ABSTRACT

According to some economists, central banks should use ‘helicopter money’ to boost inflation (expectations). Based on a survey among Dutch households, we examine whether respondents would spend the money received via such a transfer. Our results show that respondents expect to spend about 30% of the transfer and that helicopter money would hardly affect inflation expectations. Furthermore, whether transfers come from the central bank or the government makes no difference. Finally, our results suggest that the effect of helicopter money on public trust in the ECB is ambiguous.

I. Introduction

At the end of 2014, inflation in the euro area dropped below zero and thereafter inflation remained persistently low for several years and well below the European Central Bank’s (ECB) aim of price stability (i.e. an inflation rate in the medium term of below but close to 2%). At the same time, market-based long-term inflation expectations became less well anchored and started drifting away from this target (see de Haan et al. Citation2016 for a discussion).

In January 2015, the Governing Council of the European Central Bank, therefore, decided to launch the expanded asset purchase program (EAPP), better known as quantitative easing (QE). Several observers have expressed doubts that the ECB’s QE will achieve the desired sustained adjustment of inflation (expectations) in line with the ECB’s aim for price stability (see Blinder et al. Citation2017 for a discussion). Some economists have therefore suggested the ECB to use ‘helicopter money’, i.e. the monetary financing of government expenditure or transfers to households.Footnote1 According to Borio, Disyatat, and Zabai (Citation2016), ‘helicopter money is best regarded as an increase in economic agents’ nominal purchasing power in the form of a permanent addition to their money balances.’

In a hearing in the European Parliament, ECB President Draghi said: “It’s a very interesting concept that is now being discussed by academic economists and in various environments. …. but of course by this term “helicopter money” one may mean many different things, and so we have to see that.” The purpose of our article is to examine whether one form of helicopter money (i.e. a transfer to households) would affect private spending and raise inflation expectations.

Most proponents of helicopter money are not very specific about how helicopter money can be created. An exception is Muellbauer (Citation2014), who suggests providing ‘all workers and pensioners with social-security numbers (or the local equivalent) with a payment from the ECB’. In his view, it is to be preferred that the ECB is responsible instead of the government: ‘There is an important difference between the ECB implementing a €500 per-adult-citizen hand-out as part of monetary policy and governments doing this as traditional fiscal policy. Economists have long worried about myopic politicians over-spending, for example, just before an election in order to influence the voters and thus creating a “political” business cycle, or simply perpetually spending too much, and as a result running too high government deficits. … But it is quite a different matter for an independent central bank … to directly hand out cash to households as part of its method of meeting its inflation mandate.’ We take this specific proposal for helicopter money as the starting point for our research.

A crucial question is whether such a central bank financed transfer would, in fact, lead to higher consumer spending and therefore – via its effects on aggregate demand – to higher inflation (expectations). We examine this issue by asking a panel of Dutch households whether they intend to spend the money received. To analyse whether the amount of the transfer matters, we ask this question for two amounts, namely €500 and €2000. In addition, we test whether it makes a difference whether the money would be distributed by the ECB or national governments as suggested by Muellbauer (Citation2014).

The announcement of helicopter money may also have a direct effect on inflation expectations. For instance, when individuals expect that the majority of households would spend the money transfers, these individuals may raise their inflation expectations accordingly, even when they do not intend to spend their helicopter money themselves. As a result, even when only a small part of money transfers is actually spent, helicopter money could be effective in raising inflation expectations among the public. Similarly, it may affect inflation expectations via a signalling effect, i.e. the use of helicopter money emphasises the commitment of monetary authorities to their inflation target. We therefore also examine whether a transfer to households would affect their inflation expectations.

A related question is how helicopter transfers, which would be a new monetary policy instrument, would impact public trust in the ECB. Public trust in the ECB is important because central banks ‘ultimately derive their democratic legitimacy from the public’s trust in them’ (Ehrmann, Soudan, and Stracca Citation2013). Moreover, high public trust contributes to an effective functioning of the ECB, for instance, by contributing to the credibility of communication (Blinder et al. Citation2008) or to anchoring the public’s inflation expectations (Christelis et al. Citation2016). We therefore also examine how helicopter money affects trust in the ECB.

Our results show that respondents expect to spend about 30% of a helicopter transfer instead of using the full amount to increase spending. Whether the transfers come from the ECB or the government makes no difference. Furthermore, helicopter money would hardly affect inflation expectations. Finally, our results suggest that using helicopter money would have mixed consequences for public trust in the ECB.

Two recent papers that were independently written at about the same time as our study deal with similar issues. Djuric and Neugart (Citation2016) fielded questions in a survey which constitutes a representative sample of the German population. They randomly divided participants into four sub-groups which were confronted with distinct versions of unconventional monetary and fiscal policy scenarios. These authors report that on average subjects indicated that they would spend 451 Euros when the central bank makes a one-time helicopter money drop of 1200 euros. They do not examine whether helicopter money would affect trust in the ECB. Similar to our findings, the authors report that it hardly matters whether the central bank would print the money and transfer it directly to the households or whether the Treasury would borrow the money from the central bank and transfer it to the households.

A recent study by ING comes to similar conclusions as the present study (Bright and Janssen Citation2017). Almost 12,000 people in 12 countries across Europe (including the UK) were asked how they would spend €2400 (which they would not have to repay); the study reports that only 26% of the respondents say they would spend most of the money. For the Netherlands, the authors report that 29% of the respondents answer that they would spend most of the money received. According to our results, respondents expect to spend about 30% of the transfer. Also, the ING study does not examine whether the amount received matters and whether helicopter money would affect trust in the ECB; the study also does not provide an empirical model to explain respondents’ replies. Furthermore, we have some doubts about the setup of this research. The most important question asked is: “Imagine you received €200 in your bank account each month, for a year. You are free to do what you want with the money and don’t need to repay it or pay taxes on it. How would you use this extra money?” The possible answers provided include: ‘save or invest most of it’ and ‘spend most of it’. These answers are very imprecise, which may seriously affect the outcomes. In our survey people are asked to distribute the amount received over various categories which provides a more accurate view about how helicopter money would be spent.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 compares the impact of QE and helicopter money on the real economy; it also reviews evidence that may be relevant in assessing whether helicopter money would work. Section 3 outlines the survey and Section 4 presents and discusses the outcomes of our survey. Section 5 concludes.

II. QE versus helicopter money

There is a major difference between QE and transfers financed by the central bank. The transmission of QE to the real economy is indirect, i.e. it runs via financial markets and institutions. In contrast, transfers into people’s accounts would directly influence private sector agents’ spending capacity rather than hoping for a trickle-down effect from financial markets and institutions. Furthermore, it would be targeted to people having a higher marginal propensity to spend than the wealthy owning the assets whose prices are boosted by QE (Muellbauer Citation2014).

Although most evidence, which mostly refers to the US, suggests that financial markets were affected in the intended direction by central banks’ asset purchase programs (see Blinder et al. Citation2017; de Haan and Sturm Citation2019 for discussion of the evidence), this does not necessarily imply that these unconventional policies have been able to increase inflation or inflation expectations. Indeed, several Fed policymakers, have noted that the transmission channels of QE to the real economy are not well understood and that estimates are subject to substantial uncertainty (cf. Rosengren Citation2015; Williams Citation2014).

