This is the second to last of the issues I will have assembled during my term as editor of Art Education and I have two more conversations I would like to start. I have always been a big picture thinker. I often see larger patterns—for example, the undulating canopy of the forest—before the smaller ones become visible to me—like individual branching trees, rising from the earth. Likewise, it is apparent to most art + design educators that the arts are sorely undervalued in a society where the newly elected White House administration immediately proposed the end of federal arts funding and continues to press toward this goal. That's the forest we dwell in. But what is often overlooked in today's landscape is how varying the value of the arts can be for individual learners at different points in their education. Forests with more than one kind of tree tend to thrive.

Art is not just beauty. Some art is intentionally ugly, like the oeuvre produced by the rebellious, disaffected artists of the Dada art movement, who would often go so far as to make art out of trash or other refuse. Some art focuses our gaze on ugly things, like Picasso's monochromatic antiwar painting of the bombing of the small Basque province town of Guernica, relating the trauma of a Spanish Civil War atrocity through the lens of Cubism. Nor is art mere self-expression. Art expresses far more than just personal sense or significance—it generates new ideas and reinterprets status quo perceptions about identity, lived experience, religious and political beliefs, cultural practices, material properties, ancestral and social relationships, and even the natural affinity an artist or designer possesses for particular creative practices or techniques (CitationRolling, 2006).

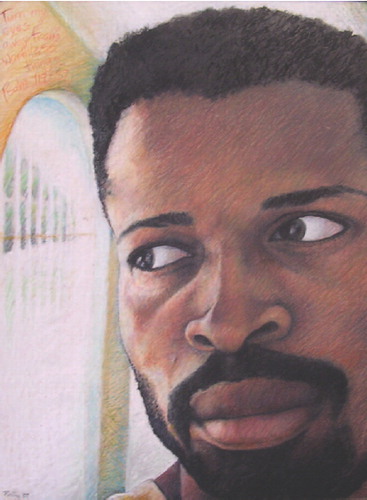

Art is evidently a many-splendored thing. Given that the landscape of art + design is not comprised of just one kind of tree, this issue of Art Education explores art as therapy. Once upon a time, when I was a young man, I asked a young woman to marry me. Although I met her while she was on an extended visit to the United States, I was both enamored and naïve enough to begin making plans to uproot my life and relocate to the Caribbean island where she lived. I found out shortly thereafter that this woman was in a relationship with another man and was stringing me along, unable to come clean and cut ties. I was more than devastated; I was lost. Unable to locate myself, unwilling to self-medicate, I had no other resource but to throw myself into the rendering of a self-portrait. Even though nothing made sense to me anymore, as an artist I knew I could make new sense. Make no mistake, art became my therapy—in this case, a color pencil portrait that for well over a week, perhaps two, was both my alchemy and my science. I worked non-stop during my waking hours, losing track of both time and sustenance as I tried to rescue my broken identity to a safe plateau on an unforgiving world map.

Art therapy “is based on the idea that the creative process of artmaking is healing and life enhancing and is a form of nonverbal communication of thoughts and feelings” that must be resolved in order to “achieve an increased sense of well-being” (CitationMalchiodi, 2003, p. 1). In an invited commentary, David Rufo shares a story from his elementary school classroom documenting how children are capable of self-initiating the creative process as a form of therapy to alleviate learning anxieties when acquiring skills in math or other subjects in which they are regularly assessed. Libba Willcox explores the role of vulnerability in the art room, arguing that teachers can better support student risk-taking by fostering environments for creative exploration that are also psychologically safe. Simone B. Alter-Muri offers vignettes from her experience as an art teacher and art therapist demonstrating the development of activities that both empower students experiencing Autism Spectrum Disorder and minimize distractions to meaning-making and expression in the art + design classroom. Lisa Kay and Denise Wolf encourage a collaborative approach to art + design pedagogy, building professional coalitions between educators and therapists to counter the trauma and stresses that often accompany adolescence.

Also in this issue,Margo Collier and Linney Wix establish an instructional paradigm of collaboration and care for both art + design education and special education teacher candidates in response to the conundrum of art teachers not knowing enough about inclusive teaching practices and special education teachers not knowing enough about teaching art—a content area that students with disabilities often show great affinity for. SeungYeon Lee relays some effective strategies and therapeutic activities for engaging and motivating inner-city students in afterschool art + design classrooms as a means of coping with daily life challenges and low self-esteem. By capitalizing on the innate sense of humor of exceptional students,Stephen Tornero and Koon Hwee Kan examine the effectiveness of using images from the surrounding visual culture in the inclusive art room. Finally, Sheng Kuan Chung and Dan Li present the playful and functional public sculptures of Hong Kong artist Tin Yan Wong as art for daily living.

Altogether, art as therapy is also art as a restorative practice that is sorely needed throughout schools and communities today.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

James Haywood Rolling

James Haywood Rolling Jr. is Dual Professor and Chair of Art Education in the School of Art/College of Visual and Performing Arts, and the Department of Teaching and Leadership/School of Education, Syracuse University, New York. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

Correction: In the July issue, the bridge depicted in Faith Ringgold's Tar Beach is the George Washington Bridge.

References

- Malchiodi, C. A. (Ed.) (2003). Handbook of art therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Rolling, J. H. (2006). Who is at the city gates? A surreptitious approach to curriculum-making in art education. Art Education, 59(6), 40–46.