?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Sparsely populated geographic edges of colonised nations exhibit heterogenous historical demographic trajectories. In this study, we analyse the longitudinal evolution of the settlement system in Northern Australia to quantify and visualise relative settlement dynamics over 165 years. We extend the existing literature by deviating from analysing each township as an individual entity, instead focusing the analysis on relativities within the entire settlement system. We quantify settlement and systemic volatility through measurement and visualisation of relative settlement sizes using rank-sizes and document rank-size changes between 1856 and 2021. We analyse rapid and non-synergic shifts in rank-trajectories and demonstrate rank-trajectories for selected settlements by types. We found that the expansion of a fly-in-fly-out workforce in the resource sector since the 1980s has meant less turbulent trajectories for the settlement system in the North could potentially open prospects for more sustainable population growth policies while relocating the risks of resource dependency in employment and growing unemployment during economic bust from edges to core areas. Beyond annotating the evolution of the settlement system in Northern Australia, this study demonstrates the potential for policy, economic conditions and definitional peculiarities to affect volatility in the settlement system at geographic edges elsewhere.

Introduction

Sparsely populated geographic edges in developed nations, such as Alaska, Northern Canada and Northern Australia, have and continue to hold national significance as resource regions and are often proffered as ‘natural resource banks’ (Markey, Halseth, and Manson Citation2008). This is particularly the case for Australia where the booming mineral and energy resource sector of the North underpinned the most prosperous period in the nation’s economic history during the ‘mining boom’ in the early 2000s (Tonts, Martinus, and Plummer Citation2013). Despite periods of strong population and economic growth in periods such as the mining boom, steady and sustained growth is absent in the history of northern settlements. Instead, settlements have overall come and gone, grown then shrunk or stagnated (Huskey and Taylor Citation2016). The intermittency and irregularity of both population and economic growth have led national governments to view sparsely populated areas as problematic economies (Carson Citation2011; Huskey Citation2006; Pritchard Citation2003). Settlements themselves in regions such as Northern Australia have been described as disconnected and distant economically from each other and from larger southern settlements, diminishing agglomeration effects and subjecting them to prevailing external forces for population and economic sustainability (Barnes, Hayter, and Hay Citation2001), manifesting in ongoing difficulties for population attraction and retention (Dyrting, Taylor, and Shalley Citation2020; Taylor, Thurmer, and Karácsonyi Citation2022). In this sense, the ‘region’ (for example the region of Northern Australia) is in effect ethereal; a boundary within which sets of small and dynamic settlements have existed over time (Taylor Citation2016; Wilson Citation2015).

Literature on long-term population dynamics for settlements in these edges emphasises a diversity of historical trajectories that may be evident within given regions. For example, the classical trajectory for settlements historically populated for resource extraction is hallmarked by rapid initial growth, plateauing at peak workforce, followed by rapid population declines during the end-course of the mining life cycle; often referred to as ‘boom and bust’ trajectories (Barbier Citation2005; Barnes, Hayter, and Hay Citation2001; Tonts, Martinus, and Plummer Citation2013). Such trends for resource or mining settlements in sparsely populated edges are well covered in the literature, such as for Canadian company towns (Bradbury Citation1984; Bradbury and St-Martin Citation1983; Lucas Citation1971; Porteous Citation1970) and in Australia (Lawrie, Tonts, and Plummer Citation2011; Marais et al. Citation2018; McKenzie Citation2011; Robertson and Blackwell Citation2015). However, resource-focused settlements are only one of a multitude of settlement types at edges, with the genesis of and subsequent trajectories for settlement populations multifarious (Altman Citation2003, Citation2009; Ash and Watson Citation2018; Bauer Citation1964; Kotey and Rolfe Citation2014; Randall and Ironside Citation1996; Scrimgeour Citation2007). Many enduring Indigenous settlements, for example, pre-date colonial populations as locations where people congregated to live a traditional lifestyle (Edmonds Citation2010; Paterson Citation2005; Wolfskill and Palmer Citation1981). Other settlements, which now are home to an almost entirely Indigenous resident population, were created by colonisers to specifically enact church or state policies to congregate Indigenous peoples into highly managed settlements and to influence and direct their forced assimilation (Altman Citation2003; Blomley Citation2003; Scrimgeour Citation2007; Sutton Citation2001).

Most studies seeking to understand the causes and consequences of settlement-level demographic or economic changes at geographic edges have focused on such regions or case study settlements by analysing changes in absolute population numbers and drawing links to changing commodity prices, socio-economic wellbeing and employment restructuring (Bone Citation1998; Halseth et al. Citation2017; Jackson and Illsley Citation2006; Lawrie, Tonts, and Plummer Citation2011). Alternatively, changes have been explained as being a result of resource dependency, a lack of reinvestment and subsequent economic volatility in the region (Markey, Halseth, and Manson Citation2008; Pritchard Citation2003; Tonts and Plummer Citation2012). Consequently, there is a gap in understanding the relativities and synergies within and hierarchic evolution of settlement systems at edges. This reflects the considerable diversity of settlements and the tendency for policy to regionalise solutions to complex and interrelated settlement-level dynamics (Pritchard Citation2003; Robertson and Blackwell Citation2015; Wilson Citation2004).

While a summary on the specificity of settlements at geographic edges was provided by Taylor (Citation2016), who distilled the learnings from existing case studies, this work was synthesising rather than analytical. Similarly, Huskey and Taylor (Citation2016), Marais et al. (Citation2018), Tonts, Plummer, and Lawrie (Citation2012) distinguished and discussed resource, Indigenous and governmental--military settlements in a systematic way, while Carson et al. (Citation2011) described the diversity of settlements at edges in their demographic compositions and population progressions. More recently, the volume of research on population change for edge regions has grown (Le Tourneau Citation2020, Citation2022), with a focus on drivers for attraction and retention for individuals and their families, as policy makers seek to increase both (Taylor, Thurmer, and Karácsonyi Citation2022).

In this study, we analyse long-term relative dynamicism for settlements at the ‘edge’ of Australia to empirically demonstrate and measure rapid and non-synergic shifts in hierarchic trajectories for settlements and their groups and measure the changing sums of these hierarchic shifts within the settlement system over time. While understanding relative hierarchic changes supplements existing knowledge about the diverse and volatile demographics of such settlements (Carson et al. Citation2011; Taylor Citation2016), their low population retention rates (Dyrting, Taylor, and Shalley Citation2020) and document relative trajectories by differential settlement-types, analysing sums of rank-shifts change over time provides a quantitative measurement for the evolution of and changing volatility within the settlement system as a whole. This is new since the evolutionary models for settlement at edges such as by Lucas (Citation1971), Bone (Citation1998), Randall and Ironside (Citation1996) explained demographic trajectories for individual settlements using absolute population and economic measurements, rather than explaining the evolution of the settlements as part of a system in a relativistic way.

