?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper examines the effects of main bank switching on the probability of bankruptcy of new small businesses using a propensity score matching estimation approach. We use a unique firm-level dataset of approximately 1,000 small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) incorporated in Japan; these SMEs are young and unlisted just after incorporation. We find that switching main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy. In addition, the result holds only when the relationship between the firm and its main bank is terminated. Specifically, the probability of bankruptcy increases when firms switch their main banks to financial institutions with which they have not previously transacted, and when the ex-post main banks are not affiliated financial institutions of their ex-ante main banks. These results may be because such switching worsens the financial condition of client firms, and thus, it leads to bankruptcy.

I. Introduction

For small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), firm–bank relationships are important because such firms largely depend on indirect financing. Thus, numerous studies in banking have examined how the continuation of firm–bank relationships affects lending terms and conditions (e.g. Petersen and Rajan Citation1994; Berger and Udell Citation1995; Cole Citation1998; Degryse and Cayseele Citation2000; Brick and Palia Citation2007; Ono and Uesugi Citation2009). In this strand of literature, some studies argue that relationship lending leads to a flexible supply of funds to firms in financial distress and serves as insurance against a temporary shortage of liquidity (e.g. Chemmanur and Fulghieri Citation1994; Berlin and Mester Citation1998). In addition, other studies suggest that banks play important roles in preventing the bankruptcy of client firms (e.g. Mayer Citation1988; Hoshi, Kashyap, and Scharfstein Citation1990; Grunert and Weber Citation2009; Shimizu Citation2012; Ogane Citation2016). Hence, based on these studies, the continuation of firm–bank relationships may improve business performance, and thus, may reduce the bankruptcy of SMEs.

Since Altman (Citation1968), which is the first study to investigate the impact of financial intermediation on firm bankruptcy, numerous studies have examined this issue. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has empirically investigated the effects of termination of firm–main bank relationships on the bankruptcy of young and unlisted SMEs. Examining such effects is important owing to the following reasons. First, several studies show that the smaller and younger firms are, they are more likely to switch their main banks (e.g. Ongena and Smith Citation2001; Kano Citation2007). In addition, Farinha and Santos (Citation2002) find that the estimated median duration for firms to switch from single to multiple bank lending relationships is approximately five years. Moreover, Uchida, Udell, and Watanabe (Citation2008) argue that young firms have weaker relationships with their main banks than mature firms. These studies suggest that firm–bank relationships for young firms are unstable, and thus, such firms switch their main banks more easily than mature firms.

From another point of view, these previous studies suggest that the termination of firm–bank relationships increases the probability of bankruptcy of client firms. In particular, the impact of such termination on the bankruptcy of young and unlisted SMEs is considered significant because these firms are the most vulnerable among all enterprises. For example, Mata (Citation1994) argues that firms are most likely to go bankrupt within a few years of incorporation. In addition, the 2006 White Paper on Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan reports that the first 5- and 10-year survival rates of start-up companies in Japan are 41.8% and 26.1%, respectively. In contrast, it also reports that mature firms seldom go bankrupt.Footnote1 Moreover, unlisted SMEs cannot raise funds through direct finance, and thus, they also tend to go bankrupt. In summary, young and unlisted SMEs are likely to switch their main banks and to go bankrupt.Footnote2 Considering these reasons, it is important to investigate the causal relationship between switching firm–main bank relationships and the bankruptcy of young and unlisted SMEs.

Against this background, this paper is the first to empirically examine the effects of switching firm–main bank relationships on the probability of bankruptcy of young and unlisted SMEs. To deal with sample selection bias, we employ a propensity score matching estimation approach. Moreover, we divide switching firm–main bank relationships into ‘transfer’ and ‘new transaction.’ In the former case, firms switch their main banks to other financial institutions with which they have transacted before. Thus, in this case, the firm–main bank relationships continue. In contrast, in the latter case, we cannot confirm whether firms switch them to different main banks with which they have previously transacted. Hence, this switching is accompanied by termination of the relationship.

The major findings of this paper are as follows. We find that switching firm–main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy. In addition, this probability increases only when the switching is a ‘new transaction,’ as mentioned. This result may be because such switching worsens the financial condition of client firms. We also find that the result holds only when the ex-post main banks are not affiliated financial institutions of their ex-ante main banks. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the economic impact of exogenous switching for client firms is larger than that of switching in general.

The most significant contribution of this study is that it addresses one of the most important open questions in recent research on banking; that is, whether switching firm–bank relationships affects firm bankruptcy. For example, Fukuda, Kasuya, and Akashi (Citation2009) show that bank health affects the default risk of small firms, suggesting that firm–bank relationships affect the bankruptcy of small businesses. In addition, numerous studies on relationship lending that have examined the effects of firm–bank relationships on lending terms and conditions (e.g. Petersen and Rajan Citation1994; Berger and Udell Citation1995; Cole Citation1998; Degryse and Cayseele Citation2000; Ono and Uesugi Citation2009) also imply that such switching affects firm bankruptcy. However, these studies do not directly investigate the effects of this switching on bankruptcy. In contrast, we employ an original dataset and classification method for switching firm–main bank relationships (i.e. ‘transfer,’ ‘new transaction,’ ‘in a narrow sense,’ and ‘in a broad sense’), and examine the effects of such switching on the probability of firm bankruptcy, while considering its relationship with the theory of relationship lending.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews previous literature. Section 3 develops our empirical hypotheses. Section 4 explains our dataset. Section 5 presents the empirical methodology and results. Section 6 conducts further analyses. Section 7 concludes the paper.

II. Literature review

This paper is closely related to the following three strands of literature.

First, we review the literature on switching firm–bank relationships and establishing new banking relationships. Ongena and Smith (Citation2001) empirically examine the duration of firm–bank relationships using hazard models; they show that firms are more likely to switch main banks as the duration of the relationship becomes longer.Footnote3 This result suggests that banking transactions are not susceptible to the lock-in effect. In addition, Ioannidou and Ongena (Citation2010) find that banks offer lower interest rates to firms when establishing new banking relationships. Furthermore, Gopalan, Udell, and Yerramilli (Citation2011) argue that small public firms that do not transact with larger banks are more likely to build new banking relationships.

Second, we review the literature on how firm–main bank relationships affect business performance, particularly in Japanese cases.Footnote4 These studies mainly target large and listed companies and often regard firms that are members of corporate groups (keiretsu) as having main banks.Footnote5 Some studies argue that there is no evidence that firm–main bank relationships improve corporate performance. For example, Prowse (Citation1992) shows that there is no significant difference in net profits between keiretsu members and independent firms. In addition, Kang and Shivdasani (Citation1999) argue that the operating profits of independent firms are larger than those of firms with group affiliations. Moreover, Weinstein and Yafeh (Citation1998) do not find evidence that main bank relationships affect firm growth; however, they find that such relationships decrease firm profitability. Furthermore, Hanazaki and Horiuchi (Citation2000) show that there is no evidence that stable firm–main bank relationships affected the total factor productivity (TFP) of firms in 1980 or earlier; however, they show that such relationships significantly reduced TFP between 1981 and 1990. In contrast, Lichtenberg and Pushner (Citation1994) obtain the opposite result, that is, main bank relationships improve corporate performance. They examine the relationship between TFP and financial institution shareholding, using data on listed manufacturing firms, and find that equity ownership by financial institutions increases firm productivity.

