Abstract

The Swiss physician and philosopher Theophrastus von Hohenheim, called Paracelsus (1493-1541) is known for his strong advocacy of medical alchemy. That his natural philosophy was tied to medical alchemy is perhaps uncontroversial, but just how it was so is less straightforward. This article provides an insight into the connection between the two by means of Paracelsus’s concept of active agents, with an emphasis on fire, its master Vulcanus, and the associated term Archeus. I will show how these evolved in the thought of Paracelsus by taking an evolutionary view of his works. The complexity of his views comes to light as a result of employing the method of hybrid reading, which integrates the traditional close reading technique with the much more novel one of distant reading. The latter is part of the emerging field of digital and computational humanities, and involves the analysis of corpora by means of digital tools, including computer programming (Python). In the article, I will attempt to combine distant and close reading and showcase how such hybrid reading approaches may provide new insights into historical corpora.

In his late treatise Labyrinthus medicorum errantium of 1538, the Swiss physician Theophrastus Bombast von Hohenheim called Paracelsus (1493–1541) expressed the view that “whatever the fire does is alchemy, likewise in the kitchen as in the oven.”Footnote1 This proposition emphasises the active agency of fire, and sets it in close relationship with alchemy. Furthermore, Paracelsus defines alchemy in the following manner:

[Alchemy] is an art that is necessary and must be. Because in it lies the art of the Vulcanus, it is important to know what the Vulcanus can do. Alchimia is an art, Vulcanus is its artisan.Footnote2

In the present article, I analyse Paracelsus’s related concepts of fire, Vulcanus, Archeus, and alchemy with a threefold aim. First, I aim to provide a bridge between Paracelsus’s matter theory and cosmology on one hand, and his medical alchemy, on the other. Second, I try to map out the evolution of his thought on active agents, focusing on fire, its “master” Vulcanus, and the associated term Archeus. Third, I aim to showcase a hybrid methodology, combining a traditional, “close” reading of Paracelsus’s writings with a “distant” reading based on digital and computational humanities, and especially on tools available in the Python computer programming language.Footnote4 The distant reading approach draws on the Huser Paracelsus corpus, newly transcribed under the supervision of Didier Kahn and Urs Leo Gantenbein.Footnote5 In the following, I will try to demonstrate that hybrid (close-distant) readings open up new insights on Paracelsus’s writings, including on the development of his key concepts over time.

The Paracelsus corpus

Much of Paracelsus’s life was spent in the chaos of the early Reformation, which Paracelsus experienced firsthand and was actively involved in.Footnote6 Yet where Martin Luther (1483–1546) was focused on reforming the Christian religion, Paracelsus aimed even further, at a comprehensive reformation of all knowledge ranging from theology to natural philosophy, medicine, alchemy, and magic.Footnote7 His revolutionary zeal led to an eventful stint as city physician and university lecturer in Basel (1527–1528), where he tried to teach a new approach to medicine. Banned from Basel by end of 1528, Paracelsus led an itinerant life, before settling in Salzburg. Here he died in unclear circumstances at the age of 48.

Paracelsus published little during his lifetime; the main volume was Die Grosse Wundarztney (The Great Surgery, 1536); he also printed prognostications as well as small treatises on syphilis and bathing.Footnote8 The bulk of his work remained in manuscript and were held onto by disciples. Publication began with a trickle in 1552 and 1553, before turning into a flood in the 1560s and 1570s; a high point was 1567, when ten books were published as authored by Paracelsus.

As Paracelsus’s name began selling books, editors and publishers issued works that were of dubious authenticity, if not outright forgeries. Perhaps the most important forgery was Philosophia ad Athenienses (Philosophy to the Athenians), first published in 1564;Footnote9 this work stood at the basis of the influential condemnation of Paracelsus by the theologian Thomas Erastus (1524–1583) in 1571.Footnote10 Separating the authentic Paracelsus from the pseudo-Paracelsian phenomenon began in earnest in the 1580s, when physician Johannes Huser (c. 1545–1600/1601) started editing and printing the collected works of Paracelsus in Basel. His approach was to collect autographs or manuscripts originating from persons deemed trustworthy, such as Paracelsus’s amanuensis Johannes Oporinus (1507–1568) or a foremost contemporary disciple, Johannes Montanus (1531–1604). Huser expressed doubts on certain treatises, but he printed them anyway. His publication effort eventually included ten volumes (published 1589–1591), with a mega-volume of surgical works issued posthumously in 1605 in Strasbourg. Huser’s edition remains foundational for Paracelsus’s studies. Between 1922 and 1933, a new edition of Paracelsus’s works was published by German scholar Karl Sudhoff (1853–1938). The Sudhoff edition controversially modernised the original spelling and introduced a new order of publication based on his views of Paracelsus’s chronology.Footnote11

Both the Huser and the Sudhoff edition of Paracelsus comprise only the medical and natural philosophical works of the Swiss physician. Yet Paracelsus wrote a great deal concerning theology; these treatises remained mostly unpublished until the twentieth century. Starting in 1955, Kurt Goldammer (1916–1997) began the project of publishing the theological works, but only half of Paracelsus’s writings were printed. Since 2009, under the aegis of the Zurich Paracelsus Project (ZPP), Urs Leo Gantenbein began the remarkable task of publishing a New Paracelsus Edition, re-editing eight volumes of Paracelsus’s theology (one of which has already appeared in print).

The ZPP also undertook the pioneering effort of transcribing the Huser and Sudhoff editions, and of making them available through an open database called THEO, which allows in-depth browsing and search functions (). This is a joint project carried out by Gantenbein and Kahn. The Sudhoff edition was mostly transcribed by a special OCR (THEO) designed by Gantenbein, while the Huser edition was done manually by a specialised company.Footnote12

For the purpose of this article, I have chosen to focus on the standard Huser edition of Paracelsus. The limitations of this approach are straightforward: the Huser Paracelsus corpus contains both genuine and inauthentic treatises;Footnote13 it is limited to non-theological works, and it is not chronological. To mitigate these problems, in the following sections, I discuss only those treatises that scholarly consensus considers to be genuine Paracelsus, and I attempted to follow accepted chronology in my analysis.

A hybrid (close-distant) methodology

“Distant reading” is a phrase coined by literary critic Franco Moretti in 2000 in opposition to the prevailing “close reading” paradigm in literary studies.Footnote14 Where close reading emphasised the careful, engaged, and qualitative reading of one text – usually a canonical one – Moretti’s distant reading argued for replacing this with the quantitative analysis of thousands of non-canonical texts. The reason was Moretti’s attempt to map out world literature and account for “the great unread,” a term introduced by Margaret Cohen.Footnote15 Although the term “distant reading” caught on, its meaning evolved. It became associated with computer analyses of large collections of text, not necessarily pertaining to the realm of literature.Footnote16 At the same time, distant reading’s position in relationship with close reading, as well as to quantitative approaches originating from the social sciences became less clear. I argue that there is a hard and a soft view of distant reading; according to the hard view, distant reading is defined by a rejection of reading and of text; its proponents follow the methods of social science.Footnote17 The soft view is less well articulated, but can be characterised as adopting both quantitative and qualitative approaches. It also does not reject the relevancy of close reading.Footnote18

In this article, I adopt the soft perspective of distant reading, which I specifically define as a method of looking at a large corpus of texts that offers a bird’s eye view of it.Footnote19 It is achieved by means of computer-based tools and has both quantitative and qualitative components.Footnote20 My approach further draws on Andrew Piper’s notion of computational hermeneutics. In Piper’s view, close and distant reading intertwine in a circular fashion to create new knowledge.Footnote21 In the conclusions of the article, I will offer my own reflections on the experience of following a hybrid reading methodology, employing close and distant readings to grasp multiple layers of meaning.

My approach to the distant reading component is also to regard it as part of a tradition of textual mining that scholars performed long before the advent of computers. Literary studies have naturally focused on literary texts, particularly fiction. Yet there are models of reading outside this realm that furnish a different insight into the distant reading-close reading models. Texts related to knowledge and learning were not necessarily seen as requiring sequential reading (i.e. a narrative) and often included aids to study such as table of contents, marginalia, concordances, extracts, and indices, as adapted to the codex (book-style) format. Using such aids could allow a preliminary distant reading approach followed by a close reading of only the chapters or passages that the reader of the manuscript or book deemed important. Such practices were developed in the Middle Ages and continued throughout the early modern and modern periods.Footnote22 From this point of view, distant and close reading are not novel hermeneutical approaches, and forms of what we now call distant reading date further back than the late nineteenth century.Footnote23 Today, the prevailing medium of the paper-based book is being challenged by the computer. However, computer-based finding aids remain inferior to paper books as long as the text itself is not machine readable.Footnote24 Contrary to common views, machine-readable text is not readily available in scholarly fields such as history of science, medicine, or knowledge in general (though this is now changing).Footnote25 Machine readability, in turn, offers the possibility of direct searching without the need of editorial intervention. However, as I will further show, the strength of the search and the suitability of the results ultimately depend on both the formulation of the search criteria and the algorithm that provides the answers.

Fire in Paracelsus’s matter theory

My research began with a close reading of Labyrinthus medicorum errantium and its closely-linked terms of fire, Vulcanus, and alchemy. I then focused my analysis on the notion of fire, building on recent research on Paracelsus’s matter theory.