We focus the study on Northern Australia using a method of analysing and visually modelling historical data – involving measurement of rank-size changes and a modification of rank-clocks, first introduced by Batty (Citation2006). Rank-clocks are radial charts, which facilitate visualisation of changing settlement’s rank-size positionalities on a time-scale continuum, while calculating sums of rank-shifts facilitates the analysis of changing characteristics of the entire settlement system, or for clusters of settlement types within the region. Longitudinal measurement of changing relative settlement positionalities and rank-shifts is valuable for assessing the tenet of existing literature which proffers that settlement populations in sparsely populated edges are dynamic and delicate to the extent that settlements can be considered as ‘beyond’ the rural-peripheral bound, having populations with observable and extreme flux, both within and across time periods (Carson Citation2011; Carson et al. Citation2011; Thurmer and Taylor Citation2021). With longitudinal data available, we hypothesise that rank-clocks and sums of rank-shifts over time will reveal volatile and turbulent trends in the micro-dynamics for individual townships, as well as identifying changes in the scale of volatility over time through consolidation of the settlement system.

To establish the full context for this study, we first examine relevant scholarship on settlements at edges as they relate to their diverse demographic trends. We then explain the data sources and tailored quantitative methodology for ranking, rank-clocks and measuring rank-shifts before presenting the results. The discussion and conclusion section closes the study by outlining how the research herein might influence policies for sustainable demographic progression for different types of settlements at edges, as well as the limitations of and further research opportunities extending from this study.

Population trajectories for settlement in sparsely populated edges

Settlements in sparsely populated edges of colonised nations experience dynamic shifts in their small population numbers arising from internally generated conditions or structural economic changes. These often produce migration flows, which deviate from past states, such as from stable to unstable change, or from low to high flows. In examining regional trends, quantum shifts for individual settlements may be missed by policy makers, as micro-trends become ‘averaged out’ of analysis, resulting in policies that may be misaligned with actual trends and issues; and which may ultimately fail to ‘make a difference’ (Carson et al. Citation2011; Kauppila Citation2011; Taylor et al. Citation2011). As Carson et al. (Citation2011) have highlighted towns at such edges did not emerge through market processes to become service and population hubs. Instead, most were settled and populated opportunistically based on beneficial factors, such as the presence of natural harbours, proximity to water, suitability and importance of location for military purposes, or the presence of mineral resources.

As might be expected, over time many factors can diminish or enhance the significance of the original purpose for individual settlements, potentially leaving no market processes to sustain it economically (Hayter and Nieweler Citation2018; Keeling and Sandlos Citation2017). Furthermore, settlements at edges are poorly connected to each other, such that internal economic linkages are weak with precarious regional economies of scale and fractured transport networks (Carson, Carson, and Argent Citation2022) and are distanced from centres of financial, economic and political power (Carson and Cleary Citation2010). Aside from demographic and economic shifts, individual settlements, under the circumstances described here, may become enclaves within edges and exhibit different and diverse demographic pathways and compositions to elsewhere in the region (Pritchard Citation2003; Taylor Citation2016; Wilson Citation2004). For example, long-range connections, such as the movement of fly-in-fly-out workers (Houghton Citation1993; Storey Citation2001, Citation2010; Storey and Hall Citation2018) make mining towns and camps disconnected from local Indigenous communities (Langton and Mazel Citation2008), turning them into enclaves for the non-local workforce (Carson Citation2011; Ferguson Citation2005; Hayter, Barnes, and Bradshaw Citation2003).

Human settlements at geographic edges can be reasonably classified as either single-industry dominated resource towns, which are at the same time might be significant service centres for their hinterland communities (Robertson and Blackwell Citation2015), government towns, including administrative centres and military outposts where the public sector plays a significant role (Pritchard Citation2003; Randall and Ironside Citation1996), or Indigenous communities characterised by marginalised Indigenous residents (Altman Citation2009; Carson and Cleary Citation2010). Land use activities may be limited to fishing, hunting, forestry, burning and cattle grazing (Holmes and Lonsdale Citation1981), although in general, agriculture has not historically attracted significant settler populations. In this sense, few settlements at the edge transition into ‘rural’ settlements that have identifiable economic connections to cores of economic activity (Ash and Watson Citation2018; Bauer Citation1964). Instead, edges are often viewed from outside as hostile and uninhabitable environments (Le Tourneau Citation2020).

Sourcing and ordering data to systematically analyse historical population trajectories for individual settlements and settlement types is a complex task. Bone (Citation1998), for example, provided a systematic classification for resource towns in the Mackenzie Basin (Northern Canada), highlighting that their diverse population trajectories cannot be described by a single model, distinguishing boom–bust towns, towns of uncertainty, diversified towns and sustainable towns. Others have attempted to explain the different stages of resource town development and the rejuvenation and transition (‘normalisation’) of resource towns from the company into open towns (Hayter and Nieweler Citation2018; Marais et al. Citation2018) as a function of overall changes in socio-economic policies (Halseth and Sullivan Citation2004; Jackson and Illsley Citation2006). More recently economic diversification as a means of survival for resource towns (Keeling and Sandlos Citation2017), localised circumstances and institutional frameworks (Tonts, Martinus, and Plummer Citation2013; Wilson Citation2004), along with place-based development have gained academic attention for explaining population changes for resource towns (Halseth et al. Citation2017). Additionally, Houghton (Citation1993) and Storey (Citation2001), highlighted the loss of benefit from mining booms for remote regions through long-distance commuting where the ‘fly-over’ of capital constraints regional development. Extending this, Storey (Citation2023), and Storey and Hall (Citation2018) described the emergence of ‘no-town’ mineral resource extraction processes from digitalisation of the mining workforce and remotely located technological mining processes. In contrast, Pritchard (Citation2003) and Tonts, Martinus, and Plummer (Citation2013) emphasised the dual economic structure in remote regions where a significant public sector exists focusing on welfare services, especially for disadvantaged Indigenous people. Indeed, the government sector often plays an important role in the attraction and retention of labour and therefore population.

To extend our understanding of changes in the settlement systems at edges we systematically analyse and visualise the long-term relative trajectories for Northern Australian settlements by measuring sums of rank-shifts and applying rank-clocks to a longitudinal data set that we have constructed for this study and will describe forthwith.

Materials and methods

In this study, census data is used to represent changing hierarchic patterns in the settlement system in Northern Australia over a long timeframe by visualising the results using rank-clocks (Batty Citation2006). Mathematically, rank-clocks are based on Zipf’s Rule. First described by Zipf (Citation1949), this rule specifies that there is significant scaling of human-derived objects and events, such as cities, firms, building heights and even the occurrence frequency of words in a book, in the upper tails of their size – or frequency-distributions (Batty Citation2006; Havlin Citation1995). Rank-clocks can be used in the analysis of any of such objects and events, requiring only that elements are arranged in a decreasing rank-order by their size (Batty Citation2010, Citation2015). They have been applied for diverse purposes (Huang et al. Citation2015; Xu, Sun, and Zhao Citation2021), such as the analysis of tourism flows (Guo, Zhang, and Zhang Citation2016) and in combination with other geo-visualisation methods to deliver analytical results (for example, Jażdżewska Citation2017).

