?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Antonino Saliba, a sixteenth century cartographer hailing from the Maltese island of Gozo, published a map in 1582 espousing his cosmology. Its popularity at the time is attested via the multiple editions and copies that were produced in Europe. Numerous sky phenomena, amongst them comets, are portrayed in the map. This study presents a detailed analysis of Saliba's treatment of these phenomena, following the first comprehensive translation of the map's text to English. It elucidates the sources that Saliba used, clarifying and shedding further light on the views he held. Where possible, the comets mentioned by Saliba are identified and explained. Besides showing how Saliba wholly conformed to the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic representation of the world, in which respect he was quite orthodox, it is also shown for the first time that his work is significantly derived from previous and contemporary sources.

1. Introduction

Antonino Saliba – who has been called ‘the first Maltese scientist’Footnote1 – was a learned man from Gozo, the sister island of Malta, who flourished in the sixteenth century, with Maltese historian Ġan Franġisk Abela (1582–1655) including him in his list of Maltese people of note. That he was Gozitan is not only declared by Saliba himself, but also described in a personal letter from Gozitan historian Giovanni Pietro Francesco Agius de Soldanis (1712–1770) to Ignazio Saverio Mifsud (1722–1773),Footnote2 the latter explaining that he himself was related to Saliba from his mother's side.Footnote3 The dates of both Saliba's birth and death are as yet uncertain.Footnote4 Abela wrote that Saliba was ‘a professor of various liberal sciences’, that he was ‘particularly famous, and very expertly in astrology’, and that he ‘wrote on meteorological impressions excellently’ in a work dedicated to the Grandmaster – Hugues Loubenx de Verdalle.Footnote5 We shall briefly refer again to this work later; the main subject of this study, however, is an earlier opus which Saliba is most well known for – an exquisitely drawn mapFootnote6 showcasing his cosmography (see ).

Figure 1. The 1582 map of Antonino Saliba. (Image: Herzog August Library Wolfenbüttel, Signature K 3,6; License: CC BY-SA 4.0. https://kartenspeicher.gbv.de/item/hab_mods_00007813)

The map was first published in Naples in 1582, with the engraved illustrations being by Mario Cartaro.Footnote7 The lengthy titleFootnote8 describes it as being

A new figure of all the things that exist and are continuously generated in the Earth and above in the air, composed for the Magnificent Antonino Saliba, a Maltese from Gozo, Doctor in Philosophy, Theology and in Canon and Civil Law, for the universal benefit of those who desire to know the hidden secrets of nature with its declaration.Footnote9

Besides the title of ‘doctor’ ascribed to Saliba in the title, through his own words we also know that he served as commissioner of tithes for Malta.Footnote10 Writing in 1846, Rev. Francesco Caruana Dingli also described that Saliba was sent as ambassador to the king of France, and later Sicily, and was made knight of honour and Capo della Militia.Footnote11

The map is an eclectic blend of cosmography, cosmology, religious motifs, and astrological belief – presented in a dense portrayal of the Earth surrounded by atmospheric phenomena. A number of illustrations are accompanied by a written description, and some are also referenced by a number in the accompanying text, which (excluding the dedication section and the introduction, which is not titled), is grouped into fifteen sections titled as follows:

| (1) | Of Earth, and of hell | ||||

| (2) | Of demons and of the punishments suffered by the souls in hell | ||||

| (3) | Of the limbo of children | ||||

| (4) | The third circle and the purgatory | ||||

| (5) | Of the punishments, and fire of hell, and of the purgatory | ||||

| (6) | Of the limbo that of old was of the patriarchsFootnote12 | ||||

| (7) | In which part and place of hell descended the spirit of Christ | ||||

| (8) | Seven are the ages of the world | ||||

| (9) | Of the sea, and its salinity | ||||

| (10) | Of air, and its parts, called by philosophers regions | ||||

| (11) | Of the effect that the sun has in the earth, the sea, and the air | ||||

| (12) | Second region of the air | ||||

| (13) | The remedies against lightning | ||||

| (14) | Third region of the air | ||||

| (15) | Of comets and other similar ignited impressions | ||||

Despite the popularity and importance of the map in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, detailed published analyzes about it for an English-reading audience are scant. Three Maltese publications, two of which are written in the Maltese language (and therefore not accessible to a wide readership), have previously looked at its cartographic aspects and touched upon its general themes.Footnote13 Other works available in English are scarce,Footnote14 and to the author's knowledge, a treatment of the map from an astronomer's (as opposed to a cartographer's) perspective is also missing. To address these lacunae, on the basis of a close reading and comprehensive translation to English, in this work I thoroughly explore the sky phenomena portrayed in Saliba's map, presenting a detailed analysis of the work from an astronomer's point of view, paying close attention to the state of knowledge in Saliba's time, particularly as it pertains to the medieval and renaissance formulation of Aristotelian meteorology, for it is against this backdrop that the work should be viewed. Saliba's mode of expression – a map intricate and ostentatious – sits within the sphere of renaissance ‘visual encyclopedism’,Footnote15 with Saliba's grandiose ambition being to summarize the knowledge of ‘all the things’ known about the world, be they inside the Earth or above.Footnote16

The map is divided into nine concentric zones. The core area – evocative of Dantesque imagery – depicts the inferno deep within the Earth's belly, with Lucifer in the very middle surrounded by demons and damned souls. The surrounding three layers relate to the limbo of children (the limbus infantium or limbus puerorum of Catholic theology), the purgatory, and the limbo of the patriarchs (limbus patrum), where those who died in God's friendship despite their sins would lie in waiting until Christ's salvation. Here, Saliba makes clear reference to the idea of the harrowing of hell by Christ (‘In che parte e lvogo dell'inferno discese l'anima di Christo’), an aspect of Christian theology very much espoused in medieval dramatic literature.

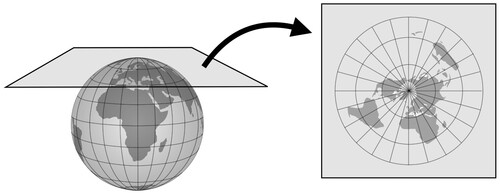

The Earth's surface is described in the fifth zone – juxtaposed centrally such that it is flanked by the aforementioned religious motifs on one side, and a fantastical representation of the heavens on the other. From this particular layer we may glean some insight into Saliba's mathematical and cartographic prowess. He employed a polar azimuthal projection (see ), an uncommon system for the time, but not unique to Saliba's map.Footnote17 This allowed him to portray the earth's surface in one uninterrupted circular band with minimal distortion, particularly because the map is restricted in latitude, spanning the range between the equator to around 50 degrees.Footnote18 In the subsequent (6th to 8th) zones, Saliba treats a number of sky phenomena, which will be the main focus of this paper.

Figure 2. Saliba employed a polar azimuthal projection. This entails projecting the globe (but oftentimes, in practice, only a single hemisphere) onto a flat plane centred on and perpendicular to the Earth's axis. Distortion increases with distance away from the central point. However, Saliba restricted his map to the region spanned by the equator and 50 degrees latitude, and therefore the distortion is limited. (Figure by the author.)

2. Saliba's declared cosmology

In the very opening line of the introduction, Saliba calls the map a ‘Machina del Mondo’ that ‘contains in it all the things that God created for his glory’.Footnote19 With the phrase ‘machina del mondo’ (machine of the world), Saliba is alluding to the concept of the machina mundi. A phrase already used in classical antiquity by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius,Footnote20 in medieval times, the notion of a machina was commonly used to represent the world as an ordered system.Footnote21 We encounter it, for example, in the Tractatus de sphaera – the highly influential, early thirteenth century treatise by Johannes de Sacrobosco. In this outlook, the universe is conceived as a machine of sorts, the secrets of which are to be probed. The metaphor would be used, amongst others, by Copernicus,Footnote22 and would eventually come to assume a mechanistic meaning. Saliba next proceeds to describe the composition of the world. In so doing, not only does he leave us in no doubt that he adheres to a wholly Aristotelian and Ptolemaic worldview, but we may also discern that Saliba's introductory text owes much to Sacrobosco's.

