ABSTRACT

The harvest and trade of sandalwood (Santalum macgregorii) from natural stands began in Papua New Guinea (PNG) in the late nineteenth century. Sporadic harvesting has occurred intermittently since then and continues to this day, with little active management to promote regeneration. This study was undertaken to determine the state of natural sandalwood resources in PNG, clarify the associated regulations for monitoring its trade and export, and identify practical options for local resource restoration through family and clan plantings. We studied export permit data, interviewed resource owners and traders, evaluated forestry legislation and regulation and engaged landowners in three areas of the country to establish sandalwood plantings. We found few regulations or monitoring protocols for sandalwood harvesting and trade in PNG. Export declarations are the only means for reporting the grades and volumes traded. There is evidence that both grades and prices have been underdeclared at point of export. No export permits in the last eight years contained records of any high-grade (A) products, and declared export values were lower than domestic prices paid to resource owners. Export records since 1997 reveal that significant volumes of up to 126 tonnes annually were traded in the early 2000s. The natural resource is yet to fully recover, with much lower volumes exported.

To address the reduction in availability of natural sandalwood, we engaged landowners in three locations to establish sandalwood plantings. The results demonstrate that sandalwood, grown in agroforestry systems, can be productive in PNG, with mean basal stem diameter increments of up to 2.0 cm y−1 recorded. To further develop the sandalwood sector in PNG, we make four recommendations: (1) establish a ten-year moratorium on the sandalwood trade to enable the recovery of natural populations; (2) develop a product grading and sales registry system to improve trade transparency and monitoring; (3) reallocate the tax revenues generated from sandalwood exports to the PNG Forest Authority to fund the monitoring of harvesting and trade; and (4) promote options for resource restoration through family garden, boundary and enrichment plantings. The sandalwood industry in PNG has the potential to be viable and sustainable if the proposed recommendations are adopted by appropriate stakeholders to manage production and regulate the trade in the country and internationally.

Introduction

Sandalwood (Santalum macgregorii F.Muell.) grows naturally in the south-west region of Papua New Guinea (PNG), particularly in the lowland areas of Gulf and Central provinces (). There are also small isolated populations in the Buzi and Ber areas of Western Province. In these areas, S. macgregorii occurs naturally in habitats ranging from open eucalypt woodlands to savannah grasslands at altitudes from 3 m above sea level (ASL) in Gulf Province to as high as 800 m ASL in the Varirata National Park in Central Province (Bosimbi Citation2005; Bosimbi & Bewang Citation2007). The valuable fragrant oil contained mainly in the heartwood of this species (Brophy et al. Citation2009) provides the basis for its harvesting and trade (Thomson Citation2020).

Figure 1. Map of Papua New Guinea showing the area (shaded) where Santalum macgregorii grows naturally as well as the locations of trial plots for this study

The harvesting of S. macgregorii in PNG dates to the late nineteenth century and has continued intermittently ever since. In more recent decades, there have been reports of sporadic overharvesting (Paul Citation1990; Kiapranis Citation2006), leading to the species becoming rare in the wild (Page, Jeffrey et al. Citation2020). Despite this, the trade in sandalwood continues today, with stands harvested in parts of Kairuku-Hiri District in Central Province and in Gulf Province due to increased accessibility from improved road networks. Most areas in Central Province no longer trade S. macgregorii due to the depleted stock of mature trees. Because of the overharvesting and a lack of silvicultural management, there is an urgent need for interventions to better ensure the sustainable production and supply of sandalwood in PNG.

Interest in sandalwood development in PNG flourished in the 1960s and 1970s, when the extension service of the National Forest Service was active throughout the country. In that era, community extension services assisted local communities to plant trees for a variety of end uses. The establishment of woodlots for minor forest products such as sandalwood was limited, however, with a greater focus on harvesting in natural stands. In areas where resources had declined, communities and landowners expressed interest in conserving and restoring their local sandalwood. In subsequent years, little external assistance was provided to encourage farmers and resource owners to manage their existing stands or develop new sandalwood resources (Kiapranis Citation2006). Despite this, there is considerable potential for landowner-led sandalwood restoration in PNG, similar to what has occurred in other Pacific Island countries (Bush, Thomson et al. Citation2020; Page, Doran et al. Citation2020).

