?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The expansion of health insurance in emerging countries raises concerns about the unintended negative effects of health insurance on labour supply. This article examines the labour supply effects of the Health Care Fund for the Poor (HCFP) in Vietnam in terms of the number of work hours per month and labour force participation (the probability of employment). Employing various matching methods combined with a Difference-in-Differences approach on the Vietnam Household Living Standard Surveys 2002–2006, we show that the HCFP, which aims to provide poor people and disadvantaged minority groups with free health insurance, has a negative effect on labour supply. This is manifested in both the average number of hours worked per month and the probability of employment, suggesting the income effect of the HCFP. Interestingly, the effects are mainly driven by the non-poor recipients living in rural areas, raising the question of the targeting strategy of the programme.

I. Introduction

The expansion of public health insurance to the poor and vulnerable has received a large amount of attention because of its potential effects on reducing catastrophic out-of-pocket spending and increasing access to health care (Lagomarsino et al. Citation2012). Such impacts are particularly important for the poor who normally cannot afford to pay out-of-pocket. These are hence especially desirable for many low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) with a large proportion of poor population who normally do not have the financial resources to buy health insurance (ibid.). Many emerging economies in Asia, Latin America and Africa are making progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC) to reduce the financial hardship for those seeking health care (Rodin and de Ferranti. Citation2012; Lagomarsino et al. Citation2012). The momentum on achieving UHC is rather strong as many countries have increased or committed to increase government spending on total health expenditure (Lagomarsino et al. Citation2012). The ambition towards UHC has also received support and active participation from important donors and international organizations (ibid.).

However, there have been concerns about the unintended labour market consequences of health insurance in general and health insurance for the low-income population in particular. For instance, it has been shown that social health insurance expansion in East Europe and Central Asia during 1990–2004 has been associated with higher unemployment (Wagstaff and Moreno-Serra Citation2009) and reduced aggregate employment (Wagstaff and Moreno-Serra Citation2015) while increasing the aggregate share of self-employment (ibid.). Even though the authors failed to control for political changes which potentially caused unemployment, their findings provoked some debate on the potential negative impacts of health insurance on the labour market. From a theoretical perspective, the theory of static labour supply (Chou, Liu, and Hammitt Citation2002; Rosen Citation2014) predicts a negative labour supply effect of health insurance which is not tied to employment due to the income effect.

In the context of the UHC movement, there has been a renewed interest in the labour supply effects of health insurance. However, there is currently inadequate and inconclusive evidence on the topic. A recent systematic review on the topic (Lê et al. Citation2019) suggests that empirical evidence in LMIC is relatively scarce and sporadic probably due to data limitations. The existing literature on the labour supply effects of pro-poor health insurance programmes is mainly represented by studies on the American healthcare system, where the evidence is mixed (ibid.), whereas, the evidence beyond the United States is very limited (ibid.). This creates a knowledge gap, especially for LMIC where health insurance coverage is expanding. Therefore, to fill this gap, it is necessary to seek for more evidence to guide policy making.

In Vietnam, this is crucially relevant as health coverage is being expanded rapidly with assertive political commitment which has been translated into recent legal documents such as the Health Insurance Law versions of 2008 and 2014. In its latest strategic document, the government aims at a coverage rate of more than 90 per cent by 2020 (Socialist Republic of Vietnam Citation2016).

This article investigates the effects of the Health Care Fund for the Poor (hereafter, HCFP) on the labour supply of the beneficiaries in Vietnam. Using pre-treatment matching techniques combined with a Difference-in-Differences approach on a panel of Vietnam Household Living Standards Surveys (VHLSS) during 2002–2006, we evaluate the labour supply effects of the programme in terms of monthly work hours and the probability of working. We separate the effects for urban and rural individuals as well as the poor and non-poor people among the treated individuals. This article contributes to filling the gap in our knowledge on the impact of health insurance on the labour supply and presents empirical evidence on this sporadically researched topic in the context of LMIC.

II. Literature review

The potentially distorting effects of health insurance and welfare benefits have been discussed thoroughly in theory. The budget constraint approach argues that government-provided health insurance, as financed by tax, is similar to a welfare benefit and hence can be considered as a positive income shock for low-income individuals and those who have high health expenses (Boyle and Lahey Citation2010). Therefore, a non-contributory health scheme may reduce labour supply due to the income effect.

Similarly, the static labour supply theory states that individuals make a trade-off between labour supply and leisure at a given wage level (Chou and Staiger Citation2001; Rosen Citation2014). Therefore, the provision of welfare benefits increases household income but also potentially reduces labour force participation (Rosen Citation2014). Importantly, as argued by Chou and Staiger (Citation2001), the income effect of non-contributory health insurance may be stronger than that of other welfare benefits as it not only increases income (in the form of the subsidy) but also reduces variation in consumption resulting from the removal of unexpected catastrophic health expenses. Therefore, compulsory health insurance which is not tied to employment may make paid work less attractive due to the consumption smoothing (Chou and Staiger Citation2001). The magnitude of the income effect, however, depends on the share of health expenses in total household expenses (ibid.).

Despite being used widely, these theories implicitly use a broad definition of welfare benefits which also includes public health insurance. Therefore, the income effect of health insurance is viewed similarly to that of other social transfers which normally have a more direct income push. In the context of LMIC, this direct income effect of public health insurance is not always as obvious as in the case of cash transfers due to the negligible health premiums of many public schemes (e.g. in Vietnam the annual premium of health insurance for the poor in 2003 under HCFP was little more than 2.5 USD). Besides, the assumption of removal of catastrophic health costs is not always warranted, as this depends on the breadth and depth of the coverage.

