In embracing her educational responsibility as a public intellectual, bell hooks (Citation1994) eloquently depicted the classroom as the most profound space of possibility. Her notion of engaged pedagogy is a simple yet complex “assumption that we learn best when there is an interactive relationship between student and teacher” (hooks, Citation2010, p. 19). hooks (Citation1994) encouraged us to liberate our classrooms using the principle that students are active participants in learning rather than passive consumers of knowledge. Rooted in Paulo Freire’s emphasis on praxis, hooks (Citation1994) challenged educators to act and reflect, for only then will we become change agents. For hooks (Citation2010), the interdependent nature of theory and practice is the vital link between critical thinking and practical wisdom because “when we create a world where there is union between theory and practice we can freely engage with ideas” (p. 186). From a close read of the articles for this issue, it is evident that the key tenet in each piece focuses on action and reflection for our youngest learners. I could not think of a better way to bring bell hooks into our conversation other than framing these articles within her teaching trilogy: Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (1994), Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope (2003), and Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom (2010).

In embracing her educational responsibility as a public intellectual, bell hooks (Citation1994) eloquently depicted the classroom as the most profound space of possibility. Her notion of engaged pedagogy is a simple yet complex “assumption that we learn best when there is an interactive relationship between student and teacher” (hooks, Citation2010, p. 19). hooks (Citation1994) encouraged us to liberate our classrooms using the principle that students are active participants in learning rather than passive consumers of knowledge. Rooted in Paulo Freire’s emphasis on praxis, hooks (Citation1994) challenged educators to act and reflect, for only then will we become change agents. For hooks (Citation2010), the interdependent nature of theory and practice is the vital link between critical thinking and practical wisdom because “when we create a world where there is union between theory and practice we can freely engage with ideas” (p. 186). From a close read of the articles for this issue, it is evident that the key tenet in each piece focuses on action and reflection for our youngest learners. I could not think of a better way to bring bell hooks into our conversation other than framing these articles within her teaching trilogy: Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (1994), Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope (2003), and Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom (2010).

Kristin Vanderlip Taylor asks a poignant question about how we can work together to create something. With a sharp focus on collaboration in creative tasks, she challenges us to take risks and to learn from and trust others, while accepting multiple perspectives as children make meaning through their visual arts experiences. Critical thinking, problem solving, creativity, innovation, communication, collaboration, social–emotional development, material thinking, and technology use remain at the forefront in preparing students for the global challenges they face, and serve as tools for transformative learning and active social involvement. When framed within hooks’s (Citation2010) notion of thinking as an action, Taylor’s piece presents an opportunity for the art classroom to become a space for bringing theory, practice, and social purpose together, which is at the heart of hooks’s notion of praxis. hooks (Citation2010) reminds us that our youngest are “relentless interrogators” who encounter their worlds of wonder with an innate curiosity and desire for knowledge. In searching for answers to “know the who, what, when, where, and why of life… they learn almost instinctively how to think” (p. 8). Critical thinking adds to the ongoing experience of wonder in young children, enhancing their abilities to be awed, enthusiastic, and stimulated by ideas that can radically open their minds (hooks, Citation2010).

Jayme Ellis endorses a choice-based approach in her 2nd- and 5th-grade art classrooms. She focuses on a smooth transition for her 2nd graders into their own artmaking while finding their artistic voice. She also works to support her 5th graders in continuing to develop an increasing sense of autonomy. Reframing her postpandemic teaching practice using a choice-based method, Kelly Hanning argues for a flexible curriculum modeling whole-group resiliency through artmaking during uncertain times. Hanning emphasizes using “big ideas” as the basis of sustained engagement and authentic artistic practice in museum education toward the shared goal of teaching young children. Hanning offers a good foundation for ideas with elements in place to build a productive conversation with hooks’s notions of engaged pedagogy, fostering dialogue, and learning partnership. hooks (Citation1994) celebrates the fact that as educators, we generate excitement within our classroom community, which “is deeply affected by our interest in one another, in hearing one another’s voices, in recognizing one another’s presence” (p. 8). As educators, we are continually retooling and rethinking our teaching practices, which in turn equip us with constructive methods to enrich learning. hooks (Citation1994) insisted that while ideas and phrases used by educators are often repetitive with overlapping contexts, there is no blueprint for teaching and learning. Her beliefs about engaged pedagogy call for recognizing each classroom as a different space, and “that strategies must constantly be changed, invented, reconceptualized to address each new teaching experience” (p. 11)—both articles do exactly what hooks asks us to consider.

