Abstract

Background: In Sweden, an estimated prevalence of adult patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss is 0.2%, which corresponds to roughly 20,000. We know little about the use of cochlear implants (CIs) in this population and why not most of them are not offered CI.

Objectives: To investigate the reasons for no rehabilitation with CI among this patient group.

Materials and methods: Data were collected from 1076 patients in the Swedish Quality Register of Otorhinolaryngology. A baseline questionnaire and the reason for no CI, was evaluated.

Results: Only 14.5% of the patients started a CI investigation, and 8.5% were rehabilitated with CI. Significantly more women (56.5%) than men received CI. The most common reasons for not receiving CI, were hearing reason (30.5%), indicating satisfaction with technical equipment, and unknown reason (25%). The oldest patient group (81–100 years old) had the highest risk for unknown reasons. Patients receiving extended audiological rehabilitation (53.5%) had a significantly lower risk for unknown reasons.

Conclusions: It is worrying that the oldest patient group (81–100 years old) seemed to have fewer chances to start a CI investigation. An extended audiological rehabilitation increased the chances that professionals would discuss CI.

Significance: This study shows that surprisingly few patients are offered CI despite their severe-to-profound hearing loss.

Chinese abstract

背景:在瑞典, 严重至极度听力损失的成人患者的患病率估计为0.2%, 相当于约20000人。我们对这一人群人工耳蜗(CIs)的使用知之甚少, 也不清楚为何没有为他们大多数人提供人工耳蜗。

目的:探讨该类患者未进行CI康复的原因。

材料和方法:收集瑞典耳鼻喉科质量登记处的1076名患者的数据。进行了基线问卷调查并对不用CI的原因进行了评估。

结果:只有14.5%的患者开始了解CI, 8.5%的患者使用CI进行康复。接受CI的女性(56.5%)明显多于男性。不接受CI的最常见原因是听力原因(30.5%), 它是对技术设备满意度的指标。还有就是未知原因(25%)。年龄最大的患者组(81-100岁)多为未知原因。接受延长听力康复治疗的患者(53.5%)的未知原因的风险显著降低。

结论:令人担忧的是, 年龄最大的患者群体(81-100岁)开始了解CI的机会似乎更少。延长听力康复期增加了专业人员讨论CI的机会。

意义:这项研究表明, 尽管听力损失的程度严重甚至极度, 很少有患者接受CI治疗, 这是意想不到的。

Introduction

The impact of hearing loss is wide and can affect health and well-being [Citation1]. Dual sensory loss increases the levels of anxiety and depression and negatively impacts quality-of-life (QoL) [Citation2]. Untreated hearing loss generates huge costs in the health and social sectors [Citation3].

According to the Swedish National Board of Health [Citation4], equal health care and treatment should be delivered irrespective of age, gender and disability. In particular, there is a need to focus on hearing health care rehabilitation, especially regarding gender and age differences.

In Sweden, the estimated prevalence of adult patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss is approximately 20,000, corresponding to 0.2% [Citation5]. In Great Britain, and based on clinical data obtained in 2199 adult patients, the prevalence in this group was estimated to be 0.7% of the general population [Citation6].

Hearing-disabled patients with cochlear implants (CIs) report better QoL, have better results on speech recognition tests [Citation7], get more independent and improve their social life more than was found in patients with no CI [Citation8]. CI implantation, when performed in the elderly, is both safe and useful, and age does not influence CI outcomes. Older CI users show the same speech performance outcomes as younger patients, even after 10 years post implantation [Citation9]. There is no upper limit age for getting a CI; instead, general health should form the basis when selecting patients for an implantation [Citation10]. A recent study by Turunen-Taheri et al. [Citation11] in which 4286 adult patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss were included showed that being fit with a CI was an important factor that benefitted from hearing rehabilitation.

In a study performed in Australia and the United Kingdom regarding those qualifying for CI, the prevalence of adults with severe and greater hearing loss who have a CI was estimated to be less than 10%. The exact rate is, however, unknown, but it is growing because of an ageing population [Citation12].

