ABSTRACT

Which traits are beautiful? And is their beauty perceptual? It is argued that moral virtues are partly beautiful to the extent that they tend to give rise to a certain emotion—ecstasy—and that compassion tends to be more beautiful than fair-mindedness because it tends to give rise to this emotion to a greater extent. It is then argued, on the basis that emotions are best thought of as a special, evaluative, kind of perception, that this argument suggests that moral virtues are partly beautiful to the extent that they tend to give rise to a certain kind of evaluative perceptual experience.

1. Introduction

After two centuries of neglect, the moral beauty theses, and particularly the form of the thesis which says that virtuous moral character is beautiful in itself, are enjoying a renaissance (see, for example, McGinn [Citation1999], Gaut [Citation2007], Paris [Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2020], and Doran [Citation2021]).

Despite this growing body of work suggesting that moral virtue is, in itself, beautiful, a number of important questions remain to be settled, principally the following. Which moral virtues, and indeed non-moral traits, are beautiful? And why are such traits beautiful when indeed they are?

Some of the existing answers that have been offered to date seem, prima facie, to be inconsistent with one another. With respect to the first question, some, such as Kant [Citation1764], have suggested that beauty is only found in ‘warm’ traits, whereas others, such as Gaut [Citation2007], have suggested that traits that seem colder, such as intelligence, are beautiful, too.

With respect to the latter question, Paris [Citation2018b, Citation2020] has defended the view that it is sufficient for beauty that something possesses good form and tends to be pleasingly apprehended as such, and that virtues generally satisfy this condition. By contrast, Kant [Citation1764] and McGinn [Citation1999] defend the stronger view that the tendency to give rise to a special kind of affect, which they variously term ‘sympathy’, ‘elevation’, and ‘ecstasy’, is necessary and sufficient for beauty; and Kant [Citation1764], at least, suggests that only a circumscribed range of virtues tends to give rise to this special kind of affect.

Setting aside these apparent inconsistencies, discussants in these debates, particularly Paris [Citation2018a, Citation2020] and myself [Citation2021], have tended to agree that, no matter what it is that makes at least some traits beautiful, their beauty is not perceptual, since traits do not have any perceptual properties.

In this article, I argue in favour of two principal claims. First, I defend the view that these tensions are only apparent, because the discussants of moral beauty are, in fact, expressing views that range over different kinds of beauty. Where Paris’s [Citation2018b, Citation2020] view targets a certain thick kind of beauty (expressed by beauty-form), the special-affect-based accounts are best thought of as targeting another thick kind of beauty (expressed by beauty-ecstasy).

With this in mind, I suggest that different virtues tend to possess different kinds of beauty, and that both of the existing kinds of accounts of the beauty of virtues are needed to explain this. To see this, I suggest that we need to recognize that the formalist account is content-neutral whereas a suitably formulated form of the special-affect-based account will be at least partly content-specific. I then present novel empirical evidence in favour of this idea.

Second, I suggest that the first argument has consequences for whether beauty is perception-dependent. I argue that Paris [Citation2018a] and I [Citation2021] might have been too quick to claim that the beauty of virtues is not perceptual. Beauty, in the thick sense of beauty-ecstasy, might in fact be perceptual, on the grounds that the special kind of affect that is appealed to by affect-based theorists is an emotion, and that emotions are best thought of as perceptual experiences of evaluative properties.

2. Existing Views of Which Traits Are Beautiful and Why This Is the Case

Supporters of the beauty of traits have differed with respect to how they quantify beauty across the domain.

For those whom we might call ‘particularists’ about the beauty of traits, only some virtues and non-moral traits are beautiful. Kant [Citation1764: 22–6], for example, suggests that only ‘warm’ traits such as being agreeable and tender-hearted are beautiful.Footnote1 Similarly, while Burke [Citation1757] explicitly claims that moral virtues are not beautiful [101–2], elsewhere he suggests that the traits of being weak and vulnerable [100], as well as people with ‘amiable’ and ‘domestic’ virtues [143–4], are beautiful (with the latter being beautiful in the context of their demise, at least).

By contrast, for those whom we might call ‘universalists’ about the beauty of traits, all virtuous traits, and indeed some non-moral traits, are beautiful. Gaut [Citation2007: 120], for example, claims that if a trait is virtuous then it is beautiful, and that colder non-moral traits such as ‘being intellectually gifted’ are beautiful, in addition to warmer traits such as having a sunny disposition.

With respect to the question of why traits are beautiful, when indeed they are, two proposals have been made. One answer, which tends to be associated with particularism about the beauty of traits, is that traits are beautiful when they are disposed to give rise to a special kind of affective state, which is variously called ‘sympathy’, ‘elevation’, and ‘ecstasy’, among other terms.

Kant [Citation1764: 22–3, 36, 44] suggests that traits are beautiful to the extent that they are loveable and lead to a ‘warm feeling of sympathy’ [22]. For him, as soon as such traits are brought in line with reason by, say, making ‘general affection towards mankind your principle’, which in turn leads you to act in a just fashion by withholding care from the individuals that pique your sympathies to be able to fulfil your duties to others, these traits become too ‘cold’ to be beautiful, and instead become sublime [ibid.: 23].Footnote2

Similarly, Burke [Citation1757] claims that the weak and vulnerable [100] and those with ‘amiable’ and ‘domestic’ virtues [143–4] tend to be beautiful, in virtue of their ability to give rise to what he calls ‘love’, which he characterizes in terms of melting feelings that tend to be expressed by closing one’s eyes a little and gently inclining them to the object of that state, opening one’s mouth slightly, and taking slow draws of breath and sighing [135–6].

McGinn [Citation1999: 110] offers a similar view, which can best be reconstructed as the claim that virtues are beautiful because they have the tendency to ‘afford aesthetic bliss’. He thinks that this special state of mind is necessary and sufficient for beauty generally. He characterizes this state in a more substantive manner, following Nabokov [Citation1959: 75], as the tendency to give rise to ‘a state of mind in which one is connected to other states of being in which art is the norm—where art involves curiosity, tenderness, kindness and ecstasy’, and that in these ‘other worldly states of being’ we are put ‘in contact with certain ideals’.

A similar suggestion, without McGinn’s weighty metaphysical commitments, has been made by psychologists such as Diessner et al. [Citation2008] and Haidt [Citation2000]. They suggest that moral goodness is only perceived to be beautiful when it gives rise to what they call ‘elevation’, where ‘elevation’ is a self-transcendent emotion that is paradigmatically characterized by, for example, feeling inspired, moved and touched, having a warm feeling in the chest, getting choked up, chills, feeling at one with the world, thinking that people are fundamentally good, and wanting to be morally better (for example, Landis et al. [Citation2009], Algoe and Haidt [Citation2009], and Doran [Citationforthcoming a, Citationforthcoming b]; this emotion has also been called ‘kama muta’ by, for example, Zickfeld et al. [Citation2018]).

