After 2 decades and one pandemic, this millennium has brought a range of technological, educational, and social developments. Just think—social media apps, online instruction, and global protests for racial justice are rapidly becoming the norm. Therefore, a question that begs to be answered is, How are art teachers adapting their skills for this new world? Moreover, are the teaching practices of yesteryear still relevant in this changing context? What do art teachers need to know and be able to do to be effective educators in the 21st century?

We come to these questions as art teacher educators, as mothers of young children, and as Black women. These identities provide an intersectional lens through which we have experienced much of the 21st century, including the pandemic of COVID-19 and the entrenched pandemic of systemic racism (i.e., White supremacism). With its overwhelming death toll across Native and Black communities and with people who appear to be of Asian descent targeted in the name of the “China virus,” COVID-19 may not be the source of injustices. However, it has amplified and aggravated preexisting systems that produce racial inequities and racist feelings in the United States and other White settler-colonial societies.

It is from this vantage point that we understand COVID-19 as a racial event. Images—streamed on handheld devices from news media and social media sources—have largely mediated our experience of the event. Often one of our children is nearby, enticed by the screen and curious to know, “Mama, what are you looking at?” How should we respond to racial events? Whose responsibility is it to address them?

Racial events can be traumatic and thus formative. All educators, no matter the context nor subject matter they are hired to teach, have a powerful role to play in shaping the formative years of human life. Parents, guardians, and the whole of society entrust them to do just that. Therefore, we believe all educators have an ethical obligation to address racial events head-on. However, we frequently see a strong reluctance to do so in art education. Art teacher education has scarcely addressed, let alone codified into professional standards or assessments, the capacities that enable an art educator to teach effectively and responsively in the context of racial inequality. These are capacities for antiracism that concerned parents and educators see as essential for all teachers (Kraehe & Herman, Citation2020).

In this article, we make the case that racial events demand our attention in art teacher education, and we show how we go about that in our own art teaching practice. Our rationale is twofold. First, there is substantial research that shows how subtle conveyances of disregard for the other (e.g., incidences with “Karens” and “Beckys”), as well as more blatant acts of physical violence (e.g., police officer pepper-spraying a 9-year-old Black girl or assaults on Asian and Asian American people as they go about everyday activities), impact people psychologically and physiologically to the point of increasing the instances and severity of disease and premature death (Sue, Citation2010). Second, race is not only a social construction; it is visually mediated (Acuff & Kraehe, Citation2020). The ability to perceive racial differences requires that one first learn the visual, symbolic, and aesthetic codes and conventions of racist ideology. If people have to be taught to see the world in racial terms, then they can also be taught to critique that way of seeing and develop countervisual practices of looking.

It makes good sense that the art classroom would provide opportunities for students to develop these skills, which we call visual racial literacy (Kraehe & Acuff, Citation2021). Visual literacy—without the race part—is already a part of a comprehensive approach to art education and is widely embraced by art educators working in schools and museums. Yet best practices for visual literacy are mute on the subject of race. We reject colormute practices, as they turn our attention away from systemic racism, thereby contributing to its maintenance (Pollock, Citation2004). Instead, we offer visual racial literacy as a foundational capacity for all art teachers that has remained underdeveloped in art teacher education.

Critical race scholar Lani Guinier (Citation2004) described racial literacy as an ability to perceive, decode, comprehend, and articulate racism in its various manifestations. Building on her ideas, we define visual racial literacy as critical, creative, and ethical skills needed to interpret and respond to the visual culture of racism. We have argued elsewhere that “where one lies on the spectrum from racially literate to racially illiterate depends upon whether the person has historical knowledge and cultural familiarity with racial iconography, dominant racial narratives, and the supremacist logics embedded within visual technologies” (Kraehe & Acuff, Citation2021, p. 43). It goes without saying that for students to develop visual racial literacy, they need educators who are visually and racially literate, adept in decoding and recoding iconographies, narratives, and technologies that reproduce and disseminate racist ideas. We model visual racial literacy in the next section by transforming a racial event into a teachable moment.

Activating Racial Literacy: Turning Racist Events Into Teachable Moments

Teachable moments. Real-time, on-the-spot learning is birthed from student-led curiosities, questions, actions, and even mistakes. Teachable moments are not planned. They are spontaneous and attend to the reality of time, location, and context. Many art teacher educators embolden future art educators to embrace these veers on the road by proclaiming, “Don’t be afraid to deviate from your lesson plan!” They encourage these future educators to notice and seize on moments of possibility. But are these future art educators given that same encouragement to deviate from the lesson when racism is at the center of the moment?

