ABSTRACT

The importance of wetlands as places worthy of protection has been recognised since at least 1975, with the passage of the global wetland treaty, the Ramsar Convention (officially the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat). However, over the past 50 years wetlands have declined and at least 35% of natural wetlands have been lost with more at risk of extinction. Unfortunately, wetland habitats continue to suffer, despite the existence of protection regimes. In this context, this paper invites us to push the way we think about current wetland regulation and protection. Contemporary conceptions of wetlands that underpin dominant protection and management regimes tend to characterise wetlands in a way that overlooks all essential elements of the ecosystem. Our concern is to illuminate the plight of wetland ecosystems as interconnected waterscapes requiring more than a selective or partial regulative protection effort. We argue for a ‘rights of wetlands’ framing for a more holistic approach to regulate the management of these key ecosystems. We situate our argument using a Ramsar-listed wetland example, the Towra Point Nature Reserve, located in Botany Bay (Kamay), Sydney, Australia. Ultimately, we invite a recalibration of regulatory efforts for wetland conservation.

Highlights

Wetlands are amongst the most degraded global ecosystems so the need to rethink their protection regimes is now.

Institutionalising regulatory protection for the entire wetland community might be achieved with a re-boot of pre-existing management approaches.

A management recalibration using a novel ‘Rights of Wetlands’ framing can enable a re-prioritisation of wetlands as important hybrid waterscapes.

Introduction

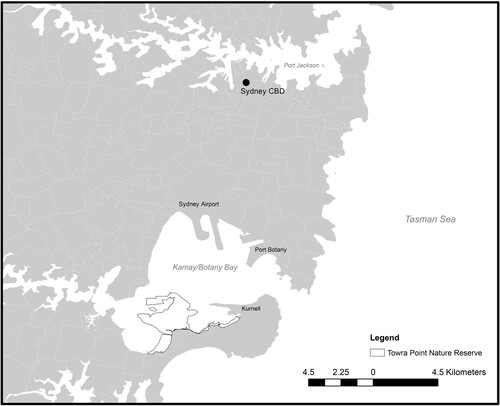

This paper reflects on how the component parts of wetland ecosystems are often treated inequitably through the protection regimes emplaced upon these dynamic places. Our perspective is informed by our field observations of a coastal urban wetland (the Ramsar-listed Towra Point Nature Reserve, Sydney, Australia, .) and by critically reflecting on how it is regulated and protected. We aim to change perspectives in wetland management. We argue there is a need to protect watery, dynamic wetlands as an interstitial space; as a habitat that is always changing and, in the coastal setting of our case study, is neither solely land nor sea and is a place that requires nuanced management attention. Accordingly, we call to reframe wetland protection regimes in terms of rights of nature narrative (Schmidt Citation2022), which sets out a ‘rights of wetlands’ agenda. Before we turn to consider the rights of wetlands for reinvigorating wetlands regulation, together with an exploration of our case study site, we overview the legal geography, ‘shadow’ waters and ‘rights’ framings we use in this paper.

Figure 1. Towra Point Nature Reserve Ramsar-listed Wetland Study Site Location. Map shows suburb boundaries. Ramsar boundary from Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. State suburb boundaries Administrative Boundaries © Geoscape Australia licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0).

A legal geography perspective

Wetland management is not as contingent, and fluid, as might be expected for the protection of these ever-changing material waterscapes. This is largely because flexible regulatory regimes are difficult to both enact and operationalise. As Choi (Citation2022) points out, it is difficult it is to situate watery places into mainstream environmental knowledge systems. Tidal flats are in-between land/water places that give them a slipperiness that characterises and pervades this land-water interface and which, ultimately, undermines their future survival. Choi draws on Lahiri-Dutt (Citation2014) to argue that we need to embrace ‘slippery ontologies’ better suited to wetland’s place-based context in order to defend tidal areas from degradation. This takes place through the idea that locational dynamics are essential to protecting dynamic wetland places. While Choi identifies locational and political-economical elements for critique, we suggest another element needing attention is the regulatory settings placed upon these fluid landscapes. We draw out this element from a legal geography reading of wetland places using a case study of the internationally recognised and Ramsar-listed Towra Point Nature Reserve, Sydney, New South Wales (see ).

We identify and situate ourselves within a legal geography tradition in exposing law’s hidden environmental dimensions (see Carr Citation2023; Carr and Milstein Citation2021), but in this paper, an extensive exposé of legal geography scholarship is beyond our scope (for a focus on key contributions from contemporary Australian legal geography scholarship see Bartel Citation2018; Bartel and Graham Citation2023; Gillespie and O’Donnell Citation2023; Gillespie, Robinson, and O’Donnell Citation2024; O’Donnell, Robinson, and Gilespie Citation2020). The work of Braverman (Citation2015) influences our research, to the extent that we argue for an appreciation of the role of law, but also of the need to consider ‘what’ ‘belongs’ and ‘where’ in biodiversity conservation. Braverman’s work (Citation2015), in unpacking in-situ and ex-situ conservation efforts, and the conundrums associated with these approaches, underpins much legal geography research and sits at the geography and conservation nexus where we situate our work. Considering the systemic loss and degradation of wetlands across the world, despite long-standing legal protections through instruments such as the global wetlands conservation regime of the Ramsar Convention, a critical reconceptualisation of wetlands protection is clearly necessary. In the sections below we argue that such a critical reconceptualisation can be guided by engaging with an emergent ‘rights of nature’ framework.

