?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The professional survival of a coach can be explained by the ability of the team that he or she trains to achieve a reasonable number of points in relation to the total team’s budget. In this work, we test the microeconomic indicator of average cost as an important (and so far unassessed) dimension in the survival of a professional football coach in the face of recurrent defeats. For this purpose, we use empirical methods associated with survival analysis considering recurrent events. We analyse 1077 contract durations between the 2009/2010 and 2019/2020 seasons of the professional leagues in Spain, England, Italy, Germany, France and Portugal. We conclude that the average cost (total budget divided by points achieved in the national championships) is an important dimension. We also discuss other dimensions – such as clubs’ financial characteristics, neighbouring teams’ competitiveness or coaches’ individual characteristics – which, in certain leagues, also prove to be determinant.

KEYWORDS:

I. Introduction

The lives of head coaches have motivated recent studies that analyse a significant diversity of themes. Some of these themes are related to coaches’ emotional management throughout their careers (Lee, Park, and Nam Citation2013), relationships with players (Marwat et al. Citation2021), communication management (García-Mateo et al. Citation2020), and balancing of different groups in a squad (Dias and Vidya Citation2021), as well as the role of third parties (Ficken et al. Citation2021) and relationships with fans (Taylor and Garratt Citation2010).

One of the themes explored is what determines the survival capacity of sports agents. In addition to the greater volume of works focusing on the professional survival of players, a smaller stream explores the situations of other agents, such as referees (Frick Citation2012) or soccer coaches, as examined here. If, as Carmo (Citation2010) argues, each coach has unique characteristics that do not allow us to identify ‘general laws’ governing what happens at the end of the line in the case of each football team, it is also true that for coaches to better manage their careers, it is important that they can anticipate the most appropriate times to terminate a contract with their employer clubs. Additionally, for the team itself, managing a change in coach is part of any strategy aiming to optimize the competitive and financial goals of the club.

However, one of the main dimensions considered in this work has so far remained unexplored. Specifically, we here closely investigate the value of the total budget proposed for the sporting season, measuring this value by the points achieved in the main national championship. This variable, from a microeconomic perspective, has a clear correspondence with average cost, a concept duly prioritized in the strategy of each company or industry. By ‘budget’ we refer to the total budget for a professional soccer team, including expenses for coaches, athletes, travelling costs, administration and transfer fees. Following an established approach from economic theory, we leverage assumptions on how a competitive firm seeks to establish its production plan on the dimension that minimizes average cost. If the firm chooses different dimensions, it will tend to have lower supply and consequently lose market share (Bernheim and Whinston Citation2013). Management of a football team is no different – if a team cannot minimize its total costs, represented by the season budget, by achieving more points in the league table, it will tend to fall down in the table and increase its probability of having to reflect seriously.

Traditionally, a coach change has been seen as a more media-driven consequence of a change in strategy, given the restrictions on transfer windows (concentrated on specific periods throughout the season) and the limited budget allowed for a given season. Sacking a manager may be costly in the first place, particularly if the manager has a great deal of time remaining on his or her contract. Bringing in a new manager may also alter the budget (the new manager may want new players, etc.). These new costs tend to be smaller than the costs projected for the entire season. The overall effects of changing coaches (also called psychological whipping) have been detailed in works such as that by Silvestre (Citation2011). However, the direct relation of such psychological whipping with the average cost of points is concretely evaluated here.

The remaining sections of this work are organized as follows. Section II reviews the literature on the determinants of the contractual longevity of professional football coaches. Section III discusses the empirical results obtained from recurring-events estimation models based on data collected on coaches from 6 European leagues (in alphabetical order, England, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain). Finally, Section V concludes.

II. Literature review

The literature on the contractual longevity of sports team coaches has had, since the pioneering works of Koning (Citation2003) and Bruinshoofd and Weel (Citation2003), contributions enriched by several lines of research (Frick, Barros, and Passos Citation2006; Dobson and Goddard Citation2011; Addona and Kind Citation2014; Tyler and Sheridan Citation2020; Bryson et al. Citation2021). These lines of investigation generally cover the following six topics:

- financial pressures related to the team;

- pressures arising from the performance of competitive neighbourhood teams;

- personal dimensions of the coach;

- pressures arising from the sporting performance of the team;

- pressures arising from supervisory board members; and

− specificities of the professional league.

