Abstract

Objective

Opioid maintenance treatment (OMT) patients in Norway are eligible for free oral healthcare services; however, oral health morbidity remains high and the uptake of services among this patient group is low. As knowledge of the reasons for the low uptake of services among OMT patients is insufficient, this study adopted a qualitative approach to explore this from the perspectives of patients and dental healthcare workers (DHWs).

Material and methods

Through focus group and individual interviews, data were collected from 63 participants: 30 patients receiving OMT and 33 DHWs. Key themes were identified through a thematic analysis.

Results

Teeth were a significant factor in OMT patients’ quality of life and recovery. Accompaniment to scheduled dentist appointments was identified as a facilitator by both the patients and the DHWs. The dentist-patient relationship was also seen as an important facilitator of dental treatment; DHWs with previous experience of treating OMT patients were valued by patients because of their high verbal and non-verbal communication.

Conclusions

Helping OMT patients attend dental appointments, improving the dentist-patient relationship, and expanding stakeholders’ knowledge of OMT patients’ right to oral healthcare services may increase the uptake and benefits of dental healthcare services among OMT patients. The current support framework within the OMT system has the potential to increase the communication and efficiency of dental healthcare services available to patients undergoing OMT.

Background

Substance use disorders (SUD) are associated with a range of unfortunate health outcomes including overdose deaths and early mortality, chronic infections, pulmonary diseases, and oral health problems [Citation1,Citation2]. While oral health problems have received some attention in the substance use literature [Citation2–4], research on people receiving opioid maintenance treatment (OMT) in different contexts is relatively scarce. People with SUD and individuals receiving OMT have poorer oral health than their comparably aged counterparts [Citation2,Citation5,Citation6]. Whereas adequately functional dentition is defined as having 20 well-distributed teeth [Citation7–9], the average number of functional teeth among people with SUD is typically fewer than 20 [Citation10,Citation11]. Studies have also shown that more than half of OMT patients are dissatisfied with the appearance of their teeth and mouth [Citation12] and that they suffer impaired oral health-related quality of life [Citation11,Citation13].

Since 2005, in Norway, people with SUD and patients receiving OMT have been included in public dental healthcare services’ priority list of groups entitled to free oral healthcare [Citation13,Citation14]. Approximately 8100 people in Norway are receiving OMT [Citation15]. However, OMT patients are in the lowest priority group [Citation16]. (The full guidelines can be found in [Citation17].) Although they are entitled to free dental healthcare, knowledge of the use of these services among OMT patients is insufficient [Citation13]. Recent figures suggest that service use is limited; only 42% of OMT patients report visiting a dentist annually [Citation11] compared with an annual dental attendance of between 65% and 76% in the general adult Norwegian population [Citation18]. Research on the use of dental services has primarily focussed on the barriers faced by patients undergoing OMT. These barriers include homelessness, continued substance use, low self-confidence, the poor acceptability of services [Citation3], financial difficulties [Citation19,Citation20], self-medication to avoid withdrawal symptoms, dental phobia, low pain tolerance, expressed anxiety, repeated trauma during dental treatment, and additional challenges in life [Citation2,Citation3]. Although these barriers are important, research on what facilitates the use of oral healthcare services among people receiving OMT remains lacking.

Avoiding or neglecting oral healthcare services can lead to poor oral health, which in turn may lower a person’s social relationships and quality of life [Citation13]. This relates to research suggesting that treatment of oral diseases can play an important role in OMT participants’ construction of a new identity [Citation3]. According to an Australian study [Citation21], patients at an alcohol and drug treatment facility reported concerns about their dental appearance and wanted ‘good teeth’. Having good teeth was linked to higher confidence, self-esteem, opportunities in life, and interest in information and advice on oral health. The importance of dental treatment for people with SUD was also emphasised in a Norwegian study in which 57% were very dissatisfied with the appearance of their mouth/teeth and 92% considered the offer of dental treatment to be very significant for them [Citation13].

The present qualitative study builds on two previously conducted quantitative studies (TANNKLAR 1 and 2) conducted among dental health workers (DHWs) and patients undergoing OMT in western Norway. TANNKLAR 1 and 2 focussed on the oral health situation and experiences of using dental healthcare services among OMT patients (TANNKLAR 1 [Citation22]) and DHWs’ attitudes towards and experience of treating patients receiving OMT (TANNKLAR 2 [Citation12,Citation23]). These studies showed that the majority of OMT patients were dissatisfied with their oral health and experienced a reduced quality of life due to their oral conditions. Further, 76% of dentists and only 24% of dental hygienists treat OMT patients on a monthly basis [Citation23]. Based on these previous studies, the purpose of the current study was to examine the factors facilitating OMT patients’ use of dental healthcare services as well as the factors allowing DHWs to provide dental healthcare services to OMT patients.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in eight OMT outpatient units and four oral health clinics in Bergen, Norway. Bergen has 283,930 inhabitants, of which approximately 900 receive OMT [Citation24]. The oral health clinics were located in all eight districts of Bergen, with each clinic responsible for providing services to the population of one or more districts. The county council of Vestland prioritises free dental care for OMT patients, and patients’ dental care is assessed against disease severity and treatment benefit as well as whether that benefit is proportional to the cost.

