undescribed associations.

Material and methods

Study design

The population-based epidemiological study in the Region Kalmar county

This cross-sectional study was based on data derived from a population-based epidemiological study carried out in the Region Kalmar County, Sweden, 2011–2012. This region is a county in the south-eastern part of Sweden. It is a rural county where around 40 per cent of the population live in the countryside. The business structure of the county is mainly represented by industries such as agriculture, forestry and manufacturing. The county is divided in twelve municipalities with a total population around 245,000. One third of population in Sweden is aged 60 years or older (Statistics Sweden). The study was designed to collect information about characteristics relevant to the adult population’s oral health, and duplicated methods previously used for data sampling in the Region of Skåne. For detailed information about the clinical examination, see Lundegren et al. [Citation11].

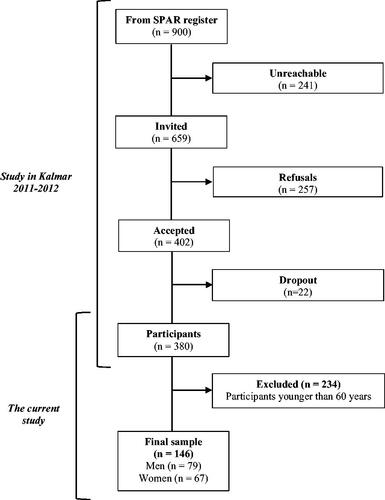

Briefly, a random sample of 900 individuals was obtained from SPAR (The Swedish State Personal Address Register). SPAR holds information on every person registered as a citizen in Sweden. Individuals aged between 20 and 90 years old were invited to participate in a free oral examination, 659 was reachable for contact and 402 accepted. The final sample consisted of 380 participants (58%) who completed the questionnaire and participated in the oral health examination, and 146 were 60 years or older and comprised the evaluated sample ().

The information was collected via a pre-existing questionnaire consisting of 56 questions on general and oral health, need for dental care, experience of appointments for dental care, and on socio-economic factors [Citation11]. The clinical examinations were undertaken by two dentists and were carried out in four different public dental clinics. The dentists were co-ordinated with respect to diagnostic criteria by means of comprehensive written instructions, practical exercises and discussion of clinical cases. All patients were examined using standard examination procedures in standard surgeries. The clinical examinations included one panoramic and four bitewing radiographs and five intra-oral clinical photographs [Citation11].

Clinical outcome variables included the number of remaining teeth and risk assessment. The DMFT-index (28 teeth) for each individual was calculated using the clinical status form [Citation12]. All missing teeth and restorations were considered to be due to caries.

The risk assessment was developed and used by all dental practitioners in the public dental care in the Region Kalmar County for several years at annual check-up appointment. The risk assessment was based on current scientific knowledge and developed by relevant dental care developers. It assessed the patient’s risk for developing dental diseases and was used for applying an individual treatment plan. All dental practitioners were introduced and trained in using the risk assessment. Briefly, the risk assessment consisted of general risk, caries risk, periodontal risk and technical risk. Each of those were divided into three categories depending on the risk for developing disease (0–3). The score for each risk category added up to the risk sum.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Board at Lund University, Dnr 2011/366. The participants received written and verbal information about the aim of the study and were informed that they had the right to withdraw without having to specify the reason and that confidentiality was guaranteed. All participants signed the informed consent form.

Participants

The study sample was selected from participants in the population-based epidemiological study in the Region Kalmar County. We analysed the data from participants aged 60 years and older. In total, 146 participants (male: 54.1 per cent) were included () (mean age: 70.1 years; SD: ± 7.3 years) as described in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for age and dentition status assessed by three oral health indicators (n = 146).

Variables

The selection of variables for analysis in the present study was based on a framework combining two conceptual models, Antonovsky’s theory and the Lalonde Health Field concept, and intended to represent all components of this framework. Detailed information on the framework can be found in Shmarina et al. [Citation1]. The variables selected from the questionnaire were determined with the aid of the framework so that salutogenic factors for oral health could be identified in the empirical dataset. They encompass socio-economic factors, self-perceived oral health and treatment needs, as well as reported oral health self-care, and clustered under the appropriate GRR domains and health fields, such as artifactual-material, cognitive-emotional and valuative-attitudinal ().