And even if QE may have ‘worked’ for the US, some arguments have been raised why this may be less obvious for the euro area. For instance, the impact of asset purchase programs may differ depending on economic settings, such as the steepness of the yield curve at the time when the program is announced (Blinder et al. Citation2017). Note that when the ECB decided to introduce QE, the yield curve was already fairly flat due to previous ECB unconventional policies.

In a speech in November 2002, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke (Citation2002), suggested helicopter money as one means to boost the economy. Proponents of helicopter money argue that if a central bank wants to raise inflation and output in an economy that is running substantially below potential, one of the most effective tools would be simply to give everyone direct money transfers. In theory, people would see this as a permanent one-off expansion of the amount of money in circulation and would spend it, thereby increasing economic activity and helping to push inflation back up to the central bank’s target.

According to Buiter (Citation2014), a helicopter drop of money is a permanent and irreversible increase in the nominal stock of fiat base money in contrast to QE. However, a helicopter drop may imply that central banks’ dividends paid to the government would be reduced or that the government would have to transfer money to the central bank to cover episodes of negative net income (Reis Citation2015). Under those circumstances, helicopter-money-financed transfers may not be as permanent as suggested by its proponents. And to the extent that consumers are Ricardian, the transfer may then not lead to higher private consumption. Furthermore, as households are currently highly leveraged in several countries in the euro area, they might decide to use the money received to improve their net asset position.

Proponents of helicopter money argue that it would boost demand even if existing government debt is already high and/or interest rates are zero or negative (Buiter Citation2014; Gali Citation2014). Bernanke (Citation2016) identifies four channels through which helicopter money would stimulate demand: 1. the direct effects of the public works spending on GDP, jobs, and income in case government spending is financed by money creation; 2. the increase in household income, which should induce greater consumer spending in case helicopter money takes the form of a transfer to households; 3. a temporary increase in expected inflation due to the increase in the money supply, which in turn should incentivise spending; and 4. unlike debt-financed fiscal programs, a money-financed program does not increase future tax burdens and so should provide a greater impetus to household spending than expansionary fiscal policy financed by government debt. However, the extent to which these effects materialise is an empirical question.

Would helicopter money in the form of transfers to households work?Footnote2 Due to lack of prior use of the policy instrument, proponents often refer to related experiences with tax rebates in the US, Australia and Singapore.

Johnson, Parker, and Souleles (Citation2006) report that between 20 and 40% of the 2001 US rebate was spent in the quarter in which the cash was received – and about another third in the quarter afterwards. In their study of the 2008 US rebate Parker et al. (Citation2013) conclude that households spent 12–30% (depending on the specification) of their payments on nondurable goods during the 3-month in which payments were received, and a significant amount more on durable goods, primarily vehicles, bringing the total response to 50–90% of the payments. Similarly, in an analysis of the 2008 US rebate using AC Nielsen Homescan data, Broda and Parker (Citation2008) find a first-quarter marginal propensity to consume of about 0.6 and a two-quarter marginal propensity to consume of about 1.

In his study of the Australian 2008/09 tax rebate, called a ‘bonus’, Leigh (Citation2012) reports that 40% of households who said that they received a payment reported having spent it, while 24% indicated they had saved the money and almost 36% used it to pay off debt.

Agarwal and Qian (Citation2014) find an average marginal propensity to spend of 0.8 within 10 months of the announcement of an unanticipated one-time cash pay-out which ranged from $78 to $702 per person in Singapore. This fiscal stimulus of $ 1.17 billion amounted to 0.5% of Singapore’s annual GDP in 2011, and was equivalent to 12% of Singapore’s monthly aggregate household consumption expenditure in 2011. The authors also find that consumption rose primarily in small durable goods, while consumers with low liquid assets or with low credit card limit showed stronger consumption responses. They also report a strong announcement effect: 19% of the response occurs during the first two-month announcement period.

There is also a related literature on how people spend money won in a lottery. A good example is the study by Fagereng, Holm, and Natvik (Citation2016), who report a 6-month average marginal propensity to spend from lottery wins of 0.35 for the population of Norway. They also find variation across the amount won (the marginal propensity to spend among the 25% winning least is twice as high as among the 25% winning most) and the amount of liquid assets that price winners have. Even more related to our work is the study by Kuhn et al. (Citation2011) who study the effects of lottery prices on spending in the Netherlands. These authors do not detect any effect of winning a prize (€12,500 per lottery ticket) on most components of winning households’ expenditures, except for spending on cars and other durables.

As Muellbauer (Citation2014) points out, most evidence discussed above contradicts simple textbook versions of the permanent income hypothesis of consumption. Referring to some of his previous work (Aron et al. Citation2012; Chauvin and Muellbauer Citation2013), he concludes that ‘between 40 and 60% of a surprise transfer of €500 would be spent fairly quickly.’ He also argues that this percentage would depend on the net asset position of households. For instance, liquidity constrained households tend to have higher propensities to consume in response to income shocks (Jappelli and Pistaferri Citation2010, Citation2014; Kaplan and Violante Citation2014). This would suggest that the spending impact would be less in Germany, where many households already have a lot in their saving accounts, but in Spain, Portugal, and Greece, where many households are perhaps more liquidity-constrained, the effects would be large.Footnote3 Note however that Muellbauer’s estimates of quick and substantial spending out of surprise transfers are not unchallenged. For instance, recent research by Fuster, Kaplan, and Zafar (Citation2018) finds for the US a mean marginal propensity to spend out of a $500 transfer within three months of 8%. In their survey, three-quarters of respondents do not intend to change spending at all after a one-time $500 payment and some indicate they would reduce spending.

III. The survey

To investigate the willingness of consumers to spend helicopter money and whether helicopter money affects inflation expectations and trust in the ECB, we have designed a survey. This survey has been fielded among the members of the CentERpanel. The CentERpanel is an internet panel run by CentERdata, a survey research institute affiliated with Tilburg University. The composition of the panel is representative of the Dutch-speaking population. Recruitment is based on a random national sample. The initial selection interview takes place via traditional communication channels (mail, telephone or house visits). Once participants confirm their willingness to participate in the panel, they are explained that the surveys are done via the internet and that participants without internet access are granted access by CentERdata. The careful selection procedure makes sure that also the part of the population that is not yet connected to the Internet is represented in the panel (see Teppa and Vis Citation2012). As there is no intervention of an interviewer, respondents can answer questions at their own pace and convenience.

Annually, panel members complete six survey modules on work, income, health, assets and debt, and economic and psychological savings concepts. This longitudinal dataset, known as the DNB Household Survey (DHS), provides a rich set of background information on panel members. In addition to the annual surveys, participants in the CentERpanel regularly complete ad hoc surveys on a variety of topics designed by researchers for specific research projects. Data collected via the CentERpanel have been used in several studies such as Christelis et al. (Citation2018), Van Ooijen and van Rooij (Citation2016), Van der Cruijsen, Jansen, and de Haan (Citation2015), and Van Rooij et al. (Citation2011, Citation2012).