To understand DHWs’ perspectives and OMT patients’ facilitators in dental healthcare services, the research team chose a qualitative approach with focus group interviews followed by individual interviews. It designed semi-structured interview guidelines to conduct the focus group and individual interviews with both groups. The interview guides covered the following topics for OMT participants: perceptions of oral healthcare needs, attitudes towards and beliefs about adequate dental healthcare, and facilitators of and barriers to adequate healthcare. Examples of the questions were as follows: How do you feel about your teeth? How was your experience at your last visit to the dentist? How do you think DHWs think and feel about you and other OMT patients? The interview guide for DHWs covered the experiences of and attitudes towards providing dental care to OMT patients as well as the facilitators of and barriers to providing dental care to OMT patients. Examples of the questions were as follows: What is your experience of treating OMT patients/people with SUD? Have you ever experienced communication issues when working with OMT patients as a group? Do you have any suggestions about how to increase the chances of OMT patients using dental healthcare services? Clarifying questions were asked during the interviews to obtain a deeper and more coherent story.

Participants

A total of 63 individuals participated in this study: 30 OMT patients and 33 DHWs. Five focus groups were conducted (6–8 participants) with 27 OMT patients and four focus groups were conducted with 29 DHWs. Dentists, dental hygienists, and dental secretaries employed at the four public dental health clinics with the highest proportion of OMT patients were recruited for the focus group interviews. The majority of DHW participants were dentists (28 women and five men). Dental hygienists were not heavily represented, as they had minimal contact with OMT patients. On average, DHWs had 9.6 years of experience in treating OMT patients, ranging from two months to 15 years.

The sample of the OMT participants consisted of 19 men and 11 women. The selection of the sample included a range of experiences with the OMT program; time in treatment ranged from two months to 21 years. In addition, individual interviews were conducted with three OMT patients, with five–15 years of experience receiving OMT, and four DHWs, with four–15 years of experience in treating OMT patients.

Data collection and procedure

Between November 2019 and January 2020, data were collected through focus group interviews and individual interviews with the OMT patients and DHWs separately. A written informed consent form outlining the study details, the confidentiality of the provided information, and participants’ right to withdraw from the study was sought before conducting the focus group and individual interviews.

Research nurses working at the OMT outpatient clinics and staff at two local SUD care centres helped recruit the OMT patients for the focus group interviews. A snowball sampling approach in which the focus group participants were asked if they knew someone who would be interested in participating was used to recruit the participants for the individual interviews with both the DHWs and the OMT patients. None of the focus group participants were interviewed individually to maximise the sample of participants within the assigned study period and avoid repetition from individual participants.

The DHWs recruited for the focus group interviews were compensated for their estimated loss of hourly income and the OMT participants were compensated for their study participants with a NOK 200 gift card (worth approximately €19). The focus group interviews were conducted at the dental clinics and lasted 45–60 min. The individual interviews were conducted in a private space and lasted 30–45 min.

Two researchers with experience in qualitative methods were recruited to conduct the individual and focus group interviews. None of the researchers specialised in clinical treatment or the general field of oral health; thus, they also had no relationships with the participants before the interviews. The focus group and individual interviews were conducted in Norwegian and transcribed verbatim by the researchers before they translated them into English. The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (No. 59417).

Data analysis

The analysis was performed by the researchers who collected the data. The analysis process was a bottom-up, data-driven process in which inductive thematic analysis was used to identify, analyse, and report the main themes [Citation25]. Those data are relevant to the research questions and show repetitive response patterns were chosen as the themes [Citation25]. This approach allowed the researchers to answer the research questions as well as identify other themes that appeared as a result of the broader and spontaneous discussions during the focus group and individual interviews.

