The global COVID-19 pandemic continues to exert significant pressure on the higher education sector and the delivery of creative arts programs in Australia and abroad. With COVID-19 initiating a dramatic pivot to online learning, the pandemic has presented immediate challenges in student recruitment and retention, with predictably long-term impacts on engagement, progression, and broader student support. In Australia, the financial impact of the pandemic has led to the reduction or closure of creative arts offerings and a significant drop in investment in the creative sector, both of which will affect the production of cultural goods and services for years to come (Batorowicz & Johnson, Citation2020; Zhou, Citation2020). Indeed, Witze (Citation2020) asserted that “universities will never be the same,” while Cantrell et al. (Citation2020) suggested that “the pandemic not only represents a global health crisis but a global learning crisis too” (para. 1).

In the wake of this “overnight” shock to the education sector, it is essential to acknowledge that the sudden shift to online learning differs significantly from the gradual introduction of online education in the form of distance courses, hybrid programs, and blended offerings (Ploj-Virtič et al., Citation2021). The rapid transition to emergency remote learning has placed enormous stress on learning support systems, with the scale of change often surpassing the capacity of available resources and technologies (Hodges et al., Citation2020). As more university students now study remotely, online collaborative tools are more important than ever for optimizing the student experience and generating meaningful engagement (Frison & Tino, Citation2019, p. 228). As Lockee (Citation2021) explained, “Though rethinking of instructional approaches was forced and hurried, the [COVID-19] experience has served as a rare chance to reconsider strategies that best facilitate learning within the affordances and constraints of the online context” (p. 6).

In the present moment, art educators need to facilitate high-quality online learning experiences through the integration of collaborative learning, peer-based feedback, and effective educational technologies. In practice-based visual arts courses, it is also essential to focus on student engagement with the studio processes and material outcomes at the core of emerging arts practices. As such, online practice-based arts learning presents unique challenges for students attempting to learn processes to produce resolved outcomes. In the face-to-face setting, this type of learning can be supported by fostering a sense of community through the individual sharing of ideas and outcomes and regular peer and teacher feedback. In the online environment, this approach can be adapted and sustained through the implementation of online learning tools designed to support student-based sharing, while simultaneously promoting both artist development and artistic expression.

The Digital Affordances of Padlet

As the pandemic has established the imperative for innovative models of online engagement, the electronic bulletin board is a tool that continues to gain traction, as demonstrated through the widespread adoption and reported success of platforms like Padlet (DeWitt & Koh, Citation2020; Gill-Simmen, Citation2021; Kingston, Citation2018; Saetra, Citation2021). Padlet is an interactive online tool that allows contributors to exchange ideas and information synchronously and asynchronously. Padlet offers users free—albeit limited—usage, with extended functionality and additional storage available to individuals and institutions who upgrade to a paid plan. The tool’s visual interface and overall functionality resemble a virtual corkboard where students can upload or “pin” various forms of content, including images, videos, text, and web links. As both a digital app and a browser-based application, Padlet is compatible with iOS and Android. The tool can be accessed directly through a link or in a virtual learning environment (VLE). Users can collaborate on different types of “boards” (Wall, Canvas, Stream, Grid, Shelf), and each board’s layout, background, and color scheme are customizable. Padlet’s efficacy and flexibility are reflected in the literature, with Padlet described varyingly as “a virtual wall” (Kingston, Citation2018, p. 3944), “an interactive whiteboard” (Barna et al., Citation2020, p. 1), “a brainstorming map” (Dwinal, Citation2020, p. 17), and “a wall where students can hang their thoughts” (Frison & Tino, Citation2019, p. 228). As Padlet is established in scholarship, then, as a dynamic and widely accessible platform, the use of Padlet is further considered here in its capacity to contribute and innovate practice-based pedagogical approaches within a specific university-based visual arts curriculum in a time of the global pandemic.

