ABSTRACT

At the end of the 1920s, Tanganyika Territory experienced several serious rodent outbreaks that threatened cotton and other grain production. At the same time, regular reports of pneumonic and bubonic plague occurred in the northern areas of Tanganyika. These events led the British colonial administration to dispatch several studies into rodent taxonomy and ecology in 1931 to determine the causes of rodent outbreaks and plague disease, and to control future outbreaks. The application of ecological frameworks to the control of rodent outbreaks and plague disease transmission in colonial Tanganyika Territory gradually moved from a view that prioritised 'ecological interrelations' among rodents, fleas and people to one where those interrelations required studies into population dynamics, endemicity and social organisation in order to mitigate pests and pestilence. This shift in Tanganyika anticipated later population ecology approaches on the African continent. Drawing on sources from the Tanzania National Archives, this article offers an important case study of the application of ecological frameworks in a colonial setting that anticipated later global scientific interest in studies of rodent populations and rodent-borne disease ecologies.

1. 1931

By 1931, the number of rodent outbreaks in Tanganyika had become a major concern for the British colonial government charged with the administration of the East African territory after World War I. During the preceding decade, officers stationed in the various provinces occasionally sent in reports of ravenous rodents attacking cotton, millet, and maize fields. In 1930, these reports occurred with such greatened frequency that the Director of Agriculture, E. Harrison, hastily sent a telegram to the Chief Secretary in Dar es Salaam to inform him of the serious ‘multiplication and spread of rats’ being reported in the Mwanza and Tabora Provinces, as well as in the Kilosa and Morogoro areas of the Eastern Province.Footnote1 By the end of January 1931, it became clear to Harrison that he was confronting a potentially devastating crisis. Planters in Morogoro complained that they had lost fifty to seventy per cent of their cotton due to rodents. Harrison pleaded to the Chief Secretary for aid from the Crown Agents. ‘TRANSMIT IMMEDIATELY,’ he commanded in upper case letters, ‘A SUPPLY OF VIRUS OR INOCULANT IN DEALING WITH PLAGUE OF FIELD MICE AND RATS.’Footnote2 Infecting rodents with a lethal pathogen such as ‘Rat Virus,’ ‘Liverpool Virus,’ ‘Danysz Virus,’ or 'Pasteur Virus,’ was controversial given its inconsistent results and danger of sickening humans, betraying Harrison’s desperation for a solution to the crisis.Footnote3

Meanwhile, another crisis was brewing in the north of Tanganyika. Health officers were dispatching reports about locals falling ill with severe pneumonia. They were feverish and coughed up thick blood-stained sputum. Other officers reported seeing gravely ill people with swellings of pus under their necks and arms. Within two months, between December 1930 and January 1931, nine people, including one child, had died of pneumonic and bubonic plague.Footnote4 Toward the end of the nineteenth-century, scientists in Hong Kong had been able to work out that transmission of the ‘plague bacillus’ was the causative agent of this infectious disease. Later studies showed that the disease was transmitted from small mammals to humans when fleas feeding on blood from an infected rodent, for instance, subsequently fed on human blood. As fleas suck on human blood, they regurgitate the bacteria, which in 1944 was named Yersinia pestis, into the human bloodstream. Y. pestis would then spread to the lymph nodes and cause swelling and tissue death.Footnote5 When news of pneumonic and bubonic plague began emerging all across the northern area and lake shores of Tanganyika, this spurred the Department of Medical and Sanitary Services to take quick and drastic action against rodents. Medical officers sent requests to the Secretariat in Dar es Salaam, requesting funds for rodent traps and poisons. By May 1931, plague had spread as far as Nzega and Shinyanga Districts, threateningly near the Central Railway Line, which could then transport stowaway rodents and fleas all the way to the ports at Kigoma and Dar es Salaam that connected Tanganyika to the global economy.

1931 thus marked the year when rodents became a focal point of concern for the colonial administration in Tanganyika. Although written records of rodent outbreaks and plague in Tanganyika and East Africa exist as early as the 1880s, 1931 was a crucial turning point for the scientific treatment of rodents as a matter of colonial state policy.Footnote6 It signals the beginnings of attempts to determine and monitor rodent species and populations, an approach that marked a shift away from rodent control schemes that focused on eradicating rodents to one that leveraged their ecological relationships with other organisms such as crops, fleas, and humans in the environment in order to limit the disease and destruction that rodents wrought on human lives. Such a shift occurring in Tanganyika coincided with and to some degree anticipated the emergence of disease and population ecology as tools for rodent control.

The year 1931 is significant as a confluence of several disruptions to previously stable global and colonial systems of exchange and knowledge. In the wake of the 1929 economic depression, Tanganyika’s dependency on the industrial economies of the U.K. and the U.S. severely decimated its own economy. Export prices for many of Tanganyika’s cash crops such as sisal, coffee, and cotton cratered between 1929 and 1932. The selling price of seed cotton for a Sukuma grower in Bukoba fell seventy per cent from 40 to 12 cents per kilogram, leading many planters to reduce cultivation and move on to longer-term cash crops, such as sisal.Footnote7 Outside of Morogoro town in Kimamba, a major centre for cotton growing, crop production dropped from 124,925 centals in 1929 to 48,030 centals in 1932. The decrease in total areas of cotton growing meant that planters experienced rodent attacks on their crop production with ever more acuity.Footnote8

In terms of the history of biological knowledge, 1931 marked a turning point in the slow but certain shift of biology toward ecological frameworks. Ecological understandings of disease and organisms had begun to take hold among the scientific community in Britain and North America, informing government policy in London and in the colonies. The idea for a Bureau of Animal Population, founded in 1932, emerged in 1931 at the Matamek Conference on Biological Cycles in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canada, driven by investor and scientist concerns over dwindling populations of economically important fish and game.Footnote9 During this time, the relationships between animal population, disease, and ecology became a subject of intense study among pathologists, immunologists, and microbiologists including Charles Elton, Theobald Smith, Frank Macfarlane Burnet, and René Dubos, who frequently incorporated data collected through those very same networks that facilitated (settler) colonialism.Footnote10 Indeed, many of these figures elaborated their ideas of ecology based on data collected from Britain's African colonies, including Tanganyika. Colonial officers such as John Phillips, who was the deputy director of the Department of Tsetse Research at Kondora-Orangi in Tanganyika from 1927-1931, often used the environments of their posting to develop a 'science of ecology' that paid attention to the 'inter-relations' among plants, animals, and people.Footnote11 The ecological concepts developed in Phillips' work were applied not only to the management of disease outbreaks such as African trypanosomiasis, but also to the 'ecological administration of Africa's troubling black population.'Footnote12 In 1931, efforts to reduce rodent and plague outbreaks in Tanganyika prioritised enumerating rodent populations, a marked shift from an ecological approach that focused on the relationships among plants, animals, people, and their environments to one that, following Charles Elton, sought to quantify changes in population numbers. This shift in Tanganyika anticipated population and disease ecology studies in South African public health campaigns beginning in 1938.Footnote13 I therefore contend that Tanganyika was not merely a significant node in the trans-imperial networks of biological knowledge flows but an important location for the coming together of the sciences of ecology and other fields such as epidemiology.Footnote14 Even as colonial officials and indigenous leaders adopted ecological frameworks for plague and pest control from Britain and South Africa, they constantly worked them out in their practical applications according to the needs of local communities within the constraints of a bare bones colonial administration. It is on account of these political, economic, and scientific concatenations, centred in part on rodents in Tanganyika, that 1931 emerges as a crucial year in the history of colonial East Africa.

Historian Karen Sayer has argued that the interwar period saw an increasingly systematic and quantitative approach to the rodent problem in Great Britain.Footnote15 The shift from ‘destruction’ to ‘control’ of rodents not only recognized the indefatigable ability of rodents to maintain their omnipresence in human lives. Rather, it also acknowledged the ecological imperatives that have come to shape wildlife and livestock management. Increasingly, agricultural and medical officers agreed that rodent populations might be controlled by managing their ecological relationships rather than eradicating them. In the colonies, this acquiescence to co-existing with rodents meant that colonial policy increasingly placed responsibility for rodent outbreaks on planters, villagers, and shopkeepers. If, as ecological frameworks increasingly proposed, fluctuations in rodent populations were a natural effect of its ecology, then any outbreak—any failure to track this process—would be the fault of human behaviour. Following this logic, Tanganyika’s colonial administration advocated for solutions to the rodent problem whereby human behaviours, as part of 'inter-relations' among people, fleas, and rodents, are responsible for pest and disease outbreaks. As such, colonial policies focused their condemnation onto ‘slovenly methods of farming’ and ‘dark unsanitary native dwellings.’Footnote16 The rodent, in its ability to transgress and invade human notions of private property and economy, offered a figure through which colonial discussions about indigenous habits and character were articulated. Rodent presence in farms, dwellings, train wagons, and shophouses became a flashpoint for social contestations over the modernizing, capitalist project of colonization.