From 13 until 24 May 2016, our questionnaire was offered to all panel members aged 18 and older. Compared to traditional surveys conducted by telephone or mail, the response rate to surveys in this Internet household panel is usually quite high. In our case, 2223 out of 2848 respondents completed the survey which gives a response rate of 78.1%.

We merge the data from our survey with information from the 2015 DHS modules. This enables a more extensive analysis of the survey data, but note that the number of observations for these additional variables is about 400 less than for our survey because there is not a one-to-one correspondence between participants in the surveys. Specifically, we include information on the level and composition of household wealth. Net household wealth is measured as the net value of financial and real assets and debts. The measurement of wealth follows a bottom-up approach, where households first report whether they own several assets or debt items and if so they are asked to report the asset and debt values item by item (see Alessie, Hochguertel, and van Soest (Citation2002) for a detailed description of the construction of household wealth using the DHS modules.) Before filling in the asset and debt module, respondents are kindly requested to gather financial records and income tax files so that they can easily access the relevant financial information. For the value of the house, which represents a large proportion of wealth for many households, respondents typically have to come up with their own estimate. While these subjective self-reports may contain measurement error, it is self-estimated wealth that most likely affects spending decisions (as pointed out by Christelis, Georgarakos, and Jappelli Citation2015). Note that collective pension savings are not included in the measure of household wealth because respondents do not have an individual claim on the collective pension investments of their pension fund. However, to take into account that many workers compulsory save in collective company pension plans (as to supplement the pay-as-you-go state pension benefits), we include a dummy for pension fund membership in the empirical analysis.

provides information on the respondents’ gender, age, education, gross monthly income, wealth, education level, whether they are living with a partner, their social status, and where they live. The average respondent turns out to be male, in his early 50s, and living with a partner. Compared to the Dutch population our sample of respondents is more educated on average. Correspondingly, respondents with high income and high wealth are somewhat overrepresented. For instance, 44% of the respondents have a gross personal income in the highest tertile of the population-wide distribution. Therefore, we use non-response weights throughout the article in order to present findings that are representative of the Dutch population in terms of gender, age, education, and income.

Table 1. Sample statistics.

Appendix 1 lists our main survey questions and explains the survey structure. The first questions ask what respondents would do if they were to receive a transfer (either €500 or €2000) from the ECB or the national government. The options given are: donate the money, spend it, save it, invest it, use it for down payments on debt (such as mortgages) or use it for another purpose. Respondents were asked to allocate the money received over these categories. They also could choose ‘I do not know’. Similar to Jappelli and Pistaferri (Citation2014), we do not specify the horizon in our survey questions. Subsequent analysis shows that adding a 12 months horizon to the question does not affect our main findings (results available on request).

The survey also contained several questions pertaining to respondents’ knowledge. For instance, we asked whether respondents are aware of QE, heard about the concept of helicopter money, know the name of the ECB President, and can identify the main objective of the ECB. This allows us to test whether respondents’ knowledge is related to their answers on how they intend to allocate the money received. In the questionnaire, we stressed that there was no need to search for the correct answers (see Appendix 1). We explicitly mentioned that participants should not worry about giving an incorrect answer. By including these comments, we wanted to minimise the likelihood that people would use internet sources (such as the ECB website) to search for information while completing the survey. Of course, we cannot exclude that people searched for correct answers. Still, searching for the answers to these questions would have taken quite some time. Also, we did not offer participants any monetary incentives for answering questions correctly and survey responses are anonymous so that it is not possible for researchers to link the number of correct answers or other personal information to individuals. Therefore, it seems unlikely that a significant portion of the respondents engaged in searching behaviour.

IV. Results

Would respondents spend the money received?

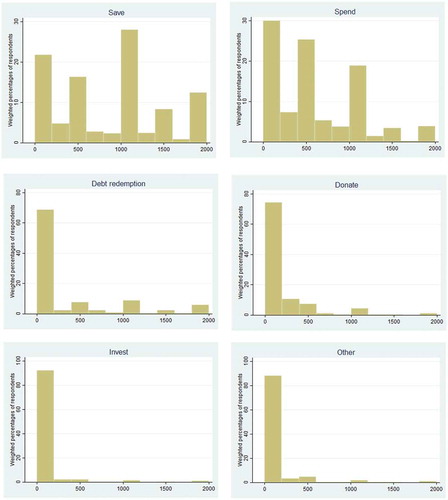

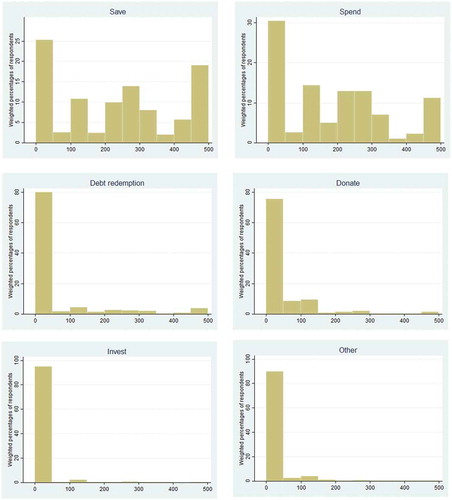

and show the distribution of the answers to the questions about how the respondents would allocate a helicopter money transfer (averages as well as percentiles of the distribution). We draw four conclusions from these results. First, the largest part of the money received would be saved (i.e. put on a saving account or used for debt redemption). For instance, out of a money transfer of €500 by the ECB, on average €220 would be saved and €50 would be used for debt redemption.

Table 2. Allocation of helicopter transfer.(Weighted average allocation in euros; percentages of total amount in parentheses)

Table 3. Allocation of helicopter transfer.(Percentiles of weighted allocation distribution in euros)

Second, the share of the transfers received that would be spent on average drops from about 34 to 28% if the size of the transfer increases from €500 to €2000. Thus, the marginal effectiveness of a money transfer in terms of money spent decreases with the size of the transfer.Footnote4 In fact, respondents state that they intend to use a larger part of the money transfer for other purposes such as redeeming debt and – to a lesser extent – for donations or investments.

Third, as shown in , these averages mask a large heterogeneity in individual responses. This figure shows the distribution of responses to a €2000 transfer from the ECB in a histogram with 10 equally sized bins of €200. For instance, over 20% of respondents save (almost) nothing and over 10% of respondents save (almost) the full money transfer. Focusing on the smaller €500 money transfer (instead of €2000), we find comparable levels of heterogeneity across individuals’ marginal propensities to spend as shown in .

Finally, it does not make any difference whether respondents would receive the transfer from the ECB or the national government. As shown in , differences in the average allocations are economically small and statistically insignificant. The latter finding, therefore, does not support Muellbauer’s (Citation2014) view that a helicopter money transfer via the central bank would be more effective than a helicopter money transfer via the government.

Do knowledge, income and wealth matter?