Recent studies of oil properties in S. macgregorii have demonstrated remarkable variation between individual trees (Brophy et al. Citation2009; Page, Jeffrey et al. Citation2020). For the two most important fragrant compounds, α- and β-santalol, trees ranged from negligible amounts to very high levels that meet the international standard for Santalum album L. (ISO Citation2002). Similar variation was also found between trees for many other compounds. This variation influences the generally lower market perception of PNG sandalwood compared with other Pacific species (Thomson Citation2020). The mean levels of α- and β-santalol in S. macgregorii found by Page, Jeffrey et al. (Citation2020) were lower than their respective levels in Santalum yasi Seem. from Fiji and Tonga (Bush, Brophy et al. Citation2020) and S. album in Australia (planted) and Sri Lanka (Brand et al. Citation2012; Subasinghe et al. Citation2017). For Santalum austrocaledonicum Vieill., much variation in the level of santalol was found within and between sites in Vanuatu, but several sites in both Vanuatu and New Caledonia demonstrated higher santalol levels, equivalent to S. album (Braun et al. Citation2005; Page et al. Citation2010; Butaud Citation2015) and higher than any S. macgregorii population. PNG sandalwood has comparatively higher levels of α- and β-santalol than Santalum lanceolatum R.Br. in northern Australia (Page et al. Citation2007) and Santalum spicatum (R.Br.) A.DC. in Western Australia (Moretta Citation2001).

In this paper, we evaluate the current state of the natural sandalwood resource in PNG and associated regulations for monitoring its trade and export. We also explore interventions conducted by the PNG Forest Authority (PNGFA) under an Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR)-funded project (FST/2014/069) to stimulate sandalwood replanting in three key areas: (1) Iokea (Gulf Province); (2) Kairuku (Central Province); and (3) Girabu (Central Province). These key areas are strategically located within the natural distribution of sandalwood in PNG ().

Methods

To review the history and potential development of the sandalwood sector in PNG, we collated and summarised sandalwood export records to determine volumes traded; interviewed 12 previous and current sandalwood resource owners, six traders and two exporters to understand the supply chain as well as the grading standards used and prices paid; reviewed national forestry legislation and regulations as they relate to the management of sandalwood; and established and measured smallholder participatory sandalwood demonstration plantings in three communities.

We present and discuss the results from these analyses and interviews in the form of a report on: the status of sandalwood in PNG; a summary of trade regulations; community sandalwood initiatives; and developing a sustainable sandalwood sector in PNG.

Status of sandalwood in Papua New Guinea

Local scenario

The high demand for PNG sandalwood (S. macgregorii) in Asian markets due to its fragrant wood and high essential-oil content has resulted in its depletion in natural stands. Human population growth and an associated increase in grassland burning have further contributed to sandalwood decline. The depletion of sandalwood in natural stands has resulted in a loss of income for many landowners who have depended on sandalwood to supplement their income. For decades, sandalwood has been an important source of revenue for many rural communities where it grows naturally, helping improve the livelihoods of the local people.

With continued exploitation, it is possible that mature stands of sandalwood will no longer support natural regeneration and recruitment. Although there is evidence of landholders engaging in assisted natural regeneration (Page, Jeffrey et al. Citation2020), the lack of a more coordinated approach to community forest management has contributed to the unsustainable harvesting of S. macgregorii by local communities. This overexploitation and associated issues of supply have likely reduced export earnings by the sandalwood industry in PNG, which is entirely dependent on the species’s natural stands. This situation has and will continue to affect people in rural communities who rely on its production and trade to generate income for their day-to-day livelihoods.

National scenario

Although PNG has never undertaken an inventory of its natural sandalwood resource, records indicate that harvesting began in the late 1800s. According to an estimated 9000 tonnes of sandalwood were harvested between 1891 and 1980. This equates to an estimated 100 tonnes y−1 over a period of 90 years, although harvesting occurred intermittently during that time. In 1994, the PNGFA established the Forest and Log Export Monitoring System in PNG, but sandalwood was not included. Between 1997 and 2019, a total of 532 tonnes was exported, giving an income of USD 792 000 (equivalent to USD 34 435 y−1, with an average price of USD 1489 tonne−1).