The first topic relates to the pressure that the spending – performance relationship places on the continuity of a coach who fails to raise his or her team’s performance. On the one hand, clubs characterized by more significant financial resources expect greater achievements from coaches and players (Ruano et al. Citation2021). Thus, teams with higher total budgets but also higher transfer flows in terms of contract values (Silva et al. Citation2020) are more demanding and have higher performances expectations. Traditionally, such teams have the strongest competitive history (Dobson and Goddard Citation2011; Mourao Citation2016), with the most supporters and followers (Rohde and Breuer Citation2016) and with more valued tangible assets and financial resources (Mourao Citation2012). These dimensions have traditionally been considered in isolation. However, we consider it pertinent to evaluate them in terms of one relational dimension – total budget per point. We also consider the square of this variable to analyse the nonlinearity in the relationship between contract duration and sports performance. This measure is associated with the concept of average cost, a traditional indicator in microeconomic analysis. Productive units seek to minimize this ratio in pursuit of efficiency goals (Frank Citation1998) and survive in competitive industrial environments. The analogy with sports team performance management is supported by studies such as that by Mourao (Citation2017) relating budget values to costs borne by sports units. The importance of holding average cost at its most efficient level to ensure the continuity of production units in the market was originally illustrated in the seminal contribution of Stigler (Citation1958). According to Stigler (Citation1958), units operating at the most efficient scale will most likely survive in their industry; therefore, identifying and achieving this scale is essential for each unit’s sustainability. From an updated perspective, coaches operating at the most efficient scale of points will most likely survive in their leagues. Even at the level of other industries, we find that the professional survival of CEOs depends on their firms’ performance (CORDEIRO and SHAW Citation2010).

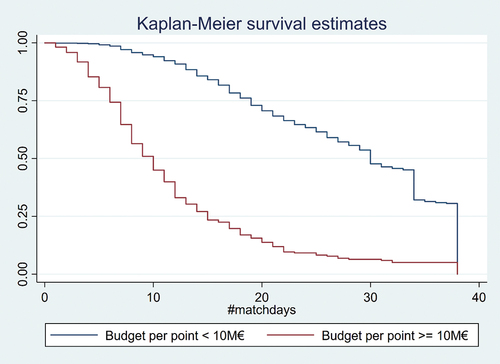

In our analysis considering the diversity of 1077 observed coaches () in the 6 leagues identified for seasons 2009/2010 and 2019/2020, we observe the following evidence:

Fifty percent of these individuals coached their teams for an average of 10 rounds at a level of 10 million euros per point or higher; however, 93% of them were able to train their own teams over the same number of matchdays but at a lower average cost (than 10 million euros per point).

Only 12% of the coaches were still working by the 20th matchday in the initial team of the season at an average cost of 10 million euros per point; this number contrasts with the 70% of the coaches who, by the same 20th matchday, were still working in the initial team of the season while achieving an average cost lower than 10 million euros per point.

Similar figures have been constructed with different thresholds (such as median euros per point); these figures are available upon request.

Figure 1. Survival of coaches over matchdays considering two different groups of total budgets divided by league points (6 European soccer leagues, 2009/2010–2019/2020).

Legend: Horizontal axis – analysis time (number of games); vertical axis – probability of survival beyond time t. Log-rank test (null hypothesis: equal estimates) – p value: 0.0002 (<0.001)

Additionally, given that goals are the soccer teams’ primary objective (Lee Citation2014), we include an analysis of each team’s total budget for the season divided by the number of goals in favour.

The dimension of pressure arising from the performance of other teams that usually compete for the same exclusive ranks as a given team has been studied by Addona and Kind (Citation2014). Specifically, it is assumed, for example, that as the place of champion in a competition is exclusive, the few teams that traditionally compete for this top spot will tend to compare performances more frequently among themselves than with teams that usually finish ten places below in the championship. On the other hand, teams that compete for goals such as access to European competitions will tend to be under greater pressure from other teams that traditionally compete for the same positions. Thus, we also include in our analysis the total budget per point of the last season’s neighbours and manager changes among neighbour teams over the previous five matchdays (Bruinshoofd and Weel Citation2003). We consider neighbouring teams to be the two teams closest to a given team (above and below) in the final classification of the previous season of the national championship/league.

The third line of analysis – the analysis of the coach’s personal dimensions – draws on diverse contributions from psychology, sports sciences and even economics and sports management. These works show how the personal and curricular characteristics of a coach can influence his or her contractual duration. For example, accumulated fatigue – in the coach and/or the club’s directors – is expected when the contractual relationship has lasted over many matches (Foroughi et al. Citation2018), regardless of the success achieved. Coaches’ age (Frick, Pietzner, and Prinz Citation2007), foreign nationality (Gilfix, Meyerson, and Addona Citation2020), or interim/provisional contractual status (Tezcan Citation2013) can contribute to this fatigue. By definition, interim managers’ exit is usually predetermined, as they tend to last only a few games. However, we think this characteristic should not be neglected. Instead, a trail of successes individually achieved (Audas, Dobson, and Goddard Citation2008) – in particular in the hiring club (Tozetto et al. Citation2019) – tends to project an image of a winner and delay the end of the contractual relationship with the club.

There are some additional indicators of this dimension that should be considered. We refer to two in particular – the career leap (Gilfix, Meyerson, and Addona Citation2020) and disposability. The first indicator is inspired by the work of Gilfix, Meyerson, and Addona (Citation2020). This indicator analyzes the possibility of a coach being promoted (for example, the coach of a B-team or youth team becoming the coach of a major team or receiving an invitation from a club with a higher asset value that is interested in the trail of recent victories associated with that coach). The second indicator measures the number of dismissals suffered by a coach throughout his or her career (Kahn Citation2004). Given the linear relationship with age (coaches with more years of experience can be expected to have higher cumulative dismissals), we use the ratio between the number of cumulative dismissals and the coach’s age.

