Abstract

Background Statistically significant differences between treatments (i.e., results typically associated with p < 0.05) may not always correspond to important differences upon which to base orthopedic practice. If the hypothesis that p < 0.05 unduly influences the perception of importance of study results were true, we would expect that presenting such a p-value would lead to 1) greater agreement among clinicians about the importance of a study result, and 2) greater perceived importance of a study result, when compared with presenting the same results omitting the p-value.

Methods The participants were 3 orthopedics residents, 5 fellows, and 4 attending orthopedic surgeons at a university hospital. We constructed a 40-item questionnaire with the comparison groups, primary outcome of interest, and the results from each of 40 studies. These studies represent a variety of interventions across orthopedic surgery assessed in 2-group comparative intervention studies (randomized trials, observational studies) and were published between 2000 and 2002 in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American Volume. For each question, respondents were asked to rate the importance of the study results. Participants answered the questionnaire first without p-values and then, 8 weeks later, with p-values (and a random sample of items without p-values). An intra-class correlation quantified agreement between clinicians when answering items with and without p-values. The difference in mean importance scores between the two presentations was also estimated.

Results Of 40 eligible clinical comparative studies, 30 reported p < 0.05 for their primary comparison. Without presenting p-values, overall agreement regarding clinical significance among reviewers was fair (ICC = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.25–0.49). In the 30 studies with p < 0.05, mean importance scores (1 = low; 3 = high) were greater when p-values were presented (difference 0.6, CI 0.1–1.1). 10 of 12 reviewers perceived results to be more important when presented with significant p-values.

Interpretation When significant, p-values unduly influence the perception of clinicians regarding the importance of study results.

Evidence-based medicine is gaining wide acceptance in orthopedics (Narayanan and Wright Citation2002, Bhandari and Tornetta Citation2003, Wright et al. Citation2003). However, there remains a misconception that treatments leading to a statistically significant improvement (p < 0.05) produce improvements that are important to the patient, i.e. statistical significance is equated to clinical significance (Guyatt et al. Citation2003, Wright et al. Citation2003). Relying solely on p-values can be misleading (Luus et al. Citation1989, Nurminen Citation1997, Shakespeare et al. Citation2001, Sterne and Davey Smith Citation2001). Since R.A Fisher's original idea of significance testing (Fisher Citation1973), the use and interpretation of p-values in the medical literature has remained controversial. P-values tell us very little about the size and direction of a treatment effect, or the range of plausible values consistent with the data (i.e. confidence intervals).

Importantly, p-values do not inform surgeons and patients about the importance of treatment effects. A significant p-value (p < 0.05) can result from clinically irrelevant treatments effects, whereas a non-significant result (p < 0.05) could mask a potentially important finding limited by a type II or beta error (Lochner et al. Citation2001, Bernstein et al. Citation2003). Most readers would agree that trials requiring 25 000 patients to detect a 0.5% difference in the risk of an undesirable outcome between two treatments, although statistically significant, may not represent a clinically important difference. Similarly, readers may argue that a trial of 30 patients that reveals a 50% difference in the risk of serious complications—despite a non-significant p-value—may represent a clinically important difference. Unfortunately, most published reports fall within these two extremes.

Current guidelines in major orthopedics journals such as the the Journal of Bone and Joint (Am) require authors to report p-values when claims regarding “significance” are made. However, in an attempt to lessen the emphasis on p-values, journals such as the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Am), Acta Orthopaedica, and Canadian Journal of Surgery now require the presentation of confidence intervals around a point estimate of effect.

The influence of publishing p-values on perceptions of the importance of study results remains largely unknown. We hypothesized that a p-value of < 0.05 unduly influences clinicians’perception of the importance of study results. If this hypothesis were true, we would expect that presenting such a p-value would lead to: 1) greater agreement among clinicians about the importance of a study result, and 2) greater perceived importance of a study result, when compared with presenting the same results omitting the p-value. We tested this hypothesis by assessing reviewers’perceptions of the importance of study results in the same studies presented with and without p-values at two different time points.

Methods

The participants were 3 surgical trainees in orthopedics, 5 fellows in orthopedics, and 4 attending orthopedic surgeons at one university hospital (St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto). The reviewers were those rotating at the university hospital for at least one consecutive 3-month period. 1 resident and 2 orthopedic surgeons, who were otherwise eligible, chose not to participate in the study.