The spike in sandalwood exports from PNG in the early 2000s () came about as a result of improved road access and competitive pricing. Local villagers in Central and Gulf provinces, where sandalwood occurs naturally, refer to this period as the ‘sandalwood rush’. Many local communities harvested mature sandalwood trees of high quality during this period. PNG’s sandalwood export quantities were low in 2013 and 2015 but fetched high prices equivalent to A-grade sandalwood (e.g. USD 12.87 kg−1 and USD 13.86 kg−1, respectively). Given that no A-grade product was declared in those years, it is unclear why there was such a high unit value for free on board, demonstrating the need for greater scrutiny of the supply chain by the PNGFA. Also, it is noted that the higher prices since 2013 may be due to the low abundance of natural sandalwood but continuing high demand. The increase in PNG sandalwood exports in 2012 and 2019 was the result of Asian buyers purchasing directly from resource owners in local communities. The 24.3 tonnes exported in 2012 and the 19 tonnes traded in 2019 were, however, substantially less than the volumes traded between 2000 and 2005 (mean 62.9 tonnes; ). There were nil exports in 2009 and 2014, respectively, due to no production and trade in the country. The small volume of sandalwood (397 kg) exported in 2017 was used to promote PNG sandalwood to buyers in the Asian region. It is most likely that natural sandalwood resources have not fully recovered from the high volumes harvested in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Sandalwood trade regulations in Papua New Guinea

Harvesting and logistics

Sandalwood trees are harvested and sorted by landowners at the village level. Usually, the entire tree is uprooted and semi-processed (i.e. debarked and desapped). This process is conducted manually (using bush knives and axes) in the forest at the site of harvest or within the village. During the 2000s, when multiple landowners were selling sandalwood, buyers and their agents would purchase directly from resource owners in villages (i.e. farm gate). Purchases were made from individuals rather than from groups aggregating logs into one sale.

Today, only small volumes of sandalwood are traded by a small number of landowners, who take their sandalwood logs directly to exporters in Port Moresby. Typically, the semi-processed sandalwood is transported by public motor vehicles (PMVs) from the communities at a cost dependent on the estimated value of the product and the distance of travel—no consideration is given to volume or weight. For example, from Kairuku to Port Moresby, a distance of 120 km, the rate per person is USD 8.71Footnote1 plus 10–20% cost of the value of the product transported. For sandalwood worth USD 290, the PMV cost could be USD 29–58. The sale (including the cost of transport) is completed once the sandalwood products are brought to the buyers/exporters. All PMV transport operations are privately owned by locals who do not have business links with the sandalwood buyers/exporters in the country.

Grading and pricing

The grading and pricing of sandalwood harvested in PNG is controlled and determined by the buyers/exporters operating in the country. The PNGFA, as the regulating government agency, does not have a standard grading or pricing system for this minor forest product. Because there are no national standards, the buyers/exporters have developed their own grading and pricing system based on three criteria () dependent on product type, form and size (length and diameter). There are four product grades: (A) sound logs; (B) logs with defects and roots; (C) branches and twigs; and (D) dust (chips). A log-form product type at the point of sale with a length equal to or greater than 50 cm and a diameter equal to or greater than 30 cm can fetch a price ranging from USD 7 kg−1 to USD 15 kg−1. Deformed or defective logs with a diameter of less than 30 cm are usually sold for less than USD 6 kg−1. Smaller product types (i.e. branches, roots and twigs) sell for USD 3–6 kg−1.

Table 1. Sandalwood grading system in Papua New Guinea developed by buyers/exporters

The demand for and price of these products are influenced by the preferences of individual buyers based on their export market requirements. Villagers carry out semi-processing, and buyers undertake further processing to meet the specifications and requirements of the overseas buyers. Some heartwood is reprocessed by exporters in PNG into chips and dust.

Regulation and export

There are records of sandalwood being regulated in the Territory of Papua in the early 1900s, according to the Timber Ordinance 1909–1920 (LCTP 1909). The Ordinance called for a timber permit to allow for the harvest and trade of sandalwood on both Crown and Native-owned land. It also specifically detailed its harvest measurements at a height of one foot (30 cm) from the surface of the ground the stem circumference is equal to or greater than 18 inches (45.7 cm), debarking and stacking (within three months of harvest), marking (legibly marked and branded with figures and letters of dates felled and the initials of the person by whom it was felled), and the licence (to cut, collect and buy from the local clans).