Ranks in rank-clocks are calculated by ranking each township in a region based on its population size at the time of each population census, where the most populous settlement is assigned rank 1, followed by ranks 2, 3 and so on. The advantage of representing townships by rank-sizes is that it allows one to compare settlements by their relative hierarchic positionalities within the settlement system, regardless of the changing total population for the entire settlement system over time. Rank-clocks allow readers to follow the ‘micro-dynamics’ of individual townships, groups of townships and rank-size changes for a whole region.

Rank-clocks visualise individual observations by assigning different colour schemes to comprise a collage of rank-trajectories for individual observations (Batty Citation2006). The colour is based on the census year of the first population number record and the rank of the town at the time is based on its population size. The colour scheme for additional towns entering the rank clock is usually assigned by rainbow order.

From ordering the data to become an input to visualising it using rank-clocks we can conduct statistical analysis to extend the results. This includes measuring average intercensal rank-shifts amongst settlements which can be expressed as the mean absolute sums of rank-sifts proposed by Batty (Citation2006),

where r is the rank of i town at t time.

For tracking long-term changes in hierarchic patterns of settlement systems at edges, Northern Australia was considered a fit-for-purpose case study area for several reasons. Firstly, Northern Australia has existed as a loosely integrated frontier throughout the twentieth century (Carson Citation2011), and to the present day has been subject to boom–bust cycles, large-scale regional development initiatives and policies, modernisation and socio-economic integration measures. Each of these has, over time, significantly influenced population sizes and settlement characteristics (Taylor Citation2016; Taylor et al. Citation2011).

Secondly, historical township-level population data for Northern Australia were collected on a regular basis even before the first Commonwealth Census in 1911. Census records for townships are available back to the second half of nineteenth century, which we accessed in the Historical and Colonial Census Data Archive (Smith, Tim, and Stuart Citation2019). This is an open access data repository where census data were collected for townships in Queensland (1856, 1861, 1871, 1886, 1891, 1901), Western Australia (1970, 1881, 1891, 1901) and in the Northern Territory – at that time part of South Australia (1891, 1901) – enabling us to utilise this as the main and consistent source of data. In comparison, census counts were first available for Alaska from the 1880 US Census, for the Northwest Territories (Canada) for 1881, and Siberia from the 1897 Russian Census. As such, township-level census data available for Northern Australia (1856–2021) is to some extent the longest existing time series for areas that might be described as present-day geographic edges (Karácsonyi and Taylor Citation2023).

To understand rank-trajectories for individual townships and to demonstrate the evolution of the settlement network, total census population numbers for townships were used in this study. For the 2006 census onwards, usual resident population numbers at census night for ‘Urban Centres and Localities’ (UCLs) were used. For censuses 2001 and before the census population numbers available for localities (towns and cities) were used. The changing definitions for localities are summarised in . Localities for the entire Northern Australia, geographically defined by the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (NAIF) Act 2016 (Government Citation2016), have been included if they were reported in any censuses by and before 2021 (). In total 352 settlements (townships, municipalities, urban centres, bounded, rural and other localities) were identified within Northern Australia with a population number available for at least one census between 1856 and 2021 and formed the basis to calculate settlement-rankings. Among these 352 settlements, 300 were included in the 2021 census covering 85% of the total usual resident population of Northern Australia at the time. The remaining 52 settlements were either uninhabited (ghost town) or had a small population not qualifying them for being considered as localities in 2021 (see ). Visualisation of rank-trajectories for these localities and measurements of rank-shifts are outlined in the next section.

Table 1. Minimum definitions for townships/localities in commonwealth censuses.

Results

Rank-trajectories in the settlement system of Northern Australia

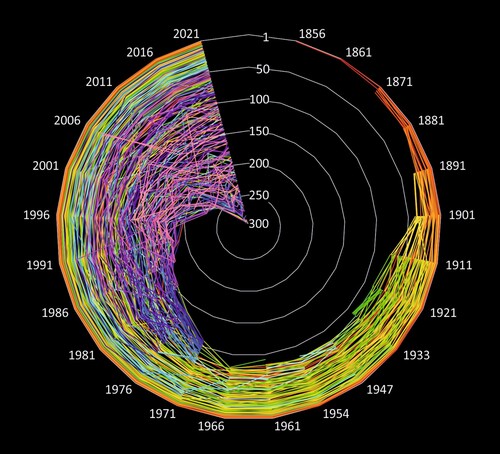

In Northern Australia, 352 settlements were identified as having a population record for at least one census between 1856 and 2021. Among them there were 316 settlements with a population recorded for at least two consecutive censuses, enabling their rank-trajectories to be presented in the rank-clock ().

As expected, some of the early towns, though significant at the time, moved quickly downwards in ranks while new townships emerged at lower levels. For example, large numbers of new observations entered the rank-clock in 1911, as demonstrated by the expansion of the number of lines for this year in , when the first Commonwealth Census was conducted incorporating the geographical classification of urban centres and localities (). Likewise, from 1971 onwards, mining camps emerged in the census as townships, as a result of the introduction of comprehensive geographic and population criteria for bounded localities (Linge Citation1965). After the 1967 national referendum, in which Australians voted overwhelmingly to amend the Constitution to allow include Aboriginal people in the Census of Population and Housing conducted, 1971 was the first Census to do so, then in 1976 enumeration in remote and northern Australia was more comprehensive and included several more Indigenous communities. Indeed, some new settlements, such as Karratha (pop. 17,013 in 2021), the iron ore export port established in 1968, and Mount Isa (pop. 17,936 in 2021), the copper mining and smelting town in Queensland’s Outback which was established in 1923, entered the rank-clock at a high rank, demonstrating the rapid and significant impact from mining expansion and the related workforce. This impact is demonstrated by the changing rainbow pattern in the collage, which signifies dramatic rank-shifts within the settlement system at the time.

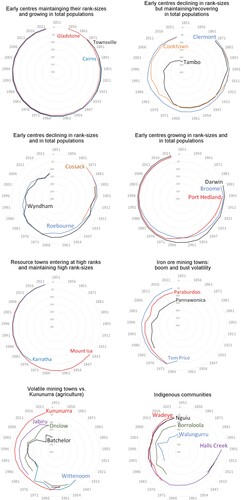

Rank-clocks also allow one to examine and visualise micro-dynamics for a single township or a small group of selected settlements. In , for example, we isolate some selected towns by settlement type, also highlighting the names of the selected localities to facilitate an easier visual interpretation of individual rank-trajectories.