Third, this paper is closely related to the literature on how firm–main bank relationships affect firm performance. However, few studies have examined the effects of the continuation of such relationships on business performance of SMEs. Hori (Citation2005) examines the effects of the Hokkaido Takushoku Bank failure on the ex-post profitability of the bank’s client firms but does not find evidence that the bank’s failure significantly affected the profitability of client firms. In addition, Fukuda and Koibuchi (Citation2007) analyse the effects of bank failures on the customers of two large failed Japanese banks (i.e. the Long-term Credit Bank of Japan and the Nippon Credit Bank) and show that the profits of small firms decrease when firm–bank relationships are terminated. Moreover, Gambini and Zazzaro (Citation2013) find a negative correlation between long-lasting relationship lending and firm growth, using a sample of Italian manufacturing firms. Furthermore, Tsuruta (Citation2014) argues that ex-post firm performance improves after firms with distressed main banks switch their main bank relationships. Except for Fukuda and Koibuchi (Citation2007) and Gambini and Zazzaro (Citation2013), these studies employ samples of large and listed companies.Footnote6

III. Empirical hypotheses

Most previous studies on relationship lending focus on firm–main bank relationships and find that continuous relationships improve lending terms and conditions (e.g. Petersen and Rajan Citation1994; Berger and Udell Citation1995; Cole Citation1998; Harhoff and Körting Citation1998; Berger, Rosen, and Udell Citation2007). These studies suggest that switching prevents firms from obtaining long-term borrowing. In Japan, dependence on short-term borrowing increases the risk of firm bankruptcy because bankruptcies occur when firms cannot repay short-term borrowing by the repayment date.Footnote7 In contrast, the late payment of long-term borrowing does not immediately lead to bankruptcy. Hence, firms prefer long-term borrowing to short-term; however, financial institutions prefer short-term lending because they would like to recover their loans as soon as possible. Therefore, to obtain long-term borrowing, firms must acquire good reputations from their financial institutions. In particular, financially opaque firms must gain the trust of such financial institutions through repeated repayments. In other words, these firms cannot obtain long-term borrowing without continuous firm–bank relationships.

Next, we explain why continuous firm–main bank relationships enable financially opaque firms to obtain long-term borrowing. Financial institutions must collect information about these firms when providing financing. The information that the financial institutions gather is soft information, which is not easily quantified and contains data gathered over time through contact with the firms (Uchida, Udell, and Yamori Citation2012). If financial institutions can produce good (positive) soft information about a firm’s quality, it mitigates problems stemming from asymmetric information. As a result, this increases the firm’s credit availability (Diamond Citation1991; Boot and Thakor Citation1994; Petersen and Rajan Citation1994; Berger and Udell Citation1995; Boot Citation2000). These studies suggest that financial institutions attempt to maintain the relationship as long as possible after obtaining good (positive) soft information. In other words, financial institutions come to provide long-term lending to the firms. However, in contrast to hard information, it takes a long time for loan officers to collect soft information about borrowers, and thus, firms cannot obtain long-term borrowing from financial institutions without continuous relationships.

Here, we consider the choice of loan maturity. The discussion on the maturity choice is important because we cannot employ long-term borrowing as a proxy for long firm–bank relationship without considering borrowers’ creditworthiness. Diamond (Citation1991) theoretically shows that borrowers with high creditworthiness prefer short-term borrowing because they are confident that they will be able to refinance at better lending terms and conditions in future.Footnote8 Thus, long-term borrowing would not be a proxy for long firm–bank relationship when client firms are creditworthy. In contrast, the situation differs when firms are less creditworthy. More specifically, these firms prefer long-term borrowing to avoid failure to refinance. In providing financing to financially opaque SMEs, financial institutions generally have the right to choose maturity because they have stronger bargaining power than these SMEs.Footnote9 The sample firms in this paper are young and unlisted SMEs, which are unlikely to have much bargaining power; thus, we can assume that without continuous relationships, the sample firms can only choose short-term borrowing.Footnote10 In contrast, as Diamond (Citation1989) suggests, these firms can obtain long-term loans after establishing reputation with the financial institutions. Hence, in this paper, long-term borrowing is likely to be a proxy for long-term firm–bank relationship.

In summary, the firms in this paper cannot obtain long-term borrowing without continuous relationships; in other words, switching firm–main bank relationships prevents them from obtaining long-term borrowing. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, dependence on short-term borrowing increases the risk of bankruptcy. Hence, we posit Hypothesis 1:

Hypothesis 1:

Switching firm–main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy.

Switching prevents firms from obtaining long-term borrowing because financial institutions are unable to accumulate soft information about client firms. However, the probability of bankruptcy should never increase when firms switch their main banks to financial institutions that have soft information about the firms. In other words, the probability of bankruptcy is unlikely to increase when firms switch them to financial institutions with which they have transacted before switching. This is because most prior studies on relationship lending suggest that financial institutions other than main banks also collect soft information about firms as far as they have contact with such firms. In this case, switching is not accompanied by the termination of ex-ante firm–bank relationships, and thus, it does not prevent firms from obtaining long-term borrowing. As a result, the probability of bankruptcy does not increase. Therefore, our second hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 2:

Hypothesis 1 is supported only when a firm switches its main banking relationship to a financial institution with which the firm has not transacted before switching.

In at least two cases, firm–bank relationships are not terminated even if client firms switch main banks. First, if a firm switches to a financial institution with which it has transacted before, such switching is not accompanied by termination. In this case, we can expect that the ex-post main bank already possesses soft information about the client firm before switching; thus, the firm can obtain long-term borrowing from the ex-post main bank comparatively early, even if it switches its main bank. Therefore, this type of switching (i.e. ‘transfer’) does not increase the probability of bankruptcy.

Second, the termination of firm–bank relationships also does not occur when a firm switches to a financial institution affiliated to its ex-ante main bank. For example, a firm switches its main bank due to the merger of its ex-ante main bank. In this case, the firm has transacted with its ex-post main bank before switching, and thus, this type of switching (e.g. ‘switching in the broad sense’) does not increase the probability of bankruptcy.

In summary, our hypotheses posit that switching firm–main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy only when firms switch their main banks to financial institutions with which the firms have not transacted before switching.Footnote11

IV. Data

We construct a unique firm-level dataset from the following sources. First, we employ the firm-level database provided by Tokyo Shoko Research, Ltd. (TSR), one of the largest credit reporting agencies in Japan. This dataset comprises three types of files: the TSR Enterprise Information File, the TSR Bankrupt Information File, and the TSR Stand-Alone Financial Information File. Our original sample contains firms incorporated in Japan between April 2003 and June 2008, as unlisted companies with start-up capital less than 50 million yen.Footnote12 This dataset comprises 887 continuing firms and 121 bankrupt firms. Moreover, the dataset only includes information on the first settlement of accounts. These 1,008 firms represent almost all firms that meet the above data extraction conditions in the TSR database.

Moreover, we use the following aggregate data for each prefecture: Nihon Kinyu Meikan (directory of Japanese financial institutions) published by Nihon Kinyu Tsushin Sha, the Number of Prefectural Sorted Ordinary Corporation published by the National Tax Agency, and Orbis provided by Bureau van Dijk.

Sample selection

As previously mentioned, we focus on young and unlisted SMEs because despite their importance, few studies focus on the relationships between young firms and their financial institutions. However, there may be some disadvantages from focusing on these firms. One possible disadvantage is that it could create bias. Specifically, firm–bank relationships generally grow stronger as they continue, and thus, using data of young SMEs might lead to a bias towards rejecting our hypotheses in the estimation results. Therefore, using data of all SMEs would be more appropriate for observing the effects of firm–main bank relationships on firm bankruptcy.

We acknowledge the above disadvantages but the bias would not be a serious problem in concluding that firm–main bank relationships are important in reducing the probability of firm bankruptcy. This is because Ogura (Citation2012) finds that continuing firm–bank relationships enhance credit availability for new firms as well as other SMEs. This result suggests that these relationships are important for improving credit availability even for young firms. Thus, unsurprisingly, firm–main bank relationships are still important in reducing the probability of firm bankruptcy, even for young SMEs whose firm–bank relationships are considered weak.

