ABSTRACT

City road verges often represent existing green space and provide opportunities for ecological enhancement. Urban greenspace improvement initiatives at the residential verge scale require genuine community support and engagement for success. We examined a community-based voluntary assisted verge greening program designed to enhance greenspace connectivity using native plants in a local municipality in Perth, Western Australia. A social survey of verge-greening program participants and non-participants was conducted to understand factors associated with community involvement. Results indicated general resident support for the program, where both groups viewed the program objectives positively. However, non-participants were less convinced, than participants, of the likelihood that the verge greening program would achieve its aims and the merits of some aims. This paper provides insight into a voluntary community engagement tool for developing urban green space connectivity and enhancing natural values at the residential roadside verge level.

Introduction

Urban green space comprises a variety of vegetated areas in the urban environment including remnant vegetation, public parks, private gardens and vegetated streetscapes (Roy, Byrne, and Pickering Citation2012; Rupprecht and Byrne Citation2014; Mensah et al. Citation2016). The widely recognised ecological and social benefits of green space in cities has led to a worldwide social interest alongside the development of extensive scholarship on urban greening that aims to inform decision makers, contribute to community understanding, reduce ecological losses and identify challenges in urban-greening programmes (Fuller et al. Citation2007; Van den Berg et al. Citation2010; Kirkpatrick, Davison, and Daniels Citation2012; Beyer et al. Citation2014; Bratman et al. Citation2015; Henderson Citation2018; Wood et al. Citation2018; Parker and Zingoni de Baro Citation2019; Coffey et al. Citation2020; Cooke Citation2020; Mumaw and Mata Citation2022). Despite the acknowledged importance of urban green space, such areas face the continuing challenge of urban expansion and urban densification (Nisbet, Zelenski, and Murphy Citation2011; Ewing, Catterall, and Tomerini Citation2013; Pietilä et al. Citation2015; Sarkar et al. Citation2015; Farkas et al. Citation2023). Urban densification is used as a mechanism to mitigate urban sprawl while housing a growing human population (Haaland and Konijnendijk van Den Bosch Citation2015). In many cities urban green spaces, particularly remnant vegetation and private gardens, are being reduced, fragmented, or removed (Haaland and Konijnendijk van Den Bosch Citation2015). At the same time, residential road verges comprise a significant part of the global urban landscape (Rupprecht and Byrne Citation2014). Phillips et al. (Citation2020a) state that road verges are ‘strips of land in the immediate vicinity of roads that separate them from the surrounding landscape’. As extensive linear areas traversing urban landscapes, vegetated road verges can function as ecological corridors that enhance green space connectivity and biodiversity values in fragmented urban areas (Douglas and Sadler Citation2011; Arenas et al. Citation2017; O’Sullivan et al. Citation2017; Phillips et al. Citation2020b, Citation2021).

Australian residential urban road verges are part of the public road reserve, located between the edge or kerb of a carriageway and the road reserve boundary (Main Roads Citation2011), In Australian city residential areas, the road verge boundary commonly abuts private residential property (Main Roads Citation2020), Hence the road verge generally occupies the space between the carriageway and private property boundary and may range in width from virtually non-existent to several metres wide (Main Roads Citation2020). Many urban road verges in Australia are common areas of lawn grass (and occasionally trees and weeds) with limited biodiversity (e.g. ).

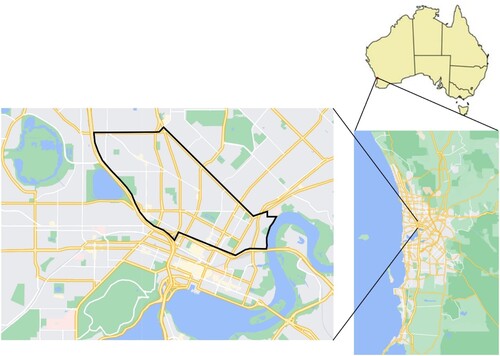

Figure 1. Location of City of Vincent study area within the Perth Metropolitan Area, Western Australia.

Source: adapted from Google maps.

Urban verges that host locally native vegetation can potentially afford several benefits (Hunter and Hunter Citation2008; Goddard, Dougill, and Benton Citation2010; Ewing, Catterall, and Tomerini Citation2013; Standish, Hobbs, and Miller Citation2013; Haaland and Konijnendijk van Den Bosch Citation2015). Native vegetation is suited to the local climate and can provide optimal habitat for native wildlife (Stenhouse Citation2004a; Goddard, Dougill, and Benton Citation2010; Davis and Wilcox Citation2013). In being suited to the local climate native plants, because of their adaptive traits, use less water and are better able to tolerate variation in environmental conditions such as limited water and nutrient resources (Goddard, Dougill, and Benton Citation2010; de Carvalho et al. Citation2022). Accordingly, road verges comprised of native vegetation () contribute to biodiversity and increase available habitat while facilitating connectivity between patches of urban green space (Ramalho et al. Citation2014; Perkl Citation2016; Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017). Given that up to 30% of the green space in a city occurs as road verge, its role in ecological functioning, biodiversity conservation and human well-being is highly significant in enhancing the quality of city living (Marshall, Grose, and Williams Citation2019a; Phillips et al. Citation2020a; Nieuwenhuijsen Citation2021). Moreover, urban greening is becoming increasingly important for mitigating urban heat island effects and in the modulation of stormwater discharge under emerging climate change scenarios (e.g. Chen and You Citation2020; Horne Citation2021; Farkas et al. Citation2023). Given the vital role that vegetation plays in the urban environment, it is important to understand public support for, and the perceived success, of local government initiatives regarding urban greening and especially in relation to residential roadside verge enhancement.

Figure 2. Examples of residential urban road verges of varying width in the City of Vincent with non-adopted verges comprising lawn (a, b) and adopted verges with native plantings (c, d). (Photo source: authors)

Community involvement in residential road verge enhancement

Attitudes and beliefs towards urban-greening programs have been variously explored in Chinese and North American contexts (e.g. Balram and Dragićević Citation2005; Jim and Chen Citation2006; Lo and Jim Citation2012; Shan Citation2012). The urban green space literature from Australia is paying increasing attention to the environmental role, political and social aspects of residential road verges (e.g. Ligtermoet et al. Citation2021; Barona et al. Citation2022; Hunt et al. Citation2022). Further to this, Kirkpatrick, Davison, and Daniels (Citation2012) and Kendal et al. (Citation2022) posit that people are mostly positive about trees in the urban environment. Kendal et al. (Citation2022) additionally providing a useful definition of ‘attitude’ as being ‘people’s positive or negative evaluation of things’, although previously Kirkpatrick, Davison, and Daniels (Citation2012) considered that attitudes may not align with practices consistent with those attitudes. For all that there is an increasing need for social information pertaining to road verges that represent existing green space, and which also provide opportunities for ecological enhancement (Barona et al. Citation2022).

