Abstract

Objective: The study aimed to analyse the usefulness of signalling waiting times to citizens on the websites of public primary oral healthcare providers in Finland. Finnish laws require this signalling.

Material and methods: We gathered data with two cross-sectional surveys in 2021. One electronic questionnaire was for Finnish-speaking citizens in Southwest Finland. The other was for public primary oral healthcare managers (n = 159). We also gathered data on 15 public primary oral healthcare providers’ websites. For the theoretical framework, we combined the agency and signalling theories.

Results: Of the citizen respondents (n = 411), 57% knew about the waiting time signalling on the websites. The respondents considered waiting time a high-priority criterion in choosing a dentist, but they rarely searched for information anywhere on the choice of a dentist, wanting to visit the dentist they had earlier visited. The quality of signalled waiting times was low. One out of five managers (response rate 62%) answered that signalled waiting times were based on speculation.

Conclusions: Waiting times were signalled to comply with the legislation rather than to inform citizens and to reduce information asymmetry. Further research is needed to acquire information on rethinking waiting time signalling and its desired goals.

Introduction

Information asymmetry is typical in healthcare [Citation1]. The area is full of different agencies. Agency between two parties refers to one party, the agent, acting for the other, the principal, in a particular domain of decision problems [Citation2]. Agency problems emerge if the parties have different goals and the principal cannot determine whether the agent behaves appropriately [Citation3]. Agency problems are common; they exist in all cooperative efforts and all organizations [Citation4].

In healthcare, there are three major parties: citizens, healthcare providers, and state actors, meaning politicians and government officials [Citation5]. Citizens are healthcare clients who intend to use, use, or have used health services [Citation6]. Citizens also are members of communities, and they may or may not be interested in public issues and taking a stance on them.

Between these three parties, three agency relationships can be distinguished [Citation5]. The relationship between citizens, the principals, and the state actors, the agents, is based on a voting system expressing citizens’ demands to state actors and the state actors’ responsiveness to these demands. In the relationship between state actors and healthcare providers, the state actors are the principals, and they provide resources and specify objectives for the healthcare providers, the agents. Conversely, healthcare providers must provide state actors with information on how the objectives have been reached. In the third relationship, the citizens are the principals, and they convey their health needs regarding services to the service providers, the agents, who try to satisfy these needs.

All three parties agree that better health is the primary goal of healthcare actions. There are also non-health aspects of citizens’ expectations that need a response. These expectations include, e.g. reasonable waiting times for non-urgent care and a choice of a provider [Citation7,p.22–46]. In primary care, waiting time has been defined as waiting to see a healthcare professional [Citation8]. In hospital care, three waiting periods are used: waiting to see a specialist, waiting for hospital treatment and total waiting time [Citation9].

Waiting time for hospital treatment is the quality issue signalled most frequently to citizens [Citation10]. Also, other quality issues, such as rates of complications and patient satisfaction, are signalled. Citizens should receive information for conscious decision-making on their care [Citation11]. This decision-making is quite complex, and citizens do not base their decisions only on factual outcome indicators. Previous service experiences are essential in choosing a healthcare provider, e.g. a physician or a hospital [Citation12]. There is little evidence that citizens require increased possibilities to choose their healthcare provider except in cases where local health services are poor or have long waiting times [Citation13]. Public healthcare patients do not feel that enabling freedom of choice is a central issue. It would not be realistic or possible to enable freedom of choice in areas where the provision of general practitioners’ services is low [Citation14]. Overall, patients are loyal, but even the most loyal patients change service providers when the quality of the services significantly decreases [Citation15,p.76–105].

Waiting times may seem a straightforward indicator of healthcare actions. However, this is not the case. This indicator serves different purposes for different actors and is difficult to interpret. Incentives, norms and traditions influence how this indicator is processed and used [Citation16]. When waiting times are signalled to state actors for monitoring, the number of patients on the waiting list has been suggested as a measure [Citation17]. This indicator shows the provider’s current actions intended to keep waiting times reasonable. When signalling to citizens, the waiting times of treated patients can be used [Citation17]. Their interest is the total waiting time.

Studies during 2010–2019 in Canada [Citation18,Citation19] have found that citizens want to receive more information about waiting times for elective surgery and primary care. Information is likely valuable if it is at least somewhat more accurate than individuals’ prior knowledge [Citation20,p.319–352]. In 2020, study results from Italy indicated that it was not easy to find websites giving information on waiting times for outpatient visits of different kinds of public healthcare organizations, and the quality of this information tended to fluctuate [Citation21]. De Rosis et al. [Citation21] concluded that signalling waiting times was performed to comply with the law rather than provide information to citizens.