The fourth dimension of analysis that past studies identify as affecting the contractual longevity of sports team coaches is (recent) team performance. Conventional wisdom holds that the dismissal of the coach is the ‘lesser evil’ or ‘necessary sacrifice’ required to improve a team’s performance when it falls below (or significantly below) the club directors’ and supporters’ expectations. Works that detail this assumption include that of Oberhofer, Philippovich, and Winner (Citation2012).

In this context, if a football team concedes numerous goals (either in the most recent rounds or on average throughout the championship), it tends to be unable to compensate by scoring multiple goals in individual matches and therefore cannot accumulate enough points to achieve the expected league position. Some authors have focused on this source of pressure, including Galdino, Wicker, and Soebbing (Citation2020). Other works underscore the most recent matchdays as especially decisive for a coach’s continuity. Thus, poor performance in the most recent rounds – especially over a month (which includes between 4 and 5 games of a national championship, on average) – tends to result in the departure/firing of a coach. In addition to conceded goals, authors such as Addona and Kind (Citation2014) refer to the importance of defeats and low values on certain efficiency indicators (namely, the number of points scored per match and deterioration in this indicator over the previous month).

A team’s own current position (in terms of either rank order or number of points) relative to that in the previous season can exert additional pressure on the coach’s continuity. If a given team on the 15th matchday of a given season occupies the 10th position of the table when, in the previous season, it occupied the 5th position in the same matchday, we can conclude that it is performing worse in the current season. Such comparisons weaken arguments in favour of coach continuity, as reinforced by Audas, Dobson, and Goddard (Citation2008).

For this fourth dimension, our analysis identifies two more subdimensions. On the one hand, management of a team’s competitive cycle has been measured by the number of matchdays to the end of the championship. Thus, we include this indicator and its squared value to study nonlinear relationships (as there may be a nonlinear trend between the risk of dismissal and number of matchdays elapsed, as proposed by Martinez Citation2012). Another subdimension to take into account is the number of initial sporting objectives that have been eliminated for the team. This dimension relates to the notion that a greater number of competitions that a team participates in increases its coach’s probability of continuity on a given matchday; on the other hand, if all initial goals are already impossible to achieve in the current season, the risk of coach replacement increases (Horrillo and Forrest Citation2007; Heuer et al. Citation2011).

We assume that each soccer team adopts a strategy of minimizing average cost and that its coach’s fate hangs on this kind of (in)efficiency. Alternatively, we could consider a marginal cost variable in place of or together with average cost. For instance, we could compute the ratio between the variation in a team’s total budget (over a lapse of time) and that in the number of points gained in the championship table (over the same time). Then, a comparison of the team’s marginal cost with its marginal revenue (budget) would provide a certain kind of optimality condition as a benchmark for when a coach should be sacked (or not). However, in this work, we consider the initial budget for a given team as a fixed amount. Most of these clubs have to officially report their teams’ budgets, which are also communicated to the regulator (UEFA). Any change in this budget can be made only after complex procedures (securing board approval, holding general meeting discussions involving all affiliated members, etc.). Finally, UEFA has the final word on this issue (recall the Fair Play regulation in this respect). Because of this complexity, the large majority of these clubs maintain their initial team budget as a fixed amount that must produce the most efficient outcomes, whether sporting or financial. For this reason, and considering the pertinence of the recent track of a team’s sporting outcomes (a ‘proxy’ for the denominator in the ratio between the variation in a team’s total budget over a certain time and that in the number of points won in the championship table over the same period), we use several variables related to recent team performance that have already been discussed.

The fifth dimension is related to the endogeneity of sports directors. As Elaad, Jelnov, and Kantor (Citation2017) note, some governing bodies of soccer clubs have less patience than others. Thus, many previous coach dismissals by a club board signal a greater risk of future dismissal for a given coach should his or her results fall below expectations.

Finally, the sixth dimension identifies the importance of looking at each league’s competitive environment autonomously. As Carmo (Citation2010) points out, leagues such as the Portuguese one have historically tended to offer more unstable contractual relationships with coaches in charge of senior professional teams than other leagues. Thus, it is always useful to study the differences across championships in our empirical modelling.

III. Methodology and empirical analysis

In this study, the event of interest for each coach is the recurrence of dismissals from professional football teams. The time variable is the number of league matchdays until the occurrence of each dismissal for each coach. We also consider the possibility of having censored observations that represent cases with no dismissals in a season. We classify coaches who survive season t as censored for season t; therefore, at the start of the season, these observations are left-truncated if they were at risk before the period of analysis.