Saliba declares that the world is divided in two parts – the ‘elementary’ that was sublunar, and the ‘celestial’ situated above the fire (in reference to the sphere of fire posited to exist below the moon in Ptolemaic and Aristotelian astronomy). The elementary is divisible in four elements which could be generated and corrupted: earth, water, air, and fire. Such a division in a set of four classical elements dates from pre-Socratic times, specifically in the proposal of Empedocles, who called them the ‘roots’, with Aristotle incorporating Empedocles' idea in his own cosmography. Saliba continues that the light elements proceeded upwards in their motion, the heavy ones downwards.Footnote23 And this machine of the world maintained itself because of their transmutation, and the motion of the heavens.Footnote24 Saliba writes that ‘all [spheres] are mobile except for the Earth, which, being restricted in itself and placed in the lowest place, lies at the centre of the circumference of the heaven that rotates around it’; the round Earth is further described as immobile and still, and ‘almost a point in respect to the entire heaven’.Footnote25

Moving on to the celestial, Saliba remarks that philosophers called the heaven (‘cielo’) the ‘fifth essence’,Footnote26 and it moved from east to west, returning to the east in a cycle of twenty four hours.Footnote27 The planets, on the other hand, moved from west to east.Footnote28 Saliba declares that that there are 11 heavens; in order, these pertained to the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, stars, crystalline sphere, first mover, and Empyrean heaven.Footnote29 This is an important description, as it consolidates the cosmology that Saliba subscribes to. By way of comparison, one may compare Saliba's scheme to that found in Petrus Apianus' very popular Cosmographicus Liber of 1524Footnote30 – the agreement is perfect. The heavens, writes Saliba, were ‘neither elements nor composed of elements, neither heavy nor light, neither hot, nor cold’; they were ‘lucid, transparent, and ornate with beautiful lights and stars’.Footnote31 Thus, Saliba lays the general foundations for the world prior to considering the particulars that are to be found within the zones that are treated in the map.

The similarity of Saliba's introduction to the structure – in places, even the text – of Sacrobosco's introductory chapter is very evident. One may observe how Sacrobosco states that the ‘machine of the world is divided into two: in the ethereal and the elementary region’,Footnote32 citing the authority of Aristotle's Meteorologica in presenting the Earth at the centre surrounded by water, air, and fire up to the sphere of the moon. Sacrobosco likewise speaks of the corruptible nature of the elements, and in mentioning the lucid and immutable ethereal, he remarks, just like Saliba does, that it was ‘called Fifth Essence by the philosophers’.Footnote33 He lists the nine spheres (up to that of the fixed stars), speaks of the revolutions of the heavens from east to west, and the planets' motion. Right from the introduction, therefore, one understands that Saliba is presenting the established Aristotelian system of the world, as was taught and commented upon for many years in Europe via the popular elementary textbook of Sacrobosco.

Outside the map itself, in each of the four spandrels, we find information about solar and lunar haloes and eclipses. In the top spandrels, we read of haloes being a prognostic for the weather; be it serene or windy. Echoing Theophrastus, we read that black signifies rain. In the bottom left spandrel we find a correct explanation of lunar eclipses being the result of their slipping into the Earth's shadow. And in the bottom right spandrel we read a correct explanation of solar eclipses occurring when the moon comes in between the Earth and the sun.

3. The sky phenomena in Saliba's map

3.1. Aristotelian meteorology in the middle ages and renaissance

In setting the context to Saliba's treatment of phenomena of the sky, it is necessary to first delineate the boundaries of the word ‘meteorologia’ in the middle ages/renaissance. During this period, meteorology lay within the philosophical domain, and bore very little resemblance to the modern-day understanding of the term.Footnote34 Confined to the Aristotelian sublunary realm, meteorology primarily dealt with observed phenomena's material causes – and some of the topics it encompassed, like meteors and comets (then thought to be sublunary), nowadays lie within the purview of astronomy.

Aristotle's works were widely commented upon, his Meteorologica being no exception.Footnote35 Among the works treating Aristotelian meteorology we find the mid-sixteenth century In libris Aristotelis meteorologicis commentaria by Agostino Nifo (c. 1473–1538/45), the 1556 commentary by Francesco Vimercato (1512–1571),Footnote36 the 1563 Dubitationes in quartum Meteorologicorum librum by Pietro Pomponazzi (1462–1525),Footnote37 the LectionesFootnote38 by Ludovico Boccadiferro (1482–1545), and the 1582 I meteori by Cesare Rao (1532–1588).Footnote39

Besides the examination of Aristotle's meteorology by such works written in Latin, its divulgation proceeded via a tradition of volgarizzamento, that is to say a vernacular dissemination in the Italian language,Footnote40 of which Saliba's effort may be viewed to form part. Such texts include the fourteenth century, Florentine, La Metaura;Footnote41 the 1537 Dialogi of Antonio Brucioli (c. 1498–1566);Footnote42 the manuscript from the first half of the sixteenth century by Benedetto Varchi (1502/03–1565) titled Comento sopra il primo libro delle Meteore d'Aristotile;Footnote43 and the 1542 Meteorologia by Sebastiano Fausto da Longiano (1502–1565),Footnote44 amongst others.

That Saliba was well versed in such contemporary literature is immediately evident from a comparison of his work with, for example, da Longiano's. The similarities run the gamut from the division of the air in three regions, to the discussion of the rugiada, brina and manna, and from nocturnal fires, falling stars, and apertures in the sky, to lamps and comets.Footnote45 Thus, Saliba may be seen as one figure in a long tradition of communicators and popularizers of Aristotle's Meteorologica, his work being particularly conspicuous on account of its visually striking nature.

3.2. The three regions of the air

In line with the medieval/renaissance reading of Aristotle's meteorology, Saliba explains that the air is a ‘body that fills every place, and according to Aristotle is divided in three parts, or regions.’Footnote46 The first, writes Saliba, starts from the Earth and water, ending where the reflections of the sun's rays terminate. The second begins where there is a lack of said reflection, and finishes at the top of the world's highest mountains (such as Mount Olympus, Mount Athos in Macedonia, and the Caucasus mountains, described to surpass eighty miles in height). The third extends from the top of said mountains, rising all the way to the moon, and ends at the concavity of fire (‘co[n]cavo del fuoco’), that is to say, the inner surface of the sphere of fire.Footnote47 Saliba explains that these three regions are not only distinct from each other, but also differ in quality. The air, ‘of its own nature, is warm and humid’, writes Saliba, but acquires other qualities. Thus, the first region (which is the closest to the Earth) varies depending on the four seasons of the year, the second ‘is always cold and humid, both because it is distant from the sphere of fire from the upper side, and again from the reflection of the solar rays from the lower part’, it being described as a receptacle for the humid vapours that rise from the earth and the sea – ‘the material of rain and other similar humid impressions’.

3.3. The effect of the sun upon the earth, sea, and airs

In this section, Saliba expounds upon the nature of vapours, exhalations, and some commonly discussed phenomena. He begins by differentiating between the terms ‘vapour’ and ‘exhalation’, essentially following Aristotle.Footnote48 The former is ‘warm and humid’, and is described to be ‘water in potential’ (‘acqua in pote[n]za’). The latter is warm, dry, and smoky (‘fumosa’), and quick to ignite, being fire in potential. The ‘vapour is the material of humid impressions’, writes Saliba, examples being dew (‘ruggiata’Footnote49), frost (‘brina’), manna (Illustration No. 4), rain, and other such, which are generated in the first region of the air. The exhalation is the material of all the ignited impressions, such as shooting stars (‘stelle volanti’), comets, carts of fire, flying dragons and other similar,

. . . as seen in the third region of the air where they are generated and are ignited due to the motion of the Sphere of fire and the celestial bodies, and according to the various disposition and quantity of the exhalation – more, or less, lit – they appear in the airs in many diverse images and forms of ignited bodies . . .Footnote50

From their appearance, continues Saliba, they acquire the name of ‘bearded comet’ (‘cometa barbata’), ‘hairy’ (‘crinita’), ‘tailed’ (‘caudata’), ‘horn of fire’ (‘corno di fuoco’), ‘flying dragon’ (‘dragho vola[n]te’), ‘sword’ (‘spada’), ‘horn’ (‘corno’), or ‘star’ (‘stella’). Such impressions, explains Saliba, ‘are almost all the same thing’, their being made of the same matter; smoky, hot, and dry exhalations are not different from each other. Should the exhalation be ‘small and rare, such that it cannot rise upwards’,Footnote51 then it stays in the vicinity of the earth, and ‘it ignites from the motion of the air’. Saliba writes that this is the cause for ‘various and diverse small flames and scintillations of fire, sometimes in the guise of lit candles’,Footnote52 which are described to appear at times of good weather, and seen in many places in the first region of the air.