This study aims to analyse the usefulness of signalling waiting times to citizens on the websites of public primary oral healthcare providers in Finland. Usefulness requires that signalled waiting times positively influence citizens to reach the desired outcomes of oral healthcare providers. To positively influence citizens, waiting times should be signalled via easy-access means, and the signalled information should meet citizens’ decision-making needs. The research questions are the following: (1) Do citizens screen their environment for signals of waiting times for choices of a dentist? (2) What is the quality of signalled waiting times on the websites of public oral healthcare providers? (3) How does the management of oral healthcare providers perceive signalling waiting times to citizens?

The context of the study

In Finland, citizens can choose whether to use public or private oral healthcare services. Using private services is more expensive than using public services. If one chooses public sector services, there are some possibilities to choose the service provider, the unit and the dentist [Citation22]. The public sector provided about half of the adult dentist visits in 2020 [Citation23]. Based on the FinHealth 2017 study [Citation24,p.151–155], 52% of men and 67% of women visited a dentist regularly for check-ups. One out of five expressed that long waiting times made it difficult to access care, and one out of six said that the client fee was too high. About 2% felt it was difficult to travel to the dentist because of poor transport connections.

Long waiting times for non-urgent care are a problem of public oral healthcare. An appointment for urgent care is obtained without waiting. According to the care guarantee from 2005 [Citation25], a patient must get an appointment with a dentist within six months in non-urgent cases. In spring 2021, about 10% of the patients had to wait more than three months to see a dentist for non-urgent care [Citation26]. Citizens have considered that the waiting time for non-urgent public oral health services should be, at most, 46 days [Citation27].

The Finnish Healthcare Act [Citation22] requires that public service providers signal waiting times for non-urgent care on their websites. Waiting times should be signalled every fourth month by functional units. In signalling, for example, the third next available non-on-call dentist appointment time is used [Citation28]. This is preferred in primary care, as random cancellations in these cases do not have as much effect as on first available appointments [Citation29]. In 2003, it was suggested that a receptionist could count these waiting times daily or weekly [Citation29].

In 2020 [Citation30], 89% of Finnish households had access to the Internet at home. Health and nutrition information was searched on the Internet by 72% of Finnish citizens during the three-month period prior to the survey. Accordingly, 58% had used MyKanta, a digital service offering personal health data, prescription information and prescription renewals, and 50% had booked an appointment with a physician.

Theoretical framework

We derived the theoretical framework of our study () from agency theory [Citation2, Citation3] and signalling theory [Citation31]. Signalling theory is useful to describe the behaviour of two parties when there is information asymmetry between the parties, and both have access to different information [Citation32]. Signalling aims to reduce the information asymmetry between the parties–the signaller and the receiver–to positively influence the receiver to reach the desired outcomes of the signaller. Signalling theory has been used in studies on online activities [Citation33–36] and healthcare [Citation37–40].

Figure 1. The theoretical framework derived from agency [Citation2, Citation3] and signalling [Citation31] theories.

![Figure 1. The theoretical framework derived from agency [Citation2, Citation3] and signalling [Citation31] theories.](/cms/asset/d29f9f73-2ff2-411a-b150-4c2f148f7d28/iode_a_2204934_f0001_b.jpg)

In oral healthcare, the citizens (principals, receivers) decide on the provider (agent, signaller) whom they will visit, in principle. For this decision-making, citizens may screen their environment for information signals on the oral service providers’ attributes, such as professional competence, personality and the attitude of dentists [Citation41–44]. Criteria also used include service location [Citation45,Citation46], ability to obtain appointments at convenient times and reasonable waiting times for appointments [Citation42]. Costs may form barriers to using dental services [Citation46–48]. Citizens may trade off the choice criterion for another, for example, visiting their regular dentist and speed of access [Citation49]. In general, patients are loyal; only around one out of six will change their dentist if the circumstances, such as the address or the right to services, do not change [Citation50]. In a freedom-of-choice pilot in Finland, a citizen could choose private sector services with short waiting times and public client fees. The service use depended on subjective oral health [Citation51].

To screen for information on oral health services, family, friends and other dentists are important information sources [Citation42, Citation52]. Word of mouth has been [Citation53], and still is, a key means [Citation44]. Dental clinics’ websites are also used [Citation42, Citation54]. However, their usage is minor compared to the number of these websites. The role of social media is diverse. In one study, one-third of the respondents had used social media in choosing a dentist [Citation55], and in another study, social media did not play a significant role [Citation56]. In general, citizens seeking dental care use information sources they consider important [Citation42].

Oral healthcare providers can send out signals to help citizens to make decisions. These signals are mainly for marketing or public reporting purposes. Through marketing, healthcare providers try to attract citizens to care [Citation57], however, citizens seldom receive adequate information from these sources to evaluate the care they are receiving [Citation58, Citation59]. Public reporting provides citizens with factual performance data for decision-making. Citizens often consider this data too complex [Citation60]. To help citizens, performance indicators should be signalled via easy-access means and meet citizens’ decision-making needs [Citation61].

