Abstract

Background A blood transfusion is a costly transplantation of tissue that may endanger the health for the recipient. Blood transfusions are common after total hip arthroplasty. The total saving potential is substantial if the blood loss could be reduced. Studies on the use of tranexamic acid have shown interesting results, but its benefits in total hip arthroplasty have not yet been resolved.

Patients and methods 100 patients receiving a total hip arthroplasty (THA) got a single injection of tranexamic acid (15 mg/kg) or placebo intravenously before the start of the operation. The study was double-blind and randomized. Total blood loss was calculated from the hemoglobin (Hb) balance. Volume and Hb con-centration of the drainage was measured 24 h after the operation. Intraoperative blood loss was estimated volumetrically and visually.

Results The patients who received tranexamic acid (TA) bled less. The total blood loss was on average 0.97 L in the TA group and 1.3 L in the placebo group (p < 0.001). 8/47 (0.2) in the TA group were given blood transfusion versus 23/53 (0.4) in the placebo group (p = 0.009). Drainage volume and drainage Hb concentration were less in the TA group (p < 0.001 and p = 0.001). No thromboembolic complications occurred.

Interpretation Considering the cost of blood and tranexamic acid only, use of the drug would save EUR 47 Euro per patient. We recommend a preoperative single dose of tranexamic acid for standard use in THA.

Tranexamic acid decreases blood loss and transfusion need after total knee arthroplasty (Hiippala et al. Citation1995, Benoni et al. Citation1996, Good et al. Citation2003). Concerning total hip arthroplasty (THA), there is less evidence for such benefits in total hip replacement (THR). 4 studies have indicated lower blood loss, but only Husted et al. have shown a decrease in the need for transfusion (Ekbäck et al. Citation2000, Ido et al. Citation2000, Benoni et al. Citation2001, Husted et al. Citation2003). With the exception of Benoni et al. (Citation2001), a continuous infusion or a second bolus dose followed the preoperative bolus dose.

The timing of administration of tranexamic acid seems to be crucial. When given at the end of the operation, it is of little or no use (Benoni et al. Citation2000). To study a simple regimen, we chose to evaluate the effects of a single bolus dose of tranexamic acid, given intravenously immediately before surgery, on different aspects of blood loss and the need for blood transfusion.

Patients and methods

Study design

The study was conducted between September 2002 and December 2003, and was approved by the regional ethics committee (Dec 11, 2001 Registration no. 01-438). The study involved two hospitals (Linköping University Hospital and Kalmar Hospital), and 119 patients were included after informed and written consent had been obtained. Inclusion criteria were: planned THA due to osteoarthrosis, no history or laboratory signs of bleeding disorders (activated partial thrombin, prothrombin time, and thrombocyte count within standard limits), absence of malignancy and rheumatic joint disease, no consumption of aspirin or NSAIDs within a week before surgery, no history of coagulopathy or thrombembolic events and plasma creatinine levels below 115 μmol/L in men and 100 μmol/L in women.

Coded ampoules containing either tranexamic acid (TA) (100 mg/mL Cyklokapron; Pharmacia) or saline as placebo were prepared by Apoteksbolaget, Umeå, Sweden. The contents of the ampoules were randomized by a computer in blocks of 10 (5 TA, 5 saline). Immediately before the start of the operation, the patients received a bolus infusion of TA (15 mg/kg) mixed in 100 mL normal saline, or the same volume of placebo. All personnel and patients were blinded as to the treatment until the randomization code was broken, which took place after all patients had been evaluated. According to the study plan, the goal was to include 100 patients. During the study, we became aware that it would not be possible to evaluate some of the patients (see below). Thus, we kept on randomizing patients until we ran out of ampoules (100 plus 20 ampoules in reserve, of which one broke, allowing us to enter 119 patients into the study).

