ABSTRACT

While the link between navigation and astronomy is quite evident and its history has been extensively explored, the prognosticatory element included in astronomical knowledge has been almost completely left out. In the early modern world, the science of the stars also included prognostication known today as astrology. Together with astronomical learning, navigation also included astrology as a means to predict the success of a journey. This connection, however, has never been adequately researched. This paper makes the first broad study of the tradition of astrology in navigation as well as its role in early modern globalization. It shows how astrological doctrine had its own tools for nautical prognostication. These could be used when dealing with the uncertainty of reaching the desired destination, to inquire about the condition of a loved one, or an important cargo. It was widely used, both in time and geographical context, by navigators and cosmographers for weather forecasting and elections for the start of a successful voyage.

1. Introduction

In 1494, the new king of Portugal, Manuel I, concerned with the feasibility of a sea journey to India, summoned to the court the Jewish astrologer Abraham Zacuto. The king asked for the astrologer’s advice on whether it was possible to accomplish such a maritime feat. After pondering the question, Zacuto told the king that not only would the enterprise be successful because he was under a powerful and beneficial planetary influence, but it would also be accomplished very soon by two Portuguese brothers whom the astrologer could not name. This tale is found in Lendas da India by Gaspar Correia, opening the account of how Manuel I endorsed and was successful in establishing the first European sea voyage to India.Footnote1 The later date of this text and the fact that this meeting was held in secret brings its reliability into question, but Damião de Gois, the official chronicler of Manuel I, confirms this practice by the king. He states that the king was very fond of astrology and asked for astrological judgements on the departure and return of ships to and from India from the astrologer Diogo Mendes Vizinho, and later from his physician Tomás de Torres.Footnote2 It is commonly assumed that mention of astrology in the chronicles is made just to embroider a decision or a person’s reputation.Footnote3 However, in the case of King Manuel I the evidence strongly suggests that his maritime enterprises were assisted by astrological advice.

In chronicles of this kind there are many other references to navigators, cosmographers, and even pilots as being astrologers. The term ‘astrologer’ can be problematic in this period given that until very late in the seventeenth century the words astronomy and astrology were interchangeable. Often the exact meaning can only be derived from context, but there are many instances where the use of the word is unclear. Yet, historians of science should not assume that astrology means just astronomy and not astrology as well; in fact, it might mean both in this period. It is often clear in chronicles that it was assumed that an astrologer would be knowledgeable about both. Such is the case of Rui Faleiro and Andrés de San Martín who were involved in the planning of Magellan’s famous expedition of 1519-1522.Footnote4 Fernão Lopez de Castanheda in História do descobrimento e conquista da Índia mentions that Andrés de San Martin was summoned to see if he could find the location of the Moluccas by astrological means.Footnote5

Because the estimating of latitude and longitude is mathematical and astronomical in nature, it is immediately assumed that astrology here means what it is called astronomy today – which is likely the case here. Yet, the way it is phrased casts some doubts. It could also mean the use of astrology to prognosticate on the accomplishment of the enterprise, in the same manner as King Manuel I did regarding the journey to India. In fact, the notion that astrology was used in Magellan’s voyage is frequently implied, and commonly stated as a fact, in the Décadas da Ásia by João de Barros. For example, he states that San Martin had not properly calculated the time of the departure, strongly suggesting that he was expected to select an auspicious time for the beginning of the journey by means of astrology.Footnote6 The death of Magellan as well as his own showed that he had not chosen well: ‘The time and place of their deaths was not grasped by the astrologer Andrés de San Martin, despite that, from the ascendant of their departure and some interrogations that Ferdinand Magellan had made to him, he foresaw a great danger of death from that voyage.’Footnote7 Barros’ statement makes clear that this is beyond choosing the best tide since this would not have repercussions on the general outcome of the enterprise. Here he is referring to two common practices of astrology: (1) elections, which are the choosing of a favourable moment to begin an enterprise; and (2) interrogations, which are made by judging the astrological chart for the moment a specific question is asked.

The same use of astrology is clearly asserted at other times. When faced with the need to find land, Barros claims that Magellan asked San Martín to forecast by means of interrogations, since ‘having failed with measurement and navigation, leaving aside astronomy, he turned to astrology’.Footnote8 After the ship, San António, mutinied and returned to Spain, Barros states that ‘Magellan, wishing to know what had happened to her, asked the astrologer Andrés de San Martin to prognosticate it from the time of her departure and his interrogation.’Footnote9 This describes the use of an astrological chart for the departure of the ship as well as a chart for the moment the interrogation was made by Magellan to the astrologer. Given that the event took place in the Strait of Magellan, this is likely to be one of the first accounts of astrology being practised in the southern hemisphere, with all the computations required to cast an astrological chart for these high southern latitudes. The episode is corroborated in a document recording the questioning of two Spanish sailors from the Magellan expedition at the Portuguese fortress in Malacca.Footnote10 They state that when the ship disappeared it was presumed that the pilot Estevão Gomes had turned against the captain, Álvaro de Mesquita, Magellan’s cousin. This assumption, according to the two sailors, was due to ‘a judgement that an astrologer made there by order of Ferdinand Magellan’.Footnote11

Even considering the often-biased nature of these accounts, the persistent references to astrology in accounts of voyages, shows this to be a common, well-known practice in this period. The very imposition by the Church of the external artificial division of navigation as one of the three sanctioned uses of astrology further reinforces this perception. However, despite the vast historiography on navigation this subject appears never to have been touched upon, except perhaps very lightly. A more attentive view on this matter shows a widespread connection between astrological prognostication and maritime enterprises for the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Using as sources the literary narrative of chronicles and the more pragmatic content in almanacs, astrology books, inquisition processes, and treatises on navigation, two approaches to astrology and navigation emerge. The first was applied to navigation-related matters having a wider range and popular use (i.e. used also by non-navigators). It included inquiries into the success and profit of a journey, news from ships and their return, and the status of sailors or travellers. It could also employ the election of a good moment for the launching of a ship, or the beginning of a voyage. These elections could also be applied to the second approach. This would be the use of astrology for the very act of navigation and the planning of the journey by navigators. This internalist use was considered a more scientific (i.e. natural) approach to the matter and involved mainly weather forecasting by means of astrology.

The importance of the use of astrology in navigation – in particular this second approach – is evident in the long-standing criticism of astrology by the Church in the early modern period. In the second half of the sixteenth century, in the wake of the Counter-Reformation and the Council of Trent, a series of prohibitions were put into place against astrology. First, in 1564 by the well-known Rule IX of the Index, prohibiting the possession of books on the so-called superstitious forms of astrology.Footnote12 The rule limited the publication of astrology texts to those that did not infringe on the premises of free-will and chance events. The bull Coeli et Terrae, issued in 1586 by Sixtus V, restricted even further the practice of astrology in Catholic territories. It extended the prohibition to the practice of astrology, which should not forecast anything that went against free will, even if stated as a mere possibility.Footnote13 Both these documents restricted the practice of astrology to three areas: agriculture, navigation, and medicine. This concept was not new, and it was rooted in late antiquity and mediaeval Christian writings. Augustine, a key author on the matters of the licit and illicit uses of astrology, confirms that astrological judgements on storms and serenity of air (i.e. weather forecasting used for navigation), health and sickness of the body (medicine), and abundance and barrenness of the harvest (agriculture) are licit. This style of phrasing would become common in both pro- and anti-astrology texts. Another later and important author, Thomas Aquinas, refers to the common – and implicitly licit – observations of the Sun and Moon made by farmers, seamen, and physicians, again implying these same divisions.Footnote14

General historiography has accepted these three headings of agriculture, medicine, and navigation as just others of many anti-astrology regulations of this period. However, this tripartite division had a considerable impact on the early modern practice of astrology. First, it carried the powerful authority of the Catholic Church. Secondly, it made it more scientifically acceptable. The use of astrology could be justified by natural causes only within these fields, well grounded in accepted Aristotelian natural philosophy and morally sound for a Christian practitioner. Any prognostication in these areas would not infringe on free will or chance events and was not subject to censorship by the Church. All other practices, comprising most of the common usages of astrology, would be considered superstitious and therefore illicit. These included such matters as marriage, career, children, and wealth.Footnote15

This direct intervention by the Church in the practice of astrology profoundly shaped its use in Catholic countries. It had lasting repercussions not only at a philosophical level, but also in the type of materials being published.Footnote16 This also extended to the core doctrine of astrology which was later noticeably modified to accommodate their concept of natural astrology.Footnote17

