ABSTRACT

Millions of orphans, created by parental deaths due to the HIV/AIDS pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa, live with, and are cared for, by grandparents. Little research has considered how grandparents and, in particular, grandfathers, are caring for orphans. Here, we employ the analytical concept of generative grandfathering to analyse rural grandfathers’ roles in orphan care within communities of Zomba District, Southern Malawi. Using an ethnographic approach to investigate orphan care, we engaged children, young people and adults in multiple qualitative research activities, including interviews, focus group discussions, stakeholder and dissemination meetings. The findings suggest that although grandfathers’ contributions to orphan care are on the periphery of research and policy concerned with grandparenting in Malawi and other regions of sub-Saharan Africa, grandfathers are incontrovertibly at the epicentre of their orphaned grandchildren’s everyday lives. Grandfathers are providers for their orphaned grandchildren, they support their formal education, and are integral to the intergenerational transmission of both knowledge and values. However, despite performing myriad caring roles in plain sight of their communities, grandfathers remain largely invisible due to gendered (mis)conceptions of care. This highlights the dilemma of grandfathers as ageing men who find themselves in roles not traditionally associated with hegemonic notions of masculinity in their communities.

Introduction: Research with and about grandfathers

Many older people in sub-Saharan Africa care for their orphaned grandchildren as a consequence of premature adult deaths due to the HIV/AIDS pandemic and often live in skipped-generation households (Block Citation2014; Schatz, Gilbert & McDonald Citation2013). Yet, research on grandparenting in this region remains limited (Apt Citation2012; Oduaran Citation2014). Notably, despite grandfathers being part of the grandparent dyad, research with and/or about grandfathers in sub-Saharan Africa is particularly limited due to the dominant matrifocal lens through which this dyad is generally understood (Ardington, Case, Lam, Leibbrandt, Menendez & Olgiati Citation2010; Littrell, Murphy, Kumwenda & Macintyre Citation2012), a phenomenon also observed in the Global North (Mann, Tarrant & Leeson Citation2016; Tarrant Citation2013).

The few studies exploring the role of grandfathers’ caregiving in families of sub-Saharan Africa, focus on older people more broadly, rather than specifically on grandfathers as a unit of analysis (for example, De Klerk Citation2011; Kachale Citation2015). This is because, in much of sub-Saharan Africa, caring work is feminised, being associated with feminine roles and responsibilities (for example, fetching water, cooking, bathing children), which are, in many elderly-headed households, undertaken predominantly by grandmothers (Ardington et al. Citation2010; Dolbin-Macnab, Jarrott, Moore, O’Hora, Vrugt & Erasmus Citation2016). AIDS is sometimes referred to as the ‘grandmothers’ disease’ (Shaibu Citation2013) or ‘grandmothers’ burden’ (Cheney Citation2017) because, although it is mainly younger adults who become ill and die of HIV/AIDS, it is widely perceived that it is grandmothers who have the burden of care for their sick and dying adult children and subsequently the responsibility of raising their orphaned grandchildren.

Our research with grandfathers and orphans in rural Malawi challenges these orthodox conceptions of grandparenting, demonstrating that grandfathers are actually at the epicentre of their orphaned grandchildren’s daily lives. We argue, therefore, that hegemonic matrifocal conceptions of grandparenting provide only partial understandings of the realities of grandparenting in sub-Saharan Africa.

Moreover, a small body of grandparenting scholarship from the Global North indicates that grandfathers’ contributions in family care may be underestimated (Mann & Leeson Citation2010; Tarrant Citation2013). Thus, while ‘early scholarship on grandfathers often characterized these men as largely disengaged from research on grandparenting, forgotten in the family system, and concerned primarily with instrumental family matters or play’ (Bates & Goodsell Citation2013, 44), recent scholarship in men’s studies has found grandfathers to be ‘involved in all seven grandfathering work domains: lineage work, mentoring work, spiritual work, recreation work, family identity work, investment work, and character work’ (Mann & Leeson Citation2010, 238). Furthermore, Robin Mann and George Leeson (Citation2010, 238) assert that a ‘new grandfatherhood’ seems to be emerging from investigating grandfathers’ roles and relationships with their grandchildren and there is evidence indicating a departure from more traditional and gendered grandfather roles (described above) to new ones as, for instance, nurturers and mentors (Bates & Goodsell Citation2013; Harper Citation2005).

Our article responds to this identified research need by: 1) investigating the gendered roles of grandfathers and their place as caregivers for orphans in contemporary families in Malawi, thus extending our conceptual understanding of grandparenting of orphans in sub-Saharan Africa beyond a conventional focus on grandmothers; and 2) demonstrating that grandfathers in rural Malawi are engaged in varied generative grandfathering work that shapes their gendered identity and experiences of grandfathering. We use the concept of generative grandfathering as an analytical framework for analysing the role and place of grandfathers in orphan care.

Generative grandfathering

The concept of generative grandfathering derives from European and North American contexts. Generative grandfathering identifies three aspects of grandfathers’ roles and identity, namely biological time (that is, grandfathers are often associated with old age, images of frailty and vulnerability, as well as having grandchildren), historical time or generational cohort (that is, grandfathers are identified and viewed as individuals born in a different generation, hence having different worldviews to that of other generations such as their grandchildren), and genealogical relation of kinship (that is, grandfathers are identified through relatedness within kinship more generally, and their relationship with grandchildren more specifically) (Bates, Taylor & Stanfield Citation2018; Thiele & Whelan Citation2006).

The notion of generative grandfathering is founded on the premise that grandfathers are relational beings and recognise opportunities to teach, care for, and nurture their offspring and other kin (Bates & Goodsell Citation2013; Tarrant Citation2012). Thus, engaged and involved grandfathers actively and willingly expend physical and emotional energy, time, and material resources to care for, serve, and meet the developmental needs and interests of their grandchildren, in addition to building and maintaining amicable intergenerational relationships that are relationally, physically, morally, emotionally, psychologically and intellectually beneficial to both generations and other kin (Thiele & Whelan 2005; Bates Citation2009).

Our study applies the concept of generative grandfathering to the Malawian and sub-Saharan African context more broadly. We argue that the roles and identity of grandfathers who participated in the study reported in this article reflect both the overall notion and the specific aspects of generative grandfathering outlined above.

Context: AIDS and acute poverty

The study was conducted in communities affected by the AIDS pandemic and acute economic deprivation. Malawi is among the ten countries that account for 81 per cent of all people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa (UNAIDS Citation2014). Consequently, Malawi accounts for 4.3 per cent of people living with HIV, 2.8 per cent of people newly infected with HIV, and 6.6 per cent of AIDS-related deaths in sub-Saharan Africa, thus representing 3 per cent, 1.9 per cent, and 4.8 per cent of the global totals, respectively (Government of Malawi, Citation2015; UNAIDS Citation2017). At the time of the study, the country’s HIV prevalence rate of adults 15 to 49 years was 8.8 per cent, but, in southern Malawi where the study was conducted, HIV prevalence at 12.8 per cent was more than double that of the other regions (NSO & ICF International Citation2017).