As a collaborative tool that enables social interaction and engagement, Padlet promotes social learning through sharing practices that capitalize on users’ preexisting experiences with social media platforms, such as Instagram and Facebook. Padlet’s simple and intuitive interface allows students and teachers to post, link, or “like” content in a learning-centered community that exploits the pragmatic and affective functions underpinning the online behaviors of posting, sharing, and commenting. The easy transference of these behaviors to Padlet heightens the user’s acceptance of the platform while at the same time allowing more reticent users, or “lurkers,” to engage in receptive modes of communication until they are ready to “de-lurk” (Rafaeli et al., Citation2004, p. 4). Padlet’s “Attribution” function allows the board creator to enable anonymous posting so that students can ask questions, take risks, and experiment with different ideas, media, and techniques (Nadeem, Citation2019; Saetra, Citation2021). In this way, Padlet offers a “safe” space that allows students with differing levels of ability and forms of engagement to interact openly and asynchronously in a creative exchange that mimics the synchronous nature of in-person learning.

While a growing body of scholarship addresses the affordances and constraints of Padlet as an online learning tool, a systematic review of the literature reveals that Padlet’s application has yet to be widely explored in the creative arts. Most education research to date has focused on either Padlet’s impact on student engagement in the areas of business and science (Gill-Simmen, Citation2021; Nadeem, Citation2019) or collaborative learning in the fields of economics, education, and pharmacy (Frison & Tinto, 2019; Kingston, Citation2018; Saetra, Citation2021). This research centers on Padlet’s ability to promote knowledge creation and management (DeWitt & Koh, Citation2020), to support online mediation and scaffolding (Saetra, Citation2021), and to foster a sense of community, whether social or intellectual (Lomicka & Ducate, Citation2021). Many studies investigate Padlet’s value as both a tool for English language learning (Etfita & Wahyuni, Citation2020; Frison & Tino, Citation2019) and the development of writing skills more broadly (Kharis et al., Citation2020; Saepuloh & Salsabila, Citation2020). While these studies acknowledge that the overall success of Padlet depends on presage, context, and process variables, such as the amount and type of teacher intervention, individual level of technology comfort, and the student’s learning preferences, there are no studies to date that explore Padlet’s ability to support student engagement in the visual arts.

The Implementation of Padlet

In Semester 1, 2021, Padlet was piloted in the inaugural offering of a revised 1st-year studio course titled VIS1010: 2D Studio Foundations, offered at the University of Southern Queensland (UniSQ). In previous iterations of similar courses, teaching staff observed significant differences in the engagement levels of on-campus and online students. The online cohort was typically less engaged than their on-campus counterparts. For example, online students were encouraged to interact in the two historical studio-based courses in a text-based social forum embedded in Moodle, the University’s VLE. In the 2020 iteration of both courses, only five posts were shared to the social forums across a 15-week semester (VLE data, 2021). These low engagement rates gave rise to concern that the online learning experience was diminished by a lack of peer community, a limited sense of belonging, and the absence of a strong support network, all of which can engender feelings of isolation and disconnection (Farrell & Brunton, Citation2020).

In response to these limitations, Padlet was identified as a virtual collaboration tool that could support student sharing. Subsequently, a technological intervention was designed to encourage engagement, facilitating a sense of belonging, encouraging peer interaction, and mirroring the experience of studio-based exchange. To target these focus areas, a course-specific Padlet was embedded in Moodle, bridging the divide between online and on-campus cohorts, thereby expanding each student’s network through the formation of new social and intellectual relationships; the sharing of mutual creative pursuits; and the cross-pollination of ideas, techniques, and processes. The intervention was deemed particularly urgent, not only because of the surge in online learning during COVID-19 but also because the traditional studio is quintessentially a community of practice in which learning takes place in a social context through the reflexive exchange of ideas, iterative feedback, and peer review (Freedman et al., Citation2013; Workman & Vaughan, Citation2017). The forging of the studio-as-community helps students establish a network of peers who can become future colleagues and collaborators. Although this network can form organically in the on-campus setting, it is much more difficult to harness in the online space due to the flexible nature of distance learning, incompatible student schedules, and the physical isolation of working off-site (Gillett-Swan, Citation2017; Redmond et al., Citation2018).

