Creativity has long been the battle cry of the arts in education. This started changing some time ago, and now almost everyone thinks creativity is a good idea. School mission statements embrace creative thinking. Economists consider creative industries key growth sectors of economies around the world. And more locally, public officials race to refashion once neglected urban landscapes into hip creative cities.

On the surface, the broad-based enthusiasm for creativity looks like a positive development. Yet the arts in schools are not necessarily seeing additional support. Just this summer, Carol, a K-8 art teacher, wrote on the National Art Education Association's digital forum, Collaborate, about her school's junior high art program that was cut due to shifting curricular priorities. Responses poured in from around the country. I personally was moved by the encouragement Carol received. It included words urging her not to lose sight of her own creative agency in this situation. The conversation that unfolded generated concrete strategies she could use to improvise.

Carol's story is just one example of how creative agency is fostered in art and design education. Agency commonly is defined as the capacity to reflect upon and direct one's own thoughts and actions. When we talk about creative activities, humans typically are given the starring role to play. A few examples help illustrate this:

Carlos chose the red marker, not the blue one.

Eve wishes to draw a boat using charcoal.

The Art II students complete their clay pieces today.

The tour group interpreted the photographs.

The red marker, charcoal, clay, and photographs—are cast as passive objects, mere things controlled and acted upon by people. Carlos, Eve, the Art II students, and the tour group are the sole agents of creative thought and action. Over the last few decades, developments in creativity studies suggest a need to reconsider such person-centered beliefs about what creativity is and how to generate more of it.

Social psychologist CitationVlad Glăveneau (2014) is one of my favorite writers on this topic. He and others (e.g., CitationClapp, 2017) say that creativity does not come from ideas inside a person's head, as many tests for creativity assume. Nor is creative agency exclusive to humans. Instead, creativity, or the making of something new, is a distributed phenomenon, which is to say it emerges from the interplay between a person and all the affordances found in one's context.

The distributed perspective says that context is integral to the creativity of artists, authors, students, and inventors because the efficacy of a person's creative agency is entangled with and dependent on the assistance (and sometimes resistance) of other elements external to the person. An good analogy is the way a constellation emerges in between stars and not by the power of one star alone. In much the same way, creativity emerges from the collaborative relationship between person and context and not from the creative person alone.

There are at least four elements of context that intervene to enable and constrain human creative agency (CitationGlăveneau, 2014). They are:

Social recognition and validation through feedback from an audience or other public. We might call this the co-creative power of people.

Material affordances of nonhuman things (for example, the color saturation and linear quality of Carlos's red and blue markers) that enable the human imagination to extend beyond the person and take form in the world. We might call this the co-creative power of things.

Cultural practices, symbols, and meanings that already exist collectively within a community and empower the creative person to reconfigure new practices, new symbols, and new meanings. We might call this the co-creative power of culture.

Historical development of creative practices over centuries and smaller increments of time (years, weeks, or minutes) that enable the person to imitate and learn skills, improvise with materials and methods, and develop new conventions. We might call this the co-creative power of time.

These contextual elements point to the importance of other people, things, culture, and time in any creative process.

Context enables and constrains the personal choices and possible outcomes of creative activity. As many art teachers know already, the structure and guidelines in an art project or design challenge are limits on creativity that simultaneously can provide a context that catalyzes learners' agency (CitationFendler & Hamrock, 2018; CitationGraham, 2009). Without any context or structure for artmaking, many students find themselves without ideas for how to begin. Context, therefore, plays a significant co-creative role in artistic and other creative processes, both limiting and extending what individuals can achieve on their own.

In situations in which there are excessive constraints—too little time and material support or outright suppression of creative agency—people nonetheless find ways to create with and within (and sometimes against!) the contextual limits imposed on their lives.

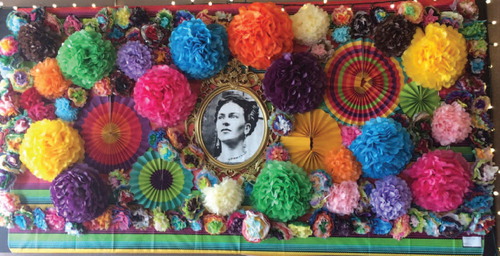

For instance, rasquachismo and hip-hop aesthetics emerged from Chicano and African American communities living under oppressive conditions in the United States (CitationBarnet-Sanchez, 2005; CitationCobb, 2007).Footnote1 Rasquache and hip-hop represent the art of making do, the practice of improvising with whatever elements are at hand. Artists appropriate cultural references and invent new uses for old or undervalued materials (including sometimes their own bodies). Each aesthetic has its own forms and styles of expression, but rasquachismo and hip-hop share an irreverence toward dominant cultural sensibilities, an attitude of spontaneity, a connectedness to the past, and a resistance to discriminatory policies and practices that have adversely affected communities of color over generations.

The articles in this issue of Art Education feature research and ideas about how art and design education fosters creative agency. In “Art Studio as Thinking Lab: Fostering Metacognition in Art Classrooms,” Julia Marshall and Kimberley D'Adamo investigate reflective practices that are integral to enhancing art students' creative capacities and sense of agency. They describe how an art class used individual and collaborative arts-based inquiries to foster high school students' metacognition—the ability to observe and reflect on one's own thinking and learning—and its implications for increased student autonomy, agency, and ability to persist through complex creative processes. Teri Evans-Palmer discusses how she structured and implemented artist journals as a tool to support reflection on personally held beliefs and development of creative self-efficacy among generalist preservice educators in “Teaching and Shaping Elementary Generalist Perceptions With Artist Journals.”

