Abstract

Background By arthroscopy, we observed a phenomenon that, according to our knowledge not previously described, we call the "biceps tendon footprint" (BTF)-an area of chondromalacia beside the bicipital groove.

Patients and methods We studied 118 shoulder arthroscopies prospectively. We documented whether a BTF could be observed and what the main pathology associated with it was. We used 3 grades of cartilage wear to describe BTF, and we analyzed pathological changes in associated structures (subscapularis, biceps tendon and humeral head).

Results We found a BTF in 16% of the cases. Associated diagnoses were cuff tears and instabilities, most often multidirectional. We observed all 3 grades of cartilage wear, grade 3 being the commonest. Biceps synovitis occurred more often in the BTF group.

Interpretation BTF is not a rare phenomenon. Mal-traction of the intraarticular biceps tendon in MDI and cuff tears in addition with biceps synovitis appear to cause BTF.

There is a vast amount of literature dealing with the anatomy, mechanics and pathology of the long head of the biceps tendon. We could not find a description of a phenomenon that we had observed several times by arthroscopy. By analogy with the "footprint" of the rotator cuff (Tierney et al. Citation1999, Ruotolo et al. Citation2004), we call it the "biceps tendon footprint" (BTF). Contrary to the rotator cuff footprint, BTF is a pathological finding. It is an area of chondromalacia or-depending on the grade of cartilage wear-bare bone beside the bicipital groove. We believe that this chondromalacia is caused by the long head of the biceps tendon. In reviewing several books on shoulder diseases (Snyder Citation2003, Rockwood and Matsen Citation2004) or shoulder arthroscopy (Snyder Citation2003, Tibone et al. Citation2003), and also the the original literature (Habermeyer et al. Citation1998, Favorito et al. Citation2001, Ruotolo et al. Citation2002, Barthel et al. Citation2003) we could not find any information about this phenomenon. We therefore started a prospective trial to obtain information on how often it appears, to what pathologies it might be associated, and whether there are different types of BTF-so that a grading might be possible.

Patients and methods

Between January 2003 and March 2004, we performed 118 shoulder arthroscopies in 118 patients (). The arthroscopies were performed on 62 men and 56 women and in 71 right and 47 left shoulders, and all were done by the same surgeon. The average age was 52 years. The arthroscopy was routinely performed using a standard posterior portal and an anterior portal for visualization and placing of the instruments. We used the 15-point technique of Snyder (Citation2003) to evaluate the shoulder joint.

Table 1. Indications for shoulder arthroscopy (main intraarticular pathology)