Jessica Sack, Rachel Thompson, and Odette Wang focus on communities of practice that can form around early childhood education in museums. The authors claim that in the museum context, a community-of-practice model provides educators with the opportunity to sharpen their teaching practice through collaboration—namely the sharing of ideas, reflections, and strategies among colleagues. As museum educators begin to see partner organizations as communities of practice, their overlapping features can converge. Creating an open learning community warrants an ongoing understanding that every individual can shape the classroom dynamic through their contributions, which then become resources for both the teacher and the learner. Moreover, one can begin to see the classroom as a communal place, which then “enhances the likelihood of collective effort in creating and sustaining a learning community” (hooks, Citation1994, p. 8). Ultimately, our collective effort becomes a catalyst to generate the excitement to teach and learn, linking theory and practice by reflecting and acting on personal experiences. Further, these relationships strengthen the need for dialogue about equity, diversity, and inclusion (hooks, Citation2010). Given the ongoing challenges with equity, diversity, and inclusion, creating a community of practice with “diverse thinkers to work toward a greater understanding of the dynamics of race, gender, and class is essential for those of us who want to move beyond one-dimensional ways of thinking, being, and living” (hooks, Citation2010, p. 37).

Sarah Mostow recollects her experience of leading a professional development workshop for elementary art educators. Rooted in the teaching methods of Lois Lord, Mostow advocates the idea that for children to make art about their experiences, they must be asked. Lois Lord encourages teachers to structure their lessons with simple and relevant questions, which increases the time children spend directly manipulating art materials, developing figuration, and maximizing artmaking as a personal experience. Arguably, when learners acquire knowledge through their own cognitive efforts, learning becomes useful and relevant. For hooks (Citation1994), igniting that inner passion in educators is achieved through engaged pedagogy. Mostow’s article demonstrates this by teasing out the significance of independent thinking with each student finding their distinctive voice though their artmaking, emphasizing the applicability of engaged pedagogy in the art classroom as a means of empowering students. With meaningful teaching strategies at the heart of our practice, we provide the much-needed space for learning to happen deeply and intimately (hooks, Citation1994).

In her contribution, Susan R. Whiteland argues that autism should be considered as a form of neurodiversity and should not be pathologized. Her claim stems from the use of a problem-based learning model implemented by her students to develop art lessons for children with special needs that encourage opportunities for social development, self-expression, and communication. She further asks us to recognize the value of differentiated instruction and the positive effects of providing a variety of arts-based experiences for individual agency and confidence building. In their commentary, Aaron Ansuini, Juan Carlos Castro, G. H. Greer, and Aileen Pugliese Castro ask educators to maintain the orientation toward accessibility we experienced during the pandemic and to hold on to the understanding that we construct access—and barriers to access—every day. Their call is for us to carry this knowledge into our teaching practices, whether virtual or in person, and to be mindful of our participation in perpetuating and challenging ableism. Contextualizing Whiteland’s article and the commentary by Ansuini et al. within the teachings of bell hooks, one can see teaching as a performative act that creates conditions for innovation and change when confronted with the unanticipated. These spontaneous shifts in turn become change agents in drawing out the unique element within our teaching and learning spaces where art pedagogy happens daily. For educators to embrace the performative aspect of teaching, they must engage their audiences. hooks (Citation1994) rightly emphasizes that “teachers are not performers in the traditional sense of the word in that our work is not meant to be a spectacle. Yet it is meant to serve as a catalyst that calls everyone to become more and more engaged, to become active participants in learning,” arguing that engaged pedagogy creates participatory spaces for knowledge (p. 11).

Two European art educators, Ana Sarvanovic and Biljana C. Fredriksen, document a shared exchange of children’s play with materials during the pandemic. They argue that a “prolonged engagement” (Bresler, Citation2006, p. 56) with material challenged the students’ “alertness of senses” (Fredriksen, Citation2016, p. 108), making it possible to learn about nuances in human–material relationships. Rebecca Shipe’s dynamic visual narrative brings to light the challenges and opportunities of face-to-face teaching and learning in K–12 public education during the heightened COVID-19 crisis. Looking back at their Creative Classrooms program during the pandemic, Sarah Krauss and Mark LaRiviere share how the shift in their pedagogical practice presented opportunities for higher order thinking, creativity, and reflective artmaking. These storied experiences of teaching and learning from the pandemic build community in and out of the classroom, framing action and reflection. hooks (Citation2010) viewed personal stories as one of the most powerful ways to educate and create a community of practice in the classroom. When both students and teachers can “learn about one another through the sharing of experience, a foundation for learning in community can emerge” (hooks, Citation2010, p. 56). These three stories of the authors’ lived experiences offer us pedagogical tools, thus opening the space for individual voices, enhancing ways of being and knowing.