Scholars, such as Harriet Ritvo and Timothy Mitchell, maintain that animals play significant roles in the histories of many human practices and institutions, including environmental activism, petkeeping, ethics for animal experimentation, wildlife conservation, and livestock breeding.Footnote17 Research into animal histories, however, is rarely straightforward. Documentation and archival sources are organized according to anthropocentric categories, and nonhuman animals themselves rarely leave behind a written historical record. Nonetheless, the historian Etienne Benson insists that animals, including humans, leave behind traces of their movements and behaviours. Benson seizes on the venatic quality of historical research, not dissimilar to the skills required of hunters to track footprints, read signs of excrement, and other ‘infinitesimal traces’ as precursors to the records left behind by historical actors and events.Footnote18 To write a history of rodents in colonial Tanganyika requires a certain degree of tracking and hunting.

Within the context of a colonial archive, the disregard toward recording animal lives also extends to human Tanganyikans, whose lives only appear, if at all, as data points in colonial reports. The exclusion of Tanganyikan experiences and nonhuman animal ones from the historical record belies the silences that subtend any colonial archive.Footnote19 Leaving out both indigenous human and nonhuman lives maintains the power that colonial recorders wielded over their African subjects, placing the African person in the same category and environment as their nonhuman animal counterparts.Footnote20 The conflation between Africans and their natural environment would also inform the ways that ecology came to justify control and change over African ways of lives. Colonial reports in the Tanzania National Archives often cast the figure of the African, along with other immigrant, non-British European planters,Footnote21 as unhygienic farmers responsible for the spate of rodent outbreaks. Nonetheless, there exist crucial moments in the records when colonial officers described how village elders dealt with plague.

In addition to describing colonial rodent control attempts in Tanganyika, I present evidence that local inhabitants were as concerned and involved as colonial officers were when it came to confronting the bubonic plague. Archival sources recorded attempts by the Iraqw Elder, Amnai Inge, to stem a plague epidemic in the Mbulu highlands. The Elder Amnai combined indigenous healing practices and disease control that accommodated other colonial plague control efforts circulating throughout the Empire. The Iraqw Elder’s efforts as well as discussions and disputes among colonial officers about what to do with rodents as pest and pestilence show that medical, agricultural, and indigenous actors in Tanganyika were very much participating in a global effort to control rodent populations that brought with them the threat of economic devastation and disease.

The archival sources in this article come mainly from the colonial records of the Tanzania National Archives in Dar es Salaam. Although folders on livestock animals, rinderpest, and tsetse flies were ample, those on rodents were harder to come by. I did, however, find references to rodents in folders compiled by the Department of Medical and Sanitary Services, the Secretariat, and the Department of Agriculture. As these sources imply, the rodent problem in Tanganyika moved unpredictably between discussions of rodents as agricultural pests and carriers of plague disease. This suggests that colonial administrators were themselves uncertain as to what kind of epistemic thing rodents were, and sought to work this out through scientific studies I describe below. As Ann Stoler would have agreed, colonial archives ‘are records of uncertainty and doubt in how people imagined they could and might make the rubrics of rule correspond to a changing imperial world.’Footnote22 Government departments constantly dawdled and shifted responsibility for the rodent problem to one another, finally deferring to the emergent expertise of biologically-trained officers who, in turn, refused to intervene in the regular, natural, fluctuating periodicity of rodent populations.

In the following, I first introduce rodents as an agricultural problem in the Kilosa, Kimamba, and Morogoro areas of Tanganyika, where continuous rodent attacks on crops forced European settler planters and colonial officers to find solutions to the ‘rodent menace.’ Here, the ecological logic of rodent control emerged over time, gradually reproducing and reinforcing colonial ideas about agricultural hygiene among local and settler agriculturalists. Next, I reconstruct the spate of plague outbreaks in 1931, which caused alarm in the colonial administration and threatened to further devastate an economy already reeling from global depression. Rodents were disease carriers, and plague prevention was predicated on changing local behaviours around practices of farming, house building, and sanitation through law and propaganda. In finding solutions to rodents as agricultural pests and disease carriers, colonial officers gradually began looking to ecological research into the fluctuations of rodent populations. I show that a focus on the natural ebb and flow of rodent populations and their interrelations with human activity allowed colonial officers to locate the responsibility for plague prevention and pest control in the realm of social policy. Rather than devise strategies and technologies to kill rodents, colonial policy placed pressure on farmers, shopkeepers, and villagers to maintain sanitation by ‘building out the rat.’ 1931 therefore serves as a key juncture for considering how the rodent problem, once it was recognized as an economic, agricultural, and medical problem for colonial Tanganyika, would be transformed by subsequent ecological research into a matter of social practice and policy.

2. A rodent menace

At the end of January 1931, reports of rodent attacks on cotton crops in Kimamba and Kilosa, outside of Morogoro town, had become incessant. The Director of Agriculture in Tanganyika, E. Harrison, wrote a sternly worded letter to urge the colonial administration to immediately supply a lethal virus that could be used by officers to infect rodents. The infected rodents would develop a kind of typhoid fever and die in large numbers. Before Harrison was appointed to his post in 1930, the Acting Director of Agriculture, H. Wolfe had already sent requests to the Medical Department to investigate the ‘new rat virus developed by the Pasteur Institute, Paris’ as a rapid means of destroying these rodents.Footnote23 To both Harrison and Wolfe’s dismay, the Director of Medical and Sanitary Services (DMSS) refused to help, because ‘the spread of rats was not accompanied by disease,’ although this reasoning would later be dropped when the two departments jointly requested funds for rodent research.Footnote24 The Chief Secretary finally intervened, noting that supplying any kind of rat poison should not be the responsibility of either the agricultural or medical department, but that if ‘a poisoning campaign is to be undertaken’ then it should be carried out through the Native Administration.Footnote25 The matter would remain unresolved, leading Harrison to cable an urgent direct request to London, pleading for rat virus.

At Whitehall in London, the Secretary of State responded curtly to Harrison’s pleas for ‘rat virus.’ ‘I am advised that it is not possible to recommend effective virus which would be harmless to human beings,’ he wrote, and sent the message to the Governor of Tanganyika, Sir Donald Cameron.Footnote26 The ‘Rat virus’ was possibly a culture of Salmonella typhimurium, which when introduced to a rodent population, would spread widely and kill the rodents rapidly with typhoid fever. The ‘Rat virus’ was one of several experimental methods of killing rats that companies were releasing to the market during the interwar years when rodent control became a European and colonial priority. As with most experimental methods, the research was inconclusive as to whether the Rat virus was harmless to human beings or to domestic animals. A circular distributed by the Ministry of Health in the UK discourages the use of the virus near food because the virus was identical ‘with that found in many outbreaks of food poisoning.’Footnote27 The Director of Medical and Sanitary Services, A. H. Owen, agreed with the Ministry’s circular. He upheld a ban on importing the virus to Tanganyika and expressed anxiety about Harrison’s eagerness to obtain such an experimental solution. ‘Until scientific evidence is produced that satisfactory practical results may be reasonably expected from the use of [the virus] I regret that I am unable to recommend the waiving of the restrictions against their import,’ Owen wrote.Footnote28

Given the risks and the government’s reluctance to import the experimental virus, Harrison had to resort to other means of resolving the rodent problem. But a lack of funding and staff hampered his own department’s work. The department did not have the funds to purchase sufficient quantities of barium carbonate rat poison. Harrison instead had to tell planters to go to Dar es Salaam to buy their own, blaming the DMSS for the lack of aid.Footnote29 The rodent attacks continued relentlessly. Desperate representatives of European planters’ associations insisted on a meeting with the Department of Agriculture. At the meeting in April 1931, planters told Harrison that they had seen the severity of rodent attacks on their matama (millet), maize, and cotton crops increase over the years.Footnote30 They expressed worry about what might happen if the government did not take any action. In September 1931, their fears were realized. The rodent problem slashed Kimamba’s annual cotton production from 4,000–5,000 bales to between 500 and 1,000. This 80 per cent loss was so alarming that the Chamber of Commerce threw in their support with the planters and called the government to act immediately. ‘Sympathy [from the government] alone will not destroy this pest,’ they complained and added that ‘more practical steps were needed and also monetary assistance.’Footnote31 These European planters believed that their losses amounted to something between £40,000 and £50,000.Footnote32 Soon, the Tanganyika Ginneries’ Association also called for action.Footnote33 The President of the Tanganyika Planters’ Association warned the government at a special general meeting convened to address the situation that if nothing is to be done about the rodent ‘menace,’ it was ‘the fear of planters in the Eastern Province that the most important cotton producing area—Kimamba—might experience … disaster.’Footnote34