The earliest established towns shown in were largely able to maintain their ranks over time. For example, the first townships in Northern Australia established on what is today the densely populated Queensland coast, such as Gladstone (pop. 34,703), Rockhampton (pop. 63,151), Cairns (pop. 153,181) and Townsville (pop. 173,724 in 2021, shown on top left rank-clock), grew over time to become cities. Others (shown on top right), such as Cooktown (pop. 1,797 in 2021) and Clermont (pop. 2,079 in 2021) declined substantially. Cooktown was settled as a military outpost for the British Navy but was later devastated by cyclones before re-emerging as a tourist town. Some centres in the Outback, such as Tambo (pop. 283 in 2021), while stable and maintaining population, declined in rank compared to others that experienced rapid population growth. Cossack and Roebourne (pop. 700 in 2021), shown on on the second row left, were the first settlements in the North of Western Australia, and became respectively a ghost town or revived as an Indigenous settlement, while Wyndham (pop. 745 in 2021) lost its importance as a port. The only large urban centre of the North outside coastal Queensland is Darwin (pop. 122,207 in 2021, , second row, right). Darwin’s steady growth in the ranks is, however, more related to large-scale policy interventions in the North which aimed at turning the city into a government service town and a resource export gateway with a focus on nearby emerging Asian economies (Taylor, Thurmer, and Karácsonyi Citation2022). With the decline in natural pearl harvesting during the first half of the twentieth century both Broome (pop. 14,660 in 2021) and Port Hedland (pop. 15,298 in 2021) declined in ranks. The slow re-emergence in the ranks for Broome from the 1960s was partly due the permission of cultivated pearl production (Moore Citation1994) while the iron ore boom in the Pilbara, resulting from the lifting the iron ore export embargo for Japan in 1960 (Marais et al. Citation2018), heralded new waves of population and settlement growth and a rapid re-emergence in ranks for Port Hedland as a major iron ore export terminal. These trend-changes in ranks demonstrate the delicate impact of policy making even at the top of settlement hierarchies at edges.

While the highest ranked resource towns, such as Karratha and Mount Isa were able to maintain their rank-positions throughout the analysis period and became the most populous mineral resource towns of the North, as well as regional service centres, there were rapid and significant swings for smaller resource towns (third and fourth rows on ). These rank-swings highlight diverse population trends among resource towns. For instance, iron ore mining towns in the Pilbara (, third row on the right) clearly follow boom and bust cycles caused by swings in mining exploration, revenues and employment as demonstrated by the bust in the late 1990s, followed by the boom in the mid-2000s, then a subsequent bust after 2008. Additionally, the peaking in global iron ore demand by the 2020s did not cause significant upheaval in the ranks. As demonstrated by the rank-clocks, the expansion of fly-in-fly-out employment practices and remote-controlled production has diminished the risks of rapid inflation in resident population numbers during booms and subsequent low population retention during busts (Storey and Hall Citation2018).

Meanwhile, a lack of sustainability is demonstrated for smaller resource towns specialising in resources other than iron ore (, bottom row on the left). These towns were subject to more extreme and non-synergic rank-shifts during boom-and-bust cycles. This included Wittenoom, the infamous blue asbestos mining town in Western Australia that opened in 1950 and was deserted by the end of 1970s. Batchelor (pop. 371 in 2021), established in 1911 as an agricultural town, was able to re-emerge as an education centre after the closing of a nearby uranium mine operated between the 1950s and 1970s. By contrast, Kununurra (pop. 4,515 in 2021), was established also as an agricultural town as part of the Ord River Irrigation Scheme in the Far North of Western Australia and experienced significantly fewer fluctuations in its population.

Conversely to the settlements above, Indigenous settlements were not systematically reported in the censuses until 1976 as they were not included in population counts for official purposes until a referendum held in 1967 yielded a pathway to do so (AIATSIS Citation2021). Some of these significant population concentrations were missions established by the end of nineteenth – and early twentieth century, with the largest number in what is now the Northern Territory. Rank-trajectories for Indigenous communities were also characterised by large swings as shown in , bottom row on the right. However, these shifts are more likely related to short-term mobilities ‘accidentally’ captured by censuses (Altman Citation2003; Prout Citation2008), to changing census enumeration procedures and variations in the quality of individual census enumeration exercises and the associated population coverage of these (Wilson and Andrew Citation2016). The adoption of a new census question (the ‘Standard Indigenous Question’) from the 1981 Census onwards (ABS Citation2014) is also thought to have created at least a partial break-in-series for census longitudinal counts of First Australians (Taylor Citation2012, Citation2011; Taylor, Payer, and Barnes Citation2018). Despite this, Indigenous communities remain more stable elements of the settlement system as they have not been as impacted by cyclical economic trends compared to resource towns.

Measuring rank-shifts in the settlement system

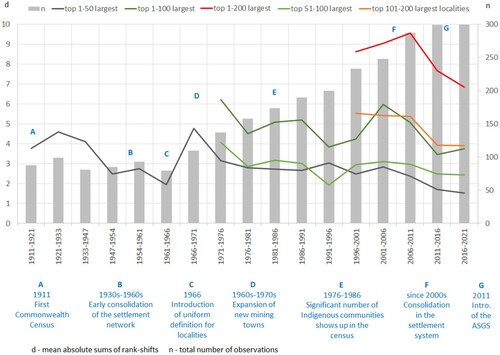

Coefficients for mean absolute sums of rank-shifts (d) are sensitive to observations entering or exiting the rank-clock, as well as to changes in the collection methodologies for the data underpinning the clocks. With the growing number of observations between 1966 (n = 80) and 2021 (n = 300) the complexity of the settlement system and thus the mean absolute sum of rank-shifts also expanded (d = 3.3 in 1966; d = 10.3 in 2021) for the entire settlement system. The number of observations were also influenced by the changing minimum criteria for being classified as locality (see ), such as by the replacement of the Linge methodology (Linge Citation1965) for determining UCLs with the ABS concept for UCLs and the introduction of ASGS in 2011.

For this reason, we dissected the rank-database and calculated rank-shifts for the top 1–50 (1911–2021), top 1–100 (1971–2021) and the top 1–200 (1996–2021) largest localities separately to provide a more robust statistical measurement by maintaining a fixed number of observations throughout the analysed periods. Additionally, calculating mean absolute sums of rank-shifts (d) for top (rank-range: 1–50, population range in 2021: 173,000–2,500), medium (rank-rage: 51–100, population range in 2021: 2,500–1,000) and low (rank-range: 101–200, population range in 2021: 1,000–350) ranked observations facilitated a better understanding of rank-shift changes withing the top, medium and bottom hierarchic sections of the settlement system in Northern Australia.

As shown in , the largest shifts among the top 50 localities in the North occurred when the expansion of large-scale mineral resource extraction commenced in the 1960s. In contrast, during the 1930s-early 1960s and since the 1980s, the settlement system was characterised by consolidation and growing synergies among the top 50 localities, as presented by the declining sums of rank-shifts. For the top 100 settlements (1971–2021, dark green line on ), more volatile rank-changes are reflected by the fluctuating sums of rank-shifts. For the 1980s this is explained by the then recently included Indigenous communities at medium and lower ranks, demonstrated by fluctuations among the top 51–100 ranked settlements. Despite these volatilities, consolidation in the settlement system can be observed since 2006–2011 for all segments of the settlement system hierarchy via reductions in new ‘entrants’ such as no new mining towns established after 1980 (Storey Citation2001) and little or no change in census methodologies or definitions.