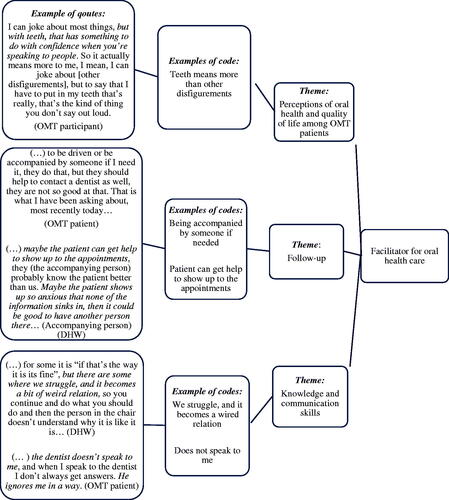

During the data collection period, the researchers met regularly to discuss their perceptions of the recurring themes identified in the focus group and individual interviews. When the researchers determined that no new themes were arising in the interviews, they agreed to stop the data collection. Thereafter, they familiarised themselves with the data by listening to and reading all the transcripts. Based on their analysis, they independently identified the dominant themes and developed code descriptions. When the initial coding had been completed, they compared and discussed their respective codes. The consensus was reached by consolidating related themes and removing or recoding others. In addition, to ensure that no aspects were overlooked during the process, codes and themes were discussed with other experienced researchers with knowledge of the fields of odontology and SUD. A final codebook was applied to the data and NVIVO 12 [Citation26] was used to generate the main categories and subcodes. illustrates the analysis process.

Results

Themes

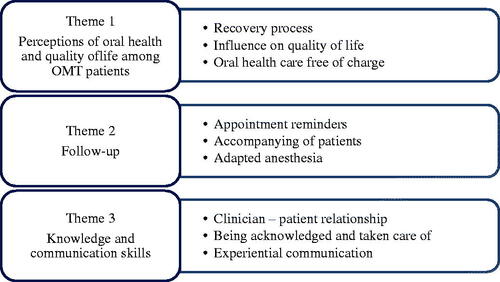

The results, related to the facilitators identified in this analysis, were extracted by the researchers. Following the thematic analysis, three themes with nine sub-themes were identified (see ).

Perceptions of oral health and quality of life among OMT patients

Recovery process

Teeth were significant in the participants’ recovery process due to their facial appearance and its impact on how they are perceived. Enrolment in OMT meant that several participants could address their oral health issues. Poor oral health negatively affects both mental and physical health, self-esteem, and quality of life. The importance of oral health and teeth was a driving motivation for them to use oral health services, as the quotes below illustrate.

A friend of mine, he only had two teeth in the front, he looked like a rat. I followed him to the dentist the day he was going to get his new teeth and he started crying, because being able to see someone smiling at you, for example, a girl, and being able to smile back… it does something with your quality of life. (focus group (FG) OMT, male)

Influence on quality of life

The DHWs often pointed out, unprompted, that the OMT patients were more grateful for the treatment they received, presumably because of the extremely poor dental status of many of them, and hence the significance that their teeth had in their everyday life. In this context, a DHW expressed:

(…) and if you’ve started with a completely broken down set of teeth, which does not look nice, and it ends up in a completely normal and functioning set of teeth, and that joy that you see, and the self-worth they suddenly get back… (individual interview (II) DHW)

The OMT patients had different experiences of visiting dentists and the treatment they had received. However, several participants were satisfied with their last visit to a dentist. This was highlighted by an OMT participant:

(…) I think the last time I got new teeth was in 2014 or 2016. (…) I used glue before [for the teeth], but I don’t use that anymore, they sit in place on their own. I can yell and shout as much as I like. I can cough. I was getting off the bus the other day and there was a guy in front of me who coughed, and he coughed out his whole top tooth prosthesis [followed by laughter]. (II, OMT)

Oral healthcare being free of charge

In light of the poor financial situation of many OMT patients, the fact that dental check-ups and treatment were free of charge was an important motivator, as was highlighted by one OMT participant:

(…) it was the main reason for starting OMT, the free oral healthcare. (…) Of course, it was okay to get the OMT medication to calm the extensive substance use I had, but the main reason was the dentist; it was to get my teeth fixed because I did not see any opportunity to get a job until I had fixed them [the teeth]. (FG OMT, male)

Oral health is vital to participants undergoing OMT. Free dental healthcare services were considered, both by the patients and the DHWs, as important, particularly for this group of patients, to help them benefit from this offer.

Follow-up

Appointment reminders

Although many of the OMT participants in this study had a strong desire to fix their teeth, some lived disorganised lives with a lack of housing, ongoing substance use, and cognitive issues due to years of substance use, which made it difficult to maintain control of daily routines and appointments. Others highlighted anxiety and dental phobia as reasons for avoiding oral healthcare services. Therefore, several of the participants expressed the need for help in maintaining their oral health, which the DHWs also highlighted as significant. In general, patients were responsible for remembering their dental appointments; however, some of the dental health clinics have established a short messaging service (SMS) reminder system that notifies patients of their appointments one day in advance. Some also call their patients to remind them of the appointment on the same day, as one OMT participant said:

(…) my dentist calls all the time. It is always blinking on my phone, two days before, then the same day… (FG OMT, male)

Some of the participants stated that these SMS reminders were helpful, as it meant that they showed up to the appointments and had less dropout from treatment compared with what they would have had without the reminders.