Materials and methods

To analyse the usefulness of signalling waiting times to citizens on the websites of public primary oral healthcare providers in Finland, we gathered data using two cross-sectional surveys during May and June 2021. One survey was for Finnish public primary oral healthcare managers and the other for citizens of Southwest Finland. The surveys were conducted using the software Webropol Survey & Reporting, Version 3.0. In addition, on 15 September 2021, we gathered waiting time data on the websites of public primary oral healthcare providers in Southwest Finland.

The Ethics Committee for Human Sciences at the University of Turku approved the study proposal in February 2021 (Permit July 2021). This ethical permit required that eligible participants were 18 years or older. In addition, the participants had to provide their informed consent to participate in the study. Therefore, each participant was asked to provide this consent at the beginning of the electronic questionnaire.

We also required a research permit from all public primary healthcare organizers in Finland for the manager survey. Applications for research permits were submitted to 135 organizers in March 2021. Of these, 48% had a population base of more than 20,000 inhabitants. We obtained permits from 105. Concerning the citizen survey, we obtained a research permit from all 15 public primary oral healthcare organizers of Southwest Finland.

Citizen survey

For the citizen survey, nonprobability convenience sampling was chosen, as forming a probability sampling of the citizens of Southwest Finland would have been prohibitively resource intensive. Thus, any Finnish-speaking adult who accessed the website of the study questionnaire in Finnish could participate in the study. Nonprobability sampling decreases the validity and credibility of study results, but the method is suitable for exploratory research to ascertain whether a problem exists or not [Citation62,p.17–32].

The officials of public primary healthcare organizers in Southwest Finland published electronic newsletters about the survey to inform citizens. These newsletters were published on the websites of these organizers at the beginning of May 2021, including a link to the survey website. In addition, if the healthcare organizers preferred, they could use other means such as social media for disseminating information. Furthermore, some of the chairpersons of the health and social services boards in the area were informed about the survey by phone or email.

To find out whether citizens screen their environment for signals of waiting times for choices of a dentist, we used 16 questions (). The questions, modified from similar surveys [Citation42, Citation45, Citation46], concerned the importance of waiting time in choosing a dentist and the sources used to search for information for this decision-making. In addition, we asked about waiting time signalling on the websites of public oral healthcare providers and the possibilities to access this information, as well as respondents’ personal information, such as gender, year of birth, education and use of oral health services.

Table 1. The citizen survey questions translated into English.

Gathering waiting time data

We gathered waiting time data on the websites of the 15 public primary oral healthcare providers of Southwest Finland on 15 September 2021. Finding relevant data on the websites was challenging. The data included the precision and unit of measurement of waiting time and the release date for signalling. We assessed the quality as low if the release date was earlier than 15 May 2021 or missing; this signalling was against the law as waiting times should be signalled every fourth month. The quality was also assessed to be low if imprecise wording, such as about, was used.

Manager survey

The research design included gathering data from every oral healthcare manager working in the public primary sector in Finland in the spring of 2021. As not all public primary healthcare organizers granted the research permit, we chose the managers for the study using convenience sampling. The number of managers of the 105 healthcare organizers included in our study was 159.

The survey was implemented in Finnish with an open Internet link to allow anonymous responses. The Internet link was sent to the contact persons of the oral healthcare organizations, detailed in the granted research permits, at the beginning of May 2021. Reminders to answer were sent at the end of May. Originally, we informed the oral healthcare managers that it would be possible to reply to the questionnaire by June 11. On June 2, the national waiting time website referred to in the survey was updated, resulting in us closing our questionnaire on that date. We sent a message regarding this to the oral healthcare organizations the next day.

The survey included six questions on managers’ perceptions of signalling waiting times to citizens on the websites (). Managers’ backgrounds, such as their degree and qualification, the number of years of management, and the population of the area they managed, were also surveyed as data to be used in other studies.

Table 2. The manager survey questions translated into English.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using the software IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0.0.0. In SPSS, the cases where data on a variable was missing were excluded from the analyses. The categorical data of the study enabled descriptive statistics to be predominantly used. Some data was gathered using a five-point Likert scale or another five-point ordinal scale. The distance between each response in the item of these scales was not considered to be equal, but this data was also handled as internal-level data, and means were calculated. This lack of equality of intervals has little impact on the statistical conclusions of studies, though parametric statistics are applied [Citation63,p.1–25].

Results

Citizens

Descriptive statistics

Four hundred and eleven citizens answered the questionnaire. Of these, 17 had answered the questions but did not provide informed consent to participate in the study. Thus, the number of respondents included in the analysis was 394. In addition, there was a minimal lack of data because not all respondents answered all questions. The number of respondents answering different questions varied from 385 to 394. In the case of each question, the number of valid responses (n) is separately reported.