There are formal processes under the amended Forestry Act 1991 that landowners and traders can use when harvesting minor forest products. The legal documents required by companies dealing and trading with minor forest products such as sandalwood in PNG include: a certificate of company registration through the PNG Investment Promotion Authority; a forest industry participant (FIP) certificate from the PNGFA; a licence (PNGFA) and a timber authority (TA-04) (PNGFA) to operate over a period of one year. Even though both a TA-04 and a licence are required to operate, it was found that all participants were issued with only licences. The basis for waiving the requirement for a TA-04 includes: the scarcity of the sandalwood population in natural stands; the resource and harvesting rights resting with the landowners, with no clear documentation of ownership and boundaries (required for a TA-04); and it is not financially feasible because the returns associated with sandalwood trade would not cover the cost of the process and fees involved with the TA. Given this scenario, resource owners are harvesting their sandalwood and selling directly to traders. This makes it impossible for the government to monitor the volumes harvested in natural stands because there is no record of the areas from which the wood is originating or the volume harvested and exported.

Many minor forest products are scarce and located in isolated areas over a wide geography. For these reasons, the PNGFA issues blanket licences to any FIPs for the purchase and sale of all minor forest products across the provinces in which they seek to operate for a period of one year. For example, an FIP issued with a blanket licence can purchase and make sales of sandalwood, massoi (Cryptocarya massoy R.Br.), eaglewood (Gyrinops ledermannii Domke) and others in Central, Morobe and even Sandaun province within a given year. The performance bond for this type of licence is PGK 50 000. In 2015, the PNGFA adjusted its licence system for minor forest products (except massoi, which remains under the blanket licence), where trading is confined to particular provinces or production areas. These licences cover the purchase of a single species for a defined production area or province for a calendar year. Under this revised licence system, the performance bond for sandalwood alone is PGK 5000.

After the sandalwood products have been purchased and reprocessed according to overseas market requirements and specifications, the exporter in PNG is required to secure an export permit. The export permit consists of the following: the exporter’s details (exporter, FIP number and licence); product details (species, quantity, value and total); shipping details (vessel name, estimated time of arrival of vessel, port of loading, destination, consignee and address); and the exporter’s signature (name and designation). The PNGFA officers carry out inspections on the declared sandalwood products for export before the export checks carried out by PNG Customs.

Records of sandalwood trade in PNG since 1997 indicate that 12 of the 16 trading companies were registered in PNG, and there were two each from Indonesia and Malaysia. The sandalwood products from PNG were mainly exported to Singapore and Taiwan Province of China, with some going to China and Indonesia. In a review of export permits issued since 2012, we found that 22% had no grading certificate, 22% were declared woodchips and waste, 11% were listed as C or D grade only, and 44% were listed as B, C and D grades. The records show that no export of A-grade sandalwood was undertaken over the period. Although this may reflect a lack of resource, anecdotal reports suggest that A-grade sandalwood is exported covertly using existing supply chains and also across the land border with Indonesia. Because there are no specific product specifications for the trade in minor forest products in PNG, exporters have complete control over grading, pricing and associated export declarations. The tax collected from exported sandalwood is 15% and is paid directly to PNG Customs.

Community sandalwood initiatives

The PNGFA consulted with the Central and Gulf Provincial governments in 2014 to identify candidate districts with remnant natural stands of sandalwood (S. macgregorii). Following these initial consultations, meetings were held in Rigo, Kairuku-Hiri and Malalaua districts, where three communities with the potential to host sandalwood plantings were identified: (1) Girabu in Rigo District; (2) Kairuku in Kairuku-Hiri District of Central Province; and (3) Iokea in Malalaua District of Gulf Province. The consultations included identifying families to participate in establishing demonstration sandalwood plantings.

Extension and training

The demonstration plantings were conducted by way of extension training delivered through partners (PNGFA, ACIAR, the Central and Gulf provincial administrations, and landowners) under an ACIAR-funded project (FST/2014/069), with in-field training addressing site preparation, planting and pruning. Two two-day training workshops were held in Iokea (40 participants from four villages) and Kairuku (95 people from six villages), covering: sandalwood products and markets; seed collection and processing; potting media; potting seedlings; nursery management; hosts; and planting establishment and management. The workshops were structured with formal lessons, group discussions and field and practical demonstrations. Additional informal extension was provided to four communities surrounding Girabu (Gobuia, Gomore, Londairi and Wasuma), combined with the distribution of over 1000 sandalwood seeds to interested growers. The extension and training activities stimulated local interest in planting sandalwood, resulting in high demand for sandalwood seeds and seedlings within these communities.

Sandalwood demonstrations

The implementation and design of the demonstration plantings was guided by discussions with the communities. This participatory approach was supported by existing scientific knowledge of sandalwood establishment and management, which was adapted to suit the situations and resources of the participants. This resulted in the adoption of different approaches for the sandalwood demonstrations in each of the three areas.

