Why

When lockdown in March 2020 was introduced, drama educators found themselves in a situation where they had to adapt their skills for entirely new challenges, because drama is a live and joint cocreation in a shared space. Process drama is a complex, unscripted, and improvisational subgenre, where both the facilitators and the students usually work in roles with ambiguous situations, and where multiple truths from different perspectives and real problems within the imaginary can be explored (Davis, Citation2014; O’Neill, Citation1995).

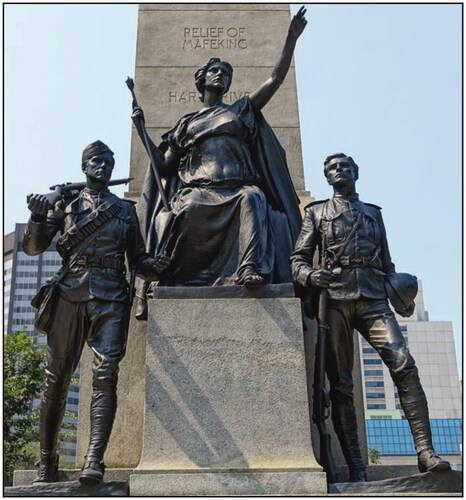

Kraehe (Citation2020) illustrated her recent editorial with the image of a masked statue. Kraehe (Citation2020) openly admitted her anxiety “about being asked to pivot to teaching online” (p. 5), but at the same time, she expressed her clear intention to “offer students a curriculum that would help them (and us) cope with the dislocation from school campus and disruption to routines and relationships” (p. 5). My process drama lessonFootnote1 was born from a similar anxiety with a similar intention. I wanted students (and myself) to reflect on our situation from a distance: What do we learn from the lockdown about humanness and society, about past, present, and future? “Very often history serves as a principal guide for present ways of thinking about what comes next,” wrote Kraehe (Citation2020, p. 7). Then she added, “But the future is wide open, perhaps wider now than ever previously imagined” (p. 7). How might considering these ideas serve as a foundation for examining issues and imagining improved futures or more just futures? The image of a masked statue is an ideal starting point of a process drama to trigger a discussion about these questions.

How

I conducted an online process dramaFootnote2 several times via Zoom. I framed the session as a joint exploration where, together with the participants, I was trying something out, and along the way, I would be learning as much (or even more) than they were. I made it clear that participation was voluntary, but that the process works better with active involvement. I invited the participants to explore a story that takes place in Solencia, a fictive small town in North Italy. I showed them an image of a Statue of Liberty () that stands on our main square and is an important symbol of the community. We jointly discussed what could be the three words on the pedestal that express our values and keep us together.

Figure 1. The imaginary Statue of Liberty in the main square of the fictive town of Solencia in Northern Italy. In reality, these are the central figures in the South African War Memorial in Toronto, Canada (Wikimedia Commons, Citation2015; image edited by the author). From Daderot, South African War Memorial—Toronto, Canada, 2015. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:South_African_War_Memorial_-_Toronto,_Canada_-_DSC00374.jpg). Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Then I asked the participants to create the story behind the statue. Each participant could add only one sentence, and the next speaker had to accept what had already been said and build the story further. One group jointly created a story where the central female figure was a freedom fighter who was loved by two male soldiers; one of them betrayed her, but the other saved her life and the revolution. Students also invented personal memories relating to this statue and shared them in the chat (e.g., “I was kissed for the first time ever under this statue”).

We entered the role of the City Council, which held its meeting on Zoom, and I took on the role of mayor. In this role, I told them that I had just spoken to the chief medical officer and that there were 52 new deaths in the previous 24 hours. We had a last matter to discuss: “Although it is strictly forbidden to go out without a good reason, someone did so during the night. Someone vandalized the statue on our main square.”

I stepped out of character, and I told them I knew that the words on the pedestal had been changed, the central figure got a mask, and also that there was some kind of a painting or image on the mask, which made most of the citizens extremely upset. But I did not know anything more than that. How had the words been modified? What was the image on the mask? While participants gave their responses, I used Zoom’s “annotations” to indicate how the statue had been modified. Following our previous example, the group suggested plenty of symbols that represented the abuse of power by men:

The values on the pedestal got amended in a cynical way.

The female figure’s mask was decorated with a penis, while one of the male soldier figures’ eyes was covered with a mask.

The other got his ears covered.

We then returned to our City Council roles and continued to improvise the meeting. I, as mayor, received a call that closed-circuit television had recorded the incident, and police had identified a 21-year-old student. We discussed what we should do with the perpetrator and decided to send a letter with our decision (e.g., one group decided to impose community work for her). One week later, in fictional time, we received a response. As mayor, I opened the envelope. Inside I found the same letter we had sent, with the following words scribbled on it in red: “Idiots. This is art.” I asked the council members what they thought. “Is this really art?”