In summary, these results show settlements with larger populations either on the top of the hierarchy of the entire settlement system, or for those on the top of their specific settlement type are seemingly more stable in their rank-sizes over time when compared to lower hierarchy level towns. Following mathematical laws, the smaller the township the larger swings in rank-trajectories which indicates the extreme fluctuation in population numbers for small settlements at the edge. Furthermore, the scale of rank-sifts decline over time is a sign that the settlement system had started ‘consolidating’ in the early twentieth century, and more perceptibly since the 2000s. It should be noted that many of the new ‘entrant’ townships from the 1960s and until the 1980s, besides Indigenous communities, were mining towns in remote Northern Australia (see Storey Citation2001; Tonts, Martinus, and Plummer Citation2013). This emphasises the turbulent impact of large-scale mining on the settlement system at edges (Lawrie, Tonts, and Plummer Citation2011; Robertson and Blackwell Citation2015; Storey and Hall Citation2018). In contrast to mining towns, we have demonstrated that townships with a workforce and economic specialisation in other sectors, such as the public sector, higher education and agriculture, proved to be more sustainable as illustrated by less volatile rank-trajectories and population futures.

Discussion

Applying rank-clocks and sums of rank-shift measurements for analysing the evolution of the settlement system in remote edges has provided certain benefits. First, it demonstrated through empirical analysis that, as proposed by Taylor (Citation2016) and Carson et al. (Citation2011), the progression of human settlement systems at edges neither represents synergic nor a continuous growth, particularly for smaller localities and at the early periods of the colonial settlement. The lack of synergies in rank-trajectories and dynamic rank-shifts within and across settlement types, time – and regional-sub-sections suggests settlements in Northern Australia are disconnected and distant economically from each other and by that there is weak regional cohesion among these places. The colour scheme (the collage of individual trajectories) of the rank-clocks do not exhibit the concentric outward pattern, which would characterise a stable-growth region and idealised rank-size distribution (Batty Citation2015). This ‘idealistic’ pattern could be expected only when the first towns remain the largest (most populous) over time by steady and growing populations as well as network densification downwards through the hierarchy to create progressively more settlements with relatively large populations, as would be anticipated and observed under conditions of continuous rural-to-peripheral settlement expansion (Bylund Citation1960). Instead, most settlements at edges have highly volatile rank-trajectories through time, making them ‘beyond’ the rural-peripheral bound (Carson Citation2011; Carson et al. Citation2011; Thurmer and Taylor Citation2021).

As demonstrated by the sums of rank-shifts, more synergic evolution can be observed only for recent time sub-sections and larger centres. This is emblematic of a slow consolidation and a more sustainable settlement system evolution. Thus, settlements on the top of the hierarchy, be they resource towns or others, are more stable in their rank-sizes over time in contrast to lower hierarchy levels. Smaller townships are documented as being more volatile, especially where resource industries dominate. The turbulent impacts of the commencement of large-scale mining on the settlement system became evident from the growing rank-shifts for the 1960s and 1970s (see Marais et al. Citation2018; Storey Citation2001). This was preceded by an early consolidation at the top of settlement hierarchy during the first half of the twentieth century that ended when mining towns entered the settlement system.

Furthermore, we have observed a consolidation in the settlement system by declining sums of rank-shifts, despite the mining boom in Western Australia since the 2000s (Tonts and Plummer Citation2012). This observation supplements the existing literature on the adverse impacts of ‘no-town’ development at edges (Houghton Citation1993; Storey Citation2001, Citation2010). We found that no-town development, the expansion of fly-in-fly-out employment practices and remote control in production have relocated the risks of inflated resident population numbers, which in turn has stabilised the population trajectories for the settlement system in the North by reducing boom and bust inflows of workers in situ (Storey Citation2010). This could potentially open-up prospects for more sustainable population growth policies while diminishing increases in the cost of living (especially housing) and male dominance during boom periods, and relocating the risks associated with resource dependency from edges to core areas (see Lawrie, Tonts, and Plummer Citation2011; Robertson and Blackwell Citation2015; Storey and Hall Citation2018). Avoiding these adverse impacts on the region, however, necessitates careful consideration of reinvestment policies (Markey, Halseth, and Manson Citation2008; Tonts, Martinus, and Plummer Citation2013) and corporate social responsibility practices to benefit the resource region and its residents (Langton and Mazel Citation2008; O’Faircheallaigh Citation2013).

While boom and bust cycles still impact economic growth in the region, uncertainties in planning for housing, infrastructure and services could be more-or-less avoided and public sector expenditures and mining royalties could be reorientated for the benefit of those in need, particularly Indigenous people (Pritchard Citation2003). Such policy reorientation could support long-term stayers and improve population retention (Dyrting, Taylor, and Shalley Citation2020; Taylor, Thurmer, and Karácsonyi Citation2022) by helping businesses and services with local embeddedness instead of attracting large-scale, unsustainable and costly infrastructure projects (Taylor et al. Citation2011).

Along with the diverse trends at lower ranks, sums of rank-shifts demonstrated a lack of synergic movement in rank-trajectories across and within settlement types (such as resource towns and Indigenous communities). This finding reflects the importance of a diverse set of factors for population change in each township (see Carson et al. Citation2011). Wilson (Citation2004), for example, stressed, resource settlements ‘ride’ on the resource ‘roller coaster’ in diverse ways depending on the companies and communities that are involved in socio-economic restructuring and the marketing and technological specificities of the mined resource itself. As we have observed from our analysis there were differences in rank-trajectories even between iron ore mining towns in the Pilbara based on diverging policies facilitated by their ‘mother companies’ (BHP or Rio Tinto) to address market changes. Furthermore, our findings reflect the importance of policy changes on population trajectories, such as for the pearling industry in Broome and other coastal towns (Moore Citation1994).

Methodologically, we used a modified version of rank-clocks in contrast to the one introduced by Batty (Citation2006) as it was necessary to adapt the visualisation method to the purpose of this paper – understanding the evolution of settlement systems at edges. For instance, in this study, a city ranked as first was always at the circumference rather than at the centre of the rank-clock plot to better visualise trajectories of higher-ranked observations. Modifying rank-clocks this way visually emphasises the dominant role of one or a few large population centres as characteristic for edges (Huskey and Taylor Citation2016; Karácsonyi and Taylor Citation2023) and the lack of and delayed downward densification. Furthermore, rank-clocks were used here to visualise the evolution of settlement system from the commencement of records which means there was a growing number of ranked observations over the entire timeframe to represent the growing complexity of the settlement system.