Amid the tumult and uproar at the Department of Agriculture, Harrison, who could not supply poisons or staff for killing rats, looked elsewhere for a solution. He tried again to assign responsibility for the rodent menace to DMSS, but this time framed the problem as a scientific, rather than a practical, one. ‘Would it be possible,’ he wrote, ‘for the Department of Medical and Sanitary Services to have this important rodent studied from the point of view of the Zoologist?’Footnote35 A. H. Owen, Director of DMSS, agreed with Harrison’s suggestion. ‘Any serious attempt to deal with the rodent population of the whole Territory should, I consider, certainly be preceded by a scientific investigation into their habits, breeding grounds, etc. and this would have to be carried out by a trained Zoologist,’ he concurred. Harrison’s idea came at an opportune moment when Owen, as the next section will show, was himself dealing with multiple outbreaks of plague transmitted by rodents in the northern areas of Tanganyika. A scientific investigation at the Territorial scale would lay the foundations for a more coordinated and effective response. ‘Our present methods of poisoning, trapping and rat drives etc. merely deal with the local problem in an area which may be threatened by plague or where damage is being done to agricultural products,’ Owen added.Footnote36 In other words, a scientific study could bring together agricultural and medical rodent control fulfilling hopes for a more unified colonial administration. Harrison was enthusiastic and added in another letter that such a study would yield benefits beyond Tanganyika, and indeed, for all of Britain’s East African Territories, as well as the greater Empire, including the Federated Malay States, where rice crops were frequently attacked by rats.Footnote37

Harrison and Owen soon realized that they did not know anyone in the Tanganyika Civil Service who was trained as a zoologist, let alone anyone with scientific training in the ecology of rodents. The Chamber of Commerce as well as the Planters’ and Ginneries Associations did not have anyone to recommend. In the following weeks, Owen sent a sanitary superintendent, C. W. Manton, to Pretoria, South Africa, to learn about rodent destruction from experts there.Footnote38 South Africa’s network of research stations, museums, and agricultural experiments have made it a centre of British colonial science about disease, pest control, and wildlife protection on the continent. Harrison, meanwhile, reached out to the East African Agricultural Research Station in Amani in the north of Tanganyika for further advice. Its director, W. M. Nowell, agreed that a systematic study of rodents would be necessary and promised that he would be willing to oversee the research.Footnote39 External funding for such an undertaking would be needed, however, and this would require that the government first prepare a detailed preliminary report on the present rodent situation in Tanganyika.Footnote40 Scrambling together what resources he had, Harrison assigned W. Victor Harris, the Assistant Entomologist at his department’s offices in Morogoro to investigate the rodent problem in Tanganyika.

Trained in entomology, W. Victor Harris was more familiar with the ways of the borers, weevils, termites, and other insect pests. But he would apply his entomological training to the collection and dissection of rodents, beginning a six-month study in December 1931 at the request of the colonial government. Systematising rodent trapping, collection, identification, and population numbers, Harris’s study marked the beginning of a long history of scientific rodent research in Morogoro. His regular trap-and-release experiments to estimate rodent populations in agricultural areas would set the scene for later, post-independence research work that would develop, in the twenty-first century, into the Sokoine University of Agriculture Pest Management Centre located in Morogoro town, a global centre for rodent research.

3. To wage a great war against these enemies

The Great Lakes region of East Africa has long been a place where plague is endemic. Apolo Kaggwa’s account of Buganda kingship, spanning from the 1300s through 1884, mentions a huge outbreak of rats in the Buganda capital on the shores of Lake Victoria (or Nnalubaale) as early as the eighteenth century.Footnote41 Kaggwa later refers to a plague that killed many people, including ‘about three hundred royal wives’ in 1879.Footnote42 By then, there were several other contemporaneous accounts of plague disease on the western shores of Lake Victoria. British missionaries like Robert Ashe encountered plague in the central provinces of Uganda as early as 1887, documenting reports of a disease known as ‘kaumpuli’ that decimated huge swathes of the population in the Buganda kingdom long before the arrival of British colonists.Footnote43 Just south of the Buganda kingdom, the earliest reports of plague in Tanganyika were recorded in Kiziba in Bukoba (1897) and further south in Iringa (1886); there were further reports of outbreaks in Shirati in Mwanza (1901) and Rombo in East Kilimanjaro (1912).Footnote44 A plague outbreak in Nairobi, Kenya in the first decade of the twentieth century is also well-documented.Footnote45 Collectively, these incidences of plague lend support to the argument that the branching in the phylogenetic tree of Yersinia pestis in East Africa may have originated in the European Black Death of the fourteenth century and was endemic to the Great Lakes region before the third plague pandemic that began in 1894. Memory of this epidemic history is inscribed in the Kiswahili word for plague, ‘tauni,’ which comes from ‘ṭāʿūn,’ the Arabic word for the disease, suggesting earlier routes of transmission established by African and Arab participation in the trade of ivory and slaves that stretched into the continental interior. The fact that many of these outbreaks predated the arrival of railway lines suggests that they were independent of plague strains from pandemics in Hong Kong and Bombay at the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote46

Many of these same places in Tanganyika would experience plague outbreaks again in the 1920s and 1930s, causing a significant number of deaths among the local population. In Uganda alone, 5,199 people died from plague in 1929.Footnote47 Fortunately, the number of fatalities from plague in Tanganyika would never come close to this number. The mortality data, however, is unreliable. Reporting officers often could not confirm if these deaths were due to plague or a disease with similar symptoms such as anthrax or malaria. Clinical confirmation of the bacillus through a test known as bipolar staining sometimes indicated that there was no plague, despite the observed patterns of infections and rodent deaths. There is therefore no clear data for the total number of people who died from plague in Tanganyika under the British mandate, but archival sources consistently documented plague outbreaks through to the 1950s. During the postcolonial period, plague would flare up again in the 1970s and 1980s in the same places as those at the turn of the twentieth century for reasons that are still unknown.Footnote48 Based on my own tally from archival records, 1931 saw approximately 90 officially recorded deaths. Despite the relatively low mortality rate of plague in Tanganyika, the severe death toll in Uganda caused alarm among colonial officers in Tanganyika when they started receiving reports of possible disease outbreaks in Tanganyika’s Northern Province.Footnote49

There were three recorded plague outbreaks in Mbulu district, about 100 miles southwest of Arusha, in 1930. During each outbreak, a senior medical officer or surgeon would be dispatched by the provincial administration to evaluate the situation. He would make hasty arrangements to travel, bringing along supplies to collect samples so that he could clinically determine the disease.Footnote50 Based on the diagnosis, he would then coordinate a response with the Native Administration while keeping the government, in this case, the Department of Medical and Sanitary Services (DMSS), informed. I draw on these reports and letters to reconstruct how the colonial government in Tanganyika managed plague outbreaks in the late 1920s leading up to 1931, when the scale of outbreaks threatened to spill out from their rural locations and onto the port city of Dar es Salaam.