Paracelsus’s view of matter and cosmos was built in dialogue with the prevailing system of thought of his day, which can be described as medieval Aristotelian. This cosmology and matter theory taught during the Middle Ages is fairly familiar to us today. The world below the Moon was made up of four elements: fire, air, water, and earth. The elements were not fundamental; instead, the qualities of hot, cold, dry and wet were their building blocks and came into combination to produce them. In this scheme, fire was the element produced by the qualities hot and dry. The worldview was also hierarchical, with earth being the lowest element and fire being the highest; the elements were, at least theoretically, disposed vertically up to the sphere of the Moon. Above fire lay the sphere of the Moon, which separated the lower world from the higher one; everything above it was made up of an incomprehensible and unattainable fifth essence (quinta essentia) which made up the Sun, the planets and the stars, as well as the invisible realms in between.

This cosmology survived through the Middle Ages, although in the late medieval period it came under question in certain alchemical circles that followed the ideas of the Franciscan dissenter Johannes de Rupescissa (c. 1310–1366/1370) and the writings attributed to Ramon Llull (1232–1316, now accepted to be pseudonymous). Following Rupescissa, it seemed possible that something like the quinta essentia could exist on the earth.

Scholars have established three stages of development of Paracelsus’s theory of the elements.Footnote26 The first stage is associated with Paracelsus’s early work Archidoxis (c. 1525). According to Reijer Hooykaas in 1935, Paracelsus accepted the Aristotelian doctrine of the four elements in his early work Archidoxis (c. 1525, pre-Basel).Footnote27 However, in 2006, Dane Daniel drew attention to the Rupescissan bent of Paracelsus’s views in this treatise.Footnote28 In Archidoxis, Paracelsus conceived of a quinta essentia that can combine with the elements and impart its medical qualities to them.

The second stage is associated with Philosophia de generationibus et fructibus quatuor elementorum (hereafter Philosophia de generationibus). This has been dated by Didier Kahn c. 1527–1530, (i.e. during or post-Basel).Footnote29 The matter theory in this treatise has been described by Daniel and Kahn.

By the time he wrote Philosophia de generationibus, Paracelsus had rejected Rupescissan theory and denied the existence of a quinta essentia either in the heavens or on earth. The elements are now seen differently than according to the traditional worldview. They are described as wombs, matrices, or mothers.Footnote30 They are corporeal and give birth to all things.Footnote31 Here, Paracelsus clearly perceives the topic of generation in sexualised terms.Footnote32

Paracelsus preserves the hierarchical Aristotelian worldview, except the elements are disposed differently.Footnote33 He defines an upper sphere or Globul containing the elements air and fire, and a lower Globul containing the elements of water and earth.Footnote34

In regard to the element of fire, Paracelsus states that it is the same as the luminous stuff that makes up the stars. The fire element is thereby associated with light; Paracelsus calls it, in line with the Latin Vulgate Bible, Firmamentum. Like all other elements, the element of fire can produce both the quality of cold and hot: the sun, for instance, is made up of a white, hot kind of fire (Weisser Candor), while the moon is composed of a red, cold fire (Rott Candor or Diaphanitet).Footnote35 The element of fire is also the originator of both dry and wet phenomena: according to Paracelsus, it generates both day and night, summer and winter, and various meteorological phenomena such as snow, rain, wind and hail.Footnote36

The element of fire is not the same as the fire found on earth. This is material fire (Materialische Fewr); Paracelsus also names it Tristo. There is no explanation as to the choice of this name for material fire, and it never occurs again in the corpus of Paracelsus’s works. However, I suggest that a reason for it may be uncovered in De meteoris.

The element of fire and material fire are connected by means of the Sun, though in an unclear way. To explain the relationship, Paracelsus resorts to a metaphor: there is a “burning mirror” (Fewrspiegel) in the Sun.Footnote37 If this mirror acts in a customary way when kindling wood, it also has some occult influence: Paracelsus maintains that the fire that lies in stones and metals also comes from the Sun.Footnote38 In any case, material fire can be found just as much in water as in stones and is described as a kind of nourishment for the elements.

The third stage of Paracelsus’s matter theory is outlined in De meteoris (not before 1532, according to Kahn).Footnote39 In De meteoris, Paracelsus removes fire as being one of the elements, replacing it with Heaven, Himmel.Footnote40 Himmel is now described as the first element, with the other three elements originating from it.Footnote41 Kahn has pointed out that De meteoris has a much more Biblical and Trinitarian bent than Philosophia de generationibus and that its speculation on Himmel can be related to Paracelsus’s reading of the account of Genesis.Footnote42

Being an element, Heaven is described as a body (corpus); it is also a mother, and its role is to bring forth specific fruit, which are the stars.Footnote43 In turn, fire becomes exclusively confined to the lower material fire described in Philosophia de generationibus. The nature of fire is now compared with death: “fire and death are alike: the fire consumes all and takes them away, just as death does.”Footnote44 Paracelsus also describes fire as a matter (Materia) that transforms primary matter into its ultimate one (Ultima Materia).Footnote45 The notion of primary matter and ultimate matter suggests an Aristotelian teleological background.Footnote46 Fire is also described as a visible death (sichtlicher Todt), while death in itself is unseen (unsichtbar).Footnote47

Although material fire is no longer called Tristo, the word seems apt to describe it, as it resembles the Latin adjective tristis, trista, tristum, sad, or gloomy. Paracelsus had already used the noun tristitia (sadness) in 1525s Archidoxis in association with melancholia;Footnote48 he apparently also employed in his lectures in Basel, as one surviving lecture note mentioned the word tristitia and described it as a form of despair.Footnote49

Paracelsus further clarifies that fire cannot be an element since it produces nothing and has no fellowship with human beings.Footnote50 On the contrary, like death, it separates body from soul. In comparison to Himmel, which is close to human beings and bestows a number of gifts upon them, humans can live without fire. This seems a strange statement given the importance of fire in human existence, but Paracelsus suggests that fire is not an essential prerequisite for human existence, while Heaven is.Footnote51 Thus the production of the seasons and of day and night are now attributed to Himmel, rather than the element of fire, by a process of substitution Paracelsus himself confirms; Heaven “is the element of fire and a mother out of which fire grows and springs from.”Footnote52

The fact that fire does not generate justifies Paracelsus’s move of denying its elementary status. Fire is now seen as a destroyer. Yet, as Paracelsus shows in the further chapters of De meteoris, the function of fire as destructive does not need to be understood in a purely negative fashion. This is because fire is understood as the main instrument in the hands of an entity that Paracelsus calls Vulcanus. With the concept of Vulcanus, Paracelsus introduces notions of alchemy into natural philosophy, effectively denying a boundary between the two.

Vulcanus by distant reading

The Paracelsus corpus is written mainly in early modern High German, although there are treatises wholly in Latin.Footnote53 Yet even where German predominates, Latin words are present and stand out, often denoting specific terms or terminology. Vulcanus is such a Latin term. What is remarkable is that Paracelsus does not just use the Latin nominative forms of a word, but other declensions as well, as will be further shown.

To understand the term Vulcanus and its genealogy, I began by performing a simple search in the THEO database, under the “Search & Browse” tab. Entering the search term as “vulcanus” yields ninety occurrences, which include mentions in the Huser and the Sudhoff corpus. To be more comprehensive, I investigated the stem of the word “vulcanus.” At this point it was not clear whether this is “vulcan” or “vulc.” The result of searching “vulc” in THEO yields 280 results, but upon closer analysis some irrelevant terms were included (e.g. fulciat, fültz). Searching for “vulcan” eliminated the irrelevant findings, yielding 272 results, so I concluded that “vulcan” is the correct stem. THEO proved capable of capturing variants of this stem, yielding such words as “vulcanus,” “vulcanum,” and “vulcanische.” However, since the results include Huser and Sudhoff, their number is overstated. To be as accurate as possible, I opted for a customised search in Python using Regular Expressions (RegEx).Footnote54 This yielded 220 mentions of the stem “vulcan” in the Huser corpus only.Footnote55

