Abstract

While recent historical studies have uncovered the intercontinental reputations of New England alchemists, much still remains to be known about actual attitudes concerning alchemy in the early colonies. Focusing on a corpus of roughly a dozen untranslated, and all but entirely unexamined Latin orations (ca. 200 pages) composed by Harvard College’s presidents and students in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, I argue that these new sources reveal the ambivalent, occasionally antagonistic attitude that educated New England men held towards the art of alchemy. Appreciating what they regarded as, in some cases, selfless, Christian efforts to cure diseases, these Harvard elite speakers still worried that alongside pious investigators had cropped up some self-serving charlatans, those who cared not for the communal promises of the art, but only the base financial reward.

In 1773, then sixty-eight-year-old Benjamin Franklin penned a letter to an old friend of his, Samuel Danforth. The two had much in common. They were both men of impressive minds. Both had reputations as renowned scientists. And, both were fathers. “Living-on in one’s Children,” the aging Franklin wrote to Danforth with dry reflection, “is a good thing.” Still, there was something further the pair might aspire to. Franklin fancied “it might be better to continue living ourselves at the same time” – a bold claim for any parent, especially a soon to be septuagenarian. Explaining himself, the founding father continued: “I rejoice therefore in your kind intentions of including me in the Benefits of that inestimable Stone, which curing all Diseases, even old Age itself, will enable us to see the future glorious State of our America.” The future that Franklin imagined was to be a celebratory one. “Over that well-replenish’d Bowl at Cambridge Commencement,” Franklin and Danforth, along with a cadre of “twenty [or] more of our friends” would relish in “jolly conversation.” Franklin bubbled with optimism, signing off as Danforth’s “most obedient humble servant […] for an age to come and forever.”Footnote1

Needless to say, that promise of infinite age fell flat; Danforth laid to rest in 1777, Franklin in 1790. This well-rehearsed anecdote, however, has proved to be an enduring favourite among historians of science.Footnote2 By “benefits of that inestimable stone,” Franklin undoubtedly refers to alchemy’s philosophers’ stone. Upon his death, Danforth enjoyed immediate recognition for his scientific acumen.Footnote3 Scholars have noted in this letter the seeds of alchemical ambition, but have overlooked a means by which further research on the topic might be pursued. At the end of his missive, Franklin refers, albeit cryptically, to “that well-replenish’d Bowl at Cambridge Commencement.” Here, the eighteenth-century polymath discusses the Harvard commencement exercises. Year after year, New England’s educated elite gathered in Cambridge to celebrate the bachelor’s and master’s degree candidates at the early college. The event, to boot, definitely deserved Franklin’s description of a “well-replenish’d Bowl,” as the commencement festivities had a long-standing reputation for rowdiness, for gallons of wine consumed, for punch-drunkenness, so an alumnus jested, that could render one blind.Footnote4 Even amid the revelry, however, there always existed soberer spots of reflection on contemporary events. Might then commencement, the very place that Franklin envisions as fitting for the alchemically inclined to convene, be a similarly apt one to look for source material on the topic?

Admittedly, chasing references to alchemy in commencement proceedings might seem, on first mention, akin to hunting down the very recipe for the philosophers’ stone itself. Many colonial American academic writings no longer exist, either consumed by flames that occasionally ravaged Harvard’s libraries, or lost to that more imprecise force of time.Footnote5 Those materials that do survive have not always attracted the eyes of trained historians – and with good reason. Indeed, the extant manuscripts containing speeches delivered at the Harvard commencement are almost all written in classical Latin, providing an incalculable linguistic hurdle for many, if not most, American historians.Footnote6 Even as one particularly dedicated American classicist edited many of these writings in the 1970s, the orations have still been relegated to the realm of arcana, the overlooked, if not entirely forgotten.

By taking up Franklin on his imagined commencement conversation, and by primarily examining a corpus of roughly a dozen untranslated Latin commencement addresses (ca. 200 pages) composed by Harvard College’s presidents and students in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, it turns out that a more nuanced picture of the attitudes, aims, and apprehensions to New England alchemy emerges. When properly contextualised within existing scholarship, these new references to alchemy in commencement speeches indicate the ambivalent, occasionally antagonistic attitude that educated New England men had towards the art. Appreciating what, in some cases, they regarded as selfless, Christian efforts to cure disease, these Harvard elite speakers still worried that, alongside pious investigators, had cropped up self-serving charlatans, those who cared not for the communal promises of the art, but only base financial reward. Such traffickers in nostrums and panaceas, outsiders of the college, most perturbed the fourth Harvard president Urian Oakes in his 1678 oration: “Such is the character of some men, who gape with their mouths wide open at money to such an extent that they forget humanity.”Footnote7

Alchemy in the classroom: history, historiography, and examples

In his seminal work on the so-called “New England mind,” twentieth-century historian Perry Miller made clear a supposed Puritan disdain for alchemy. According to Miller, New England men and women widely believed that while God might turn water into wine, humans could perform no similar miracles. “For this reason,” the Harvard historian explained, “New England divines never had any tolerance for astrology, the philosopher’s stone, or incantation, for any device by which men sought to escape the rules of nature or to circumvent the settled order of things.” Contemporaries well understood that mines of gold existed in the earth, but “no magic shall ever turn the nature of one metal into another.”Footnote8 This rejection of alchemy evidently held weight, as Samuel Eliot Morison, a contemporary and colleague of Miller’s, expressed a similarly jaundiced view of alchemy in his seminal works on the history of education. Morison, though, noticed something amiss when it came to a certain student by the name of George Starkey. After graduating from the nascent college, the young boy returned to London, where he made a name for himself as a particularly precocious alchemist. Morison admits that Starkey “served the devil more faithfully than he did God. But that was after he had left New England and become a chemist.”Footnote9 As has become evident, the pair of Harvard historians, groundbreaking in their own time on so many subjects, missed the mark on this particular front.