The inclusion of medicine among the licit practices of astrology is unsurprising; medical practice had a well-known connection to astrology and much has been researched and written on the topic.Footnote18 It was extensively used to diagnose diseases, to elect the suitable time for a medical or surgical intervention, and many substances, foods, and plants had an Aristotelian-astrological classification to accommodate celestial correlations. Should this use of astrology be forbidden, it would cripple core medical practices of this period. Furthermore, medical astrology was based – for the most part – on the natural influences of the celestial bodies on the human body, and thus was considered a licit practice.Footnote19

When it comes to the subjects of agriculture and navigation, their relationship is not as straightforward. Anyone familiar with classical and mediaeval astrological practices and texts might find this emphasis strange. The oddness comes not from the application of astrology to the topics themselves, but to their choice as the main headings where astrology was permitted. Both agriculture and navigation are for the most part based on natural phenomena and are obviously licit, thus it is expected that the same would be true of most applications of astrology to them. But this does not clarify what astrological practices are being considered regarding these two subjects. In contrast to what might be assumed by simply reading the bull, astrology was divided not into these three topics, but into four large areas of application, known as the four divisions or branches of astrology. The first is usually named revolutions of the years of the world (more commonly, revolutions, and sometimes mundane astrology). It deals with the astrological prognostication of natural, social, and political events. The second, nativities, genitures, or birth charts, deals with the individual. The third and fourth, already discussed above, were interrogations (also known as questions or, later, horary), addressing direct enquiries on specific matters, and elections, the choosing of favourable moments to engage in a particular task.

Considering these divisions within the astrological literature, the topics of agriculture and navigation are rarely featured by themselves in most astrological treatises. They usually appear as subheadings under the four divisions, most commonly in astrological elections or interrogations as emphasized in the examples above, and in the case of agriculture also in revolutions when addressing the plentifulness or scarcity of crops for a given year or season. One evident correlation of agriculture and navigation with astrology could be the almanacs. This popular and widely circulated genre of printed books featured several prognostications and useful information and advice on weather, crops, tides, and other such phenomena, some even including medical information and tables.Footnote20 Yet, almanacs are only the popular face of astrology. Its practice presented a greater level of complexity, far beyond simple tables of phenomena and the modest – if often naïve – monthly and yearly prognostications of almanacs. The field of navigation, much in the same manner as medicine, was a specialist practice requiring far more knowledge than that found in a mere almanac, thus its connection to astrology would be more complex than simple tables of tides and lunations.Footnote21

2. Astrological doctrine on navigation

A central question in this paper is what exactly is meant by navigation where astrology is concerned, since this connection is often assumed lightly and with no proper evidence. First must be considered the position of navigation within the early modern map of knowledge. Navigation was part of the same group of mathematical practices as astrology since it had a direct connection to astronomy. And so, in the same way that mathematics and astronomy comprised most of the theoretical support for the practice of navigation, astrology too was supported by astronomical computation. In this sense both were the practical applications of mathematics and astronomy, to which were then added the sailing expertise of the navigator and the interpretative skill of the astrologer. Thus, beyond mathematics, both disciplines had their own particular doctrines and canons derived from practical application. Secondly, astrology was applied to all manner of human activity from the simple act of buying clothes to the foundation of a city, or the enthronement of a monarch. Considering the examples discussed above, astrological doctrine and interpretation was also applied to the various activities involving navigation. Additionally, given the type of restrictions put in place by the bull it becomes evident that the use of astrology in navigation, in a similar fashion to medicine, was not only a common practice, but also one important enough to be exempt from prohibition, otherwise it would not be worth mentioning it in the regulations. Yet, the technical dimension of this practice is a matter that remains nearly untouched by researchers, being only partially addressed in a handful of papers.Footnote22 So it becomes important to examine in what way navigation is present in astrological doctrine.

Because astrology had a wide application to all human activities, each of the foundational interpretative principles used for astrological judgement – the seven planets, the twelve zodiacal signs, and the celestial houses – was encoded with certain correlations to specific activities.Footnote23 Navigation and nautical matters were no exception. These correlations were commonly called significations, and a planet, a house, or a sign was said to signify an activity, a profession, an object, certain types of people, colours, tastes, substances, etc. Most of these correlations date from classical and mediaeval texts. However, most of the voyages of this period in the European context were not oceanic. Considering this earlier tradition the present study will give particular attention to the early modern astrological texts since by this period navigation is taking place in a global context, and more widely and more frequently than at any other moment in history.

To begin it must be noted that there are several simpler correlations concerning nautical matters that can be commonly found in most astrological books. These set the scene for more complex and specialized doctrines on navigation. The Moon is perhaps the most straightforward of these correlations because of its obvious connection to tides. It is commonly associated with sailors, fisherman, coastal areas, harbours, and docks.Footnote24 Regarding the zodiacal signs, Cancer, ruled by the Moon, is associated with the sea, great rivers, and any navigable waters.Footnote25 Capricorn, represented by a sea goat, is commonly associated with sails, ropes, and storehouses for naval materials.Footnote26 The system of the twelve houses, in which astrological judgement is rooted, includes two houses related to travel. The third house representing short distance travel, usually by land, and the ninth house corresponding to long distance travel particularly by water.Footnote27 There are other less common astrological techniques in an early modern context that might be applied to maritime matters, such as the Lot of Travel on Water, used to assess the benefit resulting from journeys by sea.Footnote28

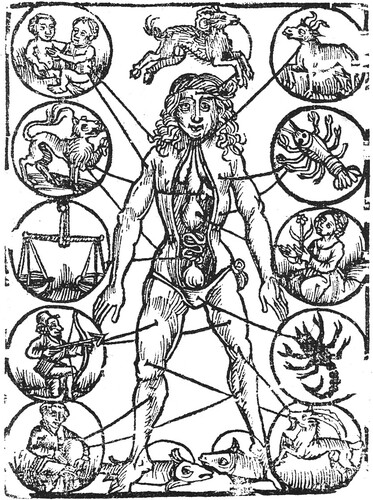

Beyond these principles, there are more noteworthy associations to navigation in the astrological doctrine. The first originates from a well-known astrological concept: the melothesic, or astrological man. In this scheme, fundamental to astrological medicine, each part of the body corresponds to a zodiacal sign, used to identify potential illnesses in an individual, or to select the more propitious moments to intervene in that area of the body medically or surgically. As with most astrological doctrine it had its origins in antiquity and it was commonly known. Numerous almanacs and books provided the correspondences in pictorial form as shown in : Aries, the head; Taurus, the neck and throat; Gemini, the arms; Cancer, the chest; Leo, the heart and back; Virgo, the belly; Libra, the bladder and kidneys; Scorpio, the genitals; Sagittarius, the thighs; Capricorn, the knees; Aquarius, the legs; Pisces, the feet.

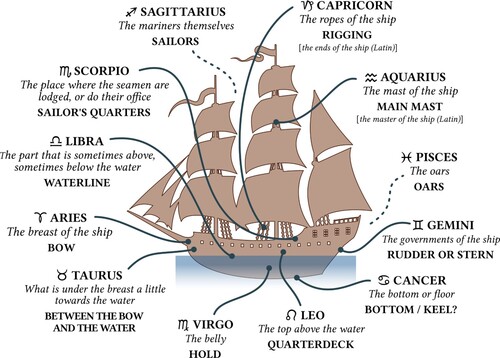

There is, however, a lesser-known, but similar, scheme that attributes each sign to a part of the ship creating a melothesic ship. The only other such scheme known to exist is that relating to equine health which could be included in the agricultural part.Footnote29 The common version circulating in seventeenth-century books is taken from the eleventh-century Tunisian astrologer Haly Abenragel (Abū l-Ḥasan ‘Alī ibn Abī l-Rijāl al-Shaybani). His Complete Book on the Judgements of the Stars was a major source for sixteenth- and seventeenth-century practitioners because of its comprehensive explanations of all divisions of astrology.Footnote30 The correlation is as follows:Footnote31 to Aries is attributed ‘the breast of ship’, meaning the bow; to Taurus ‘what is under the breast a little towards the water’; to Gemini ‘the governments of the ship’, the rudder or stern; to Cancer ‘the bottom or floor’, perhaps including the keel; to Leo ‘the top, above the water’, possibly the quarterdeck; to Virgo ‘the belly’, corresponding to the ship’s hold; to Libra ‘the part that sometimes is above, sometimes below the water’, that is the waterline; to Scorpio ‘the place where the seamen are lodged, or do their office’, the crew’s quarters; to Sagittarius ‘the mariners themselves’, that is the crew; to Capricorn ‘the rigging of the ship’, but ‘the ends of the ship’ in early modern versions; to Aquarius ‘the mast’ originally, but ‘the master of the ship’ in early modern versions; to Pisces ‘the oars’ (see ).Footnote32 There are some variations of these attributions from antiquity to the Middle Ages, which are discussed in detail by Pérez Jiménez, but this paper will focus on the early modern version.Footnote33