Generally, the special-affect-based account, in the strongest form that makes this special kind of affect necessary and sufficient for beauty, as put forward by McGinn [Citation1999] and (arguably) others such as Kant [Citation1764], can be formulated in the following way:

Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy. A moral capacity, MC, is beautiful, if and only if MC has the disposition to give rise to the special state of mind that has variously been labelled ‘ecstasy’, ‘elevation’, and ‘sympathy’, etc. (hereafter: just ‘ecstasy’).

Moral-Beauty-Form. If a moral capacity, MC, is well-formed in the sense of having a constellation of parts that achieve MC’s proper end well, and tends to please as such, then MC is beautiful.

Turning to the ecstasy-based accounts that are not tied to particularism about moral beauty, such as McGinn’s [Citation1999], Haidt’s [Citation2000], and Diessner et al.’s [Citation2008] accounts, the picture is a little more complicated.

Since Haidt [Citation2000] and Diessner et al. [Citation2008] do not specify which features tend to cause ecstasy, and since they seem to be offering a psychological rather than a metaphysical account, these accounts might not be inconsistent with Moral-Beauty-Form. It might be the case, as a matter of empirical fact, that the kind of pleasant state to which the contemplation of people whose psychological faculties are well-integrated in the way specified by Moral-Beauty-Form tends to give rise is always ecstasy.

By contrast, since McGinn’s [Citation1999] account is explicitly formulated as a metaphysical account that offers necessary and sufficient conditions, as in Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy, and since it is at least conceivable that the contemplation of virtue in the way specified by Moral-Beauty-Form, as defended by Paris [Citation2018b, Citation2020], might give rise to a kind of pleasant state that is not identical to ecstasy, then, prima facie, Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy looks inconsistent with Moral-Beauty-Form. For suppose that someone contemplates the formal goodness of virtue with simple pleasure alone. Is it thereby beautiful? On Paris’s account, the answer would be ‘yes’, but, at least on McGinn’s account, the answer would be ‘no’.

3. Why Aren’t the Existing Views Inconsistent?

Despite these appearances of inconsistency (such as they are), I submit that both Moral-Beauty-Form and Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy are true, when the latter is formulated in the right way. I suggest that the source of the apparent inconsistencies, such as they are, derives from the fact that the accounts range over different kinds of beauty, as expressed by different concepts of beauty.

Which concepts of beauty do Moral-Beauty-Form and Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy intend to target? In contrast to one thin concept of beauty—beauty-aesthetic—according to which any aesthetically positive quality, such as being amusing or sublime, is beautiful, Paris [Citation2020: 519] explicitly claims that virtuous individuals are beautiful in a thicker sense of beauty—beauty-form—according to which something is beautiful if it is pleasant to the extent that it is well-formed.

Supporters of Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy, and indeed other ecstasy-based accounts, do not explicitly specify which concept of beauty they intend, but I suggest that they are best understood as intending another thick concept of beauty—beauty-ecstasy—which expresses the property that is possessed by many of the kinds of things that are listed in contrasts of the beautiful and the sublime, including, as noted by Burke [Citation1757: 102–7] and Kant [Citation1764: 14–18], the smooth, small, delicate, mild-coloured and things with gradual variation, such as grey-hounds, rolling hills, meadows strewn with flowers, and meandering rivers. As Passmore [Citation1951: 331] and Zangwill [Citation2001: 11] note, the paintings of, for example, Constable tend to have this kind of beauty, but those of Goya do not.

It is unlikely that things that possess this property have anything in common with one another apart from a tendency to give rise to the special kind of state of mind discussed in section 2. Burke [Citation1757: 135–45], Wordsworth [Citation1811–2: 349], and Passmore [Citation1951: 331], for example, note that such beauties invite loving, gentle, soothing, and melting responses—for instance, smooth things invite being caressed, delicate things invite gentle handling, and the appreciation of such kinds of objects tends to involve a melting feeling. Indeed, as we have seen, Burke [Citation1757: 135–6] claims that beauty just is that which tends to give rise to unitive feelings that tend to be expressed by closing one’s eyes a little and gently inclining them to the object of this state, opening one’s mouth slightly, and taking slow draws of breath and sighing.

Although this sense of beauty is not lexically marked in Indo-European languages such as English and German, it is lexically marked in languages from other linguistic families, such as the Japonic and Papuan family. The Iatmul of the East Sepik region of Papua New Guinea’s word for beauty—‘yigen’—is translated by Bateson [Citation1958: 141] as ‘beautiful, gentle and quiet’; and a family of Japanese lexical constructs seem to express aspects or determinates of this thick sense, including ‘mono no aware’ and ‘wabi-sabi’. Among such Japanese lexical items, ‘yūgen’ seems to come the closest to expressing the thickest sense of beauty, in referring to the beauty of human suffering, profound truths, and ‘gentle gracefulness’ (see, for example, Tsubaki [Citation1971: 55] and Ortolani [Citation1990: 125–6]).

If this is right, and if we think of the lexical item ‘beauty’ (and related items such as ‘beautiful’) as expressing a determinable concept—beauty—whose determinates include (though might not be limited to) beauty-aesthetic, beauty-form, and beauty-ecstasy, then Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy needs to be formulated as a sufficient account, in the following manner:

Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy*. If a moral capacity, MC, has the disposition to give rise to ecstasy, then MC is beautiful.

On Moral-Beauty-Form, considered by itself, moral traits should differ only with respect to their beauty just to the extent that they please to a different degree by having a greater harmony of parts in so far as, for example, some of their components, or constellations thereof, better achieve the relevant virtue’s proper function. There isn’t any reason to think that the kind of virtue that an individual possesses should make a difference to their beauty. Indeed, in explaining why his formalist proposal is more adequate than Parsons and Carlson’s [Citation2008] proposal, Paris [Citation2020] demonstrates his proposal’s commitment to content-neutrality. He suggests that, while much pornography is fit for its function of arousing audiences in the way that it, for example, highlights erogenous features, and is often pleasing to watch [ibid.: 520], the pleasure is primarily due to the arousing ‘depicted content’ rather than the way that the pornography achieves its end of arousing, and so is not beautiful to that extent [ibid.: 522]. With this in mind, it should be clear how Moral-Beauty-Form is well-placed to accommodate certain cases of the beauty of moral traits.

