Abstract

Natural disasters, neglect and demolition continually exacerbate the dire state of heritage in New Zealand. This research investigates existing knowledge on heritage conservation in New Zealand and explores contemporary methods of digital preservation. The research involved a survey study of 156 responses from industry professionals, community members, government officials and academics. It was analysed using Braun and Clark's thematic analysis to understand the risks and benefits of digital tools in heritage conservation. The findings are organized into themes, sub-themes and codes. The paper is presented in three parts: (1) a review of heritage digitalisation methods and existing regulatory frameworks in New Zealand; (2) survey results and (3) a discussion on perceptions of using digital tools for conservation. Despite varying perceptions, the benefits of digitalisation outweigh the drawbacks. Through solutions outlined by professionals in the country, this paper highlights the potential of digitalisation to enhance heritage conservation efforts.

Introduction

The issue of heritage conservation is increasingly gaining attention globally, across the industry and academic disciplines, brought forth by the changes in our climate (Boccardi Citation2015; DeSilvey Citation2017; Giliberto and Jackson Citation2022; Hosagrahar et al. Citation2016; Nocca Citation2017; Rahmi Citation2017; Shamout, Boarin, and Mannakkara Citation2020; Trillo et al. Citation2020; UNESCO Citation1972). Digital tools have steadily become necessary among practitioners (Angulo-Fornos and Castellano-Román Citation2020; Beltramo, Diara, and Rinaudo Citation2019; Fadli and Al Saeed Citation2019; Laing Citation2020; Marcoux and Leifeste Citation2022; Oostwegel et al. Citation2022; Paris, Rossi, and Cipriani Citation2022; Pocobelli et al. Citation2018; Reinoso-Gordo et al. Citation2018; Rocha et al. Citation2020; Yüksek and Sökmen Citation2021) in the built environment, including architects, engineers, consultants, government organizations, and clients – with each discipline having its own set of specialized tools and databases. From those that relate to actively designing and modelling to those that are predominantly for recording purposes, the use of digital tools in architecture is becoming more commonplace (Will Citation2022). Particularly in the case of recording existing heritage, the benefits of using digital tools are manifold (Bruzelius Citation2017; Camerlenghi and Schelbert Citation2018; Frommel, Gaiani, and Simone Citation2021; Huffman and Dundas Citation2020; Rahaman and Champion Citation2019), providing a high level of accuracy and efficiency. Increased attention has been paid to upskilling professionals and students globally towards using these tools (Marcoux and Leifeste Citation2022). Upon comparison with international codes of heritage conservation, New Zealand has yet to learn about the benefits digital recording methods offer for conserving the country’s tangible and intangible heritage (Aburamadan et al. Citation2021; Digital Heritage Australia Citationn.d.; Global Digital Heritage Citationn.d.; Library of Congress Citation2002; Giliberto Citation2021; Mérai et al. Citation2020; Osman Citation2018; Vecco Citation2010). Currently, requirements and expectations for digital recording in this country do not meet international conservation standards, including having a national centralized platform for managing heritage, such as UNESCO’s proposal of an online heritage platform (UNESCO Citation2023).

While some may argue that New Zealand has a short history as a fairly young country, this does not justify the lack of conservation, disparate existing legislation and a lack of synchronization and direction between different organizations that manage heritage (Besen, Boarin, and Haarhoff Citation2020; Hamilton and Jadresin Milic Citation2020). The increasing effects of natural disasters, in some cases brought on by climate change (Okilj et al. Citation2023), have led to the loss of a significant number of heritage buildings across the country and continue to do so (Hamilton and Jadresin Milic Citation2020; Ministry for Culture and Heritage Citation2018). Every year, many heritage buildings fall under threat, eventually leading to their loss (Wolfe Citation2013). While the issue of heritage is prevalent and known to professionals across the country, it seems to be an issue of less importance and, therefore, often overlooked (Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Citation1996).

Rather than allowing our existing heritage to fade away with time, the research seeks to investigate the level of use and methods of using digital tools in heritage conservation (Boardman and Bryan Citation2018) to overcome gaps in the implementation of digital recording methods and the effective interpretation of resulting information in New Zealand. The research addresses these issues in partnership with professionals in the industry, government, community, and academics – the four main stakeholder groups nationwide – representing their professional opinions on heritage digitalization. The paper is presented in three parts: (1) reviewing (a) heritage digitalization methods and (b) the existing regulatory framework surrounding heritage management in New Zealand; (2) presenting survey results carried out among 156 professionals nationwide and analyzed using the qualitative method; (3) discussing the varying perceptions towards proposing a solution for effectively using digital tools to conserve our built environment for the future.

Materials and methods

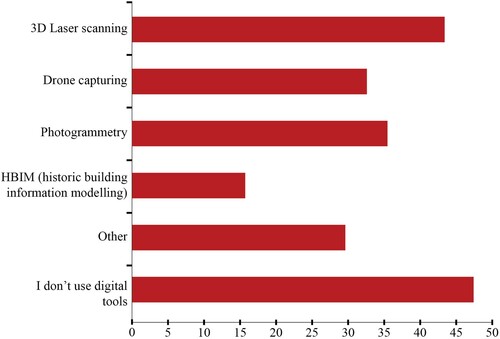

While the use of digital tools in architectural practice is routine during the design process (Rahaman and Champion Citation2019), documentation tools such as laser scanners and drones, combined with data from total stations to geo-reference, are less frequently used, due to the lack of understanding and expertise in operating these (Trillo et al. Citation2020). Given this complex dilemma, our study aims to understand the use of digital tools among professionals in the built environment in order to develop a theoretical framework that may help bridge the gap between current use and international practices. To address these aims, the study analyses the perception of digital heritage conservation among professionals in New Zealand through a nationwide survey. The research is primarily qualitative in nature, following Braun and Clark’s thematic analysis (Citation2022). This paper is primarily focused on the qualitative data collected, but some quantitative data is included in relation to demographics. The majority of qualitative data was manually coded in Excel and Quirkos. Before presenting the study, however, the theoretical background of digital conservation methods and regulations in New Zealand is explained.

Digitalization of heritage: tools, methods and existing framework

The use of digital tools is gaining traction across multiple disciplines, including heritage conservation (Milic et al. Citation2022; Trillo et al. Citation2020). The number of heritage sites and buildings incorporating digital recording methods such as laser scanning, drone scanning, photogrammetry, and historic building information modelling (HBIM) software are increasing globally (Bruzelius Citation2017; Rahaman and Champion Citation2019), as their impact on preserving heritage value is proven (Yüksek and Sökmen Citation2021). This literature review investigates the use of digital tools, their applicability and benefits in heritage conservation, while examining the existing regulatory framework in New Zealand to establish the context within which the stakeholders work.