In fictional time, we attended a press conference a few days later. Everyone took on the role of a journalist and had to decide which type of media they represented. Either the facilitator or a participant took on the role of the perpetrator, and the journalists were able to ask any kind of question. Further following our previous example, this group imagined the perpetrator as a young activist girl, who had an agenda to fight against the dominantly male governance of the city and how unjustly they handled the crisis.

Everyone wrote a headline in Zoom’s chat: Different media covered the story in different ways. Then, the participants wrote a typical Facebook comment that might be found under one of these headlines. Finally, we read the headlines and the comments together. I closed the session with the question, “If this were a poem written by a contemporary poet in locked-down New York, what would the title be?”

When

Just a few weeks after the (real-life) lockdown in 2020, spring was over, and this process had concluded; statues were modified all around the world as part of, or as a reaction to, the Black Lives Matter movement. Several notable art educators (recently Kraehe & Herman, Citation2020; and as a reaction to earlier incidents, Acuff et al., Citation2017; Bode et al., Citation2013; Link, Citation2019; and many more) urged art educators to reflect, rethink, and react.

Images of these modified statues put this drama session into an entirely new context. While a statue is a finished product and usually conserves a specific point of view of past events, the modifications are temporary and usually reflect an issue of the present. This interplay of permanency and temporality offers multiple layers of meaning for dramatic or artistic exploration. When you look at the image of a modified statue, what questions does it offer for you and your students to discuss in the intersections of art and vandalism, past and present, concrete and abstract, reality and fiction, or art and societal problems?

My students raised dozens of exciting questions during our sessions. If the artist defines her act as art, will it be art? Does one have the right to deny the virus in mass media openly? Where are the limits of free speech when humanity is facing a deadly pandemic? Which is stronger: our right to free mobility or our right to safety? I do not know the answer to any of these. Neither did my students. In process drama, we try to investigate such questions from as many perspectives as possible, accepting that we might not find an answer—or we might find multiple answers. As Kraehe (Citation2020) argued, “The future is wide open, perhaps wider now than ever previously imagined” (p. 7).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Adam Cziboly

Adam Cziboly, Associate Professor, Department of Arts Education, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences in Bergen. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Although this drama session was devised in Norway, its objectives can be interpreted within the framework of the National Core Arts Standards. This session belongs to Anchor Standard 11 (“Relate artistic ideas and works with societal, cultural, and historical context to deepen understanding”), serves the Enduring Understanding of the Visual Arts discipline in this Anchor Standard (“People develop ideas and understandings of society, culture, and history through their interactions with and analysis of art”), and contributes to all four levels of Performance Standards in 8th grade and upward (National Coalition for Core Arts Standards, Citation2014).

2 This drama session was conducted with groups of drama and teacher training students from Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Special thanks to Katrine Heggstad, who led some of the courses in which I was able to test this session, and to all students for being my coresearchers. A theoretical analysis of this session has been published in Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance (Cziboly & Bethlenfalvy, Citation2020).

References

- Acuff, J. B., Spillane, S., & Wolfgang, C. N. (2017). Breaking organizational silence: Speaking out for human rights in NAEA. Art Education, 70(4), 38–40.

- Bode, P., Fenner, D., & El Halwagy, B. (2013). The arts and juvenile justice education: Unlocking the light through youth arts and teacher development. In M. S. Hanley, G. W. Noblit, G. L. Sheppard, & T. Barone (Eds.), Culturally relevant arts education for social justice: A way out of no way (pp. 71–82). Routledge.

- Cziboly, A., & Bethlenfalvy, A. (2020). Response to COVID-19 Zooming in on online process drama. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 25(4), 645–651.

- Davis, D. (2014). Imagining the real: Towards a new theory of drama in education. IOE Press.

- Kraehe, A. M. (2020). Dreading, pivoting, and arting: The future of art curriculum in a post-pandemic world [Editorial]. Art Education, 73(4), 4–7.

- Kraehe, A. M., & Herman, D., Jr. (2020). Racial encounters, ruptures, and reckonings: Art curriculum futurity in the wake of Black Lives Matter [Editorial]. Art Education, 73(5), 4–7.

- Link, B. (2019). White lies: Unraveling Whiteness in the elementary art curriculum. Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education, 36(3), 11–28.

- National Coalition for Core Arts Standards. (2014). National Core Arts Standards: Visual arts. https://www.nationalartsstandards.org/sites/default/files/Visual%20Arts%20at%20a%20Glance%20-%20new%20copyright%20info.pdf

- O’Neill, C. (1995). Drama worlds: A framework for process drama. Heinemann.

- Wikimedia Commons. (2015, July 6). South African War Memorial—Toronto, Canada [Photograph]. Retrieved July 2, 2020, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:South_African_War_Memorial_-_Toronto,_Canada_-_DSC00374.jpg