In December 1930, when the first of a series of serious plague outbreaks erupted in Mbulu, Amnai Inge, an Iraqw Court Elder who worked for the Native Authority and was highly respected in his village, lost a child to bubonic plague. After the death of his child, Amnai set fire to his entire house, isolated himself, and sent in a report to Moshi, which was received by R. Nixon, the Senior Health Officer. Nixon was immediately sent to Mbulu to investigate the situation. Upon his arrival, Nixon learned that several more deaths had occurred, totalling nine at the end of January 1931. He also learned that under Amnai’s direction, the entire village of 420 people would voluntarily go into quarantine for 10 days after the last notified case of plague. After the ten-day quarantine, they would burn their entire village and then move to and settle in a new area. Amnai requested that the Native Authority begin building 80 houses in the new area, located across a stream, which would act as a natural barrier against rats. At the stream crossing, the Iraqw villagers would remove all their clothing, which would then be sprayed with paraffin to kill any fleas. The DMSS refused to provide any funds for this endeavour, saying that it was not the responsibility of the medical department to buy soap and paraffin oil. The Native Authority had to step in and pay for disinfectant using tax money collected from the villagers. The miserliness of the colonial government so clearly embarrassed the acting district officer, L. S. Greening, that he wrote to the provincial commissioner in Arusha to see if he could authorize any funds to buy disinfectant and ‘Amerikani’ cloth that villagers would use once they have stripped off their clothing at the stream.Footnote51

At the time, the colonial government of Tanganyika did not yet have a coordinated strategy for dealing with plague epidemics. This timeline suggests that Amnai’s quarantine and relocation strategy was based on knowledge and experience circulating locally.Footnote52 The history of plague’s endemicity in this part of the world and the fact that I did not come across another quarantine and relocation strategy in the archive strengthens this claim. As the historian Mari Webel argues, the practice of burning down the home of a person who has died of plague and subsequent quarantine measures for those at risk of infection in Kiziba accommodated both indigenous and colonial responses to fatal diseases.Footnote53 As an officer in the Native Authority and a village elder, Amnai would have been literate, well-respected, and well-connected. He would have been aware of both colonial and indigenous practices for plague control and was certainly engaged in thinking deeply about the social and economic changes that were unfolding before him. In addition to adapting the indigenous practice of burning to colonial policy, Amnai adopted building policies around rat-proofing. He was a proponent of encouraging his fellow Iraqw in Mbulu to build their houses out of brick rather than mud, wattle, and grass.Footnote54 Amnai’s leadership represents a tiny but crucial part of a larger array of experiences that, unlike Amnai’s, were not recorded in the archive. His strategy to quarantine and relocate is evidence that Tanganyikans did not just possess knowledge about plague but were active participants in adopting and adapting current plague control efforts to their own circumstances. Despite this, indigenous inhabitants are mostly portrayed as victims of the disease, whose habits are blamed for spreading it (as I shall soon show).

Amnai’s quarantine and relocation measures were insufficient for Nixon. For Nixon, these measures resolved the immediate threat of the disease but they were deemed inadequate in preventing future outbreaks of plague. Colonial officers at DMSS, based on their consultations with London and South Africa, wanted to ensure that ‘native dwellings’ be as inhospitable and inaccessible as possible to rats, which were seen as the primary vector of the disease because they carried infected fleas into a dwelling. These fleas would bite and infect the dwelling’s human inhabitants and cause plague. To this end, Nixon advised district officers to ‘encourage the natives to keep cats’ since ‘Wambulu dogs appear to have no value as ratters.’ Additionally, the resettlement of the Iraqw, or Wambulu, in a new area means that the government can ‘get the Wambulu out of their tembe huts into dwellings from which it is possible to exclude the rat.’Footnote55 Tembe hut is the term colonial officials used to describe rectangular houses built low into the ground, made with wooden frames, thatched roof, and mud walls typical of the Iraqw homestead in the twentieth century. To colonial officials, these structures permitted a porosity between the house and its environment that encouraged rodents from the wilderness and the farm to enter into the house, carrying along fleas infected with Y. pestis. In other words, colonial measures against plague were as much about changing Iraqw ways of life as it were about stopping the transmission of disease. The plague outbreak in Amnai Inge’s village became an experimental system for changing how the Iraqw lived, further incorporating them into the modernist and capitalist project of colonialism.

In discussions among officers at the district office and DMSS, the rat very quickly became more than just a disease carrier. The rat’s threatening presence, crossing from wilder places into the domestic space, came to index indigenous backwardness and foolishness. As the resettlement approached, colonial officers schemed and discussed different ways to get the Iraqw to adopt rat-proofing strategies in their new village. A provincial commissioner sent in a note, describing Iraqw strategies for plague control as ‘very wasteful’ because they ‘invariably abandon a dwelling in which a death has occurred, using the poles for firewood.’ Such ‘superstition,’ he wrote, would prevent them from building better houses given their ‘habit of evacuating and destroying a house when one of the inmates dies.’Footnote56 L. S. Greening, the acting district officer, was even more condescending. Encouraging the Wambulu to keep cats was not ‘practicable,’ he opined, because the ‘natives … would never think of feeding a cat.’ He then revealed that ‘I personally destroy any surplus kittens rather than give them to a native.’ Greening reported that the Wambulu’s ‘outlook’ was that ‘fed cats will not hunt’ and therefore they refused to feed any cats, resulting in ‘poor half-starved creatures [that] are too weak to hunt and [that] live by scavenging.’Footnote57 For these officials, modernity, or its lack, of the Iraqw was measured by how the Iraqw configured their multispecies relations among rodents, cats, and dogs.Footnote58

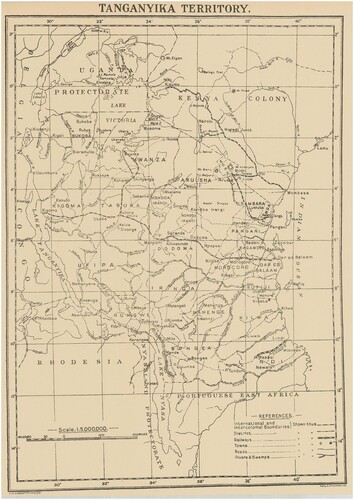

Although Amnai Inge’s village did not experience any more deaths in 1931, the efforts may have come too little too late to stem a larger epidemic. By May 1931, there were reported outbreaks of plague in Nassa town (3 deaths), Tabora town (several deaths), Nzega district (40 deaths), Shinyanga district (15 deaths), and Maswa district (15 deaths). Notices were sent to the League of Nations Health Organization’s Eastern Bureau in Singapore as part of reporting requirements under the International Sanitary Convention of 1926, which instituted an international surveillance system of epidemic diseases.Footnote59 As the death tally from plague in Tanganyika continued to rise in the northern, central, and lake regions of the country, the colonial government started to worry that the locations of these outbreaks were too close to the Tabora-Mwanza line of the Tanganyika Railway (see ).Footnote60 What happens when plague-infected rodents and fleas hitched a ride on the train and ended up as far east in Dar es Salaam? What if rodents were accidentally smuggled onto a cargo ship bound for Marseilles or Mumbai?

Figure 1. Map of Tanganyika Territory (1931) showing railway lines. London, UK: His Majesty’s Stationery Office. Princeton University Library.

By June 1931, 205 cases of plague had been reported in the Tabora Province.Footnote61 R. R. Scott, who was Director of DMSS in 1931, immediately consulted the General Manager of Tanganyika Railways, going over several possibilities for implementing ‘disinfestation,’ which included inspecting train loads of agricultural produce, fumigating train trucks, and rat-proofing the warehouses near the railways.Footnote62 At the same time, Scott instituted regular ‘deratisation’ efforts on all vessels on Lake Tanganyika, where cargo from the Belgian Congo usually crossed to make their way to the port of Dar es Salaam by rail.Footnote63 In June, the DMSS drafted, published, and distributed a pamphlet on plague in Tanganyika to aid in these efforts. The pamphlet would streamline the various anti-plague measures that the colonial government had been receiving from London, South Africa, and Uganda, and would serve as a resource for medical officers at the district and provincial levels as well as the Native Authorities tasked with enforcing anti-rat measures. The DMSS sent out the pamphlet with a circular that came in English and an abridged version in Kiswahili, along with broadsheets that could be posted in village squares, schools, and administrative offices as part of a nascent anti-plague campaign.Footnote64

The pamphlet provided a brief history of plague in East Africa, its modes of transmission, the effects of the disease (including death), and measures for preventing it. The pamphlet identified the rodent, particularly the common black rat, as the ‘usual immediate source of infection’ because they live ‘in close association with man.’Footnote65 The best way to prevent plague, according to the pamphlet, is to ‘break the chain connecting rat to man.’ It warned against ‘extensive rat-killing campaigns in the absence of actual infection’ because they do not actually reduce rat populations due to their rapid rate of breeding. However, during an outbreak, ‘such campaigns are valuable’ because they reduce the probability of infected rats carrying fleas to come into contact with people. The most ‘practicable’ anti-plague measure is to ‘build the rat out.’ This means improving existing buildings or constructing new ones that adhere to new building rules introduced by the government in 1930.Footnote66 The enforcement of these building regulations, however, was confined to urban areas. The issue of ‘native dwellings’ in rural areas, which represented much of the building structures in Tanganyika, required a different response. In cases where building out the rat were impossible, such as in tembe houses, measures must be taken to prevent rats from making their homes and obtaining food in these houses.Footnote67

Measures regarding ‘native dwellings’ were given little priority in the eight-page English pamphlet but they took up almost half of the abridged version of the pamphlet that was printed in Kiswahili. The Kiswahili version is titled as a government order (‘amri serikali’). The order invokes the language of military service to recruit people to fight a ‘great war’ against rodents, which I have translated below:

Basi yapasa kila mtu kupigania vita vikubwa na hao adui waambukizao ugonjwa; na vita vipigwe hivyo:- 1) Kuweka akiba ya vyakula katik vyombo visivyoweza kuingiliwa na panya, kama mitungi au madebe. 2) Kufunika mitungi na mapipa ya maji manyumbani, panya wasipate maji ya kunywa. 3) Kutoa kila kitu cha nyumbani, kisha mwaga maji kidogo chini na kufagia, na kuchoma moto takataka zote zilifagiliwa. 4) Kupeleka pamba na sufi na karanga na mavuno ya namna hizi upesi madukani, yasiwekwe siku nyingi manyumbani.