Verge enhancement may be implemented in different ways. For example, it may be a government-driven process (Henderson et al. Citation2001; Newsome Citation2021), a combined government and public partnership (van der Jagt et al. Citation2017; Coffey et al. Citation2020; Cooke Citation2020; Hunt et al. Citation2022) or a community led road verge greening/gardening initiative (Marshall, Grose, and Williams Citation2019a, Citation2019b). Marshall, Grose, and Williams (Citation2019b) emphasise that optimal ecological and social outcomes of verge greening and enhancement programmes will depend upon effective collaboration between road authorities, residents, and local governments. Moreover, it has previously been reported that effective verge enhancement is unlikely to be achieved through governmental intervention alone (Stenhouse Citation2004b; Ewing, Catterall, and Tomerini Citation2013). Governments generally lack the resources for effective urban greening and may depend upon the intervention of local community groups (Stenhouse Citation2004b). Local government may have conflicting priorities which stretches funds even more, and government may rely on having community support to improve the quality and quantity of urban green spaces (Roy Citation2017; van der Jagt et al. Citation2017). Community engagement is important in the planning of urban green spaces as the local community understand how local areas function (e.g. as a park or thoroughfare), and can suggest ways to improve an area for the whole community (Faehnle et al. Citation2014; Marshall, Grose, and Williams Citation2019a, Citation2020). As previously acknowledged, urban-greening programs driven by government generally require community support and engagement to be effective (Coffey et al. Citation2020; Cooke Citation2020).

Research focus: Urban Perth, Western Australia

While road verges in Australia are part of the public road reserve, local government requires residents to maintain their verge in a reasonable condition that does not pose a safety risk (City of Stirling Citation2022a). Urban verges are commonly maintained and used by residents for a range of purposes such as car parking, a play area for children or as an extension of the private garden. Resident community support for any verge planting program is essential as it is the residents who are responsible for ensuring verges are maintained according to specified local government regulations (Ligtermoet et al. Citation2021). Proactive local governments thus require community support regarding their urban-greening programmes (City of Stirling Citation2022b). The research reported in this paper critically examines the social dimensions of a local government led but community-driven urban-greening program focussed on enhancing the ecological and social values of residential road verges. We compared attitudes and perceptions of residents who participated in the program with those who did not, regarding the program and its aims. While this study was conducted in 2017–2018, the findings are relevant owing to the paucity of research regarding community views towards verge-based greening programs and the growing recognition of road verges in terms of their potential contribution to urban greening (Ligtermoet et al. Citation2022). Understanding community perceptions of urban green space connectivity programs offers a valuable learning opportunity for urban/suburban settings globally.

Methods

Study area

The study area was within the City of Vincent, a local government area (municipality) in the Perth Metropolitan Area, the capital of Western Australia (WA) (). Perth is a sprawling city, based on a traditional grid layout, mainly consisting of low density, detached housing and a resident population of approximately 2 million people spread over 6418 km2 (Dushkova et al. Citation2021).

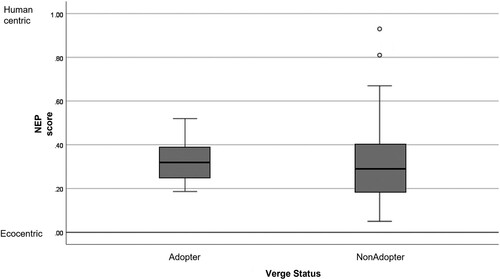

Figure 3. Verge adopter (n = 91) and non-adopter (n = 70) environmental worldview scores calculated using the New Ecological Paradigm Scale.

The Perth Metropolitan Area experiences a Mediterranean climate with hot dry summers (24.8°C annual mean maximum) and cool, wet winters (12.9°C annual mean minimum), with an annual mean rainfall of 850 mm, although rainfall is not uniform across the extensive urban area (BOM Citation2023). The Perth area is also located in one of only two recognised biodiversity hotspots in Australia and 34 worldwide (Dushkova et al. Citation2021; Ritchie et al. Citation2021). The Swan Coastal Plain is recognised for its diverse range of endemic species, with the area originally dominated by extensive wetlands, Banksia woodlands and Tuart Forest both of which are formally recognised as threatened. These endemic native species and ecosystems are now under significant threat due to habitat fragmentation and loss mainly resulting from urban development and associated land clearing. Approximately 25% of the original native vegetation remains as remnant patches of varying sizes across the metropolitan area (Tomlinson, Smit, and Bateman Citation2021) and is under threat from groundwater abstraction, altered fire regimes and disease caused by phytophthora cinnamomi (Shearer and Dillon Citation1996; Groom, Froend, and Mattiske Citation2000; Ritchie et al. Citation2021). About 17% of the Perth area is urban greenspace of varying types, including parklands (Dickinson et al. Citation2018).

The City of Vincent is a municipality situated close to the central business district of Perth. The City has approximately 36,537 residents and 18,159 private dwellings (ABS Citation2021) across a total area of 11.4 km2, with 139 km of road (https://profile.id.com.au/vincent). The City of Vincent resident median weekly household income is AU$2,209, compared to the Australian national median of AU$1,746. A higher proportion of residents are in professional occupations (40%) and have a higher level of educational attainment (46% university degree) compared to the national population (24% and 26%, respectively). A higher proportion of residents have both parents who were born in a country other than Australia (43.3%) compared to 38% of the Australian population (ABS Citation2021). Thus, City of Vincent residents are more likely to have migrant parents, be relatively well educated and have higher incomes compared to the wider Australian population. Furthermore, the City of Vincent includes a range of residential housing types, from suburban areas with detached houses on private properties of several hundred square metres, with road verges of varying sizes, through to inner-city high-density residential areas with little or no road verge. The City of Vincent’s area of public green space, not including road verges, equates in total to about 9.3% of the area of the municipality (https://www.vincent.wa.gov.au/statistics.aspx).