In addition, there are concerns about moral hazard arising from welfare programmes. Gruber (Citation2010) argues that non-contributory welfare provision is negatively correlated with labour supply as it ‘raises the incentive for individuals to be poor’ in order to qualify for the benefits (Gruber Citation2010, 500). It is important to note that Gruber’s definition refers to the American welfare system wherein welfare benefits also contain medical care (Gruber Citation2010, chapter 17). Therefore, his argument is not only applicable to in-cash and in-kind transfers but also health insurance for the poor, particularly Medicaid in the United States. Even though this view has been considered debatable (Banerjee et al. Citation2017), it seems consistent with theoretical predictions which suggest that increased welfare may draw more people into welfare programmes while not inducing them to leave (see the models in Ham and Shore-Sheppard Citation2005; Strumpf Citation2011).

These theoretical arguments indicate a negative effect of health insurance on labour supply. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasise that these models are framed in the context of Medicaid in the United States and might not be applicable to LMIC. They seem to ignore the in-kind benefits of health insurance which potentially have a positive health impact on recipients. With better access to healthcare, the poor may become healthier, more productive and hence can work more to increase their income. This health fostering argument combined with a human rights based approach is widely used by UHC proponents. Nevertheless, data on health status are normally unavailable in labour market surveys to test this hypothesis (Strumpf Citation2011). Additionally, the empirical evidence of the effects of health insurance on health is rather thin, especially for adults (Sommers, Baicker, and Epstein Citation2012). Furthermore, the health-improvement assumption does not always hold true because health insurance is not easily translated into better health (Levy and Meltzer Citation2004), as this depends on the generosity of the coverage as well as the infrastructure availability.

The empirical literature on the labour supply effects of health insurance in LMIC is rather limited. According to a recent systematic review (Lê et al. Citation2019), 47 out of 63 post-2000 publications reviewed are about the United States. Similarly, the literature with a particular focus on low-income recipients is mainly concentrated on the United States, with mixed results (ibid.). Rosen (Citation2014) shows that those without Medicaid tend to work around six hours more per week while an increase in eligibility reduces the employment likelihood by 1.7–7.2 percentage points (Dave et al. Citation2015). Other studies, however, find insignificant results of Medicaid introduction and expansion on labour supply in terms of work hours (Gooptu et al. Citation2016) and labour force participation (Strumpf Citation2011; Ham and Shore-Sheppard Citation2005). This inconclusive result is also confirmed by another review by Gruber and Madrian (Citation2002) who reviewed the U.S. literature published before 2000.

There is no study for Vietnam on the labour supply effects of health insurance for the poor. Recent evaluations of health insurance in Vietnam have instead investigated the effects of health insurance expansion on out-of-pocket spending (Jowett, Contoyannis, and Vinh Citation2003; Wagstaff Citation2010; Nguyen Citation2012; Nguyen and Wang Citation2013), healthcare utilization (Wagstaff Citation2007, Citation2010; Nguyen Citation2012; Nguyen and Wang Citation2013; Guindon Citation2014; Palmer et al. Citation2015) and health outcomes (Guindon Citation2014). Two studies specifically assessing HCFP (Wagstaff Citation2007, Citation2010) also fall into this category. However, results from these two studies are relatively sensitive to the methodological choices made, which make one question the robustness of the results presented. For example, Wagstaff (Citation2007) used a single difference and Propensity Score Matching to find that HCFP substantially increased service utilization while in another study using triple differences, the author concluded that HCFP did not change service utilization albeit reducing out-of-pocket payment (Wagstaff Citation2010). Thus, the evidence of the impacts of HCFP on these outcomes is limited and inconclusive, whereas the labour supply effects in particular are under-studied.

III. The Vietnam health care fund for the poor

The expansion of health coverage in Vietnam has recently accelerated owing to improvements in living standards in fast-growing regions as well as the global push for UHC. After the 1986 Reform, normally referred to as ‘Doi Moi’, wherein the economy was shifted from a centrally planned system to a more open and market-oriented economy, the Vietnamese government has conducted a plethora of healthcare reforms (Wagstaff Citation2010) to improve healthcare access and coverage. One illustration is HCFP, which was introduced in 2003 as a subsidized health scheme for the poor and ethnic minority peoples. The aim was to tackle ever increasing out-of-pocket payment, especially for the poor and vulnerable (Wagstaff Citation2010).

HCFP was founded under the Decision 139/2002/QD-TTg (Socialist Republic of Vietnam Citation2002), under which provincial governments are mandated to allocate an annual sum for the Provincial Agency of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs – a subordinate body under Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social affairs (MOLISA) – to buy health insurance cards and then have them delivered to the poor within the province. The budget was allocated annually based on a list of poor people proposed by the agency which gathered information from lower level agencies at district and commune levels via hierarchical reporting. The fund was co-financed by both the central and provincial governments and was introduced to replace a previous programme called Free Health Card (FHC) for the Poor.

According to the Decision, HCFP is to target the poor as defined by MOLISA’s national poverty line issued under Decision 1143/2000/QD-LDTBXH (Socialist Republic of Vietnam Citation2000). However, in practice the specification of poor households at local level was done via community meetings and consultation with local authorities who would then submit an annual list of poor people to provincial authorities. The fund targeted everyone living in the most disadvantaged communes listed under Programme 135 – one of the largest poverty reduction programmes in Vietnam under Decision 135/1998/QD-TTg (Socialist Republic of Vietnam Citation1998) – or those belonging to ethnic minority groups who live in the poorest Central Highland and Northern West provinces.

HCFP pays 100 per cent of the insurance premium for the poor (around 2.5 USD per person per year in 2003) to ensure that every poor person can get free access to any healthcare facility affiliated with the national social health insurance scheme. The Fund then directly pays to service providers upon utilization (according to Decision 139/2002/QD-TTg). This is to ensure that the poor, by law, do not have to pay out-of-pocket in advance. Even though the regulation requires that provincial authorities buy health insurance for the poor, during the implementation process, provincial governments can chose to either (i) buy and issue free health insurance cards for the poor and hence automatically enrol them into the national social health insurance scheme, or (ii) directly reimburse service providers for healthcare services delivered (Tran et al. Citation2011).