Before the randomization code was broken, 19 patients were excluded due to violation of the study plan: 11 patients had not received drains or the drains were removed too early, 6 had been given drugs that could have influenced the blood loss, important data was missing for one patient, and 1 patient had been operated bilaterally. Thus, 100 patients could be analyzed, 47 of whom had received TA and 53 of whom had received placebo.

Patients

The patient characteristics are given in .

Table 1. Patient characteristics

Perioperative and surgical procedures

All patients were operated with spinal anesthesia (17.5–20 mg Marcain Spinal; AstraZeneca). For thrombosis prophylaxis, dalteparin (Fragmin; Pharmacia) was injected subcutaneously: 2,500 IU twice on the day of surgery, and 5,000 IU daily thereafter until full mobilization. The surgeons were unselected staff members and 23 individuals performed the operations (1–16 operations each). A dorsolateral approach was used. The patients received cemented stems and cups (Lubinus SP II; Link, Hamburg, Germany). A subfascial drain was used in all patients.

The guideline threshold for blood transfusion was an Hb level of 90 g/L, with consideration of clinical well-being. Allogeneic leucodepleted red blood cell concentrate (RBCC) was given, in 250-mL units containing about 150 mL cells and 10–20 mL plasma. Pre-donated autologous blood was not used.

Calculation of blood loss

Intraoperative blood loss was estimated (by the nurse anesthetist) as the blood remaining in sponges and drapes and the volume in suction bottles. Total blood loss was based on the Hb balance method. We assumed that the blood volume (BV, mL) was normalized on the fifth postoperative day. BV was estimated according to Nadler et al., taking sex, body mass and height into account (Nadler et al. Citation1962). The extravasation of Hb (g) was calculated according to the formula:

Hb loss = (Hbpre − Hbe) × BV + Hbt

The drains were removed 24h postoperatively and Hb content of the drain bag was determined.

Subjective appraisal of the treatment given

At the end of the operation, the nurse anesthetist had to state whether she or he thought the patient had received TA or placebo. Thereafter, and separately, the surgeon was asked the same question.

Follow-up

All patients were contacted after 6–8 weeks and asked about postoperative complications, in particular wound complications and thrombembolic events.

Statistics and ethical considerations

A power analysis based on previous data (Johansson etal. Citation1999) showed that a clinically relevant reduction in total bloodl oss (450 mL), with 90% power (alpha 0.05), would require atleast 43 patients in each group. Data are expressed as mean (SD). Student's t-test was used for parametric data. The chi-square test was used for categorical values. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. The trial was performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Results

Clinical results

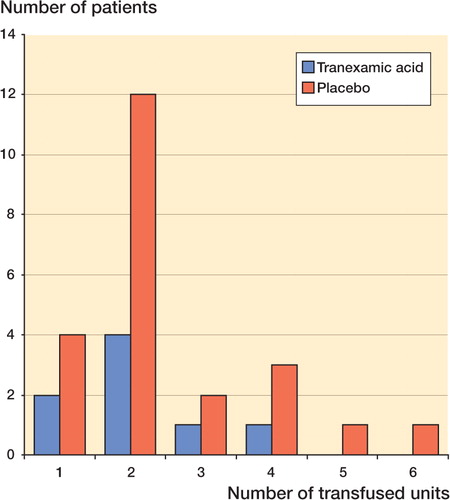

All comparisons regarding blood loss were numerically positive in favor of tranexamic acid. The total blood loss was reduced by 27% (95% CI: 12–42) (). In the TA group, 8 of 47 patients (0.2) received transfusions, as compared with 23 of 53 (0.4) in the placebo group. The average number of transfusions per patient in the tranexamic acid group was reduced by two-thirds compared with the placebo group: 0.36 and 1 units, respectively ().

Table 2. Blood loss and transfusions

Figure Number of patients receiving 1–6 units of blood transfusion (tranexamic acid: n = 47; placebo: n = 53). Patients in the tranexamic acid group received fewer units than those in the placebo group.

