Abstract

Objectives

To investigate systemic antibiotics utilization in emergency dental care and to determine the most common treatment measures performed during emergency visits in public versus private emergency care in Sweden.

Material and methods

Two questionnaires were answered by dentists at one large public and one large private emergency dental clinic in Stockholm, Sweden. The first questionnaire pertained to the emergency care provided to patients (n = 1023) and the second concerned the dentists’ (n = 13) own knowledge and attitudes towards antibiotic treatment and oral infections. The results of the questionnaires were tested using a Chi-square test.

Results

Sixteen percent of all patients seeking emergency dental treatment received antibiotics. The most common overall reason for visiting an emergency clinic was pain (52%, n = 519). The most common diagnoses made by the participating dentists in the public clinic were tooth/filling fracture (17%, n = 91) and gingivitis (14%, n = 76), while in the private clinic they were tooth fracture (29%, n = 146) and symptomatic apical periodontitis (15%, n = 72). Although the number of patients with infection was higher in the public care clinic, there was no significant difference in total number of antibiotic prescriptions between the two clinics. The rate of patients receiving antibiotic prescription as sole treatment was 41% (n = 34) in private care and 31% (n = 18) in public care. Thirty-one percent (n = 4) of dentists prescribed antibiotics for patients with diagnoses normally not requiring antibiotics, citing reasons such as time limitation, patient request, patient travel, patient safety, and follow-up not possible.

Conclusion

Although antibiotic prescription frequency among the Swedish emergency care dentists participating in this study was low, areas for improvement could include providing education to improve dentists’ knowledge on both antibiotic prescription in emergency dental care and treatment of acute oral infections.

Introduction

Rational antibiotic use is an important measure to help prevent the development of antibiotic resistance. Dentistry is a substantial contributor to the total antibiotic consumption in primary health care [Citation1], and guidelines and education focussing on avoiding unnecessary or incorrect antibiotic use have already been provided in many parts of the world. Efficient tutoring on antibiotic stewardship requires knowledge of prescribing attitudes and behaviour among dentists. Despite this, little is known about their prescription patterns. One area requiring improvement in antibiotic utilization is emergency dental care. Emergency dental visits are often unplanned and performed under time constraints and/or stressful conditions. As some acute interventions, such as root canal treatment or tooth extractions, can be time-consuming, it is tempting to combine or replace the procedure with antibiotic prescription. However, data regarding antibiotic prescription behaviour in emergency dental care are lacking.

Oral infection and/or inflammation (i.e. periapical periodontitis, pulpitis, abscesses and pericoronitis) are the most common reasons for patients seeking emergency dental care [Citation2]. In 2015, 28 EU countries reported that oral diseases and infections were among the costliest diseases [Citation3]. Oral infections may in many cases require immediate treatment to prevent local tissue damage and dissemination beyond the oral cavity. An untreated oral infection has the potential to cause life threatening complications by spreading via the adjacent fascial planes to the oral cavity and thereby causing damage to vital structures such as obstructing airways. It can therefore be assumed that antibiotic treatment is more common in emergency clinics. Although prescription of antibiotics should never replace proper diagnosis and appropriate treatment, supplementary treatment with systemic antibiotics may be necessary in the presence of constitutional symptoms and/or signs of a spreading infection. The majority of odontogenic infections can be treated without antibiotics if dentists are careful to eliminate the cause of the infection, extirpate pulp, drain abscesses and extract teeth as needed [Citation4,Citation5]. Traditionally it has been recommended that dentists avoid making incisions or performing extractions in inflamed/infected tissues. However, evidence from recent literature shows that there are no contraindications for oral surgical procedures aiming to drain infections, such as tooth extractions. On the contrary, an incision in the affected area reduces tissue pressure, and in combination with the appropriate dental treatment, can eliminate the cause of infection. These measures, if taken, can lower the risk of infection spreading [Citation6,Citation7].

The potential benefit of antibiotics is still widely debated in various fields of medicine, as well as in odontology. It has been estimated that the contribution of dental practices to the total amount of outpatient antibiotic prescription ranges from 7% to 11% worldwide [Citation1]. In Sweden, this contribution is estimated at 6% [Citation8]. Furthermore, in a survey of over 6000 general dental practitioners in the UK in 2008, 40% of dentists prescribed antibiotics on at least three occasions every week, and 15% of dentists prescribed daily [Citation9].