In practice, many provincial governments normally use both approaches: (i) issuing health insurance and (ii) providing free healthcare services for the poor irrespective of the availability of health insurance cards (Tran et al. Citation2011). In the latter case, poor certificates, which serve as an identification for the poor, can be used instead when seeking free treatment. Qualitative evidence also shows that some provinces tried to shift the financial burden to the social health insurance system by enrolling sick people into the national insurance scheme while providing user-fee exemption and direct reimbursement to the remaining poor (Tran et al. Citation2011). Therefore, some policy modifications were made in 2005 to remove direct reimbursement and ensure that the poor have health insurance (ibid.). This crucial right was then embraced in subsequent health regulations (i.e. Health Insurance Law versions of 2008 and 2014). However, the flexibility and inconsistency during the early stage of implementation as aforementioned complicates our analysis, as we cannot disentangle the effects of health insurance issued under HCFP and its precedent FHC because the health insurance card could be absent if the poor used poor certificates upon healthcare seeking. Therefore, in this analysis, we decide not to separate the two, which is consistent with previous studies like Wagstaff (Citation2010).

IV. Data and methodology

Data

We use panel data from the Vietnam Household Living Standards Surveys (VHLSS) 2002–2006. VHLSS is a nationally representative multi-purpose household survey in Vietnam, conducted every two years since 2002. It covers many areas including demographics, expenditure, income, health, labour supply, education and so on. This survey originated from the well-known World Banks Living Standards Measurement Surveys (LSMS) and was renamed VHLSS since 2002. Data collection was carried out by Vietnam’s General Statistical Office (GSO) with technical support from the World Bank Vietnam.

All surveys during our study period use the same master sample for sampling, which is extracted from the Vietnamese Population Census 1999. However, they differ in sample size. Importantly, all surveys have two different samples, one larger sample covering all general information and income, and one smaller sample with additional details on expenditure. In each survey, the expenditure component of the household questionnaires is only used for the small sample. As this research uses information on expenditure-based poverty, we use the small samples of all surveys. The small sample sizes in 2002, 2004 and 2006 are respectively more than 30,000, 9,000 and 9,000 households. However, because VHLSS uses a sample rotating approach where only half of the large sample in a previous survey is re-sampled in the next round, this significantly reduces the sample size of the panel.

Importantly, during data crunching we find a large number of matching errors in the panel, which is consistent with what is found by McCaig (Citation2009). The author suggested that around 10 per cent of matches given by GSO’s 2002–2004 official data were imprecise just simply by looking at demographic information such as gender, age and name of the individual (ibid.). The matching errors in VHLSS 2002–2004 panel led to mismatches in the longer panel 2002–2006 that is used in this article. The poorly matched panel creates biased estimates of many household characteristics (e.g. household size, household consumption as illustrated in McCaigCitation2009) and influences estimations on many dynamic issues like labour supply, changes in health status and so on (ibid.). Therefore, in this article, we use the revised household and individual identifiers provided openly on the author’s website (McCaig Citation2017) to correct for the wrong matches.

After data verification and cleaning, we get a panel which includes 6,816 observations in 2002, 7,459 observations in 2004, and 7,441 observations in 2006. We adopt the universally accepted working age definition and only keep individuals aged between 16 and 65 although labour regulations in Vietnam do not set the upper bound.Footnote1 The age cut-offs reduce the sample size to 4,025, 4,723 and 5,095 individuals respectively. We also remove 338 observations who were covered in 2002 under the FHC scheme. The final panel is unbalanced and consists of 3,687, 4,723 and 5,095 observations in 2002, 2004 and 2006.

One important note about the data is that the survey design in 2002 is relatively simplified compared to the other two waves. Questions on health insurance in the 2002 survey are at the household level while information in 2004 and 2006 is for each household member. We hence assume that if a household is covered with HCFP or FHC in 2002, everyone within the family is covered. This assumption is reasonable given the fact that poverty status in Vietnam is specified at household level via community meetings. Another data issue is that the 2002 survey merely asked information on HCFP and its precedent FHC while ignoring other health schemes applicable to the working-age poor (namely health insurance for students, health insurance for social assistance recipients and people of merit: the invalid, the handicapped, mothers of war martyrs). Therefore, in our definition of covered and uncovered groups in 2002, we cannot separate the effect of HCFP from other health insurance schemes for the poor (if any). This issue will be discussed further in Section 7.

Treatment definition and methods

In our definition, covered in 2004 and 2006 is defined as being covered by either HCFP or FHC, and not covered by any other type of health insurance. Covered in 2002 is specified as being covered by either HCFP or FHC, and maybe covered by any other type of health insurance – we simply do not have any information about this. Similarly, uncovered refers to being covered by neither HCFP nor FHC, but maybe covered by other types of health insurance the poor are eligible for. We then define treatment and control groups. In our data, the baseline year is 2002, before the introduction of HCFP in 2003. Treatment include three sub-groups: (i) those covered only in 2006 (group 1), (ii) those covered only in 2004 (group 2) and (iii) those covered in both 2004 and 2006. We bundle these three into one treatment group. Those uncovered in all three years form a pool of potential control individuals for matching techniques.

We combine pre-treatment matching with Difference-in-Differences (DD) to evaluate the effect. Eligibility of health insurance for the poor via HCFP or FHC schemes was not random yet mainly based on poverty status and geographic locations. We therefore use these criteria in our pre-treatment matching to determine a control group before conducting DD estimations.

