Abstract

Objectives

To determine the prevalence and severity of dry mouth by age, gender, presence of disease, and medication intake for patients aged 18 years and over, seeking primary health care on the west coast of Sweden (Region of Västra Götaland, VGR).

Materials and methods

Cross-sectional study conducted among patients (n = 374, age ≥ 18) visiting primary health care providers (n = 4) in VGR for any medical reasons. Patients were invited to participate by answering a single-item question, ‘Have you experienced dry mouth in the last six months?’ Patients giving positive answers (n = 163) were asked to fill in the 11-item Xerostomia Inventory (XI) questionnaire to determine the variability and severity of xerostomia. Patients replying ‘No’ (n = 211) to the single-item question were considered not to have xerostomia and included in the non-xerostomia group.

Results

The overall prevalence of xerostomia was 43.6% with a female dominance (61.2%). The prevalence in different age groups among females and males was similar. The number of medications and/or diseases are positively associated with xerostomia. Medication was a significant predictor of the prevalence of xerostomia, regardless of age and gender (p < .001). Patients with five or more medications had the highest prevalence of xerostomia (71.2%).

Conclusion

Patients seeking primary care on the west coast of Sweden have a high prevalence of xerostomia. Factors associated with xerostomia were female gender and medications and/or diseases. Awareness is required to manage patients with xerostomia in medical and dental care.

Introduction

Xerostomia is the individual’s perceived symptom of dry mouth [Citation1]. Although, the condition may occur as a result of changes in the saliva composition or flow; the amount of saliva is not always reduced [Citation2].

Patients with xerostomia have problems with speech, deglutition, and mastication. Malodour, a burning sensation in the mouth, altered sense of taste, dental caries, oral mucosal changes, and fungal infections are also common in these patients [Citation3]. Xerostomia may also lead to limited social communication, with deteriorated quality of life as a result [Citation4]. The condition has mainly been associated with poor oral health-related quality of life in the older adult population [Citation5,Citation6]. Yet, young and middle-aged individuals may also suffer from dry mouth, due to side effects of medication [Citation4].

Dry mouth is the third most common side effect of drugs [Citation7]. More than 500 drugs and about 42 different drug groups may cause xerostomia [Citation7,Citation8]. Many of them cause xerostomia as a side effect, but very few have been tested for objective changes in the salivary flow rate [Citation7,Citation9]. The prevalence of xerostomia increases in patients with polypharmacy [Citation10]. Numerous conditions, including systemic/autoimmune (diabetes, thyroid diseases, Sjögren’s syndrome, sarcoidosis) and neurodegenerative (Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s) diseases may cause xerostomia, with or without decreased amounts of saliva [Citation11]. Other causes include nutrient deficiencies, viral infections, febrile conditions, dehydration, depression, anxiety, stress, and radiotherapy of the head and neck region [Citation11,Citation12]. Diseases, together with the patient’s overall health condition and medication, may contribute to a sensation of oral dryness, with or without a decreased amount of saliva [Citation2,Citation7].

Xerostomia is comprised of subjective symptoms, it can be assessed by a single-item question or by multi-item approaches, such as the Xerostomia Inventory (XI). Although the single-item question is a quick and simple method, it has limitations in assessing the variability of xerostomia. The Xerostomia Inventory (XI) comprises 11 questions aimed at capturing experiences of dry mouth-related problems. It is a validated instrument to measure the severity and variability of subjective dry mouth [Citation1].

Variations in the prevalence of xerostomia range from 0.9 to 64.8% [Citation13], attributed to differences in measurement methods and the populations studied, as well as the age of the study individuals [Citation10]. Moreover, the prevalence of xerostomia has been reported to be lower in men (10–26%) than in women (10–33%) [Citation14]. Previous studies have mainly paid attention to xerostomia prevalence among older adults [Citation13]. There are no epidemiological studies reporting the prevalence in the total adult population (aged ≥18) associated with the intake of medication or the presence of disease. Primary health care providers treat a mixed population of adult patients, where different types of medicines are prescribed for different diagnoses. Primary care, therefore, provides a unique possibility to investigate the prevalence of xerostomia. This study aimed to determine the prevalence and severity of xerostomia by gender, age, intake of medication, or presence of diseases in adult patients seeking four primary care providers on the west coast of Sweden (Region of Västra Götaland).

Materials and methods

Study population

This cross-sectional study was conducted at four primary care provider clinics that are representative of different socioeconomical areas in the Region of Västra Götaland. Patients aged 18 years and over visiting these primary care providers were invited to participate in the study and complete a questionnaire between September and November 2020. Of the 440 patients who were invited 40 patients declined to participate. Each primary care provider was asked to recruit 100 patients, and a total of 400 patients were enrolled in the study. However, 26 patients were excluded due to missing information. In total, 374 patients were included.