It should be also stressed that rank-shifts are sometimes the result of technical and methodological issues (see ) that are, as observed by Huang et al. (Citation2015), usually neglected in rank-shift analyses. These include data limitations from undercounting for Indigenous populations, and the exclusion of temporary residents at different censuses such as Asian pearling labourers in northern coastal towns like in Broome during the first half of twentieth century (Lo Citation2010). The inclusion or exclusion of temporary residents could cause large swings in de-jure populations (usual resident population at census night) even in recent censuses and particularly for small settlements. Furthermore, census population data were not representative of the entire population before 1971 because of the exclusion of Indigenous Australians (Smith Citation1980). Additionally, the ‘frontier reality’ on the ground meant that census records for localities were random and sporadic, especially during earlier stages and particularly for the Northern Territory.

While these limitations are important to recognise, township-level population data presented here is the longest and most consistently available, capturing long-term hierarchic changes for the settlement system in Northern Australia. Analysis of long-term changes in ranking is worthwhile because rank-size positionalities at the time reflect the relative significance of the localities compared to others as service and population centres regardless of the difference between recorded census population and actual population numbers at the time. The rank-size approach helps to deviate from emphasising absolute population growth or decline and provides a systematic representation for understanding the evolution of each township as part of the whole settlement system and in relation to each other. In this respect, the census population count is used here to measure the relative importance of the locality only at the given time and the change is reflected by this changing relative importance over time, rather than by total population change as a ‘real’ process.

Hence, the study here can be considered as a quantitative analysis and measurement by sums of rank-shifts of the changing volatilities and turbulences within and a documentation of the evolution of the settlement system in Northern Australia. It is also a demonstration of the potential for policy, economic conditions and definitional peculiarities for inclusion and exclusion in population data to effect volatility in the recorded settlement populations and the broader system. This is valuable for understanding whether and why parts of the region might be ‘locked-in’ to particular development trajectories or how dependence on a staple industry or product can impact relative settlement growth as well as the entire settlement system (Barnes, Hayter, and Hay Citation2001).

Conclusions

Addressing the problem of intermitted population growth for urban centres and localities at sparsely populated remote edges is a target for policy making and workforce planning. Regional development policies are concerned with the sustainability of economic and demographic progression in these regions while academic and other literature often considers them as doomed or trapped by their remote and sparse environment (Carson et al. Citation2011; Huskey Citation2006; Productivity Commission Citation2017; Taylor et al. Citation2011). The focus of such policies are increasingly on the main population centre and on absolute population growth, while the remainder of settlements tend to be clustered as ‘the rest’ where little is understood about their diversity in trajectories and how the settlement system evolves and changes over time, such as changes in systemic synergies and regional cohesion. We have demonstrated that the application of the rank-clock method and the sums of rank-shifts measurement empirically supplements existing scholarship because rank-clocks document population progressions for individual settlements in a relativistic way while sums of rank-shifts quantify changing volatilities and synergies within the settlement system. In this sense, each settlement is seen in the context of all other settlements that existed at the time and changing positionalities in the settlement system are measured, compared to other timeframes to quantify long-term evolution in the system as a whole or for selected settlements. Additionally, our study and the applied methodology were not limited to resource towns only, enabling comparisons of the changing relative importance of settlements with diverse economic profiles and demographic compositions.

In summary, demonstrating the longitudinal relative dynamics of the Northern Australian settlement system has improved the understanding of instability in population numbers and intermittent demographic progression at edges. The study is replicable for other jurisdictions where long-term data are available and has revealed the turbulent history of boom and bust for resource towns, including impacts from no-town development. This systematic and relativistic understanding could form a basis for future differentiated policy approaches, where the problems of larger, stabilising centres and smaller, more volatile, diverse, economically disconnected and distant population concentrations are addressed differently, beyond considering their absolute sizes only.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- ABS. 2014. “Indigenous Status Standard.”

- AIATSIS. 2021. “Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (2021). The 1967 Referendum.”

- Altman, Jon. 2003. “People on Country, Healthy Landscapes and Sustainable Indigenous Economic Futures: The Arnhem Land Case.” The Drawing Board: An Australian Review of Public Affairs 4 (2): 65–82.

- Altman, Jon. 2009. “Indigenous Communities, Miners and the State in Australia.” In Power, Culture, Economy, edited by Jon Altman, and David Martin, 17–50. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Ash, Andrew, and Ian Watson. 2018. “Developing the North: Learning from the Past to Guide Future Plans and Policies.” The Rangeland Journal 40 (4): 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1071/RJ18034.

- Australian Government. 2016. “Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility Act 2016.”

- Barbier, Edward B. 2005. “Frontier Expansion and Economic Development.” Contemporary Economic Policy 23 (2): 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1093/cep/byi022.

- Barnes, Trevor J, Roger Hayter, and Elizabeth Hay. 2001. “Stormy Weather: Cyclones, Harold Innis, and Port Alberni, BC.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 33 (12): 2127–2147. https://doi.org/10.1068/a34187.

- Batty, Michael. 2006. “Rank Clocks.” Nature 444 (7119): 592–596. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05302.

- Batty, Michael. 2010. “Visualizing Space–Time Dynamics in Scaling Systems.” Complexity 16 (2): 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/cplx.20342.

- Batty, Michael. 2015. “Scale, Power Laws and Rank Size in Spatial Analysis.” In Geocomputation: A Practical Primer, edited by Chris Alex and Singleton Brunsdon, 40–60. London: SAGE.

- Bauer, F. H. 1964. Historical Geography of White Settlement in Part of Northern Australia. Part 2. The Katherine-Darwin Region: CSIRO. Canberra: Division of Land Research and Regional Survey.

- Blomley, Nicholas. 2003. “Law, Property, and the Geography of Violence: The Frontier, the Survey, and the Grid.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 93 (1): 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8306.93109.

- Bone, Robert. 1998. “Resource Towns in the Mackenzie Basin.” Cahiers de géographie du Québec 42 (116): 249–259. https://doi.org/10.7202/022739ar.

- Bradbury, John. 1984. “The Impact of Industrial Cycles in the Mining Sector: The Case of the Québec-Labrador Region in Canada.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 8 (3): 311–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.1984.tb00613.x.

- Bradbury, John H., and Isabelle St-Martin. 1983. “Winding Down in a Quebec Mining Town: A Case Study of Schefferville.” Canadian Geographies/Géographies canadiennes 27 (2): 128–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.1983.tb01468.x.

- Bylund, Erik. 1960. “Theoretical Considerations Regarding the Distribution of Settlement in Inner North Sweden.” Geografiska Annaler 42 (4): 225–231. https://doi.org/10.2307/520290.

- Carson, Dean. 2011. “Political Economy, Demography and Development in Australia’s Northern Territory.” Canadian Geographies/Géographies Canadiennes 55 (2): 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2010.00321.x.

- Carson, Doris Anna, Dean Bradley Carson, and Neil Argent. 2022. “Cities, Hinterlands and Disconnected Urban-Rural Development: Perspectives from Sparsely Populated Areas.” Journal of Rural Studies 93:104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.05.012.