The way consumers respond to a helicopter money transfer may depend on their knowledge of the current economic situation and the ECB or on their personal financial situation. In fact, evidence suggests that economic and financial knowledge is an important determinant of many economic decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell Citation2014). For example, studies have documented a relation between knowledge and the decision to enter stock markets (Van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie Citation2011), the accumulation of wealth (Van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie Citation2012), the choice of saving accounts (Deuflhard, Georgarakos, and Inderst Citation2019), the choice of mortgage products (Van Ooijen and van Rooij Citation2016), and inflation expectations (Van der Cruijsen, Jansen, and de Haan Citation2015).

To investigate the relation between helicopter transfers and knowledge, we have asked several questions about respondents’ knowledge. See Appendix 1 for the precise wording of the questions. First, we explained the term helicopter money and asked whether respondents had heard about helicopter money before. We have done this because asking these questions without explaining the concepts makes answers received to these questions possibly unreliable, as people may not really know what QE and helicopter money are and still claim that they heard about it. However, a drawback of this approach is that it may be easier to recall hearing about something (or believing that one has) when first being told about it. Nevertheless, few respondents report having heard about these concepts. It turns out this was only the case for 9% of the respondents. It also turns out that the percentage of the respondents who are aware of QE is only slightly higher (12%). This low awareness is consistent with the fact that the communication strategy of central banks is primarily aimed at financial markets (Blinder et al. Citation2008). It is also consistent with the way laymen appear to acquire and process information (Hayo and Neuenkirch Citation2018).

In addition, we asked about the name of the president of the ECB and the responsibilities of the ECB. Almost 35% knows that Mario Draghi is the President of the ECB. Furthermore, we asked about the tasks and objectives of the ECB. The results show that two-thirds of the respondents are aware that the ECB is responsible for banking supervision. It turns out that 41% of the respondents know that price stability is among the monetary policy objectives of the ECB, but only 26.4% correctly indicated that this is the ECB’s main objective. These results are broadly in line with the findings of Van der Cruijsen, Jansen, and de Haan (Citation2015).

shows the relationship between respondents’ knowledge and how they spend a €2000 transfer by the ECB.Footnote5 Knowledge is measured using respondents’ answers to the questions outlined above. We use respondents’ estimates of the current rate of inflation to proxy their knowledge of the current economic situation. The median respondent estimates current inflation in the Netherlands at 1.2% which, at the time, was −0.2%, while 3% of the respondents estimate current inflation to be negative (both within the group of the 55% of the respondents who answered this question). We consider respondents whose estimate is reasonably close – i.e. within a range of plus or minus 1 percentage point from the actual inflation rate – to have knowledge about current inflation.

Table 4. The impact of knowledge on allocation of €2000 transfer from ECB.(Weighted average allocation in euros; percentages of total amount in parentheses)

Our results do not provide strong evidence that knowledgeable respondents would spend a lower or higher percentage of the transfer received.Footnote6 The only significant relationship is between knowledge of the current inflation rate and the choice to spend/save out of the money transfer. Respondents who are aware of the current level of inflation are more inclined to save a larger part of the money transfer and spend less, i.e. 21% of the total transfer compared to 28% for the whole sample.

The recent literature on consumption (discussed by Muellbauer Citation2016) suggests that consumption does not only depend on income but also on the level and composition of households’ wealth. To investigate the relationship between the respondents’ intended allocation of a €2000 transfer by the ECB and their financial situation, we created tertiles for respondents based on their personal income, household net wealth, liquid assets as a percentage of total assets and dummies for pension fund membership, home ownership and having an ‘under water’ mortgage, i.e. a mortgage loan exceeding the value of the home.

, which reports bivariate relations, suggests that respondents with low income or wealth levels intend to spend a larger percentage of the transfer while respondents with high income and wealth intend to use a larger percentage to repay debt or donate money. Similarly, homeowners intend to use a larger percentage of the transfer to redeem debt – and accordingly spend less – than respondents who rent a house.Footnote7 Nevertheless, the differences between the various groups of respondents are small and mostly insignificant and the percentage of the transfer that would be spent varies within a narrow range of 23% to 32%. In a multivariate regression analysis where we simultaneously control for these income and wealth measures in addition to some standard socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age and education) following previous studies like Jappelli and Pistaferri (Citation2014), Christelis et al. (Citation2018), and Fuster, Kaplan, and Zafar (Citation2018), we also find mostly insignificant coefficients (see Appendix 2). Specifically, for spending, we find a 5 percentage points lower marginal propensity to spend for respondents with high net wealth (significant at the 10% level).

Table 5. The impact of income and wealth on allocation of €2000 transfer from ECB.(Weighted average allocation in euros; percentages of total amount in parentheses)

Would helicopter money affect expectations?

In the questionnaire, we ask respondents how they expect helicopter money would affect economic growth, inflation and wage increases, respectively.Footnote8 A similar question refers to the impact of QE. Note that these questions were asked after explaining the concepts of QE and helicopter money (see the questionnaire in Appendix 1). reports the results. Between 25% and 30% of the respondents expect (much) higher inflation. This group of respondents is twice as large as the group expecting (much) lower inflation. Thus, on balance helicopter money seems to slightly increase inflation expectations. However, according to the respondents, helicopter money would primarily affect economic growth expectations. Almost half of the respondents expect helicopter money to increase economic growth (but a small group foresees lower economic growth). Most respondents expect no impact on wages. The ING study reports similar results for the European consumer, i.e. helicopter money would more often affect economic growth expectations than inflation expectations (Bright and Janssen Citation2017). However, for the Dutch respondents in their survey, the group expecting higher inflation (4 in 10 respondents) is roughly equal in size as the group expecting higher economic growth.

Table 6. Perceived impact of helicopter money and QE.(Weighted percentages of respondents)

Comparing the perceived impact of QE and helicopter money, respectively, on inflation, economic growth and wages, we find some interesting similarities and differences. Similar to our findings for helicopter money, more respondents expect a positive impact of QE on economic growth than on inflation. However, compared to helicopter money expectations for all economic variables are less affected by QE; almost half of the respondents report not to know what to expect from QE. Most likely, the channels through which central bank purchases of securities affect the economy are less appealing to the public than the transmission channels of money transfers. Indeed, further analysis reveals that respondents who have heard about QE are more likely to expect an increase in inflation as a consequence of QE (results available on request).

Trust in the ECB

Compared to other European and national institutions, many people put high trust in the ECB (cf. Ehrmann, Soudan, and Stracca Citation2013). However, trust in the ECB has declined after the onset of the financial crisis (Wälti Citation2012; Bursian and Fürth Citation2015). This is worrisome because trust in ECB supports the anchoring of inflation expectations around the ECB target of below but close to 2% (Christelis et al. Citation2016). A concern about QE and helicopter money is that these measures may further undermine the public’s confidence in the ECB. shows the impact of several factors on respondents’ trust in the ECB.Footnote9 The results suggest that the effect of helicopter money on public trust in the ECB is ambiguous. Helicopter money increases trust in ECB for almost 1 in 5 respondents, but decreases trust for 1 in 5 respondents as well. For the large majority, helicopter money does not change trust or respondents do not know yet whether their trust in the ECB would be affected.