Accompanying patients

Having someone to accompany the OMT participants to the dentists, either family members or representatives from the support services was emphasised as important for participants not only to attend the clinic but also to maintain treatment follow-up and complete the treatment. The DHWs often reported that interrupted treatments because of dropping out were a major barrier to successful treatment. One OMT participant said:

(…) she [the OMT counsellor] called and got an appointment on a date where she could drive me and that got me started. Because I could have risked cancelling that appointment if I had had a bad day or something, so it meant a lot that she did drive me and got me there the first time, and after that I have gone by myself. (II, OMT)

The DHWs also recognised that being followed to the dentists was of value for OMT patients, especially since many had a dental phobia. In addition, OMT patients could have a backup in the treatment room or waiting room. The DHWs also highlighted that it was useful if the patients were followed by OMT staff, as this could open up alliance-building, as one DHW explained:

They [OMT patients] should have someone who accompanies them from OMT, well definitely the first time, so that we can see the current situation, and then we have a person we can contact in case of any problems. (II, DHW)

In addition, the DHWs were supportive of the possibility of increasing support to patients, as this helped them provide better care (i.e. completed treatments).

Adapted anaesthesia

The OMT participants generally reported a high level of anxiety and/or dental phobia; therefore, technological development in oral treatment and the types of anaesthetics offered to patients could facilitate treatment. Indeed, the OMT participants expressed that today’s process of anaesthesia such as the use of pre-anaesthetics, variety of anaesthetics, thinner needles, and dentists being better at administering anaesthesia influenced their dental experience positively. An OMT participant conveyed:

(…) I was given anaesthesia when I needed it, and we tried our best and they [dentists] have so much new equipment now that I was actually very surprised when they could do a lot without hurting… (FG OMT, male)

However, from the perspective of the DHWs, there was a concern about the administration of medications that could trigger opioid addiction. Thus, the majority of dentists did not administer addictive medications such as anaesthesia. Based on individual assessments, some dentists reported administering tranquillisers such as diazepam (Valium) as one of the anaesthetic approaches, as described below:

(…) I mean those under OMT should not get something that can awaken old memories to speak. Now that I think of it, ‘Oh, I have so much bloody pain and the paracetamol does not help, can I have 20 Paralgin forte [codeine/paracetamol-based medication]’?, that comes up again and again (…) well they can have 2 Valium [diazepam] but not 20 (…) that’s because they need it, well they don’t get any affect [triggers no addiction] if I give 2 Valium. (FG DHW, male)

Having a system for reminding OMT patients about their dental appointment, having someone accompanying them to the appointment, and the opportunity for anaesthetics adapted to the situation were viewed as measures that helped the patients attend and endure the treatment.

Knowledge and communication skills

Clinician–patient relationship

Both the DHWs and the OMT patients highlighted the importance of communication and the clinician-patient relationship. According to the DHWs, the way they spoke to OMT patients was significant for their relationship with the patient. The establishment of trust between patients and DHWs could affect the future course of treatment, as conveyed by one DHW:

I feel that when first meeting a patient, there is often a bit of aggression, high expectations, and demands, and they may think that the first time we look down on them. However, when we start talking and explaining, they become very grateful and appreciative, and they feel that we want to help and do the best for them. (FG DHW, female)

Another DHW expanded on this and conveyed:

I must use time to build trust by speaking to them and figure out where the fear [dental phobia/fear] comes from, or that bad feeling you have (…) What do you feel before you come here and when you sit here? Is there anything particular you are scared of and is there anything I can do to make you feel better? You explain to them as you go along. It’s a matter of building trust so they understand that when I do something, it’s because you are allowing me to do it and if you want me to stop, then I will… (II, DHW)

These results illustrate the importance of communication skills. DHWs must communicate with the patient to understand the patient and their previous experiences during dental treatment. Further, they must be aware of patients’ possible dental fear/anxiety as well as any unrealistic expectations about the type of treatment to which they are entitled (e.g. implant vs. denture). Communication in these situations requires skilled DHWs with knowledge of the patient group.