There are three main methods of analysing recurrent event data (Ghilotti and Bellocco Citation2018; Sagara et al. Citation2014): logistic regression models, count data models (Poisson and negative binomial), and traditional Cox models. In the case of logistic regression, binary outcomes indicate whether the event (for instance, a manager’s dismissal or quitting) was observed. In these cases, the time to the event is neglected, and in the simplest formats, all events occurring after the ending time are not considered. Count data models – namely, Poisson and negative binomial data – use a different strategy. These models tend to consider a total number of events for a time unit, with the time between repeated events simplified or nullified. Finally, traditional Cox models consider the time to the first event only, and all events occurring after the first important one are not analysed. These methods are not efficient or appropriate for discussing our data, where several losses commonly occur before a manager’s dismissal or quitting.

There are additional issues that must be considered in the discussion. These relate to whether the order of the event matters or whether the risk of recurrent events changes as the number of previous events increases. We must also pay attention to any differentiation between the overall effect or any specific effect coming from the k-th event and to whether there are significant recurrences by subject. These issues cannot be neglected when discussing coaches’ survival. Several papers have highlighted how the time of dismissal matters (Adona and Kind Citation2011) and even how the accumulated number of dismissals is not independent of the risk of dismissal Kahn (Citation2004). Therefore, extensions of the traditional Cox model have been developed into the following (Ghilotti and Bellocco Citation2018):

- The Andersen – Gill model;

- The Prentice, Williams and Peterson total time (PWP-TT) model; and

− Frailty models.

The Andersen – Gill model is used when a study focuses on the overall effect of a covariate on the hazard of a recurrent event. Following Ghilotti and Bellocco (Citation2018), this model is often used for frequent events. As a primary assumption, in this model, the risk of recurrent events remains constant regardless of the number of previous events.

Let us start from the Cox model (EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) ):

EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) shows that with n managers being studied, the hazard rate (the probability of remaining in charge of a team after t periods, or

) depends on the vector of the considered variables (x), the vector of the regression coefficients (

), and the baseline hazard (

) or the probability of being in charge when all of the explanatory variables are equal to 0. The Andersen – Gill model introduces a relevant change because it focuses on the hazard function for the k-th event of the i-th individual (EquationEquation 4

(4)

(4) ).

Following Ghilotti and Bellocco (Citation2018), EquationEquation 4(4)

(4) is a simple extension of EquationEquation 1

(1)

(1) that can be estimated with robust standard errors to account for correlation. EquationEquation 4

(4)

(4) also assumes that all failure types are unordered and that individuals contribute to the risk set for an event as long as they are observed at the time that the event occurs.

As an alternative, we have the PWP-TT model. This model, as suggested by EquationEquation 4(4)

(4) , is used when the effects of covariates may be differentiated across different events. As Ghilotti and Bellocco (Citation2018) also note, this is an appropriate choice when the accumulated number of prior events increases the probability of subsequent events or when there are few recurrences.

The PWP approach assumes that all individuals are expected to be at risk in the first stratum but that those with an occurrence in the first stratum can be at higher risk in the second stratum and so on. EquationEquation 4(4)

(4) allows the estimation of overall and event-specific effects and allows robust standard errors to account for correlation.

Frailty models can be synthesized by EquationEquation 4(4)

(4) :

In EquationEquation 4(4)

(4) ,

identifies the random effect associated with the excess risk or frailty of different individuals. Therefore, we recognize that the random effect may vary across individuals and be assumed to be constant over time for each individual. Additionally, it is also assumed that the baseline hazard model does not vary by event, as the event order is not taken into account. Frailty models are often analysed when each individual has his or her own specific exposure to the risk of recurrent events. Considering our case, these models offer additional insights because we must recognize that different managers express different responses after losing matches (Carmo Citation2010).

For model selection, several statistics are available and are discussed below. The most common and widely discussed are the log-likelihood, Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC), which appear in the tables with our estimations. Additionally, the mean square error (MSE), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAPE) are useful in complementing the discussion regarding the most appropriate model (these statistics are presented if required).

Data and descriptive analysis

The original database includes 598 coaches and 1074 cases of coach dismissal/change occurring in all clubs in the 6 European professional leagues between the 2009/2010 and 2019/2020 seasons. Although there are currently several websites with available information (transfermarkt.com, wikipedia.com, etc.), our work is based on official information from the clubs in question.

Our event of interest is each coach’s dismissal as a recurrent event. Coaches are censored at the time of attrition during follow-up or at the end of the study. The subjects were tracked for the time that they worked for the contracting European clubs. The covariates are those identified from the related six branches of the literature. shows the descriptive statistics of our variables.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

IV. Results

The main results are shown in . The German league is the reference group.

Table 2. Overall estimations (dismissal recurrence in 6 European major leagues, 2009/2010–2019/2020).

In general, the specific variables from each of the branches of the reviewed literature help explain the higher recurrence of coach dismissals. There is no single specifically validated stream from this literature, as none of the groups of variables show a disproportionate number of significant estimated coefficients. Thus, we can identify the following:

- From the perspective of financial issues, namely, average cost (total budget divided by points), an increase in the cost per point obtained in national championships and in the cost per goal scored tend to reduce a coach’s contractual longevity.

- Considering comparative pressure, a deterioration in the performance of neighbour teams from the previous season is associated with a lower recurrence of coach dismissal.