Table 7. What is the effect on trust in the ECB of …. ?.(Weighted percentages of respondents)

The results suggest that ECB policies to purchase government and corporate debt reduce trust in the ECB somewhat more than does helicopter money. For instance, 23% of the respondents state that buying government debt lowers their trust in the ECB, compared to 16% reporting increased trust. These percentages are 30 and 13 respectively if we ask for the effect on trust if the ECB buys corporate debt. An additional adverse effect on trust in the ECB would occur if QE leads to negative interest rates on consumer savings accounts. Also, negative mortgage rates would lower trust in the ECB. Conversely, the asset quality review of banks by the ECB had a positive impact on trust.

One might argue that these findings reflect a lack of understanding of what helicopter money does and that the attitudes of respondents would become more positive when they are informed about the purpose of helicopter money. While we did not perform this experiment, the data allow us to explore the support for helicopter money among those who are more knowledgeable (i.e. are familiar with the terms helicopter money or QE). We find that among the knowledgeable the effect of helicopter money on trust is significantly more negative than in the whole sample. Specifically, helicopter money would reduce trust in the ECB for 46% of knowledgeable respondents (results available on request).

Discussion

There are several issues that need to be taken into account in interpreting our findings. First, in the survey, we do not explicitly consider the prevailing economic circumstances at the time when the survey was conducted. Therefore, it is likely that the survey respondents answered the questions while considering their current economic circumstances. When the survey was conducted (13 to 24 May 2016) the Dutch economy was slowly recovering from the fall-out of the financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis. Recovery was slower than in some other European countries like Germany. Still, at the time, the Netherlands were not in a recession any more. It seems likely that under more stressed economic circumstances consumers would spend more and that our results may, therefore, be attenuated by the prevailing, relatively strong economic conditions.

Second, we have focused on whether or not consumers would spend the money received. However, if people spend unexpected money transfers on durables, this may be considered as savings since part of the durables bought otherwise would be consumed at a later point in time. Indeed, as pointed out above, the results of Kuhn et al. (Citation2011) suggest that Dutch citizens‘ consumption responds little following unanticipated transitory income shocks, such as lottery wins, as most of the windfall income received is spent on durables.Footnote10 We have not asked respondents how they intend to spend the money, as we believe that whether or not people would spend the money determines the macroeconomic impact of a helicopter drop, no matter whether it would be spent on durables or non-durables.Footnote11

Third, our results suggest that a small part of the money received under a helicopter drop would be donated. We decided to include this category to have a more complete picture of the answer options, as respondents may be more willing to use an unexpected windfall than regular income sources for donations to e.g. charity. As to the results: on the one hand, this outcome seems to give the answers more credibility as the answers given are likely quite honest. On the other hand, it may lead to an underestimate of the marginal propensity to spend if the money donated would be spent by the receiver. However, even if we assume that also money donated would be fully spent, our results do not suggest that the marginal propensity to spend out of a helicopter drop is between about 40% and 60% as suggested by Muellbauer (Citation2014). Nevertheless, the total impact on aggregate spending may be larger than the immediate impact found in our survey if households would spend part of the savings out of the helicopter transfer in the longer term. Respondents who indicate that they will save the money might spend it after a couple of months when they are confronted with an unexpected expense. Such cases would increase the impact on spending if respondents otherwise could not have afforded this expense.

Fourth, it has been argued that in surveys like ours the order of asking questions may affect the outcomes. However, our experience with randomizing answer options in this sort of questions in internet surveys is that ordering effects do not play a role. We found it more important to randomize the order of questions referring to the institute ‘ECB’ versus ‘government’ and the size of the amount ‘€500’ versus ‘€2000’. In both cases, the results showed no question order effects on responses. Note further, that the order of the answers in these questions is such that the first option is ‘donate’ and the last option is ‘other’. While these options are suspicious to gaining higher weight by respondents (due to primacy or recency effects), these options were given a non-zero number only infrequently. Moreover, respondents were shown a table on the screen with all six options and had to fill in an amount for each of these options (which amounts had to sum up to the total amount) which makes response order effects less likely.

Fifth, would respondents tell the truth and would they behave in the same way as they report in our survey? Carlsson and Kataria (Citation2018) test a self-commitment mechanism where survey respondents are asked to promise to answer the survey questions truthfully. They find that differences between answers given in surveys with and without this promise are rather small. Likewise, there is evidence suggesting that respondents often behave as they say they would. For instance, survey measures of risk tolerance have been shown to predict risky health behaviour such as smoking and drinking (Barsky et al. Citation1997). Other examples include Hurd, van Rooij, and Winter (Citation2011) who show that respondents with expectations of positive stock market returns are more likely to enter the stock market or Hurd, Smith, and Zissimopoulos (Citation2004) who show that self-reports on longevity are predictive for the decision when to claim retirement benefits in the US. In a more recent example, Armantier et al. (Citation2015) document evidence from incentivised experiments of individuals who act in line with their inflation expectations as reported in earlier surveys. Nevertheless, consumers may spend more than they plan upfront or respondents may change their mind if unanticipated shocks occur. Sahm, Shapiro, and Slemrod (Citation2010) investigate the reliability of survey reports on intended spending before a US tax rebate by re-interviewing the respondents a couple of months after they had received the rebate. In both surveys, about a fifth of the respondents indicated to spend or have spent most of the rebate. Indeed, comparing individual responses, the majority of respondents had acted upon their intentions. Among respondents who switched to more or to less spending in the second survey, personal circumstances were the most reported cause for this switch. Thus, in absence of economy-wide, unanticipated shocks affecting many consumers in a similar way, actual spending quite accurately matched intended spending.

Finally, to what extent are the results of our survey among Dutch citizens representative for the euro area as a whole? As pointed out before, the results of two other recent studies are close to our findings. Bright and Janssen (Citation2017) report that in their survey among citizens of 12 European countries only 26% of the respondents say they would spend most of the money. The marginal propensity to spend reported by Djuric and Neugart (Citation2016) based on a survey among German citizens is somewhat higher (40%).

V. Concluding comments

There are many proclaimed pros and cons of helicopter money. According to Turner (Citation2015), ‘we should recognize that there is an undoubted technical case for using monetary finance in some circumstances, and now address the political issue of how to make ensure that it will only be used in appropriate circumstances and appropriately moderate quantities.’ In our view, support among European policymakers for the idea seems extremely low at the moment of writing, no matter whether the drop would be done by the ECB or national governments. The latter option may be even more problematic than the first in view of the prohibition of monetary financing of government spending by the ECB. Still, when the next recession will hit and unconventional policies like those currently used are considered insufficient, views among policymakers may change.

In a survey in the Netherlands, we have asked participants how they would allocate a transfer received from either the ECB or the national government; to examine whether the size of the transfer matters, we asked the same question for two amounts of the transfer (€500 and €2000). Note that a money transfer of €2000 to every citizen aged 18 years or older in the 19 euro-area countries would sum to a total amount of about €550 billion which is about equivalent to the total amount of securities purchased under EAPP within a seven-month period (that is in the period that monthly purchases equalled €80 billion). Our findings suggest that only a part of this money transfer would actually be spent. Also, helicopter money would have a limited direct impact on inflation expectations among the public. Given the limited effects on spending, second round effects on inflation expectations would most likely be limited as well.