In our empirical setup, certain assumptions need to be satisfied for the validity of our causal results. Most importantly, the parallel trend assumption must be satisfied. By combing matching with DD, we assume a parallel trend conditional on the matching covariates. Further diagnosis, however, is needed to confirm this parallel trend once the matching is done. Unfortunately, we only have one pre-treatment period, making it impossible to test the trend leading to treatment. Regarding post-treatment trend, in our specification, we allow time-varying treatment effect (see the specifications below), therefore the parallel trend after treatment is relaxed. The choice of matching covariates becomes critically important. We have strong evidence to show that the covariates used for matching are relevant for determining both selection into the programme and labour supply outcomes. We use expenditure-based poverty status,Footnote2 location (urban or rural), and ethnicity – determinants of HCFP eligibility – as mandated by law (Socialist Republic of Vietnam Citation2002) and hence used for implementing the HCFP policy. We also include healthcare utilization as a proxy for the unobserved health status due to evidence that sick and poorer people among the poor might have been prioritised in getting covered (Tran et al. Citation2011). Additionally, self-reported health status is also an important variable in modelling labour supply (Parsons Citation1982). Finally, we include individual and household characteristics that determine labour supply, including age, gender, literacy, marital status, work sector (farm/non-farm), household size, dependency ratio,Footnote3 female headed household (dummy). These determinants of labour supply are defined based on our diagnostic Probit regressions before matching. We also base on labour supply theories, e.g. Heckman and MaCurdy (Citation1980) and empirical evidence (Contreras and Plaza Citation2010; Contreras, De Mello, and Puentes Citation2011; Humphries and Sarasúa Citation2012), to specify these relevant characteristics.

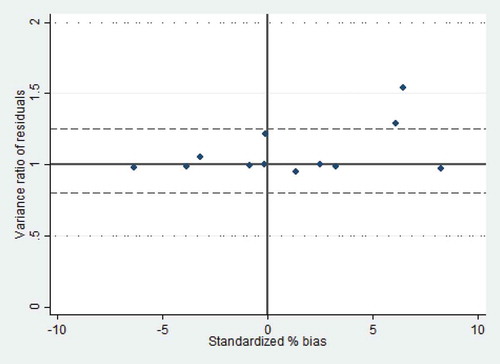

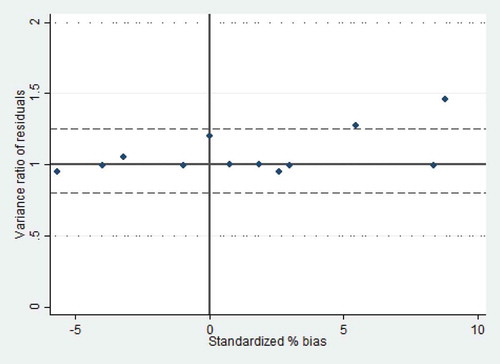

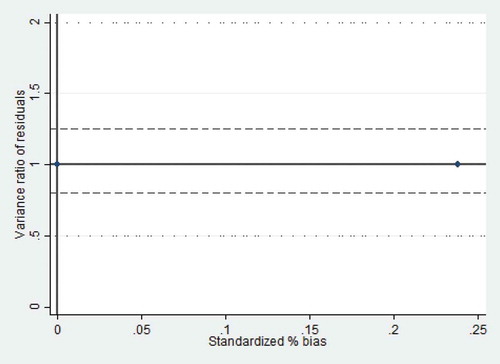

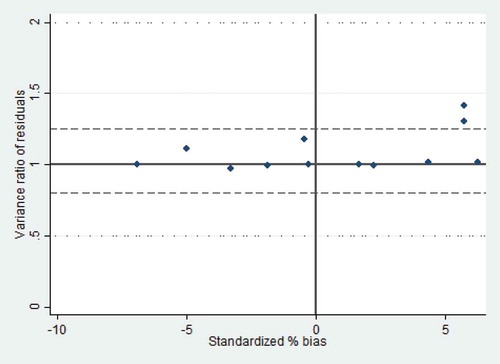

Importantly, due to criticism of and concern about Propensity Score Matching (PSM) methods (see King and Nielsen Citation2016), we deliberately choose Mahalanobis matching over the widely used PSM. However, following the advice by King and Nielsen (Citation2016), we also conduct a number of PSM attempts (including Kernel algorithms, and nearest neighbour matching) and then compare matching results regarding efficiency, and level of bias reduction before switching to the Mahalanobis metric. T-test results are reported in Appendices G-K while Figure A illustrates the variance ratios of disturbance of all matchings.

Based on the diagnostic tests (Appendices G-K) and the disturbance illustrations (Figure A), we conclude that PSM in our case is not an optimal choice due to its inability to completely remove imbalances between the treated and the untreated. Consequently, PSM methods result in a very small number of off-support observations even though we know with certainty that treatment selection bias is an issue because health insurance for the poor was not randomly assigned. This is probably due to, what is explained by King and Nielsen (Citation2016), the blindness of PSM to many imbalances as the method tries to approximate a perfect randomization. We also find that Mahalanobis matching in our case is more efficient by fully removing imbalances and bias between the two groups.

The technique, however, comes with a trade-off: after the Mahalanobis matching, we have to remove from the baseline 402 off-support treated observations which are not compatible with any observation in the potential control group. This number of trimmed observations is relatively large in the total number of 666 treated observations in 2002. Based on the T-Test results, the imbalances mostly come from two household characteristics, that is the household size and whether the household is headed by a female. These two covariates appear to be important determinants of the treatment assignment in our diagnostic regressions. Therefore, we use Mahalanobis matching as the most stringent method. We, however, also use other matching metrics and report the results from all matching techniques.