Table 2. Distribution of salutogenic factors, n (%).

Outcome variables

The status of the dentition was based on three clinical outcome variables as indicators of oral health: number of remaining teeth, the DMFT-index and risk sum (). For the purpose of bivariate analyses, the population was separated into quartiles for each of three variables. Participants with the best oral health are those with the quartiles with the highest number of remaining teeth (quartile P75), the lowest DMFT-index (quartile P25) and the lowest risk sum (quartile P25). Participants with the poorest oral health are expressed as those with quartiles with the lowest number of remaining teeth (quartile P25), the highest DMFT-index (quartile P75) and the highest risk sum (quartile P75).

Two global outcome variables were also identified in responses to the question ‘Are you confident of maintaining good oral health for the rest of your life?’ with response categories ‘yes’ and ‘no’, as well as the question ‘How do you assess your future dental care need?’ with response categories ‘little or none’ and ‘large’ (). The rationale for introducing these global variables was to reflect the salutogenic perspective for OHRQoL. However, those variables could also reflect important patient salutogenic characteristics. Previous studies have shown that self-perceived oral health can be used as relevant indicator of clinical findings [Citation13–16].

Table 3. Outcome variables and their coding. The coding has a consistently salutogenic direction.

Salutogenic factors

In total 25 factors from the questionnaire were identified as salutogenic (), using a cross-tabulation described in . See factors identified for this study, indicated by bold text. Other factors were previously identified in the literature [Citation1].

Table 4. Cross-tabulation of reported salutogenic factors significantly associated with better oral health among people ≥60 years, sorted according to Antonovsky’s salutogenic theory General Resistance Resources (GRRs), and the Lalonde Health Field concept.

Principle for analyses

Salutogenic factors selected for the analyses were sorted according to a previously developed framework combining Antonovsky’s GRR domains and Lalonde’s health fields [Citation1]. For example, a salutogenic factor ‘refrain treatment need due to cost’ was organized under the Lifestyle health field and further under the Artifactual-material GRR domain. The coding had a consistently salutogenic direction.

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (v.21, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA). Frequencies were used for descriptive statistics. To test associations between oral health measures and variables of interest, we used Fisher’s exact test. A p-value ≤.05 was considered as significant. A φ coefficient was calculated for every variable to assess the degree of correlation. Significance levels of correlations of 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 were considered as indicating weak, moderate and strong, respectively.

A Multiple Linear Regression was used to analyze how DMFT-index was dependent on background variables.

Results

Sample characteristics

presents the sample characteristics of population for the three oral health indicators: number of remaining teeth, DMFT-index and risk sum.

Bivariate analysis

presents the result of bivariate analyses for each salutogenic factor and outcome variable.

The answers to the global questions ‘Are you confident of maintaining good oral health for the rest of your life?’ and ‘How do you assess your future dental care need?’ correlated well with one another as well as with the oral health indicators.

The overall impression was that a number of significant correlations were to be found, especially within the Lifestyle Health Field and Psychosocial GRR domains. Only singular correlations were found within the other three health fields.

General consistency

There was a consistency of associations between a given salutogenic factor and the outcome variables. Thus, a given salutogenic factor correlated mostly in the same direction (negative or positive correlation) with the outcome variables.

Human biology health field

Within this field only one significant weak interaction was found (). Being male was weakly correlated with a low risk sum.

Lifestyle health field

A large number of significant correlations were found between salutogenic factors and outcome variables within this health field (). However, only three salutogenic factors demonstrated associations with all oral health indicators, at various degrees of significance. These variables were ‘refrain treatment need due to cost’, ‘self-perceived treatment need at present for prosthetics’ and ‘smoking’. Strong positive correlations were disclosed between not ‘refraining treatment need due to cost’ and ‘high number of remaining teeth’, no ‘self-perceived treatment need at present for prosthetics’ and ‘high number of remaining teeth’ as well as ‘smoking’ and ‘low risk sum’.