Compare the fully compassionate individual with the merely continently compassionate individual.Footnote4 The merely continently compassionate individual recognizes that they should be compassionate because it is the right thing to do, but they have not yet brought their affective tendencies into harmony with this belief. They rarely feel the kinds of tender feelings that would lead them to act in compassionate ways, and often desire to act instead in a self-interested fashion. Notwithstanding this, through strength of will, they regularly overcome their tendencies to act in self-serving ways, in order to alleviate the suffering of others. The fully compassionate individual, by contrast, recognizes that they should be compassionate because it is the right thing to do, and this is in harmony with their affective tendencies. They always feel tender towards the victims of harms, desire to act to alleviate the suffering of others because it is the right thing to do, and will themselves to act in this fashion.

Now, the fully compassionate person seems to be more beautiful than the merely continently compassionate individual, and Moral-Beauty-Form is well placed to accommodate this difference. While both the constellation of beliefs and the affective dispositions in the continently and the fully compassionate individuals achieve the end of compassion in leading to care for harmed individuals, they do not achieve it equally well. In line with Moral-Beauty-Form, the difference between the two constellations in how well they achieve the proper end of compassion is formal: the virtuous person’s rational and affective dispositions act in harmony with one another to orient the person towards others in the right kind of way. Indeed, in so far as the merely continently compassionate person fashions themselves into a more morally beautiful individual by bringing their reason and affective dispositions into harmony with each other, the merely continently compassionate person is behaving in an analogous manner to the artist who manipulates paint on a canvas to create harmonious forms. This explains why universalism is true of beauty-form, and thereby of beauty (by determinable inheritance): since any kind of virtue, and perhaps other psychologically complex capacities such as intelligence, can be more or less formally integrated and pleasing to that extent, any kind of virtue, and perhaps any kind of complex psychological capacity, can be beautiful.

However, given its commitment to content-neutrality, not all of the beauty of moral traits can be easily accommodated in terms of Moral-Beauty-Form.

Compare the fully compassionate individual to the fully just individual—someone who differs from the fully compassionate individual in terms of why they are virtuous, but not in how well they achieve their particular virtue. The fully just individual recognizes that they should be fair and should ensure that fairness prevails where possible because it is right, and this is in harmony with their affective tendencies. They always feel angry when they see someone being cheated or otherwise unfairly treated, and always desire to act in a way that brings restitution to the victims because it is the right thing to do, and always resolve to act in this fashion.

While such a just individual is certainly morally excellent, it doesn’t seem to be fully apt to describe them as ‘beautiful’ as such. Indeed, such an idea is borne out by ordinary usage of ‘beauty’ and ‘beautiful’ in English and German, as evident in various eighteenth-century claims about beauty, as we have already encountered. As we have seen, for particularists about beauty, such as Kant [Citation1764: 22–3, 36, 44, 59], not only are warm-hearted traits such as being kind, sympathetic, and agreeable more beautiful than traits such as fair-mindedness and courageousness, but these latter traits are not thought to be beautiful at all, and are instead claimed to be sublime.

If fully virtuous compassionate individuals are indeed at least more beautiful than fully virtuous just individuals, as these considerations suggest, then Moral-Beauty-Form doesn’t seem to have the ability to accommodate this difference. In each case, the constellation of psychological components achieves the proper functions of the respective virtues equally well, and so, to the extent that each is received with equal pleasure to that extent, they should be equally beautiful.

By contrast, Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy* is not, at least in principle, committed to content-neutrality, and so there is no obstacle to its being able to accommodate the fact that fully compassionate individuals seem to be more beautiful than fully just individuals. Indeed, there is at least some reason to think that Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy* should, in fact, be at least partly content-specific, and that it should suggest that fully compassionate individuals will in fact be more beautiful than fully just individuals.

The reason for this is that there tends to be a complementarity, or even a symmetry, between the components of the ecstasy response and many of the properties that tend to make for beauty in the sense of beauty-ecstasy. Indeed, in light of this complementarity, it is likely that, in appreciating beauty in the sense of beauty-ecstasy, we make ourselves into a mirror of the beautiful object, and we ‘feel into’ the beauty—as suggested by Lipps [Citation1903] with his notion of ‘einfühlung’.

To see this complementarity, consider the following. As we have already seen, and as Burke [Citation1757: 102–7] and Kant [Citation1764: 14–18] note, beauty in the sense of beauty-ecstasy is typically found in, for example, the smooth, small, delicate, mild-coloured, and things with gradual variation, such as grey-hounds, rolling hills, meadows strewn with flowers, and meandering rivers. And as Burke [Citation1757: 135–45] also notes, many of these beauties are beautiful because they invite tender, gentle, and melting responses—for example, smooth things invite being caressed, delicate things invite gentle handling, and the appreciation of such kinds of objects tends to involve the melting feelings common to the ecstasy response.

Moreover, looking specifically at the traits that tend to be found to be especially beautiful (if not exclusively so), as we have just seen, for Burke [Citation1757] and Kant [Citation1764], it is the gentle and soft traits, and those that invite or tend to lead to unity between people, such as cases of being vulnerable and compassionate, that are beautiful to the extent that they in turn elicit the gentle, soft, and unitive ecstasy response.

From this, it might be tempting to think that Kant [Citation1764] is right to think that the virtue of justice is not beautiful, and indeed that particularism about the beauty of traits is true, at least vis-à-vis beauty-ecstasy. This thought does not seem likely to be correct, however, as the complementarity between the properties of beauty in the sense of beauty-ecstasy and the ecstasy response extends to cases of moral beauty that might seem to most obviously be beautiful in the sense of beauty-form.

Some of the features of virtue generally (irrespective of the kind of virtue that they are) that seem likely to contribute to their beauty—such as being other-regarding and involving the overcoming of self-serving inclinations—also appear in the ecstasy response, which is partly characterized by feelings of transcending the self, and of wanting to orient oneself in a moral fashion towards others, and might therefore tend towards this response, too.

Moreover, just as virtues are partly beautiful to the extent that there is a harmony or unity between the constellation of psychological capacities that make up virtues, the ecstasy response tends to involve a sense of the world being harmonious and, indeed, of a sense of unity with the beautiful object and sometimes, through it, with everything, and so such harmony or unity might tend towards the ecstasy response, too.

With these clarifications, it should be clear that there is reason to think that universalism will be true of beauty-ecstasy, too: since instances of any kind of virtue are harmoniously integrated to some extent, and are likely to be other-regarding, instances of any kind of virtue are likely to possess some modicum of the disposition to lead to ecstasy, and so are likely to be beautiful in the sense of beauty-ecstasy to some extent. This remains true even if instances of specific virtues like compassion have a greater such disposition by having further—virtue-specific—features that also tend in the direction of giving rise to ecstasy.