In the USA, Sorkin [Citation13] estimated that only 5% of all possible CI candidates had CI. This is interpreted as a lack of awareness about CI among patients and audiological professionals and may also be because of economic aspects. In a Belgian study, De Raeve [Citation1] compared the prevalence of severe-to-profound hearing loss in Belgium with the number of implantations and found that approximately 78% of deaf children but only 6.6% of adult CI candidates received CI. Hallam et al. [Citation14], in a study of 122 patients (1% missing answers) with severe-to-profound hearing loss, showed that 39 (32%) had CI, 14 (11.5%) wanted CI but had never been offered, 15 (12.5%) had been told they were not good candidates, 12 (10%) could not make up their minds and 40 (33%) were not interested. These studies [Citation1,Citation13] concluded that it was important to raise general awareness of the benefits of CI based on guidelines and cost-effectiveness data.

Hjaldahl et al. [Citation15] showed that the degree of hearing impairment and age of onset of hearing loss influences the use of CI. Patients between the ages of 51–60 years old were more likely to use CI than were patients with earlier-onset hearing loss. Education levels also influence the use of CI. Patients with at least a college degree were more likely to use CI than were patients with only an elementary school education [Citation15].

In a study performed in patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss, patients with the mildest hearing loss were more likely to use hearing aids (HAs) and more likely to use them bilaterally than were those with profound hearing impairment [Citation15].

Regarding options other than technical rehabilitation with HAs and CI, it is important to offer medical and psychosocial rehabilitation [Citation16,Citation17]. Earlier studies suggested that focusing on anxiety and depression should be a priority early in rehabilitation. Participation in group rehabilitation and treatment by a hearing rehabilitation educator were the factors that patients were most satisfied with [Citation11,Citation17].

In Sweden, a Quality Register of Otorhinolaryngology for patients with severe-to-profound hearing impairment has existed since 2005. A new version including a baseline questionnaire and a follow-up questionnaire began to be used in 2015. These registers define severe-to-profound hearing loss as an air conduction pure tone average (PTA) of ≥70 dB hearing level (HL) for the four frequencies 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz (PTA4) in the better ear [Citation5]. The inclusion criteria were a PTA4 ≥ 70 dB HL in the better ear or/and scoring ≤50% in the better ear on a speech recognition test and being ≥19 years old [Citation5]. The general criteria in Sweden for receiving a CI [Citation18] are similar to those for being included in the quality register.

The overall aim of this study was to investigate, based on data from the Quality Register, how many adult patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss who fulfil the above criteria for receiving CI have been rehabilitated with CI. Furthermore, an additional purpose was to analyse the reason for not having been rehabilitated with CI. Gender, age, and communication methods were among the variables investigated.

Materials and methods

Study population

The study is based on data from 1076 patients collected from the national quality register for severe-to-profound hearing loss in adults [Citation5] who were ≥19 years old, from 24 April 2015 to 24 August 2017. A questionnaire was completed in connection with a visit to a clinic.

The study comprises 55.5% (n = 596) males and 44.5% (n = 480) females. Ages ranged from 20 to 99 years old (mean age, 70.6 years old). In the oldest age group (81–100 years old) more were male than female, at 197 (57.5%) and 145 (42.5%), respectively. The average PTA4 was 90 dB and 89.5 dB HL in the right and left ear, respectively. In males, PTA4 was 88.4/88.3 dB HL, whereas in females, it was PTA4 91.7/91.3 dB HL in the right and left ear, respectively. In patients not CI/CI, PTA4 was 88.3/107.3 dB HL in the right ear and 87.9/108.4 dB HL in the left ear. shows TMV4 dichotomised ≤90/>90 dB HL because this was viewed as a reasonable limit to assume that the benefit of conventional HAs decreases.

Table 1. The proportion of patients in different age groups with an air conduction pure tone average for the four frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz (PTA4) for both right and left ear equal or less (≤) than 90 dB HL and more (>) than 90 dB HL.

The baseline questionnaire

The baseline questionnaire contains data on; age and gender, PTA4, speech recognition, communication method, if the patients use HAs or CI, if they have received extended audiological rehabilitation, and their employment and sick leave. It also contains questions about QoL and how satisfied the patient is with their HAs, CI, and audiological rehabilitation [Citation8].