The impact of unconventional monetary policy on trust in the ECB seems mixed (in the case of helicopter money) or somewhat negative (for QE). It thus seems that the public does not consider helicopter money and QE as effective measures to increase inflation. Indeed, most respondents indicate that they do not raise their inflation expectations in response to these measures.

Our results show that respondents expect to spend about 30% of the money transfer instead of using the full amount to increase spending. Should we be surprised by this marginal propensity to spend (MPS) level? On the one hand, stylized theoretical models suggest a much lower MPS of 3–5% out of transitory income shocks. On the other hand, more realistic models incorporating liquidity constraints and precautionary saving as well as many of the empirical estimates in the literature, among others based on tax rebates, are broadly in line with our findings (for an overview see, e.g. Jappelli and Pistaferri Citation2010, Citation2014).

Our finding that the impact of a helicopter transfer is very similar for transfers coming from the ECB or the government runs against the view of Muellbauer (Citation2014). Consequently, if central banks were to consider helicopter money, there would be no need in terms of effectiveness for the ECB to distribute the money transfers rather than channel these transfers through the governments. In fact, given the resemblance of helicopter money and fiscal policy it may be preferable that fiscal authorities transfer the helicopter money.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of DNB. The authors thank Michael Weber, Jan Marc Berk, Christiaan Pattipeilohy and the referee for their comments on a previous version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 See, for instance, Buiter (Citation2014), Turner (Citation2015) and Bernanke (Citation2016). See also Reichlin, Turner, and Woodford (Citation2013) and Karakas (Citation2016) for overviews. Peter Praet, a member of the ECB’s Governing Council, noted, ‘All central banks can do it. The question is, if and when is it opportune.’ According to Richard Clarida, ‘We will see a variant of helicopter money (perhaps thinly disguised) in the next 10 years if not the next five.’ (Both cited in Ipp Citation2016).

2 English, Erceg, and Lopez-Salido (Citation2017) explore the possible effects of such policies. While they do find that money-financed fiscal programs could provide significant stimulus, they underscore the risks that would be associated with such a program. These risks include persistently high in inflation if the central bank fully adhered to the program; or alternatively, that such a program would be ineffective in providing stimulus if the public doubted the central bank’s commitment to such a strategy.

3 D’Acunto, Hoang, and Weber (Citation2016) examined how German households reacted when the German government announced in November 2005 an unexpected 3-percentage-point increase in value-added tax (VAT) that would become effective in 2007. Households’ willingness to purchase durables increased by 34% after the shock, compared to before and to matched households in other European countries that were not exposed to the VAT shock. Hayo and Uhl (Citation2017) also study the effect of an exogenous tax reduction in Germany using survey data and find that high-income households are more likely to increase spending in response to tax changes.

4 A lower marginal propensity to spend out of a higher money transfer may be due to a higher number of liquidity constrained consumers overcoming this constraint as shown by Christelis et al. (Citation2018). It is also consistent with the concavity of the consumption function due to income uncertainty (Carroll and Kimball Citation1996).

5 Given the small variation in allocation patterns in , we focus on the results of a €2000 money transfer by the ECB in the remainder of the paper. The results for government transfers or a €500 money transfer by the ECB are available on request.

6 For 5 out of 6 proxies for knowledge, we find that respondents with knowledge allocate a significant higher percentage of the €2000 money transfer to investments than respondents without knowledge. This is consistent with the relation between financial knowledge and stock market participation (Van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie Citation2011). However, also knowledgeable respondents use only a small percentage of the money transfer for investments.

7 Falling home prices in the aftermath of the financial crisis in combination with the custom of first-time buyers to take out high mortgages (see Van Ooijen and van Rooij Citation2016) resulted in many homeowners facing loan to value ratios of over 100% with an interest in redeeming mortgage debt. Indeed, debt redemption is an important motive for saving in the Netherlands (Le Blanc et al. Citation2016).

8 Arguably, respondents may find expectation questions on macroeconomic variables difficult to answer. However, Dräger, Lamla, and Pfajfar (Citation2016) document that a substantial share of consumers reports macroeconomic expectations that are consistent with important economic concepts such as the Fisher equation, the Taylor rule and the Phillips curve.

9 Following previous studies, we did not provide respondents with a definition of trust. So respondents might have very different notions of “trust” when answering to the survey. In particular, it is important to note that our survey does not ask whether respondents trust that the ECB delivers on its mandate.

10 We have not asked how respondents would spend lottery wins, but Djuric and Neugart (Citation2016) find that in all policy treatments for helicopter money people consider helicopter money as a windfall and spend the same amount they would spend out of a lottery win.

11 Christelis et al. (Citation2018) ask Dutch respondents how they would allocate a one-time bonus equal to one month or three months of income over four possible categories (saving, repaying debt, purchasing non-durables and purchasing durables) in the next 12 months. They find that total spending out of this windfall gain equals 37–39% of the bonus. While the difference is not very large, total spending is somewhat higher than in our survey, which may be related to the explicit distinction between durables and non-durables.

References

- Agarwal, S., and W. Qian. 2014. “Consumption and Debt Response to Unanticipated Income Shocks: Evidence from A Natural Experiment in Singapore.” The American Economic Review 104: 4205–4230.

- Alessie, R., S. Hochguertel, and A. van Soest. 2002. “Household Portfolios in the Netherlands.” In Household Portfolios, edited by L. Guiso, M. Haliassos, and T. Jappelli, 340–388. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Armantier, O., W. Bruine de Bruin, G. Topa, W. van der Klaauw, and B. Zafar. 2015. “Inflation Expectations and Behavior: Do Survey Respondents Act on Their Beliefs?” International Economic Review 56: 505–536.

- Aron, J., J. Duca, J. Muellbauer, K. Murata, and A. Murphy. 2012. “Credit, Housing Collateral and Consumption in the UK, U.S., And Japan.” Review of Income and Wealth 58 (3): 397–423.

- Barsky, R., F. Juster, M. Kimball, and M. Shapiro. 1997. “Preference Parameters and Behavioural Heterogeneity: An Experimental Approach in the Health and Retirement Study.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 112: 729–758.

- Bernanke, B. 2002. Deflation: Making Sure ‘It‘ Doesn‘T Happen Here. Washington, D.C.: Remarks before the National Economists Club. November 21.

- Bernanke, B. 2016. What Tools Does the Fed Have Left? Part 3: Helicopter Money. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Blinder, A., M. Ehrmann, J. de Haan, and D. Jansen. 2017. “Necessity as the Mother of Invention: Monetary Policy after the Crisis.” Economic Policy 32: 707–755.

- Blinder, A., M. Ehrmann, M. Fratzscher, J. de Haan, and D. Jansen. 2008. “Central Bank Communication and Monetary Policy: A Survey of Theory and Evidence.” Journal of Economic Literature 46 (4): 910–945.