Regarding gender, 87% of the respondents (n = 391) were women, and the age range was from 20 to 80 years (n = 385). Both the mean and the median ages were 49, 7% of respondents were younger than 30, and 4% were 70 or older. Twenty-one percent of the respondents (n = 393) had a master’s degree, 46% had a bachelor’s degree or college-level education, 30% had completed a vocational education or matriculation examination and 4% elementary or comprehensive school qualifications.

Sixty-five percent of the respondents (n = 393) visited a dentist regularly for check-ups, 28% visited a dentist irregularly and 7% only when suffering from a toothache or other problems. Fifty-three percent only used public oral services, while 7% only used private sector services (n = 393). The remainder, 40%, used both public and private oral health services in different proportions.

Importance of waiting time as an attribute

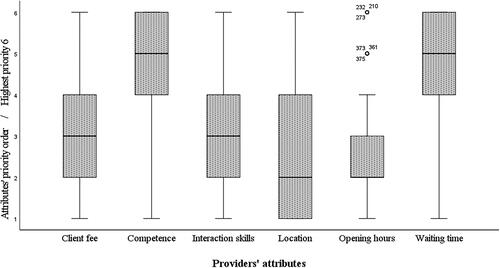

The respondents (n = 393) prioritized the attributes Competence of a dentist and Waiting time as the most important in choosing a dentist for non-urgent care ().

Figure 2. The priority of waiting time among providers’ attributes in citizens’ choices of a dentist for non-urgent care (n = 393).

The respondents (n = 393) agreed that short waiting times for non-urgent care are important in choosing a dentist. presents the variation of this importance by the personal information of the respondents. Of the respondents (n = 394), 62% agreed or strongly agreed that they could visit any dentist for non-urgent care if the waiting time is short.

Table 3. The importance of short waiting times for non-urgent dental care by the citizen respondents’ personal information.

Sources used for screening

In choosing a dentist, 15% of respondents often or almost always screened information from relatives, acquaintances and/or friends (n = 388). Information from these sources was never or rarely screened by 62%. The corresponding proportions for screening information from public service providers’ websites were 19% and 58% (n = 388), screening information from private service providers’ websites 16% and 63% (n = 386) and using social media 4% and 82% (n = 385). Seventy-three percent of the respondents (n = 392) agreed or strongly agreed that they do not screen any information from anywhere when choosing a dentist, booking appointments with dentists whom they have visited earlier.

Waiting times on the public service providers’ websites

Fifty-seven percent of the respondents (n = 394) knew that public providers signal waiting times for non-urgent oral healthcare on their websites. Of those, 71% had visited these websites, corresponding to 40% of all respondents. Sixty-nine percent of all respondents (n = 392) presumed that they could at least sometimes use signalled waiting time information in decision-making when choosing a dentist. Accordingly, 68% thought to use the information for assessing whether they got their appointment in line with signalled waiting times (n = 392). Ninety-three percent of the respondents (n = 390) considered signalling waiting times on the service providers’ websites useful. In contrast, 17% agreed or strongly agreed that the information does not interest anyone (n = 394).

Access to the websites

Only three of the citizen survey respondents could not access the Internet at home (n = 393). On a scale from 1 (very poor) to 7 (very good), they assessed their digital competence to be, on average, 5.9 (n = 391). The standard deviation was 1.1, the median 6 and the range 1–7. Of the respondents (n = 394), 27% searched the Internet for health information at least once a week, 29% searched once a month, 36% a couple of times a year and 8% never. Furthermore, 18% searched for information about health services at least once a week, 31% once a month, 45% a couple of times a year and 6% never (n = 394). Ten percent of the respondents (n = 393) used health applications, e.g. MyKanta, at least once a week, 38% once a month, 45% a couple of times a year and 7% never.

Quality of signalled waiting times

presents how the 15 public primary oral healthcare providers signalled waiting times on their websites on 15 September 2021.

Table 4. Waiting time indicators signalled on the websites of the 15 public primary oral healthcare providers on 15.9.2021.

Managers

Descriptive statistics

Ninety-eight of the 159 managers potentially participating in the study answered our questionnaire, a response rate of 62%. One of the managers had answered the questions but did not provide informed consent to participate in the study, so the number of managers included in the analysis was 97. There also was a minimal lack of data as not all the managers answered all questions. The number of respondents answering different questions varied from 91 to 97.

Sixty percent of the managers (n = 96) had a licentiate degree in dentistry, 20% were specialist dentists and 20% had other qualifications, for example, eight were dental hygienists. As managers, 40% had worked for 5 years or less, 16% from 6 to 10 years and 44% longer than 10 years (n = 93). Approximately half worked in organizations with a population base of up to 20,000 and the other half in organizations with a larger population base (n = 95).