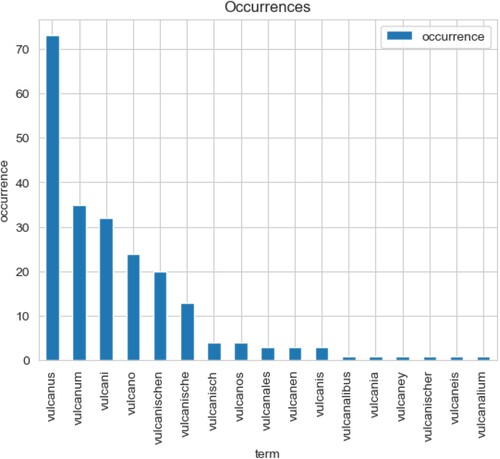

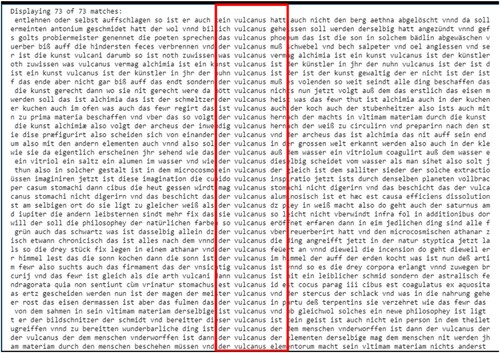

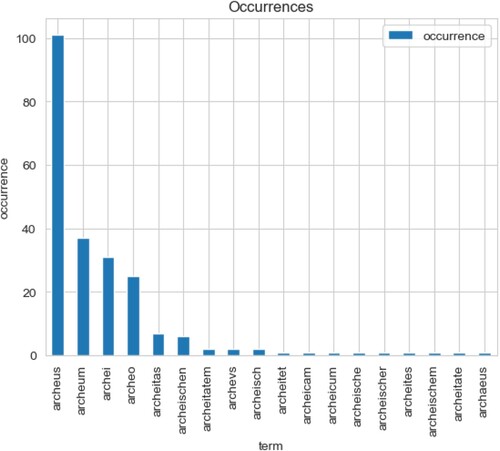

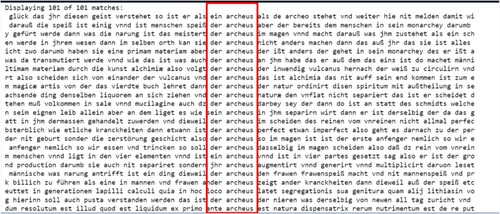

These mentions were then processed through Python’s Pandas data analysis package to count their frequencies; the result is visualised in . The majority of mentions, as expected, are of the Latin nominative vulcanus, which appears 73 times; together with the plural vulcani, the accusative vulcanum and dative/ablative vulcano, they make up 74.5% of the usage of the stem “vulcan.” There are, however, outliers, which include the Germanised adjectives vulcanisch, vulcanische, and vulcanischen, as well as rare occurrences of vulcanales, vulcanalia, vulcanalibus and vulcanalium. The latter seemed different than the normal vulcanus references, so next I employed Python’s NLTK natural language processing package to analyse them by concordance. The concordance function identifies passages where these terms occur, but without further adjustment it cannot point to the treatise titles where they appear. THEO, however, can. Looking at the context, I concluded that these words refer to spiritual entities (Geist / Geiste) associated with fire. The connection between natural philosophical spirits and Geist entities is intriguing; although I will touch upon the subject in the rest of the article, a proper analysis of the subject should be carried out.Footnote56

NLTK provides further useful tools of text analysis that I employed in my study. The concordance revealed that Paracelsus employed the German masculine declension “der” for the term “vulcanus” (see ).Footnote57 This may very well be in line with the view of Vulcanus / Hephaistos as a male god in Greek and Roman mythology, but could also be linked to the traditional perspective of active agency as being male. This gendered view seemed to fit the view of elements as being, metaphorically, female, and suggests the importance of the reproductive metaphor in Paracelsus’s thought.

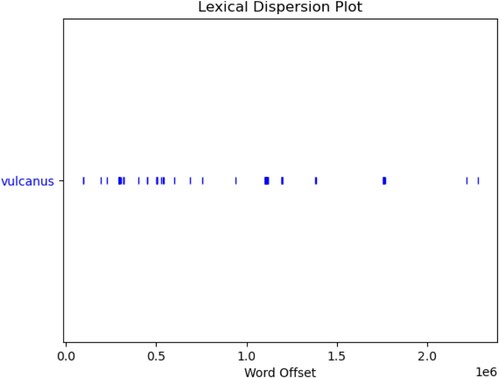

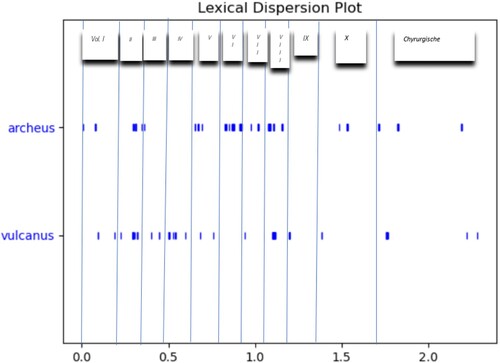

Another useful facility that Python’s NLTK provides is to visualise the distribution of the term “vulcanus” across the Paracelsus corpus via a Lexical Dispersion Plot ().Footnote58 The word distribution shows that Vulcanus appears predominantly at the beginning of the corpus, particularly in volume 2 (15 occurrences), which comprises Paracelsus’s late writings. Other remarkable occurrences are in volume 8 (natural philosophy and meteorology, 22 occurrences) and the surgical writings (18 mentions). This insight has been pursued by close reading further on.

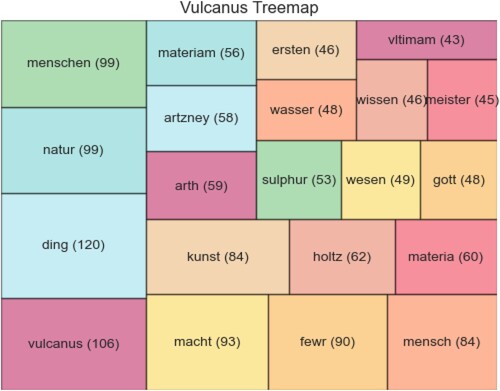

Finally, I used Python’s Counter dictionary to get an insight into the usage of “vulcanus” and its variants by examining words that occur in proximity to it.Footnote59 According to it, Vulcanus associates chiefly with the imprecise word “thing” (ding),Footnote60 but also with the words “humans” (menschen) and, to a lesser degree, “human” (mensch).Footnote61 There are strong co-occurrences of Vulcanus with terms associated with nature, power and activity: natur (99 times), macht (93 times), kunst (84 times). By nature (Natur), Paracelsus seems to refer to common views of it as an active internal agent (physis or Natura), though a separate study might be desirable on this topic.Footnote62 Vulcanus is also, unsurprisingly, well connected with the term “fire”, fewr (90 times). Interestingly, when fire is excluded, the element Vulcanus most closely relates to is water (wasser, 48 times). Materia, materiam is also strongly represented (60, respectively 56 occurrences, for a significative total of 116). A visual representation (treemap) of the associations of Vulcanus is rendered in .Footnote63

Vulcanus by close reading: prior to and in De meteoris

The term Vulcanus may have first appeared in the Elf Traktat and its associated Priores Quinque Tractatus, short treatises that presumably originate from the period before Basel.Footnote64 The treatises deal with various diseases, amongst which Paracelsus places the Farbsuchten, or “diseases of skin coloration”.Footnote65 There are two treatises on the Farbsuchten, and both mention the Vulcanus without much explanation. However, a revealing analogy is made between heaven (Himmel) and the metalworking Artist in the second version of the treatise (Priores Quinque Tractatus: Von Farbsuchten). Just as the Artist lets the Vulcanus cook the minerals or metals, heaven (Himmel) also lets the Sun, the Vulcanus of heaven, cook the earth.Footnote66 The Artist can be seen as either a smith or an alchemist; Paracelsus does not make a clear distinction between the two. The Vulcanus, it seems, is an instrument that the Artist uses; it is connected with the Element of fire (Fewrig Element) and may be identical to it.Footnote67 Here the element of fire does not have the same meaning as in Philosophia de generationibus, as it refers to something that can be found on earth. This confirms the hypothesis that this treatise, at least, was written around the same time as Archidoxis, when fire was still deemed to be a traditional element.

In Liber paragraphorum, which has been dated to Paracelsus’s Basel period, Vulcanus appears again and in much clearer fashion. Here it is referred to as an “Astral master of fire” (Astralisch Fewrmeister), not a “corporeal smith.”Footnote68 The reference to the Roman god of fire and of the foundry is straightforward here, and seems to be an attempt at capitalising on the humanist trend of his age. Astral here does not mean Vulcanus appears only in the stars; it denotes something invisible and incorporeal that can also be found on earth.Footnote69 Vulcanus is described as being found in the human stomach and responsible for digesting food.Footnote70

In comparison to such earlier treatises, in De meteoris, Vulcanus becomes a prominent philosophical concept. Vulcanus is described as a craftsman and a worker (der Fabricator und Werckmann aller dingen) that makes things evolve from their seeds to their ultimate matter.Footnote71 There is a Vulcanus in each element, and it is the driver of the change in created things. In line with the meteorological emphasis of the work, Paracelsus focuses on the Vulcanus of heaven, which “composes, dispenses and orders” the heavenly operations, which include rains, snows or hail.Footnote72 Its presence is warranted by Paracelsus’s definition of the elements as “mothers” and “wombs,” which are described as unmoving. In turn, he postulates the existence of active agents that would prepare the fruit of the elements, again suggesting a reproductive analogy. In this case, the main agent is Vulcanus; as we will shortly see, it is not the only one, but is the most important. Paracelsus insists that Vulcanus should not be understood either as “a spirit or as a person” (kein Geist auch nicht ein Person).Footnote73 In this sense, it should be seen as distinct from Geiste like the Pennates Superi, who are living, rational beings producing phenomena like rainbows.Footnote74

Paracelsus goes further not only to associate the Vulcanus with fire, but actually maintain that fire and “Vulcanus of the humans” (der Vulcanus der dem Menschen) are one and the same thing:

[He, the craftworker] is just as much a workman as the fire, which also works each thing that is placed in it: It melts the metals, consumes the wood into glass; it also prepares many things, and is no spirit, no soul, no person, and yet has in itself such a power to grasp, to take hold, and to prepare wondrous things: [this] is the Vulcanus that is subject to man.Footnote75

It is now clear that fire, now called Vulcanus Ignis or Igneus, is the model for the Vulcanus that exists in each element. The approach is analogical: here, fire is the microcosm, while the elemental Vulcani are the macrocosmic counterparts. The process whereby all things are produced, including snow or flowers, are henceforth seen in a similar manner as an art produced by separation and extraction.Footnote76

At this point, Paracelsus complicates the account by adding two other active agents: the Iliaster and the Archeus. These seem to also be present in each element; the Iliaster, for instance, lies in heaven just like the Vulcanus and the Archeus.Footnote77 Together they work to bring all things to their fruition.Footnote78 The three-fold scheme of the Iliaster, Vulcanus and Archeus may be intentional, complementing Paracelsus’s better-known system of the three principles (tria prima) of sulphur, salt and mercury.Footnote79

In the discussion of the Iliaster and the Archeus, Paracelsus attempts to clarify what he means by these three active agencies. His definitions are both positive and negative: they are not a spirit (Geist), nor a soul, nor a person. What they are is a “nature;” Paracelsus also terms them a “power” (Krafft) and a “virtue” (Virtus); another term is arth, which has also been translated as “nature” or “character.”Footnote80

What is perhaps less clear is how the Vulcanus, the Iliaster and the Archeus may be differentiated. The agent Iliaster is never explained and seems to be quietly dropped post-De meteoris.Footnote81 According to the text, the Archeus is subject to the Vulcanus as a kind of assistant, giving it the instruments that he needs to perform his duties.Footnote82 This concept of a virtue subordinate to another virtue seems to have two reasons.