Being acknowledged and taken care of

Many of the OMT participants were satisfied with how they were met at the dental clinic and those with positive encounters highlighted that dentists met their needs, for example, to minimise their pain, which gave them a sense of security and confidence in DHWs. In addition, the participants expressed that being acknowledged and taken care of played a role in whether they completed the treatment. This was also highlighted by DHWs:

(…) they [OMT patients] appreciate that you take them seriously when they say they are actually in pain, that they are scared, that you don’t trivialise that the feelings are real, and that they are not dramatising. They appreciate that, to be believed. (II, DHW)

Furthermore, the majority of the OMT participants were expected to be treated as ‘regular’ patients rather than OMT patients. When asked if they felt they were met in the same way as other patients, several participants affirmed this, stating that DHWs’ way of meeting OMT patients influences their experience of dentistry.

Experiential communication

Whereas the OMT participants emphasised the importance of safety and being treated like other patients, the DHWs highlighted the significance of how they communicated with OMT patients. According to the DHWs, the first meeting with OMT patients could be challenging, as such patients can be an unpredictable group to treat. Furthermore, DHWs received no specific training on how to deal with OMT patients during their studies; therefore, their knowledge of how to communicate with them was mainly gained through their experience. The following quote from a DHW illustrates how to communicate with patients undergoing OMT:

Some just want to get the job done and leave. Others want a lot of information, so we talk them through everything; now we have a matrix on the tooth, now we are cleaning, now we are rinsing the tooth, now we are putting on the glue, and now we must dry it. We detail what we are doing the whole time. Some want to see in the mirror, they feel safe by doing that. It’s very different, so you have to just find out how they are and how can I work with them, because we never know [in advance]. (FG DHW, female)

An example of DHWs’ communication skills can be illustrated by the following response from a DHW to the question of how they communicated that patients could not have a given treatment such as implants:

Very often, these conversations come up in the first times that we meet, and then I don’t know the person very well and you have to probe what preferences the other person has, like you do with all people. (…) Can they handle that I am very direct or should I be more discreet? But sometimes it’s not very smart to be indirect, I mean we have to be direct about this; otherwise, there’s definitely going to be confusion. (FG DHW, female)

The OMT patients also highlighted the importance of DHWs’ communication skills and how they guided and explained the procedure. In this context, one OMT participant said:

She [the dentist] explains everything so that I understand it. ‘Now we are doing this, then we are doing that’. That’s what’s so nice about her, she explains everything so that I get it. She is just marvellous; all dentists should be like her. (II, OMT)

As these quotes show, both the OMT patients and the DHWs emphasised that DHWs’ communication skills and/or style influences OMT patients’ experiences of dental treatment. DHWs have a better possibility of being flexible and adjusting the treatment according to the patient’s expressed need by having knowledge and experience of OMT patients.

Discussion

This qualitative study offers unique information by focussing on the facilitators of OMT participants’ use of oral healthcare services, as provided by both DHWs and OMT patients. Highlighting the facilitators of the use of dental healthcare for this group of patients is rare in the literature. Previous studies usually separately examine the DHW or OMT perspective, which can lead to a loss of valuable insights. The current study addresses this gap in the body of knowledge, as it reveals the general agreement between DHWs and OMT patients, which encourages OMT patients to use oral healthcare services.

Research shows that few OMT patients use the free oral healthcare offered to them, and when they do, they usually suffer acute pain and discomfort [Citation3,Citation7,Citation27]. Despite a general increase in quality of life after OMT enrolment [Citation28–30], people with SUD experience stigma because of their poor oral health [Citation12,Citation31] and generally report reduced oral health-related quality of life [Citation13,Citation32]. However, our findings revealed that oral health is important for participants with OMT. This corresponds with the findings from a Norwegian study that found that among 29 participants with SUD, 92% considered the offer of free oral healthcare to be of great value [Citation13]. The importance of maintaining free dental healthcare for people with SUD is also endorsed by DHWs; a Norwegian study among 141 dentists and dental hygienists found that 80% felt it was important to maintain the free-of-charge oral care principle for this patient group [Citation33].

Furthermore, OMT participants had a specific interest in having their teeth fixed, as their dental status affected their self-image as well as their mental and physical health. This agrees with a study that argues that people in substance use recovery must develop a new identity under which the reconstruction of the mouth and teeth can be central [Citation3,Citation4]. Enrolment in OMT is itself a facilitator [Citation21], as it can help establish an organised and stable life [Citation34–36], allowing OMT participants to be more available, have time to focus on themselves and their personal needs and make better use of different care services such as oral healthcare.