The historiography on the attitudes and practices of alchemy in colonial New England has replaced both Miller and Morison. Among others, William Newman and Lawrence Principe have rekindled the fire of alchemical interest for the better part of two decades. The scholarly fruits emerging from the academic workshop have been nothing short of paradigm shifting. Newman and Principe contend that beginning in the eighteenth century, Enlightenment thinkers increasingly laboured “to legitimize their discipline and enhance their status by divorcing themselves sharply from the foregoing alchemical tradition, which had fallen into disrepute.”Footnote10 Like a tear in the historical fabric left unpatched, this manufactured gap between science and alchemy would grow wider with time. “Nineteenth-century occult writers claimed that the alchemists did not aim primarily at changes of a chemical kind but rather used chemical language and terminology only to couch spiritual, moral, or mystical processes in allegorical guise.”Footnote11 In a rather circular display of logic, obscurity and impracticality became the markers of actual alchemists, thus reinforcing the presumed division between science and alchemy.Footnote12

While many pious writers before, be it Martin Luther in sixteenth-century Germany or Cotton Mather in seventeenth-century New England, respected alchemical imagery as an apt allegory for religious purification, alchemical research still remained synonymous with scientific inquiry for the better part of the early modern period. Indeed, the terms alchemy and chemistry “were not used with any consistent difference of meaning.”Footnote13 Frequently focused on medicine, alchemy embodied a form of knowledge that could be studied like most sciences. Newman, for instance, has shown that young Starkey actually began his research on alchemy while a student at Harvard.Footnote14 Further, it was this New England boy who would publish under an alter-ego (Eirenaeus Philalethes), and quickly rise to the rank of the alchemist in seventeenth-century Europe, a figure who captured the attention of preeminent men like Robert Boyle, Samuel Hartlib, and Isaac Newton. Even as Starkey criticised his early education, it was at the early college that he precisely began his alchemical study.Footnote15 Further, it was the method of disputing, note taking, and logically piecing apart academic readings that formed the backbone of Starkey’s later laboratory notebooks.Footnote16 In certain circumstances then, an early Harvard education provided the right ingredients for alchemical study, and maybe even success.

Beyond Starkey, there are at least two concrete figures who frequently crop up in scholarly literature as would-be harbingers of an alchemical golden age in early New England. While both Leonard Hoar and Charles Morton rightly merit mention in the history of science, neither provides that unimpeachable image of alchemical instruction that recent scholarship now takes for granted. To start with Hoar: the 1672 English immigrant’s scientific ambitions are well known. Deliberately electing this “doctor in phisicke” as the third Harvard president, the governing bodies of the college and the colony initially looked upon the new leader with hope.Footnote17 After all, Hoar was well embedded within a certain elite circle of international scientists. Writing to Robert Boyle in 1672, the newly appointed president boasted of his bold plans for young boys: “A large well-sheltered garden and orchard for students addicted to planting; an ergasterium for mechanic fancies; and a laboratory chemical for those philosophers, that by their senses would culture their understanding, are in our design, for the students to spend their times of recreation.” Hoar noted, “readings or notions only are but husky provender.”Footnote18 In interpreting this plea for Boyle to help fund some of these scientific endeavours, Patricia A. Watson astutely concludes that the missive “implies that there were chemical ‘philosophers’ already under [Hoar's] tutelage.”Footnote19 Still, it is hard to say what chemical pursuits, if any, students actually pursued.

In the case of Hoar’s actual academics, there is very little that can be concluded with certainty. Judging by a programmatic, scolding letter the Englishman penned to his nephew studying at Harvard college in the mid-1660s, Hoar undoubtedly had high standards; he expected reading that would go above and beyond the curriculum, note taking that would encompass “all and singular the most misterious arts and sciences.”Footnote20 But likewise Hoar had his limitations, which rarely garner the slightest mention in scholarship on his supposed impact.Footnote21 In 1675, Hoar was removed from his presidency under mysterious circumstances that would cast a shadow over the institution for years to come.Footnote22 It is hard to imagine much robust instruction, alchemical or otherwise, occurring in an academic institution where students and instructors were fleeing, board members were resigning in mass, and the president was facing a looming dismissal. Hoar’s contact with Boyle offers a tantalising account of educational ambition, but one that likely never came to fruition.

Still, another ambitious Englishman appears frequently in early New England alchemical scholarship, and whose impact can be more properly assessed. In 1685, Charles Morton immigrated to the new world in hopes of revitalising Harvard, a struggling institution at the time. Though he never did receive the presidential post (he believed) he had been promised, Morton remained involved in the college. In time, he earned a sturdy reputation as a proponent of scientific and alchemical education. In order to provide a possible glimpse into the actual reality of any alchemical instruction at early Harvard, previous historians have relied, albeit imperfectly, on the manuscript textbook that Morton composed. With varying degrees of ebullience from scholars, the seventeenth-century instructor has enjoyed almost blush-worthy praise. Employing a touch of presentism, Morison waxed poetically:

Morton […] was the principal agent for spreading in New England the scientific discoveries of the ‘century of genius,’ and preparing people for the ‘century of enlightenment.’ His book was the first to inculcate among Harvard students that observing and curious attitude toward the physical world which, in modern times, marks the educated man.Footnote23

While there can be little doubt that Morton’s compendium occasioned a marked shift in the number of scientific questions – indeed, even the very topics – that students could tackle as part of their degree requirements, it can hardly be asserted with certainty the exact impression, if any, of alchemy that schoolchildren actually received.Footnote27 Newman provides perhaps the most sober suggestion for interpreting the Englishman’s alchemical impact: “Although Morton maintains a calm reserve in the treating of the subjects, he is far from condemning them. Perhaps for that reason, they made excellent topics for academic disputation at Harvard.”Footnote28 Compared to unbridled panegyrics like Morison’s, Newman’s comment itself displays a “calm reserve.” But “far from condemning” hardly appears an indicator of strong support, and hints that Morton’s attitudes might not be summed up with certainty of proponent or opponent.

Without dissecting the entirety of this manuscript physics textbook, it is possible to briefly exhume an overlooked ambivalence to certain alchemical pursuits in New England teaching. Markedly more wide-ranging than other extant tutor-composed compendia, Morton’s work covers diverse topics.Footnote29 Beyond the rudiments of the Aristotelian and new sciences, students would have learned a variety of tales and tidbits: how many hours an average man can mine without exhaustion, the market rate of tin, and the bartering practices of Native Americans and Africans when it came to precious metals. When examining the virtues of gold, Morton includes a much-cited paragraph on alchemy. “The transmutation of all mettals into Gold” by means of purification is “cal’d the finding of the Phylosophers stone.” The seventeenth-century pedagogue indicates historical examples of the “Adepti, Sons of Art, Sons of Hermes,” who are reputed to have actually executed the transformation, and among whom can be counted “Paracelsus, Vanhelmont, and others of whom we shall not farther Insist.”Footnote30 Importantly, Morton peppers his discussion of alchemy with numerous disclaimers (e.g. “as they speak,” “tis said,” “some say”) – qualifiers that, conveniently enough, rarely seem to make it into the spliced quotations of scholarly literature on the topic. Elsewhere in his chapter on metals and minerals, Morton evidently views great medicinal and mechanical benefit to base elements, but provides a far-from exalted image of the alchemist. In the textbook’s section on silver, the Harvard tutor bemoans those “who also pretend to make factitious silver by a lower preparation of their phylosophers stone.” Apparently, these counterfeit measures are “too well known by the knaves [who] Cheat by false Plate, or Mony.”Footnote31