Wetland protection: selective and exclusionary?

Selective or partial protection regimes are the basic building blocks of Ramsar wetland protections, as the original justification for the Convention was primarily to secure the future of waterbird populations, rather than wetland habitat per se (Ramsar Citation1975). We argue a selective approach to protection continues in contemporary wetland regulatory regimes and that this is increasingly problematic (see also O’Gorman Citation2021, on ‘bird centrism’ below). A focus only on waterbirds or iconic species creates an exclusionary environmental protection practice that can have adverse consequences for an ecosystem that is intrinsically connected to its surroundings, as wetlands are. In the context of the growing need for a whole-of-wetlands approach, we argue that an ecosystem rather than species conservation approach is needed, and similar arguments have been made by O’Donnell (Citation2020) in research about rivers.

Protecting places through individual species is problematic. By way of comparison, in cognate urban places Carver and Gardner (Citation2022) point out,

… reliance on endangered species regulations result in a brittle conservation situation in which a hegemonic species with particular affective affinities and cultural importance to humans is being protected in favor of other, perhaps more threatened species, and in which a particular type of landscape is being preserved in favor of one which might support more species or more effectively counteract climate change. (Carver and Gardner Citation2022, 2307).

We link our advocacy for an ecosystem approach to wetland management (through a ‘Rights of Wetlands’ set out below), to observations about the neglect of undesirable or ‘crappy’ land and waterscapes (Urban Citation2018). Oftentimes, perceived ‘less-than-desirable’ ‘shadow’ places (Plumwood Citation2008; Potter et al. Citation2022) do not enjoy the same supported protection regimes as more ‘beautiful’ places (Gillespie Citation2020). Some urban wetlands, including our case study site (below), might be conceived of in terms of shadow waterscapes (or ‘shadow waters’ following McLean et al. Citation2018). As McLean et al. (Citation2018, 615) write ‘(s)hadow waters are … historically created as particular power structures and narratives (and) are reinforced and ‘normalised’ over time.’ Their use of the word shadow is not necessarily discriminatory or disparaging but is contingent on the situation and interpretation in place and across time (ibid, 616). In a similar vein, here we provide a snapshot of a ‘shadow waterscape’ where the place is valued – differently by various actors – and which we suggest can be read through the regulatory setting (hence our call to adopt a legal geography approach to the analysis of the material world, following Gillespie, Hamilton, and Penny Citation2023; Gillespie, Robinson, and O’Donnell Citation2024). We are inspired by the thinking evident in O’Gorman’s (Citation2021) narration of a series of more-than-human encounters in different Australian waterscapes settings. Our focus on Ramsar wetlands, as a global protected area phenomenon, builds on our previous work (e.g. Della Bosca and Gillespie Citation2020; Gillespie Citation2018; Citation2020) and links to O’Gorman’s focus on ‘bird-centrism and multiscalar politics’, the latter of which we frame herein in terms of the materiality that can be read through the regulatory regime (O’Gorman Citation2021, chapter 6). Our identification of a selective-ness of the management regime is described as ‘bird-centrism’ by O’Gorman (Citation2021, 143), who observed in her reflection on the evolution of the wetlands protected area category that ‘ … in the 1960s and 1970s, wetlands gathered meaning as valuable primarily as bird habitat. The wetland category too shape within particular knowledge practices, namely those of the sciences.’. Inspired by such critical reflections about watery engagements in an Australian context (McLean et al. Citation2018; O’Gorman Citation2021; Potter et al. Citation2022), we endeavour to demonstrate herein how Sydney’s only urban Ramsar Wetland is a product of particular management approaches (at best), and, (at worst) benign neglect. We then argue that a reframing to place more-than-human rights as the primary concern of management approaches through a ‘rights’ approach, as suggested by key wetland researchers, might enable management practices to be re-prioritised for the benefit of both human and more-than-human communities.

From ‘rights of nature’ to ‘rights of wetlands’

We suggest that there is a need to re-conceive environmental protection laws and actions to give voice to wetlands as ecosystems, rather than as habitat spaces for individual species. In this context there is also a growing recognition, and greater appreciation, of the need to think about discrete environmental rights for non-human entities, beyond the anthropocentric focus of a classical human rights discourse. This evolution has been mirrored in the changing institutional arrangements within the United Nations’ institutional structures, for example, the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights (OHCHR) created an Independent Expert for the Environment (Prof John Knox) over a decade ago (2012) and which has been subsequently upgraded to a Special Rapporteur with a brief to continue to advise on the environmental rights/degradation nexus. In recognition of the evolving mainstreaming of the human rights and environment nexus, in July 2022 the United Nations General Assembly passed a Resolution (A/RES/76/300) recognising the human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment (United Nations Citation2022).

Going beyond these advances in an anthropocentric framing of the human rights/environmental nexus has pushed a further narrative towards rights for nature, in and of itself, rather than through the humanistic lens of the dominant human rights paradigm. The evolution of anthropocentric human (environmental) rights towards the inclusion of non-human rights has been influenced by a broader movement under the ‘Rights of Nature’ (RoN) rubric. This evolution reacts to the anthropocentric assumption that humans are separate from, and superior to nature, which used to justify the view of nature as a type of ‘property’ to be owned, controlled and exploited, primarily for economic gain and to support a booming human population (Boyd Citation2017). Geographical scholarship has long explored this false dichotomy (see, for example, Castree et al. (Citation2016) or Braun (Citation2016)). In a regulatory sense, RoN means reconceptualising what it means to be legal rights-holders by transforming the view of nature as an object of property rights to legal subjects that possess their rights and conferring responsibility to humans to uphold them (Boyd Citation2017).