However, OMT patients’ desires related to oral health can be addressed more explicitly than currently both by oral healthcare services and by the OMT system. Although the Norwegian authorities have strengthened the cross-sectoral collaboration between public dental services and treatment institutions, this collaboration is unsatisfactory [Citation20,Citation33]. The current study highlighted untapped potential: if OMT therapists increased their focus by asking OMT patients directly about their oral health, informing them of their rights, and assisting them with practical arrangements such as booking appointments and helping with treatment, they may be able to increase OMT patients’ use of dental healthcare services. This observation was also emphasised in a qualitative Australian study in which participants reported that treatment institutions should provide oral health-promoting information. In addition, knowledge of the service criteria and costs as well as how participants should contact dental clinics/dentists are considered to be critical to patients’ engagement in oral healthcare [Citation21]. Moreover, a recent Norwegian study among DHWs [Citation33] emphasised that employees from rehabilitation institutions were readily available to assist patients in making their dental appointments. Further, these employees knew what was included/not included under the free dental care package and this facilitated the collaboration between dental clinics and rehabilitation institutions. In addition, a Norwegian study among patients with severe or long-term mental illness emphasised the importance of receiving help with practical matters such as support and reminders from professional contacts to enable access to dental healthcare [Citation37]. As in the current study, help from professional contacts was invaluable in helping patients attend dental treatment.

Research emphasises the lack of education and training in the education system for DHWs in the treatment of OMT patients [Citation17]. This is supported by a study among dental professionals in Norway in which 80% reported a need for more knowledge when treating people with SUD [Citation33]. In the present study, DHWs’ knowledge of OMT was mainly gained through experience. Having knowledge of addiction, having personal experiences, and being in contact with people with SUD can reduce the stigmatisation [Citation38] that affects the dentist-patient relationship (DPR). Patients’ trust in the dentist, satisfaction with care, dental anxiety, participation in decision making, and therapeutic communication are important constructs of the DPR [Citation39,Citation40]. In relation to the DPR, the experienced DHWs interviewed in the current study stressed the importance of having empathy with OMT patients’ situations, meeting them in a respectful manner, and using different approaches depending on their needs. The DPR is the most significant component of satisfaction with dental care, followed by an organised service system and the scientific knowledge of dental personnel [Citation41]. This is also in line with a study of 51 patients with severe or long-term mental illness reporting that factors related to the dentist as an individual and the DPR were crucial facilitators influencing patients’ use of oral healthcare services [Citation37].

When enrolling in OMT, patients should receive information on their right to free-of-charge dental healthcare services. The participants in the current study had various recollections of whether such information was provided, highlighting at least two issues. First, if no information about their right to free oral healthcare is provided, this is a system failure and should be rectified. If no information is given because of OMT employees’ lack of knowledge about patients’ right to oral healthcare, this can easily be obtained by, for instance, establishing a closer collaboration between the OMT system and oral healthcare service. Second, if the information is provided to OMT patients but not remembered/recognised by them, the employees providing OMT, which meet them on a daily or weekly basis, ought to repeat this information.

Cognitive impairment including a disrupted perception of time [Citation42], decision making, and working memory [Citation43] is common among patients with SUD, and cognitive issues can make it difficult to remember and comply with dental appointments. To address this issue and avoid treatment dropouts, some oral health clinics have implemented SMS notifications to patients. As OMT patients often change their phone numbers, mobile phones are an unstable communication tool for this group of patients. However, both the DHWs and the OMT patients in the current study stated that notification was a useful tool for raising attendance. In addition, accompanying patients to oral treatment was seen as a facilitator, increasing both attendance and treatment quality [Citation33].

Study limitations

The OMT model in Norway varies. While it is generally integrated into tertiary healthcare services as outpatient treatment, medications are also provided through pharmacies and home nursing [Citation44]. In addition, the extent to which OMT patients receive free oral treatment under the Norwegian Act on oral healthcare services varies. These variations may question the applicability of our results in national and international settings. Despite these variations, our findings are of interest because of the insights they provide in a field in which research is lacking, namely, that the facilitators important for OMT participants’ use of oral healthcare services can be universal.

There may have been selection bias in our study. By choosing participants from oral healthcare clinics with the greatest number of OMT patients and volunteer OMT patients from outpatient units and low-threshold centres, there is a danger of including participants with strong opinions about oral healthcare services. However, adopting a qualitative approach allowed us to emphasise participants’ experiences, and our analysis showed that we gained a range of experiences of facilitators related to oral health from DHWs and OMT patients.

Qualitative studies are always influenced by researchers, and by using member checking [Citation25] where participants can provide their feedback on the analysis and results, one can ensure the ‘fit’ between the researchers’ interpretations of the participants’ experiences and their understanding of their own experiences. Instead of using member checking, owing to the short time for conducting this study, we discussed the codes/themes and analysis process with experienced researchers to ensure the credibility and quality of the analysis.