Switching main bank relationships

Following widely accepted convention, we define a main bank as the financial institution at the head of the bank name list in the TSR Enterprise Information File.Footnote13 In this file, financial institutions are generally arranged in descending order of their loan amounts. Hence, in this paper, the main bank is almost the same as the financial institution with the largest amount of lending of a firm’s correspondent financial institutions. In addition, we judge switching firm–main bank relationships by checking whether we can confirm that such switching occurred at least once between the first settlement of accounts and five years later. For simplicity, we denote the first settlement of accounts as the ‘first term,’ and the period five years later as the ‘second term.’Footnote14

Moreover, in this paper, we employ two types of definitions of switching firm–main bank relationships: narrow and broad.

In the narrow sense, switching firm–main bank relationships includes only the case where a firm switches its main bank to another financial institution in a completely different group. Thus, this case completely eliminates the possibility that a firm’s ex-post main bank is an affiliated financial institution of its ex-ante main bank.

In contrast, in the broad sense, switching main bank relationships includes almost all switching patterns.Footnote15 In this definition, we judge switching only by whether the name of a firm’s main bank changes between the first and second terms. This definition includes the case where the name changes because of the merger of banks, and thus, the main bank of a firm in the second term may be an affiliated financial institution of its main bank in the first term.

As noted earlier, we divide switching firm–main bank relationships into ‘transfer’ and ‘new transaction.’ These two types of switching are used as the variables TRANSFER and NEW_TRANSACTION, and we explain their definitions and differences in Section 5.2 (Variables).

Firm bankruptcy

To examine the effects of switching firm–main bank relationships on the probability of firm bankruptcy, we focus on firm bankruptcy that occurred within one year from the second term. Hence, the aim of this paper is, as it were, to investigate how switching firm–main bank relationships in the past five years affects the probability that a client firm will go bankrupt in the following year. shows the timeline of switching firm–main bank relationships and the bankruptcy of firms. The bankruptcy rate of the switching group is 3.3%, while that of the non-switching group is 1.5% (not reported). The differences between the two groups are statistically insignificant at the 10% level. Furthermore, the bankruptcy rate of all firms is 1.7%.Footnote16

Our definition of firm bankruptcy is based on the TSR Bankrupt Information File, which defines bankrupt firms as firms that fall under any of the following: suspension of transactions, application of Corporate Rehabilitation Law, insolvency, voluntary liquidation, special liquidation, and application of Civil Rehabilitation Law.

V. Empirical methodology and results

Methodology

Using the dataset just described, we employ switching in the narrow sense and examine the effects of switching firm–main bank relationships on the probability of firm bankruptcy. To investigate these effects, we must address a possible selection bias because a firm that is likely to switch its main bank relationship may innately tend to go bankrupt. To mitigate this problem, we use the propensity score matching estimation approach. Under the assumption that treatment assignment is strongly ignorable, this estimation approach enables us to accurately estimate causal effects even if the treatment assignment depends on covariates (Rosenbaum and Rubin Citation1983). In other words, under this assumption, we can obtain unbiased estimates of the effects of switching firm–main bank relationships on the probability of firm bankruptcy, even if the switching is endogenous before matching. The procedure for this approach is as follows.

First, to calculate the propensity scores, we conduct probit estimations, which model the probability that a firm switches its main banking relationship conditional on the covariates described in Section 5.2 (Variables). Next, for each treatment observation, the matched observation is selected from the sample of non-switching firms with the ‘closest’ propensity score. In this paper, to exclude arbitrariness from our propensity score matching estimations (i.e. researcher discretion), we employ two matching algorithms (i.e. nearest neighbour matching and 5-nearest neighbour matching).Footnote17 If we obtain statistically significant results in both these matching algorithms, our results are likely to support the hypotheses. Finally, we examine the effects of switching on the probability of bankruptcy by employing the matched observations. In this estimation, we use an average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) estimator.

Variables

shows the variable definitions and presents the descriptive statistics. BANKRUPTCY is the dependent variable, which is equal to one if a firm goes bankrupt within one year from the second term. SWITCH, TRANSFER, and NEW_TRANSACTION are our key explanatory variables. These variables are the dummies for switching firm–main bank relationships. Specifically, SWITCH equals one if a firm switches its main banking relationship between the first and second terms. TRANSFER and NEW_TRANSACTION are subsets of SWITCH. TRANSFER means switching a main bank to another financial institution with which the firm has already transacted in the first term. NEW_TRANSACTION means switching a main bank to another financial institution with which the firm has not transacted in the first term.

Table 1. Variable definitions.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Among other explanatory variables, we employ three categories that represent firm characteristics, firm financial information, and prefecture characteristics. Specifically, we use the following firm characteristic variables: number of correspondent financial institutions (BANKS), firm age (FIRM_AGE), manager age (MANAGER_AGE), a dummy indicating whether the manager of the firm is male (MALE), and the normalized credit score from TSR (SCORE). These variables are taken from the TSR Enterprise Information File.Footnote18 In addition, we use the following firm financial information variables: total assets (TOTAL_ASSETS), total liabilities (TOTAL_LIABILITIES), accrued expenses (ACCRUED_EXPENSES), capital (CAPITAL), difference between short-term and long-term borrowing in the first term (D_BORROWING_F), such difference in the second term (D_BORROWING_S), and change rate of D_BORROWING_F and D_BORROWING_S (D_BORROWING).Footnote19 These variables are taken from the TSR Stand-Alone Financial Information File. Moreover, the following are aggregate data for each prefecture: the ratio of the number of financial institutions to the number of ordinary corporations (BANKS_RATIO) and the start-up rate of small and unlisted enterprises (STARTUP_RATE). BANKS_RATIO is taken from Nihon Kinyu Meikan and the Number of Prefectural Sorted Ordinary Corporation. STARTUP_RATE is taken from Orbis. Dummy variables for accounting year, industry, type of main bank, and prefecture are also included in the regressions.

Baseline estimations

Results

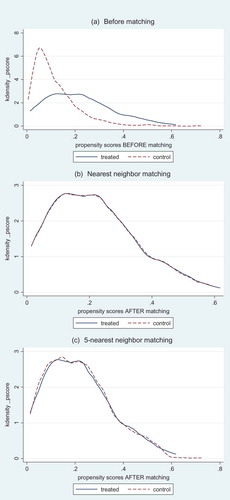

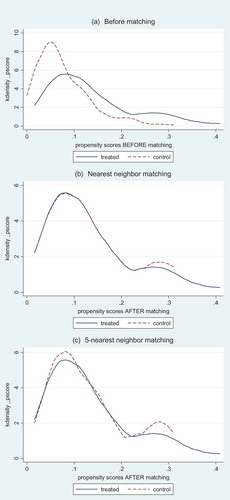

reports the results of the probit regressions with dependent variables SWITCH, TRANSFER, and NEW_TRANSACTION. We check for covariate balance of rows (1), (3), (4), and (6) in , and show the results in and ; indicates the results whose treatment is SWITCH and indicates the results whose treatment is NEW_TRANSACTION.Footnote20 In , the two groups are likely to be sufficiently similar to reduce selection bias in the treatment effect estimations when we employ nearest neighbour matching (). In addition, although there is slight deviation between the treatment and control groups even after the matching when we employ 5-nearest neighbour matching (), we can confirm that the balancing property is satisfied, and thus, the two groups are also likely to be sufficiently similar to reduce selection bias.

Table 3. Probit estimations of switching.

Table 4. Treatment effect estimations for firm bankruptcy (in the narrow sense of switching).