The RoN approach has found support in cognate waterscape work, particularly in the call for a right to think about rivers as living beings (as previously mentioned, see O’Donnell Citation2020). Some scholars reflect on the evolution and extension of legal ‘rights’ (‘personhood’) for river systems and lakes (for example, see Charpleix Citation2018; Macpherson Citation2021; O’Donnell Citation2020; Citation2023). O’Donnell (Citation2023, 118) concedes that this scholarship ‘is a space defined by legal creativity and experimentation. … driven by the desire to effect change.’ While the exact type of recognition (personhood to an entity, following O’Donnell Citation2020) varies, each re-framing label carries with it a desire to place the water body at the centre of entitlement to exist and flourish – the essence of any RoN claim.

Using a RoN approach places flora and fauna at the centre of environmental regulation. This perspective also aligns neatly with emergent calls for reframing wetlands governance through a ‘rights’ lens. A ‘Rights of Wetlands’ (RoW) idea has been pioneered by scholars such as Davies et al. (Citation2021) with their proposal for a ‘Universal Declaration of the Rights of Wetlands’. They argue that current and historical approaches to environmental conservation and management have proven to be inadequate for wetlands (Davies et al. Citation2021). A call for a ‘Universal Declaration of a Rights of Wetlands’ asks for a reconsideration of the management of wetlands through a paradigm shift away from the maintenance of ‘ecological character’ and ‘wise use’ approaches that dominate Ramsar governance regimes (Davies et al. Citation2021; Finlayson et al. Citation2021 and see Kumar et al. Citation2020). Instead, Davies et al. (Citation2021) and Finlayson et al. (Citation2021), support a ‘Rights of Wetlands’ with a proposed 8-point declaration,

The right to exist

The right to their ecologically determined location in the landscape

The right to natural, connected and sustainable hydrological regimes

The right to ecologically sustainable climatic conditions

The right to have naturally occurring biodiversity, free of introduced or invasive species that disrupt their ecological integrity

The right to the integrity of structure, function, evolutionary processes and the ability to fulfil natural ecological roles in the Earth’s processes

The right to be free from pollution and degradation

The right to regeneration and restoration (Davies et al. Citation2021, 598).

These authors have extensive experience in wetlands science and policy and make clear their views on the urgent need, in a time of adverse climate change impacts and a biodiversity crisis, that wetland protection must be reformulated to better meet future challenges. Intrinsic to their approach is to recognise that giving wetlands ‘rights’ ‘ … will provide a timely basis for a step-change in effective and morally robust re-visioning of the human relationship with wetlands’ (Davies et al. Citation2021, 597). Existing governance arrangements, led by the 50 + year old multilateral environmental agreement (the Ramsar Convention), do not meet today’s climate and biodiversity crises. A rights framing takes the idea of legal personhood (in the form of a ‘naturehood’) to enable wetlands to prosecute their entitlement to exist and flourish. Such an approach also recognises the intrinsic connection between humans and wetlands as interdependent. The problem of a continual loss and decline in wetlands habitats necessitates the need for a governance rethink for the regulation of these crucial places (Gillespie Citation2018; Citation2020; Citation2022).

Wetland protection and regulation

For the past 50 years, recognition of the importance of wetlands has been prevalent in globally coordinated efforts to protect them, in large part attributable to the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat (Ramsar Convention) (Ramsar Convention Citation1975). The Ramsar Convention recognises the importance of wetlands as regulators of water cycles, as habitats for flora and fauna (especially waterfowl), and for their economic, cultural, scientific, and recreational value. Furthermore, wetlands have been related to the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and targets (Ramsar Secretariat Citation2018; Samaneh, Nockrach, and Kalantari Citation2019). More recently, the 2021 Global Wetland Outlook emphasised the critical role that well-managed, intact wetland environments play in the prevention of water-borne and zoonic diseases, climate change mitigation, climate change solutions, and in achieving water and food security, all of which are global challenges of the twenty-first century (Ramsar Secretariat Citation2021).

The importance of wetlands protection has been translated into domestic policy contexts all over the world. To date, 172 countries have ratified the Convention and there are 2455 sites covering 255,792,244 hectares on the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Secretariat Citation2022). Australia alone has 66 Ramsar wetlands covering 8.3 million hectares that are subject to strategically implemented management plans for their conservation and wise use (DCCEEW Citation2023). However, there remain ongoing challenges. In the last 50 years, the world has seen a decline of at least 35% of natural wetlands and an increasing extinction risk of wetland-dependent species (Davidson et al. Citation2020). They are increasingly threatened by overuse, agriculture and unfettered development, pollution such as pesticide runoff, plastic and pharmaceutical residue, and the impacts of climate change such as increases in sea surface temperature, acidification, rainfall, desertification, coastal erosion and sea level rise (Ramsar Secretariat Citation2021). Unfortunately, there exists an ‘implementation paradox’ (Finlayson Citation2012) where wetlands continue to suffer despite their extensive protection regimes. As previously mentioned, we suggest that there is a problem in approaching wetland protection from a selective, curated threatened species approach.