Within the vast toolkit of a conservationist, architect, surveyor or engineer, digital tools such as laser scanners, drones, and photogrammetry supplement the surveying of existing heritage buildings and sites (Pocobelli et al. Citation2018; Rahaman and Champion Citation2019). Each tool contributes to preserving the heritage value of a building in a different way (Kontic, Jadresin Milic, and Mrljes Citation2019); some may be more useful during the documentation process, while others, such as HBIM, have uses throughout the project’s stages (Rahaman and Champion Citation2019). The information from digital tools is complementary and must be understood by architects, conservationists, surveyors, and engineers for the effective interpretation and use of information, as each tool has its benefits and uses depending on the state of the heritage project being captured (Fadli and Al Saeed Citation2019; Rahaman and Champion Citation2019; Rocha et al. Citation2020). Using digital tools can be particularly useful when recording heritage buildings that are under threat (Rahaman and Champion Citation2019), where traditional documentation may pose health and safety risks to those documenting (Kontic, Jadresin Milic, and Mrljes Citation2019). Instead, equipment such as drone scanners allows documentation to occur from a distance – without posing any risks to those scanning or the heritage building itself (Yüksek and Sökmen Citation2021). The advantages, disadvantages, and applicability of the digital tools mentioned in the survey are described in detail in Table .

Table 1. Digital tools comparison table.

While Table Footnote1 describes the applicability of digital tools, there are stages within the digital preservation process that contribute to the promotion of cultural heritage. These stages are identified as: (1) data collection on-site using digital tools; (2) data processing on software; (3) development of a 3D model and 2D drawings; (4) processing of visual material (renders and animations); and (5) data sharing and management among consultants for conservation, tourism, education, etc. It is important to develop the use of these methodologies in New Zealand, to ensure heritage value is encouraged and preserved for future generations.

Although digital tools offer tremendous benefits to the conservation process, their use is not implemented within the existing conservation framework in New Zealand, due to the lack of a centralized direction between the various organizations that manage heritage in the country (Historic Places Aotearoa & ICOMOS NZ, Citation2021). While heritage management in several developed countries falls under a centralized government organization, heritage management in New Zealand is fragmented across multiple frameworks (Besen, Boarin, and Haarhoff Citation2020; Hamilton and Jadresin Milic Citation2020). Namely, the Resource Management Act (RMA) 1991 and the Historic Places Act 1993 are the two core documents providing rules and regulations surrounding the protection and preservation of cultural and historical heritage (Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Citation1996). The RMA, however, was undergoing national policy changes (2021–2023) and was being replaced by two documents, the Natural and Built Environment Bill and the Spatial Planning Bill – a proposal to reform the inadequacy of the RMA in providing effective protection for the natural environment and cultural heritage (Natural and Built Environment Act 2023). In the review process, a recommendation by Historic Places Aotearoa and ICOMOS NZ (Citation2021) included wider incorporation of the use of digital tools and technology. Similarly, a contribution to the ICOMOS New Zealand charter practice notes and best practice guidelines scoping report (Smith Citation2021) recommends the use of digital tools in heritage conservation to preserve heritage value for future generations. These recommendations draw from a comparison with international standards to ensure New Zealand aligns better with global conservation practices. However, in December 2023, new legislation was passed to repeal the Natural and Built Environment Act and Spatial Planning Act. The government proposed the Fast-track Approvals Bill, with the purpose of providing ‘a streamlined decision-making process to facilitate the delivery of infrastructure and development projects with significant regional or national benefits’ (Parliamentary Counsel Office Citation2013). This recent change raises concerns about the implications for the effective ongoing management and protection of cultural heritage in New Zealand. We refer here to the weaknesses of the current standards and regulations that professionals are meant to adhere to, in order to show the context within which the survey participants are working.

Survey

The survey was developed by the researchers and Qualtrics was the data-collection tool. The survey consisted of 20 questions, 13 multiple choice and seven open ended, following the structure of: (1) a general understanding of the stakeholder’s relationship to digital heritage; (2) understanding their perceptions of the challenges and benefits of using digital tools; and (3) specific examples of which heritage buildings should be prioritized and why (Table ). Before taking part in the survey, all stakeholders were informed about the project and the confidentiality of their responses through the Information Sheet, after which they provided consent by starting the survey. Upon completion, quantitative reports and an Excel spreadsheet were downloaded from Qualtrics for qualitative analysis.

Table 2. Survey questions sent through Qualtrics.

Qualitative analysis

Responses to the 13 multiple-choice questions are presented in Figures and Table , providing quantitative data about stakeholder demographics. The responses to the seven open-ended questions, however, were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2022) reflexive thematic analysis and are described in the Results and Discussion sections. This flexible interpretative approach was used to identify and analyze patterns within the dataset (Braun and Clarke Citation2012; Citation2019; Citation2022) to understand the pressing issues professionals face regarding the use of digital tools when working with heritage buildings. This reflexive approach allows themes to emerge from the data, and its power to accommodate diverse theoretical perspectives was very suitable for our research. It engages and acknowledges the researcher’s influence on the interpretations of patterns of meaning across the dataset (Byrne Citation2022; Braun and Clarke Citation2019; Citation2022). Our research team consists of researchers with backgrounds in architecture, engineering, and cultural heritage. Our expertise in multiple fields allowed us to draw connections across disciplines. We were able to integrate architectural, engineering, and cultural knowledge and perspectives, which we believe has enriched our analysis and enhanced our ability to see themes and patterns in our qualitative data.

Table 3. Stakeholder demographics and responses.

In this study, we followed the six-phase process of thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (Citation2022): familiarization, coding, identifying and generating themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and writing up. The particular approach to thematic analysis used in the present study was reflexive and data driven. The data was open-coded manually without any pre-existing coding framework and consisted of a survey study of 156 responses from professionals in the industry, community, government, and academia across New Zealand.

The analysis began with the familiarization of data and then the generation of codes influenced by the researchers’ knowledge of the topic, which was subsequently adjusted for clarity and depth. The coding software Quirkos was used to define, map, and visualize the coded dataset. A group of researchers was involved throughout the coding process to ensure trustworthiness across the data. To ensure consistency in coding, the researchers discussed the coding decisions with each other throughout the process. This debriefing helped us identify potential biases and enhance the reliability of our codes.

The codes were examined and grouped into sub-themes to form patterns of meaning in the data, which were further grouped into broader themes, as presented in the Results section. The final stage involved an in-depth analysis and the creation of a narrative through the write-up process (Braun and Clarke Citation2012; Citation2022), describing the use of digital tools when working with heritage buildings in New Zealand, presented in the Results section.