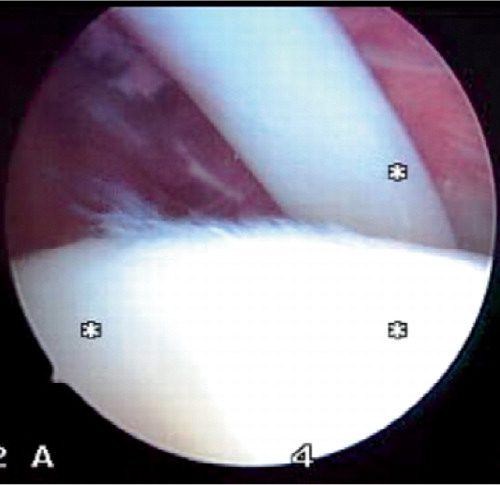

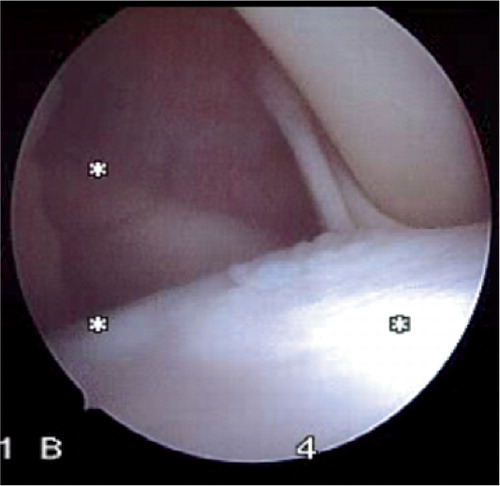

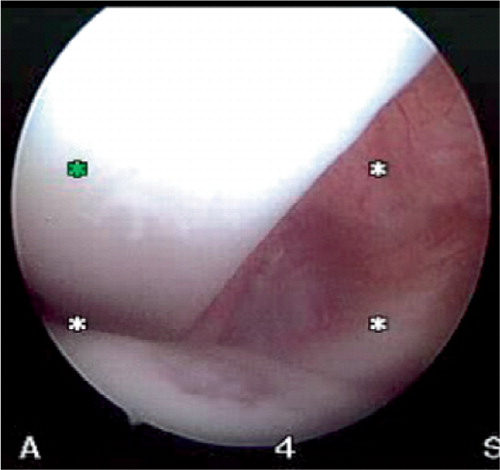

In this prospective study, we documented the occurrence of BTF and the grade of cartilage wear (Figure). We used the Ogilvie-Harris classification (Ogilvie-Harris and Jackson Citation1984) to categorize the degree of cartilage wear. BTF is classified as grade 1 when a smoothing of the cartilage is apparent, but when it does not affect the subchondral bone. In grade 2 there is fraying of the cartilage and broken cartilage surface present. In grade 3 there is more cartilage wear, with exposure of bare bone.

We also recorded pathological changes at the subscapularis tendon (partial or complete tear) (Gerber and Sebesta Citation2000, Bennett 2001b) or of the intraarticular portion of the long head of the biceps tendon (synovitis, fraying/partial/complete tear, subluxation/dislocation) (Bennett 2001b, Werner et al. 2003). The main diagnosis of associated shoulder disease was documented.

For statistical analysis, we used the Mann-Whit-ney U Test.

Results ()

We observed a BTF in 19 of 118 patients (16%). It occurred in 12 men and 7 women. In 12 cases, the right side was affected; in 7, the left shoulder was affected. 4 patients had grade 1 cartilage wear, 10 had grade 2 and 5 had grade 3 wear. A rotator cuff tear was the main diagnosis in 9 of 19 patients in the BTF group and was found in 11 of 99 shoulders in the non-BTF group (p = 0.001). Instability was observed in 4 of 19 shoulders in the BTF group and in 4 of 99 shoulders in the non-BTF patients (p = 0.02). There was 1 instability patient with a typical anterior inferior dislocation, and 3 with a multidirectional instability.

Table 2. Associated intraarticular pathologies in BTF and non-BTF group

The other main diagnoses in the BTF group were: 1 SLAP 2 lesion, 2 cases of shoulder stiffness, 1 case of infection and 2 situations that were unclear. In the non-BTF group, 3 cases of shoulder stiffness were diagnosed. The long head of the biceps tendon (LBT) was dislocated in 4 patients in the BFT group, and 2 patients in the non-BTF group showed a dislocation. We found a synovitis at the intraarticular portion of the biceps tendon in 11 patients with BTF and in 28 with non-BTF (p = 0.02). A complete tear of the LBT occurred in 1 BTF patient and in 8 non-BTF patients. A partial LBT tear was seen in 1 BTF and 10 non-BTF arthroscopies.

We observed no pathology of the intraarticular portion of the subscapularis muscle in the BTF patients, but in 4 non-BTF patients we could see a partial (1) or complete subscapularis tear (3).

Discussion

We found that BTF was associated with rotator cuff tears (Bennett 2001a) and shoulder instabilities. The average age of 52 years demonstrates that we mainly operated on degenerative shoulder diseases. Analyzing the subgroups of cuff tears and instability was not meaningful, because of the small numbers of patients in each of these groups. The type or size of cuff tear gave no additional information. In the instability patients, it is obvious that there was a tendency towards multidirectional instability.

According to the Ogilvie-Harris classification (Ogilvie-Harris and Jackson Citation1984), grade 2 cartilage wear was by far the most common. By describing the grade of cartilage wear, it is possible to distinguish different types of BTF-which may help to describe BTF more precisely in further studies and help to assess whether it is a dynamic phenomenon, developing from grades 1-3 over several years.

The presence of subscapularis pathology does not seem to be important for the development of BTF. We found no subscapularis involvement in the BTF group, which shows that anterosuperior impingement with the arm in flexion and internal rotation does not appear to be of importance for the development of BTF. The cause of BTF is unclear. We believe that a cuff tear or predominantly multidirectional instability may cause a maltracking of the intraarticular portion of the long head of the biceps tendon, leading to cartilage wear. A complete dislocation, as described by Petersson (Citation1983), does not appear to be the main cause.

