Abstract

Background The evaluation of a total hip prosthesis would be most complete if the opinion of the patient, surgeon and the radiographs are combined. Disease specific patient outcome questionnaires are scarce, especially in Dutch.

Methods The disease-specific 12-item questionnaire on the perception of patients with total hip replacement was translated into Dutch. We also investigated the extra value of two specific hip items, “the need for walking aids” and “sexual problems because of the hip”, four general items on overall satisfaction and one question about patient classification. The 14 hip-specific items were each scored from 1 (least difficulties) to 5 (most difficulties). The Dutch translation, the “Oxford Heup Score” (OHS) was tested on psychometric quality in a multicenter prospective study.

Results The psychometric results of the OHS proved to be adequate. In the first postoperative year the score was very sensitive to changes, whereas in the second year it did not change significantly. The two added hip-specific questions were both filled out positively by more than 50% of the patients and thus fit perfectly into a hip-specific patient outcome questionnaire such as the OHS.

Interpretation The OHS proves to be an appropriate instrument for assessment of the outcome of total hip replacement from the patient's perspective. Together with the judgement of the surgeon, it provides useful insights into the question of whether this operation has been a success or not.

The opinion of the patient plays an important role in grading the result of a total hip arthroplasty (Lieberman et al. Citation1996). Until now, most questionnaires have been based on the opinion of the surgeon, such as the Harris Hip Score and the Merle d'Aubigné score (Merle d'Aubigné and Postel Citation1954, Harris Citation1969). Questionnaires which specifically measure the result of a total hip replacement from the point of view of the patient are relatively scarce, especially in the Dutch language. Usually translated versions of generic questionnaires that have been validated are used, such as the RAND36, a visual analog scale for pain, and the Nottingham Health Profile (Carlsson Citation1983, Van der Zee and Sanderman 1993a, Van der Zee et al. Citation1993). As opposed to disease-specific questionnaires, generic questionnaires concentrate on the general health of the patient. These questionnaires can be used under various conditions, but are not very sensible for disease-specific sensitive to disease-specific changes.

In 1996, we decided to translate the disease-specific “12-item questionnaire” for the patient with THA into Dutch and to evaluate it. This questionnaire was published that same year (Dawson et al. Citation1996a) and contains 12 questions for evaluation of pain and hip function in relation to various activities. Each question contains 5 quantifiable answering possibilities, leading to a total score that can range between 12 (least problems) and 60 (most problems). The original English version of the 12 item questionnaire has been tested for psychometric quality (Dawson et al. Citation1996a, Citationb, Citationc, Fitzpatrick and Dawson Citation1997).

Based on experience with hip patients, we also determined whether the addition of 2 disease-specific items and 5 general questions to the Dutch version of the 12-item questionnaire would be of benefit. The two disease-specific items were “the use of walking aids when walking” and “problems with sexual activity because of the hip” (Stern et al. Citation1991, Wright et al. Citation1994, Currey Citation1997). Of the 5 general questions that we added, 4 required the general opinion of the patient (Johnston et al. Citation1990). The fifth question reflected the division in different Charnley classes (Charnley Citation1972). The latter 5 questions were not included in the total score because they were not disease-specific ().

Table 1. The five general questions

Here we report the internal consistency, reproducibility, construct validity and sensitivity to change of the “Oxford Heup Score” (OHS).

Methods

The study was divided in two phases: firstly, the original 12-item questionnaire was translated into Dutch and then this version with the added questions was tested for psychometric quality in a prospective project involving 150 patients.

Translation procedure

4 people from different centers, working independently, translated the English version of the 12-item questionnaire into Dutch. This version was reviewed by a bilingual person with English as her mother tongue. Without having seen the original questionnaire, she was asked to translate the Dutch version back into English. The similarities and differences between the original, the translated and the re-translated versions were discussed and incorporated into a revised version in Dutch. The complete questionnaire was then tested on 15 patients with hip problems who had attended the three participating hospitals, and was then adjusted to form the definitive version of the OHS.

Prospective trial concerning psychometric quality

To test the psychometric quality of the OHS, we performed a prospective trial in 150 patients with hip disease. All patients met the inclusion criteria of this study ().