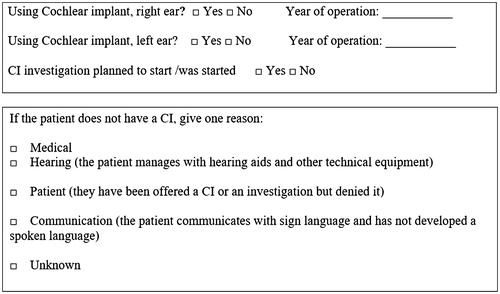

If patients have not been fit with a CI, the patient and a professional determined if they should start a CI investigation or, if not, why they should not wear a CI from among five alternative reasons: medical, hearing, patient, communication or unknown, as shown in .

Extended audiological rehabilitation

Extended audiological rehabilitation is defined as a patient who has received rehabilitation by at least three intervening specialists, e.g. an audiologist, technician, hearing rehabilitation educator, concealer/welfare officer, psychologist and physician, or participated in group rehabilitation.

The ‘estimation scale’ of hearing the impact of impairment on daily life

The quality register contains an ‘estimation scale’ of the impact of hearing impairment on daily life [Citation5]. In this study, we used this ‘estimation scale’ as a measurement for QoL. The ‘estimation scale’ is a self-rating scale that is presented as a visual scale ranging from 0 to 100 [Citation5]. The patient answers the question ‘To what extent does your hearing impairment impact your daily life?’ Zero (0) indicates no impact and 100 indicates maximum impact on daily life. The Swedish quality register defines an ‘estimation scale’ score ≥70 to indicate a strong negative impact on daily life.

Statistical analysis

Statistical calculations were performed with IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 24 (Armonk, NY). The data from the baseline questionnaire and the QoL parameter, ‘estimation scale’, were analysed using unpaired t-tests, and categorical data were analysed using Chi-square tests. The mean and standard deviation were used to summarize continuous data, and percentages are used for categorical data.

In , logistic regression analyses were used to examine the risk of unknown reasons, in the different categories for not having been rehabilitated with CI. Data were coded as ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The relationships among the dependent variable and the independent variables (age, sex, age groups, and type of communications) were studied in each analysis. The first variable in each category of independent variables was the reference variable. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test showed a goodness-of-fit of 0.164. Significance was defined at p < .05.

Table 2. Odds ratios (or) and their 95% confidence intervals for multiple logistic regression analysis (enter) of the unknown reasons for not having been rehabilitated with cochlear implants.

The total number of answers may vary for different questions in the questionnaire.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Stockholm (2014/2101-31). All patients were provided with information before they were included in the quality register.

The patient was able to refrain from entering the registry.

Results

shows the demographic characteristics of the total study population and the differences between patients who were (n = 90, 8.5%) and were not rehabilitated with CI (n = 986, 91.5%). There were significant age differences between the groups: 62.9 years old in the CI group and 71.3 years old in the not CI group. Of the 90 patients with CI, four had bilateral CI (0.5%). Significantly more women (56.5%) than men (43.5%) had been rehabilitated with CI. Most of the patients communicated with speech (97%), but they also used sign language, sign support, and tactile and written language, and they combined two or many languages with each other. HAs were used by 94% of the patients.

Table 3. Demographic characteristics in patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss in Sweden with the proportions of patients with CI and without CI.

shows the proportion of patients in the various age groups with a PTA4 (both ears) greater than 90 dB HL and equal to or less than 90 dB HL. The 61–80 years-old age group had a significantly higher proportion of patients with TMV4 > 90 and ≤90 in the right and left ears, respectively. The table also shows gender differences, with significantly more males (59% and 59.5% in the right and left ear, respectively) than females (41% and 40.5%, respectively) having PTA4 better or equal to 90 dB HL.

shows that 53.5% of the total population had received extended rehabilitation. A significantly higher proportion of CI patients than non-CI patients had received extended rehabilitation (97% and 50%, respectively).

Table 4. The proportion of patients for extended audiological rehabilitation, QoL outcome (estimation scale of hearing impairment impact on daily life) comparing patients with not cochlear implant (not CI) and with CI, crude odds ratios (or) with 95% confidence intervals.

Regarding the QoL estimation scale, there were no differences between the CI and not CI groups.

shows the reasons that patients were not rehabilitated with CI. Furthermore, the table shows whether a CI investigation was started and how the rehabilitation pattern was influenced by age, gender and communication. Hearing reason (33%) was the most common reason for not having been rehabilitated with CI. A total of 244 patients (25%) answered unknown reason.

Table 5. Reasons that 986 patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss not were rehabilitated with cochlear implants.