In Table 3, the marginal effects of BANKS are positive and statistically significant in columns (1) and (2), indicating that firms with many bank relationships are more likely to switch their main banks and the switching is more likely to be caused by a transfer. This is natural because these firms have more opportunities to transfer their main bank relationships. FIRM_AGE have negative marginal effects in columns (1) and (3), suggesting that younger firms are more likely to switch their main banks to other financial institutions with which the firms do not transact before the switching. The marginal effect of MANAGER_AGE is significantly negative in column (1), implying that younger managers tend to switch their main banks. MALE have negative marginal effects in columns (1) and (3), suggesting that male managers are conservative in switching main bank relationships to financial institutions with which the firms do not have long relationships. Alternatively, female managers may be offered loans under favourable terms by financial institutions that become their firms’ new main banks. In addition, the marginal effect of TOTAL_ASSETS is positive and statistically significant in column (3), implying that firms with more assets tend to switch their main banks to financial institutions with which the firms do not transact before the switching. The marginal effects of CAPITAL are positive and statistically significant in columns (1) and (2), suggesting that firms with more capital are more likely to transfer their main banks.

Turning to the treatment effects of switching firm–main bank relationships, reports the results of unmatched and ATT estimators. In , we employ nearest neighbour matching as a matching algorithm, and rows (1)–(3) report the results of estimations using SWITCH, TRANSFER, and NEW_TRANSACTION as the treatments, respectively. In row (1), SWITCH is statistically insignificant for the unmatched estimator. Thus, we do not find evidence that switching firm–main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy before dealing with the possible selection bias. In contrast, SWITCH is positive and statistically significant at the 5% level for the ATT estimator, which is consistent with Hypothesis 1. This result also indicates that switching firm–main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy by 3.3 percentage points. The economic impact of this estimator is not negligible because the percentage of bankrupt firms in our sample is 1.7%. In row (2), TRANSFER are positive, but are statistically insignificant for both the unmatched and ATT estimators. Thus, we find no evidence that the transfer of firm–main bank relationships affects the probability of firm bankruptcy. This result is consistent with Hypothesis 2. In row (3), NEW_TRANSACTION are positive and statistically significant at the 5% level for the unmatched estimator and at the 10% level for the ATT estimator. This result indicates that the ‘new transaction’ of firm–main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy by 4.1 percentage points after addressing the possible selection bias, which is also consistent with Hypothesis 2. In addition, as with the result in row (1), the economic magnitude of this estimator is important.

Next, we conduct the same analysis as in by employing 5-nearest neighbour matching as a matching algorithm. reports the results of this matching algorithm. In row (4), although SWITCH is statistically insignificant for the unmatched estimator, it is positive and statistically significant at the 10% level for the ATT estimator. This result is also consistent with Hypothesis 1. In addition, similar to , switching firm–main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy by 3.1 percentage points. The result in row (5) is also similar to that in row (2), that is, TRANSFER are positive but statistically insignificant for the unmatched and ATT estimators, which is consistent with Hypothesis 2. Moreover, the result in row (6) is the same as that in row (3). In other words, NEW_TRANSACTION are positive and statistically significant at the 5% level for the unmatched estimator and significant at the 10% level for the ATT estimator, and the ‘new transaction’ of firm–main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy by 4.1 percentage points after accounting for selection bias, which is also consistent with Hypothesis 2.

All in all, the results in support Hypotheses 1 and 2.

Discussion

Here, we consider the effects of unobservable factors on the results obtained in Section 5.3.1 (Results). In the propensity score matching estimations in Section 5.3.1 (Results), we observed that switching firm–main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy and only the ‘new transaction’ of firm–main bank relationships increases this probability. However, we cannot deny the possibility that these results are not free of hidden bias, and thus, we must consider whether the results in Section 5.3.1 (Results) are still statistically significant even if unobserved confounders lead to overestimating the ATT estimators in .

As for unobservable factors, collateral and credit guarantees may be associated with such switching or bankruptcy. To consider whether these factors would be hidden bias, we explain the functions of collateral and credit guarantees in SME finance in Japan. Ono and Uesugi (Citation2005), who employ a Japanese dataset mainly consisting of SMEs, show that 73.9% of SMEs in Japan pledge collateral to their main banks and 51.7% of SMEs in Japan pledge credit guarantees to their main banks.Footnote21 They also suggest that younger firms are less likely to pledge them to their main banks. Our sample is also likely to include both firms that pledge them to their main banks and firms that do not.

Next, we consider the association between the use of collateral or credit guarantees and switching or bankruptcy. ‘Good’ firms are less likely to be required to pledge collateral and credit guarantees to their main banks and less likely to be terminated firm–main bank relationships by their main banks (exogenous switching for firms).Footnote22 However, these firms are more likely to switch such relationships due to firm circumstances (endogenous switching for firms) and this type of switching should not lead to bankruptcy. In the propensity score matching estimations in Section 5.3.1 (Results), we cannot identify exogenous and endogenous switching. Thus, the use of collateral and credit guarantees may be associated with switching. We assume that the use of these factors is associated with switching and check the robustness of the results in Section 5.3.1 (Results) in later sections. More specifically, we consider whether the results in Section 5.3.1 (Results) are still statistically significant even after considering the effects of unmeasured confounders on the results in by using Rosenbaum’s sensitivity analysis in Section 5.4.1 (Rosenbaum’s sensitivity analysis) and two-stage least squares (2SLS) regressions in Section 5.4.3 (2SLS regressions).

Robustness checks

Rosenbaum’s sensitivity analysis

To check whether the results in are free of hidden bias, we conduct a sensitivity analysis proposed by Rosenbaum (Citation2002). This analysis is useful to verify the extent to which the obtained ATT estimators are robust to unobserved confounders. If the estimated treatment effects are insensitive or not very sensitive to hidden bias, the assumption of strongly ignorable treatment assignment is likely to be satisfied.

In this subsection, we check the sensitivity of the results in rows (1), (3), (4), and (6) in . reports the results of this analysis. Columns (1) and (2) in correspond to rows (1) and (4) in , respectively, while columns (3) and (4) in correspond to rows (3) and (6) in , respectively. In , is a sensitivity parameter that measures the degree of departure from random assignment of treatment;

means the assumption of no hidden bias. In this sensitivity analysis, an increase of 0.05 in

indicates that the odds that treatment is assigned to firms in the switching group become 1.05 times higher.

Table 5. Rosenbaum’s sensitivity analyses.

In , column (1) indicates that is statistically significant at the 10% level up to

, suggesting that the result in row (1) in is statistically significant at the 10% level, even if the odds that the treatment is assigned to firms in the switching group become 1.05 times higher. In addition, column (2) indicates that

is statistically significant at the 5% level up to

and statistically significant at the 10% level up to

. This result indicates that the result in row (4) in is statistically significant at the 5% level even if the odds increase by 0.50 and is statistically significant at the 10% level even if the odds increase by 1.00. This is relatively strong evidence that the ATT estimator in row (4) in is robust to unobserved confounders, which simultaneously suggests that switching firm–main bank relationships significantly increases the probability of firm bankruptcy even if unobserved factors such as collateral and credit guarantees are associated with switching firm–main bank relationships or firm bankruptcy.

Turning to the results where the treatments are NEW_TRANSACTION, column (3) indicates that is statistically insignificant even if

, suggesting that the result in this matching algorithm is sensitive to hidden bias.Footnote23

In contrast, column (4) indicates that

is statistically significant at the 1% level up to

, statistically significant at the 5% level up to

, and statistically significant at the 10% level up to

, suggesting that the result in row (6) in is statistically significant at the 1% level even if the odds increase by 0.20, statistically significant at the 5% level even if the odds increase by 1.25, and statistically significant at the 10% level even if the odds increase by 2.30. This result is insensitive to hidden bias, and thus, the ‘new transaction’ of firm–main bank relationships is also likely to significantly increase the probability of firm bankruptcy even after taking into account collateral and credit guarantees that are not controlled for, but may nevertheless be associated with switching and bankruptcy.

On balance, the results where the treatments are SWITCH and NEW_TRANSACTION are insensitive to hidden bias, suggesting that the obtained estimates of the treatment effects in Table 4 are still statistically significant even if unobservable confounders lead to overestimating the ATT estimators.