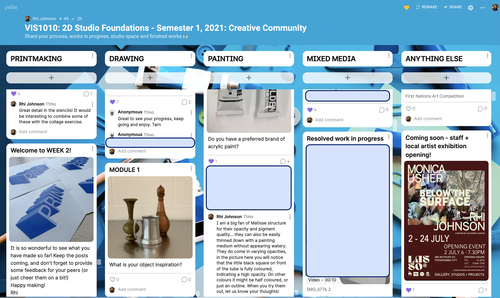

Thus, the course-specific Padlet for VIS1010 was introduced in Week 1 and promoted as both a collaborative space and a cohort-building tool. The Padlet, titled “Your Creative Community,” was constructed using the platform’s Shelf format, which allows content to be “stacked” in columns that are categorized by topic (). In the VIS1010 Padlet, five columns (or topics) were generated, with each corresponding to one of the five practical areas covered within the course: Printmaking, Drawing, Painting, Mixed Media, and Anything Else (). From the outset, students were encouraged to share images of their artwork in progress and use the “like” function as a preliminary endorsement indicator. The final column, Anything Else, was intended for the sharing of miscellaneous material: drawing resources, artist callouts, exhibition promotions, and anything the students deemed worthy of sharing. Notably, the Padlet was embedded in the course design so the teaching staff (themselves practicing artists) could prompt students to engage with the tool through modeling.

Figure 1. V1S1010 Padlet in Shelf view with five stacked columns: Printmaking, Drawing, Painting, Mixed Media, and Anything Else.

Initially, the course instructors (Johnson and McLean) modeled posting on the platform by sharing images of artwork exemplars from the first module and inviting students to share their unfinished work. Both teachers are professional artists with extensive teaching experience in traditional face-to-face learning and studio-based settings. The staff, however, needed more experience in delivering practice-based instruction in an online environment. As such, both instructors were tasked with pivoting to a hybrid mode of delivery in a stressful context (in this case, the pandemic). As the semester progressed, teaching staff sought to extend Padlet’s use from posting to commenting to close the feedback loop. Students were briefed on the importance of providing and receiving constructive feedback before the teaching staff modeled these behaviors to support this approach. This more nuanced feedback acknowledged student effort or interest, questioned ideas or theories, and provided recommendations for future applications. In this way, instructors could scaffold the students’ interactions by demonstrating how informal feedback can prompt self-criticism and improve unresolved work. Importantly, students were advised that the Padlet would not be formally assessed, thus alleviating performance pressure and reinforcing the use of Padlet as an informal learning space where students could seek guidance and advice both from their peers and the teaching staff. The teaching staff initially acted as facilitators who modeled feedback principles and behaviors to students who, in turn, adopted, imitated, and reappropriated those behaviors that were meaningful to them.

Results and Discussion

Its positive impact was clear from the early stages of Padlet’s implementation. Studio instructors deemed Padlet far superior to the previously used Moodle collaborative tools (group blogs, discussion forums, wikis, etc.). The social forums employed before the introduction of Padlet presented little opportunity for visual discussion or sharing. Consequently, in the two equivalent courses offered in 2020, forum interaction was limited to only five posts in each course. In 2021, however, the Padlet received 319 posts, 403 comments, and 1,164 reactions. As the number of students enrolled in the courses in 2020 (n = 39; n = 34) and 2021 (n = 48) was comparable, these figures represent an exponential growth in social engagement (from an average of 0.05 engagements per student in 2020 to an average of 39 engagements per student in 2021). Over the semester, students increasingly demonstrated a greater capacity and willingness to provide peer feedback, often initiating discussion, asking questions, and seeking advice, without prompting. For example, students often sought advice on technical matters, such as color mixing, and more conceptual issues, such as determining when a work is resolved. In turn, the teaching staff observed that students displayed heightened confidence when sharing their works in progress and providing feedback. The quantity and quality of posts increased as the semester progressed.