Patients visiting primary health care providers for any health reasons were invited consecutively to participate in the study by first answering a single-item question, ‘Have you experienced dry mouth in the last six months?’ Patients answering ‘No’ to the single-item question were considered not to have xerostomia and were included in the non-xerostomia group. Patients giving positive answers were asked to complete the 11-item Xerostomia Inventory (XI) questionnaire to determine the variability and severity of their xerostomia [Citation1]. The Swedish validated form of the Xerostomia Inventory (XI) questionnaire was used in the study to determine the severity of the xerostomia [Citation15]. The Xerostomia Inventory (XI) questionnaire consists of eleven questions with five response options yielding different scores (Never = 1, Rarely = 2, Sometimes = 3, Often = 4, and Always = 5). The total score is calculated from the patients’ responses, with the lowest possible score being 11 and the highest possible score is 55. High scores indicate a higher grade and more severe symptoms of xerostomia [Citation1]. The xerostomia group was divided into three groups: Mild xerostomia (12–22 points), moderate xerostomia (23–33 points), and severe xerostomia (34–49 points). The patients’ age, gender, presence, and number of diseases and medications, if any, were also gathered.

The Swedish Central Ethical Review Board approved the study (reg. no. 2020-03127) and it has been reported in accordance with the STROBE statement [Citation16]. All patients signed an informed consent form before the start of the study.

Data analysis

In a power calculation, 374 patients were needed in the study for a 95% confidence interval with a 5% margin of error. Continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Nominal and categorical data were presented as numbers and proportions, expressed as percentages (%). The analysis was performed with logistic regression, where xerostomia was set as a dependent variable. Simple logistic regression was carried out first, with each predictor variable described without any controlling factors. Separate models of logistic regression with forced entry methods were performed to assess the importance of each factor while controlling for all other factors in the model. The predictor variables in the first model were sex, age, any disease, or any medication. The predictor variables in the second model were sex, age, amount of medication, or number of diseases. p < .05 with a 95% confidence interval was considered significant. Spearman’s correlation was used to check for possible confounding effects between the predictor variables before entering them into the model.

Results

presents the demographic patient data (n = 374) according to gender, age, presence of xerostomia, diseases, and intake of medication. The majority of the participants were females. Male patients contributed 38.7% (n = 145) of the total number of participants, mean age of 60 ± 18.3. Almost two-thirds of the study participants replied ‘yes’ to the question ‘Do you have any diseases?’ Among them, more than one-third were females. Almost seven in ten were on medication, of them 71.2% (n = 152) were females and 27.5% (n = 103) were males.

Table 1. Demographic data of patients according to gender, age, presence of xerostomia, diseases and intake of medications.

The overall prevalence of xerostomia was 43.6% (n = 163). Patients on treatment with five or more medications, so-called polypharmacy, had a higher prevalence of xerostomia (71.2%) than the overall study population. Almost equal numbers of females (n = 37) and males (n = 29) were included in the polypharmacy group with the mean age being 71 and the mean total number of medications being 7.2. All patients in the polypharmacy group had xerostomia except eleven males and eight females who did not report xerostomia with a mean total number of medications being 6.8.

According to the Xerostomia Inventory (XI), the most frequently reported oral symptom in the xerostomia group was ‘dry mouth at night or waking up to drink water’ (85.9%, n = 140). In the xerostomia group, 55.8% (n = 91) of the patients had a dry feeling while eating and 51.5% (n = 84) of them needed to use lozenges or chewing gum to relieve dry mouth. Among the patients with xerostomia, 58.9% (n = 96) answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Do you need to drink water to swallow food’. The percentage of patients reporting difficulties while eating dry food in the xerostomia group was 62.0% (n = 101); however, among them, 25.8% (n = 42) experienced this only occasionally. Among all xerostomia patients, 89.2% experienced dry skin, 86% dry lips, 77% dry eyes, and 74% dryness of the nasal mucosa.

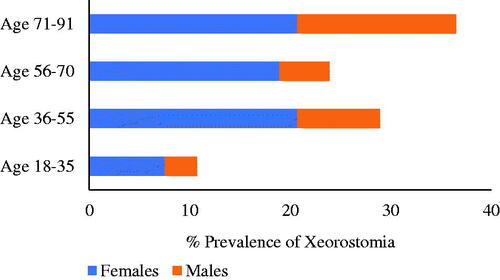

According to Xerostomia Inventory (XI) score, as shown in , most of the patients with xerostomia had moderate grade xerostomia (59.5%, n = 97), with a female predominance (72.2%, n = 70). Females were also predominant in the severe grade xerostomia group (88.5%, n = 23). However, the mild xerostomia group had an equal distribution between females and males.