These challenges are apparent in an Australian context. We note that Australia was one of the first signatory countries to the Ramsar Convention, yet Australian wetlands, like those around the world, are under increasing threat of ecological deterioration. We focus our attention on a case study of a Ramsar-listed wetland, the Towra Point Nature Reserve (TPNR), located in Botany Bay (Kamay) of Australia’s largest urban city, Sydney, and capital of the state of New South Wales (NSW). Across Botany Bay, only fragmented remnants of the Botany Bay wetlands still exist after being buried beneath suburbia, Port Botany, and Sydney Airport (Hamilton et al. Citation2020).

Case study: Ramsar-listed Towra Point nature reserve Sydney, Australia

TPNR is a coastal wetland environment located on the Kurnell Peninsula in Botany Bay (Kermode et al. Citation2016; see ). Covering 632 hectaresFootnote1, TPNR provides or contributes to various ecosystem services including food production, regulation of hydrological regimes, recreational, scientific, educational, aesthetic and heritage values, nutrient cycling, and habitat for threatened species and ecological communities (DECCW Citation2010).

The value of TPNR, especially to humans, has been long recognised. The presence of shell middens, rock shelters, engravings and burial sites indicates the significance of this environment to the Dharawal people (DECCW Citation2010). During the invasion, TPNR was one of the first places where European scientists took botanical and zoological samples and later it became a significant site for timber, sheep and oyster farming (DECCW Citation2010). In 1975, almost all land uses, aside from some small oyster farm operations, were restricted when part of the wetland was dedicated as a nature reserve before it became a Ramsar wetland (NPWS Citation2001). There are many intersecting conventions, agreements, laws and planning instruments that contribute, directly and indirectly, to the protection and management of TPNR (see ). Australia translates her Ramsar Convention wetland protection obligations into the domestic context through the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act).

Table 1. Conventions, agreements, laws, and planning instruments directly and indirectly related to the protection and management of Towra Point Nature Reserve.

These rules, regulations and laws provide an extensive network of protective mechanisms for the wetland. However, despite this extensive protection in law, like many of the world’s wetlands, the declining health of TPNR continues. In 2017, the severity of ecological decline was formally realisedFootnote2 when the Administrative Authority for the Ramsar Convention in Australia submitted a statement of reasons for the likely a change in ecological character and a notification of change in ecological character for TPNR to the Ramsar Secretariat in accordance with Article 3(2) of the Convention. In other words, the Ramsar Secretariat was officially notified of TPNRs ecological deterioration. The reporting of the deterioration was done in accordance with the National Guidance on Notifying Change in Ecological Character of Australian Ramsar Wetlands. This is a framework for identifying, assessing, and notifying the Ramsar Secretariat of the state of Ramsar-listed sites (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2009). The 2017 notification identified that TPNR had exceeded various ‘limits of acceptable change’ established in the original ‘ecological character description’. For example, it has surpassed a 50% decline in the abundance of shorebirds over five consecutive years when there was supposed to be no decline at all (Australian Government Citation2017).

Methods and methodology

Wetlands such as TPNR are suffering despite strict protection regimes. Our approach to is unpack the people-place-regulatory elements of the TPNR to enable an informed and critical assessment of the efficacy of its protection. To achieve this, we employed three complementary methods to shine a light on various facets of the human--nature relationship at TPNR.

Our first method, adopted to gain a critical understanding of the policy and regulatory context that guides the protection and management of TPNR, involved a qualitative content analysis of the policy and regulatory settings for the wetlands (Palmer Citation2017). Such an approach drives much legal geography scholarship, especially that which aims to reform environmental regulation (see, for example, Bartel (Citation2016)). Thirteen policy and legislative documents for TPNR were analysed using a qualitative content analysis approach (the documents are listed in , above). Qualitative content analysis involves the deconstruction and subsequent coding and analysis of written sources to reveal latent meanings (Baxter Citation2009). The analysis involved a text search query in NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software (QSR Citation2022), using key words. The query highlighted the key words and related sections, paragraphs and sentences that were coded to the words and organised into themes and sub-themes, parent codes, and child codes in NVivo. Although preliminary themes were established, the coding was an iterative process, so they were developed, reorganised, and reworked (rephrased, re-defined, excluded) as they became more apparent in the texts (Blair Citation2015). This approach was chosen to address a common criticism of coding that the selection of codes is based on subjective judgements about what categories of data are important to the research (Linneberg and Korsgaard Citation2019). Arguably the inductive approach enabled more reflexivity as the codes could be reworked when any predisposition became apparent. Our approach to coding drew on Hall and Steiners (Citation2020) analysis of sub-national policies about pollinator insect decline. We acknowledge that there are more sophisticated uses for NVivo (see, for example Liu et al. (Citation2020)), however, we suggest our basic coding and analysis process was appropriate here due to the narrower scope of documents and the qualitative nature of the analysis (Hall and Steiner Citation2020).