Discussion

Here, we consider the problems of propensity score matching estimations raised by King and Nielsen (Citation2016); specifically, we discuss the problems of imbalance, inefficiency, model dependence, and bias. King and Nielsen (Citation2016) argue that pruning observations at random increases imbalance because a decrease in sample size increases variance. More variance means more model dependence, and this dependence increases researcher discretion. In addition, random pruning increases bias; that is, the overestimation of treatment effects. However, King and Nielsen (Citation2016) show that these problems are not serious when the number of pruned observations is small. In this sense, 5-nearest neighbour matching is better than nearest neighbour matching.Footnote24 Moreover, King and Nielsen (Citation2016) also indicate that these problems are not serious when the number of pruned observations is less than 2,000. In this paper, such numbers in all treatment effect estimations are less than 1,000 even if we employ one-to-one matching without replacement. This implies that as long as treatment assignments are strongly ignorable, we can accurately estimate the effects of switching firm–main bank relationships on the probability of firm bankruptcy, even if the switching is endogenous before matching.Footnote25

2SLS regressions

Although the results in Section 5.3.1 (Results) indicated that switching firm–main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy and considered the robustness of these results in Sections 5.4.1 (Rosenbaum’s sensitivity analysis) and 5.4.2 (Discussion), we do not identify a case of switching caused by firms and that by financial institutions. In addition, unobservable firm characteristics (e.g. collateral and credit guarantees) may still be associated with such switching or bankruptcy. Therefore, to obtain further robust results in Section 5.3.1 (Results), we conduct a 2SLS regression of the form:

where is a dummy variable that indicates whether firm

goes bankrupt within one year from the second term (i.e. the variable BANKRUPTCY falls under it).

is the same as the previously defined NEW_TRANSACTION for firm

and is a key variable of interest in this regression. Here, we regard

as endogenous and employ an instrumental variable BANK_MERGER_SWITCH explained below.

and

show the characteristics of firm

: the former includes basic information and the latter includes financial information on the firm.

represents the characteristics of the prefecture in which firm

resides.

is a mean zero error term that encompasses unobservable factors. In this regression, we use cluster-robust standard errors with respect to firms.

Next, we explain the instrumental variable BANK_MERGER_SWITCH. This is a dummy variable that equals one if a firm’s ex-ante main bank is absorbed by another financial institution, and thus, the firm switches its main bank between the first and second terms to another financial institution with which it does not transact in the first term. In other words, BANK_MERGER_SWITCH is NEW_TRANSACTION occurred since a firm’s ex-ante main bank is absorbed by another financial institution. Owing to Hypothesis 2, we exclude cases of switching by such mergers to financial institutions with which the firms have transacted before switching. Bank mergers reduce credit availability for small firms (Sapienza Citation2002) and mergers between small banks decrease soft information acquisition (Ogura and Uchida Citation2014). However, these effects occur as a result of mergers, and thus, the ex-ante characteristics of client firms should not be associated with the mergers of ex-ante main banks. Therefore, BANK_MERGER_SWITCH should be exogenous to client firm characteristics. Furthermore, BANK_MERGER_SWITCH is likely to be associated with NEW_TRANSACTION because BANK_MERGER_SWITCH is a subset of NEW_TRANSACTION. To summarize, BANK_MERGER_SWITCH is likely to satisfy the conditions of instrumental variables: instrument exogeneity and instrument relevance.

reports the results of the first-stage regression where the dependent variable is NEW_TRANSACTION. Column (1) is the full specification and columns (2) and (3) are the parsimonious specifications that use selected explanatory variables. Specifically, in columns (2) and (3), we use only the variables that are statistically significant in column (1). As for the variable of interest, the coefficients on BANK_MERGER_SWITCH are significantly negative at the 1% level in all columns, indicating that unrecognizable switching, whether endogenous or exogenous, decreases with an increase in recognizable exogenous switching. This result also indicates that BANK_MERGER_SWITCH satisfies instrument relevance in these columns.

Table 6. 2SLS regressions (first-stage regressions).

reports the results of the second-stage regression where the dependent variable is BANKRUPTCY. As for the variable of interest, the coefficients on NEW_TRANSACTION are positive and statistically significant at the 10% level in column (1), 5% level in column (2), and 1% level in column (3), suggesting that switching due to the circumstances of the ex-ante main banks (i.e. exogenous switching for client firms) increases the probability of firm bankruptcy. Specifically, in these columns, such switching increases the probability of bankruptcy by 19.6–43.6 percentage points, indicating that these effects are economically important. The economic magnitude of these variables is about 4.8–10.6 times as much as the results in and , implying that the effect of exogenous switching for client firms on the probability of bankruptcy is larger than that of switching in general. This is an expected result because exogenous switching tends to occur when client firms are not good borrowers for their main banks, whereas endogenous switching tends to occur only when firms can obtain new financing with better lending terms and conditions from their new main banks.

Table 7. 2SLS regressions (second-stage regressions).

Furthermore, in all columns, the results of Wooldridge’s (Citation1995) score test of overidentifying restrictions, which are robust to heteroscedasticity, are statistically insignificant at the 10% level. These results suggest that the variable NEW_TRANSACTION is not endogenous, simultaneously implying that the ATT estimators for NEW_TRANSACTION in rows (3) and (6) in are not biased by unobserved factors such as collateral and credit guarantees.

VI. Further analyses

From the analyses thus far, we find that switching firm–main bank relationships increases the probability of firm bankruptcy. The next questions that naturally arise are as follows. First, does switching such relationships that is not accompanied by the termination of ex-ante firm–bank relationships also increase the probability of bankruptcy? Second, why does switching increase the probability of bankruptcy? Although the precise identification of the true mechanisms is empirically difficult, in this section, we consider these two questions by conducting two analyses. The first is an analysis of the effects of switching in the broad sense on the probability of firm bankruptcy, and the second is an analysis of the path to bankruptcy.

Effects of switching in the broad sense on the probability of firm bankruptcy

In this subsection, we examine whether switching that is not accompanied by the termination of ex-ante firm–bank relationships also increases the probability of bankruptcy, which also tests Hypothesis 2. To investigate it, we replace the definition of switching in the narrow sense defined in Section 4.2 (Switching main bank relationships) with switching in the broad sense and conduct the same analyses as in Section 5.3.1 (Results). As mentioned earlier, switching in the broad sense includes almost all patterns of switching. Unfortunately, data limitations prevent us from using only firms that switch their main banks to affiliated financial institutions of their ex-ante main banks. Therefore, we use switching in the broad sense and investigate how switching firm–main bank relationships affects the probability of firm bankruptcy.

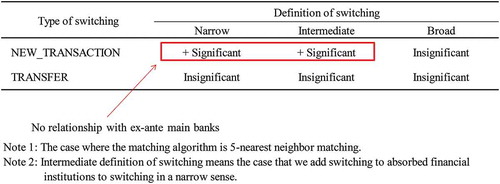

reports the results for the unmatched and ATT estimators. Although the structure of is similar to that of , the definitions of SWITCH, TRANSFER, and NEW_TRANSACTION in are different from those in ; SWITCH, TRANSFER, and NEW_TRANSACTION in are defined in the broad sense, whereas those in are defined in the narrow sense.

Table 8. Treatment effect estimations for firm bankruptcy (in the broad sense of switching).

Similar to in , the ATT estimators for SWITCH and NEW_TRANSACTION are positive and statistically significant in . In contrast, unlike the results in , the ATT estimators of SWITCH and NEW_TRANSACTION are both statistically insignificant in . Indeed this result does not mean that switching in the broad sense does not increase the probability of firm bankruptcy, but only means that there is no evidence that such switching increases the probability of bankruptcy. However, the result in implies that switching firm–main bank relationships does not increase the probability of firm bankruptcy when the ex-post main banks are affiliated financial institutions of ex-ante main banks. This is because at least one of the ATT estimators for SWITCH and NEW_TRANSACTION in should be statistically significant if switching to affiliated financial institutions of their ex-ante main banks also increases the probability of firm bankruptcy. Thus, switching to financial institutions with which they have transacted before switching is unlikely to increase the probability of firm bankruptcy. This result is consistent with Hypothesis 2.