The first is that it creates a lively picture of nature as containing elementary “laboratories” which resemble the alchemist’s own workshop. The idea of working by oneself in the laboratory seems unfamiliar to Paracelsus; instead, he imagines that a proper workshop would need both a master (the Vulcanus) and assistants (Archeus, and perhaps the Iliaster). This suggests the importance of personal experience in Paracelsus’s formulation of philosophical concepts; while there is no evidence that he worked himself in a workshop, he must have been exposed to the environment enough to make an impression on his thought. The fact that he is associating the hotter Sun with a white colour and the colder Moon with a red colour also suggests an experiential dimension; one is tempted to speculate that he may have seen in the smithy that a white colour in melting metals or minerals denotes a hotter temperature has been achieved.Footnote83 The emphasis Paracelsus places on “experience” will become particularly outspoken in Labyrinthus medicorum errantium, which I will discuss later on in this article.Footnote84

The second reason is that, after 1630, Paracelsus seems keen to organise his work and express it in clearer, less redundant terms. To understand his consolidation effort, we must first review Paracelsus’s prior use of the term Archeus, which seems to be closely related to that of Vulcanus.

An entanglement of concepts: Vulcanus and Archeus

A distant reading of the term Archeus is similarly revealing as in the case of Vulcanus. I began by performing a search for the term Archeus in THEO, which produced 128 occurrences, which I suspected to be an underestimation due to the presence of variants of the word. However, finding the stem of Archeus turned out even more complicated than that of Vulcanus. It seemed reasonable to assume the stem might be “arche;” however, Martin Ruland’s influential Lexicon of Alchemy (Lexicon alchemiae, 1612) also lists Archaeus as a variant,Footnote85 so I had to also account for the possibility of the “archae” stem. Searching for “arche” in THEO, however, yielded a disproportionate amount of results (1904 instances), and replacing this with “archae” made no difference, producing the same list.Footnote86

Moving to Python, I first created a search pattern using Regular Expressions (RegEx) for “arche.”Footnote87 A search for this stem yielded 240 results. However, upon visual inspection, I noticed that the results also included irrelevant results like archelaus and archelai. Concordance confirmed that this word referred to the ancient Greek philosopher Archelaus. Another irrelevant variant proved to be archen (2 occurrences), which was referring to Noah’s ark. Consequently, I accepted 221 RegEx stem results, surprisingly close to the occurrence of Vulcanus and variants in the corpus.Footnote88 By comparison, a search pattern for “archae” yielded only one valid result for archaeus. Examining this occurrence with NLTK concordance and THEO, I found that this term occurred in a minor surgical work.Footnote89 I added this instance to the overall list, resulting in a total of 222 forms of Archeus.

The occurrences of Archeus follow the same pattern as Vulcanus: the predominant term is the nominative Archeus, with 101 mentions, with the vast majority being comprised by the nominative, nominative plural, accusative and dative/ablative Latin forms (). This makes up for an emphatic 87.3% of the total number of mentions, with the more accurate figure being 88.7% if one includes archevs and archaeus in the count.

Concordance shows that, like Vulcanus, the Archeus is referred to by the masculine particle “der”, even though it is also, generally, not conceived as a person ().

A Lexical Dispersion Plot of the terms Archeus and Vulcanus shows that Vulcanus particularly occurs in the first part of the Huser corpus (which tends to cover middle to late writings), while the Archeus is particularly featured in the middle of the corpus (early and middle writings) (). There are however significant overlaps, particularly in vol 2 (late writings), and 8 (the natural philosophical writings), as I will further show.

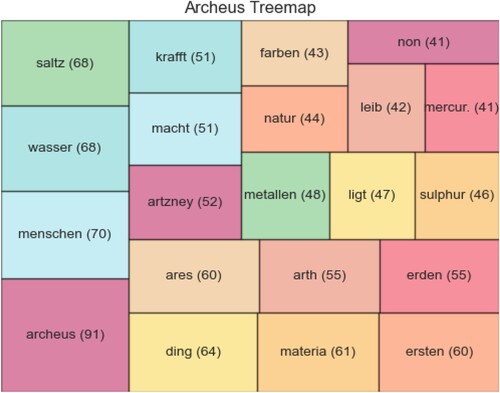

I performed a co-occurrence analysis on Archeus as well, which is useful in comparing and contrasting its use with that of Vulcanus. A visual representation (treemap) of the associations of Archeus is rendered in . Firstly, it reveals that Archeus, like Vulcanus, strongly associates with the word “humans” (menschen), though, interestingly, not the singular “human” (mensch). The imprecise ding appears less here (64 times). Archeus is particularly connected with the element water (wasser, 68 times) and one of the three principles, salt (saltz, 68 times). In fact, the singular ersten (60 times) seems to recall the tria prima; the other two principles, sulphur (46 occurrences) and mercurius (41 times) appear in the top 20 co-occurrences. Thus, the Archeus seems to have a stronger connection than the Vulcanus with the concept of the three principles, one of the most influential notions of Paracelsian doctrine.Footnote90 As in the case of Vulcanus, there are co-occurrences with terms associated with power and activity, though less emphatically so: macht (51 times), arth (55 times), krafft (51 times), natur (44 times). The uncommon term Ares (60 co-occurrences) also seems to denote an active agent, though its precise meaning may need further analysis.Footnote91 Its presence is mainly confined to the period around Basel, appearing in De gradibus, De vita longa and Philosophia de generationibus, but being dropped afterwards. The Archeus is also connected with the element earth, erden (55 times).

Switching to close reading, one of the earliest occurrences of the Archeus is in the Basel work De gradibus & compositionibus receptorum & naturalium (vol. 7). Here, the Archeus seems to be an almighty power which “disposes all” and produces offspring, including the Iliaster.Footnote92 The text, however, is not very easy to follow; the lecture notes that were collected are useful to clarify matters, even as they must be treated carefully. In one of them, the Archeus is described as “that virtue which produces things out of the Iliastes;Footnote93 that is, the dispensator and compositor of all things.”Footnote94 Another note describes it as “disposed Nature, or the disposition of Nature.”Footnote95

It looks as though in De gradibus the Archeus plays the same role as Vulcanus. Yet the notion of Archeus suggests an Aristotelian influence: Aristotle used the term archē to refer to a principle or a first cause. In this sense, it seems more suitable to a school environment, and it is perhaps no surprise that Paracelsus employed it in his Basel lectures.Footnote96

After Basel, Paracelsus continued to make use of the term in Philosophia de generationibus. In this work there is no sign of Vulcanus, with the Archeus occurring 48 times in the text. The Archeus first appears in the second treatise (De salibus), being introduced as “the separator of the Elements.”Footnote97 Yet, while its work would be to separate, its function seems to be in practice more complex: for instance, the Archeus purifies the tria prima and helps procreate metals.Footnote98 Here, again, we have an example of the use of the reproductive metaphor with the Archeus being the male contributor to generation. The activity of the Archeus is more precise here than in De gradibus, being closely connected with alchemical processes of separation, and especially with the mineral and metallic realm. The work of the Archeus resembles that later assigned to the Vulcanus. Yet the Archeus is not related to the heavens here, as the Vulcanus is in De meteoris; its activities remain earthly, being related to the elements of earth and water.