- Regarding coach individual characteristics, the risk of a coach’s departure is increased by the possibility of him or her being transferred to a club in a higher division or with a higher budget than the current club.

− In relation to the team’s sporting performance, an increase in the percentage of defeats in the last 10 games increases the risk of the coach leaving. On the other hand, the distance – measured as the number of matchdays – to the end of the national championship has a nonlinear relationship with the risk of the coach leaving. As we note below, there is a critical period, estimated at approximately the first 12 to 14 rounds of the championship, in which a coach faces a greater dismissal risk, which tends to decrease as the championship progresses.

- In the managerial dimension, we did not find statistically significant coefficients that allow us to validate whether boards with a longer history of coach dismissals have higher future recurrence of dismissals.

- Finally, considering the championship fixed effects, the Spanish and Italian leagues have a lower risk of premature departures by coaches, with all other variables held constant.

To interpret the estimated coefficients in , we use the estimated coefficient of 0.033 for the total budget per point variable in the frailty model (specifically, a Weibull Frailty model with a gamma distribution; see column 2) as follows:

- The risk of a coach suffering a recurrent dismissal increases exp (0.033)-1 = 3.05% with an increase in the relative cost of points by 1 unit. This means that a manager who has a total budget per point of 2000 has a 3.05% greater risk of being dismissed (hazard ratio) than another manager who has a total budget per point of 1000.

For a significant coefficient with a negative value, the interpretation is similar. For example, for the variable ‘Nr of team competitions at 5 matchdays before quitting’, we have an estimated value of −0.155 in the Weibull frailty model. Thus, the risk of a coach being released decreases by exp (−0.155)-1=−14.5% when the team was in another competition 5 rounds ago. Therefore, to preserve their place and avoid another dismissal in their career, our results suggest that coaches stand to gain if they can manage to keep the coached team in more competitions throughout the competitive season.

Now, let us detail the results considering the six streams of discussion on the professional longevity of a coach in each club observed over the seasons.

For the research focused on the cost of points and financial issues, we recognize the relevance of this dimension for the professional survival of a football coach. On the one hand, the main hypothesis analysed in this stream is that an increase in the cost of points obtained throughout the national championship, measured by the total budget per point, increases the dismissal risk. We recall that this view converges with the views of Stigler (Citation1958) and Frank (Citation1998) for firms/productive units. However, we do not validate that this relationship is nonlinear, as the square of the budget per point does not return statistically significant coefficients. Nor do we validate a role of additional pressure on teams with larger budgets or with higher received or paid transfer amounts. However, it is important to note that there is a tendency for the cost per goal to reduce the dismissal recurrence risk. This indicator tends to be stronger in teams with a higher proportion of draws (Calster, Smits, and Huffel Citation2008). These teams tend to score less but also to concede fewer goals; this evidence converges with the evidence found for the variable total budget per point.

For the neighbouring teams dimension, other comments emerge. Interestingly, the increase in the cost of points for teams traditionally neighbouring a given team reduces the risk of dismissal of the focal team’s coach. This dimension converges with Bruinshoofd and Weel’s (Citation2003) proposal that a competitive deterioration among teams in the neighbourhood works as a guarantee of additional longevity for the coach in charge of the focal team. On the other hand, in general, we do not find support for the hypothesis of contagion from observing psychological whiplash in traditionally neighbouring clubs: the estimated coefficients for a managerial change within neighbouring teams are not statistically significant in .

Let us now comment on manager characteristics. For the various observables, we find statistically significant coefficients only for the manager’s number of titles in the club and manager career upgrade in some of the estimation models. Thus, our estimates do not support the hypotheses that the coach’s record (beyond what he or she achieved at the club in question) or factors such as age or nationality are dimensions that influence the coach’s professional survival.

Regarding the team’s sporting performance, deserves some insights. Despite testing a diverse set of hypotheses posited in the literature, we find that only very few associated variables have statistically significant coefficients. We specifically refer to the variables ‘winning (%) the last 10 matches’, ‘matchdays to the end of the season’, ‘square of matchdays to the end of the season’, and ‘number of competitions in the team’s 5 matchdays before dismissal/quitting’.

Regarding the number of rounds remaining until the end of the championship, we verify a U-shaped nonlinear relationship. Considering the estimated coefficients for the Weibull frailty model, we find that 0.179J^2–2.475J is null when J = 2.475/(2 × 0.179) = 13.86 approximately. Thus, a coach’s risk of dismissal recurrence decreases up to approximately round 14 and then increases from this matchday onward.

Finally, for the dimension of team sports performance, we observe that keeping up in various competitions, even though it is a source of fatigue for players, tends to work as good professional longevity insurance for coaches. According to our estimates, between two observed coaches, the one with the team participating in the most competitions has a lower dismissal risk (−15% less for each competition in which the team played in the 5 rounds before dismissal).

