ABSTRACT

Objective: A sense of belonging – the subjective feeling of deep connection with social groups, physical places, and individual and collective experiences – is a fundamental human need that predicts numerous mental, physical, social, economic, and behavioural outcomes. However, varying perspectives on how belonging should be conceptualised, assessed, and cultivated has hampered much-needed progress on this timely and important topic. To address these critical issues, we conducted a narrative review that summarizes existing perspectives on belonging, describes a new integrative framework for understanding and studying belonging, and identifies several key avenues for future research and practice.

Method: We searched relevant databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, PsycInfo, and ClinicalTrials.gov, for articles describing belonging, instruments for assessing belonging, and interventions for increasing belonging.

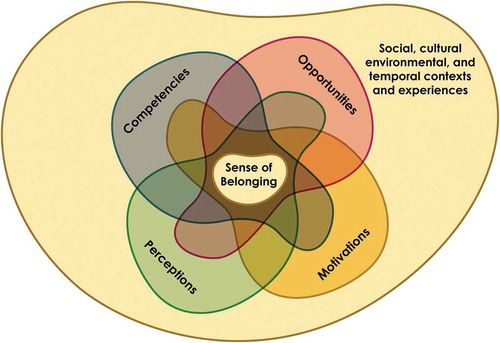

Results: By identifying the core components of belonging, we introduce a new integrative framework for understanding, assessing, and cultivating belonging that focuses on four interrelated components: competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions.

Conclusion: This integrative framework enhances our understanding of the basic nature and features of belonging, provides a foundation for future interdisciplinary research on belonging and belongingness, and highlights how a robust sense of belonging may be cultivated to improve human health and resilience for individuals and communities worldwide.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

Belonging is a fundamental human need that all people are driven to satisfy.

However, there is disagreement in the literature regarding how a person should go about increasing their sense of belonging.

There is also little consensus regarding how belonging should be conceptualized and measured.

What this topic adds:

The review article draws together disparate perspectives on belonging and harnesses the strengths of this multitude of perspectives to help advance the field.

The paper provides a framework that can help inform researchers, practitioners, and individuals seeking to increase a sense of belonging in themselves and in the organizations and groups in which they work and live.

We posit that competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions are central elements in strategies that can be used to increase our individual and collective sense of belonging for the betterment of society.

Although the importance of social relationships, cultural identity, and – especially for indigenous people – place have long been apparent in research across multiple disciplines (e.g., Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Cacioppo & Hawkley, Citation2003; Carter et al., Citation2018; Maslow, Citation1954; Rouchy, Citation2002; Vaillant, Citation2012), the year 2020 – with massive bushfires in Australia and elsewhere destroying ancient lands, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Black Lives Matter movement in the U.S., amongst other events – brought the importance of belonging to the forefront of public attention. Belonging can be defined as a subjective feeling that one is an integral part of their surrounding systems, including family, friends, school, work environments, communities, cultural groups, and physical places (Hagerty et al., Citation1992). Most people have a deep need to feel a sense of belonging, characterized as a positive but often fluid and ephemeral connection with other people, places, and/or experiences (Allen, Citation2020a).

There is general agreement that belonging is a fundamental human need that almost all people seek to satisfy (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Deci & Ryan, Citation2000; Leary & Kelly, Citation2009; Maslow, Citation1954). However, there is less agreement about the belonging construct itself, how belonging should be measured, and what people can do to satisfy the need for belonging. These issues have arisen in part because the belonging literature is broad and theoretically diverse, with authors approaching the topic from many different perspectives, with little integration across these perspectives. Therefore, there is a need to bring together disparate perspectives to better understand belonging as a construct, how it can be assessed, and how it can be developed. This narrative review describes several central issues in belonging research, bringing together various viewpoints on belonging and harnessing the strengths of the multitude of perspectives. Based on this review, we propose an integrative framework on belonging and consider implications of this framework for future research and practice.

Buried in biology

A need to belong – to connect deeply with other people and secure places, to align with one’s cultural and subcultural identities, and to feel like one is a part of the systems around them – appears to be buried deep inside our biology, all the way down to the human genome (Slavich & Cole, Citation2013). Physical safety and well-being are intimately linked with the quality of human relationships and the characteristics of the surrounding social world (Hanh, Citation2017), and connection with other people and places is crucial for survival (Boyd & Richerson, Citation2009). Indeed, for Indigenous people, “others” and “place” are synonymous and are inextricably entwined, where country provides a deep sense of belonging and identity as Aboriginal people (Harrison & McLean, Citation2017).