Following Philosophia de generationibus, the Archeus makes a brief and enigmatic appearance in Liber Paragranum (c. 1630, vol. 2) and a more extensive one in Opus Paramirum (vol. 1), more specifically in the distinctive fourth treatise, De matrice.Footnote99 In the latter, the Archeus is called a “smith and a processor” which is found in the human stomach.Footnote100 The mention of the “smith” seems to recall the Vulcanus, except Paracelsus avoids using this term here as elsewhere in De matrice. Yet we were already told in the early Liber paragraphorum that the stomach contains a Vulcanus; here, the Vulcanus is replaced by the Archeus. Vulcanus does appear elsewhere in Opus Paramirum, though it is used chiefly as an adjective denoting the arts of the fire. Yet, for the first time prior to De meteoris, there is a co-occurrence of Archeus and Vulcanus in the same work,Footnote101 albeit in a rather unclear passage:

What counts is rather that the separatio and digestio are so acute and so subtle and fast progressing because of the vulcanic athanori [and because of] the process of the archeus, that a tartarus which goes into the coagulation is broken and turns into water.Footnote102

Vulcanus, Archeus, fire, and alchemy prior to and in Labyrinthus medicorum errantium (1538)

The concept of Vulcanus appears in Die Grosse Wundarztney (1536) and related surgical writings. Here Paracelsus regularly refers to the “art of Vulcanus” or “Vulcanic works.”Footnote103 Vulcanus is described as a laboratory worker (Laborant), which forges and orders things.Footnote104 It seems evidently able to “transmute” as it has within itself the “virtue of transmutation.”Footnote105 The association between Vulcanus and the alchemist is transparent here, yet the concept of Vulcanus reflects De meteoris’s interpretation of it as a power or agency rather than a person. The Vulcanus is present in diseases as a cause of changes in the body, but it is also found in the human stomach. Paracelsus identifies this particular Vulcanus with the Archeus, which possesses the Vulcanic arts of knowing how to destroy what is corporeal. The paragraph is particularly articulate in defining the Archeus and its role in the body:

As is to be understood, there is likewise someone in humans that fulfils the role of these arts, and prepares and completes such separations and destruction of the corporeal. And even though I designate this destroyer of the corporeal with a particular name previously unheard of, as Archeus, no one should wonder at this. For medicine has not yet progressed so far into philosophy, that it would have understood who the destroyer is in nature, or from what foundation the knowledge of illness springs. It is to be noticed that this same Archeus in humans accomplishes all the Vulcanic arts; orders, prepares and shapes all things with the power of the arts given by God to his being (Wesen), each one into its ultimate matter. For that is the ultimate matter, when a thing stands alone in itself, and rejoices in its exaltation, just as does gold, when it is separated from the other two, as has been stated.Footnote106

In the Labyrinthus medicorum errantium, Paracelsus again focuses on the Vulcanus, which is firmly associated with alchemy, as we saw in the introduction: “Alchemy is an art, Vulcanus is its artisan.” The Vulcanus continues to perform the same office as in De meteoris and the surgical writings, as it brings things from their primary matter to the ultimate matter. This transformation is here clearly labelled as alchemy. The ultimate matter is still a type of death, but it is also a necessary death that transforms a being into medicine for the human body. The view of alchemy presented here is firmly anthropocentric:

Wood grows to its end, but not into coals or logs; clay grows, but not into pots: thus it is with all growing things. Therefore the Vulcanus is found in it. Also with an example: God has created iron, but not what can be made from it, that is, horseshoes, iron bars, sickles; only iron ore, and this He gives to us. He then entrusts it to the fire and to the Vulcanus, which is the master of fire.Footnote108

Paracelsus here argues that all things serve the fulfilment of human needs, in line with the Bible. As he explains it, God has created the world and planted “seeds” of future things in it: “God created all things; He created something out of nothing: that something is a seed; this seed gives its end its predestination (Praedestination) and its office (Officij).”Footnote110 Nothing, Paracelsus emphasises, is created as it should be, but everything evolves in time. The process of transformation is undertaken by the agency of the Vulcanus, which makes the seeds bring forth fruit in due course. This is the natural Vulcanus, of course, but there is also an artificial, or human Vulcanus.

In De meteoris, Vulcanus was discussed only in terms of the natural agent in the elements. There was an emphasis on the impersonal nature of this principle. Here, however, the meaning of Vulcanus becomes widened to include human agency. This is a rather surprising development, given Paracelsus’s previous insistence not to treat Vulcanus as a person. One explanation is that Paracelsus may have decided that the difference between active agency and Geiste was no longer relevant. Another explanation would be that Vulcanus is simply seen here as a term denominating alchemical agency – it is a function or, as Paracelsus puts it, an “office” that can be fulfilled by any kind of active agent.

To understand what he means, we should consider the theory he espouses here about the Alchimia Microcosmi.Footnote111 Macrocosmic alchemy happens outside the human body, while the Alchimia Microcosmi is within the body. The two together make up the office or function of the Vulcanus, which, as we now know, is to transform primary matter into ultimate matter.

In De meteoris, Paracelsus had focused on the natural Vulcanus in the heavens and briefly talked about “the Vulcanus of the humans,” by which he meant material fire. Here, however, the Vulcanus denotes the human artisan; as Paracelsus puts it, “he who is Vulcanus has power over the art; he who is not Vulcanus has no power over it at all.”Footnote112 The Vulcanus is here described as both “an apothecary and a laboratory worker (Laborant) of medicine.”Footnote113

The human Vulcanus takes the primary matter and transforms it by an act of separation. It essentially sunders what is useful from what is not so, keeping only the beneficial. Paracelsus’s view here seems to mirror his general theory of poisons, according to which everything has a pure and an impure side, and the role of the alchemist is to extract the medicine and expel the poison.Footnote114 Yet the human Vulcanus is unable to perform the whole office of transforming primary matter into its ultimate one: what she can achieve is only a halfway house. Paracelsus calls this media materia, intermediate matter.Footnote115 The function of this Vulcanus has to be taken up by another Vulcanus, inside the body, which then finishes the process of transformation.

To illustrate this, Paracelsus gives the example of bread.Footnote116 The bread starts off as a seed of grain planted in the earth, which Nature ripens.Footnote117 This seed, he says, is the primary matter. The human Vulcanus takes the grain and makes the bread dough, which she cooks in the oven. The bread thus obtained is the intermediate matter (media materia). A further process is needed to take this intermediate matter into the ultimate one, and that is achieved by microcosmic alchemy. A further Vulcanus, an inner one (der inwendig Vulcanus), lies inside the human stomach; this Paracelsus continues to call by the name Archeus. The Archeus here comes to possess the clear attribute of being an agent in the human stomach. It acts by similar processes to external alchemy to transform the chewed bread into flesh and blood. Thus, the ultimate matter of bread is human flesh.

Consequently, Vulcanus is represented by two agents: the artisan and the Archeus in the body. They are coextensive, and together they make up the function of the Vulcanus. As long as they work together harmoniously, the human being is healthy. When, however, the Archeus in the body for some reason fails and becomes ill, the artisan must step in and compensate. For Paracelsus, there is no real difference between food and medicine; bread is just as much medicine as an elixir. This view allows him to widen the category of the Vulcanus to arts that were not seen as alchemy during the period: the farmer, the miller and the baker, all of whom work to produce bread.Footnote118 The expansion of the category “alchemy” to other arts was already present in Paragranum, where Paracelsus defined alchemy as the perfecting of nature for human use: “For [nature] brings nothing to light that is complete as it stands. Rather, the human being must perfect [its substances]. This completion is called alchimia.”Footnote119 He added that all perfecting arts were alchemy: “For the baker is an alchemist in that he bakes bread: The winemaker in that he makes wine: The weaver in that he makes cloth.”Footnote120 This wide view of alchemy was noted by Pamela Smith, who argued that Paracelsus had been articulated what she termed the “vernacular epistemology” of early modern artisans.Footnote121

Still, in the case of disease, food is insufficient: a stronger alchemy must be performed to yield medicine. Alchemy is however an art that must be learned, because not all medicine actually heals. In his combative style, Paracelsus dismisses the medicine sold by Montpellier apothecaries as a mess (sudelwerck) that fulfils no useful purpose.Footnote122 Instead, proper medicine must come from alchemical processes, which will provide the right remedy that the inner Archeus can digest.

In a further chapter, Paracelsus continues the story by exploring the medical dimension of this alliance between artisan and the Archeus. The characters change somewhat. He now refers to the Vulcanus as the physician. Just as in the case of the Vulcanus, there are two physicians: a human one and an inner one, der inwendig Arzt. The outer physician must cooperate with the inner physician in order to cure a disease inflicting the body. The alchemy of the human physician complements that of the inner one. Yet the art of medicine is also about compensation: intervening when the inner physician becomes weak. The weakness of inner alchemy is explained by the Bible and the power of the Original Sin, which made the human body carry both the seed of destruction and the seed of cure.

Conclusions and methodological reflections

In Labyrinthus medicorum errantium, we encounter a fully fleshed theory of alchemy, which Paracelsus projects as part of his worldview. He does so by universalising the notion of the Vulcanus, which appeared in his early writings and became articulated in his natural philosophical treatise De meteoris. Vulcanus, which was viewed in De meteoris as an impersonal agent of directed change, becomes here an universal operator that could equally be a natural or a human agent. In doing so, Paracelsus manages to blur the boundaries between art and nature, viewing them as co-extensive. This is done by, on one hand, subordinating nature to anthropic purposes, and on the other hand, by recognising the importance of natural agency in human affairs. In doing so, Paracelsus overcomes the clear distinction between art and nature defined by traditional Aristotelian thought.Footnote123 It is true that, in the Labyrinthus, art remains somewhat inferior to nature, just as for Aristotle; the human Vulcanus can only transform primary matter into intermediate matter, not the ultimate one. Yet this inferiority stems from Paracelsus’s religious emphasis on the consequences of the Original Sin, rather than from ancient Greek philosophy.

In turn, Paracelsus’s connection between the human and the natural seems part of a conscious project of uniting natural philosophy, alchemy, and medicine. At the core of it lies a view of matter and change that focuses on generation and death, which is conceptualised in gendered terms. The four elements are macrocosmic wombs that give birth to beings through the intervention of active agents, more often than not seen in male terms. The elements are corporeal, while these active agents have a less clear status. Fire, which is elemental in Philosophia de generationibus but becomes an agent in De meteoris, is fundamentally material. The nature of the other agents (Vulcanus, Archeus, Iliaster) is more elusive; they seem to occupy a liminal place between matter and soul. Even so, they remain closely associated to matter, as shown by co-occurrences of the Vulcanus and the Archeus with matter, the elements and, in the latter case, the three principles.