Except for ‘smoking’, within the ‘preventive health orientation’ domain, only two significant weak associations with oral health indicators and few with global indicators emerged. No ‘self-initiated latest dental care visit’ was weakly correlated with ‘high number of remaining teeth’ as well as both global indicators. ‘Tooth brushing’ at least twice a day was weakly correlated with ‘low risk sum’ and being ‘confident in maintaining good oral health’. ‘Dental care visits’ once a year or less and ‘additional fluoride’ used never or sometimes were weakly correlated with ‘own assessment of future dental care need’ as little or none.

With respect to the Valuative-attitudinal GRR domain, ‘dental personnel’ as a factor for greater ‘responsibility for one’s oral health’ did not correlate with any of the clinical outcome variables. However, taking a large ‘own responsibility’ was moderately correlated to low risk sum and little responsibility of ‘family or social network’ showed a moderate correlation with low DMFT-index.

Two salutogenic factors were also assessed as global outcome variables, on the basis of their global character, namely ‘confident in maintaining good oral health’ and ‘self-assessment of future dental care need’. Their global character was here demonstrated by strong positive associations with all outcome variables. Being ‘confident in maintaining good oral health’ as well as ‘self-assessment of future dental care need’ as little or none were correlated with a ‘high number of remaining teeth’, ‘low DMFT-index’ and ‘low risk sum’.

Environment health field

Two positive significant associations were observed within this health field. ‘Can afford suggested treatment’ was moderately correlated with ‘confident in maintaining good oral health’. ‘Living alone’ was weakly correlated with little or no ‘self-assessment of future dental care need’.

Health care organization health field

Within this health field, three positive significant interactions were found for one salutogenic factor. ‘Clinic’s recall system’ was weakly correlated with ‘high number of remaining teeth’ with being ‘confident in maintaining good oral health’ and to little or no ‘self-assessment of future dental care need’.

Multiple linear regression analysis

A Multiple Linear Regression model using DMFT-index (10–28) as the dependent variable, had a good model fit of R Square 0.499 (). Three independent variables showed a significant (p < .05) relation (B) to the DMFT-index: a university level education (p = .041, B −2.629); a high self-assessed importance of dental personals’ responsibility for one’s own oral health (p = .040, B −3.755); a high self-assessed importance of the responsibility of the family or social network for one’s own oral health (p = .006, B −4.381). In comparison to findings in , education level and high self-assessed importance of dental personals’ responsibility for one’s own oral health were non-significant. A high self-assessed importance of the responsibility of the family or social network for one’s own oral health was significant (p = .01).

Table 5. Summary for linear regression analysis for salutogenic factors predicting DMFT-index (10–28, n = 74).

Cross-tabulation

In this study, we did not identify any salutogenic factor for oral health in this population which could be added to previously described empty cells in the cross-tabulation () [Citation1]. However, several salutogenic factors could be added to three health fields: Lifestyle, Environment and Oral Health Organization, that already contained some salutogenic factors as identified previously [Citation1]. The majority of the salutogenic factors identified were added to the Lifestyle health field and concerned ‘self-perceived treatment need’, ‘responsibility for one’s oral health’ and ‘self-assessment of future dental care need’.

Discussion

The aim was to explore relevant salutogenic factors for oral health in people aged 60 years and older. We could corroborate the strength of our tool for exploring salutogenic interactions as used in our previous study reviewing salutogenic factors for oral health [Citation1]. Furthermore, we could add some previously unreported associations and also confirm results reported by other authors. Thus, our conceptual hypothesis was corroborated, i.e. salutogenic factors for oral health can more appropriately be studied in a group of orally healthy older people considering the lifelong impact of salutogenic factors on oral health.

We used epidemiological data, with special reference to unexplored associations identified in previous research [Citation1]. Even though we could not identify salutogenic factors for oral health in this population which could be added to previously described empty cells in the cross-tabulation (), we could add several factors.

