Increased pressure on natural resources is expressed globally through land degradation, biodiversity decline and global climate change. In response to recognition that these challenges must be addressed, there are growing expectations from across society for better environmental accounting and reporting from enterprises, which are increasingly regarded as key actors in modern decentralised environmental governance (Lemos & Agrawal Citation2006). Consumers and investors have joined regulators and communities in seeking assurances that enterprises are operating sustainably.

Forestry has the potential to exacerbate or mitigate these global challenges, depending on how it is managed. The environmental and social impacts of unsustainable forestry are well understood (IPBES Citation2019). However, the right forest in the right place can enhance environmental outcomes (Bastin et al. Citation2019; Paudyal et al. Citation2020) and provide pathways for improving the livelihoods of rural and regional communities (Nambiar Citation2019). Forestry fundamentally depends on natural resources such as clean air, water, soils and biodiversity to generate economic and social benefits, and access to these resources is threatened by the same global challenges. To address societal expectations, the industry must rise to the challenge of accounting for and reporting on its impacts and dependencies as well as the benefits in a clear and transparent manner.

The two-way relationship between business and the environment is increasingly viewed through the lens of natural capital (Schumacher Citation1973; Pearce Citation1988), which has in turn led to a proliferation of frameworks for corporate natural capital assessment, valuation, accounting, disclosure and risk assessment (NCC Citation2016; CDSB Citation2018; Ascui & Cojoianu Citation2019; Barker Citation2019; ISO Citation2019). There is growing interest in the forest industry in applying these concepts and frameworks. Here we introduce some basic concepts, highlight potential opportunities and outline the challenges for broader adoption within the industry.

What is natural capital?

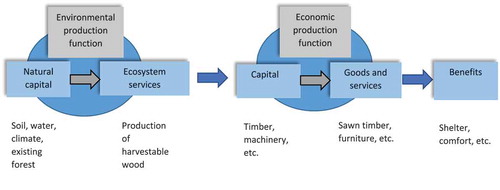

The term ‘natural capital’ conceptualises nature as a set of assets: stocks of renewable resources such as clean air, water, soil and living things, as well as non-renewable resources such as minerals and fossil fuels. These natural capital assets produce flows of ecosystem services that have value because they benefit society. Some ecosystem services (such as clean air) benefit us directly, but often they are combined with other forms of capital (e.g. manufactured or human capital) in the economy to produce traditional economic goods and services, as illustrated in . The flows of ecosystem services are dependent on both the amount (or extent) and condition of the natural capital stock (Hein et al. Citation2015). Natural capital accounting is the process of measuring changes in the stocks and condition of these assets and associated flows.

Figure 1. Natural capital as an input into economic production (adapted from Binner et al. Citation2017)

Conceptually, natural capital is similar to other forms of capital. However, the value of the ecosystem services provided by natural capital assets is dependent on the spatial location in which they are produced. For example, the value of clean water services provided by forests depends on their location relative to downstream households and businesses, recreation services depend on proximity to populations and biodiversity services depend on the surrounding habitats and their configuration and connectivity. Although the value of economic goods and services can be linked to the location of the production, this is much less common than for ecosystem services.

Some natural capital assets are capable of repair and regeneration without the intervention of humans. The capacity for regeneration is a central feature of renewable natural capital and can be enhanced or eroded by human activity.

The substitutability of natural capital with other forms of human or manufactured capital has implications for the sustainability of economic development. Current evidence suggests that many natural capital assets cannot plausibly be substituted by other forms of capital. Hence, caution should be applied in activities that irreversibly degrade natural capital (Cohen et al. Citation2019).

Implications for business

Natural capital thinking encourages businesses to think beyond the scope of the economic production function illustrated in to consider their more fundamental dependencies on the environmental production functions provided by nature. This complements the more familiar imperative to consider business impacts on the environment as externalities—that is, as outside the scope of the economic production function until incorporated due to regulatory, consumer or other stakeholder pressure.