Our second method involved field-based observations. Twelve field trips were undertaken over three months from late July to early September 2022. During these trips we used a photo voice method to record our encounters within the wetlands. A major challenge that geographers, environmental studies scholars and environmental legal researchers face is how to transcend the anthropocentric gaze and representation to meaningfully recognise and incorporate nature’s agency into research (Dowling, Lloyd, and Suchet-Pearson Citation2016; Gibbs Citation2020). We responded to this challenge by adopting a photo voice method to engage with the more-than-human dimensions of TPNR. It was imperative to do because we want to centre nature’s voice. Our use of this method was inspired by some recent innovations in geographical practice. For example, Keating (Citation2019) has used ‘non-human photography’ to overcome human privilege in research by focussing on the intensities of the image and therefore opening the perceptive experience to one more sensitive to nature’s narratives. Intensity describes the affective relationships between human and non-human beings and their capacities to act and be acted upon (Margulies Citation2019). Keating (Citation2019) shows that through images, we can transcend representation and the anthropocentric gaze that is otherwise prevalent in textually based research methods, and better attune to the narratives of nature in the context of its affective interactions with humans and human institutions. Our field-based observations captured the wetlands through photographs, sound recordings and descriptive fieldnotes, adopting a similar approach taken by Margulies (Citation2019). Each trip was approximately 7–14 days apart, with timing determined by factors such as whether, availability of volunteers and equipment, and personal injury or illness. It was important to complete multiple trips to attune to the physical realities of the wetlands place (Derr and Simons Citation2020). The original intention was to access the reserve by land via the restricted land-based part of the wetland, however, we were unable to secure permission to use this access, so field observations via publicly accessible areas of the reserve were undertaken, which included three land-based locations as well as water-based access via boating and kayaking. Land-based trips were also made to publicly accessible parts of Woolooware Bay to explore the western side of the reserve. Analysis of the field-observations involved studying the images, sound recordings and fieldnotes to extrapolate meaningful observations. Through this method, TPNR could be studied in its natural setting, or in the words of Gibbs (Citation2020), in a ‘beastly place’. We drew on Gibbs (Citation2020) for such an approach is inherent in centring nature’s agency in research so that it can co-produce knowledge.

Our third method involved seven semi-structured in-depth interviews with key stakeholders. Interviews were conducted to explore the attitudes held by the people who are involved in protecting and managing TPNR. Potential participants were identified based on their involvement in TPNR currently, or in the past. Key stakeholder participants included environmental consultants, elected representatives, former government employees and conservation volunteers. Interviewee identities have been protected in accordance with the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee Approval number 2022/414.

The need for a different approach

We found that there was an extremely low-level of engagement with the policy and regulations designed to protect this environment. This was exemplified by the absence of ‘Montreux Record’ (MR) status for the ecologically compromised wetland. As previously mentioned, despite the recognition of ecological decline of the TPNR in 2017 it was not listed in the MR and remains absent in the latest record (Ramsar Secretariat Citation2022). Examination of key policies () also revealed other interesting points. It is noteworthy that under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW), TPNR is under the care, control, and management of the Secretary (or a Board of Management designated by the Secretary)Footnote3 who must prepare a Plan of Management (PoM) outlining the management principles and objectives for the site.Footnote4 PoM’s expire on the 10th anniversary of their implementation.Footnote5 However, the current PoM for TPNR was adopted in 2001, meaning many of its details are outdated, including information on its ecological health and management strategies.

We question what is going amiss between the way we value wetlands on paper and how these commitments are operationalised. There is an invisibility of TPNR that was observed through the interviewees, who explained there is a lack of proactive protection for TPNR beyond on-paper legal requirements, a deficiency of volunteers to implement management actions, and a low-level of awareness about the importance and even existence of TPNR from the public. By way of example, one interviewee observed that,

I suspect if you asked your average person in the block of units down there, did they realize that they have an obligation to be contributing to the long-term maintenance of that foreshore. I think they'd go ‘what? No one told me that’. [P2]

We suggest that the approach of benign care and neglect evidenced at TPNR is also reinforced by the protection of the waterscape in terms of a discrete focus on the importance of iconic species in wetlands management. Certain types of ‘nature’ are prioritised. As interviewees P2 and P4 (amongst others) stated,

I don't think there is a single most important thing, I think you've got to treat it as an ecosystem … there's enough space there to have ecosystem services and you know, there's so many things that Towra Point offers beyond threatened species or migratory species. P2

… what's actually really important for Towra is the whole package, not just the fact that there's a bunch of animals that have international status … it’s about diversity and productivity. It's not about the iconic species. P4

Our analysis of the policy and regulatory texts revealed that the human--nature challenges within the TPNR stem from a relationship that is institutionalised through this policy and regulatory context. For example, conservation is targeted towards particular species ‘types’. In the policy context for TPNR, this is often migratory species, especially shorebirds. Such an emphasis is not surprising given that instrument such as the Ramsar Convention targets waterfowl and CAMBA, JAMBA and ROKAMBA () each similarly promote the protection of migratory birds. Other regulator instruments reveal biases. The language of, for example, the LEP 2015 which aims to protect ‘areas of high ecological, scientific, cultural or aesthetic values’ or the SEPP 2021 which aims to conserve the ‘natural’ environment both establish conditions about what is, and is not, valuable in terms of conservation. The texts reinforce the notion that nature must be ‘significant’, ‘important’, ‘natural’ or ‘unique’ to be of value and to be thus afforded any protection. With these descriptors the language within the regulatory and policy texts marginalises common, non-migratory, non-threatened and non-native species within these land/waterscapes by not valorising these ecosystem elements. Ultimately, the regulatory system prioritises what is deemed ‘worthy’ of conservation and in turn this process marginalises other categories of nature that are ‘ordinary’ or ‘common’. Arguably, if we are going to care for the interconnected wetland, we need to overcome these value hierarchies.