The many AIDS-related deaths among parents in Malawi, particularly from the early 1990s to 2010, led to increased numbers of orphans in the country (Government of Malawi Citation2014a; NSO & ICF International Citation2017), thus resulting in large numbers of orphans to be cared for. Although the AIDS pandemic has slowed down (UNAIDS Citation2017), the number of orphans due to AIDS remains high in Malawi and other countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Many Malawians, particularly those in rural communities, also face acute economic deprivation, with 51 per cent categorised as poor (that is, living at or below the national poverty line) and 25 per cent being ultra-poor (NSO Citation2014). Zomba District, where the study took place, is the third poorest district in Malawi, with a poverty rate of 70 per cent (NSO Citation2014). The impact of the AIDS pandemic and high levels of poverty present particular challenges for carers, particularly older people such as grandfathers, in providing adequate support for vulnerable children such as orphans.

Methodology

The material presented in this article draws on nine months of ethnographic fieldwork, conducted in Zomba District in rural southern Malawi in 2016. Adoption of an ethnographic approach facilitated detailed exploration of individual and collective knowledges about grandfathers’ caregiving of orphaned grandchildren, capturing localised social and cultural views and experiences.

The study used varied qualitative methods to obtain a range of participants’ views and to triangulate the data, including in-depth, key-informant, photo- and drawing-elicited interviews where the images are used to prompt discussion, focus group discussions (FGDs), stakeholder and dissemination meetings with children, young people, and adults complemented by author fieldnotes.

Sample

Purposive and snowball sampling was used to recruit a total of 142 research participants (80 men; 62 women) from 12 predominantly matrilineal villages within Traditional Authority Kuntumanji in Zomba District. The participants included children and young people (N = 59), grandfathers (N = 15), grandmothers (N = 6), adult community members (N = 43), local leaders (N = 5), and professionals working in the participating communities, including teachers, health surveillance assistants, and NGO staff (N = 14). The sample size and data collection methods are summarised in .Footnote1

Table 1. Sample size and data collection methods

Demographic characteristics of grandfathers

Of the 15 grandfathers in the study, 10 were living in single-headed grandparent households, and most were raising double-orphans (see ), that is, both parents deceased. While many of them had low levels of education and poor economic status, albeit in the broader context of prevalent rural poverty within an agrarian setting dominated by subsistence agriculture, the grandfathers were raising an average of four orphaned grandchildren (with some grandfathers raising up to eight children).

Table 2. Key demographics for grandfathers and their households

Data management and analysis

All audio recordings from the interviews, FGDs, stakeholder and dissemination meetings were transcribed verbatim and imported into NVivo software for thematic analysis (Clarke, Braun & Hayfield Citation2015; Terry, Hayfield, Clarke & Braun Citation2017). This entailed systematically examining the data to identify and code organizing themes (Braun & Clarke Citation2006; Bryman Citation2015) relevant to grandfathering. The data analysis was inductive (data-driven), involving generating codes, themes, associations and explanations after directly examining the data (Creswell Citation2007; Nowell, Norris, White & Moules Citation2017). This entailed reflecting on the research questions and purpose of the study, listening to the audio recordings several times to evoke recollections of encounters with participants, as well as immersion and re-immersion in the data, to inform the analysis (Revsbæk & Tanggaard Citation2015). Analysis involved moving back-and-forth from data (for example, fieldnotes, observations, transcripts) to field experiences (Denzin & Lincoln Citation2018; Peräkylä & Ruusuvuori Citation2018). All three authors were involved in reviewing samples of the transcripts to achieve a robust approach to data analysis. Overall, these systematic steps facilitated rigorous qualitative data analysis.

The epicentredness of grandfathers in orphaned grandchildren’s lives

Discussions with children, young people, and adults who participated in this study yielded several themes indicative of generative grandfathering. Grandfathers in rural southern Malawi emerge among the key network of carers for orphans that also includes surviving parents, grandmothers, uncles, aunts, and elder siblings. Importantly, grandfathers are at the epicentre of their orphaned grandchildren’s everyday lives and are, in some circumstances, the only adult carer. Grandfathers’ roles in orphan care can be captured under three themes, namely: 1) securing livelihoods for their orphaned grandchildren; 2) supporting their orphaned grandchildren’s formal education; and 3) intergenerational transmission of moral, cultural, and religious values including heteronormative sexual education.

Securing basic needs

Material needs

The study revealed grandfathers as central to securing livelihoods for their households. Physically active grandfathers procure essential resources, providing for the daily needs (primarily food, clothing, housing) of their household members, including their orphaned grandchildren living with them:

When I cultivate and harvest crops, I support them [grandchildren]. I sell a bag of rice and buy them clothes, soap (Praise, 74 years, grandfather, in-depth interview).

Health needs

Besides providing essential livelihood resources that are key to their orphaned grandchildren’s health as outlined above, grandfathers also play other roles in addressing their orphaned grandchildren’s everyday hygiene and personal needs, for example, buying them body lotion and soap for bathing, washing clothes, and cleaning utensils. Maintaining good hygiene is crucial for children’s health, especially given the absence of a piped water supply in the research communities. Grandfathers also provide clothes and blankets in the cold season, as well as mosquito nets to prevent malaria during the rainy season, in addition to shoes to protect their grandchildren’s feet from cuts, parasites, and infections. One of the grandfathers describes his role:

I do ganyu, and then when I generate some money, I buy them soap. Sometimes when I generate a little money and see that this child needs clothes, I go and buy them clothes and give them (Nthanda, 86 years, grandfather, in-depth interview).

Socialisation in domestic hygiene practices

In addition to providing resources that promote daily healthy living, grandfathers also encourage their grandchildren to observe and maintain a healthy home to avoid infectious diseases. For example, they encourage their grandchildren to sweep inside the house, the kitchen (usually detached from the main house), and around the compound early in the mornings before leaving for school.

Responding to orphaned grandchildren’s illnesses

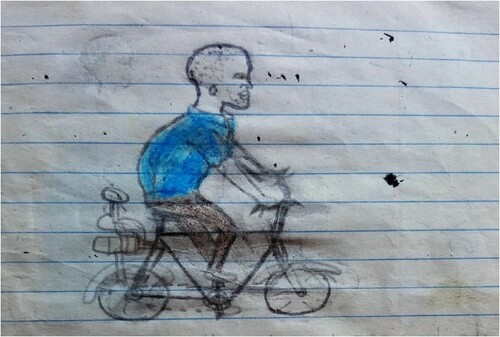

In addition to the roles outlined above, grandfathers take on the responsibility of seeking medical attention for their grandchildren when sick. This is important given the high incidences of malaria, cholera, dysentery and diarrhoea in rural Malawi, particularly during the rainy season.Footnote2 Thus, in the event of serious illness, grandfathers reported taking their grandchildren to a health centre, using their bicycles or kabaza (bicycle taxis), as explained below:

When the children fall ill, I use the money generated from various livelihood activities to take them to a private health facility to access quicker services. I hire a bicycle so that the patient is transported to the health facility as soon as possible (Takondwa, 75 years, grandfather, in-depth interview).

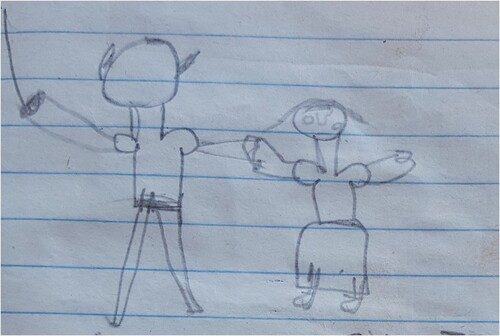

Figure 1. A grandfather taking his granddaughter to a health centre on a bicycle.