- Carson, Dean, and Jen Cleary. 2010. “Virtual Realities: How Remote Dwelling Populations Become More Remote Over Time Despite Technological Improvements.” Sustainability 2 (5): 1282–1296. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2051282.

- Carson, Dean, Prescott C. Ensign, Rasmus Ole Rasmussen, and Andrew Taylor. 2011. “Perspectives on ‘Demography at the Edge’.” In Demography at the Edge. Remote Human Populations in Developed Nations, edited by Carson Dean, Prescott C. Ensign, Rasmus Ole Rasmussen, Huskey Lee, and Andrew Taylor, 3–20. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Dyrting, Sigurd, Andrew Taylor, and Fiona Shalley. 2020. “A Life-Stage Approach for Understanding Population Retention in Sparsely Populated Areas.” Journal of Rural Studies 80:439–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.10.021.

- Edmonds, Penelope. 2010. Urbanizing Frontiers: Indigenous Peoples and Settlers in 19th-Century Pacific Rim Cities. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Ferguson, James. 2005. “Seeing Like an Oil Company: Space, Security, and Global Capital in Neoliberal Africa.” American Anthropologist 107 (3): 377–382. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2005.107.3.377.

- Guo, Yongrui, Jie Zhang, and Honglei Zhang. 2016. “Rank–Size Distribution and Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Tourist Flows to China’s Cities.” Tourism Economics 22 (3): 451–465. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2014.0430.

- Halseth, Greg, Sean Markey, Laura Ryser, Neil Hanlon, and Mark Skinner. 2017. “Exploring New Development Pathways in a Remote Mining Town: The Case of Tumbler Ridge, BC, Canada.” Journal of Rural and Community Development 12 (2-3): 1–22.

- Halseth, Greg, and Lana Sullivan. 2004. “From Kitimat to Tumbler Ridge: A Crucial Lesson Not Learned in Resource-Town Planning.” Western Geography 13-14:132–160.

- Havlin, Shlomo. 1995. “The Distance Between Zipf Plots.” Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 216 (1): 148–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4371(95)00069-J.

- Hayter, Roger, Trevor J Barnes, and Michael J Bradshaw. 2003. “Relocating Resource Peripheries to the Core of Economic Geography’s Theorizing: Rationale and Agenda.” Area 35 (1): 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4762.00106.

- Hayter, Roger, and Stephan Nieweler. 2018. “The Local Planning-Economic Development Nexus in Transitioning Resourceindustry Towns: Reflections (Mainly) from British Columbia.” Journal of Rural Studies 60:82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.03.006.

- Holmes, John H., and Richard E. Lonsdale. 1981. Settlement Systems in Sparsely Populated Regions: The United States and Australia. New York: Pergamon Press.

- Houghton, D. S. 1993. “Long-distance Commuting: A new Approach to Mining in Australia.” The Geographical Journal 159 (3): 281–290. https://doi.org/10.2307/3451278.

- Huang, Qingxu, Chunyang He, Bin Gao, Yang Yang, Zhifeng Liu, Yuanyuan Zhao, and Yue Dou. 2015. “Detecting the 20 Year City-Size Dynamics in China with a Rank Clock Approach and DMSP/OLS Nighttime Data.” Landscape and Urban Planning 137:138–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.01.004.

- Huskey, Lee. 2006. “Limits to Growth: Remote Regions, Remote Institutions.” The Annals of Regional Science 40 (1): 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-005-0043-5.

- Huskey, Lee, and Andrew Taylor. 2016. “The Dynamic History of Government Settlements at the Edge.” In Settlements at the Edge: Remote Human Settlements in Developed Nations, edited by Carson Taylor Andrew, Dean B. Ensign, Prescott C. Huskey, Lee Rasmussen, Rasmus Ole, and Gertrude Saxinger, 25–48. Gloucester: Edward Elgar.

- Jackson, Tony, and Barbara Illsley. 2006. “Tumbler Ridge, British Columbia: The Mining Town That Refused to die.” Journal of Transatlantic Studies 4 (2): 163–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/14794010708656846.

- Jażdżewska, Iwona. 2017. “Spatial and Dynamic Aspects of the Rank-Size Rule Method. Case of an Urban Settlement in Poland.” Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 62:199–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2016.11.006.

- Karácsonyi, Dávid, and Andrew Taylor. 2023. “Understanding Demographic and Economic Patterns in Sparsely Populated Areas – a Global Typology Approach.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 105 (3): 228–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2022.2103445.

- Kauppila, Pekka. 2011. “Cores and Peripheries in a Northern Periphery: A Case Study in Finland.” Fennia – International Journal of Geography 189 (1): 20–31.

- Keeling, Arn and John Sandlos. 2017. “Ghost Towns and Zombie Mines: The Historical Dimensions of Mine Abandonment, Reclamation and Redevelopment in the Canadian North.” In Ice Blink: Navigating Northern Environmental History, edited by Stephen Bocking and Brad Martin, 377–420. University of Calgary Press.

- Kotey, Bernice, and John Rolfe. 2014. “Demographic and Economic Impact of Mining on Remote Communities in Australia.” Resources Policy 42:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2014.10.005.

- Langton, Marcia, and Odette Mazel. 2008. “Poverty in the Midst of Plenty: Aboriginal People, the ‘Resource Curse’ and Australia’s Mining Boom.” Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law 26 (1): 31–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646811.2008.11435177.

- Lawrie, Misty, Matthew Tonts, and Paul Plummer. 2011. “Boomtowns, Resource Dependence and Socio-Economic Well-Being.” Australian Geographer 42 (2): 139–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2011.569985.

- Le Tourneau, François-Michel. 2020. “Sparsely Populated Regions as a Specific Geographical Environment.” Journal of Rural Studies 75:70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.12.012.

- Le Tourneau, François-Michel. 2022. “‘It’s Not for Everybody’: Life in Arizona’s Sparsely Populated Areas.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 112 (6): 1794–1811. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2022.2035208.

- Linge, G. J. R. 1965. The Delimitation of Urban Boundaries for Statistical Purposes with Special Reference to Australia. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Lo, Jacqueline. 2010. “Burning Daylight: Staging Asian-Indigenous History in Northern Australia.” Amerasia Journal 36 (2): i–iv. https://doi.org/10.17953/amer.36.2.tu94128u311j7u38.

- Lucas, Rex A. 1971. Minetown, Milltown, Railtown: Life in Canadian Communities of Single Industry. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Marais, Lochner, Fiona Haslam McKenzie, Leith Deacon, Etienne Nel, Deidre van Rooyen, and Jan Cloete. 2018. “The Changing Nature of Mining Towns: Reflections from Australia, Canada and South Africa.” Land Use Policy 76:779–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.03.006.

- Markey, Sean, Greg Halseth, and Don Manson. 2008. “Challenging the Inevitability of Rural Decline: Advancing the Policy of Place in Northern British Columbia.” Journal of Rural Studies 24:409–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2008.03.012.