Furthermore, if this instructional work is probed for clues beyond just the individual chapter on metals, the certitude of Morton’s unwavering appreciation for alchemy shrivels. For instance, in the section on syllogisms a student would have learned that the resemblance of one item to another does not signify the two items are the same. By way of example, Morton explains: “no like is the same, for likeness is a relation between divers things: so Alchymy (or fictitious gold) is no gold, bec[ause]: it but Resembles it, and so blanched copper does silver.”Footnote32 This casual, almost offhanded rejection of “Alchymy” (i.e. an imitative alloy of gold) as “real” gold, and the reference again to counterfeit silver hardly inspires universal confidence in the “Adepti.”Footnote33 Likewise, in a chapter on “the species of Animall, Brutes, and Men,” Morton affirms the folly of manufactured (fake) gold. In proving the point that “falsehood in the former begets falsehood in the latter,” the tutor offers another explanation: “[F]or if I apprehend Alchymy to be Gold, I readily (though falsely) affirm (this is Gold).”Footnote34 The point in this particular passage is hard to miss: all that glitters is not gold.

Of course, it must be cautioned that no level of textual analysis could uncover entirely the science instructor’s so-called “real” attitudes; no fancy analytical footwork could bridge that classic gap between facta and verba. Similarly, on the student level, it remains difficult to determine what a young boy would have made of Morton’s compendium, which historically Harvard students took great pains to copy out into their notebooks and minds.Footnote35 At the very least, a more comprehensive perusal through the textbook indicates a much more skeptical attitude towards alchemy built into the Harvard curriculum. In order to isolate and examine this tension further, we must follow the advice of Mr. Franklin, shifting our gaze from the classroom to the outdoor commencement theatre.

Alchemy at commencement: Urian Oakes

At their heart, early modern graduation proceedings were insiders’ events. Commencement was the type of thing that anyone with any connection to the college eagerly attended year after year, wistfully writing down their reflections in their diaries. The proceedings at once reified and reinforced the boundaries between the learned and the lay. As New England historian David Hall comments, “[Harvard commencement] dramatised the privileged situation of the clergy, for only someone trained in oral discourse could follow what was happening. Privilege was a matter of techniques, but also of a special language.”Footnote36 An entirely lacking knowledge of Latin would have precluded an audience member not only from following academic disputations, but also would have further disqualified him from an even more exciting ordeal: the oratio. Speaking to their own class in a language that had required years of dedicated study, Harvard presidents were able to air frustrations in markedly blunt manners; they could take on contemporary critics with unique vigour. Given the penchant for polemic, it should come as no surprise that manuscript editions of the orations were never, strictly speaking, published in their entirety and circulated to a wider public.Footnote37

Admittedly, no commencement oration chiefly concerns itself with alchemy. In the larger framework of a twenty-five-page speech, alchemy does not even stand out as the main topic. Nonetheless, if the historian approaches source material as an investigator might a crime scene, it is the smallest of details, the asides, the subtle and surprising frays in the narrative thread that often reveal the most.Footnote38 In the case of fourth Harvard president Urian Oakes, one need not look any further than his 1677 oration to examine overlooked commentary on alchemy. To be sure, Oakes does not delve into the discussion of the art directly. First, he sums up the “complaint of the times,” that “tasteless minds, good for nothings, mad little men, rabble-rousers from the streets” gain more repute than “men who should be truly revered.”Footnote39 In the eyes of the Harvard president, scattered around Cambridge were men “who with disgust look down upon all academic learning, and do not blush to profess that they can become distinguished orators in three days, and (as if by some leap) theologians exceptionally revered, indeed by their judgement.”Footnote40 The raw frustration on the part of Oakes underscores a clear social divide. Just as with traditional governments, so too with intellectual communities like the learned Res Publica Litterarum, there was always a distinction between the intellectual and the outsider; the former was to receive his proper praise, while the latter was to understand his proper societal position. While the point might easily be dismissed as elitist provocation by today’s standards, it is important nonetheless to follow Oakes as he relates his rhetoric to alchemy.

Rounding out his lament of indigent ministers who suffer (so the Harvard president contends) from meagre pay, Oakes immediately shifts his oratorical eye to the state of doctors in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and iatrochemistry (i.e. medicinal chemistry):

And [this] has not certainly more plainly happened with the learned doctors among us than with [our] ministers; whose most praised occupation in fact not only female quack physicians, but also any whatsoever mechanics and workmen, rush and take hold of; it has come finally to this point, that not only sons of Apollo but also of Vulcan practice that revered art of healing.Footnote41

Left to their own devices, Oakes fears that these apparently unconventional alchemical physicians could erode confidence in doctors more widely. By way of example, Oakes clarifies his worry: “But if some metal-forging workman should know how to be cured most effectively from a four-day fever by his own veterinary medicines, this certainly will have to be feared, not that the fever, so much as that workman should be cited later for insulting doctors.”Footnote42 It is therefore not so much the private practice individuals may resort to for personal healing that rankles the Harvard president. Bluntly put, Oakes seems to accept that the workman – through whatever crude or “veterinary” means – might heal himself. But when that healing becomes public, it might usher in a concommitant spectre of suspicion and cast a shadow of doubt on “real” doctors. Clearly engaging in a delicate dance of social delineation between bad and good, Oakes is careful to qualify himself. In a rare instance of reticence, the president immediately thereafter resolves: “But I should now control myself, so that I do not annoy our alchemists [Spagyrici], who as fireworking ones [Πυροτεχνιται] certainly do not come from the family of Asclepius, but should be considered the offspring of Vulcan.”Footnote43 Considering that Oakes had just railed against alleged quacks, it is rather perplexing that he would then take heed in upsetting alchemists.

The best way to reconcile this apparent discrepancy in the oration might lie in just one word: “our” (nostri). The alchemical doctors that Oakes cares to defend are presumably those educated at the college itself – those invited to commencement, those equipped with the lingusitic skill to follow the Latin speech, and those who might have taken offense at broader generalisations that assailed their art. Indeed, Oakes was far from condemning the pursuit of alchemy as a whole. In 1679, the college president, along with prominent minister Cotton Mather, went out of their way to connect one promising alchemist and physician to Robert Boyle. In their letter of introduction, Oakes and Mather praised William Avery, “who hath Taken great Paines in medicinall studyes especially in Chymicall operations, and made Considerable progresse therein […] when some other physitians have not had the like successe.” For Avery especially, “[G]od hath blessed his endeavours very much for the healing of diseases.”Footnote44 Although the letter fails to detail Avery’s exact achievements, it makes clear nonetheless the existence of pious alchemists close to the academy. In contrast to “other physitians [who] have not had the like successe,” the Harvard educated and Harvard connected could achieve certain results. Throughout his orations, Oakes makes clear in fact the ways in which the early college nurtured doctors. Upon bewailing the outbreak of communicable diseases such as measles, the college leader ornately extolled the instutition in his 1678 speech, likening Harvard to an ancient academy “from which Athenaeum, as if from a Trojan horse, not only innumerable leaders in fact went forth but also distinguished men, who partly as political leaders, partly as ministers, partly as doctors have undertaken excellent work for the Republic and the churches.”Footnote45 In short, if there were men to provide cures to the sick, they would come from the college. And, as it turned out, some did.