Perceptions of signalling waiting times to citizens

Ninety percent of the managers (n = 96) perceived signalling waiting times for non-urgent dental care to citizens on the websites as useful. Only 41% presumed that the average durations of different dental treatment episodes should also be signalled to citizens (n = 97).

The managers (n = 92) estimated that, on average, 25% of the citizen respondents knew about waiting time signalling on the websites. The lower quartile was 10%, the median 20% and the upper quartile 35%. Furthermore, they (n = 91) estimated that, on average, 53% of the citizen respondents considered signalling waiting times useful. The lower quartile was 30%, the median 55% and the upper quartile 75%.

Processing waiting time information

Twelve percent of the managers (n = 96) answered that the electronic patient information system processed waiting time indicators. The indicators were processed manually using either the first or third next available appointment time according to the answers of 64% of the managers, and 18% answered that estimates by speculation were used. Eighty-eight percent of the organizations in which waiting times were estimated by speculation had a population base of up to 20,000. Seven managers did not know how the indicators were processed. Of these, two managed an organization with a population base of up to 20,000.

Ninety-five percent of the managers (n = 95) agreed or agreed strongly that electronic patient information systems should automatically process waiting time indicators.

Discussion

Our survey analysed the usefulness of signalling waiting times to citizens on the websites of public primary oral healthcare providers in Finland. Using websites to signal waiting times is effective, as most of the citizen respondents have access to the Internet and use it to search for health information. Approximately 60% of the citizen respondents knew about this signalling, and about 70% presumed that they at least sometimes could use the information. The citizen respondents considered waiting time a high-priority criterion when choosing a dentist for non-urgent care. In practice, they had minimal need to search for any information for decision-making, preferring to visit the dentist they had earlier visited. Also, the choice possibility when using public services was minor. Though the managers perceived signalling waiting times on the websites as useful, the quality of signalled waiting times was low. Approximately one out of five managers answered that the signalled information was estimated by speculation. The study results indicated that waiting times were signalled to comply with Finnish legislation rather than to reduce the information asymmetry between citizens and oral healthcare providers.

We derived the theoretical framework of our study from the agency theory [Citation2, Citation3] and signalling theory [Citation31]. The framework worked well to analyse the usefulness of waiting time signalling in the study context. As a result of information asymmetry between citizens (principals) and oral healthcare providers (agents), citizens, unlike providers, do not know the attributes of providers, such as waiting times for accessing care, to influence decision-making in choosing a dentist. To reduce information asymmetry, providers can signal some attributes to citizens to achieve the desired outcomes of providers, such as increasing the clientele. The content and means of signalling should be the ones that citizens consider useful and can and will use for decision-making.

Waiting time information was a high-priority criterion in choosing a dentist for non-urgent care in our study, as in previous studies [Citation42]. Less than one-fifth of the citizen respondents often or almost always searched for information for this decision-making. The citizen respondents did not need to search for information, as they wanted to visit the dentist they had visited earlier, perhaps based on their previous service experiences [Citation12]. Previous studies have also emphasized patients’ loyalty to their dentists [Citation50]. Getting information from family and friends by word of mouth has been a standard method of obtaining information in earlier literature [Citation42,Citation44,Citation52,Citation53]. This was also visible in our study, though the respondents used private and public service providers’ websites a little more.

We agreed with the conclusions of De Rosis et al. [Citation21]. Also, in Finland, providers signalled waiting times on the websites to comply with the law rather than to provide information to citizens. The quality of the signals was low: one-third were imprecise, giving timeframes such as ‘two-three months’. One-third missed the release date, or the date was not within four months, as specified by law [Citation22]. The researchers did not easily find this information on the providers’ websites.

The fact that public oral healthcare providers had no strategic goals for signalling may explain the low-quality waiting time information. Providers did not need to increase their clientele and competition with private and other public providers was minimal. For some citizens, client fees form barriers to using private services [Citation24,Citation46–48]. Choosing another public service provider may be difficult because of poor transport connections [Citation24], or it may increase traveling time and costs. Based on other studies, public healthcare patients do not consider freedom of choice as a central matter, especially in sparsely populated areas [Citation13,Citation14].

Practical implications

The citizen respondents perceived waiting time signalling on the websites as useful, though the need for waiting time information was minor. They could access the Internet at home, and many used it to search for health information. The websites were a proper means to signal waiting times. However, the low-quality information was a problem. Every oral healthcare provider had an electronic patient information system, but only about 10% used the system to calculate the waiting times.