City of Vincent adopt-a-verge program

The City of Vincent implemented an adopt-a-verge program in 2013 as part of a wider municipal urban-greening strategy. The adopt-a-verge program encouraged and facilitated residents to plant native vegetation on the verge area between their property and the road reserve carriageway, usually replacing existing verge lawn and weeds while retaining any existing trees (). The program is promoted on the City of Vincent official website and Facebook as well as being promoted on social media channels by the City of Vincent’s elected representatives. The community-based program had six stated aims:

encourage planting of native vegetation,

increase local biodiversity,

contribute to urban greening,

create wildlife corridors,

enhance local beauty, and

contribute to community wellbeing.

To adopt a verge, residents formally applied to the City as part of a biannual application process. Applications included an indicative plan for the verge design (shape, area, special features such as, paths, boulders or logs). Once the application was accepted, The City removed grass and existing topsoil from the nominated verge, applied a layer of mulch to the verge and provided the residents with up to 20 free native plant tube stock. The resident was responsible for planting and maintenance of their adopted verge. Between 2013 and 2017, resident households in the City of Vincent adopted 332 verges. Aside from this study, there has been no formal evaluation of the adopt a verge program and achievement of its aims since its inception. The lack of evaluation is primarily owing to a lack of staff and resources available for undertaking such as task within the City of Vincent.

Social survey

Social survey sampling approach

The social survey included two sample groups: a questionnaire distributed to households participating in the adopt-a-verge program (adopters); and a questionnaire distributed to households not participating in the adopt-a-verge program (non-adopters). Adopters were identified as those recorded on the City of Vincent’s adopt-a-verge registration database. Non-adopters were those households not recorded on the adopt-a-verge program database. Non-adopter houses, with a road verge area, in the same streets as those included in the adopter sample were targeted to reduce potential confounding factors such as neighbourhood demographic characteristics and non-adopter social norms bias (Germar and Mojzisch Citation2019).

Social survey design

Both adopters and non-adopters completed similar questionnaires with slight variations to accommodate their verge adoption status ().

Table 1. Summary of adopter and non-adopter social survey questionnaire items.

Attitudes towards each of the six stated adopt-a-verge program aims were measured drawing on techniques applied by Brown, Ham, and Hughes (Citation2010) and Hughes, Ham, and Brown (Citation2009). Each of the six aims were rated separately using two seven-point rating scales: a unipolar likelihood rating scale (0–6) regarding the likelihood the program would achieve the respective stated aims, and a bipolar evaluation rating scale (−3 to +3) regarding whether the aims were good or bad things to achieve. This approach provided a more nuanced insight into adopter and non-adopter attitudes towards the program aims relative to a single attitudinal rating scale (Obregon et al. Citation2020). Environmental world view of Adopters and Non-adopters was measured using the New Ecological Paradigm scale (Dunlap et al. Citation2000). The intent was to identify any relationships between environmental worldview and verge adoption behaviour.

The New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale consists of 15 statements regarding the relationship between humans and nature, that are rated on a Likert scale from agree to disagree. The 15 statements are broadly divided into anthropocentric and ecocentric conceptualisations of the human-nature relationship. The NEP has been used to measure environmental attitudes, beliefs and worldviews of the general public as well as identifying differences between specific groups within a community. The scale has demonstrated criterion validity, meaning that the NEP is reliably predictive of environmental values and behaviours (Dunlap et al. Citation2000). Understanding environmental world view provides insights into why particular environmental behaviours are, or are not, carried out by a group of interest (Rossi et al. Citation2015).

General demographic information was collected to characterise the sample and any potential differences between verge adopters and non-adopters.

Social survey distribution

All Adopters on the adopt-a-verge registration database were sent an email, or hard copy letter if email was not available, in June 2017 informing them of the study and advising them that researchers would be knocking on doors and requesting residents to complete a questionnaire about their verge. The door-to-door survey was conducted between September and December 2017. Adopters who were at home were invited to participate and complete a questionnaire. If they agreed, researchers asked participants each question in turn and entered the responses online using a portable device. Where adopters were not able to complete the questionnaire immediately, an identical but hardcopy version of the questionnaire was provided with a reply-paid envelope for later completion and return by the resident. If residents were not home at the time of door knocking, a hardcopy questionnaire, reply-paid envelope and a brief information letter explaining the study were left in the resident’s letterbox.

Non-adopters living in the same streets as the adopters received a hand delivered hardcopy letter inviting them to participate in an online version of the social survey, with a URL and QR code link to the questionnaire. Letters were hand delivered to resident letterboxes in the study area between September and October 2017.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software (IBM SPSS v24). The analysis included descriptive statistics, Chi-square tests of association for categorical data and nonparametric tests (such as Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal Wallis tests) for ordinal data. The New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) Scale statement ratings were totalled for each respondent, with human-centric statements reverse coded to create a total score that was subsequently standardised to a fraction ranging from zero (ecocentric) to one (human centric). Mann–Whitney U tests were used to compare the NEP score between adopters and non-adopter groups. The perceived likelihood and evaluation ratings for each of the six program aims were compared within and between the adopter and non-adopter groups using nonparametric statistical tests. The product of the likelihood and evaluation ratings for each program aim was calculated for each respondent to generate attitude scores ranging from negative 18 (very likely/very bad) to positive 18 (very likely/very good). The attitudes scores for each program aim were compared within and between the adopter and non-adopter groups using nonparametric statistical tests.

Results

Respondent profile

Of the 198 verge adopters invited to participate in the social survey, 91 completed a questionnaire either in person or self-completed and returned in their own time (46% response rate). Out of 3000 letters delivered to non-adopter households, 109 attempted the questionnaire (3.4% response rate). Of the responses received, 71 (65%) were usable. A total of 38 responses were deemed unusable because the questionnaire was mostly incomplete, or the respondents indicated they had adopted, or planned to adopt their verge but were not registered on the City’s database.

A significant relationship was evident between verge status and proportion of home ownership (X2 = 5.542, df = 1, p = 0.020), the number of household occupants (Mann–Whitney U = 3783.5, p = 0.02), and the number of adult children living at home (X2 = 4.742, df = 1, p = 0.030). Verge adopter respondents tended to have a lower proportion of renters, fewer household occupants and fewer adult children living at home, relative to the non-adopter sample.

Comparison of the New Ecological Paradigm scale scores indicated that the environmental worldview of verge adopters (n = 91) and non-adopters (n = 70) was not significantly different (Mann–Whitney U = 2400.5, z = −1.484, p = 0.138) (). Non-adopters had a broader spread of environmental world view scores.