Everyone must thus wage a great war against these enemies who spread the disease; and the war would be fought in this way:- 1) Keep stores of food in rat-proof vessels such as clay pots or tin cans; 2) Cover water jugs and barrels to prevent rats from getting water to drink; 3) Put everything out of the house, splash some water on the floor and sweep, then burn the sweepings; 4) Make sure that cotton, kapok, groundnuts, and the like are sent to the shop quickly; do not keep them for many days at home.

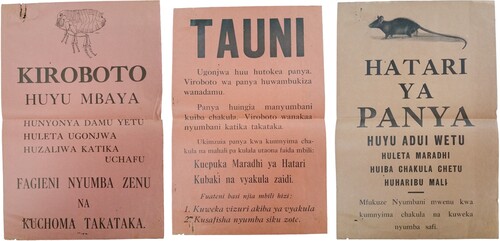

Accompanying the government order are several printed broadsheets in Kiswahili with instructions for district officers and Native Authorities to post them in public places, such as at markets, meeting places, village leaders’ homes, and administrative buildings. As with the government order, the purpose of these broadsheets was not to educate people about plague so that they would be able to identify symptoms of the disease and seek immediate treatment. Rather, the colonial government was concerned with the economic impacts of the disease, affecting crop production and decimating the labour force. As such, these broadsheets (see ) explained that plague was a disease spread by rodents and fleas to humans and included measures that people can take to reduce human-rodent and human-flea interactions in their homes .

Figure 2. Broadsheets (1931) in Kiswahili about fleas (‘kiroboto’), plague disease (‘tauni’), and rodents (‘panya’). TNA 11901/v1.

Additionally, the language used in these broadsheets suggests that the success of these anti-plague measures depended on crafting villainous profiles of the nonhuman animals involved. The language differentiates between rodents, fleas, and humans by performing a shared humanity between colonial officials and local inhabitants through the use of the pronoun ‘our.’ One broadsheet declares ‘The Danger of Rodents!’ with an image of a Rattus rattus (black rat). It goes on to describe the rat as ‘our enemy, who brings disease, steals our food and destroys property.’ The other broadsheet declares that the flea is a ‘villain, who sucks our blood, brings disease, and breeds in dirt.’ That shared humanity created between colonial and colonised person, however, dissipates toward the end of the broadsheets, where instructions take on the pronoun ‘your.’ ‘Banish [rodents] from your home by withholding food and keeping a clean house,’ directed one broadsheet while the other tells its readers to ‘sweep your houses and burn the sweepings.’ These instructions differentiated colonised Tanganyikans from colonial officers, admonishing local habits of hygiene and upkeep and importantly, placing the responsibility for preventing plague on the inhabitants. Visual representations such as these broadsheets explain the transmission pathways of zoonotic diseases from animals to humans to emphasize the final link that connect humans to the animal vectors. As Christos Lynteris has argued about zoonotic diagrams, these broadsheets emphasize human responsibility (and fault) for spillover events, when a disease can infect a secondary host species.Footnote69

By the end of 1931, the number of plague outbreaks had subsided. Colonial officials were relieved and took the opportunity to conduct further research on the rodents themselves. Up until 1931, medical and district officers assumed that the main vector of plague was the Rattus rattus, or the common black rat, also known as the house rat (panya nyumba in Kiswahili). Because these rats mostly lived close to human habitation, fleas infected with Y. pestis must have entered the homestead and settled on the house rat through some other vector. No one was certain what small mammal was the responsible connector, but many officials recorded suspicions about field rodents. As was the dominant view in South Africa, field rodents were thought to carry infected fleas from sylvatic rodents to house rodents.Footnote70

When the Director of Agriculture in Morogoro suggested a zoological study of rodents as disease carriers and agricultural pests to resolve these questions, the Director of Medical and Sanitary Services agreed. More information about the species, behaviours, and ecology of rodents in Tanganyika causing crop damage and plague disease would be helpful to better shape government policy and distribute funds for poisons, traps, and other methods for rodent control. After the multiple outbreaks of plague and rodents of 1931, the colonial government made some funds available to conduct several preliminary studies of rodent species and population in the Tanganyika Territory. These studies, even as early as 1931, had begun incorporating ecological frameworks to explain rodent outbreaks and, therefore, design policy for controlling rodent populations.

4. A futile and soothing approach

When several tins from Tanganyika containing the preserved bodies of various rodents, which were stuffed with cotton, wrapped in gauze, numbered, and soaked in a Formal saline solution, arrived in the office of Austin Roberts, a senior assistant in the higher vertebrates section of the Transvaal Museum in Pretoria, South Africa, Roberts was not at all pleased. ‘The specimens were not prepared in the usual way,’ he complained, ‘very incomplete and therefore not readily identifiable.’Footnote71 Roberts valued precision and it was his commitment to the orderliness of nature that made him a well-known ornithologist and mammologist. But it was his experience with plague-carrying rodents that was being sought after by the colonial government in Tanganyika. Roberts was well-recognized by the South African government for his efforts to determine which species of rodents harboured plague during outbreaks in the 1920s.Footnote72

Whereas anti-plague approaches in South Africa conceptualized the disease as a result of a disturbance in the ‘balance of nature’ caused by urbanization and industrialization, colonial officers in Tanganyika took on a more quantitative type of ecological thinking.Footnote73 The various rodent studies launched at the end of 1931 envisioned that rodent taxonomic and population studies would provide solutions to the growing rodent menace that threatened to damage crops and spread disease. The Director of Agriculture assigned W. Victor Harris, an assistant entomologist at the department’s office in Morogoro, to conduct a six-month study to gather data about rodent numbers, behaviours, and parasites. These studies had two main goals. The first was to establish which species of rodents were harbouring plague or causing damage, since taxonomy would help clarify the organization of relationships between behaviour, environment, and organism. In the immediate wake of the multiple outbreaks of plague and rodents, rodent bodies and body parts circulated up and down the eastern seaboard of the African continent. Specimens were being transported north to the British Museum or south to the Transvaal Museum for identification as part of efforts to understand the behaviour and ecology of rodents. The second goal is to offer a Territory-wide strategy for eradicating rodents. This strategy would rely on disrupting the breeding and migratory patterns of rodents. A ‘different system is required to deal with [rodent] migrations and their prevention,’ wrote the Director of Agriculture in an update to the press, and added, ‘Such a system can only be arrived at by a study of the problems, and finding where the mice multiply.’Footnote74

Harris completed the six-month study in May 1932. In his report, he was able to identify 17 species of rodents. He trapped and released hundreds of mice and rats every four weeks, whose numbers provided the first data points for establishing the periodicity of rodent populations in the plantations surrounding the Morogoro area. Harris selected 42 rodents for examination. He combed their furs for ectoparasites, collecting any fleas and fleas that fell out. The rodents were then dissected so that internal parasites could be collected from their organs for identification. In the report, Harris noted that there were several species that formed what was known as ‘grey field mouse,’ including Praomys tullbergi and the multi-mammate Mastomys sp. mouse. Harris also identified the common black rat, or Rattus rattus, as responsible for attacking crops. Occasionally, he caught a ‘Giant Rat,’ or Cricetomys gambianus, which Harris noted is a species known to attack maize fields in the Uluguru mountains. He concluded the report with a guide on preparing poison baits and suggested that the four-weekly catch and dissection be continued to develop a good understanding of the ‘inter-relations of the species grouped together.’Footnote75

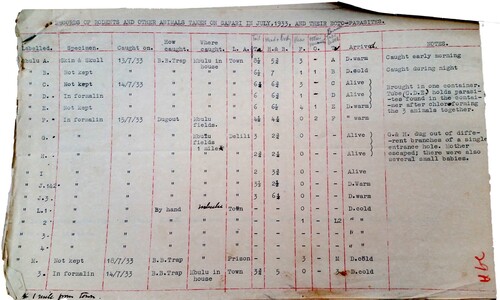

Studies such as Harris’ were conducted regularly in 1932 and 1933. In the northern areas of Tanganyika, medical officers arranged tours to trap, collect, and identify rodents and their parasites, with the goal of elaborating an ecology of plague. The studies that reported to the Department of Medical and Sanitary Services were more concerned about determining which rodent species were ‘plague reservoirs.’ One such tour was led by Dr. A. R. Lester, a senior health officer based in Shanwa district. His tour covered a wide area, from Mwanza on the shores of Lake Victoria to Tabora, near the central region of Tanganyika (see ). Lester and his team trapped over 1500 rodents and dissected over 700, sometimes preserving whole specimens and other times keeping just their skins. They tested the 700 spleen smears for Y. pestis and found that they were all negative for plague.Footnote76 Select specimens from this tour and another one in Dar es Salaam were then forwarded to Pretoria, where Austin Roberts would be charged with identifying their species.