This study aims to investigate the use of antibiotics in emergency dental care, and to assess the most common reason for prescription in conjunction with performed emergency treatment. It also aims to investigate attitudes and routines towards antibiotic prescription.

Materials and methods

Study design

In this cross-sectional study, questionnaire data were collected from consecutive emergency visits at one public and one private dental clinic in Stockholm, Sweden. Data were collected from April 2016 to October 2016. Both clinics were profiled towards emergency dental care and constitute the two major providers of emergency dental care in the Stockholm area. All dentists working at the clinics for the entire duration of the data collection were asked to fill in the questionnaire. Dentists who either left one of the clinics before the end of the study or joined during the study duration were not included in the study. All dentists from both clinics filled in a self-administered questionnaire about patient treatment following each treatment session, and one questionnaire regarding their own personal attitudes and knowledge regarding antibiotic treatment.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was not required as the data collection does not include information from patient records.

Data collection

Two dental emergency clinics, one public (Centre I) and one private (Centre П), were included in the study. The clinics are geographically in close vicinity in Stockholm City, Sweden. Both centres had a well-established primary emergency clinic and a high number of emergency patients per day in an average of six patients per day.

The two clinics were the only major clinics open every weekday with extended opening hours for emergency dental treatment in the city of Stockholm during the study period. In the Stockholm area, all patients are referred to these clinics if their regular dentist/clinic is closed. These clinics and patients may thus be regarded as representative of a city population.

The directors of both clinics were initially contacted and agreed to participate. All dentists working at the clinics were contacted by the directors and asked if they would like to volunteer to participate. Verbal and written information was provided to the clinic directors and dentists prior to start of data collection. A pilot study of the questionnaires was performed in the dental emergency clinic at the Department of Dental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden to increase face validity of the questionnaire and content validity of the study. The results of the pilot study are not included here.

Questionnaires

The treating dentist received two separate questionnaires. The first was to be completed after every consecutively treated patient in the emergency clinic. This included information about the reason for the emergency clinic visit, diagnosis, and treatment, but no personal data that could reveal the patient’s identity. Other information included whether antibiotics were prescribed, and if so, whether it was for antibiotic prophylaxis or antibiotic treatment. If antibiotics were prescribed, the treating dentist was asked to clarify whether pain, swelling, proliferation, signs of infection dissemination beyond the oral cavity, affected general condition or another cause warranted the prescription. Further, the treating dentists were asked to state which antibiotic, dosage and duration were prescribed. Finally, questions were asked regarding the prescription of analgesic at the dental emergency clinic and if relevant, type and duration.

The second questionnaire was completed once for each participating dentist, and contained general questions regarding the dentist’s age, gender, number of years in practice, postgraduate education, oral infection diagnostic experience and knowledge of the national recommendations for antibiotic treatment in dentistry [Citation10].

Statistics

A statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows release 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Frequencies were used to describe the data. Differences in antibiotic and analgesic prescriptions between the public and private emergency clinics were tested using a Chi-square test. Relationships between antibiotic use and age, gender, reason of visit and diagnosis were tested using linear regression analysis. A level of significance of p < .05 was used to reject the null hypothesis.

Results

Collection of patient treatment questionnaires

A total of 1060 questionnaires regarding the emergency treatment provided were collected, 530 from each clinic. However, due to incomplete information, some questionnaires were excluded (3%, n = 37). Therefore, a total of 1023 questionnaires were included in the data analysis (527 questionnaires from the public clinic and 496 from the private clinic). Demographic data are presented in .

Table 1. Demographic data for patients receiving treatment at private or public emergency dental clinics in Stockholm, Sweden.

A total of 406 (40%) registered visits were considered to be non-genuine emergencies by the treating dentists, such as lost crowns/bridges, caries and/or gingivitis.

Reasons for attendance and diagnoses

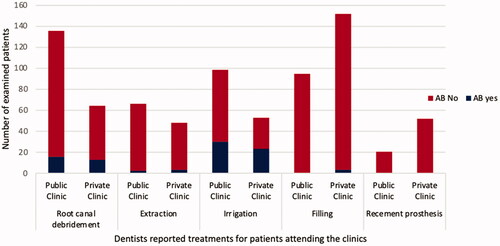

The most frequent reason for presenting at the emergency clinics was pain. In the public clinic, 60% of visits (n = 311) were due to pain, while 43% of private clinic visits (n = 208) were also a result of tooth pain ( and ).