The reason we obtain the results that the ATT estimators for SWITCH and NEW_TRANSACTION are statistically significant in , where we employ nearest neighbour matching as a matching algorithm, is likely to be that we cannot use only firms that switch their main banks to affiliated financial institutions of their ex-ante main banks due to data limitations.Footnote26 In other words, these estimators are statistically significant in may be because selected observations in are almost the same as those in . In contrast, the reason such estimators are statistically insignificant in is likely to be that several matched observations, which are not selected in , are selected from firms that switch their main banks to affiliated financial institutions of their ex-ante main banks.

It should also be noted that we obtain similar results to those in concerning the ATT estimator for NEW_TRANSACTION when we exclude switching to absorbing financial institutions from switching in the broad sense (results not reported).Footnote27 These results imply that although soft information is communicated when firms switch their main banks because ex-ante main banks absorb other financial institutions, it is not communicated when ex-ante main banks are absorbed by other financial institutions. In summary, the probability of firm bankruptcy may increase when firms switch their main banks to financial institutions that do not have soft information about them. This is consistent with our expectations and it suggests that only the ‘new transaction’ by exogenous switching for firms increases the probability of bankruptcy.Footnote28 Thus, this result also suggests that switching to financial institutions with which they have transacted before switching does not increase the probability of firm bankruptcy, supporting Hypothesis 2.

These results are summarized in .

Path to bankruptcy

Finally, we examine the path to bankruptcy. As mentioned in Section 3 (Empirical hypotheses), we expect that switching firm–main bank relationships prevents firms from refinancing short-term borrowing with long-term borrowing, and thus, leads to bankruptcy. In this subsection, we investigate two causal relationships: (1) the relationship between switching and the change rate of the dependence on short-term borrowing; (2) and the relationship between this change rate and bankruptcy.

First, we examine the effect of switching on the change rate of dependence on short-term borrowing by employing the propensity score matching estimations. It should also be noted that there is little difference in dependence on short-term borrowing between the switching and non-switching groups in the first term (i.e. before switching). The procedure for creating such change rate is as follows. We take the difference between short-term and long-term borrowing in the first and second terms, and calculate the change rate between the two terms.

reports the result of the probit regression where the dependent variable is SWITCH. The balancing property in this matching is also satisfied (not reported), suggesting that the treatment and control groups after the matching are likely to be sufficiently similar to reduce selection bias in these treatment effect estimations.Footnote29 In , the number of observations is 646 (not 1,008) because some of the observations are omitted in the second term. The marginal effects of BANKS and SCORE are positive and statistically significant, and those of FIRM_AGE, MANAGER_AGE, and MALE are significantly negative, indicating that these covariates are likely to affect switching firm–main bank relationships (SWITCH). Turning to the treatment effect of SWITCH on the change rate of dependence on short-term borrowing (D_BORROWING), reports the results of the unmatched and ATT estimators; specifically, rows (1) and (2) in report the results when we employ nearest neighbour matching and 5-nearest neighbour matching as matching algorithms, respectively. The ATT estimators for SWITCH are statistically significant at the 5% level in row (1) and 10% level in row (2), suggesting that switching firm–main bank relationships prevents firms from refinancing short-term borrowing with long-term borrowing.

Table 9. Probit estimation of switching.

Table 10. Treatment effect estimations for dependence on short-term borrowing.

Next, we examine the relationship between the change rate of the dependence on short-term borrowing and firm bankruptcy. Unfortunately, we cannot perform regression analyses owing to the small sample, and thus, we compare the change rate between continuing and bankrupt firms. As a result, this rate in continuing firms is 43.8% and for the bankrupt firms is 31.8% (not reported), implying that bankrupt firms struggle to refinance from short-term to long-term borrowing. However, this difference (43.8% and 31.8%) is statistically insignificant, likely because our sample size is small. Hence, we compare the ratio of short-term borrowing to total borrowing between continuing and bankrupt firms in the second term (immediately before bankruptcy for bankrupt firms). reports this ratio; more specifically, includes all observations and includes only the matched observations.Footnote30 In , the ratio of short-term borrowing to total borrowing in continuing firms is 37.2%, while that ratio in bankrupt firms is 66.5%. This difference is statistically significant at the 5% level. Similarly, in , this difference (35.4% and 74.1%) is also statistically significant at the 5% level, suggesting that high dependence on short-term borrowing increases the probability of firm bankruptcy.

Table 11. Ratio of short-term borrowing to total borrowing.

In summary, switching firm–main bank relationships prevents firms from refinancing with long-term borrowing, and thus, high dependence on short-term borrowing is likely to increase the probability of firm bankruptcy.

VII. Conclusion

Employing a unique firm-level dataset, we examined the effects of switching firm–main bank relationships on the probability of firm bankruptcy. We find that switching increases the probability of firm bankruptcy. In particular, our results suggest that switching increases the probability of bankruptcy when firms switch their main banks to financial institutions with which they have not previously transacted before switching. In addition, we find that the results hold only when the ex-post main banks are not affiliated financial institutions of their ex-ante main banks. These results are likely because such switching prevents firms from refinancing with long-term borrowing, and thus, leads to bankruptcy. Moreover, we obtain robust results by employing Rosenbaum’s sensitivity analysis and 2SLS regression, and thus, our results are unlikely to be driven by omitted variables. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the economic magnitude of exogenous switching for client firms is larger than that of switching in general. These results are consistent with prior studies on relationship lending.

Our findings also suggest that many important issues remain to be addressed in future research. For example, the type of switching (endogenous or exogenous) that increases the probability of firm bankruptcy is an important research topic. Although our results suggest that the economic impact of exogenous switching for client firms is larger than that of endogenous switching, examining the effect of each switching on bankruptcy in more detail is an interesting avenue for future studies. In this respect, we expect that endogenous switching does not increase the probability of bankruptcy because firms do not switch their main banks unless lending terms and conditions improve, let alone the case of the ‘new transaction.’ The improvement in lending terms and conditions is unlikely to increase the probability of bankruptcy. Furthermore, exploring other paths to bankruptcy and examining the effects of switching firm–main bank relationships on firm bankruptcy, while explicitly controlling for the variables that represent soft information, are also intriguing topics for future research.

Acknowledgments

This study is conducted as a part of the Project “The Role of Regional Financial Institutions towards Regional Revitalization: How do regional financial institutions contribute to improving the quality of employment in the local economy?” undertaken at the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI). I would like to thank an anonymous referee, Shin-ichi Fukuda, Nobuaki Hamaguchi, Kozo Harimaya, Mohammad Hoque, Kazuyuki Inagaki, Karin Jõeveer, Daiji Kawaguchi, Yoko Konishi, Eiji Mangyo, Daisuke Miyakawa, Masayuki Morikawa, Eriko Naiki, Jiro Nemoto, Hikaru Ogawa, Arito Ono, Masahiko Shibamoto, Tadashi Sonoda, Hidenori Takahashi, Yoshiro Tsutsui, Hirofumi Uchida, Ichihiro Uchida, Iichiro Uesugi, Nobuyoshi Yamori, Makoto Yano, and Kazuki Yokoyama, as well as the participants at the World Business Research Conference, the 9th Regional Finance Conference, the 12th Modern Monetary Economics Summer Institute (MME SI) in Kobe, the SIBR 2015 Hong Kong Conference on Interdisciplinary Business & Economics Research, the 2015 Autumn Meeting of the Japanese Economic Association, the 2015 Autumn Annual Meeting of the Japan Society of Monetary Economics, the 10th Applied Econometrics Conference, the 2015 World Finance & Banking Symposium, the 1st Chubu Area Study Group of the Japan Society of Monetary Economics in 2016, the Monetary Economics Workshop, RIETI, and the NCU and Chubu JSME Research Workshop 2017 on Accounting & Finance for their helpful comments. I am also grateful to Leo Iijima, Graduate Program for Real-World Data Circulation Leaders, which is one of Nagoya University’s Leading Graduate School Programs, and Tokyo Shoko Research, Ltd. for data provision. All remaining errors are my own responsibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This report indicates that most young firms exit during the early stages of the entrepreneurial process, and that the exit rate of start-up companies gradually diminishes as they grow.