The so-called “need to belong” has been observed at both the neural and peripheral biological level (e.g., Blackhart et al., Citation2007; Kross et al., Citation2007; Slavich et al., Citation2014; Slavich, Way et al., Citation2010), as well as behaviourally and socially (e.g., Brewer, Citation2007; Filstad et al., Citation2019). Disparate lines of research suggest that the principal design of the human brain and immune system is to keep the body biologically and physically safe by motivating people to avoid social threats and seek out social safety, connection, and belonging (Slavich, Citation2020). Indeed, a sense of belonging may be just as important as food, shelter, and physical safety for promoting health and survival in the long run (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Maslow, Citation1954).

A dynamic, emergent construct

Although belonging occurs as a subjective feeling, it exists within a dynamic social milieu. Biological needs complement, accentuate, and interact with social structures, norms, contexts, and experiences (Slavich, Citation2020). Social, cultural, environmental, and geographical structures, broadly defined, provide an orientation for the self to determine who and what is acceptable, the nature of right and wrong, and a sense of belonging or alienation (Allen, Citation2020b). The sense of self emerges from one’s predominant social and environmental contexts, reinforcing and challenging the subjective sense of belonging. Belonging is facilitated and hindered by people, things, and experiences involving the social milieu, which dynamically interact with the individual’s character, experiences, culture, identity, and perceptions. Put another way, belonging exists “because of and in connection with the systems in which we reside” (Kern et al., Citation2020, p. 709).

Struggling to belong

Despite its importance, many people struggle to feel a sense of belonging. Socially, a significant portion of people suffer from social isolation, loneliness, and a lack of connection to others (Anderson & Thayer, Citation2018). For example, in 2017, in Australia, half of adults surveyed reported lacking companionship at least some of the time, and one in four adults could be classified as being lonely (Australian Psychological Society, Citation2018). Similar findings have been reported in the United States, where 63% of men and 58% of women reported feeling lonely (Cigna, Citation2018). Social disconnection has become a concerning trend across many developed cultures for several reasons, including social mobility, shifts in technology, broken family and community structures, and the pace of modern life (Baumeister & Robson, Citation2021). The COVID-19 pandemic magnified and accelerated the struggles that already existed. Early studies investigating the social and mental health impacts of the pandemic have pointed to increases in loneliness and mental illness, especially among vulnerable populations, that is caused at least in part from extended periods of isolation, social distancing, and rising distrust of others (Ahmed et al., Citation2020; Allen, Citation2020b; Dsouza et al., Citation2020; Gruber et al., Citationin press; Wang et al., Citation2020).

Struggles to belong are particularly evident in minorities and other groups that have been historically marginalised by mainstream cultures. For instance, even as many Indigenous people experience a sense of well-being when they connect with and participate in their traditional culture (e.g., Colquhoun & Dockery, Citation2012; Dockery, Citation2010; O’Leary, Citation2020), many Aboriginal people also experience ongoing grief from country dispossession (Williamson et al., Citation2020). As bushfires ravaged Australian lands early in 2020, for example, the grief of the fires for Indigenous Australians was significantly worse than nonIndigenous people, as they not only watched the fires decimate their land, but also their memories, sacred places, and the hearts of who they are as a people (Williamson et al., Citation2020). Several months later, the killing of George Floyd, a Black man in the U.S., initiated protests worldwide that provided a sense of meaning in connecting with others against racism (Ramsden, Citation2020), bringing to light yet again the systemic exclusion that Black people have long experienced in the U.S. and elsewhere (Corbould, Citation2020; Yulianto, Citation2020).

A narrative review of belonging research

With this background in mind, we narratively review existing studies on belonging, considering different perspectives on how belonging has been defined and operationalised, along with correlates, predictors, and outcomes associated with belonging. Although belonging is not merely the opposite of loneliness, social isolation, or feelings of disconnection, across the literature, low and high belonging have often been conceptualized as representing different sides of the same conceptual continuum (Allen & Kern, Citation2017, Citation2019; for a review of belonging and loneliness, see Lim et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, because of the shared similarities and close relationships between the constructs, we include studies that have considered the presence of belonging, low levels of belonging, and disconnection indicators.