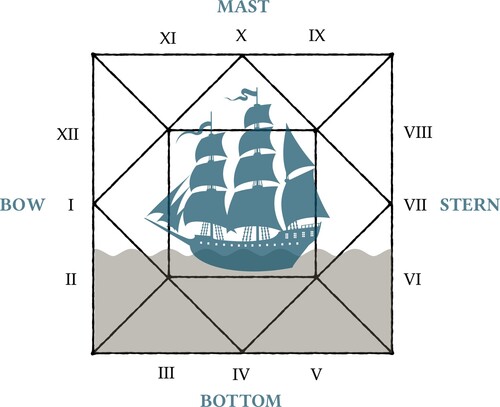

An alternative was the use of the houses to produce an equivalent interpretation. Here the so-called angular houses would represent the four main parts of the ship: bow (ascendant/first house), stern (descendant/seventh house), mast (midheaven/tenth house), and bottom (angle of earth/fourth house). The houses below the horizon would represent the parts of the ship under or close to water, while those above the horizon, the parts above the water (see ).Footnote34 These methodologies were applied in interrogations, such as in an inquiry on the state of a ship undergoing a journey, or in elections, such as the beginning of an important journey. The presence of malefic planets or configurations in these signs would signify damage to the associated area of the ship.

3. Applying astrology to nautical matters

As seen in the cases of Manuel I and Magellan, there appears to have been a wide-ranging use of astrology by kings and navigators to secure the success of their travels. But what was the full range of its use? Given the scarcity of this type of source the current historiography, this study uses a number of examples of nautical astrology ranging from the above-mentioned early sixteenth-century Portuguese and Spanish voyages to mid-seventeenth-century English shipping and early eighteen-century texts on navigation. However, this same diversity of dates and geographies provides a strong case for the continuity and global reach of nautical astrology in the early modern period.

Two types of practices have been evidenced in the above examples: interrogations and elections. Interrogations, due to their utility, appear to have been a common astrological practice in the early modern period. The Iberian context is no exception, but the use of interrogations was seen as illicit by the Catholic Church. Any question about a future outcome, or an unknown past event was seen as infringing free will, or worse, revealing secret and hidden knowledge that could only be obtained through demonic intervention and not by natural means. Thus, interrogations had to be used with great caution.

The case of Portugal is still scarcely studied. However, Inquisition proceedings against astrologers have provided valuable evidence of this practice. One of the richest examples is the case of Lisbon-based astrologer, Manuel Rodrigues, who was summoned by the Inquisition in 1583.Footnote35 In the trial transcriptions are detailed various types of enquiries made by Rodrigues’ clients. These included questions about marriages, lost objects, missing persons, and of especial relevance for this study, questions referring to the success of a voyage, and on the status and wellbeing of those currently at sea.Footnote36 The most detailed example of the latter in Rodrigues’ trial is that of Domingas Lopes, wife of Manuel Fernandes. She came to the astrologer to ask about her husband who was sailing to India and if he was healthy and well-liked by all. Rodrigues asked for a few details about her husband and told her to return for the answer in two days’ time. However, she never got the answer, since she told her confessor about the consultation and he advised her not to return.Footnote37

Similar practices are also reported in the Spanish context both in popular settings, as in Rodrigues’ case, and at court. In the latter case, cosmographers were often called to advise on political matters by means of astrology. For example, Juan Bautista Gesio who worked for Felipe II of Spain,Footnote38 or the Portuguese cosmographer, Juan Baptista Lavanha, who calculated the nativity of King Sebastian, and later worked for the Spanish crown.Footnote39 The astrological activities at the popular level are once more described in Spanish Inquisition records. Such is the case of physicians who, beyond the accepted purposes of medicine, also used astrology for prognostication on thefts, marriages, and missing persons.Footnote40

Inquisition hearings also document astrological practices by navigators and other nautical experts. In 1616, an edict against astrology was issued by the Inquisition of Mexico. After its reading at Manila’s cathedral, the cosmographers and navigators Juan Segura, Alonso Flores, Juan de Cevicós, and Hernando de los Ríos were called to the Inquisition. As with Rodrigues in Lisbon, among the reasons for their being summoned were testimonies that their practice of astrology included the prohibited interpretation of nativities and answering questions about lost and stolen objects.Footnote41 Yet, nothing appears to have resulted from these proceedings. During his testimony Alonso Flores also denounced António Moreno and Diego Ramírez de Arellano, cosmographers at the Casa de la Contratación, as being knowledgeable of judicial astrology.Footnote42 The Casa de la Contratación had apparently some role in the transmission of astrology to this class of experts by offering some level of astrological training.Footnote43

This use of astrology extended as well to the exploration of the New World. Pedro Porter Casanate, sailor and explorer of California, is a good example. He is mentioned in the well-known Inquisition trial of Mexican bookseller and astrologer, Melchor Pérez de Soto.Footnote44 Porter Casanate had apparently taught astrology to Pérez de Soto, and according to a witness the two men had met to elect the time of departure for Porter Casanate’s journey to explore California.Footnote45

Unfortunately, despite the above evidence of its common use, astrological documents with detailed examples of interrogations in both Portuguese and Spanish contexts – especially regarding nautical matters – are, as far as can be ascertained, still unknown.Footnote46 The presence of the Inquisition early in the sixteenth century, combined with a lack of systematic research on Portuguese and other Iberian astrological manuscript materials, might explain this absence. Comprehensive examples of such practice can be found in the surviving notebooks and writings of Protestant astrologers, particularly in England where many of these materials were either published or preserved in archives. A good example comes from the famous English astrologer William Lilly. In his book Christian Astrology (1647) he demonstrates this by studying the question ‘A ship at Sea in What Condition’.Footnote47 In his judgement of this interrogation he considers several factors, that the Moon, significator of the ship, because it is the ruler of the ascendant degree, was unfortunate because it was departing from a hard square aspect with the malefic planet Saturn, here a significator of death due to its rulership over the eighth house.Footnote48 At the end he states that: ‘Principal significators under the Earth, ill: worst of all, if in the fourth, for that is an assured testimony of sinking the Ship’. Therefore, the significators were below the horizon in a chart, i.e. below water, and in a weakened and afflicted condition, furthering the conclusion that the worst had happened. Interestingly, the question was posed by a merchant who was waiting for a shipment of goods. Lilly judges that the chart also shows a great loss of property due to the difficult configurations involving the significators of wealth: the second house and the Lot of Fortune. Given other similar examples, this kind of interrogation seems to have been common practice for those with money invested in shipments. Lilly himself offers a second example in Christian Astrology, ‘A Ship at sea if lost’ (pp. 162–64), where a merchant was concerned regarding the delay of a ship he had sent to trade on the coast of Spain. Different from the above, Lilly judged that the ship was damaged in a storm but it would return. Several other judgements of this type are presented by his contemporary, John Gadbury, as will be discussed below.

The other application of astrology to navigation was the election of astrologically favourable moments. This was usually done for the departure of a ship. However, according to astrological doctrine this could be applied to other significant events surrounding a ship and its history, including its construction. These are well explained by Haly Abenragel in book seven of the Complete Book, dedicated to elections. In the chapter on journeys by water:

Know that in journeys by water and in entering in the ships there is great mastery and use of roots of the elections. (…) Because this we said on the beginning of the building of the ship is one root. And the second root is of the time of its purchase. And the third the time in which is launched to water, and this is a powerful root. The fourth is the time in which men enter it. And the fifth is when the ship is set in motion; this is also a very powerful root. And all these roots are to be kept.Footnote49

He defines five important moments in the history of the ship in the same manner as the conception and birth charts are used for people.Footnote50 Although the full application of this methodology may have remained theoretical, this is a matter that still requires research. Given the widespread use of astrology and the money involved in shipping and commerce in any pre-modern period in history, it would not be a surprise to find that this would be more commonly applied. In some cases, an astrological chart would be erected for the building and purchasing of a ship as instructed by Haly Abenragel, on which the astrologer would prognosticate on the durability of a ship and the success of a journey. In the subsequent chapters, Haly explained the rules for entering the ship, and launching it. This doctrine had a long tradition in astrology books, with Dorotheus of Sidon being one of the earliest sources to provide these rules.Footnote51 The existence of such a complex doctrine (long present in the Greek sources), with meticulous rules and canons applied to nautical matters for elections, is a strong indicator that the application of astrology to navigation was a significant proportion of the practice.Footnote52

Once more, in the Iberian context, astrological manuscripts with detailed examples of elections have yet to surface. However, it is clear in the abovementioned chronicles that this was a regular practice. Good examples of this are the requests by King Manuel I for astrologers to judge the departure of ships to India, the discussion surrounding the miscalculation of the time of departure of the Magellan expedition, and the beginning of Porter Casanate’s exploration of California.