Previous research in the oral health field has focussed primarily on lifestyle factors, leaving other areas unexplored. Although lifestyle is important for maintaining good oral health, there might be a number of unknown salutogenic factors in other health fields. Therefore, for this study, we selected data from a questionnaire, in order to extend the search for possible information beyond the lifestyle area. Our results indicate that there is a lack of information outside the lifestyle area with a need to expand the perspective by empirical studies focussing on unexplored areas. However, in the complex relations between salutogenic factors and outcome variables, one must recognize that there are many confounding indirect effects depending on hidden factors.

Sample

Internationally, the age-related number of natural teeth varies substantially. A study of 14 European countries and Israel disclosed that in people aged 50–90 years, Sweden has the highest median (27.0) and mean (24.5) number of natural teeth [Citation17]. The same study also showed that Sweden is one of the few countries where at least half of the population aged 80 years or older has at least 20 teeth remaining [Citation17]. In our study, the population median and mean number of remaining teeth did not differ considerably from the study cited above. This similarity in the number of remaining teeth could be attributable to variations in age range and study methods (self-reported number of teeth). Thus, the figure for remaining teeth in our sample may be considered representative for this age group.

Bivariate analysis

Earlier research indicates that socioeconomic background, health-related behaviour patterns in early life, and previous disease experience are important determinants of oral health outcomes up to middle age [Citation18]. However, to date there is little research into the influence of Health Care Organization, even though it is up to the individual to explore and benefit from the available health support. Compared with many other countries, oral health care organization in Sweden is highly developed. It might be assumed that the high level of tooth retention in Sweden is associated with a long history of this general oral health care organization and the individual’s ability to access it. This includes systematic preventive efforts and subsidies for treatment, which might be reflected in the current oral health status among elderly Swedes.

In this study, a number of significant correlations within the Lifestyle health field were identified. Within the other fields, there were only a limited number of variables and some single significant correlations. A reason might be that the original data used for this study comprised primarily lifestyle variables, leaving insufficient data for other health fields.

The findings demonstrate associations indicating that it is of value to oral health if an individual takes his/her own initiative and responsibility. Those who reported taking major responsibility had a significantly lower risk sum and those who placed little responsibility on family or social network had significantly lower DMFT-indices. These findings are consistent with theories [Citation2] and previous empirical research, as expressed by factors such as ‘higher conscientiousness’ [Citation19] and ‘likely cooperate’ [Citation20]. Dahlgren and Whitehead [Citation21] in their comprehensive model of the impact of social and community network factors very clearly points out these factors as contributing salutogenic factors [Citation21].

In the present population, only a few weak connections could be disclosed between oral health-related outcome variables and salutogenic factors within preventive health. The only exception was ‘never smoking’, which was consistently associated with all clinical and global oral health indicators. This is in accordance with earlier research [Citation22–24].

Further, more frequent use of additional fluoride and more frequent dental care visits were associated with self-assessment of future dental care need. Interpreting ‘frequent dental visits’ as healthy behaviour might need some modification, taking into account the reasons for the frequent visits. They might just as well be due to recurring problems as to preventive treatment recommended by the clinic. However, our other finding demonstrated an association between frequent recall by the clinic and better oral health outcomes. Those who were recalled by the dental clinic had more teeth and also assessed their future dental care need as little or none. This finding could support Antonovsky’s theory, placing the power ‘where it is legitimately supposed to be’ [Citation2, p.128], i.e. in the hands of dental professionals and the dental organization system. The importance of an effective dental recall system has also been reported previously [Citation25].

Moreover, some findings were consistent with previous research, e.g. financial security was associated with better oral health [Citation26,Citation27]. Lack of self-perceived need for prosthetic treatment correlated positively with all outcome variables. This result is as expected, even with the high number of teeth in this population. Tertiary education was positively correlated with a higher number of natural teeth, which is in accordance with earlier research [Citation19,Citation28,Citation29].