Reasons for adopting or not adopting verge

The most indicated reasons for adopting a verge were: aesthetic appeal (77% of respondents); reducing water use (53% of respondents) and because it is seen as good for the environment (50% of respondents). A small proportion of respondents indicated they participated in the adopt-a-verge program because their family, friends or neighbours were participating ().

Table 2. Reasons indicated by respondents for adopting a verge (n = 91) and not adopting a verge (n = 69).

Commonly indicated reasons for not adopting the verge were a lack of awareness of the program (33% of respondents); needing the verge for other uses (e.g. car parking) (23% of respondents); and/or not having enough time to be involved in the program (22% of respondents). A small proportion of non-adopter respondents were aware but not interested in the program (7.2%) or indicated that they did not like native plants (7.2%). There was no significant statistical relationship between reasons indicated for not adopting the verge, NEP score, or the rating of the program aims.

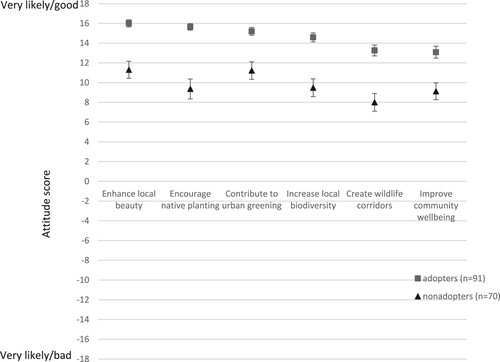

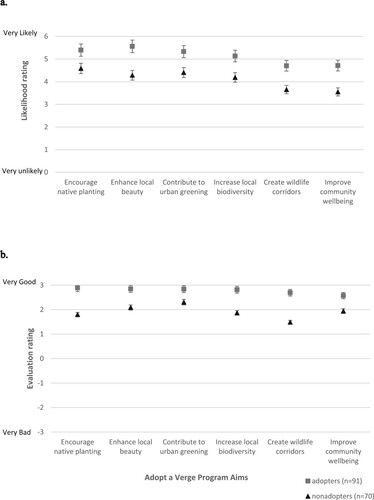

Adopt-a-verge program aims ratings

All adopter likelihood and evaluation ratings of the verge adoption program aims were significantly more positive than the non-adopter ratings (, ). This result indicates adopters considered that the aims were more likely to be achieved when compared with the ratings of non-adopters. Similarly, while both adopters and non-adopters rate all aims as good things to do, non-adopters tended to rate the aims less positively compared to the adopter ratings.

Figure 4. Adopter and non-adopter mean likelihood (a) and evaluation (b) ratings of the adopt-a-verge program aims (error bars = standard error of the mean).

Table 3. Mann–Whitney U test results for pairwise comparisons between adopters (n = 91) and non-adopters (n = 70) regarding adopt-a-verge program aims likelihood and evaluation ratings.

Within group analysis indicated that non-adopters rated the likelihood (X2 = 49.660, df = 5, p ≤ 0.001) and evaluation (X2 = 13.085, df = 5, p < 0.001) of the six respective program aims significantly differently, as did adopters (likelihood X2 = 53.945, df = 5, p < 0.001; evaluation X2 = 25.954, df = 5, p < 0.001). These differences indicate that respondents within each group rated some program aims as less positive or less likely than other aims.

In terms of the likelihood that the program aims would be achieved, adopters rated ‘Enhance local beauty’ and ‘Encourage native planting’ as significantly more likely than the remaining aims (). Non-adopters rated all aims as equally likely, except ‘improve community wellbeing’ and ‘create wildlife corridors’, which were rated significantly less likely to be achieved relative to the other program aims. In terms of the program aims as good things to do, adopters rated ‘create wildlife corridors’ and ‘improve community wellbeing’ less positively than the remaining aims.

Table 4. Adopter pairwise comparisons of adopt-a-verge program aim ratings for likelihood and evaluation (n = 91).

In terms of program aim evaluation, non-adopters rated ‘Create wildlife corridors’ significantly less positively than the remaining aims, except ‘Encourage native planting’ ().

Table 5. Non-adopter pairwise comparisons of adopt-a-verge program aim ratings for likelihood and evaluation (n = 70).

The differences in likelihood and evaluation ratings within and between the adopter and non-adopter groups resulted in differences in the attitudes towards each of the program aims (). The largest difference between the two groups was the attitude (Kendal et al. Citation2022) towards ‘Encouraging native planting’ (Mann–Whitney U = 1791.0, z = −4.883, p < 0.001), where non-adopter attitudes (mean attitude score = 9.36) were significantly less positive compared to the adopter attitudes (mean attitude score = 15.36). The results suggest that the less positive non-adopter attitude towards encouraging native planting is mainly associated with the greater difference, between the adopter and non-adopter groups, in the evaluation rating of this aim (good or bad thing to do). That is, while non-adopters tended to indicate the aim was very likely to be achieved, non-adopters were less positive about whether the aim was a good thing to do.

Discussion

This paper has quantified some key social aspects of a community led, local municipality facilitated voluntary urban-greening program, known as adopt-a-verge. Results revealed program participants (adopters) and non-participants (non-adopters) were similar in their environmental world view, based on the NEP, and both viewed the adopt-a-verge program in a positive light in terms of its aims and the likelihood those aims would be achieved. However, program adopters were significantly more positive than non-adopters in terms of the likelihood the aims could be achieved and how ‘good’ they were. This formed the foundation for a more positive attitude towards the program aims by the adopters. Adopter reasons for participation mainly included aesthetic appeal while reduced water use and environmental benefits were indicated to a lesser extent. Non-adopter reasons for not participating in the program were mostly associated with a lack of awareness of the program and verges being required for other uses not compatible with verge plantings. Adopters tended to have fewer people living in their household and less older children, than the non-adopters. These results provide insights into the facilitators and perceived barriers to community involvement in an urban-greening initiative.