In , we also estimate championship fixed effects in the specification of EquationEquation 4(4)

(4) , EquationEquation 4

(4)

(4) and EquationEquation 4

(4)

(4) . Some leagues present a lower risk of coach dismissal than the German league (the reference league), when the other variables remain constant. Thus, the Spanish, Italian and French leagues show a longer average duration over which coaches remain at the helm of a team.

detail the estimates for EquationEquation 4(4)

(4) , EquationEquation 4

(4)

(4) and EquationEquation 4

(4)

(4) for each championship separately. In general, there is a convergence between the results in these tables and those listed in .

Table 3. German league estimations (dismissal recurrence in the major league, 2009/2010–2019/2020).

Table 4. Spanish league estimations (dismissal recurrence in the major league, 2009/2010–2019/2020).

Table 5. French league estimations (dismissal recurrence in the major league, 2009/2010–2019/2020).

Table 6. English league estimations (dismissal recurrence in the major league, 2009/2010–2019/2020).

Table 7. Italian league estimations (dismissal recurrence in the major league, 2009/2010–2019/2020).

Table 8. Portuguese league estimations (dismissal recurrence in the major league, 2009/2010–2019/2020).

Some variables, however, have statistically significant coefficients for specific championships. For example, in addition to overall effects of the dimensions identified in on the contract duration of the observed coaches, coaches who work in German clubs have other dimensions to manage. Among these (see ), we highlight the weight of transfers paid by the club (the higher the paid transfers are, the lower the relative risk of the recurrent dismissal of the coach) or recognition of past victories, measured by the number of national titles achieved. However, numerous dismissals weighted by the age of the coach also act as a risk factor (thus, in the German case, young coaches with a short previous average duration in the clubs with which they have worked constitute a risk group). Note also that individual factors, as implied by the term ‘frailty’, play a preponderant role (in particular, log? is estimated to be statistically significant at 1%).

In the case of the Spanish league (), a few variables can explain coaches’ periods of work with respective teams. In addition to the number of matchdays elapsed, it is interesting to observe the estimated coefficient for the value of the three most expensive transfers received by the club – the higher this value is, the greater the reduction in the coach’s dismissal risk. This value is in line with that found by Rohde and Breuer (Citation2016).

Evidence for the French league is provided in . We highlight the weight of age as limiting the competitive survival of coaches. Our results, in line with those of Frick, Pietzner, and Prinz (Citation2007), suggest that an older coach has a higher relative risk of dismissal. Also noteworthy is the estimated coefficient for the variable associated with the different number of coaches hired by a given club board: the more coaches a board has hired in the past, the greater the relative risk of coach dismissal in the French championship.

presents observations for coaches who worked in the English Premier League in the periods in question. presents observations for coaches who worked in the Italian league (Serie A) in the same period. Regarding these two tables, we have three comments. The first concerns the few statistically significant coefficients in , which shows how, in line with the results in Audas, Dobson, and Goddard (Citation2008), a few specific factors operate in the contractual longevity of a ‘manager’ in England. Similarly, a U-shaped relationship is found between the dismissal risk and the number of matchdays to the end of the championship, indicating higher relative dismissal risks at the beginning and end of the Premier League editions (in contrast to the inverted-U shape for the remaining European leagues). For the Italian Serie A, more variables show statistically significant coefficients. Among them, we highlight age and the number of defeats among the last 10 games, once again identified as risk factors for coach dismissal in Italy.

Finally, highlights the results obtained for the Liga Portugal. Here, the cost per point obtained in the national championships also impacts the capacity of each coach to maintain his or her contractual relationship. Conceding many goals and having a significant number of defeats in recent matches reduce the contractual longevity of a coach working in the Portuguese league. Interestingly, for this league, a negative relationship is found between the accumulated number of coach dismissals in the main team and the risk of the current coach’s dismissal, revealing a tendency to be explored in future works whereby boards tend to have more dismissals at the start of the directors’ own tenure.

V. Conclusions and future work

The professional longevity of a professional football coach was analysed here for the 2009/2010 to 2019/2020 seasons across 6 European leagues. Although a significant body of work is emerging on the dismissal/professional survival of coaches, the current work originally explored average cost as an important determinant of this outcome.

Professional football coaches are highly qualified professionals whose contractual duration is exposed to the cycle of sporting results achieved by their teams. The literature on the subject has shown how economic-financial, individual and competitive dimensions intervene to explain the differentiated abilities of coaches to survive in such environments.

Using appropriate empirical methods to analyse coach survival in the face of recurring defeats, we conclude that there is a reduction in a coach’s probability of surviving additional matchdays for teams with higher average costs. Thus, if the average cost per point is high, a coach is more likely to be fired. We also explore a wide range of factors proposed in the literature – from the individual characteristics of each coach to the relative success of neighbouring teams – and discuss additional insights. Complementarily, we discuss these dimensions for each of the six professional leagues observed.