Despite the shoddy preservation of the rodent specimens sent to South Africa, Roberts identified Rattus rattus, Tatera swaythlingi (a gerbil known for spreading bubonic plague in South Africa), Mastomys coucha microdon (a multimammate mouse ‘with no striking characteristics’), Lemniscomys barbarus albolineatus (or striped mouse, ‘frequenting cultivated ground, not usually entering houses’), Arvicanthis abyssinicus muansae (or Abyssinian Rat, whose ‘genus does not extend into S. Africa’), and Elephantulus ocularis (elephant shrews, ‘not rodents nor potential plague carriers’).Footnote77 The conclusion was that only two or three species of rodents caught in Tanganyika were known to be carriers of plague, and that they were sylvatic, that is they usually lived in the bush and are not likely to enter homes and transmit plague to humans. Additionally, there had been no reported mass rodent deaths that year. All of this made it difficult to say for certain whether plague was dormant or even endemic to the region. Additionally, all of the 700 samples of spleen smears from domestic, semi domestic and wild rodents were negative for plague. The study essentially failed to produce any useful information that would help the colonial authorities prevent future outbreaks of plague .Footnote78

Figure 3. ‘Records of Rodents and Other Animals Taken on Safari in July, 1933, and their Ecto-parasites.’ Note that specimens were collected in the Mbulu area. TNA 450/106/9/29A.

Disappointing results also came in from the Morogoro area. As Harris’ rodent study continued into 1933, it failed to show that there were any outbreaks in rodents nor plague. In June 1933, planters including a manager at Rudewa Estates Ltd. (formerly the Tanganyika Cotton Company) said that they had not seen any rodents in months. Harris also reported that when he immediately examined the bodies of rodents after they were killed, he had not found any fleas.Footnote79 Yet, when outbreaks occurred, they seemed to happen swiftly without warning, causing great damage. By 1937, these studies had yet to bear fruit in the form of a concerted strategy for dealing with pest or pestilence in Tanganyika. As in 1931, a wave of plague outbreaks rippled across the same areas in the first half of 1937. There were two cases of plague reported in Mbulu, sixty cases and sixteen deaths in Singida, and eight deaths in Mwanza.Footnote80 The disease had struck within the urban areas of Mwanza town this time. As a result, town residents, most of whom were Indian traders, evacuated and fled to the coastal areas.Footnote81

Despite their inefficacy in preventing future rodent and plague outbreaks, these studies continued through to the post-independence era. Even in the absence of any clear results from these studies, colonial administrators in Tanganyika internalised the ecological assumption inherent in these studies. This assumption held that rodent and disease outbreaks would occur at regular intervals according to the relationships between a population of animals and their environment. ‘It may, therefore, be expected that further outbreaks will occur from time to time,’ read the official circular from the colonial government in reference to both rodent populations and the incidence of plague.Footnote82 The best prevention methods seemed to be disrupting those ecological relationships. Since so little was known about the rodents themselves, despite these ongoing studies, the colonial government tried to change the environment by enforcing strict separations between humans and rodents, usually placing the burden and responsibility for carrying this out on local Tanganyikans and non-British immigrant planters. Although district offices often kept a supply of traps and poison, along with manuals for baiting, these were often insufficient to contain the kinds of sudden outbreaks that caused severe damage to crops or transmit disease. In other words, both the Departments of Agriculture and Medical and Sanitation Services placed the responsibility for managing rodent outbreaks on those who bore the greatest brunt of rodent attacks.

As the colonial government increasingly took the position that rodent outbreaks and plague were part of a natural order, their response began to focus on ensuring that urban areas, ports, railways, and homesteads were inhospitable environments to the rodent, resulting in significant changes to existing or local ways of life. In the case of plague, we have seen earlier how the tembe house of many Tanganyikans were derided as being ‘insanitary.’Footnote83 The colonial government also adopted new regulations that mandated that buildings in townships be sufficiently rat-proof. These rules prevented the storage of grains in places where people slept and set out conditions for the hygienic maintenance of bazaar areas.Footnote84

In the cotton planting areas of Kimamba and Kilosa, the ‘dirty’ harvesting practices of Tanganyikans who worked on the plantations were eventually blamed for rodent outbreaks. ‘The rat plague in the Kimamba district is due almost entirely to the fact that Kimamba farmers are ‘dirty’ farmers, that is to say, they leave food in the fields and fail to harvest their crops, both of which attract rats in large numbers,’ wrote D. J. Jardine, the Chief Secretary to the Tanganyika government.Footnote85 Leaving cotton unharvested, however, was a crucial strategy that Tanganyikan workers and immigrant planters used to assert some level of control over the commodity’s depressed market price, which was slowly recovering after the Great Depression.Footnote86 Indeed, such ‘slovenly methods of farming’ gradually justified the government’s lack of interest in addressing the rodent problem. ‘I am decidedly of the opinion that in such circumstances it is the duty of the agriculturalist to help himself, so far as it lies within his power to do so by maintaining a reasonable standard of farming practice,’ W. M. Nowell, the Director of Amani wrote in a letter to the government to voice his opposition to using any government funds to hire a rodent ‘specialist.’Footnote87 These notes and letters would inform later government policy to encourage and sometimes enforce ‘clean’ farming methods, including the storage of harvested crops in rat-proof containers as part of a larger ‘building out the rat’ strategy.Footnote88

Various ecological views of nature began to revolutionize research methodology and biological theory in Britain beginning in the 1920s. This paradigmatic shift was further helped with the publication of Animal Ecology (1927) by Charles Elton, who would also later establish the Bureau of Animal Population at Oxford in 1932. In the introduction to the book, Julian Huxley enthusiastically endorsed the work of his former student, calling ‘the subject of animal numbers’ a field that is of ‘fundamental importance’ to the field of biology.Footnote89 By changing farming practices to reduce the probability of future rodent outbreaks, the colonial government in Tanganyika hewed closely to the emergent paradigm of population dynamics that was taking hold inthe imperial science of ecology. This view is best summarized in Huxley’s introduction to Animal Ecology:

… it may often be found that an insect pest is damaging a crop; yet that the only satisfactory way of growing a better crop is not to attempt the direct eradication of the insect, but to adopt improved methods of agriculture, or to breed resistant strains of the crop plant.Footnote90

Readers of Mr. Elton’s book will discover that these violent outbreaks are but special cases of a regular phenomenon of periodicity in numbers, which is perfectly normal for many of the smaller mammals. The animals, favoured by climatic conditions, embark on reproduction above the mean, outrun the constable of their enemies, become extremely abundant, are attacked by an epidemic, and suddenly become reduced again to numbers far below the mean … The organisers of the anti-rodent campaign claim the disappearance of the pest as a victory for their methods. In reality, however, it appears that this disappearance is always due to natural causes, namely, the outbreak of some epidemic; and that the killing off of the animals by man has either had no effect upon the natural course of events, or has delayed the crisis with the inevitable effect of maintaining the plague for a longer period than would otherwise have been the case!Footnote92

This view also influenced the emergent field of disease ecology, in which microbiologists and pathologists begin to apply population ecology to understanding disease transmission. From the Central Asian plains to the Central Valley of California, ecologically-minded biologists began to pay attention to climatic oscillations that corresponded with population fluctuations of small mammals suspected to be reservoirs of plague and other infectious diseases. ‘The most important conclusion which can be drawn,’ Charles Elton wrote in a summary of data collected about the occurrence of plague in Central Asian marmots and other small mammals, ‘is that epidemics have a definite periodicity in many cases, i.e. instead of being irregular and unpredictable phenomena, they obey regular laws.’Footnote93 Elton argued that epidemics, which resulted in mass deaths of a population of animals, were the mechanism by which most rodents regulate their numbers. Given that both disease and rodent outbreaks are part of a natural cycle of population fluctuations, the transmission of zoonotic diseases among human populations becomes something to predict and anticipate, a view that further emphasizes human mastery over those very human-animal interactions that smuggle along the threat of disease.