Finally, for this same reason, and as ecstasy is often pleasant, it is also likely that the kind of pleasant state to which even beauty-form gives rise will tend to be ecstasy as a matter of fact; even if (as noted earlier), logically at least, it is possible that the mere pleasant apprehension of good form is sufficient for beauty, as per Moral-Beauty-Form.

4. Empirically Supporting These Views

Until now, I have argued that the apparent inconsistency between existing accounts of the beauty of traits could be resolved by recognizing that Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy (and perhaps other ecstasy-based accounts of moral beauty) is best thought of as targeting a specific thick concept of beauty—beauty-ecstasy—and that it should be formulated as a sufficient account—Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy*.

In arguing for this claim, and specifically in tracing how Moral-Beauty-Form and Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy* help to explain the beauty of different cases of moral beauty, a number of claims were made from the armchair, by appealing to certain intuitions, including, most importantly, the claims that fully compassionate individuals are more beautiful than fully just individuals, and that this is because the former tend to give rise to ecstasy to a greater extent. These claims would benefit from empirical support. Although these claims are metaphysical, and so not directly testable, it is surely right that if they are correct then we should expect that ‘the folk’ will respond in accordance with them, at least in so far as they are competent users of the concept beauty, and not labouring under some impairment, and that, to the extent that this is true (or false), the claims are supported (or unsupported, respectively). Indeed, empirical methods are all the more relevant in this particular context, given that many discussants of moral beauty agree that the responses of the folk are relevant in casting light on the nature of moral beauty, provided that the aforementioned conditions hold (see, for example, Paris [Citation2018a] and Doran [Citation2021]).

To see whether the folk would respond in line with the claims made in section 2, an empirical study was conducted.Footnote5

Materials and Methods: A sample size of 300 was decided upon (for the reasons that this sample size was targeted, see Supplementary Materials).Footnote6 312 participants from the online participant recruitment platform Prolific took part, and 12 participants were excluded as they failed the attention check, leaving a final sample of 300 (52% women, 47% men; mean age = 35, SD = 12).

Participants were randomly assigned to a control, fairness, or compassion condition, in which they were asked to vividly imagine the scenario described in the vignette presented to them (see Supplementary Materials, I, for the vignettes used). In each vignette, a person is described as being on their way to an important appointment to secure a loan on the day that a marathon happens to be taking place. In the compassion condition, the person is described as missing their appointment in order to provide care for the leading runner, who has fallen and injured themselves. In the justice condition, the person is described as missing their appointment to ensure that the leading runner, who has been cheated by another runner taking a shortcut, is recognized as the winner of the race. In the control condition, the person is described as seeing a runner in the marathon on their way to their appointment, and securing the loan needed.

The main features of interest, as discussed in section 2, were manipulated between these vignettes in a controlled manner. The people described in all of the vignettes overcame obstacles to arrive at positive outcomes, and all of the people described obeyed rules. Within this structure, there were a number of differences. The person in the control condition was described in the following ways: as not being as psychologically integrated as the people described in the two moral conditions (by, for example, not feeling inclined to follow the rules); as following prudential (rather than moral) rules; and as acting to overcome obstacles in order to benefit themselves rather than others. The people in the two moral vignettes were described as both being equally virtuous, and they differed only with respect to the kind of virtue that they displayed (that is, they were equally formally good). They were described in the following ways: as recognizing the happenings that are morally important (harm and injustice, respectively); as affectively responding in the right way to such happenings (they were described as hating seeing harm and injustice, respectively); as being motivated in the right way (they were described as desiring to care for harmed people and to ensure that people get treated fairly, respectively); as knowing what the right course of action is (that is, helping the harmed person and reporting the cheating so that fairness prevails, respectively); and as acting in line with this. These descriptions of the virtuous individuals are consistent with descriptions of compassionate and fair individuals in the literature on virtue ethics, including those upon which formalists such as Paris [Citation2020] have relied.Footnote7

Participants were asked to report how ‘virtuous (morally good)’ and ‘beautiful on the inside’ the individual described seemed to them. Participants were then asked how much ecstasy the individual described made them feel, using scales developed from existing measures of ‘elevation’, ‘kama muta’, and of the response to beauty in psychology (for example, Diessner et al. [Citation2008], Algoe and Haidt [Citation2009], and Zickfeld et al. [Citation2018, Citation2020]), as well as descriptions of the phenomenology of ecstatic experiences of beauty in philosophical works (for example, Plato [Citationc.370 BC], Bell [Citation1914], Laski [Citation1961], Beardsley [Citation1981], McGinn [Citation1999], and Doran [Citationforthcoming a, Citationforthcoming b]; see Supplementary Materials, I, for the items). Participants were also asked to rate how ‘caring and compassionate’ and how ‘fair-minded and just’ the individual described seemed, in order to see if participants categorize the virtues displayed in the vignettes in the same way as virtue ethicists do. Here are the results.

Main analyses. Since the normality assumptions of parametric tests were not met for the primary measures of interest (namely, virtue and internal beauty), Kruskall-Wallis one-way ANOVAs, and Dunn planned comparisons with Bonferroni corrections to account for multiple tests, were used to calculate the relevant inferential statistics.Footnote8

Judgments of being a ‘virtuous (morally good) person’ were affected by condition (H(2) = 103.23, p < .001, η2=.34). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the people described in the justice and compassion conditions were judged to be more virtuous than the person described in the control condition (justice versus control: p < .001, η2=.49; compassion versus control: p < .001, η2=.58), but, crucially, the person described in the justice condition was not judged to be more virtuous than the person described in the compassion condition (p = .51, η2=.08).

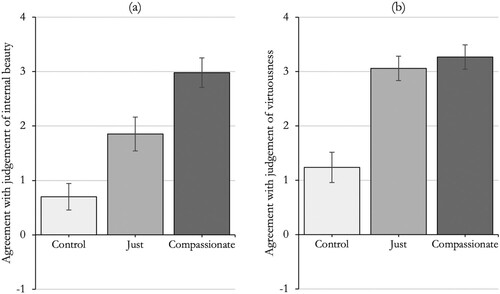

Judgments of being ‘beautiful on the inside’ were affected by condition (H(2) = 90.85, p < .001, η2=.30). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the people described in the justice and compassion conditions were judged to be more beautiful on the inside than the person described in the control condition (justice versus control: p < .001, η2=.29; compassion versus control: p < .001, η2=.59), and, crucially, the person described in the compassion condition was judged to be more beautiful on the inside than the person described in the justice condition (p < .001, η2=.29).