As emerging research avenues, we cite five proposals. The first proposal refers to the possibility of expanding the observed sample to include as many professional football leagues as possible. The second proposal, taking advantage of Stigler’s (Citation1958) microeconomic theory, is to try to observe the mimicry of budgets – above all of budgets by point or victory – to detail the most sustainable financial scales for the European clubs. The third proposal concerns the possibility of studying secondary leagues to detail the main differences in the estimated coefficients for the different variables tested as determinants of the professional survival of soccer coaches. Fourth, we highlight the possibility of recurring to additional variables (as data sources allow), such as the ratio between the variation in a team’s total budget over a span of time and that in the number of points gained in the championship table over the same span. Finally, the last proposal relates to the potential consideration of covariates relative to expected performance (rather than actual performance), where expectations can be derived from betting odds, for instance. As coaches’ performance is also measured by their ability to fulfill initial expectations, we consider it interesting to further research the potential of these covariates.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Addona, D., and A. Kind. 2014. “Forced Manager Turnovers in English Soccer Leagues.” Journal of Sports Economics 15 (2, April): 150–179. doi:10.1177/1527002512447803.

- Adona, S., and A. Kind. 2011. “Forced Manager Turnovers in English Soccer Leagues: A Long-Term Perspective.” Journal of Sports Economics 15 (2): 150–179. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1966543.

- Audas, R., S. Dobson, and J. Goddard. 2008. “Team Performance and Managerial Change in the English Football League.” Economic Affairs 17 (3): 30–36. doi:10.1111/1468-0270.00039.

- Bernheim, D., and M. Whinston. 2013. Microeconomics. New York: McGraw-Hill Economics.

- Bruinshoofd, A., and B. Weel. 2003. “Manager to Go? Performance Dips Reconsidered with Evidence from Dutch Football.” European Journal of Operational Research 148 (2): 233–246. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(02)00680-X.

- Bryson, A., B. Buraimo, A. Farnell, and R. Simmons. 2021. “Time to Go? Head Coach Quits and Dismissals in Professional Football.” De Economist 169 (1): 81–105. doi:10.1007/s10645-020-09377-8.

- Calster, B., T. Smits, and S. Huffel. 2008. “The Curse of Scoreless Draws in Soccer: The Relationship with a Team’s Offensive, Defensive, and Overall Performance.” Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports 4 (1): 4. doi:10.2202/1559-0410.1089.

- Carmo, C. 2010. A solidão de um treinador. Lisboa: Esfera dos Livros.

- CORDEIRO, J., and T. SHAW. 2010. Ceo Survival and Industry Discretion: An Application of Agency and Job Matching Theories. Proceedings1–6, doi:10.5465/ambpp.2010.54501142.

- Dias, R., and N. Vidya. 2021. “A Review of Factors Considered by the Athletes on Accepting Their Sport Coaches.” International Journal of Management, Technology, and Social Sciences 321–329. doi:10.47992/IJMTS.2581.6012.0148.

- Dobson, S., and J. Goddard. 2011. The Economics of Football. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511973864.

- Elaad, G., A. Jelnov, and J. Kantor. 2017. “You Do Not Have to Succeed, Just Do Not Fail: When Do Soccer Coaches Get Fired?” Managerial and Decision Economics 39. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2751971.

- Ficken, D., B. Scales, J. Kerr, R. Fuller, J. Barlow, and B. Tompkins. 2021. Men’s Soccer Coaches. University of Pennsylvania.

- Foroughi, B., H. Gholipour, H. McDonald, and B. Jafarzadeh. 2018. “Does National Culture Influence the Turnover Frequency of National Football Coaches? A Macro-Level Analysis.” International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 13 (6): 174795411878749. doi:10.1177/1747954118787492.

- Frank, R. 1998. Microeconomics and Behaviour. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Frick, B. 2012. “Career Duration in Professional Football: The Case of German Soccer Referees.” The Oxford Handbook of Sports Economics: The Economics of Sports 1. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195387773.013.0025.

- Frick, B., C. Barros, and J. Passos. 2006. “Coaching for Survival: The Hazards of Head Coach Careers in the German “Bundesliga”.” Applied Economics 41. doi:10.1080/00036840701721455.

- Frick, B., G. Pietzner, and J. Prinz. 2007. “Career Duration in a Competitive Environment: The Labor Market for Soccer Players in Germany.” Eastern Economic Journal 33 (3): 429–442. doi:10.1057/eej.2007.34.

- Galdino, M., P. Wicker, and B. Soebbing. 2020. “Gambling with Leadership Succession in Brazilian Football: Head Coach Turnovers and Team Performance.” Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal 11 (3): 245–264. doi:10.1108/SBM-06-2020-0059.

- García-Mateo, P., A. J. Casimiro-Artés, A. J. Casimiro-Andújar, and F. García-Marcos. 2020. “Communication in Sport Coaching: Parameters and Scopes.” International Journal of Recent Advances in Multidisciplinary Research 7 (6): 5842–5847.

- Ghilotti, F., and R. Bellocco. 2018. Recurrent-Event Analysis with Stata: Methods and Applications. XV Italian Stata Users Group Meeting, Bologna, 2018 November 15.

- Gilfix, Z., J. Meyerson, and V. Addona. 2020. “Longevity Differences in the Tenures of American and Foreign Major League Soccer Managers.” Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports 16 (1): 17–26. doi:10.1515/jqas-2019-0048.