Figure 1. Antibiotic prescription according to symptoms in both emergency clinics. *p-value of < .05 was considered statistically significant. AB yes = treatment provided with antibiotic prescription; AB no = treatment provided with no antibiotic prescription; Fracture = tooth fracture.

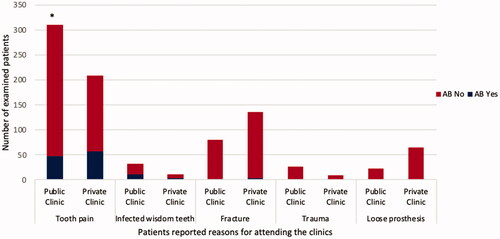

In the public clinic, the most common diagnoses made by the participating dentists were tooth/filling fracture (17%, n = 91) and gingivitis (14%, n = 76), while in the private clinic the most common diagnoses were tooth fracture (29%, n = 146) and symptomatic apical periodontitis (SAP) (15%, n = 72) ().

Figure 2. Antibiotic prescription according to diagnosis in both emergency clinics in both emergency clinics. *p-value of < .05 was considered statistically significant. AB yes = treatment provided with antibiotic prescription; AB no = treatment provided with no antibiotic prescription; Fracture = tooth/filling fracture.

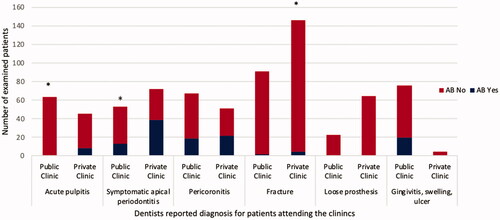

Treatment provided

The most frequent emergency treatment was found to differ between the clinics. In the public clinic, more than a quarter of the visits resulted in root canal debridement (26%, n = 135), while in the private clinic, the most common treatment was fillings (31%, n = 151) (). In addition, in 15% (n = 77) and 17% (n = 83) of the public and private clinic visits, respectively, no local dental treatment was performed.

Prescribing of analgesics and antibiotics

Painkillers were prescribed for 10% of the visits during the six-month study period. There was a significant difference between the two clinics in the number of analgesics prescribed (p = .001). Analgesics were prescribed in only 12% (62/527) of public clinic visits and 7% (36/496) of private clinic visits. All other patients (88% [465/527] of public clinic and 93% [460/49] of private clinic visits) did not receive any pain medication. Analgesics were either paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which were prescribed for complaints of pain, infected wisdom teeth and swelling, infection, and tooth fractures.

Frequency of antibiotic prescription did not significantly differ between the two clinics. In both clinics, antibiotics were prescribed for 16% of cases (15% [80/527] in the public clinic and 17% [83/496] in the private clinic) despite a significant difference in number of individuals seeking with symptoms related to infection. The rate of patients receiving antibiotic prescription as sole treatment was 41% (n = 34/83) in private care and 23% (n = 18/80) in public care.

Penicillin V was the most frequent antibiotic prescribed (88%, n = 142). Other antibiotics prescribed were clindamycin (6%, n = 10), metronidazole (2%, n = 3), amoxicillin (1%, n = 2), and a combination of penicillin V and metronidazole (3%, n = 5). Antibiotic treatment duration varied between 3 and 10 days, but the most prescribed treatment course was for 7 days (45%, n = 37).

The most common diagnoses that led to the prescription of antibiotics were symptomatic apical periodontitis (32%, n = 52), pericoronitis (26%, n = 41), and gingivitis (13%, n = 20) (). Thirty-two percent of patients (n = 52) (18 patients (23%) from the public clinic and 34 patients (41%) from the private clinic) received an antibiotic prescription with no local treatment.

There was a significant relationship between antibiotic prescription and reasons for visit such as tooth pain (p = .001), filling fracture, or prosthesis fracture (p = .001), trauma (p = .031), loose prosthesis (p = .001), swelling (p = .001), infection (p = .043) and cont. root canal treatment (p = .048). There was a significant relationship between prescription of antibiotics and diagnosis of acute pulpitis (p = .001), symptomatic apical periodontitis (p = .001), gingivitis (p = .001), tooth/filling fracture, abscess (p = .001), caries (p = .001), prosthesis repair (p = .001) and pericoronitis (p = .001) (). Regression analysis showed a non-significant relationship between antibiotic prescription and gender, age, reason for visit, diagnosis, and treatment.