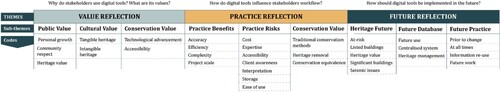

Initially, we conducted open coding, assigning codes to segments of text. Codes emerged from the data, capturing specific comments in the answers. We then grouped similar codes into potential themes and looked for patterns, repetitions, and variations across the dataset. For instance, codes related to ‘Accuracy’, ‘Efficiency’, ‘Complex Projects’, and ‘Project Scale’ were grouped under the sub-theme ‘Practice Benefits’. Similarly, codes related to ‘Cost’, ‘Expertise’, ‘Accessibility’, ‘Client Awareness’, ‘Info Translation’, ‘Storage’, and ‘Ease of Use’ were grouped under the sub-theme ‘Practice Risks’.

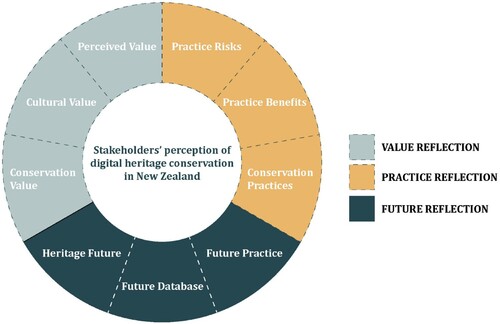

We reviewed the grouped sub-themes and themes, ensuring coherence and relevance; we also used iterative discussions among the researchers to refine the themes. Each sub-theme and theme received a descriptive name in this process. For example, sub-themes ‘Practice Benefits’ and ‘Practice Risks’, together with the sub-theme ‘Conservation Practices’, formed the theme ‘Practice Reflection’. Figure shows main codes, sub-themes and themes identified during the analysis.

Stakeholders

Understanding the perspectives of the experts in the field is critical to developing solutions necessary for heritage in New Zealand (Historic Places Aotearoa & ICOMOS New Zealand, Citation2021). The participants who responded to the survey are also among the beneficiaries of the future goals of the research and are therefore referred to as ‘stakeholders’ throughout the paper.

We distributed 2648 surveys via the Qualtrics platform, and 156 completed surveys formed our sample. This corresponds to an overall response rate of 5.9%. We calculated a margin of error of 8% at a 95% confidence level. When analyzing the data across different subgroups, we observed that the margin of error increased due to smaller sample sizes. Unlike selective sample sizes commonly used in focus groups and interview-based research, survey studies rely on the voluntary participation of interested individuals. In our case, we reached out to all 2648 known contacts to maximize responses. At a broad level, receiving 5.9% total response rate would estimate a general margin of error (at 95% confidence) of 8%. But given the skews shown in the survey responses, the quantitative results in the survey are indicative only, should be treated with caution and the focus should be put on the qualitative themes of the feedback. It is also important to note that our industry context is specific, and the responses primarily came from an engaged community – specifically, leaders in the digital heritage sector. When considering data for qualitative research, it is important to note data quality over quantity (Fugard and Potts Citation2019).

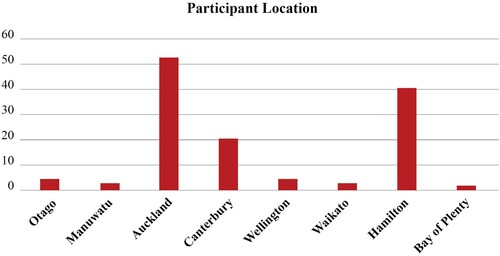

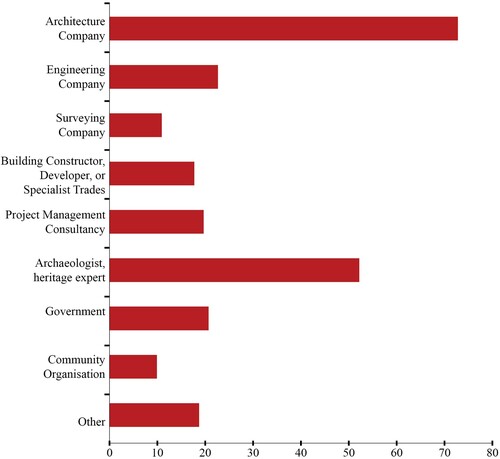

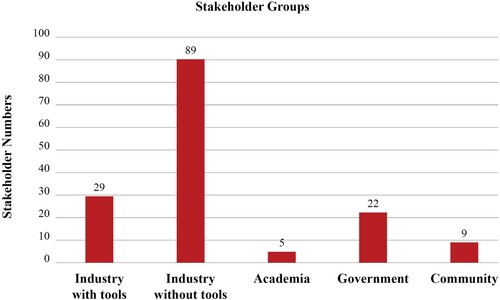

The sample size includes professionals across the country, as shown in Figure , ensuring a comprehensive dataset while reflecting the end-user types as presented in Figure . Stakeholders were grouped into four larger groups: (1) industry experts (118 stakeholders), (a) with digital tools (29 stakeholders), (b) without digital tools (89 stakeholders); (2) community representatives (9 stakeholders); (3) government representatives (22 stakeholders); and (4) academics (5 stakeholders). By categorizing the stakeholders within these four groups, we can better understand perceptions of digital tools based on the stakeholders’ relationship to heritage and their use of digital tools. The ethnic background and gender were not considered, as the study focused on expertise over demographic background.

Figure 4. Stakeholders sorted into four groups (note that Industry with and without tools comprise the single Industry group).

While Table portrays how one stakeholder may be associated with more than one field of expertise, sorting stakeholders into groups improves sample clustering, as shown in Figure . Regarding the use of digital tools by the stakeholders, the number of them operating the tools is displayed in Figures and . The stakeholder demographics presented in Table and in Figures are further analyzed in the results section.

While the quantitative aspects are essential for understanding response rates and margin of error, qualitative data based on open-ended questions remains central to this paper.

Results

The results have been identified as three main themes, reflecting the stakeholders’ perception of the digitalization of heritage: (1) Value Reflection, the perceived value of digital heritage; (2) Practice Reflection, the perceived influence of digital tools on current practice; and (3) Future Reflection, perception of future implications. Within each theme are three main sub-themes, as illustrated in Figure , under which numerous codes fall, holistically describing the perception, value and potential of digitalization of heritage. Each theme is presented in comparison to the existing practices and regulatory framework in New Zealand to describe the stakeholders’ perceptions based on their context.