Following an explanation of vapours and the phenomena that arise from them (such as the aforementioned dew and manna, which we shall not be concerned with here), Saliba continues to write of exhalations. At times, writes Saliba, ‘wanting to rise up’, but not being able to pass beyond the second region of the air, an exhalation will return to the lower, and as it descends encounters the other that was rising, colliding to cause winds. At times, ‘these exhalations ignite in the guise of a lit torch’; sometimes as two, ‘called by philosophers Castor and Pollux’,Footnote53 which is ‘a kind of fire’ that moves ‘close to earth, at times towards valleys, rivers, and other similar places’. At times these fires appeared at night atop cages and masts of ships, ‘like little lights, and on the shoulders of mariners’, these being called ‘S[an]to Hermo’ and ‘S[an]to Nicola’.Footnote54 Here, Saliba is referring to Saint Elmo's fire. (When there is a difference in charge between a rod- or pole-shaped object, such as between a ship's mast and the surrounding air, an electrical discharge may occur when the air becomes ionized, in what is termed ‘corona discharge’, the latter causing a glowing plasma. The phenomenon of Saint Elmo's fire is a manifestation of this mechanism, which is variously known as ‘Saint Hermes’ fire', ‘Saint Helen's fire’, and even ‘Saint Peter's lights’.) Saliba explains this to be due to viscous exhalation that exits the ship and moves in the air, ‘escaping the cold of night, now here, now there’, and being ‘greasy and smoky’ (‘untuosa, e fumosa’), it quickly ignites, and through the agitation of the winds attaches ‘now to the cages of the ship, now to the stern’. Alluding to a commonly held belief about this phenomenon, Saliba writes, ‘This fire is called by the ancients the star of Helen, a most dangerous sign to mariners, and always appears before fortune.’Footnote55

At times, describes Saliba, it appeared as if the whole ship was ablaze, the reason being that the exhalations would rise from all the ship and ignite in the airs. Similar to this fire, he continues, is that which was found on hairs and drapes. Saliba also treats red-coloured rain: ‘At times, the vapour having been converted to rain, it falls very bitter, and of a red colour, like blood’.Footnote56 The explanation provided is that a salty, bitter, and red perspiration could be generated in a cloud, and not having been ‘well cooked’ (‘ben cotto’) by the sun, ‘a certain salty, bitter, red’ perspiration forms that gives rain its blood colour. Sometimes other things were generated in the airs ‘according to the various and diverse disposition of the matter’, with Saliba listing worms, pieces of meat, blood, milk, stones, wool, iron, and frogs. The spontaneous generation of living creatures, already established in antiquity, and the raining of objects and animals (such a list is read in Pliny, Naturalis Historia II.57) remained a widely held belief in the middle ages and persisted even well beyond.Footnote57 Such imagery of falling material and living creatures from the sky can also be subtly suggestive of the account of the Plagues of Egypt in the book of Exodus; in this respect, Saliba may be seen to be providing natural explanations for such events via a mechanism in the airs that could create a variety of things. This would still fit within the narrative of a ‘Machina del Mondo’, as willed by God.

3.4. The sixth zone: the first region of the air

This zone focusses on a number of atmospheric phenomena. We see depicted here clouds, rain, lightning, shooting stars (‘stelle cadente’), ‘flames of fire that look like torches’ (‘fiam[m]e di fuoco a guisa di torche’), and, citing Aristotle, ‘Leaping goats’ (‘Capre saltati’ [sic]). Indeed, this is practically a colourful rendition of Aristotle's Meteorologica I.4 devoted to ‘the appearance of burning flames in the sky, of shooting stars and of what some people call “torches” and “goats.”’Footnote58 Of these, Aristotle writes that they ‘are the same thing and due to the same cause, and only differ in degree’. It is therefore no surprise that Saliba has them all contained within the same region. Aristotle explains such phenomena in terms of exhalations rising from the earth, one kind ‘vaporous in character’, the other ‘windy’, ‘dry’ and ‘hot’.Footnote59 This is echoed in Saliba's own description of the generation of ‘leaping goats’ and ‘shooting stars’, where he speaks of such rising exhalations and their character. And just as Aristotle tells us that shooting stars are produced ‘if the parts of the exhalation are broken up small and scattered in many directions’, in Saliba we read, ‘when the exhalation is dispersed and divided in multiple parts . . .’ (‘quando la esalatione sara dispersa e divisa in piu parti . . .’), providing both Aristotle's and Pliny's name for them (translated to Italian).

3.5. The seventh zone: the second region of the air

Having risen to the second region of the air ‘by virtue of the sun’, the vapours and exhalations soon fall because of the cold, explains Saliba – partly as rain, and partly as clouds. This seventh zone of the map carries the winds, with each cardinal and intercardinal direction represented by a windface. Three fiery bolts of light (No. 6) are accompanied by a description telling us that ‘these stones or thunderbolts are generated in clouds’.

Amongst the esoteric drawings we come across an illustration of concentric black and yellow rings, accompanied by a legend reading that at times ‘there appears an aperture in the sky’ (‘appare una apertura nel cielo’, referring to a ‘casma’; illustration No. 16). This is directly comparable to passages from Aristotle and Seneca. In Meteorologica, Aristotle spoke of ‘“chasms”, “trenches” and blood-red colours’, generally interpreted to be describing, albeit somewhat abstrusely, the phenomenon of the aurora.Footnote60 Seneca speaks of two phenomena which are likewise interpreted to be referring to aurorae.Footnote61 One is bothyni (wells or trenches), of which Seneca writes: ‘there are “wells”, when there is a surrounding garland, as it were, and inside there is a huge recess in the sky, looking as though a circular cave has been dug out . . .’; another is chasmata (chasms), with Seneca writing: ‘there are “chasms”, when a stretch of the sky has receded and, as it were, gapes open displaying flames deep down.’Footnote62 In Pliny we also read of an opening or yawning of the sky called ‘chasma’.Footnote63 The drawing in Saliba's map would not readily suggest an aurora, but it does fit such descriptions from antiquity. It is quite unlikely that Saliba would have ever observed an aurora himself (on account of their visibility being largely restricted to high latitudes), and his illustration would have to be based on descriptions such as these; by that measure, it would be an adequately faithful depiction. Nevertheless, it appears that it was not aurorae that Saliba was describing when referring to chasms, as we shall have occasion to see in the next section. An adjacent illustration in Saliba's map describes a ‘Mountain of fire’ (‘Monte di fuocho’; No. 17). And a short distance away we see figures playing trumpets (No. 19). In this respect, it is worth noting that Pliny has a passage that speaks of the sounds of armour and trumpets in the sky.Footnote64

Saliba writes that ‘at times with thunder there fall many stones, iron, and other metals’, explained to be generated in the cloud from the ‘residue of the exhalation’. He comments about how there was a difference in opinion about how far into the ground this stone could penetrate: some maintained it was not more than six palms, while others said five feet, ‘as is read in the histories, and particularly in Pliny’.Footnote65 Of this stone, ‘Aristotle did not make mention’, writes Saliba, while Avicenna said that he had seen fall from the sky a dead calf (which is depicted in an illustration). The actual source of this much discussed event in medieval times is Albert the Great, who attributed it to Avicenna.Footnote66 In fact, Saliba himself does mention Albert the Great in the illustration's caption, and here he even attributes the observation to him directly.Footnote67

Saliba makes reference to Averroes' account of Avicenna's report of a great stone that fell from the sky on a serene day in Cordoba.Footnote68 Saliba remarks that it was not an error, in his opinion (‘al mio gioditio’), that in the air there may be generated such a stone, alluding via analogy to the formation of kidney stones through greasy and viscous humour.

3.6. The eighth zone: the third region of the air

‘When the exhalations have risen by virtue of the sun into the third region’, writes Saliba, ‘because of the heat of the place and the motion of the heavens, they soon dilate, now in length, now in breath, now in some way, now in another’.Footnote69 Referring to the naturalists (‘dicono i Naturali’), being hot and dry they ignite and ‘according to the various disposition of the matter they receive various and diverse forms of fire’, referring to the illustrations in the map, which depict comets of the barbata, codata, crinita, and drago volante varieties (Nos. 9–12, respectively). When the exhalation dilates more in length than in width, one spoke of a ‘torch’ (‘face’), ‘firebrand’ (‘tizzone’), or ‘beam of fire’ (‘trave di fuoco’; the Latin term for this was trabs).Footnote70 One may observe that the beams/boards are effectively being equated to torches, similar to what Pliny does. In this respect, this differs from the account of Seneca, who distinguishes between the two.Footnote71 Such a phenomenon appeared, writes Saliba, when Germanicus Julius Caesar held gladiatorial spectacles in Rome, when the Lacedaemonians (i.e. the Spartans) lost the empire of Greece,Footnote72 and when Lucius Aemilius Paullus (‘Paulo Emilio’) warred against King Perseus.

At times, writes Saliba, this exhalation divides in multiple parts, one igniting after the other, likening it to the lighting of fireworks when, ‘during feasts, the fire snaking across the ground lights up mascoli, or let us say, mortaletti’.Footnote73 Following from this analogy, Saliba proceeds to distinguish between ‘flying stars’ (‘stelle volanti’) and ‘falling stars’ (‘stelle cadenti’). Referring to the fireworks analogy, ‘such happens to the exhalation’, writes Saliba, describing how the first part is lit up, then the spent one, proceeding in such a chain until the parts are extinguished. This is how they appear like stars that fly – ‘therefore called stelle volanti’. The ‘falling stars’ on the other hand, are caused when the exhalation, having risen close to the second region of the air, is counter-blown (‘ribatuta’) downwards by the coldness of this place, and in descending so fast it ignites, appearing like a star falling from the sky (Illustration no. 15).Footnote74 A phenomenon similar to this was seen in Saxony in February of the year 148, describes Saliba, continuing that ‘at times it receives the form a pyramid, at times of an aperture, or pit, or let us say, chasm’Footnote75 (No. 16). The latter occurs when, in the air, there is a lit and bright exhalation whose centre is occupied by a cloud that is dark, ‘called by philosophers Assub, or Chasma’, an example being that which appeared ‘in the time of Tiberius Cesare in Germany’.

