Abstract

Objective

Mapping key themes that characterize challenging and positive encounters in dental practice using online reviews of patient satisfaction.

Materials and methods

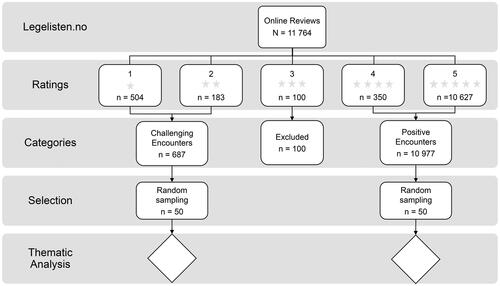

11,764 online patient reviews of dental encounters, consisting of an overall satisfaction rating (1–5 stars) and a free-text response, were collected from the web-site Legelisten.no. The reviews were split into two sets: reviews from patients with low satisfaction (1–2 stars) representing challenging encounters vs. patients with high satisfaction (4–5 stars) representing positive encounters. A qualitative thematic analysis was used to analyse the text materials in the datasets.

Results

Five key themes to both challenging and positive patient encounters were identified: (1) Interpersonal factors, (2) Patient factors, (3) Dentist factors, (4) Situational factors, and (5) Consequences. These themes are discussed in light of their role in challenging and positive patient encounters, as well as previous studies of online reviews and patient satisfaction.

Conclusions

Based on the patients’ experiences with dental encounters, challenging encounters seem to arise when dentists’ personality traits and communication skills fail to match the patients’ expectations or preferences. It appears central to patient satisfaction that dentists are able to shift between different communication styles in order to adapt to the personality and preferences of the patients.

Introduction

Recent research suggest that online reviews might be a useful source of information regarding patient preferences and satisfaction with health care services [Citation1,Citation2], which also includes patients’ perspectives on negative experiences and dissatisfaction [Citation3]. While online reviews often contain numeric indications of satisfaction or dissatisfaction [Citation4], they frequently also include commentary sections that enable patients to express their opinions in free text. This might provide new insights into the patients’ perspectives with regards to health care quality [Citation1,Citation2]. Research on internet behaviour have found evidence of increased self-disclosure when communicating online, compared to self-disclosure face to face [Citation5,Citation6]. This is suggested to be due to psychological mechanisms such as percieved anonymity on the internet or perceived social support in internet based groups (forums, facebook-groups etc.) [Citation5,Citation6]. Online content from web-sites containing free text, such as patient authored reviews, could thus provide ‘unfiltered’ information on patients’ preferences in health care settings, that is perhaps different from the traditional research using surveys or interviews. Investigating online reviews should be of high importance to health professionals, as they are increasingly used by patients when selecting health professionals [Citation2,Citation7,Citation8].

For many health professionals, challenging patient encounters, or challenging situations with patients, are not uncommon occurrences [Citation9,Citation10]. These encounters might occur whenever there are fundamental differences between the health professionals’ and the patients’ view of the situation [Citation11–15]. Unfortunately, health professionals might lean towards referring to these encounters as dealing with ‘challenging patients’ or ‘difficult patients’ [Citation14,Citation16]. These terms arguably place responsibility on the patient as the single contributor to the challenging situation, and therefore it might be more appropriate to refer to these encounters as ‘challenging relationships’ [Citation17,Citation18]. Challenging encounters have been found to occur more often when patients experience underlying psychosocial struggles like anxiety and depression [Citation18,Citation19]. In addition, lack of experience in health professionals might exaserbate the challenging encounter. For instance, health professionals who were less experienced and failed to discover the underlying psychosocial issues of their patients, were more likely to experience challenging encounters with patients [Citation18,Citation19]. Moreover, health professionals who feel incompetent in treating the disease or alleviating the patients’ symptoms, or who display symptoms of burnout, are more suspectible to experience the encounter as challenging [Citation18].

In recent studies dentists have reported that 25% of their patient meetings were experienced as ‘challenging’ [Citation18,Citation20]. Such encounters might contribute to increased perceived negative work stress and burnouts in dentistry [Citation18,Citation21–23]. The patients’ perspective of the challenging encounters in dentistry is sometimes investigated through measurements of patient satisfaction [Citation24,Citation25], and patient satisfaction is also often used as a measurement of ‘health care quality’ [Citation26,Citation27]. Research from different healthcare contexts have found that increased patient satisfaction is linked to better treatment outcomes [Citation28,Citation29] and better motivation and compliance [Citation30–32]. Oral diseases like periodontitis and caries, are often managed through oral hygiene behaviour change and lifestyle changes [Citation33], requiring patient compliance and cooperation between patients and dental health professionals. Increasing patient satisfaction could thus benefit both the dentist and the patient, improving treatment outcomes and reducing burnouts of dentists [Citation21,Citation28].