Once more, detailed demonstrations of this practice come from much later Protestant sources. A showcase of this and other uses of astrology for seafaring can be found in a book published by another well-known British astrologer, John Gadbury. Entitled Nauticum Astrologicum or the Astrological Seaman, it was published in 1691 and reprinted in 1697 (under the title, Ἀστρολογοναύτης), and posthumously in 1710.Footnote53 In the text, Gadbury collects the essential knowledge of nautical astrology providing forty examples of its use. This monograph appears to be unique in focusing entirely on nautical matters, whereas in other texts they always appear among other applications of astrology. The book is divided into four parts or chapters, the first contains a summary of the astrological principles, the second explains the differences between elections and questions, the third lays out the astrological rules to use in navigation, and the fourth offers various examples of their use. Gadbury divides the latter into three sections, one with charts of the launching of ships (which he calls ‘nativities of ships’), and another with election charts. The third focuses on interrogations about people and ships lost at sea (). At the very end, Gadbury adds several pages with a diary of the weather for the years 1668 and 1689. Despite its later date, this work is quite relevant, because of its summarization and exemplification of the use of astrology in sea travels. On the cover, Gadbury states that this work will advise mariners and captains of ships, but also merchants, and, quite interestingly, insurers. The latter topic is common in the section on questions with four cases where the delay of a ship encouraged the merchant to consider insuring his cargo.Footnote54 An example is the question ‘a Barbados ship, if best to ensure’ in which Gadbury judges the ship to be safe and advises against insuring. but the client, ‘not much crediting Judicial Astrology’ took out the insurance and lost his money.Footnote55

Table 1. List of charts in Nauticum Astrologicum.

Seafaring matters are also discussed in other divisions of astrology such as that of human nativities. In this case, it would be in a general sense and less about navigation itself: if journeys are a good or bad thing for the native; the choice of favourable places to travel to; or one’s suitability for maritime-related trades.Footnote56

An interesting example of such an application is that of Portuguese royal physician Aires Vaz. He faced prosecution because of an astrological report for the year 1539 that he had presented to King João III. One of his predictions concerned navigation, although indirectly. According to Aires, in a previous report for 1538 he had predicted a revolt in India and when the news about it would arrive. This had come true since later that year Diu came under attack by the Ottoman Empire.Footnote57 In the new report, Aires told the king that soon news would arrive from India of his success. Again, this was apparently correct since the Ottomans were defeated and the siege broken. This is a good example of how important it was to anticipate these events and when news would arrive. In this case, the methodology was neither interrogations nor elections, but that of the king’s birth chart. This was done by applying commonly used methods of forecasting in natal charts, one of which is called revolutions of the years of nativities.Footnote58 Apparently, Aires Vaz predicted the conflict based on a conjunction of Saturn and Mars in the king’s 1538 revolution.Footnote59 This shows how the nativity of the king could be a crucial element for prognostication, a fact that is also hinted at in the case of King Manuel I when the astrologer refers to his being under a beneficial configuration.

It was, however, in the division called revolutions of the year of the world, also known as mundane astrology, where the much more skilful application of astrology relevant to navigation had its place: weather forecasting or astrometeorology, which will be dealt with next.

4. The navigator-astrologer

The use of interrogations and elections in nautical matters did not require the astrologer to have any expertise in navigation. Practitioners such as Manuel Rodrigues or William Lilly offered their judgements only as experts in astrological interpretation, but it is still unclear how frequently it was used among experts in navigation. Was it restricted to these two fields as shown by the case in Manila, or was there a more specialized application? Given all the above testimonies involving navigators and cosmographers, interrogations and elections appear to be quite common. However, a more specialized and erudite form of nautical astrology can be found in navigation texts.

Diego Pérez de Mesa was the chair of mathematics in the Complutense and Seville universities (1586–1595 and 1595–1600, respectively). He wrote several texts on mathematics and cosmography, including navigation and astrology.Footnote60 One large treatise on astrology ‘Tratado de Astrologia’, preserved in MSS 5995 of Biblioteca Nacional de España, includes chapters on the computation and rectification of an astrological chart, on the foundations of astrology, on nativities, and on elections.Footnote61 The text offers only one chapter related to navigation in the section on elections (‘De la Nauegacion’), where he is quite straightforward on his views:

Knowingly I leave here [aside] those unfounded disputations of the Arabs on the fabrication of ships and their launching into water, and this I only warn – which was what Pindar said – that the duty of the good sailor is to know of the storm three days before it comes. The obvious signs of storm are: the conjunction of the Moon and Mars, or with fixed stars of its nature and has its rise or setting with Arcturus, the herdsman, of Orion, of the goats, [since] these stars cause each year very large storms; in the same manner observe where Saturn is and if the closest conjunction or opposition of the luminaries prognosticates storms.Footnote62

There are several instances in the treatise where astrology is discussed. The first, and perhaps the most noteworthy is in part one, in the chapter ‘On Storms and violent movement of the sea’ (‘De Las tormentas y mouimento violento del mar’). Here Pérez de Mesa begins by introducing the reader to the various types of movement according to Aristotelian philosophy, proceeding with the movement of the waters, and then connecting it to the movement of the celestial bodies. This movement could be known (1) by means of the relations between the constellations and the movement and change of the winds (i.e. astrometeorology), (2) by the movement of the sea itself, (3) by weather indications, which imply the abovementioned changes in the clouds, sky, as well as the behaviour of animals:

Thus, the knowledge of this motion [of the waters], or storms, will be taken from three parts. The first of the efficient universal cause, I mean from the constellations, because these are those that mainly move and change the winds which cause the shaking of the water and make its restless. The second of the matter, meaning [the substance of] the sea itself. The third of certain astrological [or meteorological]Footnote66 indicators that appear in the elements and the mixed, both animate and inanimate, to which Ptolemy calls second stars.Footnote67

Regarding the first part, the navigator astrologer can see the disposition of the heavens or celestial figure at the beginning of the year, or ingress of the Sun in Aries, well examined by perfect mathematical observation, or by the doctrine of King Afonso of which we have a satisfactory experience. [Also] the quarter of the year in which the navigation will take place, taking note if it falls under a period or domain of an eclipse, examining, thus, the figure of said eclipse (…)Footnote68

Likewise, following the doctrine of Ptolemy, the navigator astrologer, can see the disposition of the heavens in the conjunctions, and oppositions, and quarters of the Sun and Moon; and if in them he finds one of the aforementioned constellations, within that month or period of the Moon, or within that quarter he may fear storms or winds … Footnote69

After describing the general conditions that are typical for each region or coast, depending on the time of the year, he moves to more particular forecasting. He discusses the custom of waiting for the fourth or fifth day after the new moon, or the second day after the quarter. He states that these rules might be enough for the rustic and ignorant because they often seem to work. However, when greater precision is needed, other astrological events would have to be taken into account. It is in such complexities that the skill of the astrologer navigator is required. For example, certain planetary configurations observed in the charts of lunations could be easily contradicted by stronger ones, such as eclipses or aspects of the Moon to the superior planets:

These [weather prognostications] can only be made by the true knowledge of the constellations and movement of the stars [as] natural causes, because from them depend the natural variation and changes of the weather. And if the pilots say that there is a moment of serenity and wind because the configuration that causes it is well established, they will be in danger from their own belief, because this configuration can change immediately after their departure and change the weather, and they will not be aware of this by their ignorance of this configuration and its movement. (…)Footnote70

It is therefore convenient for the perfect navigator to know astrology, and that he observes not only the signification of the season and the month with its almutens, but also the: quarters [of the Moon]; aspects, conjunctions and oppositions that the superior planets make with each other and with the Sun; the eclipses, their effects and the time when they start, and when they initiate other effects, and the setting of the main fixed stars, and all other diligences that the astrologers make.Footnote71