Daily, there are events that occur in our world that our students see, experience, consume and can feel in their bodies as they watch them on television and through social media platforms. These opportunities for educating are even more important as it relates to race and racism because they function as a kind of public pedagogy. Watching racism play out in real time through state sanctioned violence communicates that the structures that have been created to keep every one’s body safe regardless of color are faulty. Racist events, in society and in the classroom, left unquestioned teach students that racial hierarchy and access to power is non-negotiable.

When we activate visual racial literacy to unpack events, we find that common tactics, familiar and recurring, make oppressive racial structures resistant to change. These tactics are normalized and embedded in the cultural milieu of society. They are largely invisible because they fall into the scope of what the public is used to and what it understands to be “true.” Because of this, identifying certain events as racial can be hard to do. This is why racial literacy is critical. Below we “conjugate the grammar of race” (Guinier, Citation2009, para. 14). We have identified the 2021 U.S. Capitol Insurrection as a teachable moment and illustrate the ways racial literacy can be activated to unpack the visual lessons it taught the world about how racial oppression is sustained.

Unpacking “The Insurrection”

On January 6, 2021, White supremacists and White nationalist militia members invaded the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, DC, in an effort to disrupt the confirmation of the 2020 presidential election results. Close to 1,000 of these domestic terrorists, who were supporters of then President Donald Trump, illegally forced themselves into the Capitol building with weapons like bats, knives, bear pepper spray, and zip ties for securing human captives. The event resulted in six deaths, two of which were police officers. Two more officers died by suicide nearly a week following the event.

We have organized our analysis of the U.S. Capitol Insurrection through sensitizing concepts that “offer ways of seeing, organizing, and understanding experience” (Charmaz, Citation2003, p. 259). Sensitizing concepts are points of departure to interpret, investigate, and ask questions about what is happening in a particular context. While there are multiple sensitizing concepts that can be gleaned from the U.S. Capitol Insurrection, we primarily focus on Trump’s use of master narratives as a tool for reproducing White racial, social, and economic power.

Master narratives are “culturally shared stories that guide thoughts, beliefs, values, and behaviors” (McLean & Syed, Citation2015, p. 323). They can originate from and be sustained through language, imagery, actions, and constructed environments. Syed et al. (Citation2020) said that “while all master narratives are grounded in ethics, not all master narratives are moral” (p. 500). Thus, master narratives can play a significant role in justifying the maintenance of oppressive systems, including racism (Acuff et al., Citation2012). Beginning well before his presidential run in 2016, former President Donald Trump employed a master narrative that buttressed the racial event we now know as the U.S. Capitol Insurrection. “Make America Great Again,”Footnote1 his campaign slogan during both presidential bids, plays into an existential narrative that the current status of American life is a deterioration from the past state of American life. “Make America Great Again” likens sentiments about “the good ol’ days” when White men held enormous racial, social, and economic power.

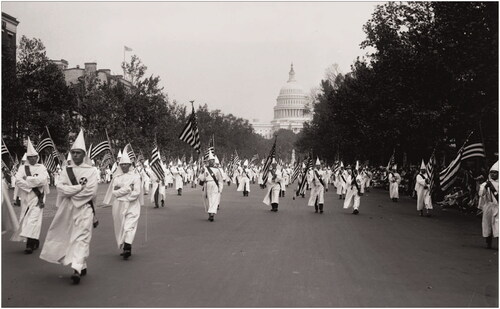

In a tweet, scholar Ruha Benjamin reminds us that “racial literacy is developing an historical & sociological toolkit to understand how we got here and how it could’ve been/CAN BE otherwise” (). As we consider the historical foundation on which Trump’s master narrative builds, we can identify the trends in America’s cultural practice of visualizing race. Consider D. W. Griffith’s record-breaking 1915 film Birth of a Nation (Griffith, Citation1915). The 3-hour film portrayed American life after the Civil War and Reconstruction as a dangerous and deep upheaval. This was done primarily through Griffith’s depiction of newly freed Black people as manipulative, menacing thieves whose freedom jeopardized the welfare of America. White men donned blackface to portray Black men as corrupt illiterates who raped innocent and pure White women. Ultimately, the film sparked the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, emerging more powerful than before in an effort to essentially “Make America Great Again” ().

Figure 1. Acuff screenshot of a series of three tweets shared by Ruha Benjamin on April 11, 2016. https://twitter.com/ruha9/status/719535690615242753?lang=en.

Figure 2. National Photo Company Collection, Ku Klux Klan parade, 9/13/1926. Washington, DC, on Pennsylvania Ave. NW. Public Domain. http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/npcc.16225.