Conclusion

Although relatively few of our OMT participants use the free Norwegian oral healthcare service for OMT, several factors could raise uptake. More OMT patients may benefit from oral healthcare services by increasing the practical assistance and support provided to them. Another key finding could be to improve the DPR as well as DHWs’ communication skills and knowledge of OMT patients’ needs; similarly, the knowledge among health personnel working with OMT patients about their rights to oral healthcare should be disseminated. Therefore, existing facilitators could be used to a greater extent to increase communication between the oral healthcare system and the OMT system.

Author contributions

LTF, ANÅ, KI and SELC designed the study. KI and SELC conducted the focus groups interviews, individual interviews, transcribed the interviews and analysed the data. SELC wrote the article, and LTF, ANÅ, and KI contributed to writing and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the contributions of the OMT patients and oral health workers in Bergen. We also thank Vibeke Bråthen Buljovcic, Ole Jørgen Lygren, Maria Olsvold, Jan Tore Daltveit, Per Gundersen, and Mette Hegland Nordbotn for helping with the data collection.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Degenhardt L, Grebely J, Stone J, et al. Global patterns of opioid use and dependence: harms to populations, interventions, and future action. Lancet. 2019;394(10208):1560–1579.

- Baghaie H, Kisely S, Forbes M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between poor oral health and substance abuse. Addiction. 2017;112(5):765–779.

- Robinson PG, Acquah S, Gibson B. Drug users: oral health-related attitudes and behaviours. Br Dent J. 2005;198(4):219–224.

- Helvig JI, Jensdottir T, Storesund T. Har gratis tannhelsetilbud til rusmiddelavhengige ført til forventet effekt? (has free dental health services for people with substance use disorders led to the expected effect?). Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. 2017;122:774–780.

- Bowes C, Page G, Wassall R, et al. The need for further oral health research surrounding the provision of dental treatment for people with drug dependency. Br Dent J. 2019;227(1):58–60.

- Shekarchizadeh H, Khami MR, Mohebbi SZ, et al. Oral health behavior of drug addicts in withdrawal treatment. BMC Oral Health. 2013;13(1):11.

- Vanberg K, Husby I, Stykket L, et al. Tannhelse blant et utvalg injiserende heroinmisbrukere I Oslo (dental health among a selection of injecting heroin addicts in Oslo). Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. 2016;126:528–534.

- Gotfredsen K, Walls AW. What dentition assures oral function? Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007;18(Suppl 3):34–45.

- Watanabe Y, Okada K, Kondo M, et al. Oral health for achieving longevity. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(6):526–538.

- Fan J, Hser Y-I, Herbeck D. Tooth retention, tooth loss and use of dental care among long-term narcotics abusers. Subst Abus. 2006;27(1–2):25–32.

- Åstrøm AN, Virtanen J, Özkaya F, et al. Oral health related quality of life and reasons for non-dental attendance among patients with substance use disorders in withdrawal rehabilitation. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2021;1–8.DOI:10.1002/cre2.476

- Åstrøm AN, Özkaya F, Virtanen J, et al. Dental health care workers’ attitude towards patients with substance use disorders in medically assisted rehabilitation (MAR). Acta Odontol Scand. 2021;79.(1):31–36.

- Karlsen LS, Wang NJ, Jansson H, et al. Tannhelse og oral helserelatert livskvalitet hos et utvalg rusmiddelmisbrukere i norge (dental health and oral health-related quality of life in a selection of people with substance use disorders in Norway). Nor Tannlegeforen Tid. 2017;127:316–321.

- Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Lov om tannhelsetjenesten (tannhelsetjenesteloven) (Act on the Dental Health Service). 2020.

- Lobmaier P, Skeie I, Lillevold PH, et al. Statusrapport 2020. LAR behandling under første året med Covid-19 pandemi. (Status report 2020. OMT during the first year with Covid-19 pandemic). Oslo: Senter for rus- og avhengighetsforskning (SERAF) og Nasjonal kompetansetjeneste for tverrfaglig spesialisert rusbehandling (TSB); 2021.

- helsenorge.no. Who pays your dental bill? https://helsenorge.no/foreigners-in-norway/who-pays-your-dental-bill?redirect=false; 2020., accessed 07.01.21.

- Carlsen S-EL, Isaksen K, Fadnes LT, et al. Non-financial barriers in oral health care: a qualitative study of patients receiving opioid maintenance treatment and professionals' experiences. J Subst Abus Treat. 2021;16:44.