This transition from passive viewer to active participant was most evident at the semester’s end, culminating in a synchronous sharing and feedback session. In this session, the teaching team noticed that students were keen to engage in the peer-critique process; they were articulate in describing their ideas and processes and were generous in their feedback. Importantly, this observation was supported by self-report data collected through a student survey. The survey, conducted at the end of the semester, confirmed students’ appreciation of the platform. Of the respondents, 80% strongly agreed that Padlet enhanced their engagement with the course, while all respondents agreed that they preferred Padlet to the text-based forums. Moreover, 80% of respondents either strongly agreed or agreed that Padlet allowed them to connect with their peers and instructors in a way that fostered their sense of belonging, with one student highlighting the importance of the online tool for distance learning in particular: “As I am an on-campus student, I feel that the Padlet has been great, but I think if I were studying online, it would be a much more important element in my studies” (student feedback, 2021). Another student remarked that they appreciated the option to contribute to the Padlet anonymously, noting that “it was interesting to see others’ work” and “easy to download and access the Padlet app.” All respondents agreed that “Padlet was a supportive platform” for peer feedback. Given that this was the first time Padlet was implemented within a visual arts course at UniSQ, this positive response affirms Padlet’s ability to heighten student engagement and belonging.

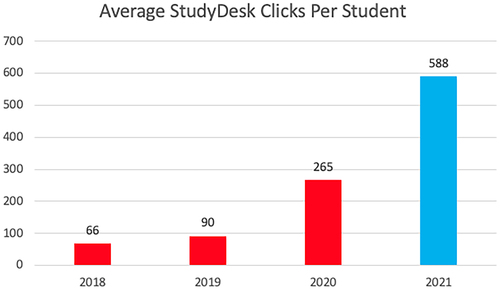

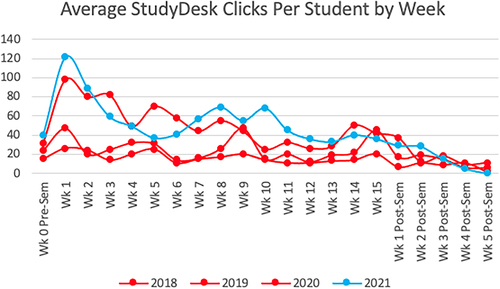

Moreover, Moodle analytics, which compare student engagement (as measured by clicks) across different course iterations, suggest that Padlet interaction had a flow-on effect across the semester. These analytics also reveal greater overall course engagement compared to previous years ( and ). In 2020, the course’s online learning platform had an average of 265 clicks per student per semester. In 2021, following the introduction of Padlet, the average number of clicks per student was 588—more than double the average number of clicks per student in the previous year (). Furthermore, while Moodle analytics demonstrate that course engagement steadily diminishes toward the end of the semester (regardless of whether Padlet is adopted), the 2021 iteration of VIS1010—in which Padlet was implemented—demonstrates a sustained level of engagement mid-semester that was not previously observed, which coincides with the feedback/feed-forward stage of the intervention (). Again, these data are an overwhelming demonstration of the platform’s positive impact on student engagement.

Figure 2. VSA1001 and VSA1002 for 2018–2020 (without Padlet) compared to VIS1010 2021 (with Padlet).

Figure 3. VSA1001 and VSA1002 for 2018–2020 (without Padlet) compared to VIS1010 2021 (with Padlet).

The final measure of Padlet’s success is its sustained uptake by teaching staff, who continue to find the application an efficient and effective learning tool and a mechanism for reducing instructor workload. Padlet has been embedded in other visual arts courses at UniSQ and, more broadly, across the School of Creative Arts. In addition, even in visual arts courses where Padlet has not been adopted, teaching staff have reported a flow-on effect in engagement. For example, in VIS1020: 3D Studio Foundations, the practice-based course that follows VIS1010, different studio instructors observed that the same cohort of students maintained a higher level of engagement than previous cohorts, readily engaging in sharing practices and processes and providing constructive feedback as early as Week 1. The fact that this cohort applied collaborative skills and knowledge to a new setting suggests that their social learning is transferable to different contexts. By extension, it is also possible that heightened levels of participation and engagement at the course level may be sustained at the program level.