We use two dependent variables: (i) the number of hours worked per month on average (this is left-censored as only relevant for those being employed) and (ii) the probability of employment as a binary choice. We employ a two-part model for analysing the number of hours worked. Particularly, in the first part, a Probit regression is used to examine the determinants of being employed for all working-age individuals. The second part then uses OLS to examine the effect of the HCFP on the number of hours worked for those who are employed. Regarding labour force participation (dependent variable 2), we use the Linear Probability Model. We use individual fixed effect (the treatment level) to account for unobserved time-invariant characteristics. Because of the high level of discretion of the local authorities in implementing the HCFP (see Tran et al. Citation2011), as well as regional differences in terms of healthcare facilities and inputs, we also control for commune fixed effects. We use clustered standard errors by household for all regressions .Footnote4 The specifications are as follows:

where:

i, c and t respectively denote individual, commune and time subscripts.

‘hour’ denotes the number of hours worked per month on average in Part 2 of the two part model (this regression is only ran on employed individuals).

‘employ’ denotes the probability of being employed for all individuals. ‘employ’

equals 1 if currently employed and equals 0 otherwise.

‘treat’ equals 1 for treated individuals, ‘treat’ equals 0 for the control.

denotes year dummies, t runs from 0 to 2 that respectively denotes 2002, 2004 and 2006.

X’ is the vector of time-variant variables that explain labour supply. X’ also includes the intercept.

is the commune fixed effects.

is the individual fixed effects.

is the idiosyncratic error term.

is the average treatment effect (ATT) of interest.

Time-variant individual and household characteristics in vector X’ consist of age, age squared, literacy, marital status, household size and dependency ratio. Additionally, we proxy for health status by the number of healthcare visits per year. We also account for the effects of labour demand by specifying the geographical regions where the individuals are living using the variable ‘urban’ and the availability of programme 135, one of the largest and most important poverty reduction programmes targeting the poorest communes in Vietnam. We control for the farming sector, which is the most common for the Vietnamese rural poor, and type of work (wage-employment in particular). Finally, because the majority of our sample work in the agriculture sector, we try to control for seasonal effects by adding interview month.

V. Results

Difference-in-Differences Matching estimates for the number of hours worked are presented in . Part 1 of the two part model is presented in Appendix B.

Table 1. Part 2 – The number of hours worked – OLS.

As suggested in , the HCFP has a negative effect on the number of hours worked. On monthly average, those covered with free health insurance via the HCFP work around 5.2–5.8 hours less compared to those uncovered by the scheme. This finding is consistent across different matching techniques. Besides, the negative effect is more prominent in 2004 than in 2006, suggesting that the negative effect (probably due to the income effect) kicks in rather quickly.

The effects of control variables are very consistent and intuitive. Age has a concave relationship with the number of hours worked. Seeking more healthcare is associated with working less. Notably, the effect of work sector is rather large: those working in the agricultural sector, on average, work approximately 40 hours less than those working in the non-farm sector. This large effect indicates that the HCFP may have the largest effects on those working in agriculture.

presents Difference-in-Differences Matching estimates of the second outcome: the probability of employment. As suggested, the HCFP has a negative effect on labour force participation. On average, those covered with free health insurance during HCFP are 2.8 percentage points less likely to participate in the labour market. This result is very consistent across different matching methods. This effect does not change over time as the effects of the time dummies are statistically insignificant.

Table 2. Probability of being employed – Linear probability model.

The effects of other control variables on labour force participation are rather intuitive. Similar to the effect on the number of hours worked, age has a concave relationship with labour force participation. Interestingly, those living in a family with more dependants are less likely to participate in the labour market probably due to the care burden at home. Literate people are 7.5–7.7 percentage points more likely to get employed. Those who are not married are more likely to work. Seeking more healthcare is associated with a smaller likelihood of labour force participation. Those working in agriculture are 25 percentage points more likely to participate in the labour market. Those working in a salary job (compared to self-employment) are approximately 21 percentage points more likely to work.

Because the employment structure and type of work are significantly different in rural and urban areas, we also break down the results by region. Additionally, as the treated individuals in our sample also include the non-poor (see Table A) while the income effect might be significantly different for individuals of different levels of initial income, it is important to distinguish the effect for the poor and the non-poor to evaluate the effects on the target group of interest. These effects by region and by poverty status are presented in and . As the results are consistent across different matching methods in and , we only report the broken-down results of Mahalanobis matching in and

Table 3. The number of hours worked per month, by poverty status and by region.

Table 4. The probability of employment, by poverty status and by region.

According to , the HCFP effects on the number of hours worked are more evidenced for the non-poor treated individuals while being statistically insignificant for the poor. This surprising result indicates that the income effect of HCFP is more relevant for the non-poor than the poor. On average, the treated non-poor are working 5.6 hours less than the non-poor control individuals and this effect is significant at five percent level. In contrast, for the poor, the effect is statistically insignificant. also suggests that the negative effect of health insurance is mainly driven by rural individuals. Approximately, rural treated individuals work 8.3 hours less than rural control individual and this effect is significant at one percent level. The effect for the urban individuals is, however, statistically insignificant. According to , there is no difference in the HCFP effect on labour force participation between the poor and the non-poor. The effect, however, is more evident for rural individuals: the HCFP make treated individuals in rural areas 3.8 percentage points less likely to get employed compared to the rural control individuals.

VI. Discussion

We find evidence of negative effects of HCFP on labour supply both at the intensive and extensive margins (i.e. the number of hours worked and labour force participation). The negative effect of the HCFP found in this article indicates that the income effect dominates health-fostering effect in labour supply decisions. Importantly, the HCFP effect at the intensive margin (i.e. the number of hours worked) changes over time. Particularly, the income effect immediately kicked in after the launch of the HCFP (in 2004) while the time dummy for 2006 is not statistically significant. This means that the negative HCFP effect on the number of hours worked is stronger for those covered in 2004 than those covered in 2006 (this group also included those covered in both years).