Defining belonging

Definitions of the constructs of “belonginess” and “belonging” have lacked conceptual clarity and consistency across studies, which has limited advances in the science and practice of belonging. Belonging has been defined and operationalised in several ways (e.g., Goodenow, Citation1993; Hagerty & Patusky, Citation1995; Malone et al., Citation2012; Nichols & Webster, Citation2013), which has enabled investigators to test whether interventions increase a sense of belonging over days, weeks, or months. However, definitions have often explicitly focused on social belonging, thus missing other essential aspects such as connection to place and culture, and the dynamic interactions with the social milieu, as described above.

Additionally, because of the increased importance of belonging during adolescence, much of the research on belonging has involved students in school settings (Abdollahi et al., Citation2020; Arslan et al., Citation2020; Yeager et al., Citation2018). Definitions of belonging have tended to include school-based experiences, relationships with peers and teachers, and students’ emotional connection with or feelings toward their school (Allen & Bowles, Citation2012; Allen et al., Citation2018, Citation2016; O’Brien & Bowles, Citation2013; Slaten et al., Citation2016). Goodenow and Grady’s (Citation1993) definition remains the most commonly used definition: “the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school social environment” (p. 80).

A distinction can be made between trait (i.e., belonging as a core psychological need) and state (i.e., situation-specific senses of belonging) belongingness. Studies suggest that state belonging is influenced by various daily life events and stressors (Ma, Citation2003; Sedgwick & Rougeau, Citation2010; Walton & Cohen, Citation2011). Depending on the variability of situations and experiences that one encounters, along with one’s perceptions of those situations and experiences, a person’s subjective sense of belonging can change as frequently as several times a day, in much the same way that happiness and other emotions change over time (Trampe et al., Citation2015). However, people can also have relatively stable experiences of belonging. For example, some individuals demonstrate generally high or low levels of belonging with relatively little variability across time and different situations. In contrast, for others, a sense of belonging is more variable, depending on one’s awareness of and perceptions of environmental context and social cues (Schall et al., Citation2016). For instance, whereas one individual might perceive a smile from a coworker as a sign that they are part of a community, another person might suspect a contrived behaviour and see it as a sign of exclusion. Indeed, research suggests that the effects of belonging-related stressors can be more intense for those who identify with outgroups (Walton & Brady, Citation2017). Such outgroups include those from racial minorities, those who identify as sexually or gender diverse, or individuals with behaviours, attributes, or abilities that depart from the social norm, such as those that stem from mental health issues or disability (Gardner et al., Citation2019; Harrist & Bradley, Citation2002; Rainey et al., Citation2018; Spencer et al., Citation2016; Steger & Kashdan, Citation2009).

It appears that multiple processes must converge for a stable, trait-like sense of belonging to emerge and support well-being and other positive outcomes (Cacioppo et al., Citation2015; Erzen & Çikrikci, Citation2018; Mellor et al., Citation2008; Rico-Uribe et al., Citation2018; Walton & Cohen, Citation2011). For instance, a successful singer might be motivated to sing and have the skills and capacity needed to sing well, confidence, opportunities to sing, and support by others. It would seem that trait belongingness is more crucial for mental health and well-being; that is, a more stable and lasting sense of belonging as opposed to a state of belonging (i.e., a temporary feeling of belonging based on thoughts, feelings, and behaviours (Clark et al., Citation2003).

Assessing belonging

Several different instruments have been used to assess belonging but there is no consensus, gold-standard measure. The differentiation between state and trait belongingness has made defining and measuring belonging even more complicated. Most belonging measures are unidimensional, subjective, and static, representing a snapshot of a person’s perception at the time of administration. Instruments such as Walton’s measures of belonging and belonging uncertainty have been used in various studies within education and social psychology (Pyne et al., Citation2018; Walton & Cohen, Citation2007). These measures assess belonging from a more state-based sense of belonging, capturing transitory feelings of belonging or lack of situation-specific belonging (Walton, Citation2014; Walton & Brady, Citation2017). Other measures, such as the UCLA Loneliness Scale, potentially assess a more stable, trait-like sense of belonging, pointing to belonging as a core psychological need (Mahar et al., Citation2014). It could be argued that commonly used belonging measures are more accurate in assessing state-like experiences due to their propensity to assess belonging in a single snapshot (Cruwys et al., Citation2014; Leary et al., Citation2013; Martin, Citation2007). This is also the case with more applied belonging studies, such as those focused on school belonging (Allen et al., Citation2018; Arslan & Allen, Citation2020).