What is equally remarkable about these agents is their link to alchemy. If the reproductive-generative framework underlies the view of elements and agents, the latter’s activity is closely associated with alchemical enterprises of separating, extracting, and transforming. At the core of these actions lies fire, the material agent, whose role is defined as destructive and corruptive, at least from De meteoris onwards. Yet destruction needs not be the end of a being, which can be brought to a new beginning. This transformation is performed by the master of fire, the Vulcanus, as is emphasised in the Labyrinthus medicorum errantium. Here, Vulcanus employs fire to destroy beings in order to turn them into human food or medicine. We are dealing with a circular process: where the thing being transmuted by fire dies, its death brings about food or medicine for the human body. The circular viewpoint may provide a connecting point between Paracelsus’s philosophy and his religious concerns.Footnote124 For Paracelsus, a similar cycle characterised human history, with the destruction of the world being necessary for the new age to begin.Footnote125

My model began with a close reading of Labyrinthus medicorum, followed by that of Philosophia de generationibus and De meteoris, the latter being mediated by previous scholarship. My analysis was followed by the distant reading of the term Vulcanus, which turned out many loci that were then investigated by close reading. Close reading led to an insight on the connection between the notion of Vulcanus and that of Archeus. This generated a new distant reading, that of Archeus in parallel with Vulcanus. This was naturally followed by a new close reading, and so forth. My experience matched, at first, what Piper described as an iterative spiral that “approaches and yet never quite coincides with some analytical goal.”Footnote126 The inability to zero in on this analytical goal suggests that an infinite number of iterations are theoretically possible. This may be counterintuitive given the finite amount of text at hand; however, the precise meaning of a text remains elusive and warrants delving beyond the analysed corpus into connected writings and historical circumstances. The archive may have no end, just as the search for meaning does not. In practical terms, however, we need to structure this kind of exploration in finite projects, so that we are able to extract meaningful, if provisional, results at various stages of our research.

Furthermore, my experience of hybrid reading has been messier than that depicted by Piper, and this was due to the shifting of the analytical goal in accordance with newly-gained insights. Initially, the analytical goal was defined as understanding the link between Vulcanus, fire and alchemy as came out of Labyrinthus. Soon, however, the analysis had to incorporate the Archeus as a closely-linked term. As I went deeper into the spiral, the wealth of associations between terms denoting active agency became compellingly evident, opening up the possibility of a wider analytical goal, that of understanding Paracelsus’s view of active agents following an evolutionary methodology. As this goal crystallised in my mind, it became apparent that delving further was not feasible within the context of writing one article, so I had to postpone these inquiries for a future study. In that sense, Piper’s iterative computer hermeneutics turned out to be, in fact, closer to a rabbit hole. As all rabbit holes tend to be, it was attractive and difficult to resist. I found there are many possibilities opened up by hybrid readings, in terms of explorations of both corpus and technique. In that sense, this article can be deemed a pilot project that can lead to further exploration.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the special issue editor, Carmen Schmechel, for her careful review and advice throughout the development process of this article. My thanks are also due to the many scholars who have advised or commented on various drafts at the seminars I presented the work at, including the “Natural and Supernatural in Paracelsus” conference at Université de Strasbourg (5–8 June 2023), organised by Urs Leo Gantenbein, Didier Kahn and Andrew Weeks, and the All Souls College Early Modern Intellectual History seminar in Oxford (18 February 2024), organised by Michelle Pfeffer and Noel Malcolm. Special thanks are also due to Gantenbein as well as the anonymous reviewers of this article for advising on parts or all of it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Georgiana D. Hedesan

Georgiana D. Hedesan is Departmental Lecturer in History of Science as well as Lecturer in Digital Scholarship at the University of Oxford. She also works part-time for the TOME project (The Origins of Modern Encyclopaedism, ERC-CZ, 2023–2025), where she deals with the digitisation and exploration of the early modern alchemical corpus. She is a specialist in the history of alchemy and alchemical medicine, and also has a keen interest in computational humanities and their application to the history of science and alchemy in particular. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Paracelsus, Labyrinthus medicorum errantium, in Philippus Theophrastus Bombast von Hohenheim, Paracelsus gennant, Der Bücher und Schrifften des Edlen, Hochgelehrten und Bewehrten Philosophi unnd Medici, Philippi Theophrasti Bombast von Hohenheim, Paracelsus gennant, ed. Johannes Huser, 10 vols. (Basel: 1589), vol. 2, 191–243 (hereafter Labyrinthus) (on 213): “Was das Fewr thut / ist Alchimia, auch in der Kuchen / auch im Ofen.” By “oven” Paracelsus probably means a place endowed with a furnace, perhaps a workshop. Translations are mine unless otherwise noted.

2 Labyrinthus, 212: “Nuhn ist es ein kunst die von nöten ist / und sein muβ: Und so dann in jhr ist die kunst Vulcani, darumb so ist noth zuwissen / was Vulcanus vermag. Alchimia ist ein kunst / Vulcanus ist der Künstler in jhr.”

3 Labyrinthus, 213: “das ist Alchimia, das ist der Schmeltzer / der Vulcanus heist … Was auch das Fewr regirt / das ist Vulcanus.”

4 The distant reading code associated with this work is available at: https://github.com/johedesan/paracelsus_article/

5 I would like to thank Didier Kahn and Urs Leo Gantenbein for providing me with full transcripts of the Huser edition of Paracelsus’s works. The Huser and Sudhoff editions are available for search in THEO – The Paracelsus Database: https://www.paracelsus-project.org/ (accessed 12 January 2024).

6 On Paracelsus’s life, see most recently Bruce Moran, Paracelsus: An Alchemical Life (London: Reaktion, 2019) and Charles Webster, Paracelsus: Medicine, Magic and Mission at the End of Time (New Haven, CT: Yale, 2008).

7 As Gantenbein pointed out, the theological works of Paracelsus pre-date any natural philosophical works; Urs Leo Gantenbein, “The Virgin Mary and the Universal Reformation of Paracelsus,” Daphnis 48 (2020): 4–37.

8 Julian Paulus has helpfully put together a list of Paracelsus’s publications with links to digitised originals: https://www.theatrum-paracelsicum.com/Bibliographia_Paracelsica_Nova_-_Books_by_Paracelsus_1527_to_1599 (accessed 13 Jan 2024).

9 On this treatise, see Didier Kahn, “La Création ex nihilo et la notion d’increatum chez Paracelse,” in De mundi recentioribus phaenomenis: Cosmologie et science dans l’Europe des Temps modernes, XVe-XVIIe siècles, Essais en l’honneur de Miguel Angel Granada, eds. Edouard Mehl and Isabelle Pantin (Turnhout: Brepols, 2022), 207–28.

10 Charles Gunnoe, Thomas Erastus and the Palatinate: A Renaissance Physician in the Second Reformation (Leiden: Brill, 2011), ch. 8.

11 As Gantenbein put it, “In trying to simplify the early modern German spelling, Sudhoff introduced a rather idiosyncratic spelling which often leads to ambiguities. Furthermore, he tried to re-arrange Huser’s order of the writings in order to attain a chronological sequence. However, this attempt appears rather artificial … ” Urs Leo Gantenbein, “The Sudhoff Edition of Paracelsus (1922–1933),” THEO – the Paracelsus Database, https://www.paracelsus-project.org/ (accessed 12 Jan 2024).

12 On this subject see more details in “Paracelsus Project,” THEO – The Paracelsus Database: https://www.paracelsus-project.org/ (accessed 12 Jan 2024).

13 The state of the art on Pseudo-Paracelsianism is given by Pseudo-Paracelsus: Forgery and Early Modern Alchemy, Natural Philosophy and Medicine, eds. Didier Kahn and Hiro Hirai (Leiden: Brill, 2021).

14 Franco Moretti, “Conjectures on World Literature,” New Left Review 1 (2000): 54–68.

15 Margaret Cohen, The Sentimental Education of the Novel (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 23. It might be added that the “great unread” Cohen and Moretti had in mind only regarded fiction novels, itself a small fraction of the published universe. Yet the “great unread” should also account for works left in manuscript, which at least in the case of the history of knowledge are more than those published.

16 Ted Underwood, “A Genealogy of Distant Reading,” Digital Humanities Quarterly 11, no. 2 (2017).

17 An eloquent exponent of the hard view is Andrew Goldstone; see for instance his “Doxa of Reading,” PMLA 132, no. 3 (2017): 636–42.

18 I am not aware of a programmatic articulation of this view, and scholars can position themselves in this camp to various degrees; for instance, Katherine Bode rejects reading but adopts a non-social science approach to distant reading (a term she is otherwise unhappy with), see “The Equivalence of ‘Close’ and ‘Distant’ Reading; or, Toward a New Object for Data-Rich Literary History,” Modern Language Quarterly 78, no. 1 (2017): 76–106. Andrew Piper, on the other hand, adopts the view that distant reading is quantitative but sees distant and close reading as two poles of the same continuum; “Novel Devotions: Conversional Reading, Computational Modeling, and the Modern Novel,” New Literary History 46, no. 1 (2015): 63–98.