Girabu, Rigo District, Central Province

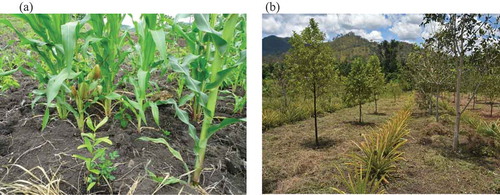

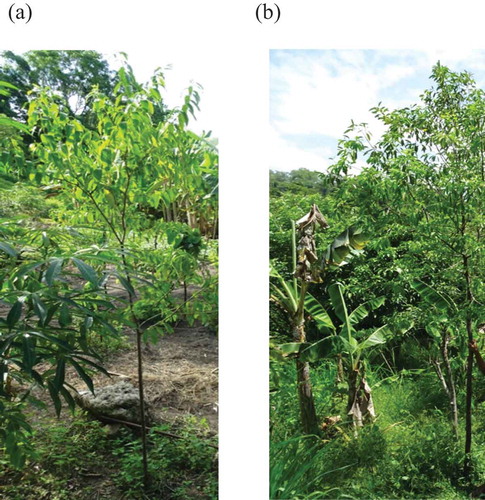

In Girabu, a 1-ha site dominated by Imperata cylindrica L. Raeusch. was allocated by a local subclan and established as an agroforestry demonstration trial plot in 2015 (). The site was mechanically ploughed and planted with rows of vegetables, fruits and root crops for the first 12 months. A nursery was constructed at the site, and sandalwood seeds were collected from local natural stands and supplemented with additional seed sourced from Kairuku and Malalaua districts. Sandalwood and host seedlings were planted in the garden site over seven months from December 2016. A total of 221 sandalwood trees were planted in 13 rows with a spacing design of 5 m × 5 m. Six rows each of Cassia fistula L. and Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit were planted, giving a total of 204 host trees. Two years after planting, sandalwood survival was 87% and mean annual increment for basal stem diameter was 2.0 cm.

Iokea, Malalaua District, Gulf Province

In Iokea, a 1-ha single-clan block was demarcated and established as a trial plot (). Sandalwood seeds were sourced from multiple trees growing in the village area. Community members established small temporary nurseries to commercially supply the project with sandalwood seedlings through a structure established by Gulf Province extension officers. The existing vegetation on the planting site was dominated by I. cylindrica but included small saplings (1–2 m) of Albizia sp., Timonius timon (Spreng.) Merr., Vitex sp. and Morinda citrifolia L. The site was slashed and grass sprayed with herbicide in rows to release the saplings to act as hosts. A total of 300 sandalwood seedlings were planted in April 2015 at a spacing of 6 m × 3 m. The site was refilled with 200 seedlings in June 2016, with additional host plants of Glyricidia sepium (Jacq.) Kunth ex Walp. planted between the sandalwood. By November 2017, the survival rate was 26%. This low rate was due to a combination of dry conditions, the re-establishment of Imperata grass (inadequate maintenance) and a fire (inadequate fire prevention and management) that burnt the site in October 2017. The mean annual increment of basal stem diameter of the surviving plants was 0.74 cm.

Kairuku project area, Kairuku-Hiri District, Central Province

Several communities, Babiko, Biotou, Eboa, Ipaipana, Mou, Nikura, Rapa and Vanuamai, were involved in sandalwood establishment in Kairuku District. In contrast to the clan-based demonstrations used in Girabu and Iokea, the Kairuku project engaged with multiple individual families. In this approach, nuclear families established sandalwood woodlots around their backyards and adjacent areas. They used the numerous sandalwood seed trees growing in household backyards or elsewhere on their land as the primary seed source. A project nursery was established in the central village of Biotou, which served as a focal point for seed sourcing, seedling production and distribution for participants in the district. Sandalwood plots were established using three planting approaches: (1) agroforestry (); (2) boundary; and (3) ornamental. These were suitable for families with limited seed sources and facilitated the maintenance of the trees and the collection of seeds. Two years after the project commenced, a survey of 35 growers found a total of 1580 seedlings planted, with the size of individual plantings ranging from 12 to 200 seedlings. The mean annual increment of basal stem diameter was 1.1 cm at age two years.

Developing a sustainable sandalwood sector in Papua New Guinea

The PNGFA and its research partners could initiate and encourage several approaches to ensure the sustainable development of S. macgregorii in PNG. This goal can only be achieved, however, through the development of a national policy that supports the conservation of remaining natural populations and the expansion of planted resources.