- Vikum E, Krokstad S, Holst D, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in dental services utilisation in a Norwegian county: the third Nord-Trondelag Health Survey. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(7):648–655.

- Charnock S, Owen S, Brookes V, et al. A community based programme to improve access to dental services for drug users. Br Dent J. 2004;196(7):385–388.

- Rossow I. Illicit drug use and oral health. Addiction. 2021;116(11):3235–3238.

- Cheah ALS, Pandey R, Daglish M, et al. A qualitative study of patients' knowledge and views of about oral health and acceptability of related intervention in an Australian inpatient alcohol and drug treatment facility. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(3):1209–1217.

- Mbumba A, Larsen MS. Oral helse og tannhelsevaner hos opioidavhengige som får legemiddeelassistert rehabilitering (LAR) I Bergen. (oral health and oral health-related behaviors for those recieving medically assisted rehabilitation (MAR) for opioid addiction.). Norway: Insitute for Clinical Odontology University of Bergen; 2018.

- Sivakanesan M. Dental health care workers' experience with and attitudes towards treatment of patients in medically assisted rehabilitation (MAR). Cross-sectional study in the public dental health care services on Hordaland and Roglanad counties. Norway: Faculty of Medicine, Department of Clinical Dentistry, University of Bergen; 2018.

- Lobmaier P, Skeie I, Lillevold PH, et al. Statusrapport 2019. Nye medisiner – nye muligheter? (status report 2019. New medicines - new opportunities?). Oslo: SERAF; 2020.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- QRS. Nvivo 12 Plus. In: Ltd P, editor.; 2018.

- Scheutz F. Dental habits, knowledge, and attitudes of young drug addicts. Scand J Soc Med. 1985;13(1):35–40.

- Carlsen S-EL, Lunde L-H, Torsheim T. Predictors of quality of life of patients in opioid maintenance treatment in the first year in treatment. Cogent Psychol. 2019;6:1565624.

- Karow A, Verthein U, Pukrop R, et al. Quality of life profiles and changes in the course of maintenance treatment among 1,015 patients with severe opioid dependence. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(6):705–715.

- Aas CF, Vold JH, Skurtveit S, et al. Health-related quality of life of long-term patients receiving opioid agonist therapy: a nested prospective cohort study in Norway. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2020;15(1):68.

- Brondani MA, Alan R, Donnelly L. Stigma of addiction and mental illness in healthcare: the case of patients’ experiences in dental settings. PLOS One. 2017;12(5):e0177388.

- Sharma A, Singh S, Mathur A, et al. Route of drug abuse and its impact on oral health-related quality of life among drug addicts. Addict Health. 2018;10(3):148–155.

- Hovden ES, Ansteinsson VE, Klepaker IV, et al. Dental care for drug users in Norway: dental professionals’ attitudes to treatment and experiences with interprofessional collaboration. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1):1–8. 229:

- Soyka M, Strehle J, Rehm J, et al. Six-Year outcome of opioid maintenance treatment in Heroin-Dependent patients: results from a naturalistic study in a nationally representative sample. Eur Addict Res. 2017;23(2):97–105.

- Dole VP. What have we learned from three decades of methadone maintenance treatment? Drug Alcohol Rev. 1994;13(1):3–4.

- Weinstein SP, Gottheil E, Sterling RC, et al. Long-term methadone maintenance treatment: some clinical examples. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1993;10(3):277–281.

- Bjørkvik JH, Quintero DP, Vika ME, et al. Barriers and facilitators for dental care among patients with severe or long-term mental illness. Scand J Caring Sci. 2021;1–9.

- Sattler S, Escande A, Racine E, et al. Public stigma toward people with drug addiction: a factorial survey. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78(3):415–425.

- Song Y, Luzzi L, Chrisopoulos S, et al. Are trust and satisfaction similar in dental care settings? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2020;48(6):480–486.

- Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff. 2010;29(7):1310–1318.

- Gürdal P, Çankaya H, Önem E, et al. Factors of patient satisfaction/dissatisfaction in a dental faculty outpatient clinic in Turkey. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28(6):461–469.

- Shahabifar A, Movahedinia A. Comparing time perception among morphine-derived drugs addicts and controls. Addict Health. 2016;8(1):32–40.

- Ramey T, Regier PS. Cognitive impairment in substance use disorders. CNS Spectr. 2019;24(1):102–113.

- Waal H, Bussesund K, Clausen T, et al. Statusrapport 2018. LAR i rusreformens tid (status report 2018. OMT in the time of drug reform). Oslo: Senter for rus- og avhengighetsforskning (SERAF) og Nasjonal kompetansetjeneste for tverrfaglig spesialisert rusbehandling (TSB); 2019.