The variables ‘confident in maintaining good oral health’ and ‘self-assessment of future dental care need’ as little or none, were significantly correlated with each other and with all other outcome variables. Thus, they can tentatively be regarded as global indicators of oral health. To our knowledge, these variables have not been considered as such previously [Citation30,Citation31].

Several research methodologies may be applied to assess the nature of salutogenesis, what individually determines behaviour and the competence of the individual to actually find and use societal structures supporting health [Citation2]. Certainly, a qualitative and more direct approach such as asking (interviewing) resilient individuals how they deal with their challenges, would help in understanding salutogenesis.

Multiple linear regression analysis

This model had a high model fit, i.e. it was well specified regarding its independent factors, which were selected from a theoretical standpoint emanating from those of Antonovsky and Lalonde. Three independent factors were significantly associated with the dependent variable. A lower DMFT index was more associated with a higher education (university education), thus confirming previous studies relating a higher degree of education with better oral health [Citation28]. A lower DMFT index was also related to both a self-assessed lower importance of dental personals’ responsibility for one’s own oral health, as well as a lower self-assessed importance of the responsibility of the family or social network for one’s own oral health. This implies that an individual in a well-functioning social network, either of professional or private character, will profit from this when the individual takes own responsibility in regard to oral health. A causal relationship must ultimately be based on theoretical reasoning. The mechanism for this case-effect relationship would presumably be through social networks offering social structures empowering the individual towards healthy practices as stressed by both Antonovsky and Lalonde [Citation2,Citation3,Citation6].

Limitations

One limitation was population size due to the data used in the present study. The generalizability of the present findings is also limited and cannot be regarded as representative of the entire Swedish population, even though with respect to the number of remaining teeth, the sample did not differ from that of Stock et al. [Citation17]. Moreover, the data in the present study was originally collected by using the same selection procedures and methods as in a similar previous study in Skåne [Citation11]. Our findings demonstrate similar trends.

Although the lack of calibration among clinical examiners presents a limitation, the experienced dentists were using their regular clinical procedures and were co-ordinated with respect to diagnostic criteria by means of comprehensive written instructions, practical exercises and discussion of clinical cases. For the purpose of this study these procedures were considered appropriate.

Another limitation is that the original questionnaire was constructed from a pathogenic perspective, which limited the choice of variables for the present study. Empirical studies designed from a salutogenic perspective are needed. Finally, because of the cross-sectional design, the present study cannot claim causal relationships. There is a possibility of bidirectional relationships between oral health indicators and the selected variables.

Conclusion

This study supports the usefulness of a salutogenic approach for analysing oral health outcomes, identifying university education, the importance of dental health organization recall system and close social network, as important salutogenic factors. The large number of salutogenic factors found supporting oral health among the elderly indicates the complexity of salutogenesis and the need for robust analysing tools. Combining two current health models was considered useful for exploring covariations between salutogenic factors and several outcome variables within oral health. These findings have implications for future investigations, identifying important research questions to be explored in qualitative analyses.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge with gratitude statistical advice from Per-Erik Isberg, B.Sc., Department of Statistics, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Shmarina E, Ericson D, Åkerman S, et al. Salutogenic factors for oral health among older people: an integrative review connecting the theoretical frameworks of Antonovsky and Lalonde. Acta Odontol Scand. 2021;79(3):218–231.

- Antonovsky A. Health, stress and coping. 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982.

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health. How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987.

- Lindström B, Eriksson M. The hitchhiker's guide to salutogenesis: Salutogenic pathways to health promotion. Helsinki: Folkhälsan; 2010.

- Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):725–733.

- Lalonde M. A new perspective on the health of Canadians. A. working document. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 1974.