2 The probability of bankruptcy per year among these firms is much higher than among other enterprises.

3 According to the theoretical models presented by Sharpe (Citation1990) and Rajan (Citation1992), close firm–bank relationships increase the cost of switching main banks.

4 Main banks play a broad role in Japan (Sheard Citation1994). Therefore, in Japanese cases, the definition of ‘main banks’ differs in each study.

5 Keiretsu firms and their main banks have very close relationships (Hoshi, Kashyap, and Scharfstein Citation1991; Wu and Yao Citation2012). For details on the keiretsu, see Miwa and Ramseyer (Citation2002).

6 As previously mentioned, to our knowledge, no study except Gambini and Zazzaro (Citation2013) conducts a direct empirical analysis on the effects of continuation of firm–main bank relationships on the performance of small firms.

7 In this case, firms go bankrupt even if they have black balance sheets.

8 However, Bharath et al. (Citation2011) imply that loan terms from prior lenders are better; they suggest that long-lasting relationships with financial institutions benefit financially opaque firms.

9 Berger and Udell (Citation1998) argue that SMEs have difficulty obtaining external financing despite their strong desire for outside funds owing to information asymmetries between firms and financial institutions.

10 Even if our sample includes firms with high creditworthiness, these firms should be excluded from the sample through propensity score matching procedures.

11 Note that we discuss whether switching firm–main bank relationships prevents firms from refinancing short-term borrowing with long-term borrowing, and thus, it leads to bankruptcy in Section 6.2 (Path to bankruptcy).

12 According to the Annual Report of Bankrupt Enterprises (published by the Organization for Small & Medium Enterprises and Regional Innovation, Japan), approximately 95% of bankrupt firms in Japan have less than 50 million yen in capital.

13 Previous studies that focus on SMEs generally define main banks as banks at the head of bank name lists of firms and these financial institutions are often the largest lending banks for client firms in these studies.

14 Note that the data on bankrupt firms comprise information on the first settlement term and the term immediately before bankruptcy because these firms went bankrupt within five years of the first settlement. Hence, for bankrupt firms, we denote the term immediately before bankruptcy as the ‘second term.’

15 In the broad sense, the number of switching is 135.

16 In this paper, the percentage of firm bankruptcies per year is smaller than usual because our sample is unique.

17 Previous studies caution that researchers should remove the biases associated with their discretion in selecting matching algorithms (e.g. Ho et al. Citation2007; King and Nielsen Citation2016).

18 Firm age is the number of years from establishment. However, for firms with unclear establishment dates, we substitute the number of years from incorporation for those from establishment.

19 Short-term borrowing represents the borrowing that a firm must repay within one year from the day following the date of account closing.

20 The results of our balance tests show that all covariates are jointly insignificant at the 10% level in the estimations shown in and (not reported). In addition, we obtain the same results when we include the outcome variable (not reported). Although we cannot directly check the assumption of conditional uncorrelation between the outcome and the treatment, these results imply that this assumption is satisfied.

21 We introduce the data used in Ono and Uesugi (Citation2005), which is a previous version of Ono and Uesugi (Citation2009), because the use rate of credit guarantees is not reported in Ono and Uesugi (Citation2009).

22 ‘Good’ firms mean firms with low risk of bankruptcy.

23 Because the way of eliminating outliers in Rosenbaum’s sensitivity analysis differs from that in propensity score matching estimation, is statistically insignificant even if

.

24 In fact, Jann (Citation2017) argues that 5-nearest neighbour matching is less affected by these problems.

25 We discuss the assumption that treatment assignment is strongly ignorable in Section 5.4.1 (Rosenbaum’s sensitivity analysis).

26 As previously mentioned, switching in the broad sense includes not only firms that switch their main banks to affiliated financial institutions of their ex-ante main banks, but also those switch them to non-affiliated financial institutions.

27 In other words, NEW_TRANSACTION still increases the probability of bankruptcy even if we add ‘switching to absorbed financial institutions’ to ‘switching in the narrow sense.’ This type of switching falls under the intermediate definition of switching in Figure 4.

28 We discuss further in Section 7 (Conclusion).

29 The result of a balance test shows that all covariates are jointly insignificant at the 10% level (not reported). Furthermore, we obtain the same results when we include the outcome variable in the balance test (not reported).

30 The number of observations in (647 observations) is one more than those in and (646 observations) because one observation is omitted in the estimations in and due to multicollinearity.

References

- Altman, E. I. 1968. “Financial Ratios, Discriminant Analysis and the Prediction of Corporate Bankruptcy.” Journal of Finance 23: 589–609.

- Berger, A. N., R. J. Rosen, and G. F. Udell. 2007. “Does Market Size Structure Affect Competition? The Case of Small Business Lending.” Journal of Banking & Finance 31: 11–33.

- Berger, A. N., and G. F. Udell. 1995. “Relationship Lending and Lines of Credit in Small Firm Finance.” Journal of Business 68: 351–381.

- Berger, A. N., and G. F. Udell. 1998. “The Economics of Small Business Finance: The Roles of Private Equity and Debt Markets in the Financial Growth Cycle.” Journal of Banking & Finance 22: 613–673.

- Berlin, M., and L. J. Mester. 1998. “On the Profitability and Cost of Relationship Lending.” Journal of Banking & Finance 22: 873–897.

- Bharath, S. T., S. Dahiya, A. Saunders, and A. Srinivasan. 2011. “Lending Relationships and Loan Contract Terms.” Review of Financial Studies 24: 1141–1203.

- Boot, A. W. A. 2000. “Relationship Banking: What Do We Know?” Journal of Financial Intermediation 9: 7–25.

- Boot, A. W. A., and A. V. Thakor. 1994. “Moral Hazard and Secured Lending in an Infinitely Repeated Credit Market Game.” International Economic Review 35: 899–920.

- Brick, I. E., and D. Palia. 2007. “Evidence of Jointness in the Terms of Relationship Lending.” Journal of Financial Intermediation 16: 452–476.

- Chemmanur, T. J., and P. Fulghieri. 1994. “Reputation, Renegotiation, and the Choice between Bank Loans and Publicly Traded Debt.” Review of Financial Studies 7: 475–506.

- Cole, R. A. 1998. “The Importance of Relationships to the Availability of Credit.” Journal of Banking & Finance 22: 959–977.

- Degryse, H., and P. V. Cayseele. 2000. “Relationship Lending within a Bank-Based System: Evidence from European Small Business Data.” Journal of Financial Intermediation 9: 90–109.

- Diamond, D. W. 1989. “Reputation Acquisition in Debt Markets.” Journal of Political Economy 97: 828–862.

- Diamond, D. W. 1991. “Monitoring and Reputation: The Choice between Bank Loans and Directly Placed Debt.” Journal of Political Economy 99: 689–721.

- Farinha, L. A., and J. A. C. Santos. 2002. “Switching from Single to Multiple Bank Lending Relationships: Determinants and Implications.” Journal of Financial Intermediation 11: 124–151.

- Fukuda, S., M. Kasuya, and K. Akashi. 2009. “Impaired Bank Health and Default Risk.” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 17: 145–162.