And this is why Sixtus V, in the bull he made against superstitious divinations (and all the ancient fathers and the whole Church) knows and declares that astrology is necessary for navigation among other things.Footnote72

This focus on astrometeorology applied to navigation is not an idea exclusive to Pérez de Mesa. A similar approach can be observed in the work of the Portuguese cosmographer António de Najera. Although he never states this connection as clearly as Pérez de Mesa, his writings show the same emphasis on navigation and astrology. He produced two major treatises: one on navigation and another on astrometeorology, the same two subjects highlighted by Pérez de Mesa. The text on navigation, Theoretical and practical navigation (‘Navegacion especulativa y pratica’) published in 1628, unlike Pérez de Mesa’s has few references to astrology. The use of astrology is only briefly mentioned relating to the forecasting of the winds, ‘To which, without a doubt assists, the meeting of the celestial bodies by conjunctions and aspects which by their influences also move the winds, as the astrologers state.’Footnote73 A few years later, in 1632, Najera published a comprehensive treatise on astrometeorology, Astrological summation and art to teach how to prognosticate the weather (‘Summa astrologica y arte para enseñar hazer pronosticos de los tiempos’). Differently from Pérez de Mesa’s text, this book is not focused on the sea or navigation, but explains the entire doctrine of astrological meteorology in detail. He refers to navigation in the prologue when discussing the usefulness of this knowledge to the many areas of human endeavour, listing agriculture and medical activities as well:

For I noted all these difficulties knowing how important it is to use in the good government of a republic, the correct knowledge of the weather for the easiness of the ploughing of fields, of the sowing of seeds, the planting of trees, the breeding of domestic animals in the service of Man, and furthermore, for the navigation and commerce on the seas, by electing the days in which the stars with their influences show favourable winds for navigations and temperate days, healthy for land travel, as also to elect convenient days for the medication of the sick. And finally for the many human actions preformed at the appropriate times that can be known by the influxes of the Stars by who well and correctly apprehends this science of the weather and changes of the air.Footnote74

A similar type of text to those of Pérez de Mesa and Najera is also found in the English Protestant context, and again under the name Gadbury. Not John Gadbury, but his paternal uncle Timothy Gadbury (born circa 1624).Footnote75 Very little is known of this author and his life besides his few publications. In 1656, together with his nephew, he published an updated edition of the tables of fixed stars by George Hartgill, which served as the Gadburys’ introduction to notable English astrologers of the period.Footnote76 A few years afterwards, in 1659, Timothy Gadbury, as sole author, published a text linking astrology and navigation, The young sea-man’s guide, or, The mariners almanack.Footnote77 This text was re-edited with a few modifications in the following year when he also published a pamphlet with a judgement of the nativity of Charles II.Footnote78 After these publications Timothy Gadbury is no longer heard of, despite the continuous popularity of his nephew’s almanacs.

The young sea-man’s guide is quite different from the usual mariners’ almanacs as well as the standard almanacs of the year. Its purpose is to offer a summarized manual of astrometeorology adapted to the needs of the seaman. These are proper astrological teachings and not just signs of changes in the weather adduced from the visual appearance of the Sun or Moon more frequently listed in this kind of publication. Thus, the book begins with the foundations of astrological doctrine, followed by instruction in the judgement of the winds, and then of the weather. The 1659 guide also offers an ephemeris with data of the year’s eclipses and the astrological figure of the Aries ingress, followed by a table of houses, thus providing the basic material needed for the calculation of an astrological figure. The next edition of 1660 contains the same doctrine as in 1659 but without the ephemeris, adding instead a list of ships, a table of wages of officers and sailors serving the king, a calendar, and a table of the Moon’s latitude. In both instances the guide ends with advertisements for new books and instruments for the trade. With little over a hundred pages, the doctrine presented in the book is quite comprehensive, albeit concise, explaining concepts that most almanacs do not. The astrometeorological doctrine is tailored to seafaring but necessarily abridged with Gadbury stating that it is not ‘his task at present to treat of the weather, however, to further the young learner I shall willingly adde a word or two in general thereof, with a table’.Footnote79 Some of the material presented is quite similar in detail to that presented by Pérez de Mesa, but Gadbury focused mostly on the winds and their prognostication based on lunations, conjunctions of the Sun with the fixed stars, the Aries ingress (which he exemplifies), the qualities of constellations, and the nature of the planets. At the end, he reiterates the importance of the ingresses and their previous lunations and eclipses for the prognostication of weather redirecting the reader to Haly Abenragel’s text, and the works by thirteenth-century astrologers Guido Bonatti, and Leopold of Austria, commonly consulted by astrologers. Despite its more popular target and smaller size, Gadbury’s guide shows how widespread this connection of astrological weather forecasting to navigation was in global culture, continuing the trend observed in the works of Pérez de Mesa and Najera and evidenced in the teachings of the Jesuit colleges.

From all the above, it can be established that the application of astrology to nautical matters encompasses three areas: weather forecasting, elections, and interrogations. Protestant astrologers would make use of all three, but no Catholic astrologers would endorse – at least publicly – the use of interrogations, especially by the seventeenth century when the Inquisition rules were already well established. Their use by King Manuel I, by the cosmographer Andrés de San Martín, or by an ordinary astrologer such as Manuel Rodrigues date from period before the papal bull of 1586; and the case of the Manila cosmographers in the aftermath of its implementation in New Spain. However, elections could safely be applied to natural matters such as navigation, thus, weather forecasts and elections would be the two practices sanctioned for use in navigation in a Catholic context.

Cosmographers such as Pérez de Mesa or Najera present a more erudite or scientifically inclined discourse and seem to leave aside elections completely (and obviously, interrogations). Pérez de Mesa clearly discards elections for shipbuilding and launches as Arabic delusions but advises on the election of a favourable departure. At first sight, the latter seem to be only weather related, yet, his astrological text includes applications of astrology that in the eyes of the Inquisition would be marginally, if not completely, illicit. António Najera does not mention elections, but he is mentioned in Inquisition proceedings as owning forbidden books on judicial astrology.Footnote80 So, neither of them was a stranger to these practices. It is unclear if they really thought that elections and questions were not valid astrological practices in maritime situations, or if they were simply being cautious because of the Inquisition. Considering their use by other cosmographers, as seen above, the latter might well be the case.

There are, however, Christian authors where these two aspects of nautical astrology appear together. Between 1707 and 1715 the Spanish mathematician Tomás Vicente Tosca published a large compendium covering all mathematical topics.Footnote81 Tome nine, treatise XXVIII, is dedicated to astrology offering (1) the foundations of astrology, (2) prognostication on weather, agriculture, navigation, and medicine, (3) prognostication on nativities, and (4) a criticism of the claims of astrology.Footnote82 As expected for an author of this period, Vicente Tosca is very critical of many astrological doctrines especially those concerning nativities. Nonetheless, he adopts its use in the matters of weather and navigation, discussing it in book two. Following the same doctrines as Pérez de Mesa and Najera, he explains in detail the canons of astrometeorology (chapters one to eight). Additionally, in chapter nine he offers a series of aphorisms for navigation. Tosca starts by instructing the reader to observe the lunations around the time of the journey to be sure the weather will be good, as suggested by Pérez de Mesa. Then he enters fully into the domain of astrological elections, offering several rules relating to favourable and unfavourable configurations for starting a sea journey much more akin to those of usual astrological elections:

To begin the journey search for the time when at the orient rises a water sign, except the scorpion. Or when the Moon is found in a water sign with Jupiter or Venus, or with a trine or sextile aspect from these planets. And that neither the ascendant nor the Moon be in aspect with Saturn or Mars. The Sun in the ascendant, or [in conjunction] with the Moon, as well as its aspects of opposition or square are considered harmful. Also harmful is [the conjunction of] the ascendant or the Moon with tempestuous stars, as are the Pleiades, Hyades, Orion, Arcturus, Antares, Aldebaran, Hercules, Delphinus, Argo Navis, Canis Major and Minor, Capella. The malefic planets should not rule over the ascendant, as well as the Moon, if they have no beneficial aspect of Jupiter. At the time of navigation, the Moon should be in signs that are the dignity of benefic planets and with some aspect to them. Likewise, should be sought that the Moon is above the Earth, and if below, in the third or fifth house. The planets with rule over the ascendant and in the place of the Moon, should be benefics, be well placed in an angle, free of bad aspects and assisted by good ones. And specially they should not be in the sixth, eighth, or twelfth houses, nor retrograde or with retrograde planets.Footnote83

5. Determining the undetermined, anticipating the future

In the pre-modern world astrology was by definition knowledge that allowed the prediction of future events. So, it is not surprising that astrology would be a valuable tool when facing all the vicissitudes of any long journey by sea. The evidence presented here is enough to conclude that astrology had indeed an extensive role in early modern navigation; unsurprising since astrology had been applied to this task since antiquity. Its doctrine included the methodologies for investigating the success of a sea journey, the quality of the weather, and even less licit procedures for ascertaining the whereabouts or status of a ship. For the early modern mind astrology could be used to predict the possible outcomes and unexpected obstacles of a long voyage, as it did for many other human activities. As such, navigation became one of its enduring and sanctioned uses. Despite the suspicion of the Church and increasing challenges to its validity, this use continued at least until the early eighteenth century.