19 It is difficult to draw the line between a small and a large corpus. In this article, I deem the Huser Paracelsus a large corpus, comprising 2,314,632 tokens (groups of characters separated by a space). This may be slightly underestimated due to the imperfect process of transforming Word documents (as provided by the transcribing company) into text format.

20 Although many of the techniques used here can be deemed quantitative, my approach has not used word vectorisation. Word vectorisation, or the replacement of words by spatial vectors, is more strongly quantitative, allowing for a variety of measurements and machine learning solutions. I hope to apply such approaches in a future, much larger-scale project.

21 Piper, “Novel Devotions,” 69.

22 On this topic, see Ann Blair, Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010).

23 In his “Genealogy of Distant Reading,” Ted Underwood traced distant reading mainly to the mid-twentieth century, though he mentioned late nineteenth-century attempts as well. However, his definition of distant reading was narrower than mine, referring to the application of strictly quantitative methods in literary study. Interestingly, Mendenhall’s approach, tangentially mentioned by Underwood, was simple word counting; Thomas Corwin Mendenhall, “The Characteristic Curves of Composition,” Science 9, no. 214 (1887): 237–49.

24 Unless the text is born-digital, it requires either manual transcription or the use of an optical character recognition (OCR) tool. OCRs have become increasingly sophisticated, now often based on trained neural networks. Training OCR on historical texts is essential to improving its error rate; see for instance Omri Suissa, Maayan Zhitomirsky-Geffet and Avshalom Elmalech, “Toward a Period-Specific Optimized Neural Network for OCR Error Correction of Historical Hebrew Texts,” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 15, no. 2 (2022): 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1145/3479159

25 The machine-readable corpus of Paracelsus is one initiative that is changing the field; at a grander scale, the NOSCEMUS ERC project has digitised c. 100 million words in history of science, see: https://www.uibk.ac.at/projects/noscemus/. I am currently working on TOME, a Czech government-financed project (PI Petr Pavlas) to digitise Latin alchemical prints between 1500 and 1716, see: https://tome.flu.cas.cz/.

26 Current scholarship generally rejects the systematic approach of one of the most famous scholars of Paracelsus, Walter Pagel, in Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance (Basel: Karger, 1958). Pagel based his analysis mostly on Philosophia ad Athenienses, a treatise whose authenticity was doubted by Sudhoff but marked as possibly authentic by Goldammer; it is now recognised as inauthentic. Pagel did, however, use authentic treatises such as De meteoris in his discussion of prime and ultimate matter and active agents, e.g. Pagel, Paracelsus, 105–06.

27 Reijer Hooykaas, “Die Elementenlehre des Paracelsus,” Janus 39 (1935): 175–87.

28 Dane T. Daniel, “Invisible Wombs: Rethinking Paracelsus’ Concept of Body and Matter,” Ambix 53 (2006): 129–42 (on 133).

29 Didier Kahn, “The Chymistry of Rainbows, Winds, Lightning, Heat and Cold in Paracelsus,” Annals of Science (2024): https://doi.org/10.1080/00033790.2024.2333038, 1–15 (on 3); Didier Kahn, “Paracelsus on the Heavens, Stars and Comments,” in Unifying Heaven and Earth: Essays in the History of Early Cosmology, eds. Miguel A. Granada, Patrick J. Boner and Dario Tessicini (Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona, 2016), 59–116 (on 66, 67).

30 Daniel, “Invisible Wombs,” 134.

31 See Daniel, “Invisible Wombs,” 135; Kahn, “Paracelsus on the Heavens,” 77.

32 On the topic of Paracelsus’s view of gender, see Amy Cislo, Paracelsus’s Theory of Embodiment: Conception and Gestation in Early Modern Europe (London: Routledge, 2010).

33 See Kahn’s extended analysis of this treatise, Kahn, “Paracelsus on the Heavens,” 75–91.

34 For a helpful illustration of this theory, see Kahn’s scheme in “Paracelsus on the Heavens,” 79.

35 Paracelsus, Philosophia de generationibus et fructibus, in Paracelsus, Der Bücher und Schrifften, ed. Huser, vol. 8, 54–159 (hereafter Philosophia de generationibus) (on 67). A scholarly edition and translation of this work as well as De meteoris was carried out by Andrew Weeks and Didier Kahn and is due to appear in print: Paracelsus (Theophrastus Bombast von Hohenheim 1493–1541), Cosmological and Meteorological Writings (Leiden: Brill, 2024).

36 Philosophia de generationibus, 66.

37 Philosophia de generationibus, 66: “Unnd wie das Element Fewr die Erden netzt / unnd ist sein Krafft unnd Eigenschafft; Also zündt es das Holz an / und den Fewrspiegel in der Sonnen.”

38 Philosophia de generationibus, 66.

39 Paracelsus, Liber meteororum or De meteoris, in Paracelsus, Der Bücher und Schrifften, vol. 8, 177–249 (hereafter De meteoris), (on 177–78); Kahn, “Chymistry of Rainbows,” 5.

40 Kahn, “Paracelsus on the Heavens,” 67.

41 De meteoris, 183: “Dann es sagt die Geschrifft / das Gott habe am ersten Himmel vnnd Erden beschaffen / das ist / den Himmel am ersten : Dann vrsach / im Himmel seindt die andern Elementen / in das eusser Elementum Coeli verschlossen”; see also 184.

42 Kahn, “Paracelsus on the Heavens,” 95–96, “Chymistry of Rainbows,” 12–13.

43 De meteoris, 178: “Unnd das ist ein Elementum, das ein Mutter ist der dingen.”

44 De meteoris, 182: “Das Fewr vnnd der Todt seindt gleich: Fewr verzehrts alles unnd nimbst hinweg / also der Todt auch.”

45 De meteoris, 182: “Ignis ist kein Elementum, Coelum ist aber [e]in Element. Ignis ist ein Materia, die do kochet unnd bricht / unnd in die Ultimam Materiam bringet / ist gleich dem Todt.”

46 On the topic of Aristotelian teleology, see for instance John M. Cooper, “Aristotle on Natural Teleology,” in Language and Logos: Studies in Ancient Greek Philosophy Presented to G.E.L. Owen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 197–222.

47 De meteoris, 182: “Darumb so mag Fewr kein Element sein / aber wol ein Todt / ein sichtlicher Todt / ein empflindlicher Todt: So der ander Todt unsichtbar ist / den niemandts sicht noch gesehen hatt.”

48 Paracelsus, Decem Libri Archidoxis, in Paracelsus, Der Bücher und Schrifften, vol. 6, 1–98, (on 7).

49 Alia Scholia in librum secundum De Gradibus, in Paracelsus, Der Bücher und Schrifften, vol, 7, 379–86 (hereafter Alia Scholia), (on 381): “Tristitia, quando quis ad desperationem venit.” I obtained this result by searching for the stem trist* in THEO.

50 De meteoris, 183: “Nemlich das Fewer mags nicht sein : Dann es gibt doch dem Menschen nichts Elementisches / gibt nichts von Früchten / hatt kein gemeinschafft mit dem Menschen / noch der Mensch mit jhm : Sondern so viel vnnd es Todtes Natur antrifft / der da scheidt Seel vnnd Leib von einander. So muß nuhn das vierdte Element der Himmel sein : Dann der Himmel hatt mit dem Menschen gemeinschafft / vnnd der Mensch mag ohn jhn nicht sein / er muß jhn haben.”

51 De meteoris, 183: “Ohn das Fewr mag er [der Mensch] wol sein / vnnd leben ohne das Fewr.”

52 De meteoris, 180: “Nuhn ist er … das Element Fewr / vnd eine Mutter / auß dem das Fewr wachst vnnd entspringet.” See also De meteoris, 183: “das Fewr das ein Element ist / ist der Himmel mit seinen Früchten / das seindt die Sternen.”

53 Such as the disputed treatise De vita longa, which is most likely authentic. In a private communication, Gantenbein informed me that, contrary to the common view, it is becoming clear now that Paracelsus knew Latin and wrote in it; his first works on theology (Mariology) were written first in Latin, but he switched to German in August 1524.

54 The definition of Regular Expressions is “a sequence of characters that forms a search pattern”: https://www.w3schools.com/python/python_regex.asp (accessed 9 January 2024).

55 The nouns are almost always in Latin (vulcanus, vulcani), in various declensions (vulcanus, vulcanum, vulcano), but the adjectives are usually in German: vulcanisch, vulcanischen, vulcanische. To ensure that no mention is missed, and in accordance with best practice in the field, I have lowered all the letters in the Paracelsus corpus. I also tried the possible stem “vulc” and even “vulk” but the results were the same.

56 Vulcanales, vulcanalibus and vulcanalium appear only in Astronomia magna and denote fire spirits. Vulcania and vulcaneis only appear in Alia Scholia (on 380), which is part of the student lecture notes in Basel; here they seem to connote spirits as well, though it is by no means clear where they come from, as the term does not appear in De gradibus itself. On elemental beings in Paracelsus, see Didier Kahn, “La question des êtres élémentaires chez Paracelse,” in Les Confins incertains de la nature, eds. R. Poma, M. Sorokina and N. Weill-Parot (Paris: Vrin, 2021), 213–37; Dane T. Daniel, “Invisible Beings in the Natural World: Paracelsus on Ghosts, Angels, Demons, and Elemental Creatures in the Astronomia Magna,” Nova Acta Paracelsica, N.F. 29 (2021): 89–129.