Figure 1. The xerostomia severity grade was divided into three groups: Mild xerostomia (12–22 points), moderate xerostomia (23–33 points), and severe xerostomia (34–49 points). The sum total of points was calculated from the patients’ answers (n = 163) to the Xerostomia Inventory (XI) questionnaire.

Prevalence of xerostomia according to age and gender

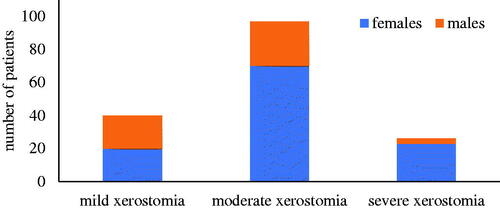

The four age groups in show that the prevalence of xerostomia differs with age and gender. Overall, females had a higher prevalence of xerostomia (67.8%, n = 108) than males (32.2%, n = 51). The odds of reporting xerostomia were 1.64 times greater for women than for men (p = .023, 95% CI 1.07–2.52). After adjusting for age and diseases, the odds ratio for women to report xerostomia compared to men was even more prominent (OR: 1.96; 95% CI 1.24–3.08; p = .004).

As seen in , the prevalence of xerostomia in different age groups of female patients was similar. Among the male patients, the highest prevalence of xerostomia was seen in the 71–91-year age group with 15.8% (n = 25).

Independent of gender, increasing patient age initially showed a significant association with xerostomia (p = .01, 95% CI 1.00–1.02). However, age was not significant when adjusting for disease or medication, indicating that xerostomia could be predicted by disease or medication and not by age per se. Spearman’s correlation between age and any disease was 0.366, p < .001. The mean age (59 years) in the xerostomia group (n = 159) was slightly higher than the mean age (53 years) in the non-xerostomia group (n = 215).

Medication and disease frequency

shows the total number of medications/diseases and the frequencies in the xerostomia and non-xerostomia groups. Medication and disease frequencies were calculated as the total number of medications/diseases per patient in the xerostomia and non-xerostomia groups, respectively. The mean age of the males in both the xerostomia (63 years) and the non-xerostomia group (59 years) was slightly higher than that of the females in the respective groups (59 and 53 years).

Table 2. Medication and disease frequency in the xerostomia and non-xerostomia groups.

The total number of medications (n = 474) used in the xerostomia group was higher than that (n = 384) in the non-xerostomia group. Medication frequency in the xerostomia group was higher (2.98) compared with the non-xerostomia group (1.78) (). Medication was a significant predictor of the prevalence of xerostomia in the study group (OR 2,4; 95% CI 1.50–3.83; p < .001). For every additional drug, the odds ratio increased by 1.18 (95% CI 1.09–1.28).

The medication frequency for females in the xerostomia group was higher than for females in the non-xerostomia group; 2.83 and 1.38, respectively. The medication frequency for males was higher than for females in both the xerostomia and the non-xerostomia group; 3.29 and 2.3, respectively ().

The xerostomia group had a higher disease frequency than the non-xerostomia group (). The odds to report xerostomia were 3.32 times greater in those reporting a disease compared with those who did not (95% CI 2.09–5.26). For every report of additional disease, the odds of having xerostomia increased by 1.67 (95%CI 1.36–2.06).

Females in the xerostomia group had a higher disease frequency (1.39) than females in the non-xerostomia group (0.63). A similar pattern was seen for males; a higher disease frequency was found in the xerostomia group (1.47) than in the non-xerostomia group (1.02) ().

Discussion

The result of the current study reveals that adult patients aged 18 and over seeking primary care providers for any medical reasons had a high prevalence (43.6%) of subjective dry mouth. As far as we know, this is the first cross-sectional study conducted in primary care to determine the prevalence of dry mouth in adult patients. The most noticeable result found in the present study was that females had a higher prevalence of xerostomia (61,2%) than males and showed a wide age span, between 36 and 91 years. However, men with xerostomia presented a narrower age span, with a prevalence of 35%.

The results of the present study from primary care showed that the female gender, regardless of age and medication, was a risk factor for higher prevalence. The prevalence of dry mouth in England has been shown to be higher for females among adults attending general dental practices [Citation17]. After menopause oestrogen deficiency has been considered a contributing factor in females for xerostomia [Citation18]. Moreover, Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disease of the exocrine glands that predominantly affects women and leads to reduced secretion of saliva and tear fluid. [Citation19]. Accordingly, it is likely that women are more prone to develop xerostomia. However, the factors contributing to xerostomia in females cannot be explained by the present study.