Recommendations

Padlet is a collaborative tool that can be embedded in visual arts courses to enhance student engagement across different delivery modes. While the implementation of Padlet in VIS1010 was contextually instigated by the broader impacts of COVID-19, using Padlet within a post-COVID-19 context suggests that the platform’s application extends beyond stressful contexts. Certainly, Padlet is user-friendly and well-suited for creative arts students in its accessible visual- and text-based format. This way, embedding Padlet as a collective platform can build greater course cohesion in delivering an arts curriculum.

Padlet can be used as a course marketing tool that facilitates sharing of practice, ranging from initial concept planning to different forms of experimentation to showcasing resolved creative works. This recommendation is not designed to subsume physical practice’s integrity but to enhance overall engagement by promoting experimental processes and techniques in a shared context. This is partly achieved through Padlet being of similar format and function to other social media platforms. In this respect, Padlet can be used not only as a course marketing tool but as an online exhibition space that allows students to promote their artworks and, in doing so, develop their artistic agency and identity.

Padlet can be implemented as a site of interdisciplinary practice that cultivates artist development by building a supportive practitioner-focused network for online and on-campus students. Padlet’s use can be further expanded to other creative arts disciplines. Theatre, music, creative writing, and film and television students could all be included in the one Padlet to identify and monitor interdisciplinary synergies and points of difference. This would make for an even more dynamic outcome by using Padlet to instigate interdisciplinary learning networks that offer peer support and collaboration opportunities for creative arts students.

Padlet: Postpandemic

While the implementation of Padlet as an online collaborative tool was motivated by the COVID-19 pandemic, its tangible impact on student engagement will see the platform remain a permanent part of the visual arts program at UniSQ. Padlet allows students to build creative communities; it facilitates peer feedback and personal reflection; and it enhances resilience, skill development, and artist identity. The researchers affirm the potential of Padlet as an online engagement tool that can support creative practice and exchange.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rhiannan Johnson

Rhiannan Johnson, Senior Lecturer (Printmaking), Associate Head (Learning, Teaching, and Student Success), School of Creative Arts, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia. Email: [email protected]

Kate Cantrell

Kate Cantrell, Senior Lecturer (Writing, Editing, and Publishing), School of Creative Arts, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia. Email: [email protected]

Katrina Cutcliffe

Katrina Cutcliffe, Quality Partner, Learning and Teaching Futures, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia. Email: [email protected]

Beata Batorowicz

Beata Batorowicz, Associate Professor (Sculpture), Associate Head (Research), School of Creative Arts, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia. Email: [email protected]

Tanya McLean

Tanya McLean, Lecturer (Drawing and Painting), School of Creative Arts, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia. Email: [email protected]

References

- Barna, I., Hrytsak, L., & Henseruk, H. (2020). The use of information and communication technologies in training ecology students. E3S Web of Conferences, 166, Article 10027. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202016610027

- Batorowicz, B., & Johnson, R. (2020, October 23). The Lion and the Mouse: A tale of kindness and creative resiliency in a regional university. NiTRO: Non-Traditional Research Outcomes, 31. https://nitro.edu.au/articles/2020/10/23/the-lion-and-the-mouse-a-tale-of-kindness-and-creative-resiliency-in-a-regional-university

- Cantrell, K., Doolan, E., & Palmer, K. (2020, December 4). Doomscrolling, Zoom overload, and COVID fatigue: Teaching creative writing during the pandemic. NiTRO: Non-Traditional Research Outcomes, 32. https://nitro.edu.au/articles/2020/12/4/doomscrolling-zoom-overload-and-covid-fatigue-teaching-creative-writing-during-the-pandemic

- DeWitt, D., & Koh, E. H. Y. (2020). Promoting knowledge management processes through an interactive virtual wall in a postgraduate business finance course. Journal of Education for Business, 95(4), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2019.1635977

- Dwinal, C. (2020). Interactive visual ideas for musical classroom activities: Tips for music teachers. Oxford University Press.