While community support is vital for successful local urban-greening initiatives (Roy Citation2017; van der Jagt et al. Citation2017), understanding why community members may or may not participate enables program managers to adjust or focus the program to maximise involvement. At the same time, various authors emphasise that much remains to be done in relation to understanding community values and beliefs when it comes to various urban-greening programmes (Barona et al. Citation2022; Kendal et al. Citation2022). The results of this study suggest that environmental world view was not a significant factor determining involvement in the program. Both adopter and non-adopter groups had similar worldviews, generally tending towards the ecocentric end of the spectrum. Moreover, effectively encouraging environmentally responsible behaviour, such as planting native vegetation on the residential verge, may be best approached through targeting the significant differences between participants and non-participants associated with performing the behaviour (Hughes, Ham, and Brown Citation2009; Hughes, Weiler, and Curtis Citation2012; Obregon et al. Citation2020). The lack of difference in environmental world view could mean that attempting to encourage greater involvement in planting native vegetation on verges in urban areas by emphasising the general environmental imperative may not be effective. However, Ligtermoet et al. (Citation2021) have proposed that the provision of incentives, education and evidence of benefits has the potential to foster increasing public interest in such programmes. Hunt et al. (Citation2022) have explored public motivations for verge gardens comprising native vegetation in the City of Bayswater LGA in Perth. In this case environmental imperatives such as wildlife corridors, reducing urban heat, re-wildling, water conservation and aesthetics were identified as motivating factors with those people that had a verge garden comprising native vegetation.

While about half of adopter respondents in the City of Vincent (this study) indicated environmental reasons for participation, the vast majority indicated aesthetic appeal of native plantings on their verge as the reason for participation. This suggests that the environmental imperative, while present, is not a primary reason for involvement in the program. Non-adopters stated several main reasons for not being involved including not being aware of the program, as well as requiring the verge for other purposes (such as car parking). It seems that environmental concerns in relation to promoting urban greenspace were not a top-of-mind factor regarding involvement in the adopt-a-verge program. Rather, practical considerations regarding established views on verge value and function (Muratet et al. Citation2015; Marshall, Grose, and Williams Citation2019a) and the extent of awareness of the program appeared to dominate. While identifying enabling factors, such as evidence-based approaches, for verge-greening programmes Ligtermoet et al. (Citation2021) also specified that stakeholders were interested in a variety of preferences (natives, exotics, car parking) some which may act as barriers to participation.

In the City of Vincent, the six stated aims of the adopt-a-verge program relate to enhancing connectivity of urban green space, to enhance biodiversity and provide some key social benefits at the local municipal scale. The benefits and challenges of establishing wildlife corridors, including the use of road verges, to connect fragmented urban greenspace are well recognised (Arenas et al. Citation2017; Phillips et al. Citation2020b, Citation2021). While both adopters and non-adopters were positive about the program aims, non-adopters had a significantly less positive attitude compared to the adopter respondents. This less positive attitude was composed of non-adopter beliefs that some program aims were less likely to be achieved, while also being less positive about the aims as good things to do, relative to adopter beliefs. For example, while non-adopters and adopters both rated the aim, ‘encourage native planting’ as likely to be achieved, non-adopters were less positive about this aim as being achievable and considerably less positive about this aim as a good thing to do. Community support for urban-greening programs requires understanding and support of the program aims (Marshall, Grose, and Williams Citation2020). Encouraging the involvement of non-adopters in the program may not only require raising effective public awareness about the program but may also require different messaging emphasising the achievability and merit of the specific program aims (Ligtermoet et al. Citation2021; Hunt et al. Citation2022).

The mainly aesthetic reasons for adopting a verge indicated by adopters aligns with the adopters’ significantly higher likelihood and evaluation rating of ‘Enhance local beauty’ compared to the other program aims (c.f. Muratet et al. Citation2015; Marshall, Grose, and Williams Citation2019a). Coupled with this, adopters rated the ‘create corridors’ aim lower than the other aims. This suggests that the connectivity and biodiversity aspects, as central components of the program from an urban greening and biodiversity perspective, are generally less important to the respondents than the aesthetic appeal of planting native vegetation on their road verges. This has ramifications for community engagement in urban-greening programs such as adopt-a-verge. Considerations that warrant inclusion and topics of further research include elements of social geography such as demographic profiles including component immigrant populations and trends towards gentrification. Spatial geographic aspects worthy of consideration are housing density and proximity to existing green space. Place attachment and environmental values are significantly influenced by the before mentioned considerations. For example, Hunt et al. (Citation2022) suggest that households located next to existing green space are more likely to be interested in nature which in turn is likely to lead to greater native garden densities. Hunt et al. (Citation2022) also reported that the southern area of the City of Bayswater in Perth, which had a higher density of verge gardens, was also typified by retirees, smaller household sizes and higher than average incomes. Further to understanding public opinion would be appreciation of the role of networks such as local government authorities, advocacy groups and environmental consultants (Ligtermoet et al. Citation2021). This is especially so regarding their role in community engagement such as in providing incentives and educational opportunities in support of urban-greening initiatives.

Conclusion

The on-going geographical research on urban greening ranges from climate science, urban forestry, ecology, remote sensing, various applications of geographic information systems such as spatial analysis, as well as the broad area of human geography. From the human geographical perspective urban green space research also includes sustainability science, political analysis, psychology, demography, town planning and the framing of policy. This paper contributes additional knowledge in the Australian human geographical context by providing some insights into the social dimensions of a community-based urban-greening program aimed at increasing urban green space connectivity by facilitating residents to plant locally native vegetation on residential road verges. The findings highlight differences between adopters (program participants) and non-adopters (those not participating) in terms of their reasons, beliefs and attitudes towards the program aims. Adopters were primarily focussed on the aesthetic value they associate with planting native vegetation on their road verge. Non-adopters tended to indicate they were not aware of the program or required the verge for other uses not compatible with planting native vegetation. Non-adopters tended to have fewer positive attitudes than adopters towards the program aims, particularly planting native vegetation, mainly determined by less positive beliefs about that being a good thing to do.

Community engagement and support is vital for effective implementation of urban-greening programs. Understanding the reasons, beliefs and attitudes relating to engagement or lack of engagement can help to inform managers about how to better engage with local communities to ensure the effectiveness of urban-greening initiatives such as the adopt-a-verge program. In the context of this study, emphasising the importance of creating corridors to enhance greenspace connectivity (a central aim of the program) is less likely to encourage involvement compared with promoting the aesthetic and practical attributes of planting native vegetation. This paper thus provides some further understanding into the socio-political context regarding resident’s perceptions of the role and importance of residential roadside verges in the broader picture of urban greening. In recent years the geographical scope of urban green space studies has changed from being focused on China and the USA. Australian studies are now more prominent and provide important perspectives on the fostering and management of urban green space in rapidly warming and drying Mediterranean type climates. In acknowledging that urban sprawl often includes a vast network of residential verges then community support is vital in the push to convert to native vegetation and in the promotion of native habitat. The lesson learnt from this study is that community support is not necessarily associated with pro-environmental attitudes, and this has implications for policy development and the application of educational strategies. Perth is a sprawling city that is adopting densification resulting in a reduction of greenspace. Understanding the role of residential road verges in planning for urban green space thus remains an important topic of research.