These considerations have implications for how companies manage their operations, configure their supply chains, identify strategic opportunities and risks, make investment decisions, and account for and report on their activities to shareholders and other stakeholders. As a result, a plethora of natural capital business applications has been developed in recent years, with over 40 initiatives launched up to 2015 (Santamaria & Gough Citation2017). This can create confusion. An important starting point, therefore, is to recognise that natural capital accounting, like carbon accounting (Ascui & Lovell Citation2011), means different things to different people (Barker Citation2019).

Nevertheless, there is gradual convergence on standardised approaches to certain applications. For example, the Natural Capital Protocol (NCC Citation2016) provides a generic framework for businesses to identify their interests in natural capital then measure and value what is relevant without prescribing how such measurement and valuation should be done or how it should be used or disclosed. The United Nations System of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA) standard (UN Citation2014a,Citationb) was adopted for national-level statistical reporting in 2012, providing a framework for measuring and valuing natural capital stocks and ecosystem service flows associated with specific land areas (Hein et al. Citation2015). Although its application at enterprise scales is at an early stage, SEEA can be adapted for forest enterprises more easily than most other types of business due to the direct association with specific land areas.

Other corporate accounting frameworks also exist (Barker Citation2019). An international standard on monetary valuation of environmental impacts has been published (ISO Citation2019), and the Natural Capital Finance Alliance has developed methods and tools for natural capital opportunity and risk assessment (NCFA & PwC Citation2018; NCFA & UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre Citation2018; Ascui & Cojoianu Citation2019). Finally, the Climate Disclosure Standards Board has published a framework to guide corporate reporting of natural-capital-related information (CDSB Citation2018).

Implications for forestry

The breadth of types of natural capital and the complexity of interactions with a given enterprise can be daunting. However, a materiality assessment of an organisation’s impacts and dependencies on natural capital can assist this effort (NCC Citation2016). The Natural Capital Protocol and the Natural Capital Finance Alliance provide guidance for conducting such assessments (Ascui & Cojoianu Citation2019). Materiality assessments recently carried out for the Australian forest industry (O’Grady et al. Citation2020; Smith et al. Citation2020b) demonstrated that forestry has a high materialFootnote1 dependency on natural capital. Thus, forestry’s financial outcomes are strongly dependent on the flows of ecosystem services derived from its natural capital base.

Opportunities

Building capacity to account for and value the natural capital under management can help forest owners understand how to improve yields and sustain the productivity of their natural capital into the future. Natural capital accounting also offers other opportunities, such as the following:

It can help maintain social licence through improved communication with key stakeholders about the sector’s natural capital impacts, benefits, dependencies and risks.

Market-based instruments linked to natural capital are becoming increasingly common and can open up new finance models for the industry (Smith et al. Citation2020a). Emerging opportunities may be linked to regulatory, investor or consumer demand for natural capital targets or outcomes, such as carbon credits and biodiversity stewardship payments.

Opportunities for large-scale industrial forestry, in particular, relate to the rapid growth in responsible investment, leading to demand for new privately owned sustainable forestry assets that have positive natural capital impacts over and above economic returns (GIIN Citation2019).

For publicly owned and managed forests, there is potential to issue green bonds for improved natural capital management.

Interventions aimed at small-scale private native forest owners could also have a large cumulative impact, although such interventions would typically require some degree of government or philanthropic support, possibly combined with new revenue streams from environmental markets.

Other examples of emerging opportunities include working forest conservation covenants; developing an Australian Forest Resilience Bond; increased public funding for forest natural capital management; collaborative funding approaches to achieve landscape-level outcomes (e.g. fire management); blended finance; new environmental markets; and sustainability-linked loan schemes (Smith et al. Citation2020a). Many of these natural capital finance mechanisms already exist; the key challenge for the Australian industry in realising these is identifying and developing the projects that match the expectations and desired outcomes of the various mechanisms.