Table 2. Prevalence of antibiotic usage for sex, age, reason for visit and diagnosis at public and private emergency dental centres in Stockholm, Sweden.

Dentist’s questionnaire

During the study period we collected 13 questionnaires from treating dentists at both clinics. Most dentists were female (69%, n = 9), with 31% male (n = 4). The dentists’ clinical experience varied from 4 to 40 years with a mean of 17 years. Most of the dentists (77%, n = 10) were working in emergency dental care, 15% (n = 2) were commonly working as general dentists, and 8% (n = 1) was a specialized dentist. The dentists were asked if the national recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis prescription prior to treatment were clear. Eighty-three percent of the dentists (n = 11) answered ‘yes’ and 16% (n = 2) replied ‘no’. Moreover, when asked whether the national recommendations for antibiotic treatment of odontogenic infections, 31% of dentists (n = 4) prescribed antibiotics for patients normally not requiring antibiotics (such as patient travel, patient safety, follow-up not possible). One-third of the dentists (n = 4) admitted that they occasionally prescribed antibiotics due to time limitation or patient request ().

Table 3. Answers to questions about their own antibiotic prescribing behaviours by dentists working in public and private emergency dental clinics in Sweden.

Discussion

The results of this study show that a relatively small fraction of emergency dental treatments required antibiotic prescription, taking into the consideration that this study took place in Stockholm which means this survey avoided the remote area that could have changed results and outcome. However, many of the prescriptions were incorrect as they were not related to the presence of infection. Although there was no significant difference between the two clinics in terms of the proportion of use of adjunctive systemic antibiotics, the number of visits in the private clinic due to an odontogenic infection (SAP or pericoronitis) was higher.

Despite the greater number of diagnosed infections seen in the public clinic, the lack of a difference in number of antibiotic prescriptions between the two clinics could be due to how work and employment are organised in these different types of dental clinics in terms of implementation of national recommendations [Citation11]. Moreover, other factors that may influence antibiotic prescribing patterns among dentists such as postgraduate education, diagnostic skills/clinical experience and knowledge of national recommendations may have differed between the dentists in the two clinics [Citation12]. A limitation of the current study is that the local efforts, in private as well as public clinics, to work in alignment with national recommendations of antibiotic use have not been investigated.

Recently, a report from the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare showed that the strong reduction in antibiotic prescription seen in Swedish dentistry mainly occurred in public dental care [Citation13], while the private clinics showed a more modest reduction in the use of antibiotics. The present study, including only emergency dental visits in two clinics in the Stockholm region, could not show any difference in antibiotic prescription between the participating clinics. This could indicate that the difference between public and private dental care may not lie within the spectra emergency treatments.

Penicillin V (PcV) was the most often prescribed antibiotic compound. This is in adherence with the Swedish national recommendation which favours prescription of PcV for five to seven days duration [Citation14]. However, several European studies have shown that amoxicillin is the first-choice antibiotic compound among general dental practitioners, endodontists, and dental surgeons [Citation12,Citation15–20]. In the present study, the results showed that most dentists in both participating emergency clinics prescribed antibiotics for five to seven days, as recommended. The prescribed duration of antibiotics varied most in the private dental emergency clinic, ranging from 3 to 10 days. This may indicate an effort to individualize antibiotic treatment.

In most cases, no analgesics were prescribed. The explanation for this can be due to the vast variety of reasons for the emergency visits. Dentist tendency to recommend non-prescription analgesics as first choice could also be part of the explanation. Also, the emergency treatment given can have resulted in sufficient pain reduction.

The results of the present study show that the most common reason for attending emergency clinics was tooth pain caused by either a tooth fracture or an odontogenic infection (SAP, acute pulpitis, or pericoronitis). Odontogenic infections were more commonly treated in the public clinic than the private clinic. However, the private clinic had a significantly higher number of tooth/filling fractures than the public clinic. A possible explanation is that patients with odontogenic infections who attended the public emergency clinic may not be regular dental attenders and only seek care if they have an oral emergency.