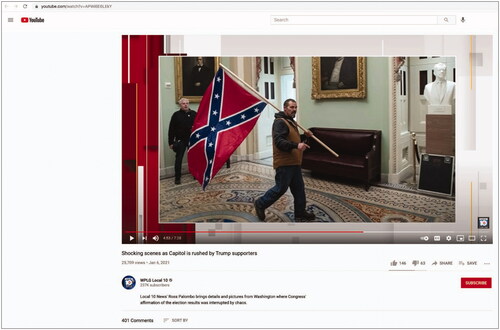

Akin to Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, Trump’s proclamation to “Make America Great Again” is a directive that encourages “Americans” (read White people) to work to regain a state of being that was lost, or better yet, stolen. Trump’s messages were racial dog whistles,Footnote2 setting the stage for a series of racist events to occur throughout his presidency and beyond. Worldwide, people watched these events, like the U.S. Capitol Insurrection, unfold live on television and computer screens and through social media platforms. Visual racial literacy helps to discern what we are witnessing through our senses. It is the capacity to identify and respond to the visual culture of racism. For example, the news media highlighted photos of a White insurrectionist walking the hallways of the Capitol with a Confederate flag (). In viewing the image, it is possible to decode the racial iconography present and the way it operates to create and sustain racism. The Confederate flag is a prominent symbol of support for American slavery, racial segregation, and Jim Crow era. “Since its debut during the Civil War, the Confederate battle flag has been flown regularly by white insurrectionists and reactionaries fighting against the rising tides of newly won Black political power” (Brasher, Citation2021, para. 2). How did such a historical symbol of racial oppression come to be taken up by those in support of making America great again? In what ways does the presence of the Confederate flag illustrate that “Make America Great Again” is synonymous with White dominance? With this example, one can see how the master narrative transitioned from being embedded in a written slogan, with words and text, to being embedded in a visual image.

Figure 3. Acuff screenshot of a local news segment in which the reporters shared an image of a Trump supporter holding a Confederate flag outside the Senate Chamber during the Insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, January 6, 2021. https://ktla.com/news/nationworld/man-photographed-with-confederate-flag-in-u-s-capitol-during-riot-is-arrested.

The master narrative nestled within “Make America Great Again” supported Trump’s false claims of election fraud. From election day up to the U.S. Capitol Insurrection, Trump denounced the heavily Democratic metropolitan cities populated with mostly BIPOC people, calling them hotbeds of fraud (Summers, Citation2020). Cities such as Philadelphia, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Atlanta were all named in his postelection lawsuits, which aimed to invalidate the votes in these cities. These unjustified claims were accepted by and large by his supporters because they played into the idea that America was being “stolen” by non-White and non-U.S. citizens. Trump’s use of dominant racial narratives pulled at the heartstrings of the “saviors of American democracy,” White supremacists and White nationalist militia members who needed to take the country back from non-White thieves. They considered themselves patriots fighting for the return to the status quo; when White power dominated, Black lives did not matter, and the economic and social needs of non-White people were suppressed. This master narrative is why we saw images of White domestic terrorists scaling the brick wall that surrounds the Washington, DC, Capitol building in an attempt to “stop the steal” ().

Educators across the country are sharing how the U.S. Capitol Insurrection made its way into their classrooms immediately following the event through informal discussions as well as formal curriculum (Brown, Citation2021). Many teachers focused on textual artifacts, like words, slogans, speeches, and news reporting. Yet many young people extract information about racial events through digital images on a screen. They need to be supported in developing the savvy needed to make sense of what they are seeing. Art educators, if equipped with visual racial literacy, can play a vital pedagogical role in that, helping students to recognize racial events when they occur, process their feelings, and think critically, creatively, and ethically about how they might respond (see Facing History and Ourselves, Citation2021; ShareMyLesson, Citation2021).

“Go for Broke”

In his 1963 essay, “A Talk to Teachers,” James Baldwin (Citation1985) wrote,

Let’s begin by saying that we are living through a very dangerous time. Everyone in this room is in one way or another aware of that. We are in a revolutionary situation, no matter how unpopular that word has become in this country. The society in which we live is desperately menaced… from within. To any citizen of this country who figures himself as responsible—and particularly those of you who deal with the minds and hearts of young people—must be prepared to “go for broke.” (p. 325)

The truth is that talking about race and racism is “difficult” only for people who rarely have to think about themselves as racialized beings and whose quality of life is not dependent on them having to use visual racial literacy on a daily basis. For the most part, discussions about race and racism are normalized within communities of color, particularly Black communities, as their lives depend on their racial awareness.

On the other hand, the general absence of these discussions in White communities is what makes them “difficult” when they suddenly arise. And this is why, we argue, to continue describing discussions about race and racism as “difficult” further centers Whiteness, aids and abets White fragility, and supports willful ignorance. The uncritical designation of race as a “difficult” topic creates and sustains angst around antiracist teaching altogether. To “go for broke” as Baldwin directs, educators—both White and non-White—need to be prepared to decenter Whiteness by normalizing classroom discussions about race and racism with confidence, care, and intention, and by activating visual racial literacy in ways that impact students’ relationships with race.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joni B. Acuff

Joni B. Acuff, Associate Professor of Arts Administration, Education, and Policy, College of Arts and Sciences, The Ohio State University in Columbus. Email: [email protected]

Amelia M. Kraehe

Amelia M. Kraehe, Associate Vice President for Equity in the Arts, College of Fine Arts, The University of Arizona in Tucson. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Trump was not the first president to use a version of this slogan. Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush used “Let’s Make America Great Again” in their 1980 campaign and at the Republican National Convention that same year.