Saliba describes that ‘At times, the lit exhalation will be great, and copious and its circumference will be covered and circled by a bushy cloud’.Footnote76 This is represented in the air as a ‘Mountain of fire’ (‘Monte di fuoco’; No. 17). Thus occurred at the end of January 1551 in the west, writes Saliba, succeeded by earthquakes in Lisbon where, he continues, more than two hundred houses were ruined and many people died, followed by the cessation of peace amongst Christian princes, and the war of Parma (see ).

When the dark cloud is ‘illustrated and really illuminated by the lit exhalation, according to the various and diverse form of light that it receives’, there could form in the air shapes of ‘various men and armed horses in the act of combat’. At times, continues Saliba, ‘there form two giants of fire with two lances in their hands’ (No. 18), an example of this occurring around the Cimbrian war, ‘with noise and clash of arms and sounds of trumpets’ (No. 19). This was caused when more exhalations were locked between the dense clouds; being oppressed, they exerted force, and exited from a cloud to enter another.Footnote77 At times they encountered each other as they exited and entered, and broke up, creating various sounds in the air, such as trumpets or arms, ‘according to the various and diverse rupture of said exhalations’, with Saliba referring to events in Paludi and Ferrara.

The illustrations in the eighth zone of Saliba's map feature an extensive number of classical titlesFootnote78 translated to Italian, including a horn-shaped comet (‘corno’) called ‘ceratia’ (this was mentioned by PlinyFootnote79); a tailed comet (‘cometa codata’); ‘horse hair’ (‘crini di cavalli’), adding that it was called by philosophers ‘hippeo’ (note that in Pliny, we find a comparison to horses' manesFootnote80); a ‘flying dragon’ (‘drago volante’Footnote81); a bolide; lances (‘lancie’); an ignited lamp (‘. . . cometa a guisa di una lampa accesa’); a pyramidical comet (‘Alle volte la cometa appare in forma di piramide’); a short comet (‘breve senza chiome co[n] raggi e crini’); a dagger (‘cortello’); a barrel (‘pitete’), which derives from Pliny and Seneca;Footnote82 columns (‘colonne’; note that Seneca speaks of ‘columnae flagrantes’, i.e. ‘blazing columns’Footnote83); and ‘beams’ or ‘boards’.

3.7. On comets

For Aristotle, comets commonly form when a volatile exhalation ascends to higher parts of the atmosphere and ‘Wherever then conditions are most favourable this composition bursts into flame when the celestial revolution sets it in motion.’Footnote84 As per the medieval/renaissance understanding of Aristotle, Saliba accordingly describes that a comet was nothing but an exhalation that had risen to the third region of the air, in the guise of a star that had ‘hair’ (‘chioma’). As Pliny had said, writes Saliba, there appeared various types, remarking that Aristotle had mentioned only two: ‘Crinita’, and ‘Barbata, called Pogonias’. Reference in medieval (and later) texts to these classifications from antiquity are very common. As an example, one may compare with what his contemporary, the English writer Thomas Lodge, wrote of comets in his 1596 work, The Devil Conjured: ‘Of these there are two sorts, the one called Crinita, the other Barbata: for so Aristotle tearmeth and distinguisheth them . . .’Footnote85 (going on to cite Pliny as well). As in Saliba's text, this is followed by various examples of comets being portents of calamities, a very widespread belief which we find treated in numerous sixteenth to seventeenth century sources.Footnote86 Continuing to interpret Aristotle's scheme, Saliba writes that a comet appeared when the smoky exhalation ignites near the third region on account of the motion of the heavens. It remained bright as it continued consuming the inflammable material.

As we have seen, the eighth layer of the map, which depicts the third region of the air, is dominated by numerous depictions of comets. The large number of illustrations is needed to explain the various kinds of cometary appearance. That being said, however, one also cannot help but wonder whether Saliba's decision to dedicate such attention to comets may have been influenced by the recent apparition of the Great Comet of 1577 (designated C/1577 V1), a mere five years prior to the publication of the first edition of his work, of which he writes:

And fresh in memory, on the 12th of November of [15]77 around the fifth hour of the night there appeared a comet of great splendour in the west in the sign of Capricorn, and it lasted a total of 7 weeks followed closely by the death of many kings, amongst which, that of the King of Portugal in the Reign of Fez, the death of his Highness in Flanders, where shortly before there appeared many fires . . .Footnote87

We also find this comet mentioned in Maltese author Pietro Paolo Castagna's list of comets that were visible from Malta.Footnote88 It was observed from a great many location, with accounts coming from Peru, Germany, Belgium, the Czech Republic, China and Japan amongst others, variously described as a ‘broom star’, a ‘huge shining spherical mass which vomited fire and ended in smoke’, a ‘terrible great comet’, ‘as distinct as Venus’, and an ‘evil star’.Footnote89 The comet is of particular significance to the history of astronomy, as it was the very first one demonstrated to lie beyond the Earth's atmosphere, upending Aristotelian ideas about these objects.Footnote90 Tycho Brahe himself had observed this comet, and on the basis of his parallax measurements concluded it had to be superlunary (i.e. situated beyond the moon),Footnote91 a conclusion which was agreed upon by contemporary astronomers Michael Maestlin (1550–1631),Footnote92 Cornelius Gemma (1535–1578), and Helisaeus Roeslin (1545–1616).

Just as we may infer that the 1577 comet had an impact upon Saliba, it might be tempting to speculate the same of an earlier apparition – that of the Great Comet of 1556, which Saliba also makes reference to in relation to various calamities, including the death of King Charles V (‘Carlo Quinto’). (Upon sighting it, the emperor is said to have declared, ‘By this dread sign my fates do summon me’,Footnote93 with the comet becoming known as ‘The Comet of Charles V’.) But as we shall see later, there is more to the story of Saliba's reference to this comet (and others) such that reaching this speculative conclusion would be premature.

What is clear is that Saliba, unsurprisingly, emerges as a firm adherent to the then pervasive belief of comets being harbingers of ill fate, describing a number of historical disastrous events held to have an association with some comet apparition. The 1530s-40s saw a methodical approach to the study of past comets,Footnote94 with that century seeing many devote great attention to the probing of past prophecies with a view to comparing them to actual, recent events, fearing that they were living in the end of days.Footnote95 Thus, underneath one of the comets, we find a prominent drawing of a fiery sword, with a legend saying ‘Spada di fuoco’ (‘Sword of fire’). The description reads that in ancient times, a comet in the shape of a sword appeared over Jerusalem;Footnote96 as Saliba also notes in the text, this is in reference to the comet mentioned by the Romano-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, viewed as being portentous of the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE, and which we find depicted in a number of old illustrationsFootnote97: ‘So it was when a star, resembling a sword, stood over the city, and a comet which continued for a year.’Footnote98

Consulting the section on comets in the text, we see how Saliba first refers to some of the hypotheses that had been put forth to explain their nature, such as their being a congregation of stars, or a planet, but quickly proceeds to present Aristotle's theory. This mirrors Aristotle's opening of his own discussion on comets (Meteorologica I.6–7), where he first provides a critique of existing ideas by Anaxagoras, Democritus, the Pythagoreans (that comets are planets), Hippocrates, and Aeschylus prior to presenting his ideas. It is an approach that we also find, for example, in the contemporary Dialogo in materia delle comete, a work published in 1578 by Girolamo Sorboli, and even Tycho Brahe (in the same year).Footnote99

4. Saliba's text and contemporary cometology

We also need to view Saliba's work within the context of preceding and contemporary publications on cometology, particularly in Italy. Broadly speaking, these comprised two categories – pronostici and discorsi; the former was intended for the layperson, providing only a basic account of exhalation theory, and a pedestrian account of comets' ominous nature, while the latter (motivated by the recent emergence of some comet) catered for a more informed audience.Footnote100 Saliba's work can be seen to borrow traits from the former, never delving into technical discussion. (This, after all, was also necessitated by the medium of presentation.)

The illustrations in Saliba's map also exhibit what one might deem to be a fantastical element, as can be seen in the depiction of two anthropomorphised comets in the northwest of the map. The description to one of them reads that ‘there have been seen comets with [an] effigy of a human face with a tail that is not very long’, which is comparable to Pliny's description.Footnote101 The illustrations of the various examples of comets are quite elaborate. Such ornate depictions detailing the variety of cometary appearances are not isolated; indeed they bring to mind such fanciful drawings as those published over a century earlier in Ulm, Germany by an unknown author,Footnote102 or the collection of detailed drawings in Johannes Hevelius' Cometographia, published nearly a century after Saliba's map.Footnote103 The style of illustration and accompanying text, urging awe and terror in equal measure, is not unlike that found in contemporary depictions of comets, such as in the mid-sixteenth century Augsburger Wunderzeichenbuch illuminated manuscript, or the Kometenbuch of 1587.Footnote104 Similarly, the 1557 Prodigiorum ac ostentorum chronicon by Conrad Lycosthenes is replete with imagery of signs – from fantastical comets, stars, and swords in the skies, to halos, triple moons and eclipses, among other phenomena. The 1560 Histoires prodigieuses by Pierre Boaistuau depicts the sword in the sky portentous of Jerusalem's fall (p. 4) and makes mention of bearded and hairy comets, torches, columns, lances, shields, dragons, and multiple moons and suns, including an image of a triple sun (p. 66), and swords and daggers in the sky (p. 68). Chronicles, descriptions, and depictions of such features in the sky are common in medieval/renaissance literature.