The higher synovitis rate that we found in BTF patients may be caused by maltracking of the biceps tendon. Some authors (De Palma and Callery Citation1954) believe that tendosynovitis is the main cause of maltracking. From our data, we cannot say whether synovitis is the first pathological change and leads to BTF in the end, or vice versa. Another possible cause that could contribute to the development of BTF might be a variation of the bicipital groove, which is unique in humans (Hitchcock Citation1948). We could not see any osteophytes/spurs in or at the bicipital groove during arthroscopy of our cases with BTF (Hitchcock and Bechtol Citation1948).

Complete dislocation of the LBT is seen more often in BTF patients, but we did not do statistical analysis because the number of subjects was too low in both groups (4 in BTF and 2 in non-BTF). In our opinion, a complete dislocation is not always necessary to cause a BTF. It seems that most of the BTFs occur due to a maltracking of the LBT. We consider that a maltracking seems to be the most likely mechanism for the development of BTF. We do not know whether BTF could cause degeneration of the long head of the biceps tendon. It is possible that it starts with grade 1 cartilage wear, which increases to stage 3 or a groove-the borders of which function like osteophytes, coming in conflict with the tendon and wearing the tendon off.

In summary, recognition of BTF during shoulder arthroscopy may indicate the presence of multidirectional instability or a cuff tear, or long biceps tendon maltracking. However, for the diagnosis of these conditions one cannot rely on BTF alone. Preoperative history, clinical examination and assessment are more important.

- Barthel T, Konig U, Bohm D, Loehr J F, Gohlke F. Anatomy wof the glenoid labrum Orthopade. 2003; 32(7)578–85

- Bennett W F. Subscapularis, medial, and lateral head coracohumeral ligament insertion anatomy. Arthroscopic appearance and incidence of "hidden" rotator interval lesions. Arthroscopy 2001a; 17(2)173–80

- Bennett W F. Visualization of the anatomy of the rotator interval and bicipital sheath. Arthroscopy 2001b; 17(1)107–11

- De Palma A F, Callery G E. Bicipital tenosynovitis. Clin Orthop 1954; 3: 69–85

- Favorito P J, Harding, 3rd, W G, Heid R S. Complete arthroscopic examination of the long head of the biceps tendon. Arthroscopy 2001; 17(4)430–2

- Gerber C, Sebesta A. Impingement of the deep surface of the subscapularis tendon and the reflection pulley on the anterosuperior glenoid rim: a preliminary report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2000; 9(6)483–90

- Habermeyer P, Ebert T, Jung D. Current status of shoulder arthroscopy. Ther Umsch 1998; 55(3)175–83

- Hitchcock H H, Bechtol C O. Painful shoulder. Observations on the role of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii in its causation. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1948; 30: 263–73

- Ogilvie-Harris D J, Jackson R W. The arthroscopic treatment of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1984; 66(5)660–5

- Petersson C J. Degeneration of the gleno-humeral joint. An anatomical study. Acta Orthop Scand 1983; 54(2)277–83

- Rockwood C A, Matsen F A. The Shoulder. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia 2004

- Ruotolo C, Nottage W M, Flatow E L, Gross R M, Fanton G S. Controversial topics in shoulder arthroscopy. Arthroscopy 2004; 20(3)246–9, (Suppl 1)

- Ruotolo C, Fow J, E, Nottage W M. The supraspinatus footprint: an anatomic study of the supraspinatus insertion. Arthroscopy 2004; 20(3)246–249

- Snyder S J. Shoulder. Shoulder Arthroscopy. Springer, New York 2003

- Tibone J E, Shaffer B, S, Savoie F H, Davis Ch S, McCarthy J C. The footprint of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy.

- Tierney J, Curtis A, S, Scheller A D. Tendinitis of the long head of biceps tendon associated with lesions of the “biceps reflection pulley. Annual AAOS Meeting 1999, Paper #281.

- Werner A, Ilg A, Schmitz H, Gohlke F. Tendinitis of the long head of biceps tendon associated with lesions of the ”biceps reflection pulley. Sportverletz Sportschaden 2003; 17 2: 75–9