Value reflection

The theme Value Reflection refers to why the stakeholders use digital tools, and the value they ascribe to them based on their professional experience. This theme encompasses three sub-themes: Public Value, Cultural Value, and Conservation Value. The theme of Value Reflection gives an understanding of the motivations and existing use of digital tools among professionals in New Zealand.

Public value

The sub-theme Public Value refers to the value the stakeholders recognize at an interpersonal scale, including personal growth, community respect, and heritage value.

Amidst the increasing use of digital technology across professions, a clear trend emerged: a growing preference for using digital tools for personal development and learning. Some participants come from a background of using traditional recording methods; one participant stated he ‘was trained in unmeasured drawings as an architect’ [Stakeholder 40] and is now seeking to learn new and contemporary methods to keep up with the times. Stakeholders are actively seeking to align their skills with national and international standards to address the lack of education on digital tools in New Zealand, stating that ‘Technology is the future. If you don’t adapt, you will fall behind’ [Stakeholder 21]. This effort aims to improve digital literacy, enhance professional capabilities, and drive innovation locally. Some observations include:

I am interested in becoming familiar with digital tools/technologies to advance my skillset as a heritage professional and to gain a deeper understanding of these tools’ current and potential future uses. [Stakeholder 31]

There is a lack of devices, attitude and skill set of staff. [Stakeholder 17]

Cultural value

The sub-theme of Cultural Value encompasses the intangible element of heritage preservation, reflecting stakeholders’ commitment to safeguarding New Zealand’s culture and history.

While acknowledging the uniqueness of local construction techniques and building typologies, stakeholders emphasised cultural and historical significance as the primary rationale for conservation efforts. Particular attention was noted to preserving the intangible heritage for future generations to connect with their roots, despite New Zealand’s relatively young age. It was argued by a stakeholder that the significance of preserving the nation’s tangible and intangible culture was of profound importance, given the increasing natural risks posed on places of cultural significance. Beyond cultural enrichment, this preservation effort holds potential advantages for the country’s tourism and hospitality industries.

Because these typologies are unique to our part of the world and are important heritage places. Due to the technology and materials used in constructing whare and wharenui, they can be fragile. They may not physically last long enough to admire [their] beauty for the next few generations. [Stakeholder 55]

Each has special characters which make them unique and part of our built history. [Stakeholder 30]

Once they are gone, a part of New Zealand’s history is gone. [Stakeholder 59]

Conservation value

The sub-theme of Conservation Value refers to the stakeholders’ perceptions of the significance of digital conservation methods.

Many stakeholders emphasised digitalization as a pivotal strategy for adapting to meet global technological advancements. Particular attention was observed on the significance placed on the upskilling of staff, emphasising that technology will continue to evolve over time, necessitating ongoing learning and adaptation to remain relevant and competitive. Some stakeholders emphasised the imperative of aligning with international standards, noting the current deficiency in this regard within New Zealand. This recognition underscores the importance of fostering a culture of innovation and continuous improvement to ensure that the country stays abreast of technological developments in heritage conservation.

Technology is the future. If you don’t adapt, you will fall behind. [Stakeholder 21]

It is largely accepted as an international recording standard and should be more accepted here when recording historic structures. [Stakeholder 68]

Practice reflection

The theme ‘Practice Reflection’ refers to the stakeholders’ reflections on digital tools in the workspace. This theme encompasses three sub-themes: Practice Benefits, Practice Risks, and Conservation Practices – reflecting on the perceived risks and benefits of using digital tools and highlighting anomalies in their perception.

Practice benefits

The sub-theme Practice Benefits refers to the benefits digital tools offer to the stakeholders for heritage conservation, including improved accuracy and detail, and workflow efficiency.

Among the many benefits highlighted by the stakeholders, accuracy and increased detail were identified as the most beneficial attributes. Unlike traditional recording, which relies on the skillset of an individual to correctly record the heritage asset, the digital record is often a direct capture of the heritage building or site, leading to a true reflection of the heritage asset. This is critical when documenting large or complex buildings, as accurate traditional recording takes more time and skill than digital recording.

Stakeholders highlighted efficiency as a significant benefit of digitalization, particularly in recording complex heritage sites. Digital tools enable the capture of inaccessible regions and intricate details of ‘complex decorative elements such as façades and irregular spaces’ with ease. This increased accessibility allows for integrated digital recording during site visits, reducing the need for multiple trips and mitigating travel-related challenges. Furthermore, converting physical assets to digital formats enhances accessibility, enabling remote access for clients and consultants regardless of geographical location. Generally, most stakeholders recognized and appreciated the value of digital tools to their practices, mentioning that:

the scanning has so many advantages there is almost no project we would not scan. [Stakeholder 17]

I think documentation is key to all kinds of work in heritage and it ought to be at least digital. [Stakeholder 17]

all sites visits should utilise one form of digital recording or another [Stakeholder 44]

Practice risks

While the benefits of digital tools have been identified as manifold, they equally have their challenges. The sub-theme Practice Risks refers to the stakeholders’ perceptions of the drawbacks of using digital tools, including cost, expertise, and client awareness.

The costs associated with operating digital tools were highlighted as a key contributor to the limited use among practitioners. In particular, it was noted that the costs required to maintain and renew software licences and subscriptions proved to be ‘prohibitive’ given that the tools were not used enough to provide ‘good value for investment’. Additionally, the costs associated with the storage and operation of the tools were equally challenging. Another cost issue is due to the large files requiring specific hardware that is not easily accessible to the majority, leading to the succeeding issue of a general lack of expertise. Some concerns over cost noted by the stakeholders include:

They are too expensive to purchase, too expensive to train people to use. [Stakeholder 89]

Cost, time to learn a new skill, and it needs to be useful for an actual project. [Stakeholder 65]

For our scale of work, they are not necessary, and cost more than they are worth. [Stakeholder 89]

Different companies using different tools/technologies, lack of clear methodology when multiple people work with the same information (changes aren’t always shared, and some people can be using outdated information). [Stakeholder 15]

I have had frustrations with some programs, ArchiCAD, Vectorworks, not doing what they are supposed to do even on the tutorials. I learnt on AutoCAD, & Revit did what it was supposed to do. A program that doesn’t do what it’s supposed to do not only makes you lose faith in the program but also makes the user feel useless in not being able to get the thing to work, affecting their confidence. [Stakeholder 19]

Incredible un-user-friendly programmes. Most programs claim ‘easy to use’ when it is, in fact, NOT. Worse of all – the COMPLETE lack of high-quality tutorials. Most are rubbish self-promoting users on you-tube where a world of timewasters prevails. [Stakeholder 40]

should be the first part of any project works, but it is often seen as expensive and unnecessary by clients. [Stakeholder 18]

Obviously digital recording would likely be beneficial to most projects, however, budget constraints from the client do not make it possible most of the time. [Stakeholder 50]

Client awareness – they don’t know what they are, and what they can do. [Stakeholder 32]

Conservation practices

The sub-theme Conservation Practices refers to the outlying responses reflecting the use of digital tools in practice. While the previous two sub-themes express the advantages and disadvantages of using digital tools, this sub-theme identifies the anomalies and concerns, including recording methodology, and heritage removal.