- Antonovsky A. Some salutogenic words of wisdom to the conferees. Sweden: The Nordic School of Public Health in Gothenburg; 1993 [cited 2020 Dec 21]. Available from: http://www.angelfire.com/ok/soc/agoteborg.html

- Peel NM, McClure RJ, Bartlett HP. Behavioral determinants of healthy aging. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(3):298–304. Apr

- Possebon A, Martins APP, Danigno JF, et al. Sense of coherence and oral health in older adults in Southern Brazil. Gerodontology. 2017;34(3):377–381. Sep

- Bernabe E, Watt RG, Sheiham A, et al. Sense of coherence and oral health in dentate adults: findings from the Finnish Health 2000 survey. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37(11):981–987. Nov

- Lundegren N, Axtelius B, Akerman S. Oral health in the adult population of Skåne, Sweden: a clinical study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2012;70(6):511–519. Dec

- Petersen PE, Baez RJ. World Health O. Oral health surveys: basic methods. 5th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- Blizniuk A, Ueno M, Zaitsu T, et al. Association between self-reported and clinical oral health status in belarusian adults. J Investig Clin Dent. 2017;8(2):206.

- Tseveenjav B, Suominen AL, Varsio S, et al. Do self-assessed oral health and treatment need associate with clinical findings? Results from the finnish nationwide health 2000 survey. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72(8):926–935.

- Lundegren N, Axtelius B, Akerman S. Self perceived oral health, oral treatment need and the use of oral health care of the adult population in skåne. Swed Dent J. 2011;35(2):89–98.

- Inglehart MR, Bagramian R. Oral health-related quality of life. 1 ed. Ann Arbor: Quintessence Pub; 2011.

- Stock C, Jurges H, Shen J, et al. A comparison of tooth retention and replacement across 15 countries in the over-50s. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44(3):223–231. Jun

- Listl S, Broadbent JM, Thomson WM, et al. Childhood socioeconomic conditions and teeth in older adulthood: Evidence from SHARE wave 5. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46(1):78–87. Feb

- Môttus R, Starr JM, Deary IJ. Predicting tooth loss in older age: interplay between personality and socioeconomic status. Health Psychol. 2013;32(2):223–226.

- Bomfim RA, Frias AC, Pannuti CM, et al. Socio-economic factors associated with periodontal conditions among brazilian elderly people – Multilevel analysis of the SBSP-15 study. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206730.

- Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Background document to WHO – Strategy paper for Europé. 1991. Available from: https://www.iffs.se/media/1326/20080109110739filmz8uvqv2wqfshmrf6cut.pdf

- Carson SJ, Burns J. Impact of smoking on tooth loss in adults. Evid Based Dent. 2016;17(3):73–74.

- Pham TA, Ueno M, Shinada K, et al. Periodontal disease and related factors among vietnamese dental patients. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2011;9(2):185–194.

- Arora M, Schwarz E, Sivaneswaran S, et al. Cigarette smoking and tooth loss in a cohort of older australians: the 45 and up study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(10):1242–1249. Oct

- Astrom AN, Ekback G, Ordell S, et al. Long-term routine dental attendance: influence on tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life in swedish older adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2014;42(5):460–469.

- Swoboda J, Kiyak HA, Persson RE, et al. Predictors of oral health quality of life in older adults. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26(4):137–144.

- Martins AB, dos Santos CM, Hilgert JB, et al. Resilience and self-perceived oral health: a hierarchical approach . J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):725–731. 2014-11-26

- Paulander J, Axelsson P, Lindhe J. Association between level of education and oral health status in 35-, 50-, 65- and 75-year-olds. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30(8):697–704. Aug

- Aida J, Kuriyama S, Ohmori-Matsuda K, et al. The association between neighborhood social capital and self-reported dentate status in elderly Japanese-the Ohsaki Cohort 2006 Study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39(3):239–249.

- Bourgeois DM, Llodra JC, Nordblad A, et al. Report of the EGOHID I Project. Selecting a coherent set of indicators for monitoring and evaluating oral health in Europe: criteria, methods and results from the EGOHID I project. Community Dent Health. 2008;25(1):4–10. Mar

- Revision to the National Oral Health Surveillance System (NOHSS) Indicators www.cdc.gov: Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; [updated 2015 April 1; cited 2020 Dec 21]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealthdata/overview/nohss.html.