Considering that commencement offered an opportunity for the learned community to congregate in one place, it likewise furnished the possibility of remembering those whose death precluded participation. In commemorating distinguished alumni since deceased, Oakes’s eulogies provide a gateway into broader societal values. Though not mentioning alchemy directly, Oakes undoubtedly refers to the art, and stakes out the proper grounds by which Harvard graduates might pursue research into it. The specific individual that enables the college president to advance a larger agenda about alchemical activities was Samuel Brackenbury (1646–1678), “most experienced in the art of medicine, long ago a student of this academy.”Footnote46 In sketching out Brackenbury’s virtues, Oakes is ever mindful to likewise adumbrate the vices of others:

This Brackenbury was no rash fraud [empiricus], who once he has accepted a doctor’s fee claimed by his own authority [the ability] to kill without punishment, but should be numbered among the accomplished doctors, a man of unique zeal, skill, and wisdom for examining forces of nature and causes of diseases, and accurately hunting down their cures, whom as a doctor even that great Aristotle himself would approve.Footnote47

Echoing longstanding historical complaints about alchemy’s secrecy, Oakes expressed appreciation that Brackenbury “would not hold back the reasoning [and …] care for me like some rancher or ditch digger.”Footnote48 The implication, of course, was that the learned doctor treats his patients with a certain respect. Part of that reverence rested in honouring the patient’s desire for rational explanations, for forgoing the obfuscation characteristic of alchemical healing. Similarly, part also came in the ideal healer setting his sights on communal goals. As Oakes exclaimed, “He spared no expense or effort our – alas no longer our – Brackenbury, but in exchange for the small amount of his means, he invested great amounts in exploring the strengths of medicines, so that he would be able to aid humankind as much as he could.”Footnote49 Rather than making money for himself, Brackenbury invested what he could in others. If this almost hagiographic account of the dead doctor seems too one-sided, Oakes makes sure to quickly cast some villains in his tale. True to rhetorical form, after presenting praise, Oakes turns straight to pillory:

Indeed, [Brackenbury] did not carry out and display work for his own benefit, and strive for profit everywhere, allowed or not, just as is the habit of some men, who stand with their mouths wide open at money to such an extent that they forget humanity, but so very much he put his own way of life after the interests of others. That one was not inspired, raised up by his own knowledge or success (just as far too many, who do not boast about and sell [anything] unless their own universal medicines and I do not know what sort of panaceas), but relying on God alone, he dedicated [himself] to the one God, and brought back all things received.Footnote50

Alchemy at commencement: John Leverett

By examining commencement orations decades after Oakes’s death in 1681, it is clear that the perceived problem of greedy alchemists persisted. Furthermore, a close reading of subsequent speeches reveals that future college affiliates, like Oakes, sought to chart the gap between Harvard educated alchemists and allegedly untrained hustlers. Two-faced like Janus, a Harvard president could validate alchemy, only then later to vilify it. Even, or perhaps especially, Harvard students were encouraged to understand what being a pious doctor entailed. In 1697, two decades after Oakes’s last oration, nineteen-year-old valedictorian Elisha Cooke was tasked with delivering the salutary address. Echoing the sentiments of Oakes essentially word for word on Brackenbury, young Cooke professed the cribbed vision of a selfless healer in praising Thomas Graves.Footnote52 It would seem that students were then aware of a certain medicinal mantra, a way of articulating and thereby reinforcing a set of values every time the occasion of a deceased Harvard doctor presented itself. Given the student’s social status, it should be noted that the boy fails to advance any biting critique of alchemists like Oakes did. For more blunt commentary, for the full spectrum of judgements on alchemy, we must turn to more senior college leaders.

In his 1703 commencement address, Harvard senior tutor and fellow John Leverett had a long list of people to praise: the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the lieutenant governor, ministers, high-ranking justices, other Harvard leaders, and Queen Anne (in absentia, to be sure). Such a distinguished audience was in no way remarkable. But Leverett ended his speech in a noticeably new way. Departing from Oakes, who preferred to commemorate dead Harvard alumni earlier in the oration, Leverett concluded with a certain James Oliver (1658–1703): “A most grievous and in no way forgivable omission would it be, if I were to pass over lightly that erudite and gifted philosopher, James Oliver, most experienced in the art of medicine, long ago a student and pride of this academy.”Footnote53 Leverett then proceeds to praise Oliver in precisely the same manner that Oakes – and Cooke – had done for previous doctors, but with a brief addition: “This Oliver was not a rash fraud, but a most wise alchemist.”Footnote54 Not only does Leverett’s comment debunk any clearly defined distinction between the doctor and the alchemist, it goes even further. Leverett’s (uncited) reliance on Oakes’s orations makes more explicit a point that the former Harvard president had only alluded to. So long as one was not “rash” (temerarius), so long as one relied on God and focused on people, not profits, there was no shame in being called an “alchemist” (spagyricus) – and “a most wise” (sagacissimus) one at that. While the Latin, stone engraving on Oliver’s tombstone praised “a man distinguished in the art of medicine,” Leverett, who had studied with and graduated in the same year as Oliver from the college, made it a point to specify that his old friend was an alchemist.Footnote55 But like Oakes, Leverett too had his qualms with alchemy.

Without straying from the corpus of extant commencement orations, it is clear that Leverett went even further, at least privately, than Oakes in critiquing those he viewed as sham alchemists. An important qualification, though, must be made in the case of the 1711 Latin oration. The sole edition of this speech, an autograph manuscript copy, represents something of an outlier because it is not an oration in the singular sense. Rather, Leverett provides what he describes as three draft versions, none of which he actually delivered.Footnote56 While comparing incomplete orations of Leverett’s to presumably final ones of Oakes might seem like likening oratorical apples to oranges, these undelivered speeches merit attention in their own right. When carefully and cautiously engaged, the set of draft compositions takes the researcher inside a speaker’s oratorical workshop and demonstrates how Leverett wavered on what to say about alchemy, how he sharpened critique, only to then cut it out entirely.