Acknowledgements

Joe Fontaine with project supervision and assistance in the field.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arenas, J. M., A. Escudero, I. Mola, and M. A. Casado. 2017. “Roadsides: An Opportunity for Biodiversity Conservation.” Applied Vegetation Science 20 (4): 527–537. doi:10.1111/avsc.12328.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2021. “Vincent. 2021 Census all persons QuickStats.” https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/LGA58570.

- Balram, S., and S. Dragićević. 2005. “Attitudes Toward Urban Green Spaces: Integrating Questionnaire Survey and Collaborative GIS Techniques to Improve Attitude Measurements.” Landscape and Urban Planning 71 (2-4): 147–162. doi:10.1016/S0169-2046(04)00052-0.

- Barona, C. O., K. Wolf, J. M. Kowalski, D. Kendal, J. A. Byrne, and T. M. Conway. 2022. “Diversity in Public Perceptions of Urban Forests and Urban Trees: A Critical Review.” Landscape and Urban Planning 226: 104466. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104466.

- Beyer, K. M., A. Kaltenbach, A. Szabo, S. Bogar, F. J. Nieto, and K. M. Malecki. 2014. “Exposure to Neighborhood Green Space and Mental Health: Evidence from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11 (3): 3453–3472. doi:10.3390/ijerph110303453.

- BOM. 2023. “Climate Statistics for Australian Locations.” http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_009225.shtml.

- Bratman, G. N., G. C. Daily, B. J. Levy, and J. J. Gross. 2015. “The Benefits of Nature Experience: Improved Affect and Cognition.” Landscape and Urban Planning 138: 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.02.005.

- Brown, T., S. Ham, and M. Hughes. 2010. “Picking up Litter: An Application of Theory Based Communication to Influence Tourist Behaviour in Protected Areas.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 18 (7): 879–900.

- Chen, R., and X. Y. You. 2020. “Reduction of Urban Heat Island and Associated Greenhouse gas Emissions.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 25: 689–711. doi:10.1007/s11027-019-09886-1.

- City of Stirling. 2022a. “Verges.” Accessed March 9, 2022. https://www.stirling.wa.gov.au/waste-and-environment/natural-environment-and-conservation/pests-and-weeds.

- City of Stirling. 2022b. “Draft Public Open Space Strategy.” Accessed March 9, 2022https://www.stirling.wa.gov.au/your-city/news/2022/february/draft-public-open-space-strategy.

- Coffey, B., J. Bush, L. Mumaw, L. De Kleyn, C. Furlong, and R. Cretney. 2020. “Towards Good Governance of Urban Greening: Insights from Four Initiatives in Melbourne, Australia.” Australian Geographer 51 (2): 189–204. doi:10.1080/00049182.2019.1708552.

- Cooke, B. 2020. “The Politics of Urban Greening: An Introduction.” Australian Geographer 51 (2): 137–153. doi:10.1080/00049182.2020.1781323.

- Davis, R. A., and J. A. Wilcox. 2013. “Adapting to Suburbia: Bird Ecology on an Urban-Bushland Interface in Perth, Western Australia.” Pacific Conservation Biology 19 (2): 110–120. doi:10.1071/PC130110.

- de Carvalho, C. A., M. Raposo, C. Pinto-Gomes, and R. Matos. 2022. “Native or Exotic: A Bibliographical Review of the Debate on Ecological Science Methodologies: Valuable Lessons for Urban Green Space Design.” Land 11 (8): 1201. doi:10.3390/land11081201.

- Dickinson, D. C., R. J. Hobbs, L. E. Valentine, and C. E. Ramalho. 2018. “Urban Green Space Preference in Perth, Western Australia, and the Significance of ‘Natural’ Green Spaces.” PhD Thesis, Chapter 6. Greenspace Perth: A Social-Ecological Study of Urban Green Space in Perth Western Australia, 147−180.

- Douglas, I., and J. P. Sadler. 2011. “Urban Wildlife Corridors: Conduits for Movement or Linear Habitat?” In The Routledge Handbook of Urban Ecology, edited by I. Douglas, D. Goode, and M. Houck, 298–312. Florence, USA: Taylor and Francis.

- Dunlap, R. E., K. D. Van Liere, A. G. Mertig, and R. E. Jones. 2000. “New Trends in Measuring Environmental Attitudes: Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale.” Journal of Social Issues 56 (3): 425–442. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00176.

- Dushkova, D., M. Ignatieva, M. Hughes, A. Konstantinova, V. Vasenev, and E. Dovletyarova. 2021. “Human Dimensions of Urban Blue and Green Infrastructure During a Pandemic. Case Study of Moscow (Russia) and Perth (Australia).” Sustainability 13 (8): 4148. doi:10.3390/su13084148.

- Ewing, C. P., C. P. Catterall, and D. M. Tomerini. 2013. “Outcomes from Engaging Urban Community Groups in Publicly Funded Vegetation Restoration.” Ecological Management & Restoration 14 (3): 194–201. doi:10.1111/emr.12054.

- Faehnle, M., P. Bäcklund, L. Tyrväinen, J. Niemelä, and V. Yli-Pelkonen. 2014. “How can Residents’ Experiences Inform Planning of Urban Green Infrastructure? Case Study Finland.” Landscape and Urban Planning 130: 171–183. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.07.012.

- Farkas, J. Z., E. Hoyk, M. B. de Morais, and G. Csomós. 2023. “A Systematic Review of Urban Green Space Research Over the Last 30 Years: A Bibliometric Analysis.” Heliyon. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13406.

- Fuller, R. A., K. N. Irvine, P. Devine-Wright, P. H. Warren, and K. J. Gaston. 2007. “Psychological Benefits of Greenspace Increase with Biodiversity.” Biology Letters 3 (4): 390–394. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0149.

- Germar, M., and A. Mojzisch. 2019. “Learning of Social Norms Can Lead to a Persistent Perceptual Bias: A Diffusion Model Approach.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 84: 103801. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2019.03.012.

- Goddard, M. A., A. J. Dougill, and T. G. Benton. 2010. “Scaling Up from Gardens: Biodiversity Conservation in Urban Environments.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25 (2): 90–98. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.07.016.