Regulating harvest and trade

In our review of PNG’s regulations, it was evident that little provision is made in the Forestry Act 1991 or associated policies for the trade of minor forest products such as sandalwood. Given the low volumes of sandalwood relative to the trade in large round logs of tropical hardwoods, alternative systems for independently tracking sales are required. The use of a PNGFA sales registry system that records the buyer, seller, grades, volumes, prices and geographical sources could be an effective way of monitoring the volumes traded from different areas, and it could be used to crosscheck with the grades and volumes exported.

This study identified that few PNGFA resources are allocated to the monitoring and regulation of sandalwood harvesting and trade. Although the taxes on other minor forest products are allocated to the PNGFA, those on sandalwood sales are provided to PNG Customs. If tax revenues from sandalwood were available to the PNGFA, this would provide a revenue stream to fund the regulation of the trade and improve the management of this natural resource.

It is evident that limited capacity exists for the independent verification of export declaration values. Between 2010 and 2019, a total of 193 tonnes of sandalwood was traded, with a mean value of USD 2.74 (), which is lower than the prices paid to landowners for C-grade sandalwood (). The international price is likely to be higher than that paid to landowners, suggesting that export values are being declared at or below domestic market values. The development of a nationally recognised and publicly available grading and tracking system is required to enable a more transparent trading system. This would facilitate the more accurate verification of export quantity, quality and value. It would also provide resource owners with a better understanding of different product qualities and put them in a more equitable position to negotiate prices with buyers and their agents.

Natural resource conservation

Risks to the extent and viability of natural populations of sandalwood, such as overharvesting, illegal harvesting, fire and strong winds, continue to affect the extent and viability of natural populations. Therefore, the PNGFA should consider a temporary ban (e.g. ten years) on the harvesting of sandalwood to allow its natural stands to recover and regenerate. The moratorium would allow a more formal assessment of existing resources, which could be used to establish designated areas, obtain a sustainable annual harvest volume, and develop a minimum cutting diameter limit by developing sapwood/heartwood ratios as a proxy for tree age.

There is also a need to establish a national sandalwood germplasm centre, along with nursery facilities, to support the establishment of research trials and ex situ conservation stands. Such stands are required to preserve existing genetic variation for both domestication and conservation purposes. With recent research conducted into natural variation in S. macgregorii (Page, Jeffrey et al. Citation2020), there is also an opportunity to capture and conserve improved germplasm to support the emergence of a high-value planted estate.

Sandalwood resource restoration

Our study has demonstrated that the expansion of the sandalwood resource through planting is one option for resource restoration. Sandalwood plantings in PNG can be productive at both the family level (Kairuku) and the subclan level (Girabu). The success of the subclan-managed sandalwood agroforestry plot in Girabu demonstrates the potential for scaling up sandalwood plantings. Complex social and cultural interactions at the clan level present challenges for community forestry in PNG (Baynes et al. Citation2017), which was demonstrated with the management of the sandalwood planting in Iokea. Another important underlying issue is the complexity of the process that landowner groups must pursue to legally register their land.

Sandalwood production is most applicable at the family level, where issues related to land ownership, woodlot management and benefit-sharing are simplified and can be sustainably managed at this scale. Sandalwood production is also viable when established in home gardens where hosts are readily available, thus simplifying the production process. This was demonstrated in Kairuku, where the adoption rate and number of trees planted was greater than for the two clan-based plantings. Significant investment in capacity building among landowners in the technical areas of propagation and silviculture is required, however, to scale out the benefits of family sandalwood planting. Basal stem diameter increments of young PNG sandalwood grown in the three smallholder systems ranged from 0.74 cm y−1 to 2.0 cm y−1. These growth rates compare favourably with S. album in India (0.4–0.81 cm y−1; Rai & Sarma Citation1990) and S. austrocaledonicum in Vanuatu (0.78–1.78 cm y−1; Page et al. Citation2012).

Support to develop Papua New Guinea sandalwood

To support the landowner-led restoration of sandalwood resources in PNG, further research is required to enhance germplasm diversity and quality through domestication, improve seed handling and nursery management, determine host-plant performance, optimise the spacing and layout of trees (sandalwood and hosts), improve growth rates and promote heartwood development.

To support the sustainable development of the sandalwood trade, research is needed into grading, pricing and markets. In PNG, local people are often unaware of quality considerations or the international market price for different products from sandalwood and they therefore generally accept the prices that buyers offer. In some cases (in the belief that this is the best price), locals have overharvested their natural stocks, and it has also led to illegal (over)harvesting.