Patient satisfaction in dental health settings seems to be closely related to the communication between the dental health practitioner and the patient [Citation34–36]. Research also suggest that there seems to be a connection between the patient’s satisfaction and whether their expectations are fulfilled [Citation25,Citation34,Citation37,Citation38]. While there exists a large body of research on the different contributing factors to patient satisfaction [Citation26,Citation27], much of the research relies on patient interviews and surveys. Also, the approaches taken to measure patient satisfaction are almost exclusively defined by health care providers and therefore might fail to measure the issues most important to patients [Citation1,Citation39]. For some time, researchers have advocated that one should include patients’ perspectives in research in order to achieve more patient relevant findings [Citation40,Citation41]. Online reviews could provide researchers with useful research findings, consistent with a patient-centred approach.

In this study, the aim is to map key themes that characterise challenging and positive encounters in dental practice using online reviews of patient satisfaction with Norwegian dentists. Exploring the patients’ views of challenging encounters through online reviews, can give new insight into this topic.

Methods and data collection

This study adopts a qualitative approach investigating challenging encounters from the patients’ perspective. A thematic analysis was conducted on text material from a commentary section of online patient reviews of dental treatment. The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, reference number 468642.

Patient reviews of dental visits published on the website Legelisten.no [Citation42] from between June 2013 and July 2020 were included in this study. In total, 11,764 reviews were acquired by the authors through an agreement with the website provider. Legelisten.no is a privately founded website where patients can evaluate different categories of health professionals, for instance medical doctors, dentists and chiropractors, with the aim to help people that are in need of health services choose among health care providers. Both general dental practitioners and specialists can be evaluated.

All reviews were registered voluntarily online by users which have met with the dentists that were reviewed. In the data set provided by Legelisten.no both the dental practitioners that are reviewed and the patients that registered the reviews are anonymous. The patients registering reviews to Legelisten.no had to be above 18-years old, have recently visited a dental practitioner, and have access to internet and the appropriate electronic equipment [Citation43]. The reviews contained a commentary section in which the patients had to write a free-text comment, and an obligatory overall satisfaction rating, as well as several specific closed-ended questions investigating the patients’ satisfaction in multiple areas. The terms and conditions of the website states that reviews that contain information about severe diagnostic mistakes and other severe incidents will be removed ahead of publication [Citation43]. Also, any reviews containing swearing, personal attacks, sexual or obscure language are filtered out before being published online. Thus, the data in this study does not contain such content.

Measurement of patient satisfaction

Patients indicated their satisfaction with a dental visit with a specific dental practitioner on Legelisten.no and provided ratings on 10 different aspects related to patient satisfaction. The 10 aspects were as follows: ‘Treatment Advice Rating’, ‘Treatment Comfort Rating’, ‘Treatment Result Rating’, ‘Service Availability Rating’, ‘Service Staff Rating’, Service Facilities Rating’, ‘Price Information Rating’, ‘Final Price Rating’, ‘Price Level Rating’ and ‘Overall Rating’. The aspect called ‘Overall Rating’ was used in this study as an indicator of whether a challenging encounter or a positive encounter had taken place. The other rating aspects were not used in this study. ‘Overall Rating’ was scored by the patients on a 5-point ordinal scale (visually represented as ‘stars’), where 1-star indicated low levels of satisfaction and 5stars indicated high levels of satisfaction. The scores were not normally distributed, with 5-star-reviews representing 90.3% (n = 10,627), 4-star reviews 3.0% (n = 350), 3-star reviews 0.9% (n = 100), 2-star reviews 1.6% (n = 183), and 1-star reviews 4.3% (n = 504). Nevertheless, there were sufficient reviews with 1-star or 2stars, and rich descriptions of the encounter, to conduct a thorough qualitative analysis.

Due to the amount of text material and scewed distribution of rating scores, two subsamples representing positive dental encounters (high patient satisfaction) and challenging dental encounters (low patient satisfaction) were drawn from the original dataset of 11,764 reviews. This process is visualised in , and resulted in two separate data sets of positive or challenging dental encounters. In order to randomise the selection of the reviews, all reviews in the two data sets received an unique id-number and a random sequence of the number ranges for each data set were generated by a random number generator (website Randomised.org). The first 50 numbers were used to draw the review sample from both sets of reviews, which provided 50 reviews representing a challenging encounter and 50 reviews representing a positive encounter. The patients’ reviews in the challenging encounter set contained a total of 3280 words. In the positive encounter set the patients had written a total of 2525 words. Each review had to contain at least 100 characters with no upper limit. The review length ranged from approximately 20 words to 300 words in both review sets.

Qualitative analysis

A thematic analysis was conducted to discover themes related to a positive encounter or a challenging encounter in the two sets of reviews [Citation44]. To ensure validation the steps 1–5 of the thematic analysis, illustrated below, was conducted independently by two of the authors. The results of the independent analyses were merged into a final product at the end of the study period (steps 6–8). The procedure of the thematic analysis was as follows:

Reading through the text material to get an overview of the content.