- Groom, B. P. K., R. H. Froend, and E. M. Mattiske. 2000. “Impact of Groundwater Abstraction on a Banksia Woodland, Swan Coastal Plain, Western Australia.” Ecological Management and Restoration 1 (2): 117–124. doi:10.1046/j.1442-8903.2000.00033.x.

- Haaland, C., and C. K. Konijnendijk van Den Bosch. 2015. “Challenges and Strategies for Urban Green-Space Planning in Cities Undergoing Densification: A Review.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 14 (4): 760–771. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2015.07.009.

- Henderson, S. R. 2018. “Advocating Within and Outside the Shadow of Hierarchy: Local Government Responses to Melbourne’s Outer Suburban Deficits.” Local Government Studies 44 (5): 649–669. doi:10.1080/03003930.2018.1481397.

- Henderson, J. C., A. Koh, S. Soh, and M. Y. Sallim. 2001. “Urban Environments and Nature-Based Attractions: Green Tourism in Singapore.” Tourism Recreation Research 26 (3): 71–78. doi:10.1080/02508281.2001.11081201.

- Horne, J. 2021. “Managing Impacts of Extreme Hydrological Events on Urban Water Services: The Australian Experience.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 37 (6): 907–928. doi:10.1080/07900627.2020.1808447.

- Hughes, M., S. Ham, and T. Brown. 2009. “Influencing Park Visitor Behaviour, a Belief-Based Approach.” Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 27 (4): 38–53.

- Hughes, M., B. Weiler, and J. Curtis. 2012. “What’s the Problem? River Management, Education and Public Beliefs.” Ambio 41 (7): 709–719. doi:10.1007/s13280-012-0282-5.

- Hunt, S., J. Maher, M. S. H. Swapan, and A. Zaman. 2022. “Street Verge in Transition: A Study of Community Drivers and Local Policy Setting for Urban Greening in Perth, Western Australia.” Urban Science 6 (1): 15. doi:10.3390/urbansci6010015.

- Hunter, M. R., and M. D. Hunter. 2008. “Designing for Conservation of Insects in the Built Environment.” Insect Conservation and Diversity 1 (4): 189–196. doi:10.1111/j.1752-4598.2008.00024.x.

- Jim, C. Y., and W. Y. Chen. 2006. “Perception and Attitude of Residents Toward Urban Green Spaces in Guangzhou (China).” Environmental Management 38 (3): 338–349. doi:10.1007/s00267-005-0166-6.

- Kendal, D., C. Ordóñez, M. Davern, R. A. Fuller, D. F. Hochuli, van der Ree Rodney, Livesley Stephen J., and C. G. Threlfall. 2022. “Public Satisfaction with Urban Trees and Their Management in Australia: The Roles of Values, Beliefs, Knowledge, and Trust.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 73: 127623. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127623.

- Kirkpatrick, J. B., A. Davison, and G. D. Daniels. 2012. “Resident Attitudes Towards Trees Influence the Planting and Removal of Different Types of Trees in Eastern Australian Cities.” Landscape and Urban Planning 107 (2): 147–158. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.05.015.

- Ligtermoet, E., C. E. Ramalho, J. Foellmer, and N. Pauli. 2022. “Greening Urban Road Verges Highlights Diverse Views of Multiple Stakeholders on Ecosystem Service Provision, Challenges and Preferred Form.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 74: 127625. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127625.

- Ligtermoet, E., C. E. Ramalho, K. Martinus, L. Chalmer, and N. Pauli. 2021. “Stakeholder Perspectives on the Role of the Street Verge in Delivering Ecosystem Services: A Study from the Perth Metropolitan Region.” Report for the Clean Air and Urban Landscapes (CAUL) Hub, Melbourne, Australia.

- Lo, A. Y., and C. Y. Jim. 2012. “Citizen Attitude and Expectation Towards Greenspace Provision in Compact Urban Milieu.” Land Use Policy 29 (3): 577–586. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.09.011.

- Main Roads. 2011. “Glossary of Technical Terms.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.mainroads.wa.gov.au/technical-commercial/technical-library/road-traffic-engineering/glossary-of-technical-terms/.

- Main Roads. 2020. “Driveways.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.mainroads.wa.gov.au/technical-commercial/technical-library/road-traffic-engineering/guide-to-road-design/additional-road-design2/driveways/.

- Marshall, A. J., M. J. Grose, and N. S. Williams. 2019a. “Footpaths, Tree cut-Outs and Social Contagion Drive Citizen Greening in the Road Verge.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 44: 126427. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126427.

- Marshall, A. J., M. J. Grose, and N. S. Williams. 2019b. “From Little Things: More Than a Third of Public Green Space is Road Verge.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 44: 126423. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126423.

- Marshall, A. J., M. J. Grose, and N. S. Williams. 2020. “Of Mowers and Growers: Perceived Social Norms Strongly Influence Verge Gardening, a Distinctive Civic Greening Practice.” Landscape and Urban Planning 198: 103795. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103795.

- Mensah, C. A., L. Andres, U. Perera, and A. Roji. 2016. “Enhancing Quality of Life Through the Lens of Green Spaces: A Systematic Review Approach.” International Journal of Wellbeing 6 (1): 142–163. doi:10.5502/ijw.v6i1.445.

- Mumaw, L., and S. Bekessy. 2017. “Wildlife Gardening for Collaborative Public–Private Biodiversity Conservation.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 24 (3): 242–260. doi:10.1080/14486563.2017.1309695.

- Mumaw, L., and L. Mata. 2022. “Wildlife Gardening: An Urban Nexus of Social and Ecological Relationships.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 20 (6): 379–385. doi:10.1002/fee.2484.

- Muratet, A., P. Pellegrini, A. B. Dufour, T. Arrif, and F. Chiron. 2015. “Perception and Knowledge of Plant Diversity among Urban Park Users.” Landscape and Urban Planning 137: 95–106. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.01.003.

- Newsome, D. 2021. “Sustainability Can Start with a Garden!.” International Journal of Tourism Cities 7 (4): 887–894. doi:10.1108/IJTC-04-2020-0084.

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. 2021. “New Urban Models for More Sustainable, Liveable and Healthier Cities Post covid19; Reducing air Pollution, Noise and Heat Island Effects and Increasing Green Space and Physical Activity.” Environment International 157: 106850. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2021.106850.

- Nisbet, E. K., J. M. Zelenski, and S. A. Murphy. 2011. “Happiness is in Our Nature: Exploring Nature Relatedness as a Contributor to Subjective Well-Being.” Journal of Happiness Studies 12 (2): 303–322. doi:10.1007/s10902-010-9197-7.