Judgments of being ‘fair-minded and just’ were affected by condition (H(2) = 95.85, p < .001, η2=.32). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the people described in the justice and compassion conditions were judged to be more just than the person described in the control condition (justice versus control: p < .001, η2=.55; compassion versus control: p < .001, η2=.48), but the person described in the justice condition was not judged to be more just than the person described in the compassion condition (p = .58, η2=.07).Footnote9

Judgments of being ‘caring and compassionate’ were affected by condition (H(2) = 138.21, p < .001, η2=.46). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the people described in the justice and compassion conditions were judged to be more compassionate than the person described in the control condition (justice versus control: p < .001, η2=.47; compassion versus control: p < .001, η2=.70), and the person described in the compassion condition was judged to be more compassionate than the person described in the justice condition (p < .001, η2=.23).

Figure 1. Graphs showing (a) mean agreement with the judgment that the person described in the vignette is ‘beautiful on the inside’, and (b) mean agreement with the judgment that the person described in the vignette is ‘a virtuous (morally good) person’, where error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals, and the scales run from ‘-4—Strongly disagree’ to ‘4—Strongly agree’.

Dimension Reduction Analysis. A principal component analysis using oblique rotation (direct oblimin) was conducted on all of the experience scales. Kaiser’s criterion of retaining components with eigenvalues that exceed 1 suggested a two-component solution. The item measuring the sense that the world is perfect or pure, and the item measuring a sense of profundity or meaningfulness loaded on both components, and so were excluded (with the threshold for loading set at .4: Stevens [Citation2002]), and so the PCA was re-run without these variables. Although the eigenvalue for the second component fell slightly below 1, two components were retained, as the two components were theoretically meaningful. One component clearly referred to pleasant transformational aspects of ecstasy—where we feel delighted, moved, inspired, and at one with the object of the state, and feel a desire to become morally better. A second component clearly referred to rarefied, and often hedonically ambivalent, bodily sensations, such as feeling chills, goosebumps, getting choked up and having moist eyes (for details of the loadings, the component correlation matrix, and various goodness-of-fit indicators, see Supplementary Materials, II).

Reliability analyses were run to assess the consistency of the items that loaded onto the transformational component and the rarefied bodily sensations component. The set of items that loaded onto the pleasant transformational component had a Cronbach’s alpha of .96, and the set of items that loaded onto the rarefied sensations component had a Cronbach’s alpha of .83, indicating that the scales have excellent and good consistency, respectively. Therefore, overall transformational ecstasy and rarefied sensations scales were composed by taking the mean of the relevant items.

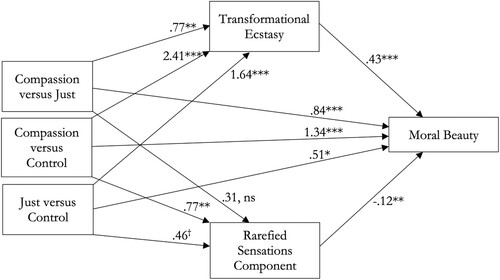

Mediation analyses. To test whether the different conditions affected judgments of moral beauty via the components measured, a parallel multiple mediation analysis was conducted, using ordinary least squares path analysis and robust standard error estimates (Hayes [Citation2017]: see ), with the transformational ecstasy component and rarefied sensations component as mediators.

Figure 2. A multiple mediation analysis showing the effect of condition on judgments of internal beauty via transformative ecstasy and rarefied sensations. ***= p < .001, **= p < .01, *= p < .05, and †= p < .1. Each coefficient in this figure is an estimate of a one-unit change in the variable concerned on another variable (in terms of the scales used to measure these variables), while keeping constant the other variables in the model. So, for example, being in the compassion condition was estimated to result in feeling .77 more units of transformative ecstasy, compared to being in the justice condition; and every one-unit increase in the transformative ecstasy felt was estimated to result in a .43 increase in the internal beauty scale.

Bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals for the effects of the conditions on judgments of internal beauty indirectly via experiences of transformational ecstasy and rarefied sensations in turn, indicated a number of significant indirect and direct effects. When holding constant the rarefied sensations component, the just individual was judged to be more beautiful than the individual in the control condition, as a result of giving rise to more transformational ecstasy (.70, 95% CI [.43, 1.00]); the compassionate individual was judged to be more beautiful than the control individual, as a result of giving rise to more transformational ecstasy (1.03, [.70, 1.39]); and the compassionate individual was judged to be more beautiful than the just individual, as a result of giving rise to more transformational ecstasy (.33, [.09, .60]). When holding constant the transformational ecstasy component, the compassionate individual was judged to be less beautiful than the control individual, as a result of giving rise to more rarefied sensations (-.10, [-.22, -.01]). Overall, both the just individual and the compassionate individual were found to be more beautiful than the control individual via the combined effect of both components (just versus control: .64, [.38, .93]; compassion versus control: .93, [.63, 1.26]), and the compassionate individual was found to be more beautiful than the just condition via the combined effect of both components (.29, [.09, 51]).

Independently of the effect of the conditions via transformational ecstasy and rarefied sensations, the just individual was found to be more beautiful than the control individual (b = .51, t(295) = 2.49, p < .05); the compassionate individual was found to be more beautiful than the control individual (b = .1.34, t(295) = 6.38, p < .001); and the compassionate individual was found to be more beautiful than the just individual (b = .84, t(295) = 4.60, p < .001).

Discussion. The results indicate that the folk respond in the way that would be expected if the claims made in section 2 are correct, and, in so far as this is the case, those claims garner strong support.

As expected, first, both kinds of virtuous individuals were more virtuous (and thereby more formally good) than the individual in the control condition. Moreover, both kinds of virtuous individuals were judged to be more beautiful on the inside, to the extent that they were received with ecstasy, and specifically with the transformative ecstasy component, which was indeed revealed by the principal components analysis to be the pleasant state to which virtue tends to give rise. As such, these data support Moral-Beauty-Form (as per Paris [Citation2018b, Citation2020]).

Second, also as expected, Moral-Beauty-Form cannot easily accommodate all of these findings; Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy* is needed, too. The compassionate and just individuals were not found to differ in terms of how virtuous they were judged to be, and so were not found to differ in the property expressed by beauty-form, but the compassionate individual was found to be more internally beautiful than the just individual to the extent that they gave rise to ecstasy, and specifically to the transformative component of it, presumably due to the virtue-specific features of compassion that tend towards ecstasy.Footnote10

In addition to these central findings, there were two other important findings. The just and the compassionate individual were judged to be more internally beautiful than the control individual, and the compassionate individual was judged to be more internally beautiful than the just individual, independently of their respective tendencies to give rise to the experiences measured. To the extent that this isn’t due to measurement error—for example, some of the components of the ecstasy construct might not have been measured—these findings may suggest that there are further reasons why virtuous people are beautiful, and perhaps even further concepts of beauty, in addition to those identified in section 2.