Specifically reading through each review while coding abstract cases.

The codes were rearranged and categorised into meaningful themes.

Re-reading through the text material to spot missing or uncomplete codes, and to re-evaluate the meaningfulness and interpretation of codes.

Interpreting possible connections and explanations of the importance of themes in relation to challenging encounters.

A group meeting, where the authors independent coding and formation of themes was discussed, which resulted in a re-arranging of themes and codes to best fit both authors’ views.

Writing up the themes and their explanation and connection to challenging encounters.

Additional group meetings for further evaluation of the interpretation of themes and their connections to challenging encounters. This step was repeated until all authors were satisfied with the results.

The process described resulted in a series of five main themes that the authors found to be related to the patients’ perception of a challenging or a positive encounter.

Results

Out of the 11,764 reviews at Legelisten.no, 5.8% were classified as describing challenging encounters, and 93.3% were classified as describing positive encounters. The geographic distribution is not available in our dataset due to anonymity, however, the publically available data from Legelisten.no shows that the reviews cover all regions of the country, but the number of reviews varies with the density of dentists and population density, i.e. more reviews in larger cities. The gender and age distribution of our sample is portrayed in .

Table 1. Age and gender distribution of reviewers and dentists in the total sample and subsample, for challenging and positive encounters.

It is worth noting that the sample provides few reviews of dentists aged 20–40 years, but more reviews of dentists aged 41–60+ years. Also, the patients writing most of the reviews were aged between 20 and 30 years, while fewer were aged below 20 or 41 years and above.

Thematic analysis

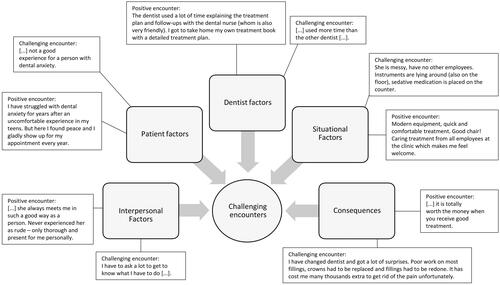

Patients’ experiences of a challenging encounter seemed closely related to the following themes identified from a thematic analysis of the reviews: (1) Interpersonal factors, (2) Patient factors, (3) Dentist factors, (4) Situational factors, and (5) Consequences. The themes with example quotes are represented in . Whether the encounter was perceived as challenging or positive relied upon the quality of the possible issues underlying the themes. In the following section the themes are further explained and detailed, with examples of how they were identified from the data as well as how aspects within a theme could contribute to the patients’ experience of a challenging encounter.

Figure 2. Presentation of themes and illustrative quotes. Each theme is illustrated with a quote representing a challenging encounter and a quote representing a positive encounter.

Interpersonal factors

The interpersonal factors concern how patients write about the relationship established with the dentist, as well as the perception of the dentists’ relational abilities. This theme of interpersonal factors might look similar to the theme ‘dentist factors’, in the sense that it is considering aspects around the dentist abilities. However, interpersonal factors are considered to be different in the way that they are a specific interpretation of the interaction between patient and dentist, while ‘dentist factors’ is a description of the patients’ perception of the dentists’ static personality traits, which might stem from other kinds of behaviour in the situation. The theme ‘interpersonal factors’ is concerned around how patients observe the dentists’ social behaviour and make up their mind about the quality of the established relationship. The aspects considered important here from the patients’ perspective were the quality of the communication, expressions of emotional competence and empathy. The patients in our sample assessed their dentist in several ways, while appearing to try to make sense of his/her relationship skills and/or competence. Patients experiencing their dentist to be empathic, and to be trustworthy or competent in the professional relationship, often perceived the encounter as positive. As in this example:

(1) I experience her as very competent, and she always meets me in such a good way as a person. Never experienced her as rude – only thorough and present for me personally.

The communication skills of the dentist were highly valued, as expected, and this was discussed by patients regularly:

(2) He tells you what he is going to do, and gives you several alternative treatment options at different price levels […].

There also appeared to exist an expectation that the dentist was the person in charge and responsible for the communication during treatment, more so than the patient. Several patients expressed that they wanted the dentist to be sociable and to explain the process of treatment, and reviews describing challenging encounters pressured the fact that the dentist was either uncommunicative, rude, or seemed uninterested in their wellbeing. See for example these quotes:

(3) Nonempathic. Yelled and made fun of me. Rough and short-tempered.

(4) I have to ask a lot to get to know what I have to do.

The dentist seems to be expected to have multiple abilities, i.e. to act professional and competent, as well as empathic and lovable. Whenever this was not the case, or the dentist displayed poor relationship skills, it would often lead to the patients experiencing the encounter as more challenging.

Patient factors

Patient factors stem from within the patients themselves, and are factors which might impact the patients’ assessment of the encounter as for instance challenging or positive. Patients may have specific expectations related to the dental encounter, often times influenced by previous experience with dental treatment, that may affect their view of the current visit and whereby the current visit is evaluated as either positive or negative:

(5) After suffering from dental anxiety for many years, I was recommended X when he worked in [Norwegian municipality]. I was treated in a good and respectful manner.