In the first draft version, Leverett praises those who graduated from the college that year: “Now among doctors from our own land also are found sons of Asclepius and grandsons of Apollo, who with a modest state of mind love to be called sons of the art of medicine, and are distinguished on the academic catalogue as master’s of the arts [degree holders].”Footnote57 The compliment here seems straightforward enough, and verifiable by contemperary evidence: certain boys born in New England, and educated at the college were making names for themselves as competent healers.Footnote58 In contrast, “other men of the same order and grade go to the markets and walk around and pass their time among the merchants.”Footnote59 The reproach, oblique as it may be, clearly evokes Oakes’s orations that likewise reprimanded alchemical doctors for selling all sorts of nostrums and nonsense. Leverett, though, does not dwell on the point in the first draft. Fiercer criticism is to come in the second version.

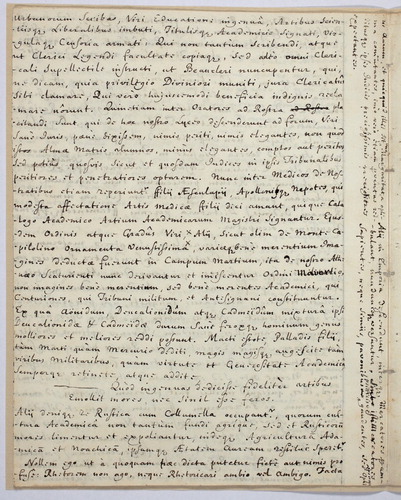

The latter version, on first glance, looks exactly like the former. Again speaking of Harvard graduates, Leverett changes but a single letter, and thereby a single word (quique becomes quoque). The more interesting insertion comes in the margins, written almost after the fact, and without calculating how much space exactly would be needed. To follow the manuscript, one most rotate it 90 degrees and then midway through revert to right-to-left reading. The criss-crossed handling of Leverett’s draft reveals a pointed jab at alchemists ():

Other men of the same order and grade go to the markets, walk among the sellers, and pass their time on the market days. These sellers are wiser than neither monkeys, peacocks, or parrots, rejoicing but selling that golden work and whatever is that one prized pearl for them, and also expecting more generous results and revenues than those most precious Indian [profits].Footnote60

FIGURE 1. John Leverett, Book of Latin Orations, 1711, no. ii, seq. 23. HUD 712.90, Harvard University Archives. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:17454975$23i. Reproduced with permission from the Harvard University Archives. Notice the insertion in the right-hand margin of the manuscript, which includes alchemical discussion.

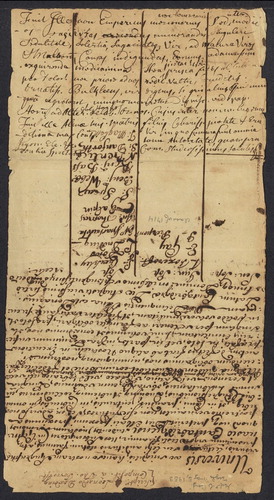

Evidently interested in continuing to both celebrate, but also demarcate the appropriate bounds of alchemy, Leverett returned to the topic years later. In a hitherto unattested oration, the college president praised one of New England’s better known alchemists, Gershom Bulkeley (1636–1713).Footnote61 Preserved like a palimpsest on a piece of recycled, mangled paper, this new source material does not make for easy reading.Footnote62 The Latin content of the scrap plainly reveals that it is part of a commencement oration, but its authorship is not explicitly revealed. Nonetheless, given that the speech commemorates alumni who died in 1713, and given that Leverett was still Harvard president until 1724, it is safe to conclude that this was a speech of his either in 1713 or 1714. In this newly uncovered (fragment of an) oration, Leverett remained interested in perpetuating praise of proper alchemy. Again, reusing the tropes and the very words of orations past, Leverett emphasised that the nearby colony of Conneticut had “sustained an irreversible loss.”Footnote63 According to the Harvard leader, Bulkeley especially desered respect from his community ():

He was not a money driven fraud nor rash, but [someone who] should be numbered among the accomplished doctors, a man of unique zeal, skill, and wisdom for examining forces of nature and causes of diseases, and exactly hunting down their cures. Oh piety, oh old faith [Virgil, Aeneid, 6. 878]! He’s died. He didn’t come back before to visit you. Most wise, most distinguished in appearance. Bulkeley, a man worthy, if there were anyone else, of never getting sick, never dying.Footnote64

FIGURE 2. Thomas Foxcroft et al., Declaration signed by Harvard students to not speak in the vernacular for one year, 1712 August 23, seq. 1. HUD 712.90, Harvard University Archives. Reproduced with permission from the Harvard University Archives. https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.ARCH:16732625. In order to highlight the relevant discussion of Gershom Bulkeley, this image has been reoriented from the manner it appears on the online viewer.

Conclusion

Judging by the ample discussion of alchemy in the orations hitherto discussed, Benjamin Franklin maybe really did mean it when he foresaw graduation festivities in an aestival Cambridge as the perfect time and place for alchemical inquiry. Of course, within wider scholarship on alchemy in early modern Europe, these new commencement sources do not necessarily represent new attitudes. Even revered alchemists like Harvard educated George Starkey could face criticism (arguably, rightfully so) for monetary motives and side hustles that seemed all too often to forget the divinely inspired vision of healing. Early modern dictionaries occasionally featured polemical rejections of alchemy as “an Art without an Art, which begins with Lying, is continued with Toil and Labour, and at last ends in Beggery.”Footnote66 Within this context, Leverett and Oakes are subtle reminders that new world was connected to old, that recent scholarship espousing visions of alchemical Eden in New England has failed to consider fully more enduring critiques from contemporaries. As Harvard leaders sought to keep alchemy under control and connected to proper instruction and proper practice, it might be fruitful to extend our historical gaze to yet more overlooked institutional orations.Footnote67 We might well lend Franklin a hand, and through methodological, patient reading, put twenty or more historical friends in “jolly conversations […] on this Subject.”

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Note on contributor

Theodore (Teddy) R. Delwiche is currently a first-year PhD student in history at Yale University. He completed his research master's degree in early modern history at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands) in 2020, and his bachelor's degree in classics at Harvard College in 2018. His primary research fields are intellectual history, classical reception, and the history of education, with a particular focus on colonial American Latin texts. His work has appeared in The New England Quarterly, History of Universities, Lias: Journal of Early Modern Intellectual Culture and its Sources, and The Classical Outlook. Address: Kalverstraat 12, Utrecht 3512 TR, the Netherlands. Email: [email protected].

Notes

1 Benjamin Franklin to Samuel Danforth, 25 July 1773. The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Packard Humanities Institute, franklinpapers.org (accessed 1 May 2019).