While a few stakeholders recognized the benefits of utilizing digital tools in their workflow, equally there were concerns about digitalization overshadowing traditional conservation methods. Stakeholders, particularly those accustomed to and proficient in traditional techniques, expressed reservations about the perceived complexity of digitalization. Their hesitance stemmed from a desire to maintain the efficacy of familiar, time-tested methods, citing concerns about potential confusion introduced by intricate digital tools. This perspective underscores the importance of striking a balance between embracing innovation and preserving established practices within the heritage conservation domain.

Devaluing the older recording forms when those techniques and systems should still retain value and respect. [Stakeholder 21]

I don’t think it’s fully appreciated by those introducing new regs and technologies how hard it is to do a full day’s work to pay the bills yet keep up with changes. [Stakeholder 52]

It’s more important to work at keeping our heritage, recording it just strikes me as an encouragement to dispose of them because they’ll be recorded. [Stakeholder 50]

Future reflection

The theme Future Reflection refers to the stakeholders’ perceptions of the future implementation of digital tools. This theme encompasses three sub-themes: Heritage Future, Future Database, and Future Practice. The theme Future Reflection presents changes and suggestions by stakeholders for conservation practice in New Zealand.

Heritage future

The sub-theme Heritage Future refers to the stakeholders’ proposals for mitigating New Zealand’s heritage loss. This sub-theme directly reflects existing issues, including national heritage loss, and prioritized sites.

With a notable surge in natural disasters nationwide, the proliferation of neglected heritage sites has become increasingly apparent. Stakeholders have voiced deep concern over the escalating loss of heritage due to natural decay and neglect, advocating for urgent intervention. Digital scanning is highlighted as a crucial tool for immediate preservation efforts to avert the permanent loss of significant sites. There is a strong consensus among stakeholders for prioritizing the conservation of buildings under threat of natural disasters, neglect, and demolition. Equal significance was noted on historically prominent buildings listed by Heritage New Zealand, given their legal recognition and inherent value to the nation. However, stakeholders also stressed the importance of extending preservation efforts to all heritage buildings, irrespective of their official designation. One stakeholder expressed profound concern for the protection of a specific heritage site currently facing imminent threats from natural hazards:

Edwin Fox is the last surviving mid-nineteenth-century East India trading vessel in the world. The vessel has significant historical connections with India, Britain, Crimea, Australia, and Aotearoa New Zealand, and was used for a variety of purposes, including shipping general cargo, troop carrying, transferring convicts, transporting immigrants and warehousing for the meat industry (1853–1900). The economic importance of exhibiting a historic ship at the Edwin Fox Maritime Museum is also recognised locally by the town of Picton and by the wider Marlborough region. Edwin Fox, however, is currently under threat from environmental processes. The hull sits in a dry dock supported by timber tongs and is therefore exposed to seismic activity. Earthquakes experienced in 2016 and continuing aftershocks felt in the Marlborough region threatened to destroy the vessel. Due to the vessel’s exposure to the unpredictable nature of earthquakes, it is at risk of being damaged beyond repair, resulting in the loss of important archaeological information and economic input for Picton. [Stakeholder 50]

The digitisation may become an invaluable record if the building was lost due to an earthquake, fire, etc. [Stakeholder 14]

Table 4. List of buildings and sites to be preserved, according to the stakeholders.

Future database

The sub-theme Future Database refers to the stakeholders’ proposals of how the digital assets may be used. It reflects on global digital heritage conservation standards, and policies, and identifies the stakeholders’ proposals for a more effective heritage management system in New Zealand.

The majority of stakeholders acknowledged the significance of digitalizing heritage buildings and contemplated the future use of this data. Great emphasis was noted on the absence of a centralized system in New Zealand for managing and organizing heritage assets, contrasting with centralized management systems in international practices. Currently, heritage data is dispersed across multiple locations in diverse formats, rendering it largely inaccessible to the wider community. Drawing inspiration from systems implemented overseas, such as in the UK and Italy, stakeholders proposed leveraging digital assets to establish an online database of heritage information. This initiative was argued to preserve the current state of buildings for future reference and enhance accessibility for industry professionals and the general public alike, thereby increasing engagement with heritage. Stakeholders contended that the most critical advantage of this approach would be:

to allow future generations to interact with the heritage asset in a virtual setting should it not exist physically [Stakeholder 60]

It is largely accepted as an international recording standard and should be more accepted here when recording historic structures. [Stakeholder 68]

Future practice

The sub-theme Future Practice encapsulates stakeholders’ perspectives on how digitalization can enhance the education sector and shape practitioners’ future approaches.

Stakeholders highlighted the critical utility of information obtained from scans for practitioners to learn about historic construction techniques and building methodologies. They emphasised that this information can be shared and applied seamlessly for conserving similar historic sites. Additionally, it was emphasised that the information has great potential for publication and educational purposes on better protection and effective conservation of heritage across the country. Stakeholders with an academic background noted the potential for further research towards ensuring consistent and effective heritage conservation practices, particularly significant for educating the next generation of architects.

methodology and procedures developed can be used in current and future projects and as reference. [Stakeholder 27]

Discussion

In response to the reflections illustrated in the Results, in the Discussion section the study aims to interpret the themes further and explore their implications, to understand the perception of digitalization by each stakeholder group in comparison with current rules and regulations, for a deeper understanding of the perceived risks and opportunities in New Zealand. Upon analyzing the 156 survey responses across the four stakeholder groups: (1) industry, (A) with digital tools and (B) without digital tools; (2) community; (3) government; and (4) academics, three key themes were identified. The themes are: (1) understanding the current use of digital tools among professionals; (2) understanding the risks and benefits of digital tools in practice; and (3) reflecting on their use in the future. Although the results illustrate the key findings as one group, the discussion expands on the details within each stakeholder group (Table ).