Patients answering medical reasons (4.5%) had the highest mean age and people with communication reasons (4.5%) had the lowest mean age. The mean age at the start of the CI investigation process was 65.7 years old.

For both males and females, hearing reason was the most common reason, with a slightly higher proportion within the male group, indicating that they managed with HAs and other technical equipment. Unknown reasons were reported by 27% of males and 22% of females. Our results also show that more female patients (20%) than male patients (13%) were in the start-up procedure for a CI investigation.

Comparing different age groups showed that younger patients were more likely to decline CI when offered (patient reason) or because they communicated by sign language (communication reason). Elderly patients were more likely to declare hearing reasons and unknown reasons for not having been rehabilitated with CI. Most CI investigations were started in the age group 61–80 years old.

When we analysed the type of communication, the results showed that among the 94 patients, who used sign support, 29 (34%) declared that they had been offered a CI or an investigation but had denied it (patient reason). In comparison, CI investigations were more frequently started among patients who used written communication.

shows why patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss were not rehabilitated with CI related to extended audiological rehabilitation and QoL measurement. Hearing reason (33.5%) was common within all categories. Twenty-four percent (28%) of the patients who received an extended audiological rehabilitation had started a CI investigation, while only 4% of the patients who had not received extended rehabilitation had done so. Unknown reason was more common among patients who have not received extended audiological rehabilitation (30.5%).

Table 6. Reasons that patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss not were rehabilitated with cochlear implants, comparing with extended audiological rehabilitation and QoL on ‘estimation scale’ of hearing impairment impact on daily life.

Patients with a negative QoL score (estimation scale ≥70) more often started a CI investigation (28%). There were no differences in the proportions of patients with unknown reasons among the QoL categories.

presents a logistic regression analysis that evaluates the risk of not having been rehabilitated with CI for unknown reasons, in the various categories. Significant differences were found between the age groups, with the youngest patients having the lowest risk for unknown reason and the oldest patients (81–100 years old) having the highest risk for unknown reason. Patients using sign support and those who had been rehabilitated with extended rehabilitation had a significantly lower risk for unknown reasons.

Discussion

Despite fulfilling the criteria, only 8.5% of the patients in this study population had been rehabilitated with CI. Two hundred and forty-four patients (25%) answered unknown reason for why it had not been suggested that they undergo rehabilitation with CI. The highest risk for unknown reason was observed in the oldest group of patients (81–100 years old). In contrast, the lowest risk for answering unknown reason was seen among the youngest patients (19–40) and those who had been rehabilitated with extended audiological rehabilitation or used sign support ().

Regarding the other four reasons (medical-, hearing-, patient- and communication), hearing reason was the most common (33%). This should indicate that these patients, despite severe-to-profound hearing loss, were sufficiently rehabilitated by HAs.

Many of the patients may have adapted to life as a hearing impaired individual and learned how to use other strategies, such as sign language and sign support, lip reading and helpful communication manners [Citation17].

The quality register for adult patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss has existed since 2005. Since 2015, the questionnaire has been expanded, and it now contains questions about why patients with such severe and profound hearing loss have not received CI. To date, 1076 patients have been investigated, of whom 90 have CI; the patients came from 17 of 21 county councils. The questions covered whether they had CI and, if they did not, the reason for not having CI. Although the study population has only been collected over a 2.5-year period, it is our conviction that it is representative of how the CI process currently works in Sweden. Generally, the CI patients were more often women, and they were younger and thus comparable to other study populations [Citation11,Citation15].

In this study, patients with CI were significantly more often subjected to extended audiological rehabilitation (). This result was expected because a CI investigation is a comprehensive process during which the patient receives hearing rehabilitation from various occupational categories. This also shows the importance of extended rehabilitation in evaluating and deciding whether CI is an option for the patient. In an earlier study, we showed that group rehabilitation, visits with at least three different professionals, or being rehabilitated with CI, were factors that most positively affected patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss [Citation11].

In this study, there was no difference between patients with CI and the group without CI in terms of estimation QoL (). However, a previous study [Citation11] contained more extensive QoL measurements, and this may explain the lack of difference observed in this study.