Table 2. Patient inclusion criteria

The patients who were included (98 women) had a mean age of 65 (38–85) years and were from the Academic Hospital Maastricht (n = 57), the University Medical Center (n = 41) and the Rijn-land Hospital (n = 52). The reason for operation was primary arthrosis in 78% of cases. In 62%, a cemented total hip arthroplasty (THA) was performed, and a cementless THA was performed in the remaining 38%. Different kinds of prostheses were used: SHP 22%, Osteonics cemented 18%, Osteonics HA-coated 17%, Exeter 20%, Müller 3%, Mallory Head HA-coated 12%, AML 3% and Zweymüller 5%. The OHS was presented to the patients preoperatively and postoperatively at 7 weeks and at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months. For reasons of organization, the Rijnland Hospital was forced to abandon the examination at 7 weeks. All patients gave their informed consent.

The OHS was investigated for reproducibility, internal consistency, construct validity and sensitivity to change. The same set-up and statistical methods were used as with the validation of the original version, with the exception of the follow-up period, which was extended to 2 years in this trial.

Reproducibility

The reproducibility was investigated by calculating the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC, two-way random model for agreement) between the test and the re-test (McGraw and Wong Citation1996). We asked 42 of the patients included to answer the questionnaire again within 24 hours, to see whether they completed it with the same answers. We assumed that their hip problems had not changed in the interim period. In addition, the “borders of similarity” were calculated according to the method of Bland and Altman (Bland and Altman Citation1996). We included these because they provide insight into the source of the noise. An intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) is a coefficient between 1 and 0 and does not tell how much on a scale a repeated measure may differ. Although the Bland and Altman method was orginally designed to compare different methods, it can also be applied to determine the reproducibility of a measurement (Bland and Altman Citation1996).

Internal consistency

The internal consistency was calculated via Cron-bach's (Citation1951) alpha. This is a summarizing value (range 0.0–1.0) which is based on the correlations between the separate questions and the overall score. With this test, we also investigated whether the value of alpha could increase by removing individual questions.

Construct validity

The validity of the OHS was determined by comparing its results with various subscales of the generic RAND-36 (because we lacked a disease-specific questionnaire in the Dutch language) and the VAS for pain, to test whether the OHS actually measured the problems of the patient with a THA. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated. The VAS for pain was filled in by the patient at every follow-up; the RAND-36 preoperatively and also postoperatively at 6 months.

To investigate whether the OHS of satisfied patients differed from the OHS of dissatisfied patients, the scores of every postoperative follow-up occasion were compared with each other.

Convergent and divergent validity were measured by investigating the strength of the correlation coefficients. The OHS should converge, have high correlations, with similar metrics (e.g. VAS for pain, physical functioning) and diverge, have low correlations, from dissimilar domains from the RAND-36 (e.g. general perception of health, mental health).

Sensitivity to change

The sensitivity of the score to changes is expressed in effect size (difference in means divided by SD of the baseline score), calculated by the method of Kazis, between the preoperative score and the postoperative score at 6 months, 1 year and 2 years follow-up (Kazis et al. Citation1989). An effect size above 0.8 is considered to be large, between 0.5 and 0.8 to be moderate, and below 0.5 to be small. This comparison was also made between the pre-and postoperative RAND-36 score at 6 months follow-up.

Results

During the total follow-up period, the OHS was not completed at all on 25 occasions. In 20 other questionnaires, the total score could not be calculated since not all questions were answered. In 18 of these cases, this involved the question concerning “problems with sexual activity because of the hip”.