We conducted a database search (PubMed) and manual search of all comparative clinical studies of therapy (randomized trials, prospective cohorts, case controls) in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Am) from 2000–2002. From 310 studies reviewed, we identified 90 comparative studies. From these, a purposeful sample of 40 studies was selected to represent a variety of interventions across orthopedic surgery. Eligible studies had two comparison groups.

We constructed a 40-item questionnaire with the comparison groups, primary outcome of interest, and the results from each of the 40 studies. (The full questionnaire is available from authors on request). For each study, we identified the primary outcome (or the first outcome presented in the results section if a primary outcome was not clearly labeled). The studies were numbered randomly from 1 to 40. For each, we presented the proportion of outcome events (%) or the mean values (for continuous variables) for both comparison groups. No other statistical measures were presented. The authors, institutions, and design of each study (randomized trial, observational study) were also omitted. A second questionnaire was developed using the same 40 studies—randomly ordered, but with the addition of p-values for the difference in primary outcomes between treatments. The second questionnaire also contained a sample (n = 10) of exactly the same studies from the first questionnaire, without p-values. Participants answered the two questionnaires 8 weeks apart. To limit responses based on direct recognition of questions from the original review, we varied the order of questions on a random basis, and included a small sample of new questions which were not used in reliability calculations.

For each question, respondents were asked to rate the clinical importance of the results using a 5-point Likert-type scale based on the following anchors: definitely not a clinically important difference, probably not a clinically important difference, unsure, probably a clinically important difference, and definitely a clinically important difference.

We used intra-class correlation coefficients to quantify both intra- and inter-observer agreement among reviewers for the importance ratings with and without p-values. We used the approach of Landis and Koch (Citation1977) in our interpretation of inter-reviewer agreement: ICCs from 0 to 0.2 represent slight agreement, 0.21 to 0.40 fair agreement, 0.41 to 0.60 moderate agreement, 0.61 to 0.80 substantial agreement, and < 0.80 near perfect agreement.

We averaged the clinical importance ratings for each reviewer across all studies, collapsing the importance scale from 5 points to 3 (1 = definitely/probably unimportant, 2 = unsure, and 3 definitely/probably important). This mean rating represented the overall direction of each reviewer's perceptions about the importance of study results and it permitted comparison of ratings with and without p-values.

Results

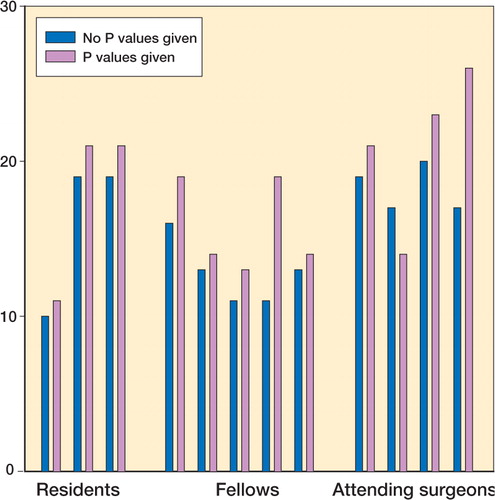

Intra-observer agreement (when testing the same reviewers with the same studies with and with-out p-values), and inter-observer agreement about the importance of study results was fair (). Presentation of p-values did not improve the inter-observer agreement about the importance of study results (difference in ICC: 0.2, 95% CI: -0.02–0.3). However, there was heterogeneity in this result: p-values improved the inter-observer agreement among participating staff surgeons and fellows, but not among participating residents ().

Table 1. Agreement within reviewers in interpreting clinical importance. Values are intraclass correlation coefficient and 95% confidence interval

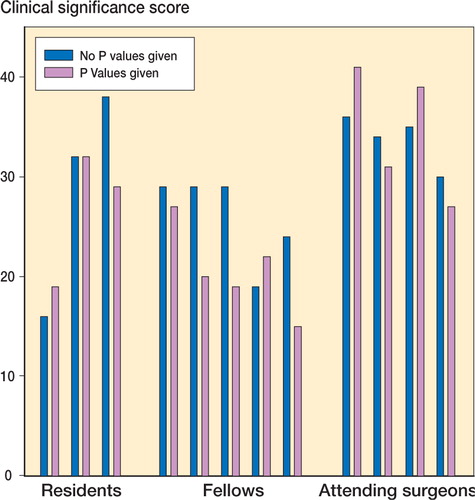

In those 30 studies with p-values of < 0.05, mean clinical importance scores were greater when p-values were provided to reviewers (). The introduction of nonsignificant p-values, however, had no influence on the importance scores ().