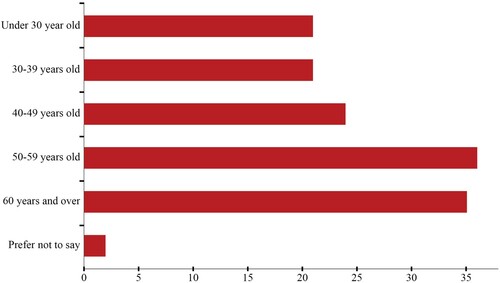

Table 5. Government stakeholders’ age groups as an influencing factor on their engagement with digital tools.

Industry

Among the industry stakeholders, the participants in Group A, who own and regularly operate digital tools, showed more recognition of their potential in the industry and vouch for their use to become common practice, meeting global technological advancement currently lacking in New Zealand. These trailblazing professionals are among the people who could encourage the use of digital tools to gain even greater traction across multiple disciplines, including heritage conservation, as referred to by Trillo et al. (Citation2020). However, the majority of participants in Group B, who do not have access to digital tools, saw less value in them, despite the fact that each tool could arguably contribute to preserving the heritage value of a building in a different way (Kontic, Jadresin Milic, and Mrljes Citation2019). While several countries globally have made digitalization a routine workflow in heritage conservation practices, New Zealand could learn from these examples (Besen, Boarin, and Haarhoff Citation2020) and discover the benefits digital recording methods offer for conserving a country’s tangible and intangible heritage (see Aburamadan et al. Citation2021; Giliberto Citation2021; Osman Citation2018; Digital Heritage Australia Citationn.d.; Global Digital Heritage Citationn.d.).

However, there are cases where some may value the information provided by digitalization but may not have access to it. The challenges noted by each group differed slightly: Group A perceived knowledge and expertise as the main challenges of digitalization, while Group B saw these as cost, expertise, and accessibility. Group A argued that while the majority might think that cost was the main challenge, the critical issue was the lack of knowledge on what digital tools offered and how to interpret the information for end use. Collectively, the industry group agreed that client awareness needed to increase for a greater value to be ascribed to digital tools. They also collectively appreciated the contribution of digitalization towards actively conserving a heritage building while providing learning opportunities for future projects.

While the perceptions of each group differed based on their use of digital tools, the constant challenge identified was the lack of knowledge, which can be traced back to the lack of regulations surrounding the use of digital tools in the existing framework. As seen in Besen, Boarin, and Haarhoff (Citation2020), and Hamilton and Jadresin Milic (Citation2020), heritage management in New Zealand is fragmented across multiple frameworks. Further research needs to raise awareness of the importance of heritage conservation, and therefore influence modifications of the existing legislation to address the lack of synchronization and direction between different organizations that manage heritage in New Zealand. Given that there are no rules regarding using digital tools, little is known about their benefits to preserving heritage. Currently, professionals in the industry are tasked with actively developing their skillsets based on emerging knowledge and technologies. However, knowledge about digitalization is not provided in professional development courses and existing frameworks, contrary to the global trend (Marcoux and Leifeste Citation2022). Consequently, the issue of the lack of knowledge continues. Therefore, the analysis expresses the importance of knowledge transmission, collaborative working environments, and implementing regulations to encourage the use of digital tools towards preserving our heritage in New Zealand.

Community

Although all community stakeholders in this study outsourced digital tools, a few participants recognized and valued the information and potential that digitalization offers. The challenges noted are similar to Group B’s, of cost, expertise and accessibility; however, they emphasised the challenge of making heritage more accessible to the public to encourage more heritage awareness and value. This could be especially useful in recording heritage buildings that are under threat or where traditional documentation may pose health and safety risks to those documenting (see Kontic, Jadresin Milic, and Mrljes Citation2019; Rahaman and Champion Citation2019). The accessibility issue is recorded as both a challenge and a potential for educating a wider audience, following a similar narrative in a recommendation made by ICOMOS New Zealand and Historic Places Aotearoa on reviewing the Resource Management Act (Historic Places Aotearoa & ICOMOS New Zealand, Citation2021). The recommendation stresses incorporating digitalization as part of heritage conservation, towards building a digital repository of heritage sites and buildings across New Zealand and, by doing so, preserving the country’s tangible and intangible heritage for future generations.

Government

Most stakeholders in the government group did not engage with digital tools as often as those in the industry group, due to the nature of their work. While their perceptions were based on their use of the tools, age was identified as a factor among those who did not recognize the tools’ potential. The younger stakeholders recognized the value of digital tools among government professionals, while the older professionals did not. A similar trend was observed among stakeholders who expressed concerns about replacing traditional working methods with digitalization. Among those who recognized the value and potential of digitalization, they emphasised its potential to meet international conservation standards such as UNESCO’s proposed online heritage platform (UNESCO Citation2023). As stated earlier, requirements and expectations for digital recording do not currently meet international conservation standards, including having a national centralized platform for managing heritage in New Zealand. The challenges of cost and availability were similar to the previous stakeholder groups; however, the critical finding from this group is the potential of digitalization for more effective national heritage management. The analysis of the government stakeholders’ perceptions shows little understanding of and attention towards the digitalization of heritage, which is apparent in the existing regulations.

Academics

Among the academics, a minority of participants owned and regularly used digital tools, while a few participants outsourced them. Those who recognized the value of digitalization described the tools’ potential to advance research and education, with the possibility of contributing towards a database for heritage management, as identified in the review of the RMA (Historic Places Aotearoa & ICOMOS New Zealand, Citation2021), or as technology becoming a positive contribution to the teaching curriculum (Milic et al. Citation2022). Although the minority of participants owned the tools, due to cost issues in many cases, they did not list accessibility as an issue, implying that with active collaboration with industry professionals who owned the tools, the accessibility issue might dissolve. As Jadresin Milic et al. (Citation2022) discuss, heritage projects require multidisciplinary collaboration among experts and specialists to inform the understanding of the value and significance of heritage as an asset. Decisions on future interventions, conservation and management have to be based on an understanding among professionals and decision makers, so the quality of information for this multidisciplinary knowledge can be used as an asset for heritage projects.

Concluding remarks

It is evident from our study that there are varied perceptions of the uses and benefits of digital tools for heritage conservation among the stakeholders surveyed. However, most across the four groups argued for heritage knowledge as the key driver for change, and digitalization to enhance and protect our built environments. Therefore, our survey findings can serve to progress towards a more thoughtful approach to conserving heritage through digital means. Although this study is among the first set of discussions with the country’s professionals, it has developed into further engagement through focus-group discussions (which are in the process of analysis) to create an environment of active critique and development across stakeholder groups. More importantly, the findings from the study contribute towards developing a digital portal, as stressed by many stakeholders, to improve heritage management in New Zealand while making heritage more accessible to the public. This would serve as a contemporary method of safeguarding the country’s history and culture for future generations to learn from.