In these systems, providers have the data required to calculate waiting time indicators [Citation64]. Supplementing the systems with proper functionalities would enable the automatic calculation of waiting times to be published daily on the websites. The information could be categorized by all attributes, such as the dentist, recorded into the systems. Different statistical key figures, such as the mean and median of waiting time, could be calculated. Providers could get accurate information on the waiting times of those patients who received an appointment on the day in question. Of course, cancellations should be taken into consideration. For automatic calculations, oral healthcare providers need national definitions, specifications for electronic patient information systems and instructions for personnel. A dental nurse should no longer use worktime to calculate the third next available appointment time [Citation28, Citation29], instead, providers should use automatic data management.

Limitations and future research

Our study is not without limitations. With a cross-sectional survey, we can never verify any causality. As convenience sampling was used, it decreased the validity and credibility of the study results [Citation62]. The challenge is that the respondents taking part in the study may be those who have a very positive or negative view of the studied issue. It is easier to arouse their attention to participate than to arouse the interest of others. In our citizen study, the method of informing about the survey may also have caused bias in the results; some political decision-makers of the area were informed more personally about the survey than other citizens. The proportions of the citizen respondents knowing of and visiting websites signalling waiting times were probably higher than with probability sampling. It is also probable that citizens taking part in electronic surveys have better digital competence and easier access to the Internet and electronic services than citizens on average. Finally, although we would have used probability sampling, the possibility to generalize the study results to other environments is restricted. The healthcare systems and social and cultural aspects differ remarkably by country.

Access to non-urgent dental care within a reasonable time is essential for citizens [Citation7]. The participants in our study were ready to visit any dentist for non-urgent care if the waiting time for access to care was short. Reducing waiting times is also a key objective in the healthcare strategies of many countries. However, speeding up access to dental care may lengthen dental treatment episodes. It is easy to speed up access to care by lengthening the intervals between other visits required for the dental treatment episode of a patient. Instead of focusing only on speeding up access to care, methods of keeping the durations of the dental treatment episodes reasonable should be analysed. In addition, how providers should signal the average durations of different dental treatment episodes to citizens should be studied. It is the total waiting time, indicating the waiting time to access dental care plus the duration of the dental treatment episode, that is in the interest of a citizen.

Conclusions

Signalling waiting times on the websites of public primary oral healthcare providers should reduce information asymmetry between citizens and providers. Though many citizens participating in the study knew about waiting time signalling on the websites, they did not search for this information as it was not required in choosing a dentist. Citizens generally wanted to visit the dentist they had earlier visited, and the possibilities to choose a dentist in the public sector were limited. The public providers had no strategic goals for this signalling, and the quality of waiting time information was low. Signalling was primarily to comply with Finnish laws. Further research is needed to acquire information on rethinking waiting time signalling in oral healthcare and its desired goals.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Finnish public primary healthcare organizers for enabling the study. In addition, the authors thank the officials of the organizers of public primary healthcare in Southwest Finland for disseminating information of the study to citizens by different media.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

According to the privacy policy, the researcher can process the survey data for the time required for her thesis. During the time, the data will not be transferred outside the University of Turku. After that, the data without the credentials is disclosed to the Finnish Social Science Data Archive without conditions for the use of the disclosed materials.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arrow K. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. Am Econ Rev. 1963;53(5):941–973.

- Ross S. The economic theory of agency: the principal’s problem. Am Econ Rev. 1973;63(2):134–139.

- Eisenhardt K. Agency theory: an assessment and review. Acad Manage Rev. 1989;14(1):57–74.

- Jensen M, Meckling W. Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ. 1976;3(4):305–360.

- Brinkerhoff D, Bossert T. Health governance: principal–agent linkages and health system strengthening. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(6):685–693.

- Street J, Stafinski T, Lopes E, et al. Defining the role of the public in health technology assessment (HTA) and HTA-informed decision-making processes. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2020;36(2):87–95.

- World Health Organization. World health report 2000. Health systems: improving performance. Albany (NY): World Health Organization; 2000. Chapter 2, How well do health systems perform?; p. 22–46.

- Martin S, Siciliani L, Smith P. Socioeconomic inequalities in waiting times for primary care across ten OECD countries. Soc Sci Med. 2020;263:113230–113230.

- Sanmartin CA, Noseworthy T, Barer ML, et al. Toward standard definitions for waiting times. Healthc Manage Forum. 2003;16(2):49–53.

- Rechel B, McKee M, Haas M, et al. Public reporting on quality, waiting times and patient experience in 11 high-income countries. Health Policy. 2016;120(4):377–383.

- Øvretveit J. Quality evaluation and indicator comparison in health care: quality evaluation. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2001;16(3):229–241.

- Victoor A, Delnoij D, Friele R, et al. Determinants of patient choice of healthcare providers: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):272–272.

- Fotaki M, Roland M, Boyd A, et al. What benefits will choice bring to patients? Literature review and assessment of implications. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13(3):178–184.