When holding transformative ecstasy constant, the compassion condition, and perhaps the justice condition, tended to give rise to greater rarefied sensations to a small extent; and, in the case of the compassion condition, this acted to slightly decrease judgments of internal beauty. One possibility is that the rarefied sensations component forms a principally colder aspect of the ecstasy response, and thereby serves to decrease attributions of moral beauty somewhat. Indeed, the chills, goosebumps, and tears responses have been found to admit of colder varieties (see, for example, Maruskin et al. [Citation2012], Cotter et al. [Citation2019], and Bannister [Citation2019]); and, as Kant [Citation1764: 23] suggests, feeling that something is ‘cold’ might tend to count against its being beautiful. These additional findings warrant further work in the future.

5. Is Moral Beauty Perception Dependent?

With the argument and evidence for Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy* now laid out, in this final section I wish to trace briefly one important consequence of Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy*.

Paris [Citation2018a] and I [Citation2021] briefly make the following argument.

(P1) At least some moral virtues are beautiful in themselves,

(P2) No virtue has perceivable properties in itself,

(C) Therefore, if a virtue is beautiful in itself, its beauty is not perceptual, and beauty is not perception-dependent.

I want to suggest, contra Paris [Citation2018b] and myself [Citation2021], that at least one of the species of beauty that attaches to moral virtues is perceptual in a special sense, and that, to this extent, some moral beauty should be accepted even by those who hold a perception-dependent conception of beauty.

The first step to seeing why this is the case comes from recognizing that emotions are most plausibly a special kind of perceptual experience, given that the emotions are analogous to more paradigmatic sensory kinds of perception in ways that allow them to perform the same kinds of role in our mental life.Footnote11

Our sensory perceptual capacities are domain-specific, give rise to representations with a distinctive phenomenology, and provide direct access to their proprietary aspect of the world in virtue of the fact that the internal operation of these capacities is largely impenetrable to our beliefs and insensitive to our wills, and because the representations that they produce are not the result of an inferential process. For this reason, the sensory representations produced by our sensory capacities provide prima facie justification for the corresponding beliefs.

Our visual systems, for example, are sensitive to visible objects and properties (but not, for example, olfactory objects and properties), and they produce representations with a distinctive visual phenomenology in a direct fashion. The sensory perceptual representation of the red object in front of me as red is caused directly by the red object and is not the result of any rational inference from, say, my knowledge of the object as having a specific reflectance profile, and the process producing this perceptual representation cannot be affected by my will or my beliefs about, for example, the lighting conditions. As such, the sensory perceptual representation of the object as red provides prima facie justification for the belief that there is a red object in front of me.

Similarly, our emotional systems seem to be sensitive to different kinds of evaluative properties—with our fear systems being sensitive to frightening things and properties (but not, for example, offensive things and properties)—and they produce representations with a distinctive affective phenomenology in a direct fashion. The evaluative perceptual representation of the big snarling dog approaching me as frightening during experiences of fear is directly caused by the dog and is not the result of any rational inference from, say, knowledge that the dog is a particular size, and the process producing this evaluative perceptual representation largely cannot be affected by my will or beliefs about, for example, whether the dog has been trained to merely display these appearances on command. As such, the evaluative perceptual representation of the dog as frightening provides prima facie justification for the belief that the dog is frightening.

As such, our emotions, like our sensory perceptual systems, seem to give us direct access to the world, and to aspects of its appearance in particular, and so are justly regarded as perceptual systems. If emotions are perceptions, as these considerations suggest, then why might not at least some of the beauty of virtues be perceptual?

As we saw in section 2, beauty in a certain thick sense has been thought to be simply the disposition to give rise to a certain emotion—namely, ecstasy—and, as we have seen in section 3, consistent with this view (and as per Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy*), there is evidence that the tendency to give rise to this emotion is sufficient for a virtue to be beautiful. As such, it is plausible that ecstasy perceives the beauty of virtues, in the sense of beauty-ecstasy.

Additional considerations also suggest that ecstasy perceives beauty in the sense of beauty-ecstasy. Such a view is similar to the idea, which was prominent in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British aesthetics and developed most notably by Hutcheson [Citation1725], that there is a seventh, internal, sense for detecting beauty—where this capacity’s status as a sense was thought to be granted by its immediacy of operation, independence of our will, innateness, and independence of our beliefs. Like this idea, the idea that ecstasy perceives beauty in a particular sense is able to accommodate a number of facts, which are related to the reasons outlined above for thinking that emotions are perceptions, and which suggest that beauty in the sense expressed by beauty-ecstasy (and perhaps more generally) is a perceptual property. These include that we seem to be struck by beauty in the sense of beauty-ecstasy and seem to find it in the world directly, rather than reasoning towards it,Footnote12 that there is something that it is like to find something beautiful in the sense of beauty-ecstasy, and that at least typically we need to be directly acquainted with objects in order to know whether they are beautiful in the sense of beauty-ecstasy (rather than being able to rely on the testimony of others).

Moreover, the view that ecstasy perceives beauty, in the sense of beauty-ecstasy, is also consistent with the fact that beauty in the sense of beauty-ecstasy is a higher-order property, which lies in a range of kinds of sensory, and indeed non-sensory, objects, when considered together with the fact that the emotions perceive higher-level properties. As we have seen, the sound of a bittersweet sonata, the sight of a meandering river, and the thought of compassion can be beautiful, in the sense of beauty-ecstasy. The emotions generally are disanalogous from sensory perceptions in so far as the emotions are higher-order perceptions that can take as inputs, for example, visual and auditory representations as well as non-sensory representations. The sight of an approaching snarling dog, the sound of a loud noise, and the thought of a global recession can induce fear and thereby be perceived as frightening. As such, since ecstasy is an emotion, the view that ecstasy perceives beauty, in the sense of beauty-ecstasy, can elegantly accommodate the fact that beauty in this sense seems to be a higher-order property.Footnote13

To the extent that the idea that ecstasy perceives beauty in a specific sense is also consistent with these additional facts, it thereby gleans support.