The Australian forest industry has plans for significant expansion. Due to climate change, this expansion will be in environments likely to be warmer and drier in the future, where access to natural capital is increasingly contested. Building capacity within the forest industry to recognise and account for these dependencies will better position the industry for the challenges associated with operating in a highly uncertain future. Increasingly, investors, lenders and other stakeholders will require disclosure of natural capital risks. Natural capital accounting and risk assessment can help address these concerns, using approaches that link to existing financial reporting and disclosure obligations.

Challenges

Although there is interest and growth in the opportunities, there are also challenges ahead. Overall awareness of natural capital is reasonably high in the forest industry, building on the industry’s long history of environmental management and sustainability certification, but detailed understanding of the underlying concepts and processes is relatively low (O’Grady et al. Citation2020). Broader uptake will require an investment in capability as well as a coordinated approach within the industry to ensure the alignment of and consistency in approaches. Making the case for such investment will be difficult in the absence of a clear value proposition grounded in case studies led by the industry.

Measurement is also an important gap. Many players in the industry already invest considerably in environmental compliance and reporting, but the opportunity to streamline this through natural capital accounting remains relatively unexplored. Although it may be true that ‘you can’t manage what you don’t measure’, deciding what to measure, when and how are all important considerations in the adoption of natural capital accounting. Recent research provides guidance to help with these decision points (O’Grady et al. Citation2020; Smith et al. Citation2020b), but broader application and standardisation across the industry is required.

As we have discussed, there is growing convergence on a smaller number of methods and standards for different natural capital business applications. However, there is still a dearth of methods and standards that are specifically relevant to the key conceptual challenges facing the forest industry, such as ecosystem condition accounting and the measurement or modelling of environmental services. Furthermore, application and use cases at an enterprise scale are relatively few.

Finally, increased revenue associated with payments for ecosystem services is often cited as a key opportunity associated with natural capital accounting. But there remains a lack of developed markets and thus buyers for ecosystem services. Although natural capital markets and finance are expanding rapidly, the development of projects capable of delivering additional environmental outcomes and required investment returns remains challenging.

Conclusion

The forest industry is increasingly interested in the opportunities associated with better recognition and management of natural capital. These opportunities undoubtedly lie at the intersection of the growing demand for ecosystem services, sustainably produced resources and finance instruments linked to natural capital outcomes such as halting and reversing global land degradation, biodiversity loss and greenhouse gas emissions. But natural capital thinking and accounting can play a critical role in helping forestry enterprises identify and adapt to changes in the supply of ecosystem services associated with changing climates and competing demands for shared natural capital. A coordinated approach to natural capital management and an outcomes focus underpinned by credible, robust measures will help build the value propositions to support the forest industry’s planned expansion over the next decade. Natural capital thinking and natural capital accounting could shift the forest industry from a compliance modus operandi to one focused on proactive management and protection of the very natural capital that will ensure the industry’s long-term sustainability and viability.

Acknowledgements

Our natural capital research program is generously supported by the Australian Government’s Rural Research for Development and Profit Program − Lifting Farm Gate Profits: the Role of Natural Capital Accounts (RnD4P-16-03-003) and the National Institute for Forest Products Innovation: Unlocking Financial Innovation in Forest Products with Natural Capital (NT011).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ‘Information is material if its omission, misstatement or non-disclosure has the potential to adversely affect:

(a) decisions about the allocation of scarce resources made by users of the financial report; or

(b) the discharge of accountability by the management or governing body of the entity.’ (AASB Citation1995)

References

- AASB. 1995. Materiality. Melbourne (Australia): Australian Accounting Standards Board; p. 18.

- Ascui F, Cojoianu T. 2019. Natural capital risk assessment in agricultural lending: an approach based on the natural capital protocol. Oxford (UK): Natural Capital Finance Alliance.