- Obregon, C., M. Hughes, N. Loneragan, S. Poulton, and J. Tweedley. 2020. “A Two-Phase Approach to Elicit and Measure Beliefs on Management Strategies: Fishers Supportive and Aware of Trade-Offs Associated with Stock Enhancement.” Ambio 49 (2): 640–649. doi:10.1007/s13280-019-01212-y.

- O’Sullivan, O. S., A. R. Holt, P. H. Warren, and K. L. Evans. 2017. “Optimising UK Urban Road Verge Contributions to Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services with Cost-Effective Management.” Journal of Environmental Management 191: 162–171. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.12.062.

- Parker, J., and M. E. Zingoni de Baro. 2019. “Green Infrastructure in the Urban Environment: A Systematic Quantitative Review.” Sustainability 11 (11). doi:10.3390/su11113182.

- Perkl, R. M. 2016. “Geodesigning Landscape Linkages: Coupling GIS with Wildlife Corridor Design in Conservation Planning.” Landscape and Urban Planning 156: 44–58. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.05.016.

- Phillips, B. B., J. M. Bullock, J. L. Osborne, and K. J. Gaston. 2020a. “Ecosystem Service Provision by Road Verges.” Journal of Applied Ecology 57 (3): 488–501. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13556.

- Phillips, B. B., A. Navaratnam, J. Hooper, J. M. Bullock, J. L. Osborne, and K. J. Gaston. 2021. “Road Verge Extent and Habitat Composition Across Great Britain.” Landscape and Urban Planning 214. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104159.

- Phillips, B. B., C. Wallace, B. R. Roberts, A. T. Whitehouse, K. J. Gaston, J. M. Bullock, Lynn V. Dicks, and J. L. Osborne. 2020b. “Enhancing Road Verges to aid Pollinator Conservation: A Review.” Biological Conservation 250. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108687.

- Pietilä, M., M. Neuvonen, K. Borodulin, K. Korpela, T. Sievänen, and L. Tyrväinen. 2015. “Relationships Between Exposure to Urban Green Spaces, Physical Activity and Self-Rated Health.” Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 10: 44–54. doi:10.1016/j.jort.2015.06.006.

- Ramalho, C. E., E. Laliberté, P. Poot, and R. J. Hobbs. 2014. “Complex Effects of Fragmentation on Remnant Woodland Plant Communities of a Rapidly Urbanizing Biodiversity Hotspot.” Ecology 95 (9): 2466–2478. doi:10.1890/13-1239.1.

- Ritchie, A. L., L. N. Svejcar, B. M. Ayre, J. Bolleter, A. Brace, M. D. Craig, Belinda Davis, et al. 2021. “Corrigendum to: A Threatened Ecological Community: Research Advances and Priorities for Banksia Woodlands.” Australian Journal of Botany 69 (2): 111–111. doi:10.1071/BT20089_CO.

- Rossi, S. D., J. A. Byrne, C. M. Pickering, and J. Reser. 2015. “‘Seeing Red’ in National Parks: How Visitors’ Values Affect Perceptions and Park Experiences.” Geoforum 66: 41–52.

- Roy, S. 2017. “Anomalies in Australian Municipal Tree Managers’ Street-Tree Planting and Species Selection Principles.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 24: 125–133. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2017.03.008.

- Roy, S., J. Byrne, and C. Pickering. 2012. “A Systematic Quantitative Review of Urban Tree Benefits, Costs, and Assessment Methods Across Cities in Different Climatic Zones.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 11: 351–363. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2012.06.006.

- Rupprecht, C. D., and J. A. Byrne. 2014. “Informal Urban Green-Space: Comparison of Quantity and Characteristics in Brisbane, Australia and Sapporo, Japan.” PloS one 9 (6): e99784. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099784.

- Sarkar, C., C. Webster, M. Pryor, D. Tang, S. Melbourne, X. Zhang, and L. Jianzheng. 2015. “Exploring Associations Between Urban Green, Street Design and Walking: Results from the Greater London Boroughs.” Landscape and Urban Planning 143: 112–125. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.06.013.

- Shan, X. Z. 2012. “Attitude and Willingness Toward Participation in Decision-Making of Urban Green Spaces in China.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 11 (1): 211–217. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2011.11.004.

- Shearer, B. L., and M. Dillon. 1996. “Impact and Disease Centre Characteristics of Phytophthora cinnamomi Infestations of Banksia Woodlands on the Swan Coastal Plain, Western Australia.” Australian Journal of Botany 44 (1): 79–90. doi:10.1071/BT9960079.

- Standish, R. J., R. J. Hobbs, and J. R. Miller. 2013. “Improving City Life: Options for Ecological Restoration in Urban Landscapes and how These Might Influence Interactions Between People and Nature.” Landscape Ecology 28 (6): 1213–1221. doi:10.1007/s10980-012-9752-1.

- Stenhouse, R. N. 2004a. “Fragmentation and Internal Disturbance of Native Vegetation Reserves in the Perth Metropolitan Area, Western Australia.” Landscape and Urban Planning 68 (4): 389–401. doi:10.1016/S0169-2046(03)00151-8.

- Stenhouse, R. N. 2004b. “Local Government Conservation and Management of Native Vegetation in Urban Australia.” Environmental Management 34 (2): 209–222. doi:10.1007/s00267-004-0231-6.

- Tomlinson, S., A. Smit, and P. W. Bateman. 2021. “The Ecology of a Translocated Population of a Medium-Sized Marsupial in an Urban Vegetation Remnant.” Pacific Conservation Biology 28 (2): 184–191. doi:10.1071/PC21005.

- Van den Berg, A. E., J. Maas, R. A. Verheij, and P. P. Groenewegen. 2010. “Green Space as a Buffer Between Stressful Life Events and Health.” Social Science & Medicine 70 (8): 1203–1210. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.002.

- van der Jagt, A. P., B. H. Elands, B. Ambrose-Oji, M. S. Møller, and M. Buizer. 2017. “Participatory Governance of Urban Green Spaces: Trends and Practices in the EU.” Nordic Journal of Architectural Research 3: 11–34.

- Wood, E., A. Harsant, M. Dallimer, A. Cronin de Chavez, R. R. McEachan, and C. Hassall. 2018. “Not all Green Space is Created Equal: Biodiversity Predicts Psychological Restorative Benefits from Urban Green Space.” Frontiers in Psychology 9. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02320.