- James O, John P. Testing Hirschman’s exit, voice, and loyalty model: citizen and provider responses to decline in public health services. Int Public Manag J. 2021;24(3):378–393.

- Hirschman A. Exit, voice, and loyalty responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1970. Chapter 7, A theory of loyalty; p. 76–105.

- Stoop A, Vrangbaek K, Berg M. Theory and practice of waiting time data as a performance indicator in health care. A case study from the Netherlands. Health Policy. 2005;73(1):41–51.

- Siciliani L, Moran V, Borowitz M. Measuring and comparing health care waiting times in OECD countries. Health Policy. 2014;118(3):292–303.

- Bruni R, Laupacis A, Levinson W, et al. Public views on a wait time management initiative: a matter of communication. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):228–228.

- Johnston S, Abelson J, Wong S, et al. Citizen perspectives on the use of publicly reported primary care performance information: results from citizen-patient dialogues in three Canadian provinces. Health Expect. 2019;22(5):974–982.

- Gowrisankaran G. Competition, information provision, and hospital quality. In: Sloan FA, Kasper H, editors. Incentives and choice in health care. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2008. p. 319–352.

- De Rosis S, Guidotti E, Zuccarino S, et al. Waiting time information in the italian NHS: a citizen perspective. Health Policy. 2020;124(8):796–804.

- Finlex Data Bank [Internet]. Terveydenhuoltolaki 31.12.2010/1326 [Health care act 31.12.2010/1326]; [cited 2022 Sep 14]. Available from: Terveydenhuoltolaki 1326/2010 - Ajantasainen lainsäädäntö - FINLEX ®. Finnish.

- Sotkanet.fi: Statistical information on welfare and health in Finland [Internet]. Oral health care visits. Helsinki: National Institute for Health and Welfare; 2005–2022; [cited 2022 Feb 5]. Available from: https://sotkanet.fi/sotkanet/en/haku?g=470

- Suominen L, Raittio E. Suun terveydenhuolto [oral healthcare]. In: Koponen P, Borodulin K, Lundqvist A, et al. editors. Terveys, toimintakyky ja hyvinvointi suomessa. Finterveys 2017 -tutkimus. Raportti 4/2018 [Health, functional capacity, and welfare in Finland. FinHealth 2017 study. Report 4/2018]. Helsinki (Finland): Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos; 2018. p. 151–155. Finnish.

- Finlex Data Bank [Internet]. Laki kansanterveyslain muuttamisesta 17.9.2004/855 [Act for changing public health act 17.9.2004/855]; [cited 2022 May 20]. Available from: Laki kansanterveyslain muuttamisesta 855/2004 - Säädökset alkuperäisinä - FINLEX ®. Finnish.

- Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos. Tilastoraportti 21/2021 07.06.2021. Hoitoonpääsy perusterveydenhuollossa keväällä 2021. [Statistical report 21/2021 07.06.2021. Access to primary health care in spring 2021]; [cited 2022 May 2]. Available from: https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/142680/TR_21_2021.pdf?sequence =8&isAllowed=y. Finnish.

- Tuominen R, Eriksson A-L. Patient experiences during waiting time for dental treatment. Acta Odontol Scand. 2012;70(1):21–26.

- Salkinoja P, Tuononen T, Suominen AL, et al. Oral health care quality as viewed by leading dentists and their superiors - a qualitative study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2022;80(1):38–43.

- Murray M, Berwick DM. Advanced access: reducing waiting and delays in primary care. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289(8):1035–1040.

- Tilastokeskus Suomen virallinen tilasto [Official Statistics of Finland]. Tiede, teknologia ja tietoyhteiskunta 2020. Väestön tieto- ja viestintätekniikan käyttö 2020 [Science, technology, and the information society 2020. Use of ICT by the population 2020]; [cited 2022 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.stat.fi/til/sutivi/2020/sutivi_2020_2020-11-10_fi.pdf. Finnish.

- Spence M. Job market signaling. Q J Econ. 1973;87(3):355–374.

- Connelly B, Certo S, Ireland R, et al. Signaling theory: a review and assessment. J Manage. 2011;37(1):39–67.

- Basoglu K, Hess T. Online business reporting: a signaling theory perspective. J Inf Sys. 2014;28(2):67–101.

- Mavlanova T, Benbunan-Fich R, Koufaris M. Signaling theory and information asymmetry in online commerce. Inf Manag. 2012;49(5):240–247.

- Rao S, Lee K, Connelly B, et al. Return time leniency in online retail: a signaling theory perspective on buying outcomes. Decis Sci. 2018;49(2):275–305.

- Boateng S. Online relationship marketing and customer loyalty: a signaling theory perspective. Int J Bank Market. 2019;37(1):226–240.