Nationally, the PNGFA and other relevant government agencies, including provincial and district administrations, need to make information on sandalwood readily available to resource owners and the public. Interested sandalwood growers in communities need to be identified and trained so they can act as advocates for sandalwood in their own villages. Model site nurseries should be upgraded and better resourced by the PNGFA and respective provincial governments to support such advocates and the communities involved. Collaboration among all sectors, including provincial, district and local governments, local communities and project institutions, must be encouraged to explore options for the expansion of sandalwood production in the country.

Conclusion

Interest is increasing in the production and trade of PNG sandalwood. Overharvesting of natural stocks, regular fire outbreaks and the growing dependency on a cash economy in local communities, however, are placing a burden on sandalwood protection, regeneration and development. The continued expansion of garden plantings, woodlots, plantations and enrichment plantings is urgently needed to restore PNG’s sandalwood resources. This, along with improved management of the natural resource, will enable and support the long-term supply of sandalwood to meet the high international demand. Collaboration must be strengthened between all stakeholders and awareness and community engagement encouraged if PNG is to achieve the sustainable development of its sandalwood resources.

Clear policies and regulations, such as standalone guidelines for the sale of minor forest products and specific strategies for plantation-grown and natural sandalwood development, management, use and protection, must be developed for sustainable sandalwood production and trade. Harvesting records, management planning and monitoring must be improved to effectively cater for the industry in PNG. There is considerable scope to develop effective policies that support a more regulated, legal and sustainable trade in PNG sandalwood and a more systematic approach to assisting resource owners in establishing new sandalwood plantings. This would help in conserving remaining genetic resources in smallholder woodlots and gardens and enable the development of a new source of future income for those communities. More research and development work is needed to guide the future growth of the sandalwood industry in PNG and the surrounding region.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of ACIAR through previous projects and the current project (FST/2014/069). Special thanks to Michael Poesi (former National Forest Inventory National Coordinator) for his insights into the development and trade of minor forest products in PNG; Paul Macdonell for providing the sandalwood distribution map; Theresa Wari (FDD-PNGFA) for providing valuable information and data on sandalwood export and processing in PNG; and Anne Martin Timi from Mijoan Ltd (Exporter) for her valuable insights into the sandalwood trade in PNG. The study was informed by previous work carried out by the PNGFA, the Foundation for People and Community Development Inc. (FPCD) and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). The authors thank the administrations of Gulf and Central provinces and their respective district and local governments. Lastly, TANIKIU APA’UANA to the local community of Iokea in Gulf Province, Girabu village in Central Province and the Kairuku District communities, especially Babiko, Biotou, Eboa, Ipaipana, Mou, Nikura, Rapa and Vanuamai, for allowing and participating in the research and trial plot establishments.

Disclosure statement

T. Page has a small sandalwood planting of fewer than 100 S. album. No other potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. All views expressed in this article are the authors own and do not represent the opinions of any entity whatsoever with which we have been, are now or will be affiliated.

Notes

1 USD 1 = PGK 3.44.

References

- Baynes J, Herbohn J, Unsworth W. 2017. Reforesting the grasslands of Papua New Guinea: the importance of a family-based approach. Journal of Rural Studies. 56:124–131. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.09.012.

- Bosimbi D. 2005. Sandalwood (Santalum macgregorii) in Papua New Guinea. In: Thomson L, Bulai S, Sovea L, editors. Proceedings of the 3rd Regional Workshop on Sandalwood Research, Development and Extension in the Pacific Islands and Asia; 2002 Oct 7–11; Noumea, New Caledonia. Suva (Fiji): Secretariat of the Pacific Community; p. 95. Available from: http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/12975-7.pdf

- Bosimbi D, Bewang IF. 2007. Report on sandalwood research, development and extension in Papua New Guinea. In: Thomson L, Bulai S, Wilikibau B, editors. Proceedings of the Regional Workshop on Sandalwood Research, Development and Extension in the Pacific Islands and Asia; 2005 Nov 28–Dec 1; Nadi, Fiji. Suva (Fiji): Secretariat of the Pacific Community; p. 57–61, 151–174. doi:10.4324/9781315049731-13.

- Brand J, Norris L, Dumbrell I. 2012. Estimated heartwood weights and oil concentrations within 16-year-old Indian sandalwood (Santalum album) trees planted near Kununurra, Western Australia. Australian Forestry. 75:225–232.