Patients who presented some underlying psychosocial issues were not uncommon, as was the case in this positive review:

(6) I have struggled with dental anxiety for years after an uncomfortable experience in my teens. But here I found peace and I gladly show up for my appointment every year.

Dental anxiety was also mentioned in reviews signalling challenging encounters. In some instances, pre-existing dental anxiety was reinforced by the challenging encounter, leading to a vicious circle of even more anxiety. As in these reviews:

(7) […] not a good experience for a person with dental anxiety.

(8) […] makes me nervous and insecure […].

In sum, the identified patient factors contributed to the patients’ experience of the encounter as either challenging or positive, by equipping the patient with certain prior knowledge and top-down expectations, which appeared to colour the present encounter.

Dentist factors

This theme concerns the patients’ perceptions of the personality or key characteristics of the dentist. Thus, it differs from the interpersonal factors, although there might be considerate amount of overlap between these themes.

It was observed that patients considered the work-ethic of the dentist very important, for instance that the dentist was expected not to be motivated by financial gain or to take unethical decisions in treatment planning or during treatment. Reviews related to positive encounters indicated that the dentist was found to be professional, competent, nice, and friendly. If the dentist took up too much of the patients’ time the patients indicated that they felt less satisfied, but it was also unsatisfactory if the dentist appeared stressed or in a hurry while treating the patients. These two quotes illustrate how the time spent could be viewed very different in a challenging encounter versus a positive encounter:

(9) […] used more time than the other dentist […]. (Challenging encounter)

(10) The dentist used a lot of time explaining the treatment plan and follow-ups with the dental nurse (whom is also very friendly). I got to take home my own treatment book with a detailed treatment plan. (Positive encounter)

These seemingly contradictory findings might be due to individual patients’ preferences or expectations about time management in dental treatment settings.

From the reviews describing challenging encounters it was found that the patients’ were more likely to percieve the encounter as challenging if the dentist displayed unfavourable attitudes or traits like aggression, disrespect and introversion.

(11) I perceive him as a rude and uncomfortable person.

In sum, the personality traits or key characteristics of the dentist seemed to be consistently assessed and reported as one of the most important issues related to the experience of a challenging encounter mentioned by the patients, especially if this personality resulted in the dentist showing negative social traits affecting the treatment situation negatively.

Situational factors

The aspects related to the clinic staff and the facilities of the clinic, as well as other issues concerning the surroundings were often mentioned in the reviews. There seemed to be a threshold where the surroundings did not matter if they were considered within the spectre of normality, for example related to expectations about how a dental clinic should be. Whenever the facilities or staff service fell below a threshold of normality, they were mentioned as something important and negative, but most often this would not in itself lead to the patients describing a challenging encounter. Moreoften the patients would mention other issues related to the challenging encounter as well, see for example this review:

(12) She is messy, has no other employees. Instruments are lying around (also on the floor), sedative medication is placed on the counter.[…] She also told me that a tooth that has been a little painful had to get root canal treatment. The pain went away on it own and my regular dentist told me that the tooth aboslutly did not need root canal treatment.

However, there were some exceptions where the facilities constituted the main reason why the patients were less satisfied with their visit, as described in this review:

(13) Worn-down waiting room, where should one hang ones coat? […] could also invest in a new operation lamp, as it sometimes worked and sometimes did not work.

If the service or facilities were high above the patients’ initial expectations, then it was mentioned as something positive:

(14) Modern equipment, quick and comfortable treatment. Good chair! Caring treatment from all employees at the clinic which makes me feel welcome.

In most cases the patients seemed unaffected if the facilities and service from staff was functioning and ‘good enough’ or as expected, and if they experienced a positive encounter. In those cases the facilities or staff could sometimes be mentioned in one simple positive sentence or with a few general positive words. Other times, when the situational factors fell below a threshold of perceived normality, or appeared simultaneously with other negative factors, it could lead to the patients perceiving the encounter as challenging.

Consequences

The aftermath of a challenging or positive encounter can be explored through the theme Consequences. Through this broad theme both the consequences for the patient, and the consequences for the dentist, are considered as expressed in the review. For the dentist, relevant consequences could for example be: Whether the patients expressed a desire to come back for another appointment, if the patients said they would recommend the dentist to others, and also whether the patients felt that they achieved better dental health from visiting their dentist. Especially important to the patients’ wellbeing might be whether there were any complications that had to be fixed later on by another dentist, or whether there were significant amounts of pain during or after treatment:

(15) I have changed dentist and got a lot of surprises. Poor work on most fillings, crowns had to be replaced and fillings had to be redone. It has cost me many thousands extra to get rid of the pain unfortunately.