Our finding of the negative effects both at intensive and extensive margins of labour supply is interesting given the very small health insurance premium subsidized (around 2.5 USD in 2003, equivalent of approximately 1/40 of the annual poverty line in 2003) as well as the low cost of public healthcare services in Vietnam. One may have argued that the income increase relative to the total income of those treated non-poor individuals is not large enough to trigger the income effect from the first year of implementation. However, it is important to note that out-of-pocket payments in Vietnam in 2003 were very high, at around 63 per cent of total health spending (World Bank Citation2018). Therefore, the income effect in the form of reduced health expenses are large enough to trigger the negative labour supply effects.

Importantly, we find that the effect on the number of hours worked is mainly driven by the non-poor, especially those living in rural areas (see ). These include non-poor ethnic minority peoples living in disadvantaged areas and hence qualifying the categorical targeting criteria. They can also be the near-poor who were not poor based on the World Bank expenditure based poverty line but were defined as poor by the local community. Or they were mistakenly covered due to lots of other implementation complications – this comprises the real inclusion error of the programme. Meanwhile, in Vietnam the poor in rural regions often comprise ethnic minority individuals living in remote and disadvantaged areas where health access and health literacy are limited (Nguyen Citation2010), and that it often takes some time to raise their awareness of public programmes. Therefore, during the first stage of HCFP wherein direct reimbursement was conducted in many provinces, the programme might not be able to benefit the poorest of the poor probably due to their lower take-up rate (caused by lack of knowledge and limited accessibility) and lower healthcare utilization compared to the non-poor who normally live closer to local healthcare centres. Unfortunately, information regarding distance to the nearest healthcare delivery points was not asked in all three data periods so we could not test this hypothesis. Additionally, other studies that looked at utilization and out-of-pocket payment of this specific programme (Wagstaff Citation2010, Citation2007) only examined the average treatment effect for those covered and did not delve deeper into this poverty angle, so it is difficult to justify this extrapolation.

Most of the existing literature only evaluated the short-term effect – normally right after an intervention. In this article, we have taken advantage of the three-wave panel and examined the effects one year and three years after the intervention. We find that the treatment effect on the number of hours worked changes over time: it kicks in quickly after the intervention but then loses its effect over time.

It is difficult to compare our results with the existing literature due to the over-representation of studies on the U.S. healthcare system as well as the inconclusiveness of the empirical evidence (see the systematic review by Lê et al. Citation2019). We have evidence of Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Programme (CHIP) and Affordable Care Act in the United States but the evidence of these studies is rather mixed with different target groups of low-income beneficiaries (ibid.). Our estimates regarding the effect on the number of hours worked are smaller in size compared to an effect size of six hours per week (or on average 24 hours per month) suggested by Rosen (Citation2014) for Medicaid recipients. This might reflect the larger generosity, and hence bigger income effect, of the Medicaid programme compared to the HCFP in Vietnam. Regarding labour force participation, the results in the literature are rather mixed. Our results are contrary to findings by Strumpf (Citation2011) and Ham and Shore-Sheppard (Citation2005) who suggested that the introduction and expansion of Medicaid did not affect the likelihood of labour force participation. In another randomized experiment on Medicaid by Baicker et al. (Citation2014), the authors also found no significant effect on employment.Footnote5 In contrast, our results are consistent with other studies that found that low-income childless adults reduced their employment likelihood due to the Affordable Care Act (Guy, Atherly, and Kathleen Adams Citation2012) and a state-level health insurance expansion in Wisconsin, U.S. (Dague, DeLeire, and Leininger Citation2017).

The finding of a negative net effect of the HCFP on the number of hours worked for the non-poor raises concern in the context of moving towards UHC in Vietnam. The key question for policy makers would be how to better target the poor to ensure equity while avoiding unintended labour supply distortions.

This study comes with a data limitation caveat. Effects of health insurance subsidies other than the HCFP cannot be adequately accounted for due to data limitations in 2002. The health section of 2002’s questionnaire does not include any question on health coverage. The information on HCFP and FHC is however asked at the household level in another section on public subsidies and assistance benefits. This is inconsistent with the design of the later surveys in 2004 and 2006, where different types of health insurance are specified for each household member (and hence the level of analysis is at individual level). This data limitation leads us to assume HCFP coverage for the whole family if a household answered that at least one person within the family received this health scheme in 2002. Additionally, due to not being asked, the coverage of other types of health insurance in 2002 is unknown, potentially leading to an under-or-over estimation of the effect magnitude depending how these health insurances are distributed among treatment and control groups in 2002. However, this data unavailability does not bias our estimates if we assume that conditional on the matching observables, the distribution of other types of health insurance between the treatment and control groups in 2002 are compatible. In this case, the bias caused by other types of health insurance in 2002 would be cancelled out in the pre-treatment difference (in mathematical terms, it equates treatment minus control in the baseline).

VII. Conclusion

By using matching methods combined with Difference-in-Differences, we evaluated the labour supply effects of free health insurance coverage under the HCFP for the benefit recipients in Vietnam. We examined labour supply responses at both intensive and extensive margins: the number of hours worked and employment likelihood (labour force participation). We found that the effects of free health insurance on the number of hours worked and labour force participation were both negative and statistically significant at five percent level. Importantly, the effects were mainly driven by the non-poor people living in rural areas. This raises the question of the targeting strategy of the programme, highlights the importance of infrastructure availability as well as awareness raising and improving health literacy for the poor when designing such public health schemes.

We contribute to the existing literature in several ways. First, we help fill the knowledge gap for LMIC where health insurance coverage is rapidly expanding yet unguided by empirical evidence on labour market effects. Second, we analyse the labour supply effects over a longer time span after the intervention. This allows us to capture the time change of the income effect induced by health insurance. Third, we dig deeper into the poverty perspective to unravel the mechanisms behind labour market distortions of health insurance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 According to Vietnam’s labour law in 1992 and its amendment in 2004, legal workers are those who are above 15.