Conclusion

The loss and decline of wetlands cannot be ignored. Since the introduction of the Ramsar Convention over 50 years ago, the world has lost at least 35% of its natural wetlands, which has had devastating consequences for both the human and non-human populations that depend on them. There is, evidentially, something amiss between the existence of wetland regulation mechanisms and their implementation. This research reinforces the importance of forging connections with ‘shadow places or waters’ (McLean et al. Citation2018) like TPNR which are messy, complex urban waterscapes that lack the typical characteristics to generate positive human-nature connections (Gillespie Citation2020). By, in effect, barricading humans from TPNR, we restrict the opportunities for people to garner a sense of appreciation for the wetlands, and such an appreciate is necessary for motivating the protecting of these places. Moreover, idealisations of selective elements of the wetlands, through a hierarchy of protective categories, such as iconic waterbird species, in our regulations and policies contributes to our ignorance of the holistic value of TPNR. Through management, we appear to be preserving an ‘ideal’ type of nature (recalling O’Gorman’s Citation2021 ‘bird speciesism’) which, in turn, renders other, ‘ordinary’ aspects of the wetlands invisible. This is dangerous for a place like TPNR because conservation is reliant on human intervention, and if these interventions fail, further degradation of the land and waterscapes are likely to follow. The operationalisation of the law may cement the wetland’s perceived status as a ‘shadow waters’ (McLean et al. Citation2018) in a ‘crappy’ scape (Urban Citation2018).

We suggest that in order to reinvigorate the conservation of complex urban wetlands the potential of both a RoN and, nextly, a RoW is useful to explore. A RoW approach could help dissolve the binary established in law and elevate the needs of nature, address the source of the degradation of wetlands and undo the hierarchical assumptions about what is and is not worthy of active management. The aim is to forge greater connections to wetland environments. This is a complex and ambitious undertaking (O’Donnell Citation2023). However, given the failings of current regulatory regimes, we suggest it is now time to rethink how we approach wetlands care and protection. A RoW Declaration has the potential to provoke a shift in the human-wetland relationship to craft greater reciprocity and respect where wetlands are afforded inherent rights, rather than conferred or granted rights. Such an approach can invoke duties and responsibilities upon humans to protect or act as guardians or stewards of protection (Davies et al. Citation2021). Finlayson et al. (Citation2021) claims it will generate the paradigm shift required to increase management capacities for wetlands, reverse biodiversity loss and climate destabilisation, and better integrate humans and nature by dissolving the binaries that presuppose humans as the sole possessors of personhood and rights. Recognition of TPNR’s rights, following the RoW approach, might enable the place, in its entirety, to be seen as worthy of protection as a waterscape habitat in all its modified and messy form. Ultimately, such an approach could enable advocacy on behalf of the wetlands themselves to ensure the place is given a voice in ongoing management approaches.

It is critical that we bring wetlands out from the ‘shadows’ if we are to guarantee the protection of these waterscapes. Negative human perceptions of wetlands are a major factor in our failure to adequately regulate them. We must institutionalise greater connections with this environment if we are to safeguard them. We also contend that the binary between ‘valuable’ and ‘crappy’ natures generated through the unequal categorisations of nature in law could be remedied by drawing attention to the nonsense of hierarchically separating humans from nature, and nature from nature. It is time to rethink our regulation of wetlands by moving towards a Rights of Wetlands to redress regulatory shortcomings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alyssa McDonald

Alyssa McDonald completed her Bachelor of Science and Advanced Studies degree with a major and Honours (environmental studies) in the School of Geosciences, The University of Sydney, in 2022. Alyssa's research interest is the governance of wetlands.

Josephine Gillespie

Associate Professor Josephine Gillespie is an academic in the School of Geosciences at The University of Sydney. Jo is a legal geographer interested in the complex intersection of geography and law for environmental management. Jo's research interest includes the governance of protected areas, including wetlands.

Notes

1 632 hectares is the area of TPNR listed on the official List of Wetlands of International Importance published in August 2022, and the Ramsar Information Sheet published by the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage. However, the Australian Wetlands Database states 603.7 hectares, and furthermore the Plan of Management (PoM) for TPNR states the size to be 386.4 hectares, which is an outdated figure since the PoM was implemented in 2001.

2 It is worthwhile observing that some 5 years earlier, in 2012, TPNR was also presented with a Grey Globe Award, which is a monetary grant given to wetlands that have declined in ecological value as a call to action to better protect the nominated site (Wetland Care Australia Citation2012).

3 Part 4, Division 6, Section 48 National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW).

4 Part 5, Section 72AA National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW).

5 Part 5, Section 79A National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW).

References

- Australian Government Commonwealth Environment Water Office. 2017. Change in Ecological Character of the Towra Point Nature Reserve Ramsar Site - Statement of Reasons. Canberra ACT: Australian Government Commonwealth Water Office. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.environment.gov.au/water/topics/wetlands/database/pubs/23-statement-of-reasons-notification-20170807.pdf.

- Bartel, R. 2016. “Legal Geography and the Research-Policy Nexus.” Geographical Research 54 (3): 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12159.

- Bartel, R. 2018. “Place-speaking: Attending to the Relational, Material and Governance Messages of Silent Spring.” The Geographical Journal 184 (1): 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12229.

- Bartel, R., and N. Graham. 2023. “Place in Legal Geography: Agency and Application in Agriculture Research.” Geographical Research 61 (2): 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12566.

- Baxter, J. 2009. “Content Analysis.” In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, edited by R. Kitchin, and N. Thrift, 275–280. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Blair, E. 2015. “A Reflexive Exploration of two Qualitative Data Coding Techniques.” Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences 6: 14–29. https://doi.org/10.2458/v6i1.18772.

- Boyd, D. R. 2017. The Rights of Nature: A Legal Revolution That Could Save the World. Toronto: ECW Press.