Drawing by Orlando, granddaughter, 13 years

Clearly, grandfathers are key to managing the health and wellbeing of their grandchildren. Their role in this context should not be underestimated, especially considering the general socio-economic outlook of Malawi, a resource-limited country with a high disease burden (not only HIV/AIDS) due to lack of capacity to adequately address public health challenges (NSO & ICF International Citation2017) including the recent Covid-19 pandemic. Incidences of illness and poor health are particularly high among the rural population, owing to acute poverty, perennial food insecurity, poor sanitation, and lack of access to improved health services. Rural communities in Malawi consistently register higher rates of malaria, malnutrition, cholera, and other health problems compared to urban areas (NSO & ICF International Citation2017). Ensuring the health needs of children are met is thus an important element of the generative grandfathering work of rural grandfathers, as they strive to keep their orphaned grandchildren healthy.

Healthcare is particularly crucial for orphans in communities affected by HIV/AIDS. Although specific studies addressing this issue are lacking for Malawi, evidence from other regions of sub-Saharan Africa suggests that orphans are likely to have poorer health and developmental outcomes (that is, emotional, psychological, and psychosocial problems) compared to non-orphans (Doku & Minnis Citation2016; Okawa, Yasuoka, Ishikawa, Poudel, Ragi & Jimba Citation2011). This is attributed to the fact that some may have cared for their ill parents, witnessed their AIDS-related death and may experience associated social stigma. They may also lack adequate care and psychosocial support during parental illness and post-parental death (Atwine, Cantor-Graae & Bajunirwe Citation2005), ultimately impacting negatively on aspects of their development such as educational attainment (Bhargava Citation2005).

Supporting grandchildren’s formal education

Most of the grandfathers participating in the study had low levels of formal education. However, many strongly believe in the importance of educating their orphaned grandchildren to create a better future for them. This is exemplified through their commitment to their grandchildren’s education in various ways.

Sending grandchildren to school

Firstly, they send their orphaned grandchildren to school. If/ when the children refuse, are reluctant to go, or wish to skip school, grandfathers use different strategies to persuade them to attend classes such as punishments including withholding food – regarded as a ‘normal way’ of moral socialisation within the local context:

I have to ‘force’ them to attend school. I tell them that, “If you don’t go to school today, you won’t eat nsima “ (Frank, grandfather, 76 years, in-depth interview).

Sometimes it may happen that I don’t want to go to school, so, they force me to go to school […] They tell me that, “If you don’t go to school you won’t have food to eat”. So, because of being wary to miss food, I tell myself that, “should I stay without eating nsima at lunch? It’s better I go to school” (Vitu, 14 years, boy, FGD).

Monitoring grandchildren’s schooling

Secondly, grandfathers who are literate may monitor their grandchildren’s educational progress, for instance, by checking their exercise books. However, only one grandfather in this study, Praise (74 years), a retiree with a secondary school qualification, reported doing this for his two granddaughters. The other grandfathers had little or no formal education; hence they lacked the literacy essential for helping their grandchildren with schoolwork. Chimombo et al. (Citation2000) make similar observations among parents across Malawi, highlighting that high levels of rural illiteracy limits parents’ and guardians’ ability to create conducive home environments that facilitate children’s book-based learning outside the classroom.

However, our study shows that grandfathers who are not highly literate still monitor their grandchildren’s school work by other means. For instance, 75-year old Takondwa, who had himself only attended primary school, explained that he ensures his grandchildren do their homework the same day they are given it after lunch, and before they go out to play, to ensure the children do not rush their homework early in the morning before school.

This suggests that, without grandfathers’ commitment and persistence, some of the children may miss classes, eventually dropping out of school. Notably, grandfathers’ efforts align with various educational initiatives by the Government of Malawi and its development partners in the country (for example, Save the Children, UNICEF, Youth Net and Counselling) that promote children’s school enrolment and attendance as a route to attaining many of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Providing school necessities

Children’s regular school attendance also requires material support. Grandfathers play a vital role in providing their grandchildren with essential items including uniforms, shoes, stationery, pocket money, and mandatory fees. They engage in various livelihood activities to obtain these essential resources for securing their grandchildren’s education. For instance, they farm, do ganyu, and pursue other economic activities such as making mipini (wooden hoe-handles) or weaving madengu (baskets) to sell and use the proceeds to provide their grandchildren’s school requirements:

If there’s 2 tambala [Malawian currency], I say, “Here, use it to buy something to eat”. That school uniform, when that one wears out, they will be sent back from school […] uniform should always be available (David, 80 years, grandfather, in-depth interview).

Grandpa buys us school necessities like exercise books and pens (Orlando, 13 years, girl, photo-elicited interview).

If they don’t have food to eat, they cannot attend school. So, I try my best that I do something to ensure that they have food and are attending school (Praise, 74 years, grandfather, in-depth interview).

A grandfather plays a big part in his grandchildren’s education, particularly, by ensuring that they have food […] because if the child does not receive adequate food, it may affect their health. Consequently, their performance at school declines (Lusungu, 21-year old man, teacher, key informant interview).

Motivating grandchildren

In addition, our research found that grandfathers also play vital roles in motivating their orphaned grandchildren, advising them, and providing other kinds of support, all crucial to their education. They incentivise their grandchildren to work hard at school by rewarding them with praise and gifts. For example, when grandchildren successfully pass examinations, grandfathers may slaughter a chicken as a celebratory treat. They also cite formally educated local role models whom the children encounter (for example, teachers, health workers, members of parliament) to encourage their grandchildren to do well in school. Further, grandfathers warn their grandchildren against poor behavioural choices, which they believe could compromise their education and future such as engaging in premarital sex, smoking chamba (hemp), consuming alcohol, and playing truant:

Grandpa tells us that we should not abscond school. He says that we will regret (Sangalatso, 10 years, boy, FGD).

If the grandfather attended education, he tries that the children should do likewise. If he failed, but has seen others becoming successful because of education, he tries to encourage the children to be like those role models (Lusungu, 21-year old man, teacher, key informant interview).

Escorting grandchildren to school

Some grandfathers in rural Malawi sometimes escort their grandchildren walking to school to ensure their safety and regular attendance. This is particularly important during the rainy season because rivers are often swollen and incidents of children being unable to cross and missing school, or even of being swept away and drowned, are not uncommon. During this period of the year, extensively planted maize also grows tall and thick, while uncultivated open areas and graveyards are densely vegetated, making the paths to and from school extremely risky especially for girls and younger children walking alone, due to possible dangers from hidden assailants (see also Morojele & Muthukrishna Citation2016; Porter, Hampshire, Mashiri, Dube & Maponya Citation2010). Thus, David (80 years) sometimes escorts his two granddaughters (13-year old Orlando and 15-year old Ottilia) to school during the rainy season to ensure their safety.

Overall, given that parent’s/guardian’s poverty and illiteracy are strongly linked to less interest in children’s education (Government of Malawi Citation2004; Maluwa-Banda 2003), it is significant to find that grandfathers in this study all expressed commitments in various ways to educating their orphaned grandchildren despite their own lack of formal education and the many poverty-related challenges they experience in daily life.