2 We use poverty line (Glewwe Citation2003) in 2002 to identify who were poor in the baseline year 2002.

3 This is defined as the total number of dependants aged below 16 or above 65 over the total household size.

4 We assume that the residual of work hours is likely to correlated within household and report household clustered standard errors in the main results. However, we also run clustered error by commune to test if the residual is correlated within local labour markets. The results are reported in the Appendices.

5 The authors used the information about whether or not an individual has an earning as a measure for employment.

References

- Baicker, K., A. Finkelstein, J. Song, and S. Taubman. 2014. “The Impact of Medicaid on Labor Market Activity and Program Participation: Evidence from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment.” American Economic Review 104 (5): 322–328.

- Banerjee, A. V., R. Hanna, G. E. Kreindler, and B. A. Olken. 2017. “Debunking the Stereotype of the Lazy Welfare Recipient: Evidence from Cash Transfer Programs.” The World Bank Research Observer 32 (2): 155–184.

- Boyle, M. A., and J. N. Lahey. 2010. “Health Insurance and the Labor Supply Decisions of Older Workers: Evidence from a US Department of Veterans Affairs Expansion.” Journal of Public Economics 94 (7): 467–478.

- Chou, S.-Y., J.-T. Liu, and J. K. Hammitt. 2002. “Health Insurance and Households’ Precautionary Behaviors-An Unusual Natural Experiment.” NBER Working Paper No. 9394 NBER Working Paper No. 9394. http://www.nber.org/papers/w9394

- Chou, Y.-J., and D. Staiger. 2001. “Health Insurance and Female Labor Supply in Taiwan.” Journal of Health Economics 20 (2): 187–211.

- Contreras, D., and G. Plaza. 2010. “Cultural Factors in Women’s Labor Force Participation in Chile.” Feminist Economics 16 (2): 27–46.

- Contreras, D., L. De Mello, and E. Puentes. 2011. “The Determinants of Labour Force Participation and Employment in Chile.” Applied Economics 43 (21): 2765–2776.

- Nguyen, V. C. 2010. “Public Health Services and Health Care Utilization in Vietnam.” Munich Personal RePEc Archive 33610. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/33610

- Dague, L., T. DeLeire, and L. Leininger. 2017. “The Effect of Public Insurance Coverage for Childless Adults on Labor Supply.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9 (2): 124–154.

- Dave, D., S. L. Decker, R. Kaestner, and K. I. Simon. 2015. “The Effect of Medicaid Expansions in the Late 1980s and Early 1990s on the Labor Supply of Pregnant Women.” American Journal of Health Economics 1 (2): 165–193.

- Glewwe, P. 2003. “Procedure for Calculating Nominal and Real Expenditures, and Poverty Indicators, for the 2002 VHLSS.” http://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/2306/download/34491

- Gooptu, A., A. S. Moriya, K. I. Simon, and B. D. Sommers. 2016. “Medicaid Expansion Did Not Result in Significant Employment Changes or Job Reductions in 2014.” Health Affairs 35 (1): 111–118.

- Gruber, J. 2010. Public Finance and Public Policy. 3rd ed. New York: Macmillan.

- Gruber, J., and B. C. Madrian. 2002. “Health Insurance, Labor Supply, and Job Mobility: A Critical Review of the Literature.” NBER Working Paper No. 8817. http://www.nber.org/papers/w8817

- Guindon, G. E. 2014. “The Impact of Health Insurance on Health Services Utilization and Health Outcomes in Vietnam.” Health Economics, Policy and Law 9 (4): 359–382.

- Guy, G. P., A. Atherly, and E. Kathleen Adams. 2012. “Public Health Insurance Eligibility and Labor Force Participation of Low-Income Childless Adults.” Medical Care Research and Review 69 (6): 645–662.

- Ham, J. C., and L. D. Shore-Sheppard. 2005. “Did Expanding Medicaid Affect Welfare Participation?” ILR Review 58 (3): 452–470.

- Heckman, J. J., and T. E. MaCurdy. 1980. “A Life Cycle Model of Female Labour Supply.” The Review of Economic Studies 47 (1): 47–74.

- Humphries, J., and C. Sarasúa. 2012. “Off the Record: Reconstructing Women’s Labor Force Participation in the European Past.” Feminist Economics 18 (4): 39–67.

- Jowett, M., P. Contoyannis, and N. D. Vinh. 2003. “The Impact of Public Voluntary Health Insurance on Private Health Expenditures in Vietnam.” Social Science & Medicine 56 (2): 333–342.

- King, G., and R. Nielsen. 2016. “Why Propensity Scores Should Not Be Used for Matching.” Harvard working paper series. http://j.mp/2ovYGsW

- Lê, N., W. Groot, S. M. Tomini, and F. Tomini. 2019. “Effects of Health Insurance on Labour Supply: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Manpower. http://www.merit.unu.edu/publications/wppdf/2017/wp2017-017.pdf

- Le, N., Groot, W., Tomini, S. M., Tomini, F. 2019. “Effects of health insurance on labour supply: a systematic review”, International Journal of Manpower, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-02-2018-0038

- Lagomarsino, G., A. Garabrant, A. Adyas, R. Muga, and N. Otoo. 2012. “Moving Towards Universal Health Coverage: Health Insurance Reforms in Nine Developing Countries in Africa and Asia.” The Lancet 380 (9845): 933–943.

- Levy, H., and D. Meltzer. 2004. “What Do We Really Know about whether Health Insurance Affects Health.” In Health Policy and the Uninsured, edited by C. G. McLaughlin, 179–204. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press

- McCaig, B. 2009. “The Reliability of Matches in the 2002-2004 Vietnam Household Living Standards Survey Panel.” Discussion paper. Centre for Economic Policy Research, Australian National University. https://www.rse.anu.edu.au/media/604599/dp622.pdf

- McCaig, B. 2017. “Note on VHLSS.” Data retrieved from Brian McCaig’s website. https://sites.google.com/site/briandmccaig/home/notes-on-vhlsss

- Nguyen, V. C. 2010. “Public Health Services and Health Care Utilization in Vietnam.” Munich Personal RePEc Archive 33610. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/33610

- Nguyen, C. V. 2012. “The Impact of Voluntary Health Insurance on Health Care Utilization and Out-Of-Pocket Payments: New Evidence for Vietnam.” Health Economics 21 (8): 946–966.