Patients were preoccupied with several consequential matters and several reviews mentioned the consequences for the patients’ dental health. The reviews mentioned both positive and negative outcomes. When patients wrote about a positive encounter, they often mentioned pain relief, increased quality of dental health, and having positive memories of their treatment. In contrast, for the patients who indicated having experienced a challenging encounter, the memories from treatment included severe pain after and during treatment, worsening of dental health, more anxiety related to dental treatment, etc. See for example these reviews:

(16) The treatment was painful.

(17) I have never had dental anxiety, but I did not feel safe in her chair. Had to change dentist to get my tooth fixed properly, because she did not get it right after two tries.

The theme consequences is different from the other themes in the sense that the consequences could affect the patients’ perception of the encounter long after the treatment happened. Long term positive consequences would for example arguably leave the patient with more positive memories of the encounter than if long term consequences were negative, although the experience of the encounter in the present moment might have been more mixed or ambiguous, since the consequences might work as top down recall cues after the fact. In such cases, patients might remember encounters as more or less challenging than they really were based on long term consequences rather than aspects of the encounter itself.

Discussion

In this study, the aim was to investigate online reviews of dentists in order to map the key themes that characterise challenging encounters in dental practice from the patients’ perspectives, and to contrast these to the themes found in online reviews of positive encounters. The analysis identified a set of common themes for the patients describing either a positive or a challenging encounter, where the contrast appears to be not only the positive or negative aspects related to the themes, but also that the same aspects might be framed or experienced as either positive or negative depending on the patient. In the results section, the themes and how they could contribute to the patients’ view of the encounter were detailed. In the following discussion we would like to focus on the interpretation of the themes and their interaction.

Both interpersonal factors and the intrapersonal factors of the patients and the dentists, were interpreted as the most important contributors to the patients’ view of the encounter as challenging or positive. This is supported in previous research on online reviews written by patients [Citation1]. Previous research also supports the observation that past experiences influence patients’ view of the clinical encounter [Citation25,Citation34,Citation37,Citation38]. The current results show that the joint influence of the patients’ past experiences and the patients’ unique personalities might colour how different aspects of the treatment are perceived. Also, dentists’ personalities and personal traits would exerct influence in the clinical dental encounter, and could be interpreted as positive or negative based on patients’ preferences or experiences. Similarly, the situational aspects could alter patients’ experience and interpretation of the visit. A clean office with helpful staff would for example influence both the patients’ perceptions and thoughts about the clinical encounter in a positive manner, including the interpersonal relationship between the patient and the dentist. It appears that patients often engage in a form of top-down processing of the clinical encounter, where past experiences and current emotional state could influence their interpretation of the ongoing events. While the influence of top-down processing on perception in different situations are well documented in laboratory studies [Citation45,Citation46], the practical, clinical implications for challenging clinical encounters in dentistry might be less studied or well understood.

Some of the patients’ past experiences seemed to play a more important role than other experiences. Often, past experiences involving intense and aversive emotions, for instance experiences related to dental fear and anxiety, appeared to be strong contributors to how the patients came to view the present encounter. In the reviews of challenging encounters, patients sometimes described previous experiences with dental anxiety, which were reinforced by the present encounter. Some patients also claimed that they had developed dental anxiety, or had felt very afraid and uncomfortable, during or as a result of the encounter that they wrote about in the review. In contrast, dental anxiety also became a topic in the positive reviews, by which anxious patients described the dentist as being very skilled in creating a safe and trusting environment, for instance by explaining the treatment procedures. Dental anxiety is quite common in the adult population. High prevalences of are reported in recent studies from Saudi Arabia and Tanzania with repectively 80% [Citation47] and 87% [Citation48], while lower but substantial prevalences are reported in both Europe and the USA [Citation49–51]. In light of this, it was not suprising that dental anxiety featured frequently in the reviews. Overall, dental anxiety seemed to be a very common and important emotional state within the patients, and dentists should be trained in identifying and accommodating anxious patients.

Whenever there was a substantial mismatch between the patients’ needs and understanding of the situation and the dentists’ behaviour, the resulting encounter would be perceived as challenging. This is also found in previous research [Citation11–15]. Such challenges could be related to a failure in detecting and understanding the patients’ inner emotional states. Previous studies have found that the dentists often fail to detect whenever the patient is not satisfied with the treatment [Citation34], and also that dissatisfied patients are a highly diverse group [Citation3]. Emotional competence is often defined as one’s capacity to detect and relate to other peoples’ emotions, and to use and regulate one’s own emotions in a useful manner to guide one’s actions [Citation52,Citation53]. The findings of this study emphasises the need for dentists to develop good communication skills and emotional competence in order to correctly interpret their patients’ needs in the treatment setting and to solve possible issues. Furthermore, the communication skills utilised by the dentists need to be flexible and dynamic, rather than a static, ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach, in order to accommodate different patients’ needs, personality styles, and preferences. Past research has shown positive effects from implementing training programs for improving emotional competence and communication skills in health professionals [Citation54–56], and participating in these training courses might help dentists minimise stress from challenging encounters [Citation57].