These astrological methods were engaged at two different levels. The first, can be classified as external to the doctrine and practice of navigation, and more popular in its scope and application. It dealt mostly with the day-to-day requests of the astrologer’s client, such as questions about the arrival of a ship, the condition of someone travelling by sea, or the success of a journey for business. This level did not require of the astrologer any expertise in matters of navigation beyond common knowledge. This is well testified in the activities of most of the abovementioned astrologers and demonstrated in the example by William Lilly.

The other sphere of engagement was more internalist and used by the navigator astrologer. It was practised by those working in navigation and included the mariner’s knowledge of the sea. This practice was more mathematical in nature and grounded in natural causes. At its core were the astrological weather forecasts for a safe journey at sea, and the adjustment of the departure time according to these estimations. This practice could also be applied by a well-educated astrologer since the doctrine was the same and as can be seen in many almanacs. However, almanacs would rarely reach the level of complexity or detailed day-to-day weather prognostication suggested by Pérez de Mesa. They targeted a wider readership, offering only a general yearly or seasonal forecast. Pérez de Mesa presented astrological weather forecasting in a specialized manner, focused on the needs of the practising navigator. A general analysis of the year required between four to eight astrological charts including the four seasonal ingresses and the four preceding lunations, to which were added the charts of any visible eclipses. The complex use of astrometeorology, as intended by experts in navigation, required much more, since it required day-to-day observations. This necessitated not only a good knowledge of astrology, but also astronomical and mathematical skills to make the necessary computations and adjust them for the required coordinates. Such practical mathematical expertise would have to be learnt in maritime institutions such as Casa de la Contratación, but more research is needed to discover the size of the role of astrology in such institutions. The Jesuits, via learning centres such as the College of Santo Antão in Lisbon, provided exactly the same level of astronomical and astrological knowledge together with lessons in navigation.

Sometimes these distinctions are not straightforward since there were areas where these two levels overlapped. Elections could also be used to assist in preparing for navigation, especially in choosing the time for a ship’s departure. This choice could be either related to weather, as observed in Pérez de Mesa, or based on a more orthodox application of the astrological doctrine for elections, such as that presented by Tosca or Gadbury. Interrogations could also be used by the navigators, as seen in the case of Andrés de San Martín, but these were illicit for Catholics, so discretion was needed.

No matter if permitted or forbidden, popular or erudite, the above examples show a wide range of uses for astrology in matters related to navigation and nautical activities. Further research is needed and numbers of practitioners assessed before a full picture of this subject can be created, but there is sufficient evidence to encourage further study. The connection of astrology with navigation promises many fascinating avenues for exploration that encompass various aspects of early modern life. From navigation planning and teaching to the social and human impact of long journeys and absences, as well as commercial practices and insurance. All performed to attempt to offset the many hazards involved in the global voyages of the early modern era.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the useful suggestions by the peer reviewers, express my gratitude to Professor Henrique Leitão for his support, early revision and comments on the paper, to my team members at the Rutter project for their feedback, and in particular to thank José Maria Moreno Madrid's valuable advice on some of the sources used.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Gaspar Correia, Lendas da Índia, ed. by Manuel Lopes de Almeida (Porto: Lello & Irmão Editores, 1975), I, p. 10.

2 ‘Foi muito dado à Astrologia judiçiaria, em tanto que no partir das naos pera ha India, ou no tempo que has speraua, mandaua tirar juizos per hum grande Astrologo Portugues, morador em Lisboa, per nome Diogo Mendez Vezinho, natural de Couilhã, dalcunha ho coxo, porque ho era daleijam, e depois deste faleçer com Thomas de Torres seu physico, homem mui experto, assi na Astrologia, quomo em outras sciençias’ – Damião de Góis, Crónica do Felicissimo Rei D. Manuel, ed. by Joaquim Martins Teixeira de Carvalho and David Lopes (Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 1926), iv, pp. 201–02. Diogo Mendes Vizinho, also called José Vizinho, is known for his astronomical activities which include the publication of the Almanach Perpetuum (1496), containing the astronomical tables by Zacuto.

3 For a study of the use of astrology in the Portuguese chronicles, see Helena Avelar de Carvalho, ‘Vir Sapiens Dominabitur Astris: Astrological Knowledge and Practices in the Portuguese Medieval Court (King João I to King Afonso V)’ (Universidade Nova de Lisboa – Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, 2011).

4 Discussed at length in João de Barros, Decada terceira da Asia de João de Barros. Dos feitos que os portugueses fezerão no descobrimento & conquista dos mares & terras do Oriente, 3 vols (Lisboa: impressa per Jorge Rodriguez aa custa de Antonio Gonçalvez mercador de livros, 1628), III, chap. 6. A first exploration of the role of astrology in the work of Andrés de San Martín was made by Leonardo Ariel Carrió Cataldi, ‘Astrología a Bordo: Andrés de San Martín y El Viaje de Magallanes’, Anais de História de Além-Mar, XX (2019), 121–44.

5 ‘& mandou coele a hum astrologo chamado Andrés de Sam Martim, pera que por astrologia visse se podia alcançar a saber a altura de leste a oeste de que se esperaua muyto dajudar pera ho dereito deste descobrimento’ – Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, História do descobrimento & conquista da India pelos portugueses (Coimbra: João Barreira, 1554), VI, p. 6 (chapter 6).

6 ‘Mas parece que também este não calculous bem a hora do dia que a armada partio de São Lucar de Barrameda que foi a vinte & hum dias de Settembro do anno de quinhentos & dezanoue, pois não vio como elle & Fernão de Magalhães auião de acabar na ilha de Subo’ – Barros, III, fol. 141r.

7 ‘O qual tempo & lugar de suas mortes não alcançou o astrologo Andres de San Martin: posto que pelo ascendente de sua partida, & por algumas interrogações que lhe Fernão de Magalhães fezera, elle lhe tiha ditto que naquelle caminho lhe via hum grande perigo de morte’ – Barros, III, fol. 145r. Barros also states that Ruy Faleiro could have predicted an ill end to the journey and chose not to go (fol. 141r).

8 ‘porque desejando achar alguma terra firme, & fazendo interrogações sobre isso ao astrólogo Andres de San Martin, porque como lhe já falecia a conta & razão do marear, leixando a Astronomia, couertiase á Astrologia.’ – Barros, III, fol. 145r.

9 ‘Fernão de Magalhães desejando saber o que era feito della, disse ao astrologo Andres de San Martin que prognosticasse, pela ora da partida & sua interrogação’ – Barros, III, fol. 143r.

10 Lisboa, Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (ANTT), Corpo Cronológico, Parte II, mç. 101, n.o 87.

11 ‘e dali desapareçeu a nao de que era capitam Alvaro de Mezquita e a presunçam em todo sera que o piloto Estevam Gommez portugues prendera ao dito capitam e tornava em busca de Joham de Cartagena e do creligo e que esta presunçam era por hum juizo que hum estrolico hy tirou por mandado do dicto Fernam de Magalhaes’ – ANTT, Corpo Cronológico, Parte II, mç. 101, n.o 87, fol. 3r.

12 ‘All books and writings on geomancy, hydromancy, aeromancy, pyromancy, onomancy, chiromancy, necromancy, or those in which are contained the drawing of lots, sorceries, auguries, auspices, incantations of the magic art, are entirely rejected. But let the bishops see carefully that books, treatises, indices on judicial astrology be not read or kept, which dare to affirm as certain that something is to happen regarding future contingent, or chance events, or those actions dependent on the human will. However, judgments and natural observations which are written for the purpose of aiding navigation, agriculture, or the medical art, are allowed.’ These and other documents are reproduced in Ugo Baldini and Leen Spruit, Catholic Church and Modern Science: Documents from the Archives of the Roman Congregations of the Holy Office and the Index. Volume I. Sixteenth-Century Documents (Roma: Libreria editrice vaticana, 2009), I, pp. 160–67.