- Fletcher-Brown J, Pereira V, Nyadzayo M. Health marketing in an emerging market: the critical role of signaling theory in breast cancer awareness. J Bus Res. 2018;86:416–434.

- Li J, Tang J, Jiang L, et al. Economic success of physicians in the online consultation market: a signaling theory perspective. Int J Electron Commer. 2019;23(2):244–271.

- Mou J, Shin D. Effects of social popularity and time scarcity on online consumer behaviour regarding smart healthcare products: an eye-tracking approach. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;78:74–89.

- Yang H, Du H, Shang W. Understanding the influence of professional status and service feedback on patients’ doctor choice in online healthcare markets. Internet Res. 2021;31(4):1236–1261.

- Crane F, Lynch J. Consumer selection of physicians and dentists: an examination of choice criteria and cue usage. J Health Care Mark. 1988;8(3):16–19.

- Kim M, Damiano P, Hand J, et al. Consumers’ choice of dentists: how and why people choose dental school faculty members as their oral health care providers. J Dent Educ. 2012;76(6):695–704.

- Lamprecht R, Struppek J, Heydecke G, et al. Patients’ criteria for choosing a dentist: comparison between a university-based setting and private dental practices. J Oral Rehabil. 2020;47(8):1023–1030.

- Ungureanu M-I, Mocean F. What do patients take into account when they choose their dentist? Implications for quality improvement. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1715–1720.

- Coe J, Qian F. Consumers’ choice of dentist by self-perceived need. Int J Pharm Healthc Mark. 2013;7(2):160–174.

- Gray L, McNeill L, Yi W, et al. The “business” of dentistry: consumers’ criteria in the selection and evaluation of dental services. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0253517.

- Listl S. Cost-related dental non-attendance in older adulthood: evidence from eleven European countries and Israel. Gerodontology. 2016;33(2):253–259.

- Thompson B, Cooney P, Lawrence H, et al. Cost as a barrier to accessing dental care: findings from a Canadian population-based study: cost as a barrier to accessing dental care. J Public Health Dent. 2014;74(3):210–218.

- Campbell S, Tickle M. What is quality primary dental care? Br Dent J. 2013;215(3):135–139.

- Lucarotti P, Burke F. Factors influencing patients’ continuing attendance at a given dentist. Br Dent J. 2015;218(6):e13.

- Raittio E, Torppa-Saarinen E, Sokka T, et al. Association of service use with subjective oral health indicators in a freedom of choice pilot. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2023;9(1):134–141.

- Chakraborty G, Gaeth G, Cunningham M. Understanding consumers’ preferences for dental service. Mark Health Serv. 1993;13(3):48.

- Mangold W, Abercrombie C, Berl R, et al. Reaching patients who are new to the community. J Dent Pract Admin. 1990;7(2):79–84.

- Clow K, Stevens R, McConkey C, et al. Attitudes of dentists and dental patients Toward advertising. Health Mark Q. 2007;24(1-2):23–34.

- Tengilimoglu D, Sarp N, Yar C, et al. The consumers’ social media use in choosing physicians and hospitals: the case study of the province of Izmir. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2017;32(1):19–35.

- Parmar N, Dong L, Eisingerich A. Connecting with your dentist on facebook: patients’ and dentists’ attitudes towards social media usage in dentistry. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(6):e10109.

- Crié D, Chebat J-C. Health marketing: toward an integrative perspective. J Bus Res. 2013;66(1):123–126.

- Andreasen A. Consumerism and health care marketing. Calif Manage Rev. 1979;22(2):89–95.

- Kay M. Healthcare marketing: what is salient? Int J Pharm Healthc Mark. 2007;1(3):247–263.

- Pross C, Averdunk L-H, Stjepanovic J, et al. Health care public reporting utilization - user clusters, web trails, and usage barriers on Germany’s public reporting portal Weisse-Liste.de. BMC Medical Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17(1):48–48.

- Prang K-H, Maritz R, Sabanovic H, et al. Mechanisms and impact of public reporting on physicians and hospitals’ performance: a systematic review (2000-2020). PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0247297.

- Henry G. Practical sampling. Newbury Park (CA): SAGE; 1990. Chapter 2, Sample selection approaches; p. 17–32.

- Cohen B. Explaining psychological statistics. 4th ed. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons Incorporated; 2013. Chapter 1, Introduction to Psychological Statistics; p. 1–25.

- Häkkinen P, Mölläri K, Saukkonen A-M, et al. Hilmo - Sosiaali- ja terveydenhuollon hoitoilmoitus 2020: Määrittelyt ja ohjeistus: Voimassa 1.1.2020 alkaen [Hilmo - Social and healthcare treatment notice 2020: Definitions and instructions: Valid from 1 January 2020]. Helsinki: Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos2019; [cited 2022 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.julkari.fi/handle/10024/138288. Finnish.