Population-based studies reporting on the prevalence of xerostomia are scarce. According to a systematic review, the prevalence in the community was ∼20% [Citation13]. The general prevalence of xerostomia in a population-based study in urban areas of Brazil was 11%, which was associated with oral health, general health, and psychosocial well-being. These factors were aggravated by ageing [Citation20]. In line with previous studies, the present study showed a higher prevalence of xerostomia with increasing age [Citation3,Citation10,Citation13,Citation20]. A previous study has reported poor oral health among young adults due to the use of the medication causing dry mouth [Citation4]. However, in the present study, the xerostomia prevalence in different age groups of females was similar. Xerostomia is the third most reported adverse effect of medication [Citation7]. The effect of medications on the salivary glands is complex. The secretory reflex pathway can be inhibited at several levels, including the central nervous system and the neuroglandular junction of the major and minor salivary glands [Citation21]. Accordingly, a wide range of drug groups interferes with the salivary secretory pathway, such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticholinergics, antihypertensives, diuretics, neuroleptics, analgesics, antihistamines, and sedatives [Citation7]. The present study noted if patients were on any medication, but not the type of medicine. As a result, medication was strongly associated with xerostomia and every additional medication increased the xerostomia outcome.

Polypharmacy, which was defined as being treated with five or more medications, is common among older adults and increases the xerostomia prevalence dramatically [Citation9,Citation10]. This agrees with the present study that the polypharmacy group had a higher prevalence (71.2%) with a majority of older adult patients. The patients in this group had mainly reported symptoms of moderate xerostomia without any gender difference. However, older adult patients with severe xerostomia symptoms, who already suffer from systemic diseases, may not complain as much as younger adults [Citation22].

A limitation of the study is that the salivary flow rate was not measured; therefore, the xerostomia grade cannot be correlated with the amount of saliva secreted. Subjective dry mouth -xerostomia can be seen with or without objective dry mouth-hyposalivation [Citation2]. Studies presenting results on both subjective and objective dry mouth in the same population show that they are in fact separate conditions. The prevalence of xerostomia and hyposalivation shows great variability. Thus, both conditions in the same individual appear to be very rare [Citation23].

Several methods have been used for the measurement of subjective symptoms of xerostomia. The Xerostomia Inventory (XI) is a multi-item approach providing a continuous score with respect to the severity and variability of the subjective symptoms of dry mouth [Citation1]. In the present study, xerostomia experienced in the last six months was determined first by the single-item question, followed by the Xerostomia Inventory (XI) to discriminate between individuals with different symptom grades at a specific point in time. According to Thomson, the Xerostomia Inventory (XI) is a validated method that helps clinicians and researchers by providing the underlying characteristics of dry mouth-related problems [Citation1]. In young adults aged between 26 and 32 years in New Zealand, the prevalence of xerostomia was 10% and two-thirds reported dry mouth ‘occasionally’. Treatment with antidepressants, iron supplements, and antihypertensive drugs already at a young age has been found to be a risk factor [Citation4]. In the present study, 50 and 25% of the xerostomia patients reported having a dry mouth feeling ‘sometimes’ and ‘often’, respectively. The most common oral symptom was dry mouth at night (86%) and 27% of the patients experienced it ‘often’. However, the study population in the present study had a higher mean age, 57 years, and high use of medication. Besides oral symptoms, the most common other problems among xerostomia patients were dry skin, dry lips, and dry eyes. Dryness of the skin and lips have been reported as common side effects of the systemic use of statins, antihypertensives, antihistamines, and retinoids [Citation24–26]. Retinoids used in the systemic treatment of acne are known to cause oral dryness and changes in the oral and lip mucosa [Citation26].

The coexistence of systemic diseases, such as hypertension, cardiovascular disorders, and diabetes mellitus, increases with age. Accordingly, the intake of medication increases with higher disease frequency, which in this study correlated well with the xerostomia prevalence. The association of xerostomia with medication and disease was presented separately. However, in line with other studies, it is more likely that side effects of the medication have a greater effect on the xerostomia outcome than diseases per se [Citation9,Citation26].

Knowledge gained from the study may raise awareness among healthcare providers of the high prevalence of xerostomia in primary care, especially among females and individuals with several diseases and/or medications. Since the number of medicines taken is an important factor, reducing the number of medicines should be attempted, if possible. Collaboration between dental and primary care professionals is fundamental in providing oral health care for patients with xerostomia. Early detection of dry mouth has a major effect on both oral health and quality of life. If it remains unnoticed and no preventive measures are put in place, good dental health can quickly be destroyed.