2 Among others, see Ronald Sterne Wilkson, “New England’s Last Alchemists,” Ambix 10 (1962): 128–38.

3 Ezra Stiles, The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles: President of Yale College 14 March 1776–31 December 1781, vol. 2, ed. Franklin Bowditch Dexter (New York: Charles Scribner’s Son, 1901), 2 October 1777, 218.

4 William Brattle, An Ephemeris of Caelestial Motions, Aspects, and Eclipses For the Year of Our Christian Era 1682 (Cambridge: Samuel Green, 1682), 7. See Samuel Eliot Morison, Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century, vol. 2 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936), 465 for a discussion of some efforts to curb commencement enthusiasm. Evidently, such efforts were not successful. The accompanying note for the day after commencement in a 1764 Boston almanac succinctly read: “many crapulae [i.e. hangovers] today.”

5 Considering that year after year, students would deliver declamations, disputations, and other sundry orations, in the best of all possible worlds, there would be hundreds, if not thousands, of such sources. A much more modest number survives. See Leo M. Kaiser, “Contributions to a Census of American Latin Prose, 1634–1800,” Humanistica Lovaniensia: Journal of Neo-Latin studies 31 (1982): 164–89.

6 Meyer Reinhold, Classica Americana: The Greek and Roman Heritage in the United States (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1984), 17: “There were no American intellectual historians with sufficient training in Greek and Roman antiquity, and no classicists with sophisticated knowledge of American history.”

7 Urian Oakes, 1678 Oratio, as transcribed in Leo Kaiser, “The Oratio Quinta of Urian Oakes, Harvard 1678,” Humanisica Lovaniensia 19 (1970): 485–508, on 497–8. ita ut ingenium est nonullorum, qui usque eo pecuniis inhiant ut humanitatis obliviscantur. All translations in this paper are my own. Throughout, I will refer to the available editions of the Latin texts expertly edited by Kaiser but will make occasional reference to the original manuscripts when necessary. Finally, in the interest of readability and accessibility, I will for the most part relegate the Latin speech to the footnotes, notwithstanding particularly pertinent items that require philological and/or textual commentary.

8 Perry Miller, The New England Mind: The Seventeenth Century (Boston: Beacon Press, 1956), 227.

9 Morison, Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century, vol. 1, 41.

10 William R. Newman and Lawrence M. Principe, “Some Problems with the Historiography of Alchemy,” in Secrets of Nature: Astrology and Alchemy in Early Modern Europe, ed. Anthony Grafton and William R. Newman (Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 2006), 385–433, on 386.

11 Newman and Principe, “Some Problems,” 388.

12 Newman and Principe, “Some Problems,” 401–8 for a spirited rejection of the what the authors view as lackluster, yet influential reasoning of Carl Jung on psychology and alchemy.

13 William R. Newman and Lawrence M. Principe, “Alchemy vs. Chemistry: The Etymological Origins of a Historiographic Mistake,” Early Science and Medicine 3 (1998): 32–65, on 33.

14 William R. Newman Gehennical Fire: The Lives of George Starkey, an American Alchemist in the Scientific Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994): 14–54. Interestingly enough, Starkey’s roommate, John Allin (1623–1683), also actively pursued alchemy for the better part of his life. For rich research on Allin, see Donna Bilak, “Alchemy and the End Times: Revelations from the Laboratory and Library of John Allin, Puritan Alchemist (1623–1683),” Ambix 60 (2013): 390–414; and Bilak, “The Chymical Cleric: John Allen, Puritan Alchemist in England and America (1623–1683)” (PhD diss., Bard College, 2013).

15 For an edition (with both the original Latin and an English translation presented) of Starkey’s manuscript, with an autobiographic account of his alchemical progress, see George Starkey, Alchemical Laboratory Notebooks and Correspondence, ed. William R. Newman and Lawrence M. Principe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 331–2.

16 For an examination of how Ramean philosophy taught at early Harvard college heavily influenced Starkey’s practices and procedures of experimentation, see William R. Newman and Lawrence M. Principe, Alchemy Tried in the Fire: Starkey, Boyle, and the Fate of Helmontian Chymistry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 156–207.

17 Records of the Governor and Colony of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in New England 1644–1657 ed. Nathaniel Shurtleff, 5 vols. (Boston: William White,1854), vol. 4, 536.

18 Leonard Hoar to Robert Boyle, 13 December 1672. As printed in in Morison, Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century, vol. 2, 645. There is some evidence that Hoar actually did pursue these goals, albeit in a more modest fashion. In 1672, the Harvard president successfully petitioned the Massachusetts Bay Court for funds to renovate his kitchen and add fencing for orchards. See Records of the Governor and Colony of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, vol. 4, 537.

19 Watson, The Angelic Conjunction, 108.

20 Leonard Hoar to Josiah Flynt, 27 March 1661. As printed in Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century, vol. 2, 641.

21 For instance, otherwise meticulously detailed, Walter W. Woodward’s, Prospero’s America: John Winthrop Jr., Alchemy, and the Creation of New England Culture 1606–1676 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010) mentions Hoar’s ambitions, but overlooks the evident failure.

22 For the most complete overview or Hoar’s presidency, see Morison, Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century, vol. 2, 390–415. For an overview of the limited other scholarly literature on the topic, see also Mark A. Peterson, “Hoar, Leonard (1630?–28 November 1675),” in American National Biography (Oxford University Press, 1999; online ed., 2000), https://doi-org.yale.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0100409\ (accessed 10 May 2019).

23 Morison, Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century, vol. 1, 249.

24 Bernard Cohen, “The Beginning of Chemical Instruction in America: A Brief Account of the Teaching of Chemistry at Harvard Prior to 1800,” Chymia 3 (1950): 17–44, on 21.

25 Watson, The Angelic Conjunction, 109.

26 Woodward, Prospero’s America, 202.

27 See Morison, Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century, vol. 2, 580–639 for an edition of the commencement theses from extant seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century broadsides. The increase in scientific theses, and even ones directly on alchemy, is clearly occasioned by Morton’s arrival.

28 Newman, Gehennical Fire, 36.

29 For comparanda, see Rick Kennedy, Aristotelian and Cartesian Logic at Harvard: Charles Morton’s A Logick System & William Brattle’s Compendium of Logick (Boston: Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1995). Kennedy transcribes other student manuscript compendia and examines schools of philosophical learning at the college during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

30 Charles Morton, Compendium Physicae, ed. Theodore Hornberger and Samuel Eliot Morison [Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Volume XXXIII, Collections] (Boston: The Society, 1940), 121.