Despite the growing dominance of this ecological view, the approach also attracted criticism and derision, especially when rodent outbreaks and plague disease continued to riddle the economic activities of colonial settlers. In a complaint letter sent by a British barrister living in Mwanza during an outbreak of plague, he jokingly criticized the official obsession with an ecological approach. ‘Having some knowledge of present time Bureaucratic Methods,’ he wrote to the provincial Senior Medical Officer, ‘I expect [the Director of Medical and Sanitation Services] has asked you to furnish a scientific treatise on the Origin of the Flea and its present day method of propagating its species … or something equally futile and soothing to the Official Mind.’Footnote94 Little did he know that this ‘futile and soothing’ approach of understanding disease and animal population in ecological terms would, by the end of the twentieth century, become the dominant view.

Conclusion

The increasingly ecological approach to rodent outbreaks and plague disease in colonial Tanganyika represented a wider, gradual shift in the biological sciences towards multi-causal and systematic understandings of infectious diseases, their animal vectors, and the environment.Footnote95 The rodent and plague outbreaks of 1931 and their repercussions in colonial Tanganyika present an interesting case study of the application of ecological frameworks in understanding animal population and disease.Footnote96 Indeed, coming merely four years after the publication of Elton’s Animal Ecology, discussions in 1931 among colonial officers in Tanganyika about what to do about rodents and plague confirm how quickly such ecological frameworks had travelled from the metropoles of empire. Colonial officers in Tanganyika gradually moved from a view that prioritised 'ecological interrelations' to one where those interrelations increasingly included studies of population dynamics, endemicity and social organisation. These efforts to control rodent pests and plague reinforced scientific interest in population and disease ecology, many of which would later emerge as dominant approaches in epidemiological and animal population control efforts. It was not until 1938, for instance, that animal population ecology research would take hold as part of plague and rodent control efforts in South Africa.Footnote97

In colonial Tanganyika, ecological frameworks became a tool of the state to order, improve, and govern society. They informed methods for controlling pests, increasing agricultural output, managing epidemics, and extending the reach of the state into the everyday lives of its subjects. The eradication and later attempts at control of rodent outbreaks and plague was thoroughly entangled with colonial notions of development and modernity. The state sought to change local ways of life as solutions to the rodent problem through the use of propaganda, public health campaigns, and the enforcement of new laws. These efforts were not unique to Tanganyika. Along with South Africa, Malaya, and India, Tanganyika was an experimental node in an imperial project of rodent control.Footnote98 The history of colonial rodent control in Tanganyika also helps inform how historians of science might approach ongoing research into ecology in the global South today. The long-term trap-and-release study of Mastomys sp. field mice conducted by W. Victor Harris, for instance, continues to shape current research at the Sokoine University of Agriculture (SUA) Pest Management Centre based in Morogoro town.Footnote99

Under British colonialism, the rodent became more than just a biological organism whose behaviours, reproductive cycles, and ectoparasites needed to be studied. The presence of rodents upended stable notions of private property and sanitation, threatening disease and destruction by trespassing into farms, granaries, stores, train wagons, and onto ships.Footnote100 By taking on an ecological view that incorporated people into a natural rythm of interrelated rodent, flea, and disease outbreaks, these early rodent studies justified colonial intrusion into regulating the habits and cultural practices of African subjects. This new science of ecology recognised a connection between humans and their natural environments, a view that the colonial state used to rationalise confining Africans to their purported ecological homelands while forcing modernising changes onto their ways of life.

The rodent, as constituted through colonial state policy and ecological frameworks to disease and outbreaks, becomes a figure for reordering society in the colonies. The presence of a rodent, in the hands of colonial health and agricultural officers, came to distinguish between ‘native’ and European ways of life. Tanganyikan houses, farming practices, and sanitary habits were identified with the rodent and were thereby subject to new regulations that sought to enforce greater barriers between people and rodents while assimilating them into a dense network of ecological relations. As rodent populations, disease outbreaks, and human activity became gradually naturalised through ecological frameworks that explained their concurrence, it was soon left to colonial governance, or so the imperial argument goes,to keep rodents at bay.

Acknowledgements

Research leading to this article was funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation (No. 9465) and the British Institute in Eastern Africa. I would like to thank Harriet Ritvo and Kenda Mutongi for comments on an earlier version of this article. This article has further benefited from remarks offered by Jamie Lorimer at the More-Than-Human Seminar Series at the University of Oxford, and those offered by Megan Raby at the History of Science Annual Workshop at Princeton University. I also thank the anonymous reviewers for their incredibly helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 TNA J.10/12704/1037/6. Telegram from Director of Agriculture to Chief Secretary, 26 September 1930.

2 TNA 12704/1037/18-19. Letter from Director of Agriculture to Chief Secretary, 27 January 1931.

3 For a history of the ‘Danysz virus’ and its relation to population ecology and the control of rodent pests, see Lukas Engelmann, “An Epidemic for Sale,” Isis 112.3 (2021), 439–60.

4 TNA 11901/v1/30-32. Report from Senior Health Officer, Northern Province to Director of Medical and Sanitation Services, 11 January 1931.

5 Myron J. Echenberg, Plague Ports: The Global Urban Impact of Bubonic Plague, 1894–1901. New York: New York University Press, 2007, pp. 7–9.

6 See, for e.g., J. I. Roberts, ‘The Endemicity of Plague in East Africa’, East African Medical Journal, 12 (1935), 200–219; A.S. Msangi, ‘The Surveillance of Rodent Populations in East Africa in Relation Plague Endemicity’, Dar Es Salaam University Science Journal, 1 (1975), 6–20; Rhodes Makundi, T.J. Mbise, and Bukheti S. Kilonzo, ‘Observations on the Role of Rodents in Crop Losses in Tanzania and Control Strategies’, Beitrage Zur Tropischen Landwirtschaft Und Veterinarmedizin (Journal of Tropical Agriculture and Veterinary Science), 29 (1991), 465–74; Bukheti S. Kilonzo, Julius Mhina, Christopher Sabuni, and Georgies Mgode, ‘The Role of Rodents and Small Carnivores in Plague Endemicity in Tanzania’, Belgian Journal of Zoology, 135.(supplement) (2005), 119–25; Michael H. Ziwa, Mecky I. Matee, Bernard M. Hang’ombe, Eligius F. Lyamuya, and Bukheti S. Kilonzo, ‘Plague in Tanzania: An Overview’, Tanzania Journal of Health Research, 15 (2013), 252–58; Mari K. Webel, The Politics of Disease Control: Sleeping Sickness in Eastern Africa, 1890-1920. New African Histories Series. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2019, particularly Chapter 3.

7 John Iliffe, A Modern History of Tanganyika (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979), p. 343.

8 TNA J.10/12704/1037/141-142. Director of Agriculture, ‘Statement on the Reduced Output of Cotton from the Kimamba Area,’ n.d. 1 cental of cotton is equivalent to 1 pound of cotton.

9 Peter Crowcroft, Elton’s Ecologists: A History of the Bureau of Animal Population (University of Chicago Press, 1991), pp. 11–12. See also Jones, Susan D. “Population Cycles, Disease, and Networks of Ecological Knowledge.” Journal of the History of Biology 50 (2017), p. 374.

10 See Mark Honigsbaum, ‘“Tipping the Balance”: Karl Friedrich Meyer, Latent Infections, and the Birth of Modern Ideas of Disease Ecology’, Journal of the History of Biology, 49.2 (2016), 261–309 and Anderson, Warwick, ‘Natural Histories of Infectious Disease: Ecological Vision in Twentieth-Century Biomedical Science’, Osiris, 19 (2004), 39–61.

11 John Phillips, "The Biotic Community," The Journal of Ecology 19 (1931).

12 Peder Anker, Imperial Ecology: Environmental Order in the British Empire, 1895-1945 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), p. 121.

13 Jules A. Skotnes-Brown, "Pests, Knowledge and Boundaries in the Early Union of South Africa: Categorising, Controlling, Conserving," PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge (2020), p. 181.

14 Helen Tilley, ‘Ecologies of Complexity: Tropical Environments, African Trypanosomiasis, and the Science of Disease Control in British Colonial Africa, 1900-1940’, Osiris, 19 (2004), 21–38.