For eight of the comets described in the text, Saliba provides a date. In addition to the dates, Saliba also provides information about the comets' appearance, and (as we described earlier) chronicles them as harbingers of very specific happenings.Footnote105 A numbered list of comets mentioned by Saliba is found below; in some cases, the comets are cross-matched against their modern, official designation. (Where clarification or addition was required, I have inserted text in square brackets.)

| (1) | Description: colour of blood. Date: March & April, 1512. Event(s): Death of Pope Julius II [in 1513]. | ||||

| (2) | Description: human effigy; a tail that was not too long; of yellow colour. | ||||

| (3) | Description: shape of a column; without hair. | ||||

| (4) | Description: shape of a half-moon; short rays; in the guise of flames. Date: April, 1521. Event(s): Wars of Rome [Italian War of 1521–1526]; death of Pope Leo X; election of Pope Adrian VI [in 1522]. | ||||

| (5) | Description: similar to a column. Date: reign of Constantine. | ||||

| (6) | Description: ‘quite fiery’ [and possibly also similar to a column; Saliba writes ‘another’, which might imply that this comet was similar to the previous]. Date: 1st of March, 1556. Designation: C/1556 D1 (Great Comet of 1556). Event(s): Wars of Rome; battle of Saint Quentin; wars of Picardy; death of Emperor Charles V [in 1558]; death of Queen Mary I of England [in 1558]. | ||||

| (7) | Description: Dagger/sickle/sword. Date: 23rd of August – 6th of September, 1526. Event(s): reference to what happened in ‘Rome, Florence, Genoa, Pavia, and other cities of Lombardia’ [which must be in reference to the Italian Wars of 1521 – 26]. | ||||

| (8) | Description: Guise of a star, ‘called del Sole [of the Sun], or hairs, or rays around it’. Date: 18th of January, 1538. Designation: C/1538 A1. Event(s): ‘Revolt in Florence against the great Cosimo di Medici’; arrival of King Francis I in Italy with a large army [in March and August 1536, the war ending with the Truce of Nice in 1538]; the encounter of the Pope with Emperor Charles 5, with King Francis I [probably in referral to the Truce meeting]; the war of the Turks against Venetians [Hayreddin Barbarossa's capture of Aegean and Ionian islands belonging to the Republic of Venice]; league of Christian princes against the Turks [Battle of Preveza; 28 Sep 1538]. | ||||

| (9) | Description: dart; called Acontie.Footnote106 Date: March, 1472. Designation: C/1471 Y1. Event(s): draught [in EnglandFootnote107]; ‘there were murdered Henry and his son Edward, King of England’ [which is unclear, for King Henry VI, who was possibly murdered in 1471, did not have a son as a successor called Edward, and the father of Edward V, who was possibly murdered in 1483, was Edward IV, not a Henry; Turks ‘ransacked nearly all of Hungary’ [Ottoman raid of Hungary's bridge in 1474; multiple attacks on Transylvania and Vojvodina during 1474–1475; Battle of Breadfield in 1479]. | ||||

| (10) | Description: small and without rays; in the guise of a sword; called Sifia; seen in Italy, France, and Germany. Date: 1st of August – mid-September, 1530. Event(s): ‘shortly thereafter came the wars of the Swiss’ [Second War of Kappel in 1531]; German peasants took to robbing [possibly referring to the German Peasants' War, which took place earlier, in 1524–25]. | ||||

| (11) | Description: shape of a horn; called Ceratia. | ||||

| (12) | Description: horsemane (crini di cavalli), called Ippeo. | ||||

| (13) | Description: of great splendour; in the west; in the sign of Capricorn. Date: 12th of November, 1577; visible for seven weeks. Designation: C/1577 V1 (Great Comet of 1577). Event(s): death of many kings, amongst whom that of Portugal in the reign of Fez [referring to King Sebastian (1554–1578)]; ‘death of his Highness in Flanders, where shortly beforehand there appeared many fires in the air’ [possibly in reference to Don Juan of Austria (d. 1578), who commanded the Army of Flanders and was sometimes referred to as ‘His Highness’Footnote108]. | ||||

The question one ought to ask is: what were Saliba's sources for both the dates and the descriptive details about these comets? Some of these events – in particular the so-called ‘great comets’ – are well documented in multiple sources on account of their great visibility. But what about the other mentioned examples? And were the astrological links to various crises his own?

It is only upon a very close inspection of Saliba's text that a revelatory piece of information comes to light: not only were all of these comets documented in a book published just five years prior by Italian astronomer Pietro Sordi, but significant portions of Saliba's text are actually reproduced directly from Sordi's work – in some places word for word. The publication in question is Discorso sopra le cometeFootnote109 (‘Discourse on comets’), printed by Seth Vioto in Parma in 1578 and dedicated to Barbara Sanseverino, the countess of Sala. Similarities between Saliba's and Sordi's works can also be noted in the very order in which the comet apparitions are presented (see ). Other than the comets of 1472 and 1530 (which Sordi presented in his Parte Prima but were displaced by Saliba) and that of 1512 (which Saliba moved to the beginning), the order followed by Saliba is the same as Sordi's (see the dark shaded cells in ) as found in the latter's Parte Seconda.

Table 1. A comparison of the order in which the comets are presented in Sordi's and Saliba's works.

But it is a close comparison of the two texts that provides the smoking gun that Sordi's work served as Saliba's source.Footnote110 Some examples (for there are others) are provided in , where highlighted text indicates very close – or outright exact – text matches in Sordi's and Saliba's works. It will also be readily apparent to the reader (particularly if they are able to understand Italian) that the similarity sometimes extends to the non-highlighted text as well. One may also note that Saliba sometimes omits some details that Sordi provided; no doubt, this must have partly been driven by necessity, as Saliba's space was limited.

The similarities extend to other phenomena and explanations, not just comets. By way of example, Saliba's (previously discussed) discussion of the appearance of an aperture in the sky (‘Apertura, ò fossa ò dir voliamo Voragine’) is also found in Sordi (‘aperture ouer fosse, ò voragini’, p. 25v). The same can be said of the appearance of a ‘mountain of fire’, and the armed horses, loud noises, and sound of trumpets in the sky (all described in Sordi, p. 25v). In pp. 26r-27r, Sordi explains at length painters' techniques employed to convey a sense of distance – be it close or far. In this vein, he also explains how a central dark cloud can give rise to the appearance of an ‘aperture’. The same explanations, albeit very much compressed, are found in Saliba.Footnote111 Ultimately, these explanations are derived from Aristotle, Meteorologica I.5.342b.14–21.

Table 2. Text comparison of Saliba vs. Sordi.

Referring to , the virtually identical text about the 1556 cometFootnote112 strongly suggests that Saliba relied entirely on Sordi's account of it, and that it is therefore unlikely that he observed (much less, was awed by) it himself, as one may initially speculate. We cannot, however, dismiss that the more recent comet of 1577 may have indeed motivated Saliba, for his text here departs from that of Sordi, who wrote:

Questa che vltimamente apparue, era di forma barbata, & quella propria che si chiama. Si vide in Parma il xiii. di Nouembre, del M.D.LXXVII. poco dapoi il tramontar' del Sole . . .

Comparing this to Saliba's description (quoted above, with the original in Italian provided in Note 87), we realize that the accounts here are quite different. Saliba may well have witnessed this comet. His remark that it was ‘of fresh memory’ may well suggest that he did so, and we should not forget Castagna's comments pertaining to Malta which we mentioned earlier. It is difficult to entertain the thought that someone as interested in the subject as Saliba would not have keenly observed such a remarkable comet. Therefore, one may surmise that the appearance of this comet together with Sordi's treatise a year later – a publication with which Saliba, it is amply clear, was quite intimate – provided the inspiration for Saliba to ascribe so much prominence to comets in his map. And to the map we shall now return.