Intergenerational transmission of knowledge, culture and values

The transmission of knowledge and values is a core intergenerational task. Grandfathers participating in this study form part of a network of people instrumental in the moral socialisation, intergenerational transmission of culture, religion, livelihood skills, sexual and gender norms to the grandchildren in their care. These are examined in turn below.

‘Moral’ socialisation

There was a common refrain among grandfathers and other adult research participants that ‘children of today’ are more ill-disciplined than previous generations. They suggested that children need to be acculturated into ‘socially acceptable behaviours’, thus assuming a role of dominant moral authority for their orphaned grandchildren:

I strive to stop them from doing bad things […] so that they are on the right path (David, 80 years, grandfather, in-depth interview).

I tell them that, “For you to be a good person, you must respect people, you must respect the elders” (Zolani, 72 years, grandfather, in-depth interview).

Cultural values

The transmission of customs and traditions is a core feature of generational grandparenting. When interviewed, 21-year old Lusungu (male teacher) stated that ‘a grandfather tries his best and that, if he has the culture of a Yao, then his grandchildren should also emulate that culture.’Footnote3 Besides teaching, grandfathers also encourage their orphaned grandchildren to attend cultural events in their communities (for example, traditional dances) to follow cultural/traditional values. Nthano (folktales) are used as a means of conveying key cultural messages especially concerning puberty, initiation, marriage, childbirth, funerals, assets, inheritance, and ancestral roots. Due to the cultural values attached to nthano, grandfathers expect their grandchildren to preserve them by memorising and teaching their friends, as well as future generations:

Grandpa uses nthano to teach us about our culture and about our ethnic group (Sangalatso, 10 years, boy, FGD).

Nthano are intended to teach us about our traditional practices […] So, we listen attentively so that in future, we too, may sit down with our grandchildren and tell them these nthano (Mapula, 20-year old woman, FGD).

Religious values

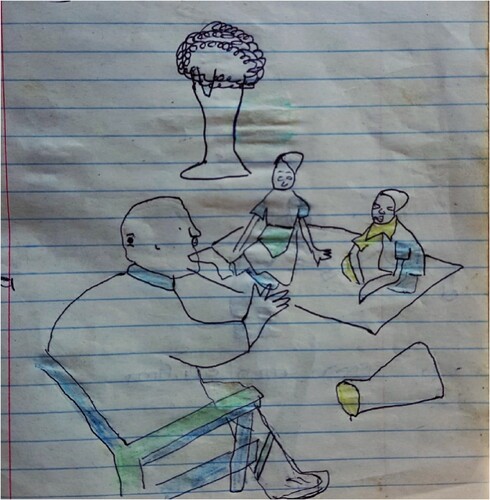

Grandfathers in this study were also instrumental in the intergenerational transmission of spiritual/religious values to their orphaned grandchildren (see also Min, Silverstein & Gruenewald 2017; Patacchini & Zenou Citation2016). Our study shows that grandfathers pray together with their grandchildren at home, take them to places of worship, and encourage various aspects of religious commitment. For instance, Takondwa (75 years) encourages his grandchildren to attend madrasa (Islamic school), takes them to Friday prayers, and teaches them the Koran ().

Heteronormative sexuality

Heteronormative sexuality was regarded as a core cultural value by participants in the research communities (see also McNamara Citation2014) where other sexualities are not acknowledged. Although other researchers report that parents and guardians in Southern African societies rarely discuss sexuality with children (Delius & Glaser Citation2002; Wilbraham Citation2008), socialisation in heteronormative sexuality emerged as key for grandfathers in this study. Grandfathers frequently stated that socialisation in matters of sex and sexuality is particularly crucial in contemporary rural Malawi because of children’s early exposure to pornography and increased sexual experimentation. Grandfathers described enforcing surveillance and monitoring to attempt to prevent their grandchildren from engaging in premarital sexual activities, for instance, restricting their grandchildren’s mobility by imposing curfews requiring them to be home before sunset. However, control differs by gender in that grandfathers are stricter on girls than boys, being wary that granddaughters may become pregnant and drop out of school. Grandfathers also justify stricter surveillance of girls to avoid the potential additional burden of caring for a great-grandchild.

Furthermore, grandfathers teach their grandchildren about bodily and biological changes during puberty, and, from their perspective, the perceived dangers and consequences of premarital sex, as well as the benefits of sexual abstinence, thus warning their grandchildren about the risks of teenage and unwanted pregnancy, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. For instance, 72-year-old Zolani said that he tells his granddaughters to ‘slow down on having sexual relationships with boys’ because ‘these days the world is too dangerous’. Grandfathers expressed similar messages to their grandsons, although, as noted above, they were firmer with their granddaughters.

Gendered livelihood skills

Transmission of livelihood skills and associated gendering emerged as a further strand of generative work for grandfathers in this study. Their contribution in this regard serves two purposes: 1) transmission of livelihood skills/strategies to secure households’ daily needs; and 2) transmission of sociocultural gender values aligning with expectations in their communities.

Like Malawi, much of sub-Saharan Africa remains underdeveloped. Consequently, most daily productive and reproductive work, particularly in rural areas, is undertaken manually, thus being labour intensive and time consuming. Rural households’ survival, therefore, largely depends on the contribution of family members to daily livelihood activities (Abebe & Skovdal Citation2010) such that ‘without the collective action of all family members in labour the multitude of poor families risk destitution’ (Twum-Danso Citation2009, 425). Subsequently, rural children are taught, and are expected, to work alongside other family members to meet daily livelihood needs (Ansell Citation2010; Maconachie & Hilson Citation2016).

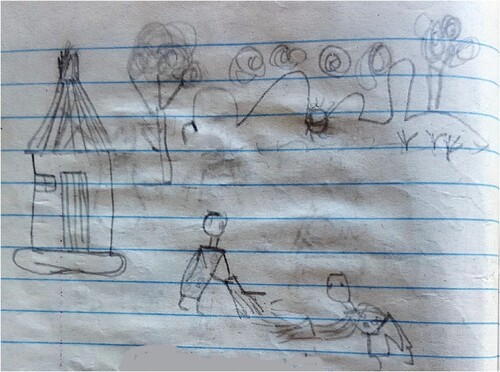

Thus, it was not surprising that inclusion of grandchildren in productive and reproductive work emerged as a key theme of generative work among the grandfathers interviewed in our research. Specifically, grandfathers incorporate their grandchildren into farming and other economic activities (for example, ganyu, small businesses) to augment their efforts to meet everyday household livelihood needs for survival. Children’s socialisation into undertaking household chores begins at a young age (see also Gladstone, Lancaster, Umar, Nyirenda, Kayira, Van Den Broek, & Smyth Citation2010; NSO Malawi & ILO Citation2017) with the volume and difficulty of the tasks evolving as children grow up.