When exploring the online reviews included in this study, one of the key questions is how patients’ perceptions of treatment success or failure impacts perceptions of other aspects of the clinical encounter, and vice versa. Theories from behavioural and psychological research could provide answers, as this potentially could involve automatic causal inference of events. In social psychology, attribution theory describes how persons might find causes for the behaviour of others [Citation58,Citation59]. Recent studies have shown that the causal attributions made by healthcare professionals concerning their patients affect the strategies they choose when interacting with the patients [Citation60,Citation61]. Another tendency described in attribution theories is that the behaviour of others is often attributed to the stable characteristics of others, while the behaviour of oneself is thought to be due to changeable events outside onés control [Citation58,Citation62]. In the current context this might imply that patients tend to think that flaws resulting from treatment is due to how that dentist is as a person, rather than caused by bad luck, faulty equipment or materials, or other random and external one-time events. That being said, it is natural to place the responsibility of the results of dental treatment in the hands of the dental health professional, and this would hardly qualify as an attribution bias. However, the findings point to a tendency of the patients to link the flaws in the communication to their perception of some stable personality traits of the dentist, and to discount both their own contribution to the communication and the possibility that the dentist might behave differently in the future. Although it is not the aim of this study, it would be interesting to further investigate how the causal attributions of the patients could influence their perceptions of the encounter. In any case, dentists would benefit from being aware of the patients’ attribution of causes for the challenging encounters, and try to develop methods to better handle challenging situations with patients.

Strengths and limitations

There are some limitations in this study that should be discussed. Firstly, the sample of reviews received from Legelisten.no should be considered a convenience sample. We do not know how often and to what extent the moderators of Legelisten.no filter out the reviews ahead of publication. The age distribution could not be said to be representative of the general patient population in Norway, as both our total sample and sub-samples contained few reviews from patients aged 60+ and under 20 years old. Also, the age distribution in the subsamples were similar to that of the total sample (). The total sample did not contain any reviews made by patients aged 18 years and younger since the website requires users to be above 18 years of age. In addition to this, a large part of the reviewers chose to not report their age and gender, especially if satisfaction was low (1–2 stars). As in other qualitative studies, the representativity is limited to similar conditions, and the findings should be handled accordingly.

Secondly, regarding the trustworthiness of the analysis, the authors have made an effort to produce as reliable and valid results as possible. This was done by following a common analysis approach, arranging group discussions and practicing reflexivity throughout the research process. Considering researchers’ bias, the authors would like to add that although all efforts have been made to produce credible results, as in all qualitative research we also have some experiences and underlying presumptions which might interfere in the analytic process. Although this might be the case, the process of discussing the results and analysis in group settings, aims to correct personal biases and to level out possible dissimilarities between the different authors’ perspectives.

Lastly, the recieved sample contained a high amount of positive reviews, with 90% of the reviews representing a 5-star rating. While previous research suggest that the majority of online reviews of healthcare providers are positive [Citation1,Citation4,Citation63], there is a possibility that dentists that perceive a patient as being satisfied are more likely to encourage that patient to write a review of the experience. Also, it might be possible that some patients are not aware that they could write an online review of their dentist, or may chose not to for various reasons. However, the selection process used in this study would help to minimise this issue in the current analysis.

Albeit some limitations, this study could contribute to fill a gap in this field of research, as there are few studies conducted on online reviews of dentists. The strength of this study lies in its focus on the patients’ perspective, providing feedback directly from patients not provided from a traditional questionnaire or interview. Recently, the usefulness of online reviews have been confirmed through studies comparing the use of traditional methods of assessing patients’ experience of health care [Citation64]. Online reviews can be argued to provide an unfiltered view of the patients’ perspectives, while traditional interviews and questionnaires provide answers to questions predetermined by the health professionals conducting the studies. Also, dental students have reported the usefulness of receiving patient feedback in training to help improve their communication skills [Citation65]. The aim to provide patient centred care in dentistry could thus be reached through investigating online reviews and discovering potential areas in need of improvement. This article provides a new perspective on the factors related to the patients’ perspective of challenging encounters, through investigating patient written online reviews.

Conclusions

The patients’ perspectives of, and satisfaction with, the clinical encounter is influenced by their past experiences, the situation, their interpretation of the dentist, the quality of the dentist-patient relationship and the consequences of treatment. Furthermore, dental patients tend to perceive the challenging encounter to be a result of the dentists’ personality traits and communication skills, and challenging encounters seem to indicate a mismatch between the patients’ expectations of the situation and the actual situation. It does not seem to be one uniform way of acting to prevent challenging encounters, rather, dentists need to be able to shift between different communication styles in order to adapt to the personality and preferences of the patients. Dentists should be encouraged to work towards developing their emotional competence and dynamic communication skills to better detect and follow up on patients’ needs and expectations in the treatment setting.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this article would like to acknowledge Legelisten.no for providing the data used in this study, and for providing patients with the opportunity to post reviews of their dental treatment experiences in an open, online forum.

