Abstract

Background: Myringoplasty is a common procedure in otorhinolaryngology. Many techniques with different complications and outcomes have been described, one of which is hyaluronic acid fat graft myringoplasty (HAFGM). This technique, as proposed by Saliba, uses fat tissue and hyaluronic acid discs. The technique is relatively fast with a high success rate and low complications. However, what outcomes can be expected when performed by other surgeons? In this paper, we report on the technique’s success in our own hands.

Materials and methods: Based on Saliba’s protocol, we performed 86 HAFGMs by a transcanal approach between 2012 and August 2014. However, our 70% success rate was significantly different from Saliba’s 92% (p value 2.8e − 05). We visited Saliba’s clinic in order to identify critical differences between our approaches. We adapted the differences we found in our protocol and analysed another 50 HAFGMs performed afterwards, between October 2014 and December 2015.

Results: The success rate increased to 86–89%, this percentage is not different compared to Saliba’s results (p value .25 and .54).

Conclusion: HAFGM is a reproducible technique in the hands of other surgeons, but critical following of the surgical protocol is important.

Chinese abstract

背景:诱导性成形术是耳鼻喉科的常规手术。已经描述了许多具有不同并发症和结果的技术, 其中之一是透明质酸脂肪移植物鼓膜成形术(HAFGM)。 Saliba提出的这种技术使用脂肪组织和透明质酸盘。该技术相对较快, 成功率高, 并发症少。然而, 如果是其他外科医生施行这种手术, 我们可以预期什么结果呢?我们在本文报道了我们也成功地施行了该技术。

材料和方法:根据Saliba的方案, 我们在2012年至2014年8月期间通过转染方法进行了86个HAFGM手术。然而, 我们70%的成功率与Saliba的92%有显著差异(p值为2.8e-05)。我们访问了Saliba的诊所, 以确定我们的方法之间的关键差异。我们调整了我们方案中的差异, 并分析了其后在2014年10月至2015年12月之间进行的另50个HAFGM手术。

结果:成功率提高到86-89%, 这一比例与Saliba的结果没有差异(p值为0.25和.54)。

结论:HAFGM是其他外科医生可重复使用的技术, 但是必须严格遵循手术方案, 这至关重要。

Introduction

Tympanic membrane perforation is a common problem in otorhinolaryngology. Studies show that about 80% of perforations will close spontaneously [Citation1]. For persistent perforations, many surgical techniques have been described to close the tympanic membrane. Myringoplasty was already described more than 500 years ago, but after the invention of the microscope and the use of antibiotics its success rate has dramatically improved [Citation1].

The primary goal of myringoplasty is the closure of the membrane and improvement of hearing as well as prevention of recurrent middle ear infections. Closure can be achieved by foreign body materials such as Gelfoam®, basic fibroblast growth factor and Alloderm®. Autologous materials such as perichondrium, cartilage, fascia and skin are commonly used today [Citation1–6]. The success rate of closure depends on the type of graft material, surgical technique, perforation size and location of the perforation.

In 2008, Saliba first published his research and results on hyaluronic acid fat graft myringoplasty (HAFGM); 21 patients underwent surgery resulting in a closure rate of 81% [Citation6]. Technical improvements in a larger series of patients showed a 92% closure rate [Citation7]. Hyaluronic acid seems to play an important role in preventing dehydration of the perforation edges and is therefore believed to prevent fibrous tissue formation. It also stimulates acceleration and migration of epithelial cells [Citation7,Citation8]. Fat tissue is a rich source of growth factors, cytokines and stem cells and is known for good tissue regeneration properties [Citation9].

The original HAFG myringoplasty technique by Saliba is performed under local anaesthesia in an outpatient clinic. In brief, his surgical technique is as follows: after applying local anaesthesia, the edges of the perforation are de-epithelialized. About 1 cm3 of fat tissue is harvested just behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Several pieces of Gelfoam® are placed in the middle ear cavity and on top of that the fat graft is placed. One or more pieces of hyaluronic acid film are then placed on the fat graft in a way that the edges of the perforation are fully covered. Finally the hyaluronic film is covered with pieces of Gelfoam® soaked in ciprofloxacin and the ear canal is then filled with an ointment of bacitracin/polymyxin.