5. Departure from or affirmation of the orthodox?

Besides the uncommon projection system that Saliba employed for it, in popular accounts, the map has sometimes been described to stand out in another respect, namely in that the sun and the moon are placed in the very same circle, occupying the same space as comets. This, it has occasionally been stated, signifies a departure from the Ptolemaic system. However, such a conclusion would be mistaken and rests upon a superficial reading of the map. The triple images of the sun and the moon depicted in the eighth zone are actually used to describe a meteorological phenomenon that manifests itself around either of the two bodies: the parhelion (plural parhelia) and parselene (plural parselenae), commonly referred to as sundog and moondog respectively. In the case of parhelia, ice crystals present in the atmosphere refract sunlight in such a way as to cause a halo (with a radius of 22 degrees) around the sun. Because of the appearance of a bright patch of light on either side of the sun, there seem to be three suns in the sky. In the case of the moon, refracted moonlight (by the very same mechanism) leads to the seeming appearance of three moons. Saliba explains the phenomenon as being due to the reverberation of light within a ‘rainy cloud’ lying close to the sun or moon, describing how the common people thought there were three suns or three moons.Footnote113 While Saliba's physical explanation is erroneous, his placement of this purely meteorological phenomenon amongst the regions of the air is correct. However, Saliba situating the optical phenomenon of lunar and solar halos amongst the regions of the air is not tantamount to him asserting that the sun and the moon themselves – their actual bodies – are located below the sphere of fire. In other words, one ought to distinguish between the optical phenomenon (whose cause is meteorological) and the bodies with which it is associated.Footnote114 (Moreover, recall Saliba's conventional ordering of the eleven heavens, amongst which there are those of the moon and the sun.) Conversely, Saliba's additional discussion of lunar and solar halos in the spandrels – outside the map itself – should not be interpreted to suggest that he treated these phenomena to be anything other than meteorological in nature. After all, as we have already seen, they were included in the map itself, i.e. they were treated as meteorological phenomena along with the others that are depicted therein, with Saliba's text leaving no doubt that he subscribed to contemporary views about them. So why did he also depict them in the spandrels? It is likely that the reason was a simple one: this otherwise empty space had to be filled with something, and the impressive phenomenon of the halo (along with eclipses, which are also discussed in the spandrels) was deemed important enough to merit additional commentary; these corner locations afforded Saliba the space to further explain their nature.

The planets and the stars are not depicted in Saliba's map,Footnote115 with the next (ninth) zone depicting the sphere of fire (within which we find a Phoenix and a Salamander depicted). Again, this should not be interpreted to mean that Saliba was departing from orthodox views, or that one need make a leap of imagination and consider the planets and the stars to be somehow located within the eighth zone (albeit not being depicted).Footnote116 Saliba is mostly interested in meteorological phenomena, and the planets and the stars do not fall under this category. Moreover, as we saw earlier, the introductory text itself leaves no doubt as to his commitment to the prevalent ideas of the time, adhering to the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic edifice.

The philosophy Saliba subscribes to comprises a geocentric system surrounded by the spheres of the various celestial bodies. The lack of inclusion of planets and stars in the map should not be interpreted to mean that there is a lack of agreement with traditional cosmology that follows Aristotle and Ptolemy. Saliba was well cognisant of and very much in agreement with this configuration; it is simply the case that the map is concerned with meteorology, and cometary phenomena were part of the domain of (Aristotelian) meteorology. Planets and stars occupy other, separate zones – superlunary zones – which are skipped by Saliba simply because they are not the subject of the map; they lie beyond the sphere of fire. In fact, it emerges quite clearly that a major focus of Saliba's is upon comets and their influence upon Earthly matters.

In respect to this, one may perhaps wonder whether the substantial astrological references would not have landed Saliba in hot water with the Catholic Church. Here, we should note two things. Firstly, the Church did not prohibit astrology through the Index of Prohibited Books so long as free will was maintained. Secondly, Saliba was careful enough to describe all such ‘visions’ as being messengers of God's wrath at sin,Footnote117 (which is not dissimilar to Kepler's view of comets carrying God's message,Footnote118 or Christoff Rothmann's argument framed as a question: ‘for who considering their portentous significance and most constant motion would impiously deny that God is the author?’Footnote119). Such a notion would fit within medieval, scholastic philosophy, built as it was upon Aristotle, who held that change (with respect to place) in the heavens was the cause of earthly perishing;Footnote120 it is not difficult to understand how the effects imparted by celestial bodies came to be viewed as being simply part of the thread of influence that extended all the way from the creator to the terrestrial.Footnote121 Finally, Sordi's own work, which carried the same assertions about comets' portentous nature as Saliba's later text, enjoyed the ‘licenza de Superiori’ after all,Footnote122 attesting that the Catholic Church did not have qualms with his interpretation.

Saliba's point about the heaven's east-to-west movement is also important to note, for it tells us that he did not ascribe diurnal motion to the Earth, meaning that he did not subscribe to a semi-Copernican system such as some of his contemporaries, e.g. the German astronomer David Origanus (1558–1628) who was amongst the first to admit that the Earth might rotate, or the English physician and natural philosopher William Gilbert (1544–1603).Footnote123 Such a system was unacceptable to the Catholic Church.

6. The map's reception and Saliba's other work

That Saliba's work was very well received is evidenced by the number of editionsFootnote124 that appeared followed the original publication. A Latin edition was published shortly afterwards by Belgian cartographer Cornelis de Jode, which was reissued by Paul de la Houve (c. 1600 or 1602). Further editions were produced by Ambrosius Schevenhuyse (a purchase of this version was recently made by the Maltese authorities), Jean Messager, Pierre Mariette the elder, Jean Boisseau (1638, and reissued by Louis Boissevin), and Gerald Jollain in 1681, a century after Saliba's original publication. A copy of Jollain's edition seems to have been held by Agius de Soldanis,Footnote125 who gifted it to Ignazio Saverio Mifsud (as recounted by the latter himselfFootnote126). Beyond the direct copies that followed, parallels can be drawn between the imagery of the Aristotelian regions of the air in Saliba's map and that in later works such as Robert Fludd's Catoptrvm Meteorographicvm of 1626.

What do we know about Saliba's other lost work that we mentioned earlier? It is said to have carried the titled Opera Meteorologica and was published in 1586, i.e. four years after the map.Footnote127 Fra Giuseppe Zammit (1646–1740), a Conventual chaplain, medical doctor, and the first professor of anatomy and surgery in Grandmaster Cotoner's Sacra Infermeria, also said it regarded meteorology's effects and influences (‘Meteorologicis effectibus, et influxibux’).Footnote128 Rev. Franceso Caruana Dingli wrote that Saliba was dear to Grandmaster Verdala, and that Saliba had gifted the latter a very masterly work that was eventually forwarded to the Vatican's librarian.Footnote129 However, past efforts to retrieve further information in this regard proved unfruitful.Footnote130

One may surmise, albeit this remains speculative, that this work may have been an expanded edition of the text that accompanied the 1582 map. If one trusts that it was indeed titled Opera Meteorologica (or, at the very least, dealt with such a topic) and accepts Abela's and Ignazio Saverio Mifsud's description, it is not unreasonable to assume that this was a further developed text on the same topic that Saliba emphasized so much in his map, namely meteorological phenomena and, particularly, cometary appearances. Unless this work ends up being discovered, however, this necessarily remains but only a conjecture.

7. Conclusion

When assessing Saliba's work, one necessarily has to confront two matters. One concerns the nature of Saliba's principal sphere of activity. The other matter concerns the question of where the novelty of his map lies.

In addressing the first matter, we may be tempted to query to what extent Saliba actually partook in astronomy, but it has to be borne in mind that in the sixteenth century there was no overt distinction between the domains of astrology, astronomy, and mathematics (and, by extension, the titles ascribed to their practitioner – astrologus, astronomus, and mathematicus).Footnote131 We may therefore carefully pose the question as: how much of what we nowadays consider to be astronomy did Saliba engage in? This can be looked at from two aspects: the descriptions that have been written about him, and the nature of his surviving work.

We have already seen Abela's heaps of praise for Saliba's ability in ‘astrology’. This is echoed by Fra Giuseppe Zammit, who praised Saliba's intelligence, and spoke of his uniqueness in astrology.Footnote132 He wrote that Saliba excelled in the liberal arts and philosophy, was a master of mathematics, and within these fields was to be regarded as a creator, not simply an alumnus. And in his strive for immortality, he wrote on meteorological effects and influences – work that was well regarded by erudite persons.Footnote133 While we cannot exclude that Zammit may have had access to some of Saliba's work, he himself notes that he was drawing from Abela, as is also amply evident from a comparison of the two texts. And speaking of similarity of texts, we may also observe that in places, Agius de Soldanis' description is practically identical to Zammit's.Footnote134 Francesco Caruana Dingli also wrote that Saliba was a master/teacher (‘maestro’) of mathematics of great ingenuity and experience, as well as being a famous astrologer.Footnote135

Therefore, we appreciate that the accounts that have been written of him (all of which seem to bear more than a passing resemblance to Abela's), invariably make mention of his abilities in astrology, mathematics, and meteorology. His knowledge of mathematics is reflected in the projection he used for his map. However, given the limitations of the extant accounts, and the afore-discussed interchangeability of terms, it quickly becomes clear that it is no use speculating about what these authors may have understood exactly by the term ‘astrology’, so we have to turn to Saliba's work itself.