31 A nearly identical comment appears in the 1703/04 work of the English Athenian Society, The Athenian Oracle: Being an Entire Collection of All the Valuable Questions and Answers in the Old Athenian Mercuries, 2 vols. (London: Andrew Bell, 1703–1704), vol. 2, 179.

32 Morton, Compendium Physicae, 223.

33 It is important to note that “alchymy,” in early modern English parlance, could refer to a brass like substance, or more figuratively, as trickery or deception. Oxford English Dictionary, online ed., s.v. “alchemy, n. and adj.” (accessed 5 March, 2020).

34 Morton, Compendium Physicae, 201.

35 For a discussion of student practices of copying out compendia such as notebooks, see Thomas Knoles, Student Notebooks at Colonial Harvard: Manuscripts and Educational Practice, 1650–1740 (Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, 2003).

36 David Hall, Worlds of Wonder, Days of Judgment: Popular Religious Belief in Early New England (New York: Knopf, 1989), 65.

37 David Hall, Ways of Writing: The Practice and Politics of Text Making in Seventeenth-century New England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008) argues, for instance, that considering manuscript productions “is the key to understanding how dissent could be expressed in a society that placed a high value on consensus” (2). For more on the culture, context, production, and transmission of commencement orations, see Theodore Delwiche, “Vilescunt in Dies Bonae Literae: Urian Oakes and the Harvard College Crisis of the 1670s,” LIAS: Journal of Early Modern Intellectual Culture and its Sources 46 (2019): 29–58.

38 This likening of the historian to the investigator is not my invention. See Carlo Ginzburg explores the comparison of a historian to a detective in “Clues: Roots of a Scientific Paradigm,” Theory and Society 7 (1979): 273–88.

39 Oakes, 1677 Oratio, 423. Si querelam Temporum contexere liberet, equid potius se nobis offeret Lamentandum quam res eo rediisse, ut Insulsa Capita, Vappae, Cerebrosi Homunciones, Concionales e Triviis homines multo sint apud Vulgum gratiosiores, quam Viri vere Reverendi, singularibus Divini Spiritus donis Cumulatissimi.

40 Oakes, 1677 Oratio. Ita quidem apud nos sunt, qui fastidiose posthabita omni Academica Institutione, Triduo se fieri posse Concionatores Egregios, et (quasi per saltum) Theologiae Doctores, sua quidem opinione, Reverendissimos, profiteri non erubescerint.

41 Oakes, 1677 Oratio, 424. Neque profecto cum Eruditis apud nos Medicis multo praeclarius actum est, quam cum Theologis; quorum quidem Professionem Laudatissimam invadunt, occupantque non Mulierculae solum Medicastrae, sed et Mechanici quivis, et Opifices; eoque tandem est deventum, ut non Apollinis tantum sed Vulcani quoque filii medendi Nobilem Artem profiteantur.

42 Oakes, 1677 Oratio, 424. Quod si Faber aliquis Ferrarius medicamentis suis Veterinariis Quartanae Febri mederi sciat efficacissime profecto verendum erit, ne non tam Febris illa,quam Faber ille Medicorum opprobrium in posterum esse Dicatur.

43 Oakes, 1677 Oratio, 424. At reprimam jam me, ne Spagyricis nostris aegre faciam; qui quidem Πυροτεχνιται non e familia prodierunt, Aesculapidum, sed Vulcania proles sunt habendi. Mitto Medicos, qui suis ipsorum Aegritudinibus ac Incommodis mederi norunt.

44 Urian Oakes and Increase Mather to Robert Boyle, 10 October 1679, in The Correspondence of Robert Boyle, ed. Michael Hunter et. al., 6 vols. (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2001), vol. 5, 163. Thank you to William Newman for personally making me aware of this reference. For more on William Avery, see William Newman, “Spirits in the Laboratory: Some Helmontian Collaborators of Robert Boyle,” in For the Sake of Learning: Essays in Honor of Anthony Grafton, ed. Ann Blair and Anja-Silvia Goeing (Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2016), 621–41, on 636–9.

45 Oakes, 1678 Oratio, 490. Ex quo Athenaeo, tanquam ex Equo Trojano, innumeri non principes quidem sed tamen eximii viri exiere, qui Reipublicae et ecclesiis qua magistratus, qua theologi, qua medici egregiam navaverunt operam. It must be noted that Oakes’s comparison of Harvard college to the Trojan horse must refer to sheer numbers of men. The Trojan horse, of course, was the instrument of trickery that led to the destruction of Troy. The lugubrious overtones in referring to the wooden creature should not be taken literally.

46 Oakes, 1678 Oratio, 497. Tandem aliquando ad eruditum et insignem virum Samuelem Brackenburium, medicinae consultissimum, huius olim alumnum Academiae, nostra delabatur oratio. For brief biographical details on Brackenbury, including some accounts of his prescriptions for sick colonists, see John Langdon Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University, 18 vols. (Cambridge: Charles William Sever, 1881), vol. 2, 154–5. The only known publication of Brackenbury’s is an almanac – not surprising since students took great pride and pleasure in printing New England almanacs on the college press. See Samuel Brackenbury, An Almanack for the Year of Our Lord 1667 (Cambridge: Samuel Green, 1667). Watson, The Angelical Conjunction, discusses Brackenbury’s collection of anatomical works, as well as his dissecting practices, 134 and 141.

47 Oakes, 1678 Oratio, 497–8. Fuit hic Brackenburius non empiricus temerarius, qui [ … ] sit humano et accepto sostro impune occidere suo iure sibi vindicarit, sed inter medicos χαριεντας numerandus, singulari sedulitate, solertia, sagacitateque vir ad naturae vires et morborum causas investigandas eorumque accuratius exquirenda remedia. The manuscript features a clear erasure, and I agree with Kaiser’s suggestion that sit humano is extraneous and should have been deleted as well, for it makes little grammatical or contextual sense as is. I also want to thank William Newman for aid in translating empiricus, which is likely a Latinized version of the English “empiric,” a term attested for in the OED to describe untrained, quack practitioners.

48 Oakes, 1678 Oratio, 498. qui, cum ei graviter affecto medicus quidam praescriberet cum authoritate nec ulllam afferet rationem, ne me, inquit, perinde curaris ut bubulam aut fossorem, sed prius doce me causam cur ista praescribas, et habebis me obsequentem.

49 Oakes, 1678 Oratio, 498. Nullo quidem sumptui aut labori pepercit noster – heu, iam non noster – Brackenburius, sed pro modulo facultatum impensas fecit in indagandis et exquirendis medicamentorum viribus quo posset humano generi prodesse quam plurimum.