Offering a personal reflection on potential barriers to antiracist practices in art classrooms and ruminations on what one might do about it, Amelia M. Kraehe calls for action and reflection. As we continue to strengthen our antiracist practices, Kraehe reminds us to acknowledge that joy, married to righteous rage, is what motivates and sustains racial and social justice. Nestled within hooks’s engaged pedagogy, Kraehe urges us to revisit our teaching process “in a manner that respects and cares for” all students, rather than “a rote, assembly line approach” (hooks, Citation1994, p. 13). Thus, students’ life experiences become the means to endorse the curriculum. Voice, which hooks (Citation1994, Citation2003, Citation2010) used frequently in her writing, opens the possibility to move educators from a safe space to a place of resistance and challenges how we teach and learn while creating equitable and just classrooms. hooks (Citation2003) argued that racism has a firm grip on our culture, and only continual antiracism activism will repel that hold. She asserts that “we need to hear from the individuals who know, because they have lived anti-racist lives” and can guide everyone on what we can do “to decolonize their minds, to maintain awareness, change behavior, and create beloved community” (p. 40). It is only when community awareness is achieved, and change is embraced, that we can accomplish what both Kraehe and hooks ask.

In closing, as you read the articles in this issue, consider the union between theory, practice, and social purpose. As creative individuals, we are well positioned to generate excitement within our classroom community, which “is deeply affected by our interest in one another, in hearing one another’s voices, in recognizing one another’s presence” (hooks, Citation1994, p. 8). As artists and art educators, we are attuned to the “role imagination plays in helping to create and sustain the engaged classroom” (hooks, Citation2010, p. 59). Ruminating on her school years, hooks (Citation1994) shared:

School was the place of ecstasy—pleasure and danger. To be changed by ideas was pure pleasure. But to learn ideas that ran counter to values and beliefs learned at home was to place oneself at risk, to enter the danger zone. Home was the place where I was forced to conform to someone else’s image of who and what I should be. School was the place where I could forget that self and, through ideas, reinvent myself. (p. 3)

I invite you “to open [y]our minds and hearts so that we can know beyond the boundaries of what is acceptable, so that we can think and rethink, so that we can create new visions” (hooks, Citation1994, p. 12). Consider the power of your prophetic imagination as you act and reflect on “what we cannot imagine we cannot bring into being” (hooks, Citation2003, p. 195).

Rest In Power, bell hooks.

Author Notes

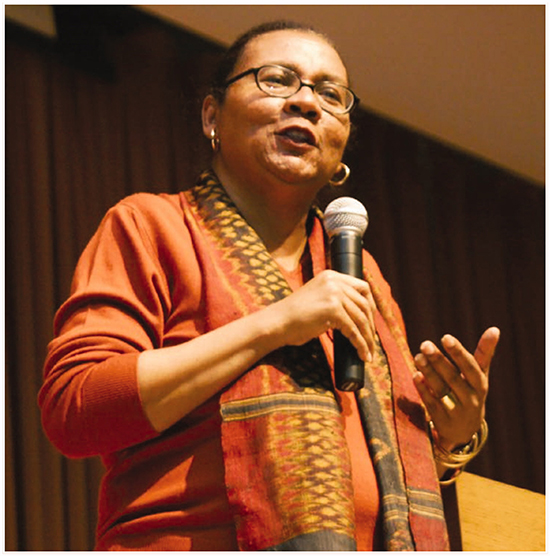

My heartfelt gratitude to Jolanda Dranchak and Lynn Ezell for powerfully bringing the ideas of bell hooks to the cover. It is my hope that the cover and editorial will reach the hearts of our readership in meaningful ways.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to the senior editor at this address: Art & Art Education Program, Box 78, Teachers College, Columbia University, 525 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027. Email: [email protected]

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ami Kantawala

Ami Kantawala, Adjunct Associate Professor of Art and Art Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Notes

A virtual memorial service for bell hooks, who passed away on December 15, 2021, at the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning in Lexington, Kentucky, was interrupted when a group of racist individuals Zoom bombed the event. During these polarizing times, people remain committed to disrupting events that celebrate our shared humanity, notes poet DaMaris Hill. For further reading see: https://www.kentucky.com/opinion/linda-blackford/article257740853.html.

References

- Bresler, L. (2006). Toward connectedness: Aesthetically based research. Studies in Art Education, 48(1), 52–69.

- Fredriksen, B. C. (2016). Attention on the edge: Ability to notice as a necessity of learning, teaching and survival. Visual Inquiry, 5(1), 105–114.

- hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

- hooks, b. (2003). Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope. Routledge.

- hooks, b. (2010). Teaching critical thinking: Practical wisdom. Routledge.

- hooks, b. (2013). Writing beyond race: Living theory and practice. Routledge.