The nurse anesthetists and the surgeons were unable to tell whether the patients had received TA or placebo (). At follow-up after 6 weeks, no patient had been treated for thrombembolic events. 3 patients had been examined with ultrasound under suspicion of leg thrombosis, but all investigations were negative. Superficial wound infections were seen in 2 patients in the placebo group, but healed uneventfully after antibiotic treatment.

Table 3. Comparison of guesswork by nurses and surgeons with actual breakdown of treatment

Cost-effectiveness analysis

In this study, 4/5 patients weighed more than 67 kg and would have needed 2 ampoules of TA, since 1 ampoule contains 1,000 mg. If all patients had received TA 15 mg/kg, the average cost would have been (180 ampoules × EUR 5)/ 100 patients = EUR 9 per patient.

At our hospitals, the cost for 1 unit of blood is EUR 78. The cost saving for transfusions when tranexamic acid is used would be: EUR 78/unit × reduction in average transfusion (1.08 – 0.36 units) = EUR 56. Thus, if the results from this study were generalized, the cost saving would be EUR 56 – EUR 9 = EUR 47 per patient.

Discussion

TA decreased the calculated total blood loss by 27%. This study is the only one that has shown a decrease in the number of transfused patients after a THR. Several other blood-saving methods can be used in THR. Pre-donation of autologous blood, with or without erythropoietin treatment, can be performed if the procedure is elective. Intraoperative normovolemic hemodilution, controlled hypotension and intra- and postoperative autologous transfusion can be used in connection with surgery. Even though blood saving can be achieved by such methods, nearly all of them entail increased costs—some of them distinctly so—in addition to logistic problems (pre-donation, erythropoietin). Some methods are technically demanding (intra-operative hemodilution, controlled hypotension) and not without risk; intraoperative autotransfusion requires costly equipment, and a technician may be needed during the procedure. As illustrated by our data and those of others (Umlas et al. Citation1994), the yield of erythrocytes from postoperative autotransfusion (retransfusion of drainage) is low. In our study, the 24-h drainage accounted for about 20% of the total blood loss. For practical reasons, far less would be available for retransfusion.

When we planned our study, we wanted to develop a simple clinical routine. We found that a single preoperative bolus dose was sufficient to reduce blood loss and also the need for transfusion. We doubt, but cannot rule out, that a repeated bolus dose or a continuous infusion would have improved the results. The study was not designed to answer that question, however. It is difficult to measure blood loss. We calculated the total blood loss from Hb balance. This method would include all losses from the circulation including the “hidden loss” such as hematomas. Thigh hematomas, averaging 0.4 mL, have been shown with ultrasound after THR (Benoni et al. Citation2001).

Visual estimation of blood loss intraoperatively is imprecise. In a previous study we analyzed the hemoglobin content in swabs and suction bottles (Johansson et al. Citation1999), and in individual patients, the blood loss measured could deviate widely from the estimated loss. However, the group means agreed well between the methods. Nevertheless, our present data on intraoperative loss should be regarded with caution, and this reservation should be extended to cover calculated data on external blood loss and hidden blood loss.

The Hb concentration of wound blood may not be the same as that of circulating blood. For this reason, the weighing of swabs gives an inaccurate estimation of intraoperative blood loss. Further-more, in most studies, the drain volume has been thought to represent “blood loss”. This study and also a previous one (Johansson et al. Citation1999) have demonstrated that the drain bag content is less than 50% blood when compared with the patient's pre-operative Hb concentration. Thus, equating drain volume to blood loss is methodologically incorrect and should be abandoned.

Our observations are in agreement with those in other studies on tranexamic acid in THR. We, however, used other methods to assess blood loss than previous authors, who have mainly reported drain volume and transfusion as their end points (Ido et al. Citation2000, Benoni et al. Citation2001, Husted et al. Citation2003). Like these authors, we found a reduction in the drain volume. Interestingly, TA decreased the Hb concentration of the drainage, which again emphasizes the inadequacy of drainage volume as a measure of blood loss. Furthermore, our study has clearly shown a reduced need for transfusion with TA, which was previously only reported by Husted et al. (Citation2003). Sample size is important. All three studies mentioned here involved 40 patients, as opposed to 100 in ours.