- McKenzie, Fiona Haslam. 2011. “Resource Boom Times: Building Towns and Cities in Remote Places.” 5th state of Australian cities national conference; 29 November–2 December 2011; Melbourne, Australia. ..APO-59976.

- Moore, Ronald. 1994. “The Management of the Western Australian Pearling Industry, 1860 to the 1930s.” The Great Circle: Journal of the Australian Association for Maritime History 16 (2): 121–138.

- O’Faircheallaigh, Ciaran. 2013. “Extractive Industries and Indigenous Peoples: A Changing Dynamic?” Journal of Rural Studies 30:20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.11.003.

- Paterson, Alistair. 2005. “Early Pastoral Landscapes and Culture Contact in Central Australia.” Historical Archaeology 39 (3): 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03376692.

- Porteous, J. D. 1970. “The Nature of the Company Town.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 51:127–142. https://doi.org/10.2307/621766.

- Pritchard, Bill. 2003. “Beyond the Resource Enclave: Regional Development Challenges in Resource Economies of Northern Remote Australia.” Australasian Journal of Regional Studies 9 (2): 137–150.

- Productivity Commission. 2017. Transitioning Regional Economies. Canberra: Australian Government.

- Prout, Sarah.. 2008. On the move? Indigenous temporary mobility practices in Australia. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research Working Paper 48. Canberra: ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences.

- Randall, James E., and R. Geoff Ironside. 1996. “Communities on the Edge: An Economic Geography of Resource-Dependent Communities in Canada.” Canadian Geographies/Géographies Canadiennes 40 (1): 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.1996.tb00430.x

- Robertson, Stuart, and Boyd Blackwell. 2015. “Remote Mining Towns on the Rangelands: Determining Dependency Within the Hinterland.” The Rangeland Journal 37 (6): 583–596. https://doi.org/10.1071/RJ15046.

- Scrimgeour, David. 2007. “Town or Country: Which is Best for Australia’s Indigenous Peoples?” Medical Journal of Australia 186 (10): 532–533. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01030.x.

- Smith, L. R. 1980. The Aboriginal Population of Australia. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

- Smith, Len, Rowse Tim, and Hungerford Stuart. 2019. Historical and Colonial Census Data Archive (HCCDA). ADA Dataverse. https://dataverse.ada.edu.au/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.26193/MP6WRS.

- Storey, Keith. 2001. “Fly-in/fly-out and fly-Over: Mining and Regional Development in Western Australia.” Australian Geographer 32 (2): 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049180120066616.

- Storey, Keith. 2010. “Fly-in/fly-out: Implications for Community Sustainability.” Sustainability 2:1161–1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2051161.

- Storey, Keith. 2023. “From FIFO to LILO: The Place Effects of Digitalization in the Mining Sector.” The Extractive Industries and Society 13:101206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2022.101206.

- Storey, Keith, and Heather Hall. 2018. “Dependence at a Distance: Labour Mobility and the Evolution of the Single Industry Town.” Canadian Geographies / Géographies Canadiennes 62 (2): 225–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12390.

- Sutton, Peter. 2001. “The Politics of Suffering: Indigenous Policy in Australia Since the 1970s.” Anthropological Forum 11 (2): 125–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664670125674.

- Taylor, Andrew. 2011. “Indigenous Demography: Convergence, Divergence, or Something Else?” In Demography at the Edge. Remote Human Populations in Developed Nations, edited by Ensign Carson Dean, Prescott C. Rasmussen, Rasmus Ole, Lee Huskey, and Andrew Taylor, 145–162. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Taylor, Andrew. 2012. “Information Communication Technologies and new Indigenous Mobilities? Insights from Remote Northern Territory Communities.” Journal of Rural and Community Development 7 (1): 59–73.

- Taylor, Andrew. 2016. “Introduction: Settlements at the Edge.” In Settlements at the Edge: Remote Human Settlements in Developed Nations, edited by Taylor Andrew; Dean B. Carson, Prescott C. Ensign, Lee Huskey, Rasmus Ole Rasmussen, and Gertrude Saxinger, 3–24. Gloucester: Edward Elgar.

- Taylor, Andrew, Silva Larson, Natalie Stoeckl, and Dean Carson. 2011. “The Haves and Have Nots in Australia’s Tropical North – New Perspectives on a Persisting Problem.” Geographical Research 49 (1): 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2010.00648.x.

- Taylor, Andrew, Hannah Payer, and Tony Barnes. 2018. “The Missing Mobile: Impacts from the Incarceration of Indigenous Australians from Remote Communities.” Applied Mobilities 3 (2): 150–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2017.1347027.

- Taylor, Andrew, James Thurmer, and David Karácsonyi. 2022. “Regional Demographic and Economic Challenges for Sustaining Growth in Northern Australia.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 9 (1): 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2022.2082316.

- Thurmer, James, and A. Taylor. 2021. “Internal Return Migration and the Northern Territory: New Migration Analysis for Understanding Population Prospects for Sparsely Populated Areas.” Population Research and Policy Review 40 (4): 795–817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-020-09616-5.

- Tonts, Matthew, Kristen Martinus, and P. Plummer. 2013. “Regional Development, Redistribution and the Extraction of Mineral Resources: The Western Australian Goldfields as a Resource Bank.” Applied Geography 45: 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2013.03.004.

- Tonts, Matthew, and Paul Plummer. 2012. “Natural Resource Exploitation and Regional Development: A View from the West.” Dialogue (Los Angeles, Calif 31 (1). Accessed June 24, 2024. https://socialsciences.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Dialogue-31-1-2012.pdf.

- Tonts, Matthew, Paul Plummer, and Misty Lawrie. 2012. “Socio-economic Wellbeing in Australian Mining Towns: A Comparative Analysis.” Journal of Rural Studies 28 (3): 288–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.10.006.

- Wilson, Lisa J. 2004. “Riding the Resource Roller Coaster: Understanding Socioeconomic Differences Between Mining Communities.” Rural Sociology 69 (2): 261–281. https://doi.org/10.1526/003601104323087606.

- Wilson, Tom. 2015. “The Demographic Constraints on Future Population Growth in Regional Australia.” Australian Geographer 46 (1): 91–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2014.986786.

- Wilson, Tom, and Taylor Andrew. 2016. “How Reliable Are Indigenous Population Projections?” Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues 19 (3): 39–57.

- Wolfskill, George, and Stanley Palmer. 1981. “Introduction.” In Essays on Frontiers in World History, edited by Palmer Wolfskill George, ix–xvi. Stanley Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Xu, Shuai, Yan Sun, and Shuqing Zhao. 2021. “Contemporary Urban Expansion in the First Fastest Growing Metropolitan Region of China: A Multicity Study in the Pearl River Delta Urban Agglomeration from 1980 to 2015.” Urban Science 5 (1): 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci5010011.

- Zipf, George Kingsley. 1949. Human Behavior and the Principle of Least Effort. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley Press.