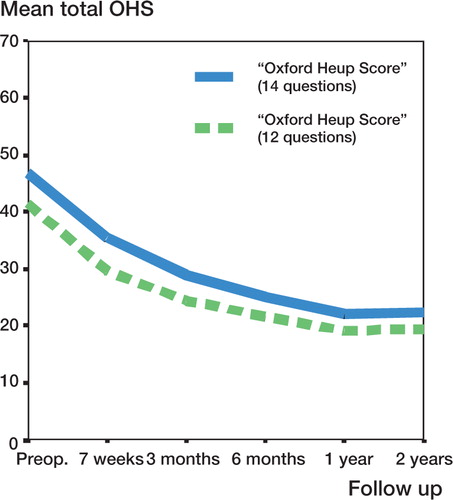

The mean preoperative OHS was 40 and the mean postoperative OHS was 31 at 7 weeks, 25 at 3 months, 21 at 6 months, and 19 at both 1 and 2 years. The mean total score of the original 12-question version followed a comparable trend when the two extra questions were added, and the corresponding values for OHS were 47, 36, 29, 25, 22 and 22, respectively ().

Preoperatively, 65% of the patients ‘sometimes to always’ used a walking aid, while postoperatively this figure dropped to 45% at 6 months, to 31% at 1 year and finally increased slightly to 35% at 2 years. Problems with sexual activitiy because of the hip were noticed preoperatively by 57% of the patients and postoperatively by 22% at 60 months, by 18% at 1 year and by 24% at 2 years of follow-up ().

Table 3. Answers to the supplementary disease-specific questions: values are percentage per follow-up

Up to 2 years postoperatively, most patients noted that their hip function had improved and that their hip pain had been reduced by the operation. The question of whether the patient was satisfied with the operation was answered in a positive way by 92% of the patients at 6 months follow-up, by 94% at 1 year and by 90% at 2 years. Comparison of the hip function with the previous follow-up was judged to be worse by 6% of the patients at 6 months follow-up, by 4% at 1 year and by 8% at 2 years ().

Table 4. Answer to the four added general questions: values are percentage per follow-up

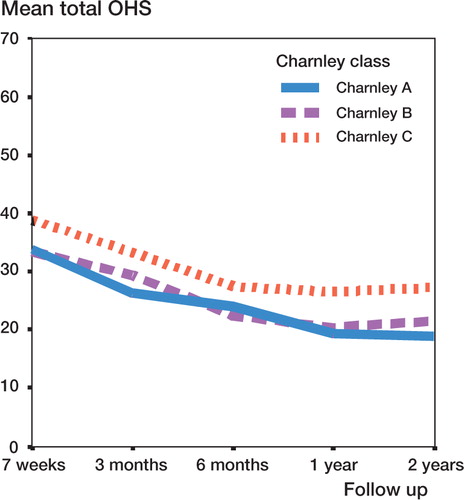

The patients were divided into the Charnley classes as follows: 42% class A, 24% class B and 34% class C. The mean OHS was best in class A, followed by B and then C. From 3 months onwards, there was a significant difference between the three Charnley classes in their mean total OHS. This significant difference was seen between classes A and C, and between classes B and C, but not between class A and class B ().

The mean VAS score for pain was 6.7 preoperatively and 2.1 at 6 months postoperatively, and 1.6 at both the 1-year and the 2-year follow-up.

Reproducibility

The test-retest (n = 42) showed an ICC of 0.97 (95% CI: 0.95–0.98). 95% of the differences in the scores were between -2.7 and +2.7 on a scale of 12–60 points.

Internal consistency

Cronbach's alpha varied from 0.84 preoperatively to 0.89 at 6 months postoperatively, 0.93 at 1 year and 0.92 at 2 years. All questions correlated with the total score from r = 0.4–0.9, except the question about problems with sexual actvity because of the hip (range r = 0.2–0.4). The value of alpha was not influenced by removal of this question, however.

Construct validity

Both the preoperative OHS and the postoperative OHS at 6 months correlated significantly with the scores of the RAND-36. Low correlations, or divergent validity, (r < 0.35) were obtained preoperatively on the items: decrease of emotional role, perception of general health and changes in general health, and postoperatively on mental health, vitality and perception of general health. High correlations, or convergent validity, (r ≥ 0.7) were obtained both pre- and postoperatively on the items physical function and pain, and postoperatively also on decrease of physical role. The correlation between the OHS and the VAS for pain was also very high on all follow-up occasions (r ≥ 0.7).