Gender is a key cross-cutting issue for generative grandfathering work and is particularly prominent in relation to livelihood skills. Our study reveals that grandfathers are concerned about ensuring their grandchildren’s future roles as husbands/wives/fathers/mothers, and as men and women in the wider community. The social identities of ‘a real man’ or ‘a real woman’ in the communities in which grandfathers are living are defined by competency in undertaking culturally-defined gender roles for men and women. Echoing what researchers have observed in other rural parts of Malawi (Kambalametore, Hartley & Lansdown Citation2000; Mkandawire Citation2012), a family’s dignity and reputation in these communities could be ‘tainted’ if a child is not socialised ‘properly’ within appropriate gendered social and cultural practices. Thus, as grandfathers socialise their orphaned grandchildren in productive and reproductive work to meet their household’s livelihood survival needs, they align this to expected gender and cultural norms. Yet, grandfathers in our study also ‘un-gendered’ many cultural norms by engaging in myriad feminine roles (for example, caring/nurturing) that women normally undertake. This suggests that the very roles that grandfathers are undertaking simultaneously undermine the reproduction of normative gender roles in their communities. Thus, the findings suggest that generative grandfathering may defy the binary of feminine-masculine roles, where grandfathers are bringing up orphans alone in the absence of grandmothers and other women.

As noted previously in other regions of sub-Saharan Africa (for example, see Edmonds Citation2009; Robson Citation2004), the socialisation of orphaned grandchildren into gender roles in rural Malawi is more apparent in older children (usually aged 8 years and above) than their younger counterparts, in part because younger children may cross gender boundaries more easily than older children who are approaching puberty. Those closer to adulthood are expected to conform more closely to prescriptive social gender norms. Thus, typical gendered productive and reproductive work roles are clear in ways grandfathers socialise their orphaned grandchildren, as reported by participants during interviews (see ).

Table 3. Work for boys and girls

Social norms regarding gendered divisions of labour are transgressed only in exceptional cases. For instance, when a grandfather is raising grandsons or granddaughters only there may be no boy or girl child to undertake a particular gendered task, as well as occasionally when a grandfather does not strictly adhere to hegemonic social norms. Also, as can be noted from , some of the household chores orphaned grandsons and granddaughters are expected to undertake may overlap. For instance, grandfathers teach both their grandsons and granddaughters to sweep around the home compound, sometimes together (), because this chore is not considered exclusively masculine or feminine.

Despite some overlaps, it emerged that, in most cases, the gender divisions of household labour in the bulk of chores are based on gender expectations reflecting wider rural Malawian society. Grandsons are less likely to undertake tasks considered feminine (for example, cooking, cleaning dishes) being wary of ridicule by people in their communities for performing ‘women’s work’. Similarly, girls hardly ever perform chores considered masculine (for example, thatching roofs, herding livestock). These normative gender roles are woven into the fabric of everyday routines of grandfathers and their grandchildren, thus resonating with observations of masculinities and femininities embedded across much of sub-Saharan Africa (Everitt-Penhale & Ratele Citation2015; Morrell, Jewkes & Lindegger Citation2012). Yet, as stated earlier, grandfathers also unsettle these gender norms by undertaking many activities that are otherwise considered feminine in their communities.

It also emerged clearly that traversing gender roles may be considered social transgression, particularly for boys. Although grandchildren living with both a grandmother and a grandfather together generally spend more of their time with their grandmothers than with grandfathers, grandsons in dual-grandparent households are not expected to be involved in undertaking feminine chores (for example, cooking). When they do, they are considered ‘silly’ and ‘a lesser man’ by their relatives and neighbours. Consequently, they are mocked by their peers and the wider community. A research participant summed up prevailing views surrounding gender roles as follows:

Our culture is that a boy shouldn’t be near women and busy spending lots of time with them. The perception is that the women would turn you [the boy] into a sissy. You’ll be a silly person/man if you grow up with a life of a woman. As such, a grandfather is usually busy with a boy, teaching him various masculine tasks that he’d later use when he becomes “a man” (Cristobal, 32 years, man, FGD).

Due to the strict sociocultural expectations of normative gender roles, gender matching may emerge in the socialisation of orphaned grandchildren in dual-grandparent households:

The grandmother is concerned with the girls, and the grandfather is concerned with the boys (Thandi, 57 years, grandmother, in-depth interview).

Grandmothers focus on the girls, like urging them to draw water while the grandfather concentrates on the boys. A grandfather cannot call girls and ask them to cut grass in the bush. I show little attention to the girls, but the most attention is given to the boys (Ishan, 48 years, grandfather, chief, FGD).

The association of women with feminine roles and tasks results in widespread lack of recognition for grandfathers’ roles in orphan care, despite the research reported here very clearly identifying their roles as caring ones. For instance, at the outset of fieldwork during the first contact with 48-year old Ishan (a grandfather and a chief), he asked, ‘Why do you want to talk to grandfathers about care of orphans when care of children is a woman’s responsibility?’ His understanding was, if we wanted to talk about care of orphans, then we should have been talking to women and not men, in this case, to grandmothers and not grandfathers. Having explained that we wanted to understand what role grandfathers play in the lives of their orphaned grandchildren, Ishan curiously agreed to let us engage with research participants in his community. He pondered with scepticism, ‘I want to hear what you find; your work is quite interesting!’ Similar initially sceptical views about grandfathers as carers of children/orphans emerged strongly during (i) a stakeholder meeting at the outset of the fieldwork, (ii) the three meetings with the community advisory group, which Ishan attended, and (iii) during dissemination meetings. The participants stated that this study was unique, and ‘talking to grandfathers as carers of orphaned grandchildren’ was something they had not heard of, or experienced, let alone considered.

This research thus demonstrates that grandfathers play pivotal roles in the lives of their grandchildren. The everyday, mundane, taken for granted, hidden tasks of caring reveal that they are at the epicentre of their grandchildren’s lives and that, far from being on the side-lines, they play critical roles in supporting and nurturing their grandchildren. They are, as we suggest, ‘hidden in plain sight’. Moreover, despite the very strict gendered practices to which they adhere, grandfathers are paradoxically breaching those very norms through the acts of being primary carers for, and raising, children. While acknowledging the limitations of a single-site case study and the socio-cultural specificities of rural Malawi, which is less developed than many parts of the continent, we believe the research findings have relevance for the region and more widely as foregrounded in the following section.

Discussion

The paradox of grandfathers as carers of orphaned grandchildren

Evidence from our study suggests that grandfathers in rural southern Malawi engage in myriad generative grandfathering activities (Bates & Goodsell Citation2013; Tarrant Citation2012) to care for and support their orphaned grandchildren. These generative grandfathering activities revolve around providing for their grandchildren’s material, health, and educational needs, as well as the transmission of knowledge and values vital for their present and future lives. Thus, our study adds to the theoretical and conceptual contributions of the concept of generative grandfathering to Malawi, and the sub-Saharan context more generally. Although generative grandfathering is a concept originating from Eurocentric and North American contexts, its seven work domains emerged clearly among engaged/involved grandfathers who participated in our study. These grandfathers live with, and care for, their orphaned grandchildren. They play a role in lineage work, are viewed by their families and wider society as wardens of culture, fountains of wisdom, and family historians connecting the past and present, hence being key to the intergenerational transmission of knowledge and values. Grandfathers are also custodians of family identity, using nthano to teach their grandchildren about family heritage and what it means to forge lasting and trusting family relationships. They facilitate and participate in leisure activities with their grandchildren (for example, playing bawo (a traditional mancala board game) or going with them to watch traditional dances in their communities). Further, they mentor their grandchildren in practical knowledge and skills preparing them for adulthood. Grandfathers also play a crucial role in spiritual work by providing advice, encouragement, and emotional support during times of need, as well as socialising grandchildren into religious practices. Lastly, grandfathers are stewards of moral character, acting as moral compasses, constructing and shaping their grandchildren’s characters, behaviours, attitudes and beliefs into what is considered socially expected and acceptable, for instance, through discipline.