57 Out of 73 occurrences of the word “vulcanus” in the Paracelsus’s corpus, 37 bear the particle der. There is only one occurrence of the term “das vulcanus” and that appears in the pseudo-Paracelsian Aurora philosophorum.

58 Notably, NLTK does not work with RegEx so I was only able to plot “vulcanus” and not its variants.

59 A more in-depth analysis would be provided by word vectorisation techniques, which would be desirable for the future. In this analysis I excluded words that represent spirits of fire.

60 There are more occurrences of ding than vulcanus variants. Ding is of course not a precise or eloquent word, but its presence is significant for Paracelsus’s language. The usage of the term ding has been noted before; see Webster, Paracelsus, 136; Michael Kuhn, De nomine et vocabulo: Der Begriff der medizinischen Fachsprache und die Krankheitsnamen bei Paracelsus (1493–1541) (Heidelberg: C. Winter, 1996).

61 If mensch and menschen were lemmatised to the common denominator as it is common practice in natural language processing, they would also exceed the number of vulcanus occurrences (in total, 183 occurrences). However, I considered that lemmatising the terms might miss some subtle nuances in Paracelsus’s vocabulary.

62 On the subject, see for instance Pierre Hadot, The Veil of Isis: An Essay on the History of the Idea of Nature, trans. Michael Chase (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), as well as Lorraine Daston and Katherine Park, Wonder and the Order of Nature (New York: Zone Books, 1998).

63 I used the module Squarify, available in Python.

64 Udo Benzenhöfer, Studien zum Frühwerk des Paracelsus im Bereich Medizin und Naturkunde (Münster: Klemm & Oelschläger, 2005), 24. The fundamental work of Karl Sudhoff on the Paracelsus’s corpus remains a point of reference for any scholarly enquiry: Karl Sudhoff, Bibliographia Paracelsica, Versuch einer Kritik der Echtheit der paracelsischen Schriften 1. Teil (Berlin, 1894) and Karl Sudhoff, Versuch einer Kritik der Echtheit der Paracelsischen Schriften 2. Teil: Paracelsus-Handschriften (Berlin, 1898/1899).

65 On this, see Benzenhöfer, Studien zum Frühwerk des Paracelsus, 14–15 and 27.

66 Paracelsus, Priores Quinque Tractatus: Von Farbsuchten in Paracelsus, Der Bücher und Schrifften, vol. 4, 228–34 (hereafter Von Farbsuchten) (on 230): “Nuhn zugleicher weiß wie der Artist in den Metallen Laborirt / vnd sie transformirt in ander farben : Nit allein in Metallen / sondern auch in andern allen Mineralibus. Also ist der Himmel an dem orth der Artist / vnd zu beiden seitten wird gebraucht ein gleichmessig kunst / das ist / Operation : Vnd das der Artist Vulcanum lest das kochen / das ist das Fewrig Element : Also auch der Himmel lest das die Sonn kochen / dann die Sonn ist der Vulcanus im Himmel / der auff der Erden kocht.”

67 Von Farbsuchten, 230: “Vnd das der Artist Vulcanum lest das kochen / das ist das Fewrig Element … ”

68 Paracelsus, Liber paragraphorum, in Paracelsus, Der Bücher und Schrifften, vol. 4 317–418 (hereafter Liber paragraphorum), (on 401): “das Fewr ist gleich als die arth Vulcani : Dann Vulcanus ist nit ein leiblicher Schmid / sondern der Astralisch Fewrmeister / der sein Schmitten führet / vnd vnser Augen sehendts nit.”

69 On the topic, see Pagel, Paracelsus, 37–38, 65–71.

70 Liber paragraphorum, 359: “Dann cibus die heut gessen wirdt / mag vulcanus stomachi nicht digerirn / vnd das beschicht / das der vulcanus Aluminosisch ist. Et haec est causa efficiens dissolutionis.”

71 De meteoris, 204: “der Fabricator vnnd Werckmann aller dingen”; “Derselbige nuhn / der also die ding ordnet von dem Sahmen in sein Vltimam Materiam, derselbige ist Vulcanus.”

72 De meteoris, 204: “Er Componiert / Dispensiert vnnd Ordiniert / die Regen / die Schnee / die Reiff / die Hagel / die Strall / vnnd alles was Himmlische Operationes seind / in denen ist er der Bildschnitzer / der Schmidt vnd Bereitter.” On the importance of meteorology to Paracelsus’s natural philosophy, see Kahn, “Chymistry of Rainbows,” particularly on 2–3, as well as the upcoming edition of the meteorological works, see n. 35.

73 De meteoris, 204-205: “ Dieser Vulcanus ist kein Geist / ist auch nicht ein Person”.

74 On the Pennates and other elementary beings, see Kahn, “Paracelsus’ Ideas on the Heavens,” 97– 99 and Kahn, “Chymistry of Rainbows,” 6.

75 De meteoris, 205: “Ist gleich ein Werckmann als das Fewr / das wircket auch ein jeglichs ding / das in es gelegt wirt : Es schmeltzet die Metallen / es verzehret das Holtz in Glaß / es bereitt auch mancherley / vnd ist kein Geist / ist kein Seel / kein Person : vnd hatt aber in jhme eine solche krafft anzugreiffen / einzugreiffen vnnd zu bereitten wunderbarliche ding : ist der Vulcanus der dem Menschen vnderworffen ist.” While switching between er and es suggests a difference between Vulcanus and fire, at the end of the sentence their identity is postulated.

76 De meteoris, 206: the terms used are “scheiden” (to separate), “außzeuchen” (to take out, extract) or “schmieden” (to forge).

77 A RegEx search on iliaster yields occurrences of the term “iliaster” in the Paracelsus corpus, in various forms (iliaster, yliaster, iliastro, yliastro, iliastrum, yliastrum, yliastrvm, iliastri, yliastri, iliastren, iliastrisch, iliastrischen, iliastriche). Pagel, Paracelsus, 105, understood De meteoris’s Iliaster as being the same as De gradibus’s Iliaster and Iliastes, explaining Iliaster as “a general reservoir of building material” but also as a “hidden power that is inherent in matter in general – ‘primordial matter’”. Yet De gradibus actually differentiates between the Iliaster and the Iliastes, with the former appearing only once in the text as the offspring of the Archeus. The Iliastes is defined in the lecture notes as: “Iliastes est prima materia omnium rerum, constatque & positus est in hisce tribus primis, Sulphure, Sale, & Mercurio : Ex his omnia actum habent,” see Scholia in Libros De Gradibus, in Paracelsus, Der Bücher und Schrifften, vol. 7, 357–73 (hereafter Scholia)(on 357); and “ILIASTES prima mater est omnium rerum, ex qua omnia ortum habent, chaos: Iliastes constat ex Mercurio, Sulphure & Sale,” see In eosdem libros De Gradibus, aliæ quædam breues Observationes, in Paracelsus, Der Bücher und Schrifften, vol. 7, 386–89 (hereafter Observationes) (on 387). Iliastes here is a type of prime matter or hyle, not an active agent. Iliaster, however, as an offspring of the Archeus, seems to be the latter. Yet in Philosophia de generationibus, as Kahn noted, Iliaster changes completely and becomes assimilated to the prima materia, which is also “nothing” (Nichts); Kahn “Paracelsus on the Heavens,” 76–77. In De meteoris, Paracelsus again switches to using the Iliaster as an active agent.

78 De meteoris, 206: “Also wissent auch / das ein Iliaster ist im Firmament / auch ein Archeus, mit sampt dem Firmamentischen Vulcano. Auff das die ding / so der Himmel gebiert / vollkommen geschehen / ist do der Vulcanus, ist do der Iliaster, dergleichen der Archeus, die vollenden jetzt die gantze arbeit biß an jhre statt.”

79 On the three principles of Salt, Mercury and Sulphur, also known as the tria prima, see Kahn, “Paracelsus on the Heavens,” 83–87; Webster, Paracelsus, 132–39; Pagel, Paracelsus, 100–05.

80 De meteoris, 206: “Ist auch kein geschaffener Geist / noch Person / noch Seel / sondern ein Krafft / das ist / ein Virtus die also wircket.” Andrew Weeks in his Paracelsus (Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, 1493–1541): Essential Theoretical Writings (Leiden: Brill, 2008) has translated arth with “nature” (184–85, 192–93, 212–13), but also “spirit” (104–05), “character” (146–47) and “ways” (22627). Overall, arth implies an active aspect.

81 Certainly there are no mentions of the term iliaster in any of its variants in volume 1 and 2 or 10 (Astronomia magna).

82 De meteoris, 206: “das ist / gibt Vulcano terrae sein Instrumenten / sein Zeug zu seiner notturfft.”

83 My thanks to the special issue editor Carmen Schmechel, for pointing this out.

84 On Paracelsus’s notion of experience, see also Pamela Smith, The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 87–89.

85 Martin Ruland, Lexicon alchemiae (Frankfurt: Palthenius, 1612), 52.

86 Unrelated terms like “Artzet” and “starcker” were caught up in the results.

87 A strict search into the stem “arche” can give misleading results, as it includes non-relevant terms like “archelaus” and gives too many occurrences (357 instances). I have adjusted the RegEx to eliminate those stems that included the letter “l”, reducing the mentions to 223.

88 Again, the nouns are in Latin (archeus, archei, archeo, archeum); adjectives are used less, but also in Germanised form: archeisch, archeischen, archeischer.