13 ‘by this constitution that shall be forever valid, we establish and command by virtue of our apostolic authority that against the Astrologers, Mathematici, and any others who from now on practice the aforementioned art (except in regard to agriculture, navigation or medicine), or cast judgments and nativities of men in which they dare to state something will happen regarding future occurrences, successes and chance happenings, or acts dependent upon human will – even if they say or protest that such a thing is not stated as a certainty.’ – Sixtus V, ‘Contra exercentes artem astrologiae judiciariae’, in Magnum bullarium Romanum, a Pio Quarto usque ad Innocentium IX, ed. by Angelo Cherubini (Lovain: sumptib. Philippi Borde, Laur. Arnaud, et Cl. Rigaud, 1655), II, pp. 515–17 (p. 516 (section 3)).

14 As noted by H Darrel Rutkin, Sapientia Astrologica: Astrology, Magic and Natural Knowledge, ca. 1250–1800: I. Medieval Structures (1250–1500): Conceptual, Institutional, Socio-Political, Theologico-Religious and Cultural, Archimedes (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019), p. 197.

15 This does not mean that such applications did not continue to be used. They were practised privately in Catholic countries, as attested by some manuscript evidence, and openly in many Protestant countries.

16 For example, the popular Ephemeris published by the mathematician Giovanni Antonio Magini in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, offered an introduction to astrology which in later editions, after the papal bull, is replaced by texts on astrology for use in agriculture, navigation, and weather forecasting.

17 An example is the excising of the significations of the twelve houses. See Luís Campos Ribeiro, ‘Transgressing Boundaries? Jesuits, Astrology and Culture in Portugal (1590–1759)’ (unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Lisbon, 2021), pp. 387–92 <http://hdl.handle.net/10451/49744>.

18 See, for example, Lauren Kassell, Medicine and Magic in Elizabethan London: Simon Forman: Astrologer, Alchemist, and Physician (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Astro-Medicine: Astrology and Medicine, East and West, ed. by Anna Akasoy, Charles Burnett, and Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim, Micrologus’ Library, 25 (Firenze: SISMEL Edizioni del galluzzo, 2008).

19 This would not accommodate any medical practice that made use of talismans and other magically based cures that could be associated with astrology. See: Mark A. Waddell, Magic, Science, and Religion in Early Modern Europe, 1st edn (Cambridge University Press, 2021), pp. 88–89.

20 On almanacs and their history see, among others, Bernard Capp, Astrology and the Popular Press: English Almanacs 1500–1800 (London: Faber, 1979); William E. Burns, ‘Astrology and Politics in Seventeenth-Century England: King James II and the Almanac Men’, The Seventeenth Century, 20.2 (2005), 242–53; Louise Hill Curth, English Almanacs, Astrology and Popular Medicine, 1550–1700 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007); Luís Miguel Carolino, A escrita celeste: almanaques astrológicos em Portugal nos séculos XVII e XVIII, Memória & saber (Rio de Janeiro: Access, 2002); Elide Casali, Le Spie Del Cielo: Oroscopi, Lunari e Almanacchi Nell’Italia Moderna, Biblioteca Einaudi 158 (Torino: Einaudi, 2003); Justin Rivest, ‘Printing and Astrology in Early Modem France: Vernacular Almanac-Prognostications, 1497–1555’ (MA dissertation, Ottawa, Carleton University, 2004).

21 Following the same argument, and although farming schedules and advice could be considered under the larger topic of agriculture, its proper connection to astrology is in dire need of further exploration, however the present paper will deal only with navigation.

22 Namely Gilbert Dagron and Jean Rougé, ‘Trois horoscopes de voyages en mer (5e siècle après J.-C.)’, Revue des études byzantines, 40.1 (1982), 117–33; Joanna Komorowska, ‘Seamanship, Sea-Travel and Nautical Astrology: Demetrius, “Rhetorius” and Naval Prognostication’, Eos, 88 (2001), 245–56; Aurelio Pérez Jiménez, ‘Dodecatropos, Zodíaco y Partes de la Nave en la Astrología Antigua’, MHNH, 7 (2007), 217–36; and some aspects of astrological symbolism and navigation are also addressed in Wolfgang Hübner, Raum, Zeit Und Soziales Rollenspiel Der Vier Kardinalpunkte in Der Antiken Katarchenhoroskopie, Beiträge Zur Altertumskunde, Bd. 194 (München: Saur, 2003).

23 In this period the seven planets in the astrological sense of ‘errant stars’ are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, as well as the Sun and the Moon.

24 William Lilly's Christian Astrology is usually a good source for the common early modern correlations, but many others could be used such as Dorotheus of Sidon, Alcabitius, Guido Bonatti, to name just a few. William Lilly, Christian Astrology Modestly Treated in Three Books, 1st edn (London: Tho. Brudenelle, 1647), p. 82.

25 Ibid., p. 94.

26 Ibid., p. 98.

27 Ibid., pp. 52 and 55.

28 Abū Maʿšar, The Great Introduction to Astrology, ed. by Keiji Yamamoto and Charles Burnett, 2 vols (Leiden: Brill, 2019), I, p. 889. The lots or parts are mathematical computations used for very specific subjects and are calculated taking the distance between two points in the chart (commonly planets) and projecting it from a third point (usually the ascendant degree). This lot is taken by day from Saturn to 15° of Cancer and cast from the ascendant (reversed in nocturnal charts). The lots gradually fell out of favour in seventeenth-century astrology.

29 Examples of the zodiacal horse can be found in New York, Morgan Library, MS M.735 fol. 62r, and in Martín Arredondo, Obras de Albeyteria: primera, segunda y tercera parte (Madrid: por Bernardo de Villadiego, 1669), p. 170. On this representation see also Josefina Planas Badenas, ‘El caballo astrológico en el tratado de albeitería de Manuel Díez’, Goya: Revista de arte, 340 (2012), 187–99.

30 El libro complido en los iudicios de las estrelas, more widespread in his Latin translation, Preclarissimus liber completus in iudiciis astrorum, which had multiple editions.

31 ‘Da el signo de Aries a los pechos de la naue, e Tauro a aquello que es so los pechos un poco escontra el agua, e Gemini a los gouernios de la naue, e Cancer al fondon de la naue, Leon al somo de la naue, aquello que esta sobre la agua, Virgo al uientre de la naue, Libra a lo ques alça e se abaxa de los pechos de la naue en el agua, Scorpion al logar o esta el marinero, Sagitario al mismo marinero, Caprico(r)nio a las sogas que son en la naue, Aquario al maste de la naue, Piscis a los rimos.’:ʻAlī Abū al-Ḥasan al-šaybānī Ibn Abī al-Riǧāl, El libro conplido en los iudizios de las estrellas, ed. by Gerold Hilty (Madrid: Real Academia Española, 1954), p. 128; for an English early modern version, see William Lilly, Christian Astrology, pp. 157–58.

32 In William Lilly and other English early modern astrological authors, Capricorn is listed as ‘the ends of the ship’. This appears to be an error of the Latin translation where the word ‘finibus’ replaces the original Spanish ‘sogas’, ropes or rigging. This misreading of the Latin ‘funibus’ which appears in manuscript versions such as that of Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Cod. Guelf. 12.7 Aug. 2°, fol. 91v. As to Aquarius, Lilly, and others list ‘The master or captain of the ship’, possibly a mistranslation of the Spanish ‘maste’ to the Latin ‘magister’, and consequently ‘master’ in English.

33 Pérez Jiménez.

34 See al-Riǧāl, p. 128. For a discussion on the sources and variations of this method, see Pérez Jiménez, pp. 218–21. A more detailed study of these attributions, their transmission, and translation is being currently researched by Juan Acevedo and Luís Ribeiro (forthcoming in Rutter Technical Notes: <https://rutter-project.org/technical-notes/>).

35 Lisboa, Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (ANTT), Tribunal do Santo Ofício, Inquisição de Lisboa, proc. 7544.

36 ANTT, Tribunal do Santo Ofício, Inquisição de Lisboa, proc. 7544, fol. 18v: ‘e quem quer navegar lhe pergunta se sucederá bem a viagem’; fol. 19v, ‘pessoas que navegam se sam vivos ou mortos.’ Other mentions are in fols. 35v, 40r-41r, 49r.