- Borio, C., P. Disyatat, and A. Zabai. 2016. “Helicopter Money: The Illusion of a Free Lunch.” VoxEU. http://voxeu.org/article/helicopter-money-illusion-free-lunch

- Bright, I., and S. Janssen. 2017. “Helicopter Money: Loved, Not Spent.” VoxEU. http://voxeu.org/article/helicopter-money-loved-not-spent

- Broda, C., and J. Parker. 2008. The Impact of the 2008 Tax Rebates on Consumer Spending: Preliminary Evidence. Mimeo, Chicago: University of Chicago Graduate School of Business.

- Buiter, W. 2014. “The Simple Analytics of Helicopter Money: Why It Works – Always.” Kiel Institute for the World Economy Economics Discussion Paper 2014-24. http://www.economics-ejournal.org/economics/discussionpapers/2014-24

- Bursian, D., and S. Fürth. 2015. “Trust Me! I Am a European Central Banker.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 47 (8): 1503–1530.

- Carlsson, F., and M. Kataria. 2018. “Do People Exaggerate How Happy They Are? Using a Promise to Induce Truth-Telling.” Oxford Economic Papers 70 (3): 784–798.

- Carroll, C., and M. Kimball. 1996. “On the Concavity of the Consumption Function.” Econometrica 64 (4): 981–992.

- Chauvin, V., and J. Muellbauer. 2013. “Consumption, Household Portfolios and the Housing Market: A Flow of Funds Approach for France.” Presented at Banque de France, December. http://www.touteconomie.org/afse2014/index.php/meeting2014/lyon/paper/viewFile/413/7

- Christelis, D., D. Georgarakos, and T. Jappelli. 2015. “Wealth Shocks, Unemployment Shocks and Consumption in the Wake of the Great Recession.” Journal of Monetary Economics 72: 21–41.

- Christelis, D., D. Georgarakos, T. Jappelli, L. Pistaferri, and M. van Rooij. 2018. “Asymmetric Consumption Effects of Transitory Income Shocks”. Forthcoming in. The Economic Journal.

- Christelis, D., D. Georgarakos, T. Jappelli, and M. van Rooij. 2016. “Trust in the Central Bank and Inflation Expectations.” DNB Working Paper 537.

- D’Acunto, F., D. Hoang, and M. Weber. 2016. “The Effect of Unconventional Fiscal Policy on Consumption Expenditure.” NBER Working Paper 22563.

- de Haan, J., and J.-E. Sturm. 2019. “Central Bank Communication: How to Manage Expectations?.” Forthcoming in. In Handbook on the Economics of Central Banking, edited by D. Mayes, P. Siklos, and J.-E. Sturm, Oxford. Oxford University Press, 231-262.

- de Haan, J., M. Hoeberichts, R. Maas, and F. Teppa. 2016. Inflation in the Euro Area and Why It Matters. De Nederlandsche Bank Occasional Study, Amsterdam.

- Deuflhard, F., D. Georgarakos, and R. Inderst. 2019. “ Literacy and Savings Account Returns”.” In Journal of European Economic Association, 17 : 131-164.

- Djuric, U., and M. Neugart. 2016. Helicopter Money: Survey Evidence on Expectation Formation and Consumption Behavior. Darmstadt, Germany: Mimeo.

- Dräger, L., M. J. Lamla, and D. Pfajfar. 2016. “Are Survey Expectations Theory-Consistent? the Role of Central Bank Communication and News.” European Economic Review 85: 84–111.

- Ehrmann, M., M. Soudan, and L. Stracca. 2013. “Explaining European Union Citizens’ Trust in the European Central Bank in Normal and Crisis Times.” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 115 (3): 781–807.

- English, W., C. Erceg, and D. Lopez-Salido. 2017. “Money-Financed Fiscal Programs: A Cautionary Tale.” Hutchins Center Working Paper 31.

- Fagereng, A., M. B. Holm, and G. L. Natvik. 2016. “MPC Heterogeneity and Household Balance Sheets.” https://ssrn.com/abstract=2861053

- Fuster, A., G. Kaplan, and B. Zafar. 2018. “What Would You Do with $500? Spending Responses to Gains, Losses, News and Loans.” NBER Working Paper 24386.

- Gali, J. 2014. The Effects of a Money-Financed Fiscal Stimulus. Barcelona: Mimeo.

- Hayo, B., and E. Neuenkirch. 2018. “The Influence of Media Use on Layperson Monetary Policy Knowledge in Germany.” Scottish Journal of Political Economy 65 (1): 1–26.

- Hayo, B., and M. Uhl. 2017. “Taxation and Consumption: Evidence from a Representative Survey of the German Population.” Applied Economics 49 (53): 5477–5490.

- Hurd, M., J. Smith, and J. Zissimopoulos. 2004. “The Effects of Subjective Survival on Retirement and Social Security Claiming.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 19: 761–775.

- Hurd, M., M. van Rooij, and J. Winter. 2011. “Stock Market Expectations of Dutch Households.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 26: 416–436.

- Ipp, G. 2016. “The Time and Place for ‘Helicopter Money’.” http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2016/03/21/the-time-and-place-for-helicopter-money/

- Jappelli, T., and L. Pistaferri. 2010. “The Consumption Response to Income Changes.” Annual Review of Economics 2 (1): 479–506.

- Jappelli, T., and L. Pistaferri. 2014. “Fiscal Policy and MPC Heterogeneity.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 6 (4): 107–136.

- Johnson, D., J. Parker, and N. Souleles. 2006. “Household Expenditure and the Income Tax Rebates of 2001.” American Economic Review 96 (5): 1589–1610.

- Kaplan, G., and G. Violante. 2014. “A Model of the Consumption Response to Fiscal Stimulus Payments.” Econometrica 82 (4): 1199–1239.

- Karakas, C. 2016. Helicopter Money: A Cure for What Ails the Euro Area?. Brussels: European Parliamentary Research Service.

- Kuhn, P., P. Kooreman, A. Soetevent, and A. Kapteyn. 2011. “The Effects of Lottery Prizes on Winners and Their Neighbors: Evidence from the Dutch Postcode Lottery.” American Economic Review 101 (5): 2226–2247.

- Le Blanc, J., A. Porpiglia, F. Teppa, J. Zhu, and M. Ziegelmeyer. 2016. “Household Saving Behaviour in the Euro Area.” International Journal of Central Banking 12 (2): 15–69.

- Leigh, A. 2012. “How Much Did the 2009 Australian Fiscal Stimulus Boost Demand? Evidence from Household-Reported Spending Effects.” The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics 12 (1). (Contributions), Article 4.

- Lusardi, A., and O. Mitchell. 2014. “The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence.” Journal of Economic Literature 52 (1): 5–44.

- Muellbauer, J. 2014. “Combatting Eurozone Deflation: QE for the People.” VoxEU. http://voxeu.org/article/combatting-eurozone-deflation-qe-people

- Muellbauer, J. 2016. “Macroeconomics and Consumption.” CEPR Discussion Paper 11588.