- Heuer, A., C. Müller, O. Rubner, N. Hagemann, and B. Strauss. 2011. “Usefulness of Dismissing and Changing the Coach in Professional Soccer.” PloS One 6 e17664. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017664.

- Horrillo, J., and D. Forrest. 2007. “Within-Season Dismissal of Football Coaches: Statistical Analysis of Causes and Consequences.” European Journal of Operational Research 181: 362–373. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2006.05.024.

- Kahn, L. 2004. “Race, Performance, Pay, and Retention Among National Basketball Association Head Coaches.” Journal of Sports Economics 7. doi:10.1177/1527002505276723.

- Koning, R. 2003. “An Econometric Evaluation of the Effect of Firing a Coach on Team Performance.” Applied Economics 35: 555–564. doi:10.1080/0003684022000015946.

- Lee, J. 2014. “Soccer Goal Distributions in K-League.” Journal of the Korean Data and Information Science Society 25: 1231–1239. doi:10.7465/jkdi.2014.25.6.1231.

- Lee, M., C. Park, and J. Nam. 2013. “Importance of Sport Emotional Intelligence on Sports Psychological Skills and Sports Emotion Among Athletes.” Journal of the Korean Data and Information Science Society 24. doi:10.7465/jkdi.2013.24.2.355.

- Martinez, J. 2012. “Changing a Coach, Guarantee the Win? Evidence in Basketball.” Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Fisica y del Deporte 12: 663–679.

- Marwat, N., Z.U.I. Syed, M. S. Luqman, and Irfanullah. 2021. “Effect of Competition Anxiety on Athletes Sports Performance: Implication for Coach.” Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews 9: 1460–1464. doi:10.18510/hssr.2021.93146.

- Mourao, P. 2012. “The Indebtedness of Portuguese Soccer Teams–Looking for Determinants.” Journal of Sports Sciences 30 (10): 1025–1035. doi:10.1080/02640414.2012.695085.

- Mourao, P. R. 2016. “Soccer Transfers, Team Efficiency and the Sports Cycle in the Most Valued European Soccer Leagues – Have European Soccer Teams Been Efficient in Trading Players?” Applied Economics 48 (56): 5513–5524. doi:10.1080/00036846.2016.1178851.

- Mourao, P. 2017. The Economics of Motorsports. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Oberhofer, H., T. Philippovich, and H. Winner. 2012. “Firm Survival in Professional Sports: Evidence from the German Football League.” Journal of Sports Economics 16. doi:10.1177/1527002512462582.

- Rohde, M., and C. Breuer. 2016. “Europe’s Elite Football: Financial Growth, Sporting Success, Transfer Investment, and Private Majority Investors.” International Journal of Financial Studies 4 (2): 12. doi:10.3390/ijfs4020012.

- Ruano, M., C. Peñas, G. López, Maite, S. Saiz, and A. Leicht. 2021. “Coach’s Replacement and Team Performance.” Biology of Sport 38 (4): 603–608. doi:10.5114/biolsport.2021.101600.

- Sagara, I., R. Giorgi, O. K. Doumbo, R. Piarroux, and J. Gaudart. 2014. “Modelling Recurrent Events: Comparison of Statistical Models with Continuous and Discontinuous Risk Intervals on Recurrent Malaria Episodes Data.” Malaria journal 13: 293. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-13-293.

- Silva, E. E. D., A. A. D. Santos, M. A. P. D. Silveira, and P. J. R. Mourão. 2020. “Eficiência Financeira, Atores e Interações: Um Estudo do Fluxo de Jogadores entre Clubes e as Equipes Semifinalistas de São Paulo em 2017.” Internext 15 (1): 88–103. doi:10.18568/internext.v15i1.538.

- Silvestre, J. 2011. UMA ANÁLISE ECONOMÉTRICA SOBRE O IMPACTO DE UMA MUDANÇA DE TREINADOR NO DESEMPENHO DESPORTIVO DE UMA EQUIPA DE FUTEBOL. Thesis. ISEG – Lisbon

- Stigler, G. J. 1958. “The Economies of Scale.” The Journal of Law & Economics 1: 54–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/724882.

- Taylor, B., and D. Garratt. 2010. The Professionalisation of Sports Coaching: Relations of Power, Resistance and Compliance 15. Sport, Education and Society. doi:10.1080/13573320903461103.

- Tezcan, H. 2013. Job Continuity of Interim Coaches in the NBA: Within Season Appointments Between 1967-1968 and 2011-2012 Seasons. Istanbul Technical University Working Paper.

- Tozetto, A., H. Carvalho, da Rosa, Rodolfo, G. Mendes, Felipe, W. Silva, J. Vieira, and M. Milistetd. 2019. “Coach Turnover in Top Professional Brazilian Football Championship: A Survival Analysis.” Frontiers in Psychology. doi:10.10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01246.

- Tyler, W., and M. Sheridan. 2020. Career Decision Making in CoachingCareer Decision Making in Coaching. Dan Gould and Cliff Mallett, Eds. Leeds: International Council for Coaching Excellence (ICCE).