Given that no single measure of belonging exists, research has examined numerous belonging surveys to identify commonalities that can be applied across a variety of disciplines. Mahar et al. (Citation2014) reviewed several instruments for assessing belongingness and found that belonging was often measured as related to the performance indicators of specific types of service organisations. For example, the sense of belonging to a church congregation may depend on the amount of support a person receives from that congregation whereas belonging to a university is dependent not just on social connections but also on how well a student performs academically. As a whole, therefore, various social science disciplines have their own measures and scales for assessing belonging.

However, there are some commonalities in all of the studies reviewed by Mahar et al. (Citation2014). First, a sense of belonging is based on an individual’s perception of their connection to a chosen group or place. Most instruments that Mahar and colleagues reviewed contained at least one question that referenced the feeling of belonging, whether to a large group such as a country or race or a small group such as a church or school. Second, the sense of belonging is dependent on opportunities for interaction with others. Each survey reviewed referenced this variable differently, using words such as “relationships,” “making friends,” “spending time,” and “bonding.” Whatever term is used, the instruments all appear to be measuring the same thing – namely, the opportunities a person has to belong to a desired group.

A few scales specifically ask respondents to evaluate their motivations to connect and build relationships with a desired group. Motivations appear to be an area of importance that is often ignored in previous survey tools. The importance of this element will be further explored below.

In addition, several measures consider the ability to belong. Specifically, does the individual have the social skills and abilities it takes to belong to a group? The reviewed instruments might include a question such as “I find it easy to make friends” (Mahar et al., Citation2014, p. 23); however, the questions do not specifically address whether an individual is able to belong to the desired group because of their behaviours or attitudes.

Correlates, predictors, and outcomes associated with belonging

Regardless of how belonging has been defined and measured, the fundamental importance of belonging combined with elevated levels of social disconnection evident in modern society has led to several fruitful areas of research and application. A sense of belonging has been used as an independent, dependent, and correlated variable in a wide range of studies demonstrating the salience of this construct across various contexts (e.g., Allen et al., Citation2018; Freeman et al., Citation2007). For instance, Mahar et al. (Citation2014) reviewed how a sense of belonging was measured and acted as a service outcome among persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities, concluding that belonging is an important outcome in this domain. Other studies have found a positive association between students’ belonging needs and psychological well-being (Karaman & Tarim, Citation2018; Kitchen et al., Citation2015). Undergraduates’ involvement in courses that use technology was found to be related to higher belonging levels (Long, Citation2016). Additionally, a sense of belonging has been positively related to persistence in course study (Akiva et al., Citation2013; Hausman et al., Citation2007; Moallem, Citation2013). Across these and other studies, greater belonging has been consistently associated with more positive psychosocial outcomes.

Other studies have considered the implications of belonging interventions that target (a) characteristics of the individual including personality, social skills, and cognitions (e.g., Durlak et al., Citation2011; Frydenberg et al., Citation2004; Walton & Cohen, Citation2011); (b) their social relationships (e.g., Aron et al., Citation1997; Kanter et al., Citation2018); or (c) the environment that individuals inhabit, such as the physical attributes of the workplace, sense of space, and opportunities to connect (e.g., Gustafson, Citation2009; Jaitli & Hua, Citation2013; Trawalter et al., Citation2020). Most intervention studies have treated belonging as a secondary outcome rather than directly targeting belonging (Arslan et al., Citation2020), although there are some exceptions. For instance, in a brief social belonging intervention in a college setting for Black Americans, positive effects appeared to be long-lasting (i.e., from 7 to 11 years; Brady et al., Citation2020). A brief social belonging intervention among minority students had positive impacts on academic and health outcomes among minority students by encouraging students to understand that the feeling of not belonging is normal and temporary (Walton & Cohen, Citation2011). Additionally, Borman et al. (Citation2019) found that improvement in students’ sense of belonging partially mediated the effects of a similar intervention on academic achievement and disciplinary problems in secondary school.