Disclosure statement

The authors have stated explicitly that they have no conflicts of interest writing this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- López A, Detz A, Ratanawongsa N, et al. What patients say about their doctors online: a qualitative content analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(6):685–692.

- Lin Y, Hong YA, Henson BS, et al. Assessing patient experience and healthcare quality of dental care using patient online reviews in the United States: mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(7):e18652.

- Zhang W, Deng Z, Hong Z, et al. Unhappy patients are not alike: content analysis of the negative comments from China’s Good Doctor website. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(1):e35.

- Hong YA, Liang C, Radcliff TA, et al. What do patients say about doctors online? A systematic review of studies on patient online reviews. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(4):e12521.

- Schlosser AE. Self-disclosure versus self-presentation on social media. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;31:1–6.

- Suler J. The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7(3):321–326.

- Widmer RJ, Maurer MJ, Nayar VR, et al. Online physician reviews do not reflect patient satisfaction survey responses. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(4):453–457.

- Khasawneh A, Ponathil A, Firat Ozkan N, et al. How should I choose my dentist? A preliminary study investigating the effectiveness of decision aids on healthcare online review portals. Proc Hum Factors Ergon Soc Annu Meeting. 2018;62(1):1694–1698.

- Lorenzetti RC, Jacques CM, Donovan C, et al. Managing difficult encounters: understanding physician, patient, and situational factors. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(6):419–425.

- Mota P, Selby K, Gouveia A, et al. Difficult patient-doctor encounters in a Swiss university outpatient clinic: cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e025569.

- Chipidza FE, Wallwork RS, Stern TA. Impact of the doctor-patient relationship. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(5):10.

- Elder N, Ricer R, Tobias B. How respected family physicians manage difficult patient encounters. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):533–541.

- Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounters in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(10):1069–1075.

- Katz A. How do we define “difficult” patients? Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(6):531.

- Adams M, Maben J, Robert G. ‘It’s sometimes hard to tell what patients are playing at’: how healthcare professionals make sense of why patients and families complain about care. Health (London). 2018;22(6):603–623.

- Hull SK, Broquet K. How to manage difficult patient encounters. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14(6):30–34.

- Blackall GF, Green MJ. “Difficult” patients or difficult relationships? Am J Bioeth. 2012;12(5):8–9.

- Bodner S. Stress management in the difficult patient encounter. Dent Clin North Am. 2008;52(3):579–603.

- Hinchey SA, Jackson JL. A cohort study assessing difficult patient encounters in a walk-in primary care clinic, predictors and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(6):588–594.

- Goetz K, Schuldei R, Steinhäuser J. Working conditions, job satisfaction and challenging encounters in dentistry: a cross-sectional study. Int Dent J. 2019;69(1):44–49.

- Myers H, Myers L. It’s difficult being a dentist’: stress and health in the general dental practitioner. Br Dent J. 2004;197(2):89–93.

- Choy H, Wong M. Occupational stress and burnout among Hong Kong dentists. Hong Kong Med J. 2017;23(5):480–488.

- Collin V, Toon M, O’Selmo E, et al. A survey of stress, burnout and well-being in UK dentists. Br Dent J. 2019;226(1):40–49.

- Chapko MK, Bergner M, Green K, et al. Development and validation of a measure of dental patient satisfaction. Medical Care. 1985;23:39–49.

- Afrashtehfar KI, Assery MK, Bryant SR. Patient satisfaction in medicine and dentistry. Int J Dent. 2020;2020:6621848.

- Faezipour M, Ferreira S. A system dynamics perspective of patient satisfaction in healthcare. Procedia Comput Sci. 2013;16:148–156.

- Naidu A. Factors affecting patient satisfaction and healthcare quality. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2009;22(4):366–381.

- Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804.

- Plewnia A, Bengel J, Körner M. Patient-centeredness and its impact on patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes in medical rehabilitation. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):2063–2070.

- Zimmerman RS. The dental appointment and patient behavior. Differences in patient and practitioner preferences, patient satisfaction, and adherence. Med Care. 1988;26(4):403–414.

- Bos A, Vosselman N, Hoogstraten J, et al. Patient compliance: a determinant of patient satisfaction? Angle Orthod. 2005;75(4):526–531.

- Li W, Wang S, Zhang Y. Relationships among satisfaction, treatment motivation, and expectations in orthodontic patients: a prospective cohort study. Patient Preference Adherence. 2016;10:443–447.

- Chapple IL, Bouchard P, Cagetti MG, et al. Interaction of lifestyle, behaviour or systemic diseases with dental caries and periodontal diseases: consensus report of group 2 of the joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:S39–S51.

- Riley IIJ, Gordan VV, Hudak-Boss SE, et al. Concordance between patient satisfaction and the dentist's view: findings from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(4):355–362.