- Etfita, F., & Wahyuni, S. (2020). Developing English learning materials for mechanical engineering students using Padlet. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 14(4), 166–181. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v14i04.12759

- Farrell, O., & Brunton, J. (2020). A balancing act: A window into online student engagement experiences. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17, Article 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00199-x

- Freedman, K., Heijnen, E., Kallio-Tavin, M., Kárpáti, A., & Papp, L. (2013). Visual culture learning communities: How and what students come to know in informal art groups. Studies in Art Education, 54(2), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2013.11518886

- Frison, D., & Tino, C. (2019). Fostering knowledge sharing via technology: A case study of collaborative learning using Padlet. In M. Fedeli & L. L. Bierema (Eds.), Connecting adult learning and knowledge management: Strategies for learning and change in higher education and organizations (pp. 227–235). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29872-2_13

- Gillett-Swan, J. (2017). The challenges of online learning: Supporting and engaging the isolated learner. Journal of Learning Design, 10(1), 20–30.

- Gill-Simmen, L. (2021). Using Padlet in instructional design to promote cognitive engagement: A case study of undergraduate marketing students. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, (20). https://doi.org/10.47408/jldhe.vi20.575

- Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020, March 27). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

- Kharis, M., Dameria, C. N., & Ebner, M. (2020). Perception and acceptance of Padlet as a microblogging platform for writing skills. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 14(3), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v14i13.14493

- Kingston, R. (2018). Technology enhanced collaborative learning in small group teaching sessions using Padlet application—A pilot study. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology, 11(9), 3943–3946. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-360X.2018.00724.2

- Lockee, B. B. (2021). Online education in the post-COVID era. Nature Electronics, 4, 5–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

- Lomicka, L., & Ducate, L. (2021). Using technology, reflection, and noticing to promote intercultural learning during short-term study abroad. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(1–2), 35–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1640746

- Nadeem, N. H. (2019). Students’ perceptions about the impact of using Padlet on class engagement: An exploration case study. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching, 9(4), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijcallt.2019100105.

- Ploj-Virtič, M., Dolenc, K., & Šorgo, A. (2021). Changes in online distance learning behaviour of university students during the Coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak, and development of the model of forced distance online learning preferences. European Journal of Educational Research, 10(1), 393–411. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.10.1.393

- Rafaeli, S., Ravid., G., & Soroka, V. (2004). De-lurking in virtual communities: A social communication network approach to measuring the effects of social and cultural capital. Proceedings of the 37th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2004.1265478

- Redmond, P., Heffernan, A., Abawi, L., Brown, A., & Henderson, R. (2018). An online engagement framework for higher education. Online Learning, 22(1), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1175

- Saepuloh, A., & Salsabila, V. A. (2020). The teaching of writing recount texts by utilizing Padlet. Indonesian EFL Journal, 6(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.25134/ieflj.v6i1.2637

- Saetra, H. S. (2021). Using Padlet to enable online collaborative mediation and scaffolding in a statistics course. Education Sciences, 11(5), Article 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050219

- Witze, A. (2020, June 1). Universities will never be the same after the coronavirus crisis. Nature, 582(7811), 162–164. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01518-y

- Workman, A., & Vaughan, F. (2017). Peer teaching and learning in art education. Art Education, 70(3), 22–28.

- Zhou, N. (2020, September 29). Australian universities to cut hundreds of courses as funding crisis deepens. The Guardian. http://amp.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/sep/30/australian-universities-to-cut-hundreds-of-courses-as-funding-crisis-deepens