A principal concern of the map is to provide an exposition of the celestial's influence upon the terrestrial – the scholastic question of influxu (in Saliba's case, this largely pertains to influxu cometarum as opposed to stellarum) – and what this entails for prognostication. Specifically, Saliba is especially interested in two branches of judiciary astrology: mundane/political and meteorological. The meteorology and description of cometary phenomena are Aristotelian, also exhibiting significant reliance on Pliny – and as far as this map is concerned, the text exhibits significant derivation from secondary sources, specifically Sordi's publication, which has been shown in this work to be a text which Saliba heavily borrowed from.

In terms of the astronomical system that is adopted, both the map itself and the accompanying text do not make any novel claims. It can also be said that the only strictly astronomical content – in the sense of pertaining to a model of the Universe – is found in the introduction in the form of a summary of the wholly orthodox Ptolemaic system, and the description of eclipses and haloes (and even the latter allude to weather omina).

As for the second question, while Saliba's mathematical ability in drawing up a map employing a polar azimuthal projection is certainly noteworthy, one must be careful in their appraisal not to risk entering the realm of hyperbole when it comes to other aspects of the map. Saliba's lifetime overlapped with that of Tycho Brahe, Galileo Galilei, and Johannes Kepler,Footnote136 but the latter two's contributions to astronomy would only come to the fore after the publication of Saliba's map. Given his manifest interest in comets, it is possible that he would have been aware of Brahe's arguments that they were superlunary. That being said, Brahe's 1578 report was intended for the Danish court,Footnote137 and was written in German; consequently, Brahe's views may not have been easily accessible to Saliba. In any case, judging by the text presented in Saliba's map, there is no indication that he subscribed to this view; not only is there no mention of it whatsoever, but in the sections Dell'aria and Dell'effetto che fà il sole, he conforms to a wholly Aristotelian cosmos in describing the ‘regioni’ extending to the moon (i.e. the sublunary sphere) where comets are explained to originate, again via a medieval/renaissance exposition of the Aristotelian framework.

We may therefore conclude that Saliba was very much a man of his time. His map presented a marvellously illustrated compilation of the prevailing ideas before the ‘new astronomy’ of Galileo and Kepler, carrying the name of Malta and Gozo afar via his proud declaration of being a ‘Maltese dal Gozo’. As far as the celestial aspects shown in the map are concerned, the content itself does not exhibit any divergence from the Ptolemaic and Aristotelian schemes, but the chosen method of presentation made for a very effective communication medium. Saliba fuses together Aristotelian concepts and religious ideas, in this respect continuing and promoting the scholastic tradition. The map is a pictorial summary of religious themes, ideas from classical antiquity, and the state of knowledge about the universe prior to the widespread adoption of Copernican theory, amounting to a special amalgamation of motifs. Through this elaborate visual representation – combining the underworld, earth, and heavens – the map would have captured the attention of his contemporaries, extending to a wider public.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the staff of the National Library of Malta, and the anonymous referees whose comments were of great help in improving this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Maurice Agius-Vadalà, ‘Antonino Saliba: L-Ewwel Xjenzat Malti’, in Oqsma tal-Kultura Maltija, ed. by T. Cortis (Malta: Ministeru ta' l-edukazzjoni u ta' l-intern, 1991), pp. 273–287.

2 In Ignazio Saverio Mifsud, Biblioteca Maltese dell'avvocato Mifsud: Parte Prima; che contiene l'Istoria Cronologica, e le notizie della perona, e delle opere degli scrittori nati in Malta, e Gozo fino all'anno 1650 (Malta: Palazzo, e Stamperia di S. A. S., 1764), p. 37: ‘Il Canonico Agius de Soldanis soprariferito ci ha comunicato la seguente notizia: (b) Il Saliba, nato al Gozo, non in Malta, fece altre compositioni, e nella loro soscrizione chiamasi dal Gozo di Malta.’ In a footnote (which is what the ‘(b)’ indicates) Mifsud explains that the information was conveyed in a personal letter: ‘In una lettera famigliare.’ Note that here and elsewhere in this article, archaic forms of the letter ‘s’ have been transcribed using the modern, standard form of the letter.

3 In Ibid.: ‘Bensi la Famiglia SALIBA, dalla quale noi abbiam l'origine di linea materna . . .’

4 Agius de Soldanis writes that he passed away a few years after 1583: ‘Poch'anni dopo mori in Alemagna’ (National Library of Malta [NLM], Ms. 145a, p. 391). But we have additional information from Rev. Francesco Caruana Dingli, who wrote a manuscript (also held at the National Library of Malta) titled

Galleria Maltese overo Brevissime notizia della vita di 2000 persone che onorarano Malta di loro patria, la memoria delle quali meritamente esige di non andare estinta presso i posteri. Scritta e compilata dal Sacerdote Francesco Caruana Dingli in Malta nell'anno 1846.

5 In Giovanni Francesco Abela, Della descrittione di Malta: Isola nel mare Siciliano con le sve antichita, ed altre notitie: Libr Quattro (Malta: Paolo Bonacota, 1647), p. 569, we read:

professore di varie scienze liberali, ne' quali era graduato; fù particolarmente famoso, e peritissimo nell'Astrologia, scrisse sopra le meteorologiche impressioni eccellemente; e diede alle stampe, con molta gloria del suo nome, essendo stata da lui dedicata l'opera al Sig. Gran Maestro Verdala suo benignissimo Principe.

6 The only known example of the original is at the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel, Germany.

7 In the bottom right corner, we read, ‘Marius Cartarius Incidebat Neapoli Anno 1582’. The number ‘2’ in the date appears faded. The date is also found mentioned in the main text in the section ‘Sette sono le età del mondo’, with Saliba writing ‘. . . adesso siamo nel An[n]o 1582’.

8 The original title spread over two lines reads:

NVOVA FIGVRA DI TVTTE LE COSE CHE SONO E DEL CONTINVO SI GENERANO DENTRO LA TERRA E SOPRA NELLAERE COMPOSTA PER IL MAGNIFICO ANTONINO / SALIBA MALTESE DAL GOZO DOTTORE IN FILOSOFIA TEOLOGIA ET IN LEGGE CANONICA E CIVILE A BENEFITIO VNIVEALE DICOLORO CHE DESIDERANO SAPERE LI OCCOLTI SEGRETI DELLA NATVRA COLLA SVA DICHIArati[o]ne.

9 In the context of the title and work, dichiaratione (declaration) can be understood and translated as ‘explanation’.

10 This is said in a passage where Saliba expresses his disagreement with the notion that those who eat something that has been struck by lightning either die quickly or become mad: ‘. . . ma in q[u]esto io li son contra. poi ch[e] essendo io comessario delle Decime p[er] Malta nostra patria nel [15]·72· in Calauria et in Abruzzo ho ma[n]giato piu volte carne di Animali fulminati’. Note that Calauria is a Greek island; it is probable that this was really intended to read Calabria.

11 In NLM, Ms. 1142, fol. 193r: ‘Fu spedito Ambasciatore a S. M. il Re di Francia, e poi al Re di Sicilia, decorato col grado di Cavaliere d onore e Capo della Militia’.

12 ‘Sancti Patrii’.

13 M. Agius-Vadalà, op. cit. treats it from the cartographic angle; Frank Ventura, L-Astronomija f'Malta (Malta: Pubblikazzjonijiet Indipendenza, 2002) takes a brief look at some of the astronomical and astrological aspects.

14 A brief description and limited information is provided in Rodney W. Shirley, The Mapping of the World: Early Printed World Maps: 1472–1700 (London: New Holland (Publishers) Ltd, 1993), p. 169; Peter Whitfield, The Image of the World: 20 Centuries of World Maps (London: The British Library, 1994), p. 70; and Denis E. Cosgrove, ‘Images of Renaissance cosmography, 1450–1650’, in History of Cartography, Vol: 3, ed. by David Woodward (Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 2007), pp. 55–98. (In the case of the latter, the information is limited to a caption to ‘Colour Plate 1’ and a mention in two sentences in pp. 85–87.)

15 See Christopher D. Johnson, ‘Encyclopedia and Encylopedism’, in Encyclopedia of Renaissance Philosophy, ed. by M. Sgarbi (Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2022), p. 1104.

16 As expressed in the title, ‘tvtte le cose che sono e del continvo si generano dentro la terra e sopra nell aere’.

17 For example, we find it used in Sheet 13 of Mercator's 1569 map, and a 1581 map by Guillaume Postel (1510–1581). For the latter, see, e.g., R. W. Shirley, op. cit., entry 144. After Saliba, we find it used in the 1587 planisphere of contemporary Italian cartographer Urbano Monti (1544–1613) and a 1593 map by Cornelis de Jode depicting a hemisphere from the equator to the arctic pole, descriptively titled ‘Hemispheri ab æquinoctiali linea, ad circvl

poli arctici’.

18 For example, near the equator, Saliba depicts Burnei and the Amazon, and shows locations as high in latitude as the Tartar mountains (49 degrees) and Labrador (53 degrees). On the cartographic aspect, the reader is also referred to R. W. Shirley, op. cit. An article published in Maltese, partly based on the second edition (1987) of Shirley's work, is that of M. Agius-Vadalà, op. cit.