If the foregoing is right, then (P2) is false: to the extent that moral traits give rise to ecstasy, we tend to perceive the beauty in the sense of beauty-ecstasy they possess. As a result, it doesn’t follow, from the mere fact that at least some virtues are beautiful, that their beauty is not perceptual; and, moreover, even those who are hostile to the claim that traits can be beautiful in themselves, because it seems to violate the perception-dependence of beauty, should embrace it to some extent.Footnote14

6. Conclusion

I have suggested that competing accounts of which traits are beautiful, and of why they are beautiful (when indeed they are), are in fact consistent with one another because they range over senses of beauty that differ in their thickness—namely, beauty-form and beauty-ecstasy. To show this, I have argued that ecstasy-based accounts should be formulated in a sufficient manner—Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy*—and that this is needed in addition to Moral-Beauty-Form to explain the fact that compassion is more beautiful than being just. I have suggested that the truth of Moral-Beauty-Ecstasy* has an important consequence when considered in light of the fact that the emotions seem to be a kind of perception: it shows that the beauty of traits is in fact at least partly perceptual, and so the existence of moral beauty in this sense should be even more widely accepted than it currently is.Footnote15

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 More precisely, Kant [Citation1764] holds that qualities such as tender-heartedness, which are beautiful, are only ‘good moral qualities’ [22] or ‘adopted virtues’ [25], as they can prevent people from fulfilling their duties.

2 Among the other virtues that Kant considers sublime, rather than beautiful, are heroism and courage (e.g. [Citation1764: 22, 59]). In distinguishing between artificial and natural virtues, Hume may be thought to carve up the virtues in a similar manner. He seems to differ from Kant, however, in thinking that artificial virtues such as being just are also beautiful, and in thinking that, unlike in the case of natural virtues, identifying the beauty of the artificial virtues requires recognition of the fact that they tend towards the common good, together with sympathy for the beneficiaries of such virtues (see, e.g., Hume [Citation1739–40: 498–500, 577–80, 618]).

3 A similar formalist answer has been suggested with respect to the beauty of fair states of affairs. Scarry [Citation2006: 63, 65] suggests, for example, that, as justice as fairness is, as Rawls puts it, ‘a symmetry of everyone’s relations to each other’, it possesses the ‘attribute most steadily singled out over the centuries’ to make for beauty.

4 For a discussion of the fully virtuous versus the merely continent, see, e.g., Foot [Citation1978: 10].

5 Ethical approval for this study was granted by the University of Sheffield.

6 Supplementary materials are available at (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/24Q5F).

7 See, for example, Zagzebski [Citation1996: 99, 131, 134, 135–7] on the fair person and the compassionate person, and on the nature of virtues generally, and Adams [Citation2006: 14–35].

8 Parametric tests tend to be robust against violations of their assumptions with larger samples, such as the sample for this study; parametric tests give the same results as those reported here; and so, for ease of interpretation, means with 95% confidence intervals are presented in .

9 The lack of a significant difference in judgments of being ‘fair-minded and just’ between the justice and compassion condition is probably the result of the fact that it is more difficult to precisely measure justice in the sense of fairness. As noted by Miller [Citation2017] ‘justice’ is often taken to mean ‘what is generally right’, and ‘morally good in the sense of what we owe to one another’, and so this measure probably tracked compassion, too.

10 A reviewer suggests, on the basis of aspects of Hume’s aesthetics, that these findings might be inconclusive, as the appreciation of the beauty of justice might require expertise in the form of, e.g., recognizing that justice tends towards the common good, and empathizing with the beneficiaries of the just act, as well as meeting Hume’s general requirements for arriving at accurate judgments of taste (see, e.g., Hume [Citation1739–40: 498–500, 577–80], [Citation1757], and [Citation1777: 172–3]). This doesn’t strike me as convincing. Hume suggests that the recognition of the nature of justice and the extension of empathy are also required for thinking that artificial virtues are morally good. If this is required, then arguably this was achieved by participants, given that they had no problem in recognizing that the person in the just condition is extremely good, and indeed equally as good as the person in the compassion condition, just as was expected. Moreover, the study explicitly satisfies a number of Hume’s requirements for obtaining accurate aesthetic judgments, and we have no reason to think that it violates those that cannot be demonstrably met by the study (such as it is), with perhaps the exception of the requirement for judges to have perfected their aesthetic capabilities by making comparisons. To give a few examples: participants who failed the attention check were excluded (and so they paid ‘due attention’, as Hume [Citation1757: 232] requires); the information given to participants was highly controlled across conditions, and participants were presented with information about anonymous people in all three conditions (and so it is likely that the results are free from ‘prejudice’, as Hume [ibid.: 239–43] requires); and the judgments were provided by a large number of participants from across the United States online (with online samples, and especially samples from Prolific, tending to be more demographically diverse: see, e.g., Peer et al. [Citation2017]) and the judgments comported with those of philosophers—such as Kant and Burke—living in different countries and in a different age (and so they seem to be ‘durable’, as Hume [Citation1757: 233] requires).

11 The idea that emotions are perceptions is defended by, e.g., Prinz [Citation2004] and Tappolet [Citation2016]; and it has been shown by, e.g., Yipp [Citation2021] to be robust against a number of the objections that have been levelled against it.

12 This is so, even if we first need to engage in reasoning in order to come to understand how explanatory theories unify seemingly disparate phenomena and thereby come to apprehend their beauty.

13 Thus, Hume’s claim that ‘beauty, whether moral or natural, is felt, more properly than perceived’ [Citation1777: 165] is almost correct; beauty, at least of a certain kind, is perceived in so far as it is felt.

14 The argument offered here might be thought to leave unpersuaded those, such as Zangwill (see, e.g., [Citation2001]), who reject the idea of moral beauty on the ground that they hold that beauty is dependent on sensory perceptual properties, since arguably moral virtues do not have sensory perceptual properties even if they have evaluative perceptual properties (according to the argument offered here). That might be so. But if emotions and the more paradigmatic sensory perceptions are analogous in the ways that are important to their playing the same kind of role in our mental life—by, for example, giving us direct access to the world and particularly the way that the world appears to us (which is what seems relevant here, including for supporters of sensory dependence such as Zangwill)—then why think that any disanalogies render necessary only the more paradigmatic sensory perceptual properties? Why, for example, would the fact that the more paradigmatic sensory perceptual properties, but not the evaluative perceptual properties, have proprietary sensory transduction organs (e.g. eyes) make for a relevant difference with respect to the ability of objects with these kinds of properties to be beautiful? Indeed, as we have seen, the fact that emotions can take a variety of kinds of sensory and non-sensory inputs is consistent with beauty being found in at least audible and visible objects—and, arguably, in objects of thought, too. (Thanks to a reviewer for pressing me to consider views such as Zangwill’s.)