One limitation of the current study and survey is the absence of stakeholders owning heritage buildings, or heritage trusts, which, in the future, can be included as the fifth stakeholder group. Although there are technological possibilities in the market for digital recording and preserving cultural heritage, the country needs clarification on a national strategy and standardized methodologies for digital documentation, preservation and presentation. These steps are necessary to make heritage accessible to all, to encourage active preservation of heritage and prevention of decay and neglect, to create a digital repository of information on New Zealand’s heritage buildings and sites, and to encourage a generation of architects to value and protect the intangible and tangible history of the country. It is necessary to involve representatives from the government, community, academia, industry, and cultural heritage experts to accomplish these goals. Through this synergy and contribution of individuals from different fields, it would be possible to strategise the digital preservation of cultural heritage.

Acknowledgements

This project received funding from the Unitec ECR funding 2021–22, grant code: RI20006/RE20003. The UNITEC Research Ethics Committee has approved the study. UREC REGISTRATION NUMBER: UREC 2022-1010 Milic. Start date 25 May 2022, finish date 25 May 2023. The authors would like to thank the project participants. We would also like to thank our home institution, Unitec, and especially the Tuapapa Rangahau Research Office for generously supporting us with the project.

Data availability statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Historic England (Citation2017a), BIM for heritage: Developing a Historic Building Information Model; Historic England (Citation2017b), Photogrammetric applications for cultural heritage: Guidance for good practice; Boardman and Bryan (Citation2018), 3D laser scanning for heritage: Advice and guidance on the use of laser scanning in archaeology and architecture.

References

- Aburamadan, R., C. Trillo, C. Udeaja, A. Moustaka, K. G. B. Awuah, and B. C. N. Makore. 2021. “Heritage Conservation and Digital Technologies in Jordan.” Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 22: e00197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.daach.2021.e00197.

- Angulo-Fornos, R., and M. Castellano-Román. 2020. “HBIM as Support of Preventive Conservation Actions in Heritage Architecture. Experience of the Renaissance Quadrant Façade of the Cathedral of Seville.” Applied Sciences 10 (7): 2428. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10072428.

- Beltramo, S., F. Diara, and F. Rinaudo. 2019. “Evaluation of an Integrative Approach between HBIM and Architecture History.” In Proceedings of the International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLII-2/W11. GEORES 2019 – 2nd International Conference of Geomatics and Restoration, Milan, Italy, 8–10 May 2019. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLII-2-W11-225-2019.

- Besen, P., P. Boarin, and E. Haarhoff. 2020. “Energy and Seismic Retrofit of Historic Buildings in New Zealand: Reflections on Current Policies and Practice.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 11 (1): 91–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2020.1715597.

- Boardman, C., and P. Bryan, eds. 2018. 3D Laser Scanning for Heritage. 3rd ed. Historic England. https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/3d-laser-scanning-heritage/

- Boccardi, G. 2015. “From Mitigation to Adaptation: A new Heritage Paradigm for the Anthropocene.” In Perceptions of Sustainability in Heritage Studies, 87–97. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110415278-008

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2012. “Thematic Analysis.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. Volume 2: Research Designs, edited by H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher, 57–71. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/thematic-analysis/book248481

- Bruzelius, C. 2017. “Digital Technologies and New Evidence in Architectural History.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 76 (4): 436–439. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26419043.

- Byrne, D. 2022. “A Worked Example of Braun and Clarke’s Approach to Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Quality & Quantity 56 (3): 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y.

- Camerlenghi, N., and G. Schelbert. 2018. “Learning from Rome: Making Sense of Complex Built Environments in the Digital Age.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 77 (3): 256–266. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2018.77.3.256.

- DeSilvey, C. 2017. Curated Decay. Heritage Beyond Saving. University of Minnesota Press. https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/curated-decay.

- Digital Heritage Australia. n.d. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.digitalheritageaustralia.com/.

- Fadli, F., and M. Al Saeed. 2019. “Digitizing Vanishing Architectural Heritage; The Design and Development of Qatar Historic Buildings Information Modeling [Q-HBIM] Platform.” Sustainability 11 (9): 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092501.

- Frommel, S., M. Gaiani, and G. Simone. 2021. “3-D Digital Modeling and Giuliano da Sangallo’s Designs for Santa Maria Delle Carceri in Prato.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 80 (1): 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2021.80.1.30.

- Fugard, A., and H. W. Potts. 2019. “Thematic Analysis.” In SAGE Research Methods Foundations, edited by P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J. W. Sakshaug, and R. A. Williams. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526421036858333

- Giliberto, F. 2021. “Using Digital Technologies to Innovate in Heritage Research, Policy and Practice.” Heritage and Our Sustainable Future 5. https://unesco.org.uk/using-digital-technology-to-innovate-in-heritage-research-policy-and-practice/.

- Giliberto, F., and Jackson, R., eds. 2022. Cultural Heritage in the Context of Disasters and Climate Change. A research report by PRAXIS: Arts and Humanities for Global Development and CRITICAL: Cultural Heritage Risk and Impact Tools for Integrated and Collaborative Learning. https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/193145/1/Cultural%20Heritage%20in%20the%20Context%20of%20Disasters%20and%20Climate%20Change%20%282%29.pdf

- Global Digital Heritage. n.d. Harnessing the Latest Technologies. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://globaldigitalheritage.org/.

- Hamilton, J., and R. Jadresin Milic. 2020. “Preservation Issues and Controversies: Challenges of Underutilised and Abandoned Places.” In Imaginable Futures: Design Thinking, and the Scientific Method, edited by A. Ghaffarianhoseini and N. Nasmith, 885–894. Auckland, New Zealand: 54th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association 2020, Auckland University of Technology. https://archscience.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/91-Preservation-issues-and-controversies-Challenges-of-underutilised-and-abandoned-places.pdf.

- Historic England. 2017a. BIM for Heritage: Developing a Historic Building Information Model. https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/technical-advice/recording-heritage/.

- Historic England. 2017b. Photogrammetric Applications for Cultural Heritage: Guidance for Good Practice. https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/photogrammetric-applications-for-cultural-heritage/.

- Historic Places Aotearoa & ICOMOS New Zealand. 2021. Submission to the Environment Committee Inquiry on the Natural and Built Environments Bill: Parliamentary Paper HPA / ICOMOS NZ JOINT SUBMISSION. Historic Places Aotearoa. https://historicplacesaotearoa.org.nz/assets/RMA-Exposure-Draft-HPA-ICOMOS-Joint-Submission-2021-08-04.pdf.