Surprisingly, tranexamic acid seems to have few, if any, side effects. The follow-up showed no increase in thromboembolic complications, which confirms the findings in other studies on hip and knee arthroplasty. Using TA routinely, we have occasionally observed nausea if the drug is infused rapidly, and this effect is well known to the nurse anesthetists. Nevertheless, the nurses and surgeons were unable to guess whether active drug had been given. Thus, the blinding of the study was satisfactory and in most patients, immediate side effects of TA were not prominent. As the hemostatic effect of TA was mainly postoperative, the surgeons would not have perceived any difference in the “dryness of the wound”.

According to our calculations, based on costs for the drug and for banked blood only, the use of tranexamic acid would save on expenditure. To our knowledge, with the possible exception of preoperative hemodilution and hypotensive anesthesia, this is the only blood saving method that would prove positive in similar calculations. The cost saving may be even greater if other aspects of blood transfusions, such as acute transfusion reactions, transmission of infections and effects on the immune system are considered. The risks for the patients, e.g. those associated with undetected hypovolemia and anemia, must be less and may (in some patients) result in a shorter hospital stay. We believe that the use of TA may be the easiest and cheapest method of reducing blood loss after THA. The approach may not be sufficient to keep all patients transfusion-free, but it seems effective in reducing the number of patients receiving blood, as well as the total number of blood units used.

We conclude that the use of a single-dose of tranexamic acid preoperatively is a simple, safe and cost-effective method for reducing blood loss and transfusions after THR. We recommend it for use in routine THR.

Financial support for this study was obtained from the Health Research Council in the South-East of Sweden.

No competing interests declared.

- Benoni G, Fredin H. Fibrinolytic inhibition with tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomised, double-blind study of 86 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78: 434–40

- Benoni G, Lethagen S, Nilsson P, Fredin H. Tranexamic acid, given at the end of the operation, does not reduce postoperative blood loss in hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71: 250–4

- Benoni G, Fredin H, Knebel R, Nilsson P. Blood conservation with tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind study in 40 primary operations. Acta Orthop Scand 2001; 72: 442–8

- Ekbäck G, Axelsson K, Ryttberg L, Edlund B, Kjellberg J, Weckstrom J, Carlsson O, Schött U. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss in total hip replacement surgery. Anesth Analg 2000; 91: 1124–30

- Good L, Peterson E, Lisander B. Tranexamic acid decreases external blood loss but not hidden blood loss in total knee replacement. Br J Anaesth 2003; 90: 596–9

- Hiippala S, Strid L, Wennerstrand M, Arvela V, Mäntylä S, Ylinen J, Niemela H. Tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) reduces perioperative blood loss associated with total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth 1995; 74: 534–7

- Husted H, Blond L, Sonne-Holm S, Holm G, Jacobsen T W, Gebuhr P. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusions in primary total hip arthroplasty: a prospective randomized double-blind study in 40 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74: 665–9

- Ido K, Neo M, Asada Y, Kondo K, Morita T, Sakamoto T, Hayashi R, Kuriyama S. Reduction of blood loss using tranexamic acid in total knee and hip arthroplasties. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2000; 120: 518–20

- Johansson T, Lisander B, Ivarsson I. Mild hypothermia does not increase blood loss during total hip arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1999; 43: 1005–10

- Nadler S B, Hidalgo J U, Bloch T. Prediction of blood volume in normal human adults. Surgery 1962; 51: 224–32

- Umlas J, Foster R R, Dalal S A, O'Leary S M, Garcia L, Kruskall M S. Red cell loss following orthopedic surgery: the case against postoperative blood salvage. Transfusion 1994; 34: 402–6