Conclusions

Patients seeking primary care on the west coast of Sweden have a high prevalence of xerostomia. Factors associated with xerostomia were female gender and medications and/or diseases. Awareness of the condition within medical and dental care is required to manage patients with xerostomia.

Author contributions

HCA and KM collected the data. HCA, BM, and KM contributed to the design of the study and supervision of AA. FL, HCA, and AA participated in the data description and statistical analysis. HCA wrote the original draft. All the authors participated in the reviewing and editing of the manuscript. This study was prepared as part of AA’s Ph.D. thesis.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Thomson WM, Chalmers JM, Spencer AJ, et al. The xerostomia inventory: a multi-item approach to measuring dry mouth. Commun Dent Health. 1999;16(1):12–17.

- Fox PC, Busch KA, Baum BJ. Subjective reports of xerostomia and objective measures of salivary gland performance. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115(4):581–584.

- Crockett DN. Xerostomia: the missing diagnosis? Aust Dent J. 1993;38(2):114–118.

- Thomson WM, Lawrence HP, Broadbent JM, et al. The impact of xerostomia on oral-health-related quality of life among younger adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4(1):86.

- Enoki K, Matsuda KI, Ikebe K, et al. Influence of xerostomia on oral health-related quality of life in the elderly: a 5-year longitudinal study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;117(6):716–721.

- Gerdin EW, Einarson S, Jonsson M, et al. Impact of dry mouth conditions on oral health-related quality of life in older people. Gerodontology. 2005;22(4):219–226.

- Villa A, Wolff A, Narayana N, et al. World workshop on oral medicine VI: a systematic review of medication-induced salivary gland dysfunction. Oral Dis. 2016;22(5):365–382.

- Pharmaceutical Specialties in Sweden [FASS]; 2013. Available from: http://www.fass.se/LIF/home/index.jsp

- Sreebny LM, Schwartz SS. A reference guide to drugs and dry mouth-2nd edition. Gerodontology. 1997;14(1):33–47.

- Agostini BA, Cericato GO, Silveira ERD, et al. How common is dry mouth? Systematic review and meta-regression analysis of prevalence estimates. Braz Dent J. 2018;29(6):606–618.

- Carpenter G. Dry mouth: a clinical guide on causes, effects and treatments; 2015.

- Jensen SB, Pedersen AM, Vissink A, et al. A systematic review of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia induced by cancer therapies: prevalence, severity and impact on quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(8):1039–1060.

- Orellana MF, Lagravere MO, Boychuk DG, et al. Prevalence of xerostomia in population-based samples: a systematic review. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66(2):152–158.

- Ying Joanna ND, Thomson WM. Dry mouth – an overview. Singapore Dent J. 2015;36:12–17.

- Nederfors T, Holmstrom G, Paulsson G, et al. The relation between xerostomia and hyposalivation in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis or fibromyalgia. Swed Dent J. 2002;26(1):1–7.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, STROBE Initiative, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–808.

- Field EA, Fear S, Higham SM, et al. Age and medication are significant risk factors for xerostomia in an English population, attending general dental practice. Gerodontology. 2001;18(1):21–24.

- Agha-Hosseini F, Mirzaii-Dizgah I, Mansourian A, et al. Relationship of stimulated saliva 17beta-estradiol and oral dryness feeling in menopause. Maturitas. 2009;62(2):197–199.

- Forsblad-d'Elia H, Carlsten H, Labrie F, et al. Low serum levels of sex steroids are associated with disease characteristics in primary Sjogren's syndrome; supplementation with dehydroepiandrosterone restores the concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(6):2044–2051.

- da Silva L, Kupek E, Peres KG. General health influences episodes of xerostomia: a prospective population-based study. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2017;45(2):153–159.

- de Almeida PDV, Grégio AMT, Brancher JA, et al. Effects of antidepressants and benzodiazepines on stimulated salivary flow rate and biochemistry composition of the saliva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106(1):58–65.

- Patel PS, Ghezzi EM, Ship JA. Xerostomic complaints induced by an anti-sialogogue in healthy young vs. older adults. Spec Care Dentist. 2001;21(5):176–181.

- Hopcraft MS, Tan C. Xerostomia: an update for clinicians. Aust Dent J. 2010;55(3):238–244; quiz 353.

- Elad S, Heisler S, Shalit M. Saliva secretion in patients with allergic rhinitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;141(3):276–280.

- Endly DC, Miller RA. Oily skin: a review of treatment options. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10(8):49–55.

- Scully C. Drug effects on salivary glands: dry mouth. Oral Dis. 2003;9(4):165–176.