These roles of grandfathers in rural southern Malawi clearly reflect the seven generative grandfathering work domains identified as typical in European and North American contexts, namely family identity work, lineage work, investment work, spiritual work, character work, and mentoring work (see Bates & Goodsell Citation2013). Thus, generative grandfathering provides an important conceptual lens through which the role and identity of grandfathers in Malawi (as elsewhere) is constructed and can be understood.

As a result of providing generative orphan-care, grandfathers experience heightened self-productivity, which is transformative for them whilst simultaneously unsettling the perspectives of others. It challenges normative gendered expectations of grandfathers – the everyday practices of care/ing grandfathers are not seen, because nobody is expecting them (men) to undertake them. However, the HIV/AIDS pandemic has changed this due to the millions of resultant orphans. Thus, grandfathers must care for their orphaned grandchildren and this has enabled generativity in the sub-Saharan African socioeconomic context that is ordinarily anything but generative.

Our study thus highlights two important paradoxes. The first is the paradox of care. We found that even though what grandfathers do to support and sustain their grandchildren constitutes a fundamental caring role, this work is largely invisible despite taking place in plain sight of their communities. It is neither recognised or identified as such arguably by both community members and the grandfathers themselves. The dominant associations of care with women and feminine roles and tasks, results in grandfathers’ invisibility (see also Cheney Citation2017; Mugisha, Schatz, Seeley & Kowal Citation2015). Grandfathers find themselves in roles not associated with traditional notions of masculinities in their communities and remain unrecognised for their contributions to orphan care. Normative views about gender shape notions of care but, importantly, who gets recognised as a carer of orphans regardless of what contribution each makes in the everyday lives of children. This may explain why research, policies, and programmes on grandparenting and orphan care in Malawi and other countries in sub-Saharan Africa tend to focus on grandmothers, thus overlooking the contribution (including for funding) of grandfathers in orphan care. The findings of our study challenge such gendered conceptions of care and the side-lining of grandfathers in research because hegemonic matrifocal conceptions of grandparenting only provide partial understandings of grandparenting in sub-Saharan Africa.

The second paradox emerging from our study is that grandfathers are challenging and transgressing gender norms despite ironically trying to reinforce them with their grandchildren in everyday life. This is due in part to the absence of women in their households who could share or take responsibility for the care and socialisation of granddaughters, while also wanting to impart and reinforce the gender roles reflected in the wider society in which they live.

Conclusion

This article set out to interrogate hegemonic discourses and narratives of grandparenting and orphan care in Malawi to order to extend and broaden understandings of grandfathers caring for orphans in sub-Saharan Africa. Our study draws from the concept of generative grandfathering to explore and illuminate the specific roles grandfathers play at the epicentre of orphan care in rural Malawian communities affected by HIV/AIDS and poverty. Despite being largely absent in the existing scholarship on grandparenting in sub-Saharan Africa, grandfathers are pivotal in the daily lives and welfare of their orphaned grandchildren and can be located at the epicentre of forms of orphan care. Yet, the evidence from our study suggests that grandfathers remain invisible when issues of orphan care are discussed in public spaces and policy arenas.

We conclude that it is highly problematic to ignore, or overlook, the contribution of grandfathers to orphan care, whilst continuing to recognise that of grandmothers. Thus, there is need to further interrogate hegemonic discourses and narratives of grandparenting and orphan care in Malawi and sub-Saharan Africa to extend and broaden understandings of orphan care generally and in specific country-contexts. Policies and programmes on orphan care in Malawi, and sub-Saharan Africa more widely, need to recognise and respond to the contributions of grandfathers. This would help to align interventions in ways that do not exclude grandfathers based on gender and assumptions that, because they are men, they are not carers of grandchildren.

Disclosure statement

The study was reviewed and given ethical approval by the Geography, Environment and Earth Science (GEES) Research Ethics committee University of Hull, UK at its meeting on 30 October 2015 (no approval number given) and by the National Commission of Science and Technology, National Committee on Research in the Social Sciences and Humanities in Malawi (approval no. P.10/15/62). Permission to recruit participants for the study was obtained from the local authorities in Malawi. Entry into the research site was facilitated by a small international non-governmental organisation through an internship undertaken by the first author. Informed consent was obtained from all adult research participants voluntarily and recorded by written signature. Parents/guardians provided written consent for children under 18 to participate and children’s assent was also obtained in writing. Written consent for publication was given by participants for all drawings included in this article.

This research was funded by a University of Hull PhD Studentship, with additional financial support from the University of Malawi, and the Sir Philip Reckitt Educational Trust.

All authors were involved in the research conception, study design, and analysis of the data. Fieldwork, primary data collection and data coding was conducted by the first author. All authors contributed to drafting and revision of the article, have approved the final version, agree to its submission and publication.

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mayeso Chinseu Lazaro

Dr Mayeso Lazaro is a lecturer in Family Studies in the Human Ecology Department at the University of Malawi. He completed a PhD at the University of Hull, UK, after gaining a Master of Science in Family Ecology and Practice from the University of Alberta, Canada and a Bachelor of Education from the University of Malawi. He has research interests in families, children and young people, the elderly, aspects of rural and community development, as well as ethics and qualitative research methods. He is an experienced consultant who has worked with many international non-governmental organisations including ActionAid, GIZ, Save the Children, UNICEF, and World Vision. Mayeso Lazaro has recently contributed to an edited volume, Rural Gerontology: Towards Critical Perspectives on Rural Ageing (2021).

Liz Walker

Professor Liz Walker is a professor of health and social work research at the University of Hull. Professor Walker has an international research profile within the field of the sociology of health and gender and its applicability to social work. Her expertise in the area of HIV/AIDS in Southern Africa has been influential in the areas of social inequality and stigma. Her recent work focuses on the sociology of with chronic illness, specifically auto-immune conditions. At the University of Hull, Professor Walker is academic lead of the Institute for Clinical and Applied Health Research and lead researcher for the Social and Psychological Aspects of Research into Long-Term Health Conditions Group. She is associate director of the Wolfson Palliative Care Research Centre and chair of the Faculty of Health Sciences Ethics Committee.

Elsbeth Robson

Dr Elsbeth Robson is a reader in human geography at the University of Hull. Dr Robson is a human and development geographer with research and teaching interests in social inequality, ethics and social justice, particularly with respect to women and children/youth. Her research embraces qualitative, participatory and quantitative research methods. Geographically her research concentrates on sub-Saharan Africa. In the UK Dr Robson has been employed by/affiliated with the Universities of Keele, Durham, Liverpool and Brunel and in Africa the University of Malawi and Ahmadu Bello University, Nigeria. She has been a visiting scholar at the University of Zimbabwe, Gothenburg University (Sweden), University of Oulu (Finland) and Leiden University (Netherlands). She was the founding chair of the Save the Children UK Research and Evaluation Ethics Committee, a co-editor for Children’s Geographies journal and recently served on the Council of the African Studies Association UK.