- Parker, J., N. Souleles, D. Johnson, and R. McClelland. 2013. “Consumer Spending and the Economic Stimulus Payments of 2008.” American Economic Review 103 (6): 2530–2553.

- Reichlin, L., A. Turner, and M. Woodford. 2013. “Helicopter Money as a Policy Option.” VoxEU. http://www.voxeu.org/article/helicopter-money-policy-option

- Reis, R. 2015. “Different Types of Central Bank Insolvency and the Central Role of Seignorage.” CEPR Discussion Paper 10693.

- Rosengren, E. 2015. “Lessons from the U.S. Experience with Quantitative Easing.” Speech at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Moody’s Investors Service‘s 8th Joint Event on Sovereign Risk and Macroeconomics. Frankfurt am Main. 5 February 2015.

- Sahm, C., M. Shapiro, and J. Slemrod. 2010. “Household Response to the 2008 Tax Rebates: Survey Evidence and Aggregate Implications.” In Tax Policy and the Economy, edited by J. Brown, 69–110. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Teppa, F., and C. Vis. 2012. “The CentERpanel and the DNB Household Survey: Methodological Aspects.” DNB Occasional Studies 10 (4). De Nederlandsche Bank.

- Turner, A. 2015 November. “The Case for Monetary Finance – An Essentially Political Issue.” 16th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference, Washington (DC).

- Van der Cruijsen, C., D. Jansen, and J. de Haan. 2015. “How Much Does the Public Know about the ECB’s Monetary Policy? Evidence from A Survey of Dutch Households.” International Journal of Central Banking 11 (4): 169–218.

- Van Ooijen, R., and M. van Rooij. 2016. “Mortgage Risk, Debt Literacy and Financial Advice.” Journal of Banking and Finance 72: 201–217.

- Van Rooij, M. C. J., A. Lusardi, and R. J. M. Alessie. 2011. “Financial Literacy and Stock Market Participation.” Journal of Financial Economics 101: 449–472.

- Van Rooij, M. C. J., A. Lusardi, and R. J. M. Alessie. 2012. “Financial Literacy and Retirement Planning in the Netherlands.” The Economic Journal 122: 449–478.

- Wälti, S. 2012. “Trust No More? the Impact of the Crisis on Citizens’ Trust in Central Banks.” Journal of International Money and Finance 31: 593–605.

- Williams, J. 2014. “Monetary Policy at the Zero Lower Bound: Putting Theory into Practice.” Paper presented at the Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy at Brookings, Washington (DC).

Appendix 1.

The Survey

Below, we explain the structure and precise wording of the most important questions in our survey.

Structure of the questionnaire

Our sample of respondents was randomly split into four groups. Group 1 was offered question Q1a, group 2 was offered question Q1b, and so forth. Note that respondents could cross an ‘I do not know’ option when answering this question. Next, all respondents answer question Q2. Thereafter, each group was offered a similar question as in Q1a-d, but now with ‘European Central Bank’ replaced by ‘government’ and vice versa. Next, all respondents answer a question similar to question Q2 and all questions thereafter are offered to all respondents as well.

Wording of questions

The question numbers refer to the actual order in the survey.

Q1a) Imagine that the European Central Bank (ECB) deposits €500 on the bank account of each citizen aged 18 years and older in the euro area. What would you do with this money?

Please divide €500 between the following categories:

- Donate (e.g. to a good cause or relative)

- Spend on groceries, furniture, vehicles, trips, vacation or other expenses

- Put aside (e.g. on a savings account)

- Invest (e.g. in stocks)

- Redeem mortgage or other debt

- Other

Q1b) Imagine that the European Central Bank (ECB) deposits €2000 on the bank account of each citizen aged 18 years and older in the euro area. What would you do with this money?

Please divide €2000 between the following categories:

- Donate (e.g. to a good cause or relative)

- Spend on groceries, furniture, vehicles, trips, vacation or other expenses

- Put aside (e.g. on a savings account)

- Invest (e.g. in stocks)

- Redeem mortgage or other debt

- Other

Q1c) Imagine that the government of each country in the euro area deposits €500 on the bank account of each citizen aged 18 years and older in the euro area. What would you do with this money?

Please divide €500 between the following categories:

- Donate (e.g. to a good cause or relative)

- Spend on groceries, furniture, vehicles, trips, vacation or other expenses

- Put aside (e.g. on a savings account)

- Invest (e.g. in stocks)

- Redeem mortgage or other debt

- Other

Q1d) Imagine that the government of each country in the euro area deposits €2000 on the bank account of each citizen aged 18 years and older in the euro area. What would you do with this money?

Please divide €2000 between the following categories:

- Donate (e.g. to a good cause or relative)

- Spend on groceries, furniture, vehicles, trips, vacation or other expenses

- Put aside (e.g. on a savings account)

- Invest (e.g. in stocks)

- Redeem mortgage or other debt

- Other

Q2) What do you think are the consequences of this measure for economic growth, inflation and wages of employees? DK = I do not know

Q3a-Q3d) similar to Q1a-Q1d, but now with ‘European Central Bank’ replaced by ‘government of each country in the euro area’ and vice versa (see above for a description of the structure of the survey)

Q4) is identical to Q2

Q5) Money deposited by the European Central Bank (ECB) on citizens’ bank accounts (directly or via the government) is called helicopter money. Have you ever heard about ‘helicopter money’ before?

[] Yes

[] No

Q6) The European Central Bank (ECB) purchases government bonds (government debt) as of March 2015 and will start purchasing corporate bonds (corporate debt) on the financial markets soon. This is called quantitative easing. Have you ever heard about quantitative easing (or QE) before?

[] Yes

[] No

Q7) is identical to Q2

Q8) For you personally, do the measures or developments below lead to less, equal or more trust in the European Central Bank (ECB)?

Q9) Who is the president of the European Central Bank (ECB)? We are interested in your first thought. You do not need to be sure about your answer and you are not supposed to look up the answer.

[] Jeroen Dijsselbloem

[] Mario Draghi

[] François Hollande

[] Jean-Claude Juncker

[] Klaas Knot

[] Christine Lagarde

[] Angela Merkel

[] Mark Rutte

[] Jean-Claude Trichet

[] Nout Wellink

[] I do not know

Q10) What are the main goals and tasks of the European Central Bank (ECB)? We are interested in your first thought. You do not need to be sure about your answer and you are not supposed to look up the answer. You may cross multiple answers.

[] High economic growth

[] High wages

[] Low unemployment

[] Price stability

[] Supervision of banks

[] I do not know

Q11) What do you think is the current rate of inflation in the Netherlands? If you think the inflation rate is negative, you can provide a negative percentage using the minus sign (-). You may provide a percentage answer up to 1 digit after the comma. Please provide an estimate if you are not sure about your answer. You are not supposed to look up the answer.

[] . percent

[] I do not know

Appendix 2.

Multivariate Regressions

Instead of the bivariate statistics for the allocation of the €2000 helicopter transfer across various income and wealth subgroups reported in , presents a multivariate regression analysis where we simultaneously control for these income and wealth measures in addition to standard socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age and education).

Table A1. Multivariate analysis of the allocation of €2000 transfer from ECB.