10 of 12 reviewers perceived the results to be more important when presented with significant p-values (). 7 of 12 reviewers perceived the results to be less important when presented with nonsignificant p-values ().

Discussion

Our study has several strengths. Eligible studies included a range of p-values and treatment effects, with both continuous and dichotomous outcome measures. We included multiple reviewers with varying levels of experience to improve the generalizability of our findings. We also retested reviewers at 8 weeks. Our decision to blind reviewers as to the authors of papers and their institutions was aimed at limiting bias associated with institutional recognition. Our findings, however, cannot be generalized beyond the academic setting and the individuals who took part in it. Our small sample of reviewers further limits the generalizability of our conclusions. We consider that our analyses involving residents, fellows and staff surgeons—although preliminary—can assist in generating further hypotheses.

Our findings suggest that significant p-values unduly influence reviewers’perceptions of the importance of study results. A more informative alternative to p-values is the reporting of confidence intervals. Conventionally defined, the 95% confidence interval assumes that if a study were conducted 100 times, the confidence interval would include the true value 95 times (Shakespeare et al. 2001, Sterne et al. 2001). Another approach (the Bayesian approach) defines the 95% confidence interval as having a 95% probability of containing the true estimate of effect. The confidence interval overcomes the limitations of the p-value by providing information about the size and direction of the effect, and the range of values for the treatment effect that remain consistent with the observed data. Unfortunately, our search of the ‘instructions to authors'sections of several general orthopedics journals found only two journals that advocated reporting of confidence intervals (the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Am) and Acta Orthopaedica). Journals with no reported statements on significance tests included the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-British volume, Clinical Orthopae-dics and Related Research, Journal.

Although our current study has focused on clinical importance, this approach gives little attention to the values and preferences of patients. We have suggested that the emphasis should be on results that are important to the patient rather than those that are clinically important (Guyatt et al. Citation2004). This requires an understanding of what information, including data on benefits and disadvantages (risks, burden, and cost) of our interventions, patients need to make informed choices. In this context, statistical or clinical significance will be meaningless if the outcomes are not important to patients.

Ultimately, our study suggests that current reporting practices on the precision of study results which rely exclusively on p-values may hinder the ability of clinicians to judge the importance of study results. Perhaps clinicians will find the interpretation of confidence intervals more intuitive. Given that the convention of using p-values seems to impair understanding of research results, is it time to abolish their use?

We thank John Olmeida for assistance in identification of articles and administration of questionnaires. M. Bhandari was funded in part by a Detweiler Fellowship, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. V. M. Montori was a Mayo Foundation Scholar.

No competing interests declared.

- Bernstein J, McGuire K, Freedman K B. Statistical sampling hypothesis testing in orthopaedic research. Clin Orthop 2003, 413: 55–62

- Bhandari M, Tornetta III P. Evidence-based orthopaedics: a paradigm shift. Clin Orthop 2003, 413: 9–10

- Fisher R A. Statistical methods and scientific inference. Collins Macmillan, London 1973

- Guyatt G H, Montori V, Devereaux P J, Schunemann H, Bhandari M. Patients at the center: In our practice, and in our use of language. ACP J Club 2004; 140: A11

- Landis J R, Koch G G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33: 159–74

- Lochner H, Bhandari M, Tornetta P. Type II error rates (beta errrors) in randomized trials in orthopaedic trauma. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2001; 83: 1650–5

- Luus H G, Muller F O, Meyer B H. Statistical significance versus clinical relevance. Part II. The use and interpretation of Confidence intervals. S Afr Med J 1989; 76: 626–9

- Narayanan U G, Wright J G. Evidence-based medicine: a prescription to change the culture of pediatric orthopaedics. J Pediatr Orthop 2002; 22: 277–8

- Nurminen M. Statistical significance. A misconstrued notion in medical research. Scand J Work Environ Health 1997; 23: 232–5

- Shakespeare T, Gebski V J, Simes J. Improving interpretation of clinical studies by the use of Confidence intervals, clinical significance curves, and risk-benefit contours. Lancet. 2001; 357: 1349–53

- Sterne J, Davey Smith G. Sifting the evidence. What's wrong with significance tests. BMJ 2001; 322: 226–31

- Wright J G, Swiontkowski M F, Heckman J D. Introducing levels of evidence to the journal. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003; 85: 1–3