- Fukuda, S., and S. Koibuchi. 2007. “The Impacts of “Shock Therapy” on Large and Small Clients: Experiences from Two Large Bank Failures in Japan.” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 15: 434–451.

- Gambini, A., and A. Zazzaro. 2013. “Long-Lasting Bank Relationships and Growth of Firms.” Small Business Economics 40: 977–1007.

- Gopalan, R., G. F. Udell, and V. Yerramilli. 2011. “Why Do Firms Form New Banking Relationships?” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 46: 1335–1365.

- Grunert, J., and M. Weber. 2009. “Recovery Rates of Commercial Lending: Empirical Evidence for German Companies.” Journal of Banking & Finance 33: 505–513.

- Hanazaki, M., and A. Horiuchi. 2000. “Is Japan’s Financial System Efficient?” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 16: 61–73.

- Harhoff, D., and T. Körting. 1998. “Lending Relationships in Germany – Empirical Evidence from Survey Data.” Journal of Banking & Finance 22: 1317–1353.

- Ho, D. E., K. Imai, G. King, and E. A. Stuart. 2007. “Matching as Nonparametric Preprocessing for Reducing Model Dependence in Parametric Causal Inference.” Political Analysis 15: 199–236.

- Hori, M. 2005. “Does Bank Liquidation Affect Client Firm Performance? Evidence from a Bank Failure in Japan.” Economics Letters 88: 415–420.

- Hoshi, T., A. Kashyap, and D. Scharfstein. 1990. “The Role of Banks in Reducing the Costs of Financial Distress in Japan.” Journal of Financial Economics 27: 67–88.

- Hoshi, T., A. Kashyap, and D. Scharfstein. 1991. “Corporate Structure, Liquidity, and Investment: Evidence from Japanese Industrial Groups.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 106: 33–60.

- Ioannidou, V., and S. Ongena. 2010. “Time for a Change”: Loan Conditions and Bank Behavior when Firms Switch Banks.” Journal of Finance 65: 1847–1877.

- Jann, B., 2017. “Why Propensity Scores Should Be Used for Matching.” https://www.stata.com/meeting/germany17/slides/Germany17_Jann.pdf

- Kang, J.-K., and A. Shivdasani. 1999. “Alternative Mechanisms for Corporate Governance in Japan: An Analysis of Independent and Bank-Affiliated Firms.” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 7: 1–22.

- Kano, M. 2007. “When Does the Relationship Banking Break up? An Empirical Analysis in Kansai Area.” In Relationship Banking and Regional Finance, edited by Y. Tsutsui and S. Uemura, 101–123. in Japanese. Tokyo: Nikkei Publishing.

- King, G., and R. Nielsen. 2016. “Why Propensity Scores Should Not Be Used for Matching.” Working paper. https://gking.harvard.edu/files/gking/files/psnot.pdf

- Lichtenberg, F. R., and G. M. Pushner. 1994. “Ownership Structure and Corporate Performance in Japan.” Japan and the World Economy 6: 239–261.

- Mata, J. 1994. “Firm Growth during Infancy.” Small Business Economics 6: 27–39.

- Mayer, C. 1988. “New Issues in Corporate Finance.” European Economic Review 32: 1167–1189.

- Miwa, Y., and J. M. Ramseyer. 2002. “The Fable of the Keiretsu.” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 11: 169–224.

- Ogane, Y. 2016. “Banking Relationship Numbers and New Business Bankruptcies.” Small Business Economics 46: 169–185.

- Ogura, Y. 2012. “Lending Competition and Credit Availability for New Firms: Empirical Study with the Price Cost Margin in Regional Loan Markets.” Journal of Banking & Finance 36: 1822–1838.

- Ogura, Y., and H. Uchida. 2014. “Bank Consolidation and Soft Information Acquisition in Small Business Lending.” Journal of Financial Services Research 45: 173–200.

- Ongena, S., and D. C. Smith. 2001. “The Duration of Bank Relationships.” Journal of Financial Economics 61: 449–475.

- Ono, A., and I. Uesugi, 2005. “The Role of Collateral and Personal Guarantees in Relationship Lending: Evidence from Japan’s Small Business Loan Market.” RIETI Discussion Paper Series 05-E-027. https://www.rieti.go.jp/jp/publications/dp/05e027.pdf

- Ono, A., and I. Uesugi. 2009. “Role of Collateral and Personal Guarantees in Relationship Lending: Evidence from Japan’s SME Loan Market.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 41: 935–960.

- Petersen, M. A., and R. G. Rajan. 1994. “The Benefits of Lending Relationships: Evidence from Small Business Data.” Journal of Finance 49: 3–37.

- Prowse, S. D. 1992. “The Structure of Corporate Ownership in Japan.” Journal of Finance 47: 1121–1140.

- Rajan, R. G. 1992. “Insiders and Outsiders: The Choice between Informed and Arm’s-Length Debt.” Journal of Finance 47: 1367–1400.

- Rosenbaum, P. R. 2002. Observational Studies. 2nd ed. New York: Springer.

- Rosenbaum, P. R., and D. B. Rubin. 1983. “The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects.” Biometrika 70: 41–55.

- Sapienza, P. 2002. “The Effects of Banking Mergers on Loan Contracts.” Journal of Finance 57: 329–367.

- Sharpe, S. A. 1990. “Asymmetric Information, Bank Lending and Implicit Contracts: A Stylized Model of Customer Relationships.” Journal of Finance 45: 1069–1087.

- Sheard, P. 1994. “Main Banks and the Governance of Financial Distress.” In The Japanese Main Bank System: Its Relevance for Developing and Transforming Economies, edited by M. Aoki and H. Patrick, 188–230. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shimizu, K. 2012. “Bankruptcies of Small Firms and Lending Relationship.” Journal of Banking & Finance 36: 857–870.

- Tsuruta, D. 2014. “Changing Banking Relationships and Client Firm Performance: Evidence from Japan for the 1990s.” Review of Financial Economics 23: 107–119.

- Uchida, H., G. F. Udell, and W. Watanabe. 2008. “Bank Size and Lending Relationships in Japan.” Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 22: 242–267.

- Uchida, H., G. F. Udell, and N. Yamori. 2012. “Loan Officers and Relationship Lending to SMEs.” Journal of Financial Intermediation 21: 97–122.

- Weinstein, D. E., and Y. Yafeh. 1998. “On the Costs of a Bank-Centered Financial System: Evidence from the Changing Main Bank Relations in Japan.” Journal of Finance 53: 635–672.

- Wooldridge, J. M. 1995. “Score Diagnostics for Linear Models Estimated by Two Stage Least Squares.” In Advances in Econometrics and Quantitative Economics: Essays in Honor of Professor C. R. Rao, edited by G. S. Maddala, P. C. B. Phillips, and T. N. Srinivasan, 66–87. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Wu, X., and J. Yao. 2012. “Understanding the Rise and Decline of the Japanese Main Bank System: The Changing Effects of Bank Rent Extraction.” Journal of Banking & Finance 36: 36–50.

Appendix

This appendix considers whether the places where our sample firms reside are biased towards urban or rural prefectures. reports the distributions of firms, financial institutions, and BANKS_RATIO (i.e. the ratio of the number of financial institutions to that of ordinary corporations) by prefecture. shows that the number of prefectures whose number of ordinary corporations exceeds their average is 11 and those whose number of financial institutions exceeds their average is 14. If we define the prefectures that exceed both numbers as urban regions, the number of prefectures in urban regions is 11 and that of sample firms in urban regions is 607, which is 60.2% of the total number of sample firms. Thus, our sample might be biased towards urban regions. To mitigate such bias, we include dummy variables for prefecture as well as accounting year, industry, and type of main bank in almost all regressions.

Table A1. Distributions of firms and financial institutions by prefecture.