The proportion of patients receiving adjunctive systemic antibiotics was, in some cases, in agreement with previous studies. According to the results of the present study, 32% of the emergency dental visits resulting in antibiotic prescription did not involve any local dental treatment. In Spain, 52% of dentists prescribed antibiotics without any local treatment [Citation17], and 59% of dentists in both Saudi Arabia [Citation21] and India [Citation22] prescribed antibiotics for patients diagnosed with SAP. In the present study, most of the patients diagnosed with dental abscesses were seen at the public clinic. Comparison can be made with a study from Belgium, where dentists prescribed antibiotics in 46% of periodontal abscess cases and 59% of periapical abscess cases – in both conditions no local treatment was provided [Citation18]. Although our results showed relatively lower rates of antibiotic prescription than in the Belgium study [Citation18], they indicate the importance of performing an incision in the dental abscess. It is important that dentists be cautious about the development of cellulitis, as the transudate and exudate can spread through interstitial and tissue spaces [Citation23]. However, it is incorrect to treat pulpitis with antibiotics as it is an inflammatory condition that could easily be alleviated with trepanation to the pulp chamber. There were only nine cases (8%) in the present study where antibiotics were prescribed for pulpitis. This is similar to previous findings from Turkey [Citation19], but lower than reported in a Belgium study where 32% of patients with pulpitis were treated with antibiotics [Citation18]. When treating odontogenic infections, the aim should always be to achieve drainage, and if possible, remove the cause of infection. Drainage can be executed through root canal treatment, incision of abscess, extraction of teeth or scaling and root planning in the gingival pocket of the affected teeth. In fact, draining abscesses improves prognosis, and in turn, reduces either the need for antibiotic treatment, or the duration of antibiotic treatment. More importantly, if the dentist succeeds with an effective drainage, then antibiotic treatment is usually not necessary.

The dentists’ questionnaire showed that antibiotics may be prescribed due to lack of time for adequate treatment, or if the patient asked for a prescription. Some dentists stated that they prescribe antibiotics for safety reasons such as if the patient denied follow-up visits or planned to travel. This should be interpreted with great caution due to the limited number of participation dentists (n = 13). It was also shown in a study from 2004 that dentists prescribed antibiotics to approximate 6% of patients due to patient expectation [Citation24]. A recently published study has confirmed the same justification for the prescription of antibiotics with addition to the lack of dental higher qualification [Citation25]. However, dentists prescribing antibiotics should not be influenced by patient demand in ‘just in case’ situations or the fact that it is the last day before the weekend or holiday [Citation17]. Inappropriate prescription of antibiotics includes inaccurate diagnosis, incorrect dosage, and incorrect treatment duration or choice of antibiotic preparations [Citation17]. This highlights the difficulties a dentist may encounter when aiming to restrict antibiotic usage.

A limitation of this study is that the questionnaires have not been validated. Also, the study was designed to investigate reported treatment behaviour rather than registered patient data, limiting data analysis. Thus, it is not known if the patients included this study are representative of dental patients in Sweden. Although no information regarding more severe symptoms such as fever were included, it was reported that antibiotic prescription was highest when the dentist evaluated that there was a sense of malaise, swelling, suspicion of infection or pericoronitis. The presence of fever is important for the consideration of antibiotic prescription and should be included in further studies.

It is difficult to justify the prescription of antibiotics among the participating dentists in the present study or identify the underlying reason of not providing a local treatment for various odontogenic infections. The results presented in the present study do provide some interesting information around dentists’ prescribing patterns, but future studies in this field should incorporate access to patient records when needed.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that there is room for improvement concerning the prescription of antibiotics among the participating dentists in public and private emergency dental clinics. More dentists need to be aware of the benefit of local treatment (i.e. drainage) for diagnoses such as SAP and dental abscesses in addition to prescribing antibiotics and/-or analgesics. Moreover, there is a need for improving knowledge regarding antibiotic prescription in emergency dental treatment.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: Dalia Khalil, Bodil Lund, Margareta Hultin, Gabriel Baranto

Methodology: Dalia Khalil, Gabriel Baranto, Margareta Hultin

Formal analysis: Dalia Khalil

Investigation: Dalia Khali, Gabriel Baranto

Data Curation: Dalia Khalil

Writing – original draft preparation: Dalia Khalil, Margareta Hultin, Bodil Lund

Writing – review and editing: Dalia Khalil, Margareta Hultin, Bodil Lund

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Johnson TM, Hawkes J. Awareness of antibiotic prescribing and resistance in primary dental care. Prim Dent J. 2014;3(4):44–47.

- Dalén T. Indikationer för antibiotikaprofylax i tandvården hos ledprotesopererade patienter. (Publication in Swedish). Läkemedelsverket. 2012;56:22–35.