- Hosagrahar, J., J. Soule, L. Fusco Girard, and A. Potts. 2016. “Cultural Heritage, the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and the New Urban Agenda.” Bollettino Del Centro Calza Bini 16 (1): 37–54. https://doi.org/10.6092/2284-4732/4113.

- Huffman, K. L., and I. Dundas. 2020. “San Geminiano: A Ruby among Many Pearls.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 79 (1): 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2020.79.1.6.

- Kontic, A., R. Jadresin Milic, and R. Mrljes. 2019. “Defining the Methodology of Integrated Research in the Process of Digital Documentation of Architectural Heritage: Case Study Lizori, Italy.” Disegnarecon 12 (23): 2.1–2.11. https://doi.org/10.20365/disegnarecon.23.2019.2.

- Laing, R. 2020. “Built Heritage Modelling and Visualisation: The Potential to Engage with Issues of Heritage Value and Wider Participation.” Developments in the Built Environment 4: 100017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dibe.2020.100017.

- Library of Congress. 2002. Preserving Our Digital Heritage. Plan for the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program. https://www.digitalpreservation.gov/documents/ndiipp_plan.pdf.

- Marcoux, J., and A. Leifeste. 2022. “Impact of Digital Technologies on Historic Preservation Research at Multiple Scales.” Technology Architecture + Design 6 (1): 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/24751448.2022.2040299.

- Mérai, D., L. Veldpaus, M. Kip, V. Kulikov, and J. Pendlebury. 2020. Typology of Current Adaptive Heritage re-use Policies. Metropolitan Research Institute. https://openheritage.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Typology-of-current-adaptive-resue-policies.pdf.

- Milic, R. J., P. McPherson, G. McConchie, T. Reutlinger, and S. Singh. 2022. “Architectural History and Sustainable Architectural Heritage Education: Digitalisation of Heritage in New Zealand.” Sustainability 14 (24): 16432. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416432.

- Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 2018. Strengthening Protections for Heritage Buildings. Report Identifying Issues within New Zealand’s Heritage Protection System. https://www.mch.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2023-11/proactive-release-strengthening-protections-for-heritage-buildings-report.pdf.

- Nocca, F. 2017. “The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool.” Sustainability 9 (10): 1882. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101882.

- Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. 1996. Historic and Cultural Heritage Management in New Zealand. Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment: Te Kaitiaki Taiao a Te Whare Paremata. Accessed November 8, 2023. https://pce.parliament.nz/media/fn2mnoin/historic-and-cultural-heritage-management-in-new-zealand-june-1996-small.pdf.

- Okilj, U., M. Cvoro, S. Cvoro, and Z. Uljarevic. 2023. “The Green Dimension of a Compact City: Temperature Changes in the Urban Area of Banja Luka.” Buildings 13 (8): 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13081947.

- Oostwegel, L. J. N., Š. Jaud, S. Muhič, and K. M. Rebec. 2022. “Digitalization of Culturally Significant Buildings: Ensuring High-Quality Data Exchanges in the Heritage Domain Using OpenBIM.” Heritage Science 10), https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00640-y.

- Osman, K. A. A. 2018. “Heritage Conservation Management in Egypt: A Review of the Current and Proposed Situation to Amend It.” Ain Shams Engineering Journal 9 (4): 2907–2916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2018.10.002.

- Paris, L., M. L. Rossi, and G. Cipriani. 2022. “Modeling as a Critical Process of Knowledge: Survey of Buildings in a State of Ruin.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 11 (3): 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11030172.

- Parliamentary Counsel Office. 2013. Fast-track Approvals Bill. https://www.legislation.govt.nz/bill/government/2024/0031/latest/LMS943195.html?search=y_bill%40bill_2024__bc%40bcur_an%40bn%40rn_25_a&p=1.

- Pocobelli, D. P., J. Boehm, P. Bryan, J. Still, and J. Grau-Bové. 2018. “BIM for Heritage Science: A Review.” Heritage Science 6 (1): 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-018-0191-4.

- Rahaman, H., and E. Champion. 2019. “To 3D or not 3D: Choosing a Photogrammetry Workflow for Cultural Heritage Groups.” Heritage 2: 1835–1851. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2030112.

- Rahmi, D. H. 2017. “Building Resilience in Heritage District: Lesson Learned from Kotagede Yogyakarta Indonesia.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 99: 012006. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.10881755-1315/99/1/012006/pdf.

- Reinoso-Gordo, J. F., C. Rodríguez-Moreno, A. J. Gómez-Blanco, and C. León-Robles. 2018. “Cultural Heritage Conservation and Sustainability Based on Surveying and Modeling: The Case of the 14th Century Building Corral del Carbón (Granada, Spain).” Sustainability 10 (5): 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051370.

- Rocha, G., L. Mateus, J. Fernández, and V. Ferreira. 2020. “A Scan-to-BIM Methodology Applied to Heritage Buildings.” Heritage 3: 47–67. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage3010004.

- Shamout, S., P. Boarin, and S. Mannakkara. 2020. “Understanding Resilience in the Built Environment: Going Beyond Disaster Mitigation.” In The 54th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association 2020. Auckland University of Technology. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349521171_Understanding_resilience_in_the_built_environment_Going_beyond_disaster_mitigation

- Smith, M. 2021. ICOMOS New Zealand Charter Practice Notes and Best Practice Guidelines Scoping Report (Report No. 104). ICOMOS New Zealand. https://icomos.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ICOMOS-NZ-Charter-Practice-Notes-Scoping-Report-2021-FINAL-with-appendices.pdf.

- Trillo, C., R. Aburamadan, S. Mubaideen, D. Salameen, and B. C. N. Makore. 2020. “Towards a Systematic Approach to Digital Technologies for Heritage Conservation. Insights from Jordan.” Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture 49 (4): 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1515/pdtc-2020-0023.

- UNESCO. 1972. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. https://www.refworld.org/docid/4042287a4.html.

- UNESCO. 2023. World Heritage: Online Map Platform. https://whc.unesco.org/en/wh-gis/.

- Vecco, M. 2010. “A Definition of Cultural Heritage: From the Tangible to the Intangible.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 11 (3): 321–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2010.01.006.

- Will, R. L. 2022. “Digital Techniques in Historic Preservation.” Technology Architecture + Design 6 (1): 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/24751448.2022.2040298.

- Wolfe, R. 2013. New Zealand’s Lost Heritage: The Stories Behind our Forgotten Landmarks. Auckland: New Holland Publishers (NZ) Ltd.

- Yüksek, G., and S. Sökmen. 2021. Digital Cultural Heritage: Some Critical Reflections. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354208388_Digital_Cultural_Heritage_Some_Critical_Reflections.