Other research has examined the benefits that arise from a sense of belonging. These studies have identified numerous positive effects of having a healthy sense of belonging, including more positive social relationships, academic achievement, occupational success, and better physical and mental health (e.g., Allen et al., Citation2018; Goodenow & Grady, Citation1993; Hagerty et al., Citation1992). A lack of belonging, in turn, has been linked to an increased risk for mental and physical health problems (Cacioppo et al., Citation2015; Hari, Citation2019). Indeed, a meta-analysis of 70 studies concluded that the health risks associated with social isolation are equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day and is twice as harmful as obesity (Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2015). Likewise, studies have found that deficits in social relationships across the lifespan are associated with depression, poor sleep quality, rapid cognitive decline, cardiovascular difficulties, and reduced immunity (Hawkley & Capitanio, Citation2015). More specifically, the adverse effects of not belonging or being rejected include an increased risk for mental illness, antisocial behaviour, lowered immune functioning, physical illness, and early mortality (e.g., Cacioppo & Hawkley, Citation2003; Cacioppo et al., Citation2011; Choenarom et al., Citation2005; Cornwell & Waite, Citation2009; Holt-Lunstad, Citation2018; Leary, Citation1990; Slavich, O’Donovan et al., Citation2010).

An integrative framework for belonging

The take-home message from this review is that belonging is a central construct in human health, behaviour, and experience. However, studies on this topic have used inconsistent terminology, definitions, and measures. At times, belonging has been treated as a predictor, outcome, correlate, and covariate. Moreover, it is unclear whether the lack of a sense of belonging is equivalent to negative constructs such as loneliness, disconnection, and isolation, or if these are separate dimensions. These inconsistencies have arisen in part from the multiple theoretical and empirical perspectives present in the belonging literature. Building on these different perspectives and insights, we propose an integrative framework to conceptualise belonging measures and inform future research, practice, and interventions. More specifically, we suggest that belonging is a dynamic feeling and experience that emerges from four interrelated components that arise from and are supported by the systems in which individuals reside. As illustrated in , the four components are:

competencies for belonging (skills and abilities);

opportunities to belong (enablers, removal/reduction of barriers);

motivations to belong (inner drive); and

perceptions of belonging (cognitions, attributions, and feedback mechanisms – positive or negative experiences when connecting).

Figure 1. An integrative framework for understanding, assessing, and fostering belonging. Four interrelated components (i.e., Competencies, Opportunities, Motivations, and Perceptions) dynamically interact and influence one another, shifting, evolving, and adapting as an individual traverses temporal, social, and environmental contexts and experiences

As a dynamic social system, these four components reinforce and influence one another over time, as a person moves through different social, environmental, and temporal contexts and experiences. Together they dynamically interact with, are supported or hindered by, and impact relevant social milieus. The narrative of how these components interconnect results in consistently high belonging levels, which support positive life outcomes.

Competencies for belonging

The first component we suggest belonging emerges from is competencies: having a set of skills and abilities (both subjective and objective) needed to connect and experience belonging. Skills enable individuals to relate with others, identify with their cultural background, develop a sense of identity, and connect to place and country. Competencies enable people to ensure that their behaviour is consistent with group social norms, align with cultural values, and treat the place and land with respect. The development of social competencies is central to social and emotional learning approaches [e.g., Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL), Citation2018], and plays a critical role in supporting positive youth development (Durlak et al., Citation2011; Kern et al., Citation2017). In turn, deficits in social competencies can limit relationship quality, social relations, and social positions (Frostad & Pijl, Citation2007).

With some exceptions, most people can develop skills to improve their ability to connect with people, things, and places. Social skills include being aware of oneself and others, emotion and behavioural regulation, verbal and nonverbal communication, acknowledgement and alignment with social norms, and active listening (Blackhart et al., Citation2011). Cultural skills include understanding one’s heritage, mindful acknowledgement of place, and alignment with relevant values. Social, emotional, and cultural competencies complement and reinforce one another, and contribute to and are reinforced by feeling a sense of belonging. The ability to regulate emotions, for example, may reduce the likelihood of social rejection or ostracisation from others (Harrist & Bradley, Citation2002). Competencies can also help individuals cope effectively with feelings of not belonging when they arise (Frydenberg et al., Citation2009). Pointing to the social nature of competencies, the display and use of skills may be socially reinforced through acceptance and inclusion. In turn, feeling a sense of belonging may also assist in using socially appropriate skills (Blackhart et al., Citation2011).