Notes

1 Participants’ names given here are pseudonyms.

2 Malaria is the leading cause of child mortality in Malawi (NSO & ICF International Citation2017) and the leading cause of morbidities in Zomba District, accounting for two-thirds (66.8 per cent) of child and adult mortality (Zomba District Assembly Citation2009).

3 Yao is a major ethnic group in Malawi and predominant in the research locale.

References

- Abebe, Tatek, and Morten Skovdal. 2010. ‘Livelihoods, Care and the Familial Relations of Orphans in Eastern Africa’. AIDS Care 22 (5), 570–576. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120903311474.

- Ansell, Nicola. 2010. ‘The Discursive Construction of Childhood and Youth in AIDS Interventions in Lesotho’s Education Sector: Beyond Global—Local Dichotomies’. Environment & Planning D: Society & Space 28 (5), 791–810. doi: https://doi.org/10.1068/d8709.

- Apt, Nana Araba. 2012. ‘Aging in Africa: Past Experiences and Strategic Directions’. Ageing International 37: 93–103. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-011-9138-8.

- Ardington, Cally, Anne Case, Islam Mahnaz, David Lam, Murray Leibbrandt, Alicia Menendez,and Analia Olgiati. 2010. ‘The Impact of AIDS on Intergenerational Support in South Africa: Evidence from the Cape Area Panel Study’. Research on Aging, 32 (1), 97–121. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027509348143.

- Atwine, Benjamin, Elizabeth Cantor-Graae, and Francis Bajunirwe. 2005. ‘Psychological Distress Among AIDS Orphans in Rural Uganda’. Social Science & Medicine, 61 (3), 555–564. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.018.

- Bates, James S. 2009. ‘Generative Grandfathering: A Conceptual Framework for Nurturing Grandchildren’. Family & Marriage Review, 45 (4), 331–352. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01494920802537548.

- Bates, James S., and Tod L. Goodsell. 2013. ‘Male Kin Relationships: Grandfathers, Grandsons, and Generativity’. Marriage & Family Review, 49 (1), 26–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2012.728555.

- Bates, James S., Alan C. Taylor, and M. Hunter Stanfield. 2018. ‘Variations in Grandfathering: Characteristics of Involved, Passive, and Disengaged Grandfathers’. Contemporary Social Science 13(2): 187–202. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2018.1433868.

- Bhargava, Alok. 2005. ‘AIDS Epidemic and the Psychological Well-Being and School Participation of Ethiopian Orphans’. Psychology, Health & Medicine 10 (3): 263–275. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500412331334181.

- Block, Ellen. 2014. ‘Flexible Kinship: Caring for AIDS Orphans in Rural Lesotho’. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 20 (4): 711–727. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12131.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. ‘Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology’. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2), 77–101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bryman, Alan. 2015. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cheney, Kristen E. 2017. Crying for our Elders: African Orphanhood in the Age of HIV and AIDS. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Chimombo, Joseph, Mike Chibwana, Chris Dzimadzi, Esme Kadzamira, Esther Kunkwenzu, Demis Kunje, and Dorothy Namphota. 2000. Classroom, School and Home Factors that Negatively Affect Girls’ Education in Malawi. Zomba, Malawi: Centre for Educational Research and Training (CERT), Chancellor College, University of Malawi.

- Clarke, Victoria, Virginia Braun, and Nicky Hayfield. 2015. ‘Thematic Analysis’. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, edited by Jonathan A. Smith, 222–248. London: Sage Publishing.

- Creswell, John W. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California, US: Sage Publications.

- De Klerk, Josien. 2011. Being Old in Times of AIDS: Aging, Caring and Relating in Northwest Tanzania. Leiden: African Studies Centre.

- Delius, Peter, and Clive Glaser. 2002. ‘Sex Socialisation in South Africa: A Historical Perspective’. African Studies 61 (1): 27–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00020180220140064.

- Denzin, Norman K., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. 2018. ‘The Art and Practices of Interpretation, Evaluation, and Representation’. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, 757–765. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Dolbin-MacNab, Megan L., Shannon E. Jarrott, Lyn E. Moore, Kendra A. O’Hora, Mariette de Chavonnes Vrugt, and Myrtle Erasmus. 2016. ‘Dumela Mma: An Examination of Resilience Among South African Grandmothers Raising Grandchildren’. Ageing & Society, 36 (10): 2182–2212. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15001014.

- Doku, Paul Narh, and Helen Minnis. 2016. ‘Multi-Informant Perspective on Psychological Distress Among Ghanaian Orphans and Vulnerable Children Within the Context of HIV/AIDS’. Psychological Medicine 46 (11): 2329–2336. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716000829.

- Edmonds, Eric V. 2009. ‘Defining Child Labour: A Review of the Definitions of Child Labour in Policy Research’. IPEC Working Paper.

- Everitt-Penhale, Brittany, and Kopano Ratele. 2015. ‘Rethinking “Traditional Masculinity” as Constructed, Multiple, and ≠ Hegemonic Masculinity’. South African Review of Sociology 46 (2): 4–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21528586.2015.1025826.

- Gladstone, Melissa, Gillian A. Lancaster, Eric Umar, M. Nyirenda, Edith Kayira, Nynke van den Broek, and Rosalind L. Smyth. 2010. ‘Perspectives of Normal Child Development in Rural Malawi: A Qualitative Analysis to Create a More Culturally Appropriate Developmental Assessment Tool’. Child: Care, Health & Development 36 (3): 346–353. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01008.x.

- Government of Malawi. 2004. The Development of Education in Malawi. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Education, Science and Technology.

- Government of Malawi. 2014a. Global AIDS Response Progress Report (GARPR): Malawi Progress Report for 2013. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health & Population.

- Government of Malawi. 2014b. National Girls’ Education Strategy. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Education, Science & Technology.

- Government of Malawi. 2015. Malawi AIDS Response Progress Report. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health and Population.

- Harper, Sarah. 2005. ‘Grandparenthood’. In Cambridge Handbook of Age and Ageing, edited by Malcolm L. Johnson, Vern L. Bengtson, Peter G. Coleman, and Thomas B.L. Kirkwood, 422–428. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kachale, Blessings T. 2015. ‘Elderly Carers: The Experiences of the Elderly Caring for Orphans and Vulnerable Children in the Context of HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Chiradzulu District, Malawi’. PhD diss., Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, Scotland.

- Kambalametore, Sylvia, Sally Hartley, and Richard Lansdown. 2000. ‘An Exploration of the Malawian Perspective on Children’s Everyday Skills: Implications for Assessment’. Disability & Rehabilitation 22 (17): 802–807. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280050200304.

- Lansford, Jennifer E., and Kirby Deater-Deckard. 2012. ‘Childrearing Discipline and Violence in Developing Countries. Child Development 83 (1): 62–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01676.x.

- Littrell, Megan, Laura Murphy, Moses Kumwenda, and Kate Macintyre. 2012. ‘Gogo Care and Protection of Vulnerable Children in Rural Malawi: Changing Responsibilities, Capacity to Provide, and Implications for Well-Being in the Era of HIV and AIDS’. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 27 (4): 335–355. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-012-9174-1.