Based on this protocol, we performed 86 myringoplasties by a transcanal approach between 2012 and August 2014. However, our 70% success rate was significantly different from Saliba’s 92% (p value 2.8e − 05). During visits to Saliba’s clinic, we identified several differences between our approaches that may have contributed to the discrepancy in performance of the technique:

Saliba only performed surgery on ears that had no signs of infection for at least 6 months before surgery. When we corrected our data for this parameter, our success rate increased to 82%.

Saliba soaked Surgifoam® pieces with ofloxacin drops. We started first with Gelfoam® soaked in Terra-Cortril (Hydrocortisone, oxytetracycline and polymyxin B). Since steroids can impair epithelial growth, we switched to ofloxacin instead [Citation10]. Since some articles describe a slightly larger degradation time for Surgifoam® compared to Gelfoam® [Citation11], we used MeroGel®, because Surgifoam is not available in the Netherlands. This results in longer packing of the ear canal and better support of the fat graft in the middle ear. Daily application of ofloxacin drops results in a moist environment and thereby facilitates epithelial migration over the fat graft [Citation12–14].

The fat graft was harvested in the neck in the hair line, and not just behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It is important to use only fat tissue without contamination with fibrous tissue or hair follicles.

Instead of removing a full thickness ring around the edge of the perforation, Saliba only lifted the outer epithelial layer and with spoke-like movements brushed the epithelial layer away from the perforation edges. Only after instalment of the fat graft the epithelium was gently replaced.

Materials and methods

We adapted our protocol for the differences mentioned above and analysed another 50 HAFGMs performed afterward, between October 2014 and December 2015, both under general anaesthesia and local anaesthesia. presents our current modified protocol [Citation15]. In the case of tympanosclerosis, sclerotic plaque was removed.

Figure 1. Our surgery protocol in 10 steps [Citation15].

![Figure 1. Our surgery protocol in 10 steps [Citation15].](/cms/asset/3e165ed5-70aa-4979-85f7-b090a9887c5d/ioto_a_1330556_f0001_c.jpg)

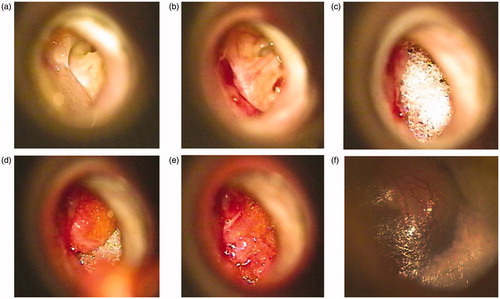

Statistical dependency was tested using the chi-square test in R 3.2.2 and Fisher’s exact test when a field had less than 10 cases. An example of our procedure is shown in the pictures below ().

Figure 2. (a) Grade III perforation just before start of surgery showing a not inflamed middle ear. (b) The epithelial layer is lifted up. (c) Several pieces of MeroGel® are placed in the middle ear cavity. (d) On top of the MeroGel®, the harvested fat graft is placed. (e) Hyaluronic acid film is placed on the fat graft. (f) 6 weeks after surgery: the tympanic membrane is closed.

Results

We performed surgery in 50 patients, 25 men and 25 women (). Most of the patients underwent general anaesthesia. In four patients, the middle ear was inflamed at the time of surgery. In , we have presented all cases as well as the results for the cases without middle ear infection. By adjusting our protocol we significantly improved the success (p value = .04) to a rate of 86%. This rate was no longer significantly different from Saliba’s performance (p value 0.25). It increased to 89% if the cases with middle ear infection were left out (compared with Saliba’s success p value 0.54). Sixty per cent of our patients were children under the age of 18 years. Seven patients were not successfully operated on, although their perforations were reduced in size. Most of the patients had a grade I (small) or II (medium) perforation [Citation6,Citation7]. Audiometry was performed before and after surgery in 42 patients. Thirty-nine patients showed an improvement of the air bone-gap with at least 10 dB ().