Opportunities to belong

The second component we suggest belonging emerges from is opportunities: the availability of groups, people, places, times, and spaces that enable belonging to occur. The ability to connect with others is useless if opportunities to connect are lacking. For instance, studies with people from rural or isolated areas, first- and second-generation migrants, and refugees have found that these groups have more difficulty managing psychological well-being, physical health, and transitions (Correa-Velez et al., Citation2010; Keyes & Kane, Citation2004). They might have social competencies, but their circumstances limit opportunities to foster belonging. For example, Correa-Velez et al. (Citation2010) studied nearly 100 adolescent refugees who had been in Melbourne, Australia, for three years or less. Even with deliberate steps taken to help the students integrate into their new schools, including language development, they overwhelmingly reported feelings of discrimination and bullying, and subsequently exhibited a lower sense of well-being. Although these students had the skills to connect with their schoolmates, they were not given opportunities to connect. Similarly, legacies of racism, dispossession, and assimilation have continued to exclude Aboriginal people from connecting with and managing their homelands (Williamson et al., Citation2020).

The need for opportunities became poignantly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, as social distancing was enforced in countries around the world and many human interactions became virtual in nature. Active membership of extracurricular groups, schools, universities, workplaces, church groups, families, friendship groups, and participation in hobbies provide opportunities for human connections. For instance, school attendance is a prerequisite for students to feel a sense of belonging with their school (Akar-Vural et al., Citation2013; Bowles & Scull, Citation2019). In the absence of physical opportunities for belonging, technologies such as social media and online gaming may help meet this need, especially for youth (Allen et al., Citation2014; Davis, Citation2012) and for those who are introverted, shy, or who suffer from social anxiety (Amichai-Hamburger et al., Citation2002; Moore & McElroy, Citation2012; Ryan et al., Citation2017; Seabrook et al., Citation2016; Seidman, Citation2013). However, it remains uncertain the extent to which technologically mediated approaches can fully compensate for face-to-face interactions.

The Black Lives Matter movement particularly points to opportunities for those that are often excluded by building social capital that strengthens connections, allows activists to share their messages, and illuminates the inequities existing within and across cultures. In Putnam’s (Citation2000) work on social capital identified social networks as fundamental principles for creating opportunity. Putnam described the concepts of bridging and bonding social capital, in which the former was later referred to as inclusive belonging, whereas the latter pertains to exclusive belonging (Putnam, Citation2000; Roffey, Citation2013). Bonding social capital highlights the connections found within a community of people sharing similar characteristics or backgrounds, including interests, attitudes, and demographics (Claridge, Citation2018). This might be observed with close friends and family members (Claridge, Citation2018) or other homogenous groups such as a church based women’s reading group or an over-50s mens’ basketball team (Putnam, Citation2000). In contrast, bridging social capital is inclusive because it creates broader social networks and a higher degree of social reciprocity between members (Putnam, Citation2000). Bridging social capital may emerge from the connection people build to share their resources (Murray et al., Citation2020). Most members are interconnected through this type of social capital, which transcends class, race, religion, and sociodemographic characteristics. Bridging social capital occurs when there is an opportunity for any person to interact with others (Putnam, Citation2000). This might look like a sporting event, a gathering of concerned about a common concern like climate change or racism, or even attendance at a public concert. In the same way, inclusive belonging represents mutual benefits for all parties involved. In contrast, exclusive belonging presents the idea that a selected group will benefit from membership, particularly those who are members of the group (Roffey, Citation2013). Communities and organisations can employ inclusive belonging principles that may improve the experience of belonging for people, particularly vulnerable to rejection and prone to social isolation and loneliness (Allen et al., Citation2019; Roffey, Citation2013; Roffey et al., Citation2019).

There are numerous ways for individuals, groups, and communities to create opportunities for belonging, and some of these opportunities can even be motivated by a sense of not belonging (Leary & Allen, Citation2011; London et al., Citation2007). For example, those who have been disenfranchised, have suffered abuse or trauma, or have been ostracised or rejected may look for alternative sources for belonging (Gerber & Wheeler, Citation2009; Hagerty et al., Citation2002). This search for belonging outside, or in opposition to, established norms provides one explanation for the rise of radicalisation and extremism (Leary et al., Citation2006; Lyons-Padilla et al., Citation2015), participation in gangs and organised crime (Voisin et al., Citation2014), and school violence (Leary et al., Citation2003). It can also be an incentive for more socially acceptable pathways to belonging, such as through joining support groups, or bonding together with diverse others to fight against racism (Ramsden, Citation2020). At individual, institutional, and societal levels, there is a need to create opportunities and reduce barriers to enable positive connection to occur so that people are less likely to seek out problematic contexts for belonging.