- Jones L, Huggins T. Empathy in the dentist-patient relationship: review and application. N Z Dental J. 2014;110(3):98–104.

- Sachdeo A, Konfino S, Icyda RU, et al. An analysis of patient grievances in a dental school clinical environment. J Dental Educ. 2012;76(10):1317–1322.

- McCrea SJJ. An analysis of patient perceptions and expectations to dental implants: is there a significant effect on long-term satisfaction levels? Int J Dent. 2017;2017:8230618.

- Colvin J, Dawson DV, Gu H, et al. Patient expectation and satisfaction with different prosthetic treatment modalities. J Prosthodont. 2019;28(3):264–270.

- Nair R, Ishaque S, Spencer AJ, et al. Critical review of the validity of patient satisfaction questionnaires pertaining to oral health care. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46(4):369–375.

- Sacristán JA, Aguarón A, Avendaño-Solá C, et al. Patient involvement in clinical research: why, when, and how. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:631–640.

- Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. The Lancet. 2009;374(9683):86–89.

- Legelisten AS. Om oss 2012. [cited 2020 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.legelisten.no/om-oss.

- Legelisten AS. Vilkår [Web Page]. Legelisten.no: Legelisten AS; 2012. [cited 2020 Oct 16]. Available from: https://www.legelisten.no/vilkar.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Niedenthal PM, Wood A. Does emotion influence visual perception? Depends on how you look at it. Cogn Emot. 2019;33(1):77–84.

- Gordon N, Tsuchiya N, Koenig-Robert R, et al. Expectation and attention increase the integration of top-down and bottom-up signals in perception through different pathways. PLoS Biol. 2019;17(4):e3000233.

- Al Dhelai TA, Al-Ahmari MM, Adawi HA, et al. Dental anxiety and fear among patients in Jazan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2021;22(5):549–556.

- Musalam K, Sohal KS, Owibingire SS, et al. Magnitude and determinants of dental anxiety among adult patients attending public dental clinics in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania. Int J Dent. 2021;2021:1–7.

- Svensson L, Hakeberg M, Boman U. Dental anxiety, concomitant factors and change in prevalence over 50 years. Commun Dent Health. 2016;33:121–126.

- White AM, Giblin L, Boyd LD. The prevalence of dental anxiety in dental practice settings. Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2017;91(1):30–34.

- Nicolas E, Collado V, Faulks D, et al. A national cross-sectional survey of dental anxiety in the French adult population. BMC Oral Health. 2007;7(1):12.

- Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence. Imagination Cogn Pers. 1990;9(3):185–211.

- Sa B, Ojeh N, Majumder MAA, et al. The relationship between self-esteem, emotional intelligence, and empathy among students from six health professional programs. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(5):536–543.

- Khalifah AM, Celenza A. Teaching and assessment of dentist-patient communication skills: a systematic review to identify best-evidence methods. J Dent Educ. 2019;83(1):16–31.

- Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Asai M, et al. Effect of communication skills training program for oncologists based on patient preferences for communication when receiving bad news: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(20):2166–2172.

- Flowers LK, Thomas-Squance R, Brainin-Rodriguez JE, et al. Interprofessional social and emotional intelligence skills training: study findings and key lessons. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(2):157–159.

- Ruiz-Aranda D, Extremera N, Pineda-Galán C. Emotional intelligence, life satisfaction and subjective happiness in female student health professionals: the mediating effect of perceived stress. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(2):106–113.

- Weiner B. Attribution theory. In: Järvelä S, editor. Social and emotional aspects of learning. Oxford (UK): Elsevier Ltd.; 2010. p. 9–14.

- Manusov V, Spitzberg B. Attribution theory. In: Baxter LA, Braithewaite DO, editors. Engaging theories in interpersonal communication: multiple perspectives. New York (NY): Sage; 2008. p. 37–49.

- Golfenshtein N, Drach-Zahavy A. An attribution theory perspective on emotional labour in nurse-patient encounters: a nested cross-sectional study in paediatric settings. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(5):1123–1134.

- Bsharat S, Drach-Zahavy A. Nurses’ response to parents’ ‘speaking-up’ efforts to ensure their hospitalized child’s safety: an attribution theory perspective. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(9):2118–2128.

- Ross L. From the fundamental attribution error to the truly fundamental attribution error and beyond: my research journey. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2018;13(6):750–769.

- Black E, Thompson L, Saliba H, et al. An analysis of healthcare providers’ online ratings. Inform Prim Care. 2009;17(4):249–253.

- Ranard BL, Werner RM, Antanavicius T, et al. Yelp reviews of hospital care can supplement and inform traditional surveys of the patient experience of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(4):697–705.

- Coelho C, Pooler J, Lloyd H. Using patients as educators for communication skills: exploring dental students’ and patients’ views. Eur J Dent Educ. 2018;22(2):e291–e299.