15 I am very grateful to two anonymous reviewers for this journal for their helpful comments. I would also like to thank Pekka Väyrynen and Philipp Rau for their advice on aspects of this paper, and members of Anjan Chatterjee’s lab at the University of Pennsylvania, to whom a version of this paper was presented, for their comments.

References

- Adams, Robert M 2006. A Theory of Virtue: Excellence in Being for the Good, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Algoe, Sara, and Haidt, Jonathan 2009. Witnessing Excellence in Action: The ‘Other-Praising’ Emotions of Elevation, Gratitude, and Admiration, The Journal of Positive Psychology 4/2: 105–27.

- Bannister, Scott 2019. Distinct Varieties of Aesthetic Chills in Response to Multimedia, PLOS ONE 14/11: e0224974.

- Bateson, Gregory 1958. Naven: A Survey of the Problems Suggested by a Composite Picture of the Culture of a New Guinea Tribe Drawn from Three Points of View (Second Edition), Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Beardsley, Monroe C. 1981. Aesthetics: Problems in the Philosophy of Criticism, 2nd edn, Indianapolis: Hackett.

- Bell, Clive 1914. Art, London: Chatto & Windus.

- Burke, Edmund 1757 (1990). A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, ed. A. Phillips, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cotter, Katherine N., Alyssa N. Prince, and Alexander P. Christensen 2019. Feeling like Crying when Listening to Music: Exploring Musical and Contextual Features, Empirical Studies of the Arts 37/2: 119–37.

- Diessner, Rhett, Rebecca D. Solom, Nellie K. Frost, and Lucas Parsons 2008. Engagement with Beauty: Appreciating Natural, Artistic and Moral Beauty, The Journal of Psychology 142/3: 303–32.

- Doran, Ryan P. 2021. Moral Beauty, Inside and Out, Australasian Journal of Philosophy 99/2: 396–414.

- Doran, Ryan P. forthcoming a. Ugliness Is in the Gut of the Beholder, Ergo: An Open-Access Journal of Philosophy.

- Doran, Ryan P. forthcoming b. Aesthetic Animism, Philosophical Studies.

- Foot, Philippa 1978. Virtues and Vices and Other Essays in Moral Philosophy, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Foot, Philippa 2001. Natural Goodness, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Gaut, Berys 2007. Art, Emotion and Ethics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Haidt, Jonathan 2000. The Positive Emotion of Elevation, Prevention & Treatment 3/3: 1–5.

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd edn, New York: Guildford Press.

- Hume, David 1739–40 (1978). A Treatise of Human Nature, 2nd edn, ed. L.A. Selby-Bigge and P.H. Nidditch, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hume, David 1757 (1987). Essays Moral, Political, Literary, ed. F. Miller, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

- Hume, David 1777 (1975). Enquiries Concerning Human Understanding and Concerning the Principles of Morals, 3rd edn, ed. P.H. Nidditch, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hursthouse, Rosalind 1999. On Virtue Ethics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hutcheson, Francis 1725 (2021). Inquiry Into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue, ed. W. Leidhold, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

- Kant, Immanuel 1764 (2011). Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime, ed. P. Frierson and P. Guyer, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Landis, Shauna K., et al. 2009. The Relation between Elevation and Self-Reported Prosocial Behaviour: Incremental Validity over the Five-Factor Model of Personality, The Journal of Positive Psychology 4/1: 71–84.

- Laski, Marghanita 1961. Ecstasy: A Study of Some Secular and Religious Experiences, London: The Cressett Press.

- Lipps, Theodor 1903. Ästhetik: Psychologie des Schönen und der Kunst: Grundle-gung der Ästhetik, Hamburg and Liepzig: Leopold Voss.

- Maruskin, Laura A., Todd M. Thrash, and Andrew J. Elliott 2012. The Chills as a Psychological Construct, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 103/1: 135–157.

- McGinn, Colin 1999. Ethics, Evil, and Fiction, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Miller, David (2017). Justice, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. E.N. Zalta, URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2017/entries/justice

- Nabokov, Vladmir 1959. On a Book Entitled ‘Lolita’, Encounter 12/4: 73–6.

- Ortolani, Benito 1990. The Japanese Theatre: From Shamanistic Ritual to Contemporary Pluralism (Revised Edition), Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Paris, Panos 2018a. The Empirical Case for Moral Beauty, Australasian Journal of Philosophy 96/4: 642–58.

- Paris, Panos 2018b. On Form, and the Possibility of Moral Beauty, Metaphilosophy 49/5: 711–29.

- Paris, Panos 2020. Functional Beauty, Pleasure, and Experience, Australasian Journal of Philosophy 98/3: 516–30.

- Parsons, Glenn and Allen Carlson 2008. Functional Beauty, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Passmore, John 1951. The Dreariness of Aesthetics, Mind 60/239: 318–35.

- Peer, Eyal, Laura Brandimarte, Sonam Samat, and Alessandro Acquisti 2017. Beyond the Turk: Alternative Platforms for Crowdsourcing Behavioural Research, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 70: 153–63.

- Plato c.370 BC (1875). Phaedrus, in The Dialogues of Plato, Vol. II, trans. B. Jowett, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Prinz, Jesse J. 2004. Gut Reactions: A Perceptual Theory of Emotions, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Scarry, Elaine 2006. On Beauty and Being Just, London: Gerald Duckworth.

- Stevens, James P. 2002. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 4th edn, Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

- Tappolet, Christine 2016. Emotions, Values, and Agency, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tsubaki, Andrew T. 1971. Zeami and the Transition of the Concept of Yūgen: A Note on Japanese Aesthetics, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 30/1: 55–67.

- Wordsworth, William 1811-12 (1974). The Sublime and the Beautiful, in The Prose Works of William Wordsworth, Vol. 2, ed. W.J.B. Owen and J. Worthington Smyser, Oxford: Clarendon Press: 349–60.

- Yip, Brian 2021. Emotions as High-Level Perceptions, Synthese 199: 7181–201.

- Zagzebski, Linda T. 1996. Virtues of the Mind: An Inquiry into the Nature of Virtue and the Ethical Foundations of Knowledge, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zangwill, Nick 2001. The Metaphysics of Beauty, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Zickfeld, Janis H., et al. 2018. Kama Muta: Conceptualizing and Measuring the Experience Often Labelled Being Moved Across 19 Nations and 15 Languages, Emotion 19/3: 402–24.

- Zickfeld, Janis H., Patrícia Arriaga, Thomas W. Schubert, and Beate Seibt 2020. Tears of Joy, Aesthetic Chills and Heartwarming Feelings: Physiological Korrelates of Kama Muta, Psychophysiology 57/12: e13662.