37 ANTT, Tribunal do Santo Ofício, Inquisição de Lisboa, proc. 7544, fols. 15v–16r.

38 Tayra Lanuza Navarro, ‘Astrología, Ciencia y Sociedad En La España de Los Austrias’ (Universitat de València, 2005), pp. 154–59.

39 Lisboa, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal. Cod. 887, fol. 1r.

40 For a study of these cases see Adelina Sarrión Mora, Médicos e inquisición en el siglo XVII (Cuenca: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 2006), pp. 86–103.

41 Ana Cecilia Ávalos Flores, ‘Cosmografía y astrología en Manila: una red intelectual en el mundo colonial ibérico’, Memoria y Sociedad, 13.27 (2009), 27–40 (pp. 34–37).

42 John Newsome Crossley, Hernando de Los Ríos Coronel and the Spanish Philippines in the Golden Age (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013), pp. 147–49.

43 Tayra Lanuza Navarro, ‘Astrology in Spanish Early Modern Institutions of Learning’, in Beyond Borders: Fresh Perspectives in History of Science, ed. by Josep Simon and others (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2008), pp. 79–103 (pp. 84–88).

44 The case of Pérez de Soto case as a bookseller and book owner is well documented although few studies focus the details of his astrological practices. See: Donald G. Castanien, ‘The Mexican Inquisition Censors a Private Library, 1655’, Hispanic American Historical Review, 34 (1954), 374–92; Ana Avalos, ‘As Above, So Below. Astrology and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century New Spain’ (unpublished PhD thesis, European University Institute, 2007), pp. 211–35; Alejandra Isabel Ledezma Peralta, ‘Contrabando de libros prohibidos en la Nueva España (1650–1700): el caso de Melchor Pérez de Soto’ (unpublished MA dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, Facultad de Filosofía, 2018).

45 Ávalos Flores, p. 37.

46 As also referred to by Lanuza Navarro, ‘Astrología, Ciencia y Sociedad En La España de Los Austrias’, p. 136. There are, however, more documents containing nativities, especially for noblemen and women. Judgements of the year, eclipses, and comets are more common due to their status as natural astrology. A few examples of interrogations seem to exist in Inquisition records, but these have not been catalogued. See, for example, Sarrión Mora, pp. 89–90.

47 Lilly, Christian Astrology Modestly Treated in Three Books, pp. 165–66.

48 In an astrological judgment of this kind, the first house (which begins at the ascending zodiacal degree at the eastern horizon) represents the ship. It is at 6° of Cancer, a sign said to be ruled by the Moon, so it becomes the significator of the ship. A square aspect (i.e., an angular relationship of 90°) is said to afflict a planet, especially if from a malefic planet such as Saturn, as is the case. Since Saturn rules the eighth house of death (because the house begins at 26° of Capricorn, ruled by said planet), its meaning is considered to be even more destructive, leading to a bleak answer.

49 ‘Sabias que (en) as carreiras por agua (e en) entrar enas naves á mester grande guarda e seguir as raizes das eleiçoes. (…) Pois que isto dissemos de comegamento de fazer a nave é ua raiz. E a segunda raiz a ora que a conpran. E a terceira raiz a ora que a meten ena agua, esta é apoderada raiz. E a quarta é a ora que entra en ela omen. E a quinta raiz é a ora que moove a nave, esta outrossi é muito apoderada raiz. E todas estas raizes son de guardar.’ – Abu-’l-Ḥasan ʻAlī Ibn-Abī-’r-Riǧāl, El libro conplido en los iudizios de las estrellas: partes 6 a 8: trad. hecha en la corte de Alfonso el Sabio, trans. by Gerold Hilty (Zaragoza: Inst. de Estudios Islámicos y del Oriente Próximo, 2005), p. 149.

50 When studying a birth it was usual to consider the time of that birth and the nativity or natal chart arising from that time. The conception chart, sometimes used alongside the natal, was derived from a method known as the Trutine of Hermes or Mora.

51 David Pingree, Dorothei Sidonii. Carmen astrologicum (Leipzig: Teubner, 1976), p. Book V, Chapters 23–25, 281–86; or in another version Dorotheus of Sidon, Carmen Astrologicum: The ’Umar al-Tabari Translation, trans. by Benjamin N. Dykes, 2nd edn (Minneapolis: Cazimi Press, 2019), p. Book V, Chapters 24–26. Dorotheus’ text is one the major sources for astrological doctrine because of its practical approach to astrology which contrasted with Ptolemy’s theoretical discussion of astrology.

52 On these earlier sources and applications, see: Dagron and Rougé; Komorowska; Pérez Jiménez.

53 John Gadbury, Nauticum Astrologicum or, the Astrological Seaman; Directing Merchants, Marriners, Captains of Ships, Ensurers, &c. How (by Gods Blessing). They May Escape Divers Dangers Which Commonly Happen in the Ocean· Unto Which Is Added a Diary of the Weather for XXI. Years Together, Exactly Observed in London, with Sundry Observations Thereon. (London: printed for Matthew Street, 1691), p. [8], 245, [11]p. :; the other editions are: Ἀστρολογοναύτης or, The Astrological Seaman Directing Merchants, Mariners, &c. Adventuring to Sea, How (by God’s Blessing) to Escape Many Dangers Which Commonly Happen in the Ocean. Unto Which (by Way of Appendix) Is Added, A Diary of the Weather for XXI. Years, Very Exactly Observed in London: With Sundry Observations Made Thereon. (London: Printed by Matthew Street, 1697); Nauticum Astrologicum or, the Astrological Seaman; Directing Merchants, Marriners, Captains of Ships, Ensurers, &c. How (by Gods Blessing) They May Escape Divers Dangers Which Commonly Happen in the Ocean· Unto Which Is Added a Diary of the Weather for XXI. Years Together, Exactly Observed in London, with Sundry Observations Thereon (London: Printed for George Sawbridge, 1710).

54 John Gadbury, Nauticum Astrologicum, pp. 95–96, 105, 120–22, 126–27.

55 Ibid., p. 127.

56 For example, in al-Riǧāl, pp. 241–42.

57 Another example of astrology applied to navigation comes exactly from the Ottoman court, on whose archives can be found reports from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by court astrologers regarding propitious dates for launching ships. See A. Tunç Şen, ‘Manuscripts on the Battlefields: Early Modern Ottoman Subjects in the European Theatre of War and Their Textual Relations to the Supernatural in Their Fight for Survival’, Acaib: Occasional Papers on the Ottoman Perceptions of the Supernatural, no. 2 (2021): 77–106.

58 The revolutions of the years of nativities are charts cast for the annual return of the Sun to the same zodiacal degree it occupied at the time of birth. From this chart the conditions of the year for the individual in question are ascertained.

59 Lisboa, Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (ANTT), Tribunal do Santo Ofício, Inquisição de Lisboa, proc. 17749. A reverse calculation of the 1538 revolution based on the chart presented in the Inquisition file makes this forecast more significant. This conjunction took place in the ninth house of the revolution which would signify foreign or overseas places.

60 On the astrological treatises by Diego Pérez de Mesa, see Lanuza Navarro, ‘Astrología, Ciencia y Sociedad En La España de Los Austrias’, pp. 92–98. For a recent study on Pérez de Mesa’s writings and manuscripts see José María Ortiz de Zárate Leira, ‘Manuscrito con obras atribuidas a Diego Pérez de Mesa en la Biblioteca Histórica de la Universidad Complutense’, in Ciencia y técnica entre la paz y la guerra: 1714, 1814, 1914, Vol. 2 (Sociedad Española de Historia de las Ciencias y de las Técnicas, SEHCYT, 2016), pp. 1141–48.

61 Tratado de Astrologia – De diferentes modos de levantar Figura, Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España (BNE), MSS 5995.

62 ‘A sabiendas dexo aqui aquellas disputas sin fundamento de los Arabes de la fabricacion de las naues y de echarlas al agua y esto solo auiso ques lo que Píndaro disse quel oficio del buen marinero es conoçer la tempestad tres dias antes que venga las senales evidentes a la tempestad son – La [conjuncion] de la [Luna] y [Marte], o con estrelas fixas de su naturalesa. Yten el nacimiento o postura del Arturo o boiero del orion de las cabrillas estas estrelas cada año leuantan unas tempestades muy grandes de la misma manera miraras donde esta [Saturno], y si la [conjuncion] o [oposicion] de los luminares mas cercana pronostica tempestades’ – BNE, MSS 5995, fol. 145r.

63 On the long tradition of weather forecast and its connections to astrology, see Anne Lawrence-Mathers, Medieval Meteorology: Forecasting the Weather from Aristotle to the Almanac (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).