50 Oakes, 1678 Oratio, 498. Non enim omnem ille operam ad suum quaestum retulit ac traxit, lucrumque undique per fas nefasque captavit, ita ut ingenium est nonullorum, qui usque eo pecuniis inhiant ut humanitatis obliviscantur; sed aliorum commodis suam rem nimium quantum postponit. Non ille vel scientia sua vel successu inflatus erat et elatus (ut nimium multi, qui non nisi panchresta sua crepant et nescio quas panaceas venditant); sed Deo solo fretus Deo uni adscripsit et accepta retulit omnia.

51 Oakes, 1678 Oratio, 498. Quare magnus licet apud nos sit medicorum proventus, magnum tamen sui desiderium apud omnes ordines reliquit eruditus, pius, suavissimus, ac peringeniosus Brackenburius.

52 Elisha Cooke, 1697 Oratio Salutatoria, as edited in Leo Kaiser, “Feriis Festisque Diebus: The Salutatory Oration of Elisha Cooke, Jr., 7 July 1697,” Harvard Library Bulletin 28 (1980): 380–90, on 385–6. For biographical information on Graves, see Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Harvard Graduates, vol. 1, 480–4.

53 John Leverett, 1703 Oratio, 169. Ploranda sane et minime ignoscenda esset omissio,si eruditum illum et insignem philosophum Iacobum Oliverum,medicinae consultissimum, huius olim Academiae alumnum et ornamentum, tacito et sicco pede pertransirem.

54 John Leverett, 1703 Oratio, 169–70. Fuit hic Oliverus non empericus temerarius, sed spagyricus sagacissimus [ … ].

55 See John Langdon Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University, vol. 3, 198–9 for biographical details of Oliver and a transcription of the tombstone. See also Nathaniel Williams and Thomas Prince, The Method of Practice in the Small-Pox (Boston: S. Kneeland, 1752) for praise of Oliver. Extracts of Oliver’s alchemical activities are actually preserved in notebooks of Gershom Bulkeley. See Harold S. Jantz, “Christian Lodowick of Newport and Leipzig,” Rhode Island History 4 (1945): 13–26, on 14–5.

56 John Leverett, 1711 Oratio Draft 3, 400. Caetera desiderantur: intercepta subitanea aegritudine, inque orationis loco substituta fuit oratiuncula intervallo meridiano excogitata. For the oration that Leverett did actually deliver, see Leo M. Kaiser, “John Leverett and the Quebec Expedition of 1711: An Unpublished Oration,” Harvard Library Bulletin 22 (1974): 309–16.

57 Leverett, 1711 Oratio Draft 1, 391. Nunc inter medicos de nostratibus etiam reperiuntur filii Aesculapii Apollinisque nepotes, qui modesta affectione artis medicae filii dici amant, quique catalogo academico artium academicarum magistri signantur.

58 In 1711, for instance, Thomas Robie earned his master’s degree and subsequently gained quite a following as an expert physician. See Frederick G. Kilgour, “Thomas Robie (1689–1729), Colonial Scientist and Physician,” Isis 30 (1939): 473–90.

59 Leverett, 1711 Oratio Draft 1, 391. eiusdem ordinis atque gradus viri alii in emporia descendunt interque mercatores perambulant et versantur.

60 Leverett, 1711 Oratio Draft 2, 396. Eiusdem ordinis atque gradus viri alii in emporia descendunt interque mercatores perambulant nundinisque versantur. Sunt isti mercatores sapientes, neque simiis, pavonibusve, psittacisve, gaudentes sed quoque opus ipsum aurum et quidquid illis sit una margaritata optima commutantes, imo vero etiam proventus redditusque ipsis Indicis preciosissimis preciosiores expectantes. Here, my reading differs slightly with Kaiser’s, which read quoque for ipsum after opus. In regards to Indian profits, Leverett is possibly referring to the East Indian pearl trade.

61 For more on Bulkeley, including several examples of praise upon his death for medicinal and alchemical wisdom, see Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Harvard Graduates, vol. 1, 389–402; and Thomas Jodziewicz, “The 1699 Diary of Gershom Bulkeley of Wethersfield, Connecticut,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 131 (1987): 425–41.

62 Thomas Foxcroft et.al., Declaration signed by Harvard students to not speak in the vernacular for one year, 1712 August 23. HUD 712.90, Harvard University Archives, https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.ARCH:16732625. The first use of the paper is dated to 1712 and represents a pact by students to only converse with one another in Latin, Greek, or Hebrew for a certain fixed period of time. For a transcription and translation of the student text, see Theodore Delwiche, “The Schoolboy’s Quill: Joseph Belcher and Latin Learning at Harvard College ca. 1700,” History of Universities 33 (2020): 69–104, on 76. The relevant portion of the commencement speech runs in backward fashion from sequence two to sequence one. In the interest of emphasizing the dual content of the manuscript, I will hereby refer to it as Leverett’s “1713/14 Oration.” Thanks are due to Christian Flow, for examining a draft transcription of the fragment, and suggesting some possible readings of particularly difficult textual spots.

63 [Leverett], “1713/14 Oration,” seq. 2. Ne ingratus simul ac invenustus essem, silentio, pedeq[ue] (ut aiunt) sicco praeterire non possum, q[uo]d vicina colon<ia > damnum irreperabile sustinuit [ … ].

64 [Leverett], “1713/14 Oration,” seq. 1. Fuit ille non empiricus mercenarius non temerarius sed inter medicos χαριεντας numerandus singulari sedulitate, solertia, sagacitateq[ue] vir, ad naturae vires et morborum causas indigandas, eorumque adamussim exquirenda medicamina. Heu pietas heu prisca fides obiit pro dolor! nec priore ad vos redit. vultu, eruditis[simus] ornatis[simus]. Bulkleeus, vir dignus, si quis alius, qui numqua[m] aegrotaret, numqua[m] moriretur.

65 Oakes, 1678 Oratio, 493. To trace the chain of transmission yet further, Oakes evidently derived his comment on Shephard from a common Latin school text of the time, namely Erasmus’s colloquia. See Desiderius Erasmus, Opera Omnia [ordinis primi, tomus tertius], ed. L. Halkin, F. Bierlaire, and R. Hoven (Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing Company, 1972) (Colloquia: Apotheosis Capnionis de Incomparabili Heroe Ioanne Reuchlino in Divorum Numerum Relato), 276.

66 John Harris, Lexicon Technicum or, An Universal English Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (London: Printed for Dan. Brown et.al., 1704), as quoted in Newman and Principe, “Alchemy vs. Chemistry,” 62.

67 For apt places to start, perhaps the later eighteenth-century commencement speeches of Yale President Ezra Stiles would suffice. For bibliographic information, see Stuart McManus, “Classica Americana: An Addendum to the Censuses of Pre-1800 Latin Texts from British North America,” Humanistica Lovaniensia 67 (2018): 427–67.