- Braun N, Meier M, Hammerschmidt F. 2005. New Caledonian sandalwood oil – a substitute for east Indian sandalwood oil? Journal of Essential Oil Research. 17:477–480.

- Brophy JJ, Doran JC, Goldsack RJ, Niangu M. 2009. Heartwood oils of Santalum macgregorii F. Muell. (PNG Sandalwood). Journal of Essential Oil Research. doi:10.1080/10412905.2009.9700161.

- Bush D, Brophy J, Bolatolu W, Dutt S, Hamani S, Doran J, Thomson L. 2020. Oil yield and composition of young Santalum yasi in Fiji and Tonga. Australian Forestry. 83(4):238–244.

- Bush D, Thomson LAJ, Bolatolu W, Dutt S, Hamani S, Likiafu H, Mateboto J, Tauraga J, Young E. 2020. Domestication provides the key to conservation of Santalum yasi – a threatened Pacific sandalwood. Australian Forestry. 83(4):186–194.

- Butaud J. 2015. Reinstatement of the Loyalty Islands Sandalwood, Santalum austrocaledonicum var. glabrum (Santalaceae), in New Caledonia. PhytoKeys. 56:111–126.

- ISO. 2002. 3518:2002(E) Oil of sandalwood (Santalum album L.). Geneva (Switzerland): International Organization for Standardization.

- Kiapranis R. 2006. Status of sandalwood conservation in Western Province, Papua New Guinea. In: Thomson L, editor. Regional Workshop on Sandalwood Resource Development, Research and Trade in the Pacific and Asian Region; 2010 Nov 22–25; Port Villa, Vanuatu. Cairns (Australia): James Cook University, Secretariat of the Pacific Community; p. 27–31.

- LCTP (Legislative Council for Territory of Papua). 1909. Timber Ordinance 1909–1920. Territory of Papua. Available from: http://www.paclii.org/pg/legis/papua_annotated/to19091920135/

- Moretta P. 2001. Extraction and variation of the essential oil from Western Australian sandalwood (Santalum spicatum) [PhD thesis]. Perth (Australia): University of Western Australia.

- Page T, Doran J, Tungon J, Tabi M. 2020. Participatory domestication strategy for Santalum austrocaledonicum in Vanuatu. Australian Forestry. 83(4):216–226.

- Page T, Jeffrey G, Macdonell P, Hettiarachichi D, Boyce M, Lata A, Oa L, Rome G. 2020. Morphological and heartwood variation of Santalum macgregorii in Papua New Guinea. Australian Forestry. 83(4):195–207.

- Page T, ll I, Russell M, Leakey R. 2007. Evaluation of heartwood and oil characters in seven populations of Santalum lanceolatum from Cape York. In: Thomson L, Bula S, Wilikibau B, editors. Regional Workshop on Sandalwood Research, Development and Extension in the Pacific Islands and Asia; 2005 Nov 28–Dec 1; Nadi, Fiji. Suva (Fiji): Secretariat of the Pacific Community, Australian Agency for International Development Assistance, German Agency for Technical Cooperation); p. 131–136.

- Page T, Southwell I, Russell M, Tate H, Tungon J, Sam C, Dickinson G, Robson K, Leakey R. 2010. Geographic and phenotypic variation in heartwood and essential oil characters in natural populations of Santalum austrocaledonicum in Vanuatu. Chemistry and Biodiversity. 7:1990–2006.

- Page T, Tate H, Tungon J, Tabi M, Kamasteia P. 2012. Vanuatu sandalwood: growers’ guide for sandalwood production in Vanuatu.

- Paul JH. 1990. The status of sandalwood in Papua New Guinea. In: Hamilton L, Conrad CE, technical coordinators. Proceedings of the Symposium on Sandalwood in the Pacific; 1990 Apr 9–11; Honolulu, Hawaii. Berkeley (CA): Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service. 8(1985):76–78. General Technical Report PSW-GTR-122.

- Rai SN, Sarma CR. 1990. Depleting sandalwood production and rising prices. Indian Forester. 116(5):348–355.

- Subasinghe S, Samarasekara S, Millaniyage K, Hettiarachchi D. 2017. Heartwood assessment of natural Santalum album populations for agroforestry development in Sri Lanka. Agroforestry Systems. 91:1157–1164.

- Thomson LA. 2020. Looking ahead – global sandalwood production and markets in 2040, and implications for Pacific Island producers. Australian Forestry. 83(4):245–254.