15 Karen Sayer, ‘The ‘Modern’ Management of Rats: British Agricultural Science in Farm and Field during the Twentieth Century’, BJHS Themes, 2 (2017), 235–63.

16 TNA J.10/12704/1037/88. Letter from Director of Agricultural Research Station at Amani to Chief Secretary, 20 January 1932; TNA 11901/v1/27-29. Letter from Acting Director of Medical and Sanitary Services to Provincial Commissioner Northern Province, 11 December 1930.

17 Harriet Ritvo, Noble Cows and Hybrid Zebras: Essays on Animals and History (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010), and The Platypus and the Mermaid, and Other Figments of the Classifying Imagination (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1997); Timothy Mitchell, Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), pp. 19–53.

18 Etienne Benson, ‘Animal Writes: Historiography, Disciplinarity, and the Animal Trace’, in Making Animal Meaning, ed. by Linda Kalof and Georgina M. Montgomery (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2011), pp. 3–16. See also Carlo Ginzburg, ‘Clues: Roots of an Evidential Paradigm’, in Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), pp. 96–125.

19 Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Beacon Press, 1995).

20 See Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga, ‘Vermin Beings On Pestiferous Animals and Human Game’, Social Text, 29 (2011), 151–76.

21 Many of the cotton growers in Kimamba, outside of Morogoro, were Greek. There were also a number of Italian and Afrikaner growers, the latter having left South Africa as refugees of the Boer War. They employed Tanganyikans as laborers. See TNA J.10/12704/1037/133 for newspaper cutting (possibly from The Tanganyikan Standard), ‘Killed by Rats,’ 1932. On non-British settlers in Tanganyika, see Iliffe, Tanganyika, pp. 142–43.

22 Ann Laura Stoler, Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010), p. 4.

23 TNA J.10/12704/1037/14, Letter from Ag. Director of Agriculture to Chief Secretary, 6 October 1930.

24 TNA J.10/12704/1037/15, Handwritten notes.

25 TNA J.10/12704/1037/16, Handwritten notes. This approach characterised the system of indirect rule in Tanganyika Territory.

26 TNA J.10/12704/1037/26, Telegram from Secretary of State, London to Governor, Dar es Salaam, 6 Feb 1931.

27 TNA J.10/12704/1037/25, Circular from Ministry of Health, transmitted to Tanganyika, 12 Jan 1931.

28 TNA J.10/12704/1037/37-40, Letter from Acting Director of Medical and Sanitation Services to Director of Agriculture, 8 May 1931.

29 TNA J.10/12704/1037/52, Newspaper cutting, ‘Kimamba Infested by Rats,’ The Tanganyika Standard, 1 Oct. 1931.

30 TNA J.10/12704 /1037/46-47, Letter from Director of Agriculture to Chief Secretary, 15 Sept. 1931.

31 TNA J.10/12704 /1037/61, Memorandum of the Chamber of Commerce, Dar es Salaam, 25 November 1931.

32 TNA J.10/12704/1037/51, Newspaper cutting, ‘Rats,’ The Tanganyika Standard, 1 Oct. 1931.

33 TNA J.10/12704/1037/70, Letter from Tanganyika Ginneries’ Association to Chief Secretary, 11 Dec 1931.

34 TNA J.10/12704/1037/52, Newspaper cutting, ‘Kimamba Infested by Rats,’ The Tanganyika Standard, 1 Oct. 1931.

35 TNA J.10/12704/1037/46-47, Letter from Director of Agriculture to Chief Secretary, 15 Sept. 1931.

36 TNA J.10/12704/1037/50, Letter from Acting Director of Medical and Sanitary Services to Chief Secretary, 24 Sept. 1931.

37 TNA J.10/12704/1037/58-59. Letter from Director of Agriculture to Chief Secretary, 9 November 1931.

38 TNA J.10/12704/1037/52a. Handwritten note. Author and date unknown but probably end of September 1931.

39 W. M. Nowell, who was director of Amani at the time, had an ongoing interest in pursuing longer-term investigations into the 'inter-relations' of geology, soil, climate, plants, animals, and people. See Helen Tilley, Africa as a Living Laboratory: Empire, Development, and the Problem of Scientific Knowledge, 1870-1950 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), p. 130.

40 TNA J.10/12704/1037/67-68. Letter from Director of East African Agricultural Research Station to Chief Secretary, 3 December 1931.

41 Apolo Kaggwa, The Kings of Buganda, trans. and ed. M. S. M. Kiwanuka, Historical Texts of Eastern and Central Africa 1 (Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1971), pp. xxiv–xxvii.

42 Ibid., 175.

43 Robert Pickering Ashe, Two Kings of Uganda: Or, Life by the Shores of Victoria Nyanza (S. Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, 1889); W. J. Simpson, Report on Sanitary Matters in the East Africa Protectorate, Uganda and Zanzibar (1914). It is important to note that Mari K. Webel, The Politics of Disease Control: Sleeping Sickness in Eastern Africa, 1890-1920 (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2019), pp. 126-32, argues that ‘kaumpuli’ in the Oluganda language (or 'rubunga' in the Oluhaya language) describes a range of related social and bodily phenomena, including swollen glands, a symptom common to African trypanosomiasis or sleeping sickness as well as plague caused by Yersinia pestis. The direct translation of ‘kaumpuli’ as plague first emerged in colonial missionary writings. Kaumpuli should not be seen as designating a specific disease or etiology but as a broader intellectual framework among the Ganda for explaining epidemiological changes in relation to changes in the environment, politics, and society of the western lake region at the end of the nineteenth century.

44 See Msangi, ‘The Surveillance of Rodent Populations in East Africa in Relation Plague Endemicity’; Roberts, ‘The Endemicity of Plague in East Africa.’ For German sources of plague disease occurring in these areas at the end of the nineteenth century, see Zupitza, ‘Die Ergebnisse der Pestexpedition nach Kisiba am Westufer des Victoriasees 1897/98’, Zeitschrift für Hygiene und Infectionskrankheiten 32 (1899), 268–94; and Robert Koch, ‘Reiseberichte über Rinderpest, Bubonenpest in Indien und Afrika, Tsetse- oder Surrakrankheit, Texasfieber, tropische Malaria, Schwarzwasserfieber (1898)’ in Gesammelte Werke von Robert Koch 2, part 2 (Leipzig: Verlag von Georg Thieme, 1912), 688–742, cited in George D. Sussman, ‘Scientists Doing History: Central Africa and the Origins of the First Plague Pandemic’, Journal of World History, 26 (2015), 325–54.

45 J. Isgaer Roberts, ‘Plague Conditions in an Urban Area of Kenya (Nairobi Township)’, The Journal of Hygiene, 36 (1936), 467–84; Milcah Amolo Achola, ‘Colonial Policy and Urban Health: The Case of Colonial Nairobi’, Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 36–37 (2001), 119–37.

46 Monica H. Green, ‘Putting Africa on the Black Death Map: Narratives from Genetics and History’, Afriques. Débats, Méthodes et Terrains d’histoire, 9 (2018). Currently, there has not hitherto been an attempt to study a large enough sample of genetic sequences of Y. pestis in East Africa that would provide additional evidence that indicate when phylogenetic branching might have occurred. For a preliminary genetic study of Y. pestis in Tanzania, see Michael H. Ziwa, Mecky I. Matee, Bukheti S. Kilonzo, and Bernard M. Hang’ombe, ‘Evidence of Yersinia Pestis DNA in Rodents in Plague Outbreak Foci in Mbulu and Karatu Districts, Northern Tanzania’, Tanzania Journal of Health Research, 15 (2013), 152–7.

47 Plague in Tanganyika Territory: Notes on the History, Dangers, and Prevention of the Disease (Dar es Salaam, 1931), pp. 2–3.

48 Bukheti S. Kilonzo and J. I. K. Mhina, ‘The First Outbreak of Human Plague in Lushoto District, North-East Tanzania’, Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 76 (1982), 172–7; Bukheti S. Kilonzo and R. S. Mtoi, ‘Entomological, Bacteriological and Serological Observations After the 1977 Plague Outbreak in Mbulu District, Tanzania’, East African Medical Journal, 60 (1983), 91–97; Bukheti S. Kilonzo, ‘Plague Epidemiology and Control in Eastern and Southern Africa during the Period 1978 to 1997.’, The Central African Journal of Medicine, 45 (1999), 70–76; Michael H. Ziwa et al., ‘Plague in Tanzania’.

49 Present-day Arusha and Kilimanjaro Regions.