Hearing reason (33%) was the most common reason for patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss to not have a CI, with slightly more men than women (). These patients seemed to manage their hearing situation with HAs and other technical equipment. Hearing aid technology has developed tremendously in recent decades and includes wireless systems with blue tooth and FM technology. One explanation for why men use more HAs than CI is that the men in this study had better hearing than was found in the women. Nevertheless, the patient’s ability to use information from speech decreases as hearing loss increases [Citation19]. The degree of hearing loss may explain the use of HAs among patients with severe and profound hearing loss those with the mildest hearing loss are more likely to use HAs [Citation15].

Only 129 (26.5%) patients with hearing reasons have received extended audiological rehabilitation (). One can assume that if they had taken part in more extended audiological rehabilitation and obtained more information about CI, their caregiver might have started a CI investigation.

In the unknown reasons group, there were more men (27%) than women (22%). Among men unknown reason was the second most frequent answer (). The present study cannot explain this gender difference. It is possible that male patients might be more satisfied with the technical aids they are offered or that women have a higher need for communication. In this study, we found that more elderly individuals, ages 81–100 years old (34.5%) responded with unknown reasons. Sorkin [Citation13] discussed that there is a lack of awareness about CI among elderly patients and audiological professionals. This lack may be more pronounced in the rehabilitation process for older patients. Patients who did not receive extended audiological rehabilitation had more unknown reasons (30.5%) (). Our findings also show that patients who are negatively impacted by hearing impairment in their daily life (≥70) more often started a CI investigation (28%) than did patients who were less impacted (<70). This indicates that patients with the greatest need for further rehabilitation are referred to a CI investigation.

Sign support was used by 94 (10%) patients, and 136 (14.5%) used sign language (). Among the community of people who communicate with sign language, individuals are often deaf from childhood and negatively respond to the notion of CI because it influences the deaf culture [Citation20]. There is a significantly lower risk of unknown reasons among patients who use sign support (). The most common reason in these patients was patient reason, which indicated that they had been offered a CI or an investigation but had declined ( and ). If using sign support, they had probably participated in group rehabilitation and were thus aware of CI. We assume that these patients might be satisfied with their communication achieved by using of HAs and sign support and thus were not interested in CI rehabilitation. Other authors have suggested, that communication methods other than speech, such as lip-reading, writing and signing, are also important for communication [Citation14,Citation16]. In the present study, we found that there was no differences in the risk for unknown reasons among those not being rehabilitated with CI except for sign support ().

The literature reports that CI improves QoL, causes better speech recognition [Citation7], and generates more independency and a better social life [Citation8]. In a study by Hjaldahl et al. [Citation15] including data from the quality register [Citation5] of individuals with severe-to-profound hearing loss, 2194 patients were included, of which 10.4% with CI. There seemed to be fewer CIs in the older age groups, but Hjaldahl et al. found no significant difference related to age. In contrast, in the present study, significantly fewer elderly patients (81–100 years old) were rehabilitated with CI (). Some of these differences can be explained by the fact that patients with medical reasons had the highest mean age, 81 years old, in this study (). shows that the highest proportion of patients within the group with a PTA4 higher than 90 dB HL were those in the age group 61–80 years old (42.5%/42.5% in the right/left ear; compare this with the group 81–100 years old, 24.5%/23%). On the one hand, medical reason and hearing reason can explain some of the differences in age among CI patients. However, unknown reason was the most common among the elderly (81–100 years old) (), supporting the authors’ theory that caregivers are not inclined to discuss CI with older patients.

Garcia-Iza et al. [Citation9] found that CI was equally successful from a hearing point of view in the young and elderly (>60 years old). A systematic review by Berrettini et al. [Citation10] also showed that patients with CI improved their speech recognition, and obtained better QoL and that CI was cost-effective even if the patient was implanted after 70 years of age.

It is important to begin a CI investigation early in elderly persons to improve QoL, anxiety and depression and to avoid any possible degeneration of the auditory system [Citation9].

The fact that professionals very often seem to avoid discussing CI with older patients (unknown reason) is one of the most important findings of this study.

Similar to other reports [Citation1,Citation13], the present study indicates that one of the explanations for not having CI is lack of awareness. Hence, it is important to raise general awareness regarding the benefits of CI and to stress the importance of other rehabilitation methods, such as HAs with advanced techniques, taking part in group- and extended rehabilitation and learning sign support, to prevent isolation and a negative impact on QoL among patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss.