- Braun, B. 2016. “Nature.” In A Companion to Environmental Geography, edited by N. Castree, D. Demeritt, D. Liverman, and B. Rhoads, 19–36. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Braverman, I. 2015a. “En-listing Life.” In Critical Animal Geographies, edited by R. C. Collard, and K. Gillespie, 203–212. London and New York: Routledge.

- Braverman, I. 2015. Wild Life: The Institution of Nature. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Carr, J. 2023. “Legal Geographies and Ecological Invisibility: The Environmental Myopia of Evidence.” Geographical Research 61 (2): 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12572.

- Carr, J., and T. Milstein. 2021. “‘See Nothing but Beauty’: The Shared Work of Making Anthropogenic Destruction Invisible to the Human eye.” Geoforum 122: 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.04.013.

- Carver, E. H., and C. Gardner. 2022. “Multispecies Conservation Movements and the Redefinition of Urban Nature at Berlin’s Tempelhof Airfield.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 5 (4): 2307–2311. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211047394.

- Castree, N., D. Demeritt, D. Liverman, and B. Rhoads. 2016. A Companion to Environmental Geography. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Charpleix, L. 2018. “The Whanganui River as Te Awa Tupua: Place-Based law in a Legally Pluralistic Society.” The Geographical Journal 184 (1): 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12238.

- Choi, Y. R. 2022. “Slippery Ontologies of Tidal Flats.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 5 (1): 340–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848620979312.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2009. National Guidance on Notifying Change in Ecological Character of Australian Ramsar Wetlands. In: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts Module 3 of the National Guidelines for Ramsar – Implementing the Ramsar Convention in Australia. Canberra: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts.

- Davidson, N. C., L. Dinesen, S. Fennessy, C. M. Finlayson, P. Grillas, A. Grobicki, R. J. McInnes, and D. A. Stroud. 2020. “A Review of the Adequacy of Reporting to the Ramsar Convention on Change in the Ecological Character of Wetlands.” Marine and Freshwater Research 71 (1): 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF18328.

- Davies, G. T., C. M. Finlayson, D. E. Pritchard, N. C. Davidson, R. C. Gardner, W. R. Moomaw, E. Okuno, and J. C. Whitacre. 2021. “Towards a Universal Declaration of the Rights of Wetlands.” Marine and Freshwater Research 72 (5): 593–600. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF20219.

- DCCEEW. 2023. Australian Wetlands Database. Canberra ACT: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Accessed July 18, 2023. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/water/wetlands/australian-wetlands-database/australian-ramsar-wetlands.

- DECCW. 2010. Towra Point Nature Reserve Ramsar Site: Ecological Character Description. Sydney: Department of Environment Climate Change and Water NSW.

- Della Bosca, H., and J. Gillespie. 2020. “Bringing the Swamp in from the Periphery: Australian Wetlands as Sies of Climate Resilience and Political Agency.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 63 (9): 1616–1632. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1679100.

- Derr, V., and J. Simons. 2020. “A Review of Photovoice Applications in Environment, Sustainability, and Conservation Contexts: Is the Method Maintaining its Emancipatory Intents?” Environmental Education Research 26 (3): 359–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1693511.

- Dowling, R., K. Lloyd, and S. Suchet-Pearson. 2016. “Qualitative Methods II: ‘more-Than-Human’ Methodologies and/in Praxis.” Progress in Human Geography 41: 823–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516664439.

- Finlayson, C. M. 2012. “Forty Years of Wetland Conservation and Wise use.” Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 22 (2): 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2233.

- Finlayson, C. M., G. T. Davies, D. E. Pritchard, N. C. Davidson, M. S. Fennessy, M. Simpson, and W. R. Moomaw. 2021. “Reframing the Human-Wetlands Relationship Through a Universal Declaration of the Rights of Wetlands.” Marine and Freshwater Research 73: 1278–1282. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF21045.

- Gibbs, L. M. 2020. “Animal Geographies I: Hearing the cry and Extending Beyond.” Progress in Human Geography 44 (4): 769–777. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519863483.

- Gillespie, J. 2018. “Wetland Conservation and Legal Layering: Managing Cambodia’s Great Lake.” Geographical Journal 184 (1): 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12216.

- Gillespie, J. 2020. “Wetlands: Protecting the World’s ‘Ugly’ Places.” In Protected Areas: A Legal Geography Approach, edited by J. Gillespie, 87–105. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Gillespie, J. 2022. “Protecting Water and Wetlands.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Sustainability, edited by R. Brinkman. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan Cham.

- Gillespie, J., R. Hamilton, and D. Penny. 2023. “Letting the Plants Speak: Law, Landscape and Conservation.” Ambio 52 (12): 470–481.

- Gillespie, J., and T. O’Donnell. 2023. “Progressive and Critical Legal Geography Scholarship.” Geographical Research 61 (2): 164–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12595.

- Gillespie, J., D. F. Robinson, and T. O’Donnell. 2024. “Insights from Antipodean Legal Geography: Building an Environmental Legal Geography Scholarship.” Progress in Human Geography. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.117703091325241229810.

- Hall, D. M., and R. Steiner. 2020. “Policy Content Analysis: Qualitative Method for Analyzing sub-National Insect Pollinator Legislation.” MethodsX 7: 100787–100787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2020.100787.

- Hamilton, R., D. Penny, J. Gillespie, and S. Ingrey. 2020. “Buried Under Colonial Concrete Botany Bay has Even Been Robbed of its Botany.” The Conversation, April 24.