2 Haney López (Citation2014) explained that dog whistling “constantly emphasizes racial divisions, heatedly denies that it does any such thing, and then presents itself as a target of self-serving charges of racism” (p. 5).

References

- Acuff, J. B., Hirak, B., & Nangah, M. (2012). Dismantling a master narrative: Using culturally responsive pedagogy to teach the history of art education. Art Education, 65(5), 6–10.

- Acuff, J. B. & Kraehe, A. M. (2020). Visuality of race in popular culture: Teaching racial histories and iconography in media. Dialogue, 7(3). http://journaldialogue.org/issues/v7-issue-3/visuality-of-race-in-popular-culture-teaching-racial-histories-and-iconography-in-media

- Baldwin, J. (1985). The price of the ticket: Collected nonfiction 1948–1985. St. Martin’s Press.

- Brasher, J. (2021, January 14). Op-ed: Why it wasn’t surprising to see Capitol rioters waving the Confederate flag. Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-opinion-confederate-flag-white-supremacy-capitol-20210114-qe5gctajrneuhijjlze6n7fxr4-story.html

- Brown, J. (2021, January 18). Rule of law and big feelings: How local teachers talked about the insurrection with students. The Register-Guard. https://www.registerguard.com/story/news/2021/01/18/how-teachers-kindergarten-high-school-taught-insurrection/4152743001

- Charmaz, K. (2003). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies for qualitative inquiry (2nd ed., pp. 249–291). Sage.

- Facing History and Ourselves. (2021, January 6). Responding to the insurrection at the US capitol. https://www.facinghistory.org/educator-resources/current-events/responding-insurrection-us-capitol?utm_campaign=fy21-educator-newsletter&utm_medium=email&_hsmi=105603581&_hsenc=p2ANqtz–HxK3n80g8GTk2Scjkr5kRFpadQPo05AUA722cNp4GkRBmuFiL2ikEaYgXc3bKuj_jXE733QwV9zdRMqTMIcRLvAkV0g&utm_content=105603581&utm_source=hs_email&fbclid=IwAR1_ZtdZHrId3oKw58UJgZuvGIFARyKbfU3ynkwnzj-CyQXBuffvUf_ublQ

- Griffith, D. W. (Director). (1915). Birth of a nation [Film]. Triangle Film Corporation.

- Guinier, L. (2004). From racial liberalism to racial literacy: Brown v. Board of Education and the interest-divergence dilemma. Journal of American History, 91(1), 92–118.

- Guinier, L. (2009, July 30). Race and reality in a front-porch encounter. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/RaceReality-in-a/47509

- Haney López, I. (2014). Dog whistle politics: How coded racial appeals have reinvented racism and wrecked the middle class. Oxford University Press.

- Kraehe, A. M., & Acuff, J. B. (2021). Race and art education. Davis.

- Kraehe, A. M., & Herman, D., Jr. (2020). Racial encounters, ruptures, and reckonings: Art curriculum futurity in the wake of Black Lives Matter [Editorial]. Art Education, 73(5), 4–7.

- McLean, K. C., & Syed, M. (2015). Personal, master, and alternative narratives: An integrative framework for understanding identity development in context. Human Development, 58(6), 318–349.

- Menakem, R. (2017). My grandmother’s hands: Racialized trauma and the pathway to mending our hearts and bodies. Central Recovery Press.

- Ong, A. D., Burrow, A. L., Fuller-Rowell, T. E., Ja, N. M., & Sue, D. W. (2013). Racial microaggressions and daily well-being among Asian Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(2), 188–199.

- Pollock, M. (2004). Colormute: Race talk dilemmas in an American school. Princeton University Press.

- ShareMyLesson. (2021, January 7). Three ways to teach about the insurrection at the U.S. capitol [Lesson plans]. https://sharemylesson.com/todays-news-tomorrows-lesson/insurrection-us-capitol

- Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. John Wiley.

- Summers, J. (2020, November 24). Trump push to invalidate votes in heavily Black cities alarms Civil Rights groups. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/11/24/938187233/trump-push-to-invalidate-votes-in-heavily-black-cities-alarms-civil-rights-group

- Syed, M., Pasupathi, M., & McLean, K. C. (2020). Master narratives, ethics, and morality. In L. A. Jensen (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of moral development: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 500–515). Oxford University Press.