At every follow-up occasion, a statistically significant difference was found between the total score of satisfied patients and those who were dissatisfied about the result of the operation. The same difference was found between patients who judged that their hip pain had decreased and those who thought the pain had not decreased. Satisfied patients and patients with less pain had a higher OHS. This significant difference was also seen between those patients who thought the mobility of their hip had increased and those who thought it had not, with the exception of the result at 7 weeks follow-up. Regarding these results, it should be noted that most patients were satisfied (between 89% and 95%), so the groups to be compared were unevenly divided.

Sensitivity to change

The “effect size” in the OHS between the preoperative and postoperative follow-up of 6 months, 1 year and 2 years were 2.38, 2.68 and 2.65, respectively. An effect size above 0.8 was considered to be large, between 0.5 and 0.8 to be moderate, and below 0.5 to be small (Cohen 1977). For the items of the RAND-36, at 6 months these were: physical functioning 1.63, social functioning 1.01, decrease in role (physical problem) 1.59, decrease in role (emotional problem) 0.84, mental health 0.54, vitality 0.63, pain 2.28, general perception of health 0.04, and change in health 1.69.

Discussion

It is not sufficient to simply translate a questionnaire into a foreign language without validating the translated version (Guillemin et al. Citation1993, Guyatt Citation1993). The translation process we used follows the general guidelines given by Guillemin et al. (Citation1993). The complete questionnaire appeared to be completed by the patients quite easily, and this resulted in a small proportion of missing values (Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2000). The two added questions about “the use of walking aids” and “problems with sexual activity because of the hip” showed problems in more than half of the patients before the operation. This illustrates the importance of these items for total hip arthroplasty patients; thus, these questions should be included in a disease-specific questionnaire for such patients. The internal consistency dropped slightly because of the low correlation between the question about “problems with sexual activity because of the hip” and the total score. One possible explanation might be that the physical stress in this item is different from the other items of the OHS. Another argument for not including this question in the score is that 18/150 cases did not complete this specific question. On the other hand, Cronbach's alpha increased only marginally by removing this question.

In comparing the OHS with the items of RAND36, the largest correlation was seen with the items “physical functioning”, “pain” and “decrease of role by physical problems”. A high correlation was also seen with the VAS for pain. Thus, one can conclude that these important parameters were measured by the OHS (Liang et al. Citation1982, Britton et al. Citation1997).

The four general questions showed that satisfied patients had a higher OHS than dissatisfied patients. The only exception was the question whether the patient thought hip mobility had increased after the operation. At 7 weeks follow-up, no difference in OHS was found between those patientsy who experienced better mobility and those who did not. One possible explanation is that after such a short follow-up, a less mobile hip joint may not infiuence daily life as much as it might in the long run.

The OHS showed an improvement with time. The largest change was seen in the first year, and the score reached a plateau after the first year of follow-up. This trend was also seen with the general questions for improved hip function and decreased pain. Longer follow-up will be necessary to determine how the score develops after two years. The fact that the mean total score has neither its maximal nor its minimal value is a psychometric advantage: it leaves room for developments in both positive and negative directions. Ceiling and floor effects are prevented. Compared with the RAND36, the OHS was more sensitive to alterations in time. This is to be expected, since the RAND-36 is a generic tool (Wright and Young Citation1977).

The reproducibility and the validity of the OHS matched those of the original 12-item questionnaire. This is important when research results measured with the OHS are compared with those measured with the original 12-item questionnaire. Our investigation has proven that the OHS is a useful instrument to judge the result of a total hip arthroplasty from the patient's point of view. By using the original questionnaire and interpretation of the results, McMurray et al. (Citation1999) stated that the use of walking aids, the use of medication and comorbidity could cause distortion of the actual situation. It appears to be difficult for the patient to imagine the situation without walking aids, medication or comorbidity. This phenomenon can also be seen in our population. The patients in Charnley class C had a significantly worse mean OHS than the patiens in class A or B. Therefore, the answers to the activity questions should not be interpreted as the absolute capability, but rather the relative capability of the patient. Since this is a problem associated with the validity of almost all disease-specific questionnaires, it is an item that should be evaluated more thoroughly.