Motivations to belong

The third component we suggest belonging emerges from is motivations: a need or desire to connect with others. Belonging motivation refers to the fundamental need for people to be accepted, belong, and seek social interactions and connections (Leary & Kelly, Citation2009). Socially, a person who is motivated to belong is someone who enjoys positive interactions with others, seeks out interpersonal connections, has positive experiences of long-term relationships, dislikes negative social experiences, and resists the loss of attachments (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). In social situations, people who are motivated to belong will actively seek similarities and things in common with others. Similarly, a person might be motivated to connect with a place, their culture or ethnic background, or other belonging contributors.

The degree to which people are motivated to belong varies, although this characteristic is not always accounted for by personality type or attributes (Leary & Kelly, Citation2009). Weak motivation to belong can be associated with psychological dysfunction (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995), and weak motivation may, alongside other socially mediated criteria, become a predictor of psychological pathology (Leary & Kelly, Citation2009). A lack of motivation may arise in part from repeated rejection and thwarting of one’s basic psychological needs of relatedness, competence, and autonomy (Ryan & Deci, Citation2001), resulting in a learned helplessness response (Nelson et al., Citation2019) that manifests as a reduced motivation to belong. Nevertheless, Baumeister and Leary (Citation1995) suggest that people can still be driven and motivated to connect with others, even under the most traumatic circumstances.

Hence, individual differences and context play central roles in our understanding of belonging motivation. The range of possible motivators for belonging are vast and will reflect diverse sociocultural and economic environments such as indigenous-non-indigenous, collectivist-individualist, urban-rural, developed-developing. It is essential that any examination of the nature and function of motivators of belonging acknowledges this diversity and includes it in any conceptualisation of this construct.

Perceptions of belonging

The fourth component we suggest belonging emerges from is perceptions: a person’s subjective feelings and cognitions concerning their experiences. A person may have skills related to connecting, opportunities to belong, and be motivated, yet still report great dissatisfaction. Either consciously or subconsciously, most human beings evaluate whether they belong or fit in with those around them (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Walton & Brady, Citation2017).

Perceptions about one’s experiences, self-confidence, and desire for connection can be informed by past experiences (Coie, Citation2004). For example, a person with a history of rejection or ostracization might question their belonging or seek to belong through other means (London et al., Citation2007). This seeking could involve groups that are considered to be antisocial, such as cults, street or criminal gangs or group memberships characterised by radicalised social, political or religious ideas (Hunter, Citation1998). This might involve returning to one’s home or place of origin or trying to find one’s place within a world that has systemically erased their value. A rejected student may engage in maladaptive behaviours in a classroom to seek approval from peers (Flowerday & Shaughnessy, Citation2005). Indeed, in one study, indigenous children reported underperforming at school so that they would not be ostracised from their group (McInerney, Citation1989). In other words, maintaining belonging with their indigenous peers was more salient than doing well at school; doing well at school was a white thing (Herbert et al., Citation2014; McInerney, Citation1989). It was also apparent that perceptions of themselves as successful students (i.e., a feeling of belongingness at school) were weak for many Indigenous students but for “adaptive” reasons. Repeated social rejection experiences can create the perception (by both the individual and others who witness the repeated social rejection) that the person is not socially acceptable (Walton & Cohen, Citation2007). Negative perceptions of the self or others, stereotypes, and attribution errors can also undermine motivation (Mello et al., Citation2012; Walton & Wilson, Citation2018; Yeager & Walton, Citation2011). These subjective experiences and perceptions of those experiences thus act as feedback mechanisms that increase or decrease one’s desire to connect with others.

Just as the need to belong can shape emotions and cognitions (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Lambert et al., Citation2013), cognitions and emotions also impact a person’s capacities, opportunities, and motivations for belonging. To address these links and help enhance belonging, a variety of psychosocial interventions grounded in cognitive therapy aim to (a) reframe cognitions concerning negative social interactions and experiences, (b) normalise feelings of not belonging that everyone experiences from time to time, and (c) alter the extent to which the events that caused the feeling are internal vs. external to the individual (e.g., Walton & Cohen, Citation2007). These interventions have been shown to change not just cognitions about other people and the world (Borman et al., Citation2019; Butler et al., Citation2006) but also