19 ‘Questa Machina del Mondo co[n]tiene in se tutte le cose ch[e] Idio creo p[er] gloria sua.’ Note that a tilde was used to denote abbreviations, e.g. cõ=con, nõ=non, lle=quelle. Where in such instances I have spelled out the whole word, I have indicated my edit by the use of square brackets.

20 ‘. . . moles et machina mundi’ in Lucretius, De Rerum Natura V.96.

21 See, e.g. Edward Grant, The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional, and Intellectual Contexts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 21.

22 De revolutionibus orbium coelestium carries a preface addressed to Pope Paul III, in which Copernicus complains about the uncertainty regarding the motion of the ‘world machine’, which was created for our own sake by the best artisan, even as philosophers examined trivialities with such great precision:

Hancigitur incertitudinem Mathematicarum traditionum, de colligendis motibus sphærarum orbis, cum diu mecum reuoluerem, cœpit me tædere, quòd nulla certior ratio motuum machina mundi, qui propter nos, ab optimo & regulariss omnium opifice, conditus esset, philosophis constaret, qui alioqui rerum minutiss, respectu eius orbis, tam exquisite scrutarentur.

23 On the properties of the elements in regard to weight and lightness, see Aristotle, De caelo IV.4.311a.15–312a.21.

24 ‘. . . e p[er] questa lor trasmutatio[n]e, e moti de’ Celi, si ma[n]tiene nello esser' suo, questa gra[nde] Machina del Mo[n]do . . .'

25

. . . tutti sono mobili fuor ch[e] la Terra, la q[ua]le ristretta in sè stessa, è posta nel piu basso luogo, a guisa d'una polla rito[n]da, et è ce[n]tro della circo[n]fere[n]tia del Cielo, ch[e] s'aggira in torno, et essa stà im[m]obile ferma et è quasi u[n] punto rispetto al Cielo tutto.

26 ‘. . . è detta dà i filosofi Quinta essenza . . .’

27 ‘. . . dall'Orie[n]te all'Occide[n]te, ritorna[n]do all Oriente, e finiscie il moto suo in 24 hore’.

28 ‘Viè poi il moto de’ Pianeti dall' Occide[n]te all'Orie[n]te sop[r]a i poli del Zodiaco . . .' In Agius-Vadalà, op. cit., p. 275, both this movement and the sky's east-to-west motion were incorrectly ascribed to the Earth.

29 ‘. . . in sè co[n]tiene xi·Cieli; cioè la Luna, Merc[uri]o, Vener[e,] Sole, Marte, Gioue, Saturno, il Cielo stellato, detto firmame[n]to, il Ciel Cristallino[,] il p[rim]o Mobile, et il Ciel’ Empireo . . .'

30 Petrus Apianus, Cosmographicus liber Petri Apiani mathematici studiose collectus (impensis P. Apiani, 1524), p. 6.

31 ‘q[ue]sti Cieli no[n] sono ne Eleme[n]ti, nè di Elem[e]nti co[m]posti, nè gravi nè leggieri, no[n] caldi, nè fredi [sic], e finalme[n]te di ogni Elem[e]ntare impressione liberi, mà tutti sono lucidi, traspare[n]ti, e di bei lumi, e stelle ornati.’

32 ‘Universalis autem mundi machina in duo dividitur: in etheream et elementarem regionem.’ For the latin text of Tractatus de sphaera, see Lynn Thorndike, The Sphere of Sacrobosco and Its Commentators (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1949).

33 ‘Et hec a philosophis quinta essentia nuncupatur . . .’

34 For a short, introductory review, I point the reader to Craig Martin, ‘Meteorology in Renaissance Science’, in Encylopedia of Renaissance Philosophy, ed. by M. Sgarbi, pp. 2178–2185.

35 See, e.g. Craig Martin, ‘Interpretation and Utility: The Renaissance Commentary Tradition on Aristotle's Meteorologica IV’ (doctoral thesis, Harvard University, 2002); and Craig Martin, Renaissance Meteorology: Pomponazzi to Descartes (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2011). On Aristotelian meteorology following the Lutheran reformation, see Rienk Vermij, ‘A Science of Signs. Aristotelian Meteorology in Reformation Germany’, Early Science and Medicine, 15 (2010), 648–674.

36 The full title of the work reads: Francisci Vicomercati Mediolanensis in qvatvor libros Aristotelis Meteorologicorvm commentarij. Et eorvndem librorum e Græco in Latinvm per evndem conversio. Ad Carolvm a Lotharingia Cardinalem. Lvtetiae Parisiorvm, apvd Vascosanvm. For a bio-bibliography on Vimercato, see Neal W. Gilbert, ‘Francesco Vimercato of Milan: A Bio-Bibliography’, Studies in the Renaissance, 12 (1965), 188–217.

37 On Pomponazzi, see, e.g. Craig Martin, Renaissance Meteorology: Pomponazzi to Descartes.

38 Lectiones, in quartum Meteororum Aristotelis librum (Venetijs: apud Franciscum de Franciscis Senensem, 1563); Lectiones super primum librum meteorologicorum Aristotelis, nunc recens in lucem editae (Venetiis: ex officina Ioan. Baptistae Somaschi, 1565); Lectiones, in secundum, ac tertium meteororum Aristotelis libros (Venetiis: apud Hieronymum Scotum, 1570).

39 See Donato Verardi, ‘I Meteori di Cesare Rao e l'aristotelismo in volgare nel Rinascimento’, Rinascimento meridonale, 3 (2012), 115–128.

40 This was not limited to Aristotle's meteorology; see, e.g. Luca Bianchi, Simon Gilson, Jill Kraye (ed.), Vernacular Aristotelianism in Italy from the fourteenth to the seventeenth century (London: The Warburg Institute, 2016). On meteorology specifically, see Ivano Dal Prete, ‘Vernacular meteorology and the antiquity of the earth in medieval and renaissance Italy’ in ibid., pp. 139–159. The vernacularisation of Aristotle did not proceed only in Italian. A thirteenth century example in French is Mahieu Le Vilain's Livre des Météores; see Joëlle Ducos, La météorologie en Français au Moyen Âge (XIIIe-XIVe siècles) (Paris: Honoré Champion, 1998).

41 For a critical edition, see Rita Librandi, La ‘Metaura’ d'Aristotile: volgarizzamento fiorentino anonimo del XIV secolo. Edizione critica (Naples: Liguori, 1995).

42 See Eva Del Soldato, ‘“The Best Works of Aristotle”: Antonio Brucioli as a Translator of Natural Philosophy’, in Vernacular Aristotelianism in Italy from the Fourteenth to the Seventeenth Century, ed. by L. Bianchi, S. Gilson, and J. Kraye, pp. 123–138.

43 See Simon Gilson, ‘Vernacularizing Meteorology: Benedetto Varchi's Comento sopra il primo libro delle Meteore d'Aristotile’, in ibid., pp. 161–181.

44 See Dario Tessicini, ‘Fausto da Longiano's Meteorologia (1542) and the vernacular transformations of Aristotle's natural philosophy in the sixteenth century’ in Rivista di Storia della Filosofia, 2 (2019), pp. 309–326.

45 Some section titles in da Longiano's work, which immediately convey the similarity with topics covered by Saliba, are: De la divisione de l'aere; L'aere ricettacolo de li dvi fvmi hvmidi e secchi; De li vapori et essa lationi; De gli effetti del sole in terra; De la rvgiada; De la brina; De la manna; De la nebbia e nvgole; De le rane generate ne l'aria; De la piogga; De le fiamme nottvrne; De le stelle credvte cadere dal cielo; De le apertvre del cielo; De tvoni, lampi, fvlgvri, fvlmini, incendii; Del tvono; Dei lampi; Del fvlgvre e del fvlmine; De la cometa; Che significhi la cometa.

46 ‘L'Aria è corpo ch[e] rienpie ogni luogo, e seco[n]do Arist[otile] si divide in tre parti, ò Reggioni . . .’

47 ‘la terza Reggione cominicia dalla somità di detti Monti in sù verso la Luna, e di altri simili fin al co[n]cavo del fuoco.’ From the context, the phrase ‘altri simili’ ‘others similar’ would seem to be in reference to mountains similar to those mentioned.

48 Meteorologica I.4.341b.5–24.

49 Properly rugiada. Elsewhere, Saliba writes ‘ruggiada’.

50

come si vede nella ·3a· Reggione dell'aria ove si generano et iui s'im[m]fiamano dette essallationi p[er] lo moto della Sfera del fuoco, e dei corpi Celesti e seco[n]do la varia dispositione e quantità della essalatione, ò piu, ò meno accesa, si mostra nell'aera in tante diverse imagini, e forme di corpi ig[n]ei . . .

51 ‘E sè l'essalatione sarà poca e rara, ch[e] non possa salire in sù . . .’

52 ‘. . . varie e diversse fiam[m]ette e se[n]tille di fuoco et alle volte a guisa di ca[n]delucce accese . . .’

53 Their illustration is found in Zone 8.