- Nguyen, H., and W. Wang. 2013. “The Effects of Free Government Health Insurance among Small Childrenevidence from the Free Care for Children under Six Policy in Vietnam.” The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 28 (1): 3–15.

- Palmer, M., S. Mitra, D. Mont, and N. Groce. 2015. “The Impact of Health Insurance for Children under Age 6 in Vietnam: A Regression Discontinuity Approach.” Social Science & Medicine 145: 217–226.

- Parsons, D. O. 1982. “The Male Labour Force Participation Decision: Health, Reported Health, and Economic Incentives.” Economica 49 (193): 81–91.

- Rodin, J., and D. de Ferranti. 2012. “Universal Health Coverage: The Third Global Health Transition?” The Lancet 380 (9845): 861.

- Rosen, G. 2014. “Determinants of Employment: Impact of Medicaid and CHIP among Unmarried Female Heads of Household with Young Children.” Social Work in Public Health 29 (5): 491–502.

- Socialist Republic of Vietnam. 1998. Decision 135/1998/Qd-Ttg on Socio-Economic Development Plan for the Most Difficulty Communes in Mountainous Areas and Isolated Regions. Hanoi, Vietnam: Vietnamese Government Office.

- Socialist Republic of Vietnam. 2000. Decision 1143/2000/QD-LDTBXH on Poverty Line during 2001-2005. Hanoi, Vietnam: Ministry of Labour, the Invalids and Social Affairs of Vietnam.

- Socialist Republic of Vietnam. 2002. Decision 139/2002/Qd-Ttg on Healthcare for the Poor. Hanoi, Vietnam: Vietnamese Government Office.

- Socialist Republic of Vietnam. 2016. Decision 1167/Q-Ttg on Target Adjustments for Expanding Health Insurance Coverage in Vietnam during 2016-2020. Hanoi, Vietnam: Vietnamese Government Office.

- Sommers, B. D., K. Baicker, and A. M. Epstein. 2012. “Mortality and Access to Care among Adults after State Medicaid Expansions.” New England Journal of Medicine 367 (11): 1025–1034.

- Strumpf, E. 2011. “Medicaid’s Effect on Single Women’s Labor Supply: Evidence from the Introduction of Medicaid.” Journal of Health Economics 30 (3): 531–548.

- Tran, V., T. Tien, P. Hoang, I. Mathauer, and T. K. P. Nguyen. 2011. Health Financing Review of Vietnam with a Focus on Social Health Insurance: Bottlenecks in Institutional Design and Organizational Practice of Health Financing and Options to Accelerate Progress Towards Universal Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organisation. http://www.who.int/healthfinancing/documents/oasisf11−vietnam.pdf

- Wagstaff, A. 2007. “Health Insurance for the Poor: Initial Impacts of Vietnam’s Health Care Fund for the Poor.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4134. https://ssrn.com/abstract=961760

- Wagstaff, A. 2010. “Estimating Health Insurance Impacts under Unobserved Heterogeneity: The Case of Vietnam’s Health Care Fund for the Poor.” Health Economics 19 (2): 189–208.

- Wagstaff, A., and R. Moreno-Serra. 2009. “Europe and Central Asia’s Great Post- Communist Social Health Insurance Experiment: Aggregate Impacts on Health Sector Outcomes.” Journal of Health Economics 28 (2): 322–340.

- Wagstaff, A., and R. Moreno-Serra. 2015. “Social Health Insurance and Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from Central and Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, 83–106.” Emerald Insight. http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/S0731-2199

- World Bank. 2018. Country Data of Vietnam. Accessed September 5, 2018. https://data.worldbank.org/country/vietnam

Appendix A.

HCFP and FHC coverage (%)

Coverage of HCFP or its precedent during 2002–2006 is presented in Appendix A. As suggested, coverage increased over time during 2002–2006. Those who were covered in 2002 were the beneficiaries of FHC policy which was then replaced by HCFP in late 2002 and 2003. The introduction of HCFP indeed has contributed to raising the coverage for eligible people, from nearly 17 per cent in 2002 to around 34 and 50 per cent in 2004 and 2006 respectively.

Inclusion error was another issue as more than 11 per cent of those ineligible in 2006 got coverage. Moreover, exclusion error was high, probably due to budget constraints as in 2006 only half of the eligible poor population were covered. Our findings of inclusion and exclusion errors are consistent with other estimates of HCFP coverage and leakage (see Wagstaff Citation2010).

Appendix B.

Part 1 – Probit model – Probability of being employed (all individuals)

Table

Appendix C.

Part 2 – The number of hours worked – OLS (with commune clustered standard errors)

Table

Appendix D.

Probability of being employed – Linear Probability Model (with commune clustered standard errors)

Table

Appendix E.

The number of hours worked per month, by poverty status and by region (with commune clustered standard errors)

Table

Appendix F.

The probability of employment, by poverty status and by region (with commune clustered standard errors)

Table

Appendix G.

Matching results

As illustrated, Mahalanobis matching in this case manages to fully remove bias between the treated and untreated observations (see the results in bold). In contrast, PSM methods fail to fully clean up the imbalances between the two groups and suggest a very small number of off-support observations. This leads us to doubt the quality of PSM metrics which try to approximate a completely randomized sample and potentially ignore many imbalances. Similarly, figures of disturbance variance after matching suggest the use of Mahalanobis matching.