- McNamara, Thomas. 2014. ‘Not the Malawi of our Parents: Attitudes Toward Homosexuality and Perceived Westernisation in Northern Malawi’. African Studies 73 (1): 84–106. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2014.887747.

- Maconachie, Roy, and Gavin Hilson. 2016. ‘Re-thinking the Child Labor “Problem” in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Sierra Leone’s Half Shovels’. World Development 78: 136–147. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.012.

- Maluwa-Banda, Dixie. 2004. ‘Gender Sensitive Educational Policy and Practice: The Case of Malawi’. Prospects 34 (1): 71–84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PROS.0000026680.92752.3b.

- Mann, Robin, and George W. Leeson. 2010. ‘Grandfathers in Contemporary Families in Britain: Evidence from Qualitative Research’. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 6 (3), 158–172. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2010.498774.

- Mann, Robin, A Tarrant, and George W. Leeson. 2016. ‘Grandfatherhood: Shifting masculinities in later life’. Sociology 50 (3), 594–610.

- Min, Joohong, Merril Silverstein, and Tara L. Gruenewald. 2018. ‘Intergenerational Similarity of Religiosity over the Family Life Course’. Research on Aging 40 (6): 580–596. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027517723076.

- Mkandawire, Elizabeth. 2012. ‘Socialisation of Malawian Women and the Negotiation of Safe Sex’. Master’s diss., University of Pretoria, South Africa.

- Mkandawire, Paul, Issac Luginaah, and Jamie Baxter. 2013. ‘Growing up an Orphan: Vulnerability of Adolescent Girls to HIV in Malawi’. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39 (1): 128–139. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12002.

- Morojele, Pholojo, and Nithi Muthukrishna. 2016. ‘“My Journey to School”: Photovoice Accounts of Rural Children’s Everyday Experiences in Lesotho’. Gender & Behaviour 14 (3): 7938–7961.

- Morrell, Robert, Rachel Jewkes, and Graham Lindegger. 2012. ‘Hegemonic Masculinity/Masculinities in South Africa: Culture, Power, and Gender Politics’. Men & Masculinities, 15 (1): 11–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X1243.

- Mugisha, Joseph O., E. Schatz, J. Seeley, and P. Kowal. 2015. ‘Gender Perspectives in Care Provision and Care Receipt Among Older People Infected and Affected by HIV in Uganda’. African Journal of AIDS Research 14 (2): 159–167. doi: https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2015.1040805.

- Nowell, Lorelli S., Jill M. Norris, Deborah E. White, and Nancy J. Moules. 2017. ‘Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria’. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1): 1–13. doi: http://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847.

- NSO & ICF International. 2017. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015-2016. Zomba, Malawi & Calverton, Maryland, USA: National Statistical Office & ICF Macro.

- NSO Malawi & ILO. 2017. Malawi: 2015 National Child Labour Survey Report. Geneva: ILO.

- NSO. 2014. Integrated Household Panel Survey 2010-2013: Household Socio-Economic Characteristics Report. Zomba, Malawi: National Statistical Office.

- Oduaran, Akpovire. 2014. ‘Needed Research in Intergenerational Pathways for Strengthening Communities in Sub-Saharan Africa’. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 12 (2): 167–183. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2014.907662.

- Okawa, Sumiyo, Junko Yasuoka, Naoko Ishikawa, Krishna C. Poudel, Allan Ragi, and Masamine Jimba. 2011. ‘Perceived Social Support and the Psychological Well-Being of AIDS Orphans in Urban Kenya’. AIDS Care 23 (9): 1177–1185. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2011.554530.

- Patacchini, Eleanore, and Yves Zenou. 2016. ‘Social Networks and Parental Behavior in the Intergenerational Transmission of Religion’. Quantitative Economics 7 (3): 969–995. doi: https://doi.org/10.3982/QE506.

- Peräkylä, Anssi, and J. Ruusuvuori. 2018. ‘Analyzing Talk and Text’. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna Sessions Lincoln, 669–691. Thousand Oaks, California, US: Sage.

- Porter, Gina, Kate Hampshire, Mac Mashiri, Sipho Dube, and Goodhope Maponya. 2010. ‘“Youthscapes” and Escapes in Rural Africa: Education, Mobility and Livelihood Trajectories for Young People in Eastern Cape, South Africa’. Journal of International Development 22 (8): 1090–1101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1748.

- Revsbæk, Line, and Lene Tanggaard. 2015. ‘Analyzing in the Present’. Qualitative Inquiry 21 (4): 376–387. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414562896.

- Robson, Elsbeth. 2004. ‘Children at Work in Rural Northern Nigeria: Patterns of Age, Space and Gender’. Journal of Rural Studies 20 (2): 193–210. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(03)00047-0.

- Schatz, Enid, Leah Gilbert, and Courtney McDonald. 2013. “‘If the Doctors See That They Don’t Know how to Cure the Disease, They say it’s AIDS”: How Older Women in Rural South Africa Make Sense of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic’. African Journal of AIDS Research 12 (2): 95–104. doi: https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2013.851719.

- Shaibu, Sheila R.N. 2013. ‘Experiences of Grandmothers Caring for Orphan Grandchildren in Botswana’. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 45 (4): 363–370. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12041.

- Tarrant, Anna. 2012. ‘Grandfathering: The Construction of New Identities and Masculinities’. In Contemporary Grandparenting: Changing Family Relations in Global Contexts, edited by Sara Arber and Virpi Timonen, 181–202. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Tarrant, Anna. 2013. ‘Grandfathering as Spatio-Temporal Practice: Conceptualizing Performances of Ageing Masculinities in Contemporary Familial Carescapes. Social & Cultural Geography 14 (2): 192–210. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2012.740501.

- Terry, Gareth, Nicky Hayfield, Victoria Clarke, and Virginia Braun. 2017. ‘Thematic Analysis’. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, edited by Carla Willig and Wendy Stainton Rogers, 17–37. Thousand Oaks, California, US: Sage.

- Thiele, Dianne M., and Thomas A. Whelan. 2006. ‘The Nature and Dimensions of the Grandparent Role’. Marriage & Family Review 40 (1): 93–108. doi: https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v40n01_06.

- Twum-Danso, Afua. 2009. ‘Reciprocity, Respect and Responsibility: The 3rs Underlying Parent-Child Relationships in Ghana and the Implications for Children’s Rights’. The International Journal of Children’s Rights 17 (3): 415–432.

- UNAIDS. 2014. The Gap Report. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- UNAIDS. 2017. Fact Sheet: World AIDS Day 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- UNICEF. 2014. Hidden in Plain Sight: A Statistical Analysis of Violence. New York, US: UNICEF.

- UNICEF. 2017. A Familiar Face: Violence in the Lives of Children and Adolescents. New York, USA: UNICEF.

- Wilbraham, Lindy. 2008. ‘Parental Communication with Children About Sex in the South African HIV Epidemic: Raced, Classed and Cultural Appropriations of Lovelines’. African Journal of AIDS Research 7 (1): 95–109. doi: https://doi.org/10.2989/AJAR.2008.7.1.10.438.

- Zomba District Assembly. 2009. Zomba District 2009 Socioeconomic Profile. Zomba, Malawi: Department of Planning and Development, Zomba District Assembly.