Creative agency is also cultivated through practices of cultural critique. Matthew Etherington shares his experience teaching a lesson on fashion in which middle school students learned how to critically analyze and creatively respond to ideologies embedded in everyday visual culture in “Criticizing Visual Culture Through Fashion Design and Role-Playing.” Jennifer Katz-Buonincontro examines art education inequalities in “Creativity for Whom? Art Education in the Age of Creative Agency, Decreased Resources, and Unequal Art Achievement Outcomes,” and she provides curriculum recommendations for developing creativity within the context of social justice art education.

Other art educators turn to contemporary art practice as way to encourage creative agency. In “Socially Engaged Art as Living Form: Activating Spaces and Creating New Ways of Being in a Middle School Setting,” Lynn Sanders-Bustle wonders whether socially engaged art, a contemporary art practice that invites audience participation and uses conversation as a medium, can be successful in schools. She offers a description of the process of setting up an art encounter in the school hallways and explores how creativity emerged relationally, in the novel ways students moved through the physical space and new kinds of social interactions between students and teachers.

Stephanie Harvey Danker looks at a series of contemporary artworks by socially engaged artist Charity White that addresses hostile architecture and built environments as experienced by people who are homeless or displaced by gentrification. In “Art Activism Through a Critical Approach to Place: Charity White's Prescriptive Space,” she outlines how one might go about designing a place-based art lesson that exploits the power of place in our lives and in the making of our identities. The Instructional Resources, “Power and Control: Responding to Social Injustice With Photographic Memes,” by Amanda K. Arlington offers teaching ideas centered around the photographic meme, a relatively new creative form and critical art practice with historical beginnings in protest photography of the civil rights era and the later influences from the work of conceptual artists such as Barbara Kruger and Lorna Simpson.

Thinking back on Carol's situation reminds us that the contexts of art and design education are varied and always changing. Though change can be scary and stressful at times, creative agency as a collective capacity means that each of us is not alone in navigating the unknowns. Creative potential exists everywhere in every context. To see creativity in this way might just open up new and empowering ways to face whatever may lie ahead.

Dear Art Education:

I recently had the pleasure of coming across the article Making Connections: Collaborative Arts Integration Planning for Powerful Lessons (Vol. 71, No. 4) by Tara Carpenter and Jayme Gandara. As the Director of Education and Programs for Young Audiences of Louisiana and a member of the leadership team at Young Audiences Charter School (YACS), I was thrilled to see that Tara had gained some inspiration during her visit to YACS during the 2015 National Art Education Association Conference. The focus of the article beautifully supports our arts-integrated school model, which relies on collaboration between classroom teachers and teaching artists to create and deliver arts-integrated curriculum featuring deep learning in both the arts and the connecting content area. At YACS, we believe deeply in the power of arts integration to ignite student learning and are encouraged to see that Tara and Jayme are disseminating this approach to teaching through their networks.

Collaboratively planning and implementing high quality arts integrated lessons can be more challenging than using traditional curriculum. Co-planning requires unpacking at least two sets of standards and analyzing them to ensure true connection. Co-teaching requires open communication, trust, and delineation of teaching roles. All of this takes time and energy, and we appreciate our faculty's perseverance. In recognition of this dedication, it is important to acknowledge their efforts, expertise, creativity, and authorship. The water mandala project that Tara observed during her visit to YACS, the project that spurred her and Jayme's creation of subsequent curriculum, was conceived by teaching artist Valorie Polmer in collaboration with her 3rd grade co-teachers, Monica Byrne, Monica Fontova, Chris Salerno, and Temetra Christian. I would very much appreciate if they could be credited for this work in future publications. Without them and their colleagues, our students would not have access to such high quality arts-integrated learning.

Kudos to Tara and Jayme for making arts integration accessible to teachers and students across the country. The doors at YACS are always open to other aspiring arts integrationists who would like to visit New Orleans to learn about our work.

Sincerely,

Jenny James

Young Audiences/Louisiana Wolf Trap

New Orleans, LA

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amelia M. Kraehe

Amelia M. Kraehe is Associate Professor of Art and Visual Culture Education at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Chicano was first used pejoratively to describe lower status brown-skinned Mexican Americans. During the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the term was imbued with pride as people of Mexican origin living in the United States began to self-identify as Chicano and Chicana. Today, Chicanx is preferred since it is gender neutral.

References

- Barnet-Sanchez, H. (2005). Tomás Ybarra-Frausto and Amalia Mesa-Bains: A critical discourse from within. Art Journal, 64(4), 91–93.

- Clapp, E. P. (2017). Participatory creativity: Introducing access and equity to the creative classroom. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cobb, W. J. (2007). To the break of dawn: A freestyle on the hip hop aesthetic. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Fendler, R., & Hamrock, J. (2018). Feeling free? Learning and unlearning in the enabling constraints of an art education summer program. Art Education, 71(4), 22–28.

- Glăveneau, V. P. (2014). Distributed creativity: Thinking outside the box of the creative individual. Cham/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer International.

- Graham, M. (2009). AP studio art as an enabling constraint for secondary art education. Studies in Art Education, 50(2), 201–204.