- Righolt AJ, Sidorenkov G, Faggion CM Jr, et al. Quality measures for dental care: a systematic review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2019;47(1):12–23.

- Al-Haroni M, Skaug N. Knowledge of prescribing antimicrobials among Yemeni general dentists. Acta Odontol Scand. 2006;64(5):274–280.

- Smith A, Al-Mahdi R, Malcolm W, et al. Comparison of antimicrobial prescribing for dental and oral infections in England and Scotland with Norway and Sweden and their relative contribution to national consumption 2010-2016. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1):172.

- Adielsson A, Nethander G, Stalfors J, et al. Infektioner i halsens djupare spatier är inte sällan odontogena. (Publication in Swedish). Tandläkartidningen. 2000;3:32–40.

- Pesis M, Bar-Droma E, Ilgiyaev A, et al. Deep neck infections are life threatening infections of dental origin: a presentation and management of selected cases. Isr Med Assoc J. 2019;21(12):806–811.

- Swedres-Svarm 2018. Consumption of antibiotics and occurrence of resistance in Sweden. Solna/Uppsala ISSN1650-6332. (Publication in Swedish). Public Health Agency of Sweden and National Veterinary Institute.www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/publicerat-material/ or www.sva.se/swedres-svarm/.

- Lewis MA. Why we must reduce dental prescription of antibiotics: European Union antibiotic awareness day. Br Dent J. 2008;205(10):537–538.

- Skogh Andrén A, Aronsson B, Aust-Kettis A, et al. Rekommendationer för antibiotikabehandling i tandvården. (Publication in Swedish). Läkemedelsverket. 2014;25:19–30.

- Lund B, Cederlund A, Hultin M, et al. Effect of governmental strategies on antibiotic prescription in dentistry. Acta Odontol Scand. 2020;78(7):529–534.

- Dailey Y, Martin M. Therapeutics: are antibiotics being used appropriately for emergency dental treatment? Br Dent J. 2001;191(7):391–393.

- Socialstyrelsen. Antibiotikaförskrivning inom tandvården. Statistikrapport baserad på uppgifter från läkemedels- och tandhälsoregistret 2009–2017. (Publication in Swedish). Socialstyrelsen. 2019. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/statistik/2019-4-14.pdf.

- Palmer N, Ireland R, Palmer S. Antibiotic prescribing patterns of a group of general dental practitioners: results of a pilot study. Prim Dent Care. 1998;5(4):137–141.

- Tulip D, Palmer N. A retrospective investigation of the clinical management of patients attending an out of hours dental clinic in Merseyside under the new NHS dental contract. Br Dent J. 2008;205(12):659–664.

- Segura‐Egea J, Velasco-Ortega E, Torres-Lagares D, et al. Pattern of antibiotic prescription in the management of endodontic infections amongst Spanish oral surgeons. Int Endod J. 2010;43(4):342–350.

- Rodriguez-Núñez A, Cisneros-Cabello R, Velasco-Ortega V, et al. Antibiotic use by members of the Spanish endodontic society. J Endod. 2009;35(9):1198–1203.

- Mainjot A, D'Hoore W, Vanheusden A, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in dental practice in Belgium. Int Endod J. 2009;42(12):1112–1117.

- Kaptan RF, Haznedaroglu F, Basturk FB, et al. Treatment approaches and antibiotic use for emergency dental treatment in Turkey. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2013;9:443–449.

- Perić M, Perković I, Romić M, et al. The pattern of antibiotic prescribing by dental practitioners in Zagreb, Croatia. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2015;23(2):107–113.

- Iqbal A. The attitudes of dentists towards the prescription of antibiotics during endodontic treatment in North of Saudi Arabia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(5):ZC82–ZC84.

- Garg AK, Agrawal N, Tewari RK, et al. Antibiotic prescription pattern among Indian oral healthcare providers: a cross-sectional survey. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(2):526–528.

- Slots J, Pallasch TJ. Dentists' role in halting antimicrobial resistance. J Dent Res. 1996;75(6):1338–1341.

- Palmer NO, Batchelor PA. An audit of antibiotic prescribing by vocational dental practitioners. Prim Dent Care. 2004;11(3):77–80.

- Kerr I, Reed D, Brennan AM, et al. An investigation into possible factors that may impact on the potential for inappropriate prescriptions of antibiotics: a survey of general dental practitioners' approach to treating adults with acute dental pain. Br Dent J. 2021;231:92.