Table 1. Patients characteristics.

Discussion

Hyaluronic acid fat graft myringoplasty is a safe and easy way for closure of the tympanic membrane. Success rates are comparable with literature [Citation7] and since this procedure can be performed under local anaesthesia, more fragile patients can also receive this treatment.

Four of our patients had an inflamed middle ear at the time of surgery. We decided to publish the results of these four inflamed ears as well, accepting the fact that wound healing is less efficient in an inflamed environment [Citation16]. Our success rate changed from 86% to 89% when these four patients were excluded. Most of the perforations were grade I or II in size, and four of the seven patients in which the result of surgery was unsuccessful also had grade I and II perforations. In those seven patients, all perforations were reduced in size. Two of them were eventually successfully closed after a revision HAFGM procedure. Looking at the three patients where no improvement in hearing was observed we found that one patient already had no air-bone gap before surgery, and for another patient we found during surgery that the stapes footplate was fixed, which resulted in a maximal air bone-gap of 50 dB. The third patient had an inflamed middle ear.

Conclusion

HAFGM is a good and reliable surgical method in the outpatient clinic. By changing some points in our protocol we improved our success rate from 70% to 86–89% mimicking the results of Saliba. HAFGM is a reproducible technique in other surgeons’ hands, but critical following of the surgical protocol is important.

Disclosure statement

We have no conflict of interest to report and no funding was used for this research.

References

- Aggarwal R, Saeed SR, Green KJ. Myringoplasty. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:429–432.

- Dursun E, Dogru S, Gungor A, et al. Comparison of paper-patch, fat, and perichondrium myringoplasty in repair of small tympanic membrane perforations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:353–356.

- Niklasson A, Tano K. The Gelfoam® plug: an alternative treatment for small eardrum perforations. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:782–784.

- Haksever M, Akduman D, Solmaz F, et al. Inlay butterfly cartilage tympanoplasty in the treatment of dry central perforated chronic otitis media as an effective and time-saving procedure. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272:867–872.

- Hakuba N, Taniguchi M, Shimizu Y, et al. A new method for closing tympanic membrane perforations using basic fibroblast growth factor. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1352–1355.

- Saliba I. Hyaluronic acid fat graft myringoplasty: how we do it. Clin Otolaryngol. 2008;33:610–614.

- Saliba I, Woods O. Hyaluronic acid fat graft myringoplasty: a minimally invasive technique. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:375–380.

- Inoue M, Katakami C. The effect of hyaluronic acid on corneal epithelial cell proliferation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:2313–2315.

- Fraser JK, Wulur I, Alfonso Z, et al. Fat tissue: an underappreciated source of stem cells for biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:150–154.

- Jung Jung S, Fehr S, Harder-d'Heureuse J, et al. Corticosteroids impair intestinal epithelial wound repair mechanisms in vitro. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:963–970.

- Barbolt TA, Odin M, Léger M, et al. Pre-clinical subdural tissue reaction and absorption study of absorbable hemostatic devices. Neurol Res. 2001;23:537–542.

- Junker JP, Caterson EJ, Eriksson E. The microenvironment of wound healing. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:12–16.

- Mosti G. Wound care in venous ulcers. Phlebology 2013;1:79–85.

- Junker JP, Kamel RA, Caterson EJ, et al. Clinical impact upon wound healing and inflammation in moist, wet, and dry environments. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2013;2:348–356.

- Kruyt JM. Handout from presentation: Revised perspective in care for hearingloss. Rotterdam: De Kunsthal; 2016.

- Rosique RG, Rosique MJ, Farina Junior JA. Curbing inflammation in skin wound healing: a review. Int J Inflam. 2015;2015:316235.