- Keating, T. P. 2019. “Imaging.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 44 (4): 654–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12326.

- Kermode, S. J., H. Heijnis, H. Wong, A. Zawadzki, P. Gadd, and A. Permana. 2016. “A Ramsar-Wetland in Suburbia: Wetland Management in an Urbanized, Industrialized Area.” Marine and Freshwater Research 67 (6): 771–781. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF14307.

- Kumar, R., R. McInnes, C. M. Finlayson, N. Davidson, D. Rissik, S. Paul, L. Cui, Y. Lei, S. Capon, and S. Fennessy. 2020. “Wetland Ecological Character and Wise use: Towards a new Framing.” Marine and Freshwater Research 72 (5): 633–637. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF20244.

- Lahiri-Dutt, K. 2014. “Beyond the Water-Land Binary in Geography: Water/Lands of Bengal Revisioning Hybridity.” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 13 (3): 505–529.

- Linneberg, M. S., and S. Korsgaard. 2019. “Coding Qualitative Data: A Synthesis Guiding the Novice.” Qualitative Research Journal 19 (3): 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-12-2018-0012.

- Liu, J., G. Du, W. Liu, and D. Zhang. 2020. “70-year Evolution of China’s Environmental Policy – Based on the Analysis of Text Using NVivo 11.0.” Earth and Environmental Science 544: 12004.

- Macpherson, E. 2021. “The (Human) Rights of Nature: A Comparative Study of Emerging Legal Rights for Rivers and Lakes in the United States of America and Mexico.” Duke Environmental Law and Policy Forum 31: 327–377.

- Margulies, J. D. 2019. “On Coming Into Animal Presence with Photovoice.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 2 (4): 850–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619853060.

- McLean, J., A. Lonsdale, L. Hammersley, E. O’Gorman, and F. Miller. 2018. “Shadow Waters: Making Australian Water Cultures Visible.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 43 (4): 615–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12248.

- NPWS (National Parks and Wildlife Service). 2001. Towra Point Nature Reserve Plan of Management. Sydney: New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service.

- O’Donnell, E. 2020. “Rivers as Living Beings: Rights in law, but no Rights to Water?” Griffith Law Review 29 (4): 643–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2020.1881304.

- O’Donnell, E. 2023. “Repairing our Relationship with Rivers: Water law and Legal Personhood.” In A Research Agenda for Water Law, edited by V. Casado Perez, and R. Larson, 113–138. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- O’Donnell, T., D. R. Robinson, and J. Gillespie. 2020. Legal Geography: Perspectives and Methods. Abingdon: Routledge.

- O’Gorman, E. 2021. Wetlands in a Dry Land: More-Than-Human Histories of Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Palmer, J. R. 2017. “Environmental Policy.” In International Encyclopedia of Geography, edited by R. A. Marston, M. F. Goodchild, N. Castree, L. Weidong, D. Richardson, and A. Kobayashi. Wiley Reference Works online: John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg0468.

- Plumwood, V. 2008. “Shadow Places and the Politics of Dwelling.” Australian Humanities Review 44: 139–150.

- Potter, E., F. Miller, E. Lovbrand, D. Houston, J. McLean, E. O’Gorman, C. Evers, and G. Ziervogel. 2022. “A Manifest for Shadow Places: Re-Imagining and co-Producing Connections for Just in an era of Climate Change.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 5 (1): 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848620977022.

- QSR. 2022. NVivo (released in January 2022). QSR International Pty Ltd.

- Ramsar Convention. 1975. “Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat.” Opened for signature 2 February 1971, 996 UNTS 245 (entered into force 21 December 1975). Accessed July 20, 2023. https://www.ramsar.org/document/present-text-convention-wetlands.

- Ramsar Secretariat. 2018. “Wetlands and the SDGs. Gland, Switzerland: Secretariat of the Convention on Wetlands.” Accessed July 21, 2023. https://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/wetlands_sdgs_e_0.pdf.

- Ramsar Secretariat. 2021. Global Wetland Outlook: Special Edition 2021. Gland: Secretariat of the Convention on Wetlands.

- Ramsar Secretariat. 2022. Ramsar Sites Information Service (Online). Gland: Secretariat of the Convention on Wetlands. Accessed October 25, 2022. https://rsis.ramsar.org/rissearch/?solrsort = country_en_s%20asc&language = en&f[0] = montreuxListed_b%3Atrue&pagetab = 1.

- Samaneh, S., M. Nockrach, and Z. Kalantari. 2019. “The Potential of Wetlands in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda.” Water 11: 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11030609.

- Schmidt, J. J. 2022. “Of kin and System: Rights of Nature and the UN Search for Earth Jurisprudence.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47 (3): 820–834. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12538.

- United Nations. 2022. United Nations General Assembly Declares Access to Clean and Health Environment a Human Right. UN News Global perspective Human Stories. Accessed July 20, 2023. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/07/1123482.

- Urban, M. A. 2018. “In Defense of Crappy Landscapes.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Physical Geography, edited by R. Lave, C. Biermann, and S. N. Lane, 49–66. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wetland Care Australia. 2012. “Towra Point wins Grey Globe Aware at the 11th Ramsar Conference of the Parties in Bucharest, Romania.” Accessed October 5, 2022. http://www.wetlandcare.com/index.php/news/news-archive/towra-point-wetlands-win-grey-globe-award-at-the-ramsar-conferen/.