The question ‘What is the reason for not having a CI?’ is rather new for both patients and health care providers, and perhaps none of them have previously thought about CI. The most important thing to note is that all hearing professionals are aware of the criteria for CI and can start an investigation if the patient fulfils the criteria and agrees.

Conclusions

The question of why patients with severe-to-profound hearing loss are not rehabilitated with CIs can be answered as follow: medical reason, hearing reason, patient reason, communication reason and unknown reason. In the present study, hearing reason, which indicated that the patient managed with HAs and other technical equipment, was the most common (33%). Unknown reasons was reported by 25% of the patients.

Elderly patients more often responded with unknown reasons (34%) when asked why they have not having been rehabilitated with CI. In contrast, patients who had participated in extended audiological rehabilitation had significantly more CI. Patients using sign support were more likely to have a known reason for why they have not been rehabilitated with CI.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- De Raeve L. Cochlear implants in Belgium: prevalence in paediatric and adult cochlear implantation. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2016;133:S57–S60.

- Turunen-Taheri S, Skagerstrand A, Hellstrom S, et al. Patients with severe-to-profound hearing impairment and simultaneous severe vision impairment: a quality-of-life study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017;137:279–285.

- World Health Organization. Deafness and hearing loss; 2015. World Health Organization (WHO); [cited 2017 Oct 15]. Switzerland (headquarter). Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs300/en/

- Socialstyrelsen. Den jämlika vårdens väntrum-läget nu och vägen framåt. Handbook. The National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen). Stockholm. 2011.

- Swedish quality register of otorhinolaryngology; [cited 2018 May 26]. Available from: www.entqualitysweden.se

- Turton L, Smith P. Prevalence and characteristics of severe and profound hearing loss in adults in a UK National Health Service Clinic. Int J Audiol. 2013;52:92–97.

- Gaylor JM, Raman G, Chung M, et al. Cochlear implantation in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:265–272.

- Maki-Torkko EM, Vestergren S, Harder H, et al. From isolation and dependence to autonomy - expectations before and experiences after cochlear implantation in adult cochlear implant users and their significant others. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:541–547.

- Garcia-Iza L, Martinez Z, Ugarte A, et al. Cochlear implantation in the elderly: outcomes, long-term evolution, and predictive factors. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275: 913–922.

- Berrettini S, Baggiani A, Bruschini L, et al. Systematic review of the literature on the clinical effectiveness of the cochlear implant procedure in adult patients. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31:299–310.

- Turunen-Taheri S, Carlsson P-I, Johnson A-C, et al. Severe-to-profound hearing impairment: demographic data, gender differences and benefits of audiological rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;1–9.

- Rapport F, Bierbaum M. Qualitative, multimethod study of behavioural and attitudinal responses to cochlear implantation from the patient and healthcare professional perspective in Australia and the UK: study protocol. Qual Res. 2018;8:e019623.

- Sorkin DL. Cochlear implantation in the world's largest medical device market: utilization and awareness of cochlear implants in the united states. Cochlear Implants Int. 2013;14:S4–S12.

- Hallam R, Ashton P, Sherbourne K, et al. Acquired profound hearing loss: mental health and other characteristics of a large sample. Int J Audiol. 2006;45:715–723.

- Hjaldahl J, Widen S, Carlsson PI. Severe to profound hearing impairment: factors associated with the use of hearing aids and cochlear implants and participation in extended audiological rehabilitation. Hear Balance Commun. 2017;15:6–15.

- Ringdahl A, Grimby A. Severe-profound hearing impairment and health-related quality of life among post-lingual deafened Swedish adults. Scand Audiol. 2000;29:266–275.

- Carlsson PI, Hjaldahl J, Magnuson A, et al. Severe to profound hearing impairment: quality of life, psychosocial consequences and audiological rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:1849–1856.

- Socialstyrelsen. Indications for unilateral cochlear implant for adult in Sweden; 2011; [cited 2018 Jan 27]. Available from: www.socialstyrelsen.se/SiteCollectionDocuments/nationella-indikationer-unilateralt-kokleaimplantat-vuxna.pdf

- Dillon H. Hearing aids. 2nd ed.; Thieme Medical Publishers Inc. Hong Kong. 2012.

- Baertschi B. Hearing the implant debate: therapy or cultural alienation? J Int Bioethique. 2013;24:71–81, 181–182.