- Ascui F, Lovell H. 2011. As frames collide: making sense of carbon accounting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal. 24(8):978–999. doi:10.1108/09513571111184724.

- Barker R. 2019. Corporate natural capital accounting. Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 35:68–87. doi:10.1093/oxrep/gry031.

- Bastin J-F, Finegold Y, Garcia C, Mollicone D, Rezende M, Routh D, Zohner CM, Crowther TW. 2019. The global tree restoration potential. Science. 365:76–79. doi:10.1126/science.aax0848.

- Binner A, Smith G, Bateman I, Day B, Agarwala M, Harwood A. 2017. Valuing the social and environmental contribution of woodlands and trees in England, Scotland and Wales. Edinburgh (UK): Forestry Commission.

- CDSB. 2018. CDSB Framework for reporting environmental information, natural capital and associated business impacts. London (UK): Climate Disclosure Standards Board.

- Cohen F, Hepburn CJ, Teytelboym A. 2019. Is natural capital really substitutable? Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 44:425–448.

- GIIN. 2019. Scaling impact investment in forestry. New York (NY): Global Impact Investing Network.

- Hein L, Obst C, Edens B, Remme RP. 2015. Progress and challenges in the development of ecosystem accounting as a tool to analyse ecosystem capital. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 14:86–92.

- IPBES. 2019. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn (Germany): IPBES Secretariat.

- ISO. 2019. ISO 14008: 2019. Monetary valuation of environmental impacts and related environmental aspects. Geneva (Switzerland): International Organization for Standardization.

- Lemos MC, Agrawal A. 2006. Environmental governance. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 31:297–325. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.31.042605.135621.

- Nambiar EKS. 2019. Tamm review: Re-imagining forestry and wood business: pathways to rural development, poverty alleviation and climate change mitigation in the tropics. Forest Ecology and Management. 448:160–173. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2019.06.014.

- NCC. 2016. Natural capital protocol. London (UK): Natural Capital Coalition.

- NCFA and PwC. 2018. Integrating natural capital in risk assessments: a step-by-step guide for banks. Geneva (Switzerland), Oxford and London (UK): Natural Capital Finance Alliance and PricewaterhouseCoopers.

- NCFA and UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre. 2018. Exploring natural capital opportunities, risks and exposure: a practical guide for financial institutions. Geneva (Switzerland), Oxford and Cambridge (UK): Natural Capital Finance Alliance and UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

- O’Grady AP, Pinkard EA, Mount R, Schmidt B, Cresswell I, Stewart S. 2020. Conceptual modelling to support natural capital accounting of a forestry enterprise. Hobart (Australia): CSIRO Land and Water.

- Paudyal K, Samsudin YB, Baral H, Okarda B, Phuong VT, Paudel S, Keenan RJ. 2020. Spatial assessment of ecosystem services from planted forests in Central Vietnam. Forests. 11:822. doi:10.3390/f11080822.

- Pearce DW. 1988. Economics, equity and sustainable development. Futures. 20(6):598–605. doi:10.1016/0016-3287(88)90002-X.

- Santamaria M, Gough M. 2017. Combining forces on natural capital. London (UK): Natural Capital Coalition.

- Schumacher EF. 1973. Small is beautiful: a study of economics as if people mattered. New York (NY): Harper & Row.

- Smith GS, Ascui F, O’Grady AP, Pinkard EA. 2020a. Opportunities for natural capital financing in the forestry sector. Hobart (Australia): CSIRO Land and Water.

- Smith GS, Ascui F, O’Grady AP, Pinkard EA. 2020b. Forest natural capital risk assessment. Hobart (Australia): CSIRO Land and Water.

- UN. 2014a. System of environmental-economic accounting 2012 − experimental ecosystem accounting. New York (NY): United Nations.

- UN, et al. 2014b. System of environmental-economic accounting 2012: central framework. New York (NY): United Nations.