The use of the OHS has many advantages. Firstly, it is advantageous for the patient since specific problems can be evaluated. Secondly, it will be of benefit to the surgeon, since the questionnaire can be used as a guide in interacting with the patient. Thirdly, it makes repeated assessment easier, since the questionnaire can be sent and returned by mail. Finally, it should be borne in mind that the OHS is meant to be used in combination and as material that is supplementary to the evaluation by the surgeon. It is not meant to be a substitute. The combination of opinions of the patient and the surgeon will give a fair evaluation of a total hip replacement.

No competing interests declared.

- Bland J M, Altman D G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1996;; 8: 307–10

- Bland J M, Altman D G. Measurement error. BMJ 1996; 312: 1654

- Britton A R, Murray D W, Bulstrode C J, McPherson K, Denham R A. Pain levels after total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1997; 79(1)93–8

- Carlsson A M. Assessment of chronic pain. Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analog scale. Pain 1983; 16: 87–101

- Charnley J. The long-term results of low-friction arthroplasty of the hip performed as a primary intervention. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1972; 54: 61–7

- Cronbach L J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951; 16(3)297–334

- Currey H L F. Osteoarthritis of the hip and sexual activity. Ann Rheum Dis 1997; 29: 488–93

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A, Murray D. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996a; 78: 185–90

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A. The problem of “noise” in monitoring patient-based outcomes: generic, disease-specific and site-specific instruments for total hip replacement. J Health Serv Res Policy 1996b; 4: 224–31

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A. Comparison of measures to assess outcomes in total hip replacement surgery. Qual Health Care 1996c; 5: 81–8

- Fitzpatrick R, Dawson J. Health-related quality of life and the assessment of outcomes of total hip replacement surgery. Psychol Health 1997; 12: 793–803

- Fitzpatrick R, Morris R, Hajat S, Reeves B, Murray D W, Hannen D, Rigge M, Williams O, Gregg P. The value of short and simple measures to assess outcomes for patients of total hip replacement surgery. Qual Health Care 2000; 9: 146–50

- Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993; 46(12)1417–32

- Guyatt G H. The philosophy of health related quality of life translation. Qual Life Res 1993; 2(6)461–5

- Harris W H. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures; treatment by mold arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1969; 51: 737–55

- Johnston R C, Moines D, Fitzgerald R H, Harris W H, Poss R, Muller M, Sledge C B. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1990; 72(2)161–8

- Kazis L E, Anderson J J, Meenam R F. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care 1989; 27(Suppl)178–89

- Liang M H, Cullen K E, Poss R. Primary total joint replacement: evaluation of patients. Ann Intern Med 1982; 97: 735–9

- Lieberman J R, Dorey F, Shekelle P, Schumacher L, Thomas B, Kilgius D, Finerman G A. Differences between patients' and physicians' evaluations of outcome after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1996;; 78(6)835–8

- Mc Graw K O, Wong S P. Forming is references about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psych Methods 1996; 1: 30–46

- McMurray R, Heaton J, Sloper P, Nettleton S. Measurement of patient perceptions of pain and disability inrelation to total hip replacement: the place of the Oxford Hip Score in mixed methods. Qual Health Care 1999; 8: 229–33

- Merle d'Aubigné R M, Postel M. Functional results of hip arthroplasty with acrylic prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1954; 36: 451–75

- Stern S H, Fuchs M D, Ganz S B, Classi P, Sculco T, Salvati E. Sexual function after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1991, 269: 228–35

- Van der Zee K, Sanderman R. RAND-36 een handleiding. Noordelijk Centrum voor Gezondheids vraagstukken. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen 1993

- Van der Zee K, Sanderman R, Heyink J. Psychometrische kwaliteit van de MOS 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) in een Nederlandse populatie. Tijdschr Soc Gezondheidsr 1993; 71: 183–91

- Wright J G, Young N L. A comparison of different indices of responsiveness. J Clin Epidemiol 1977; 50: 239–46

- Wright J G, Rudicel S, Feinstein A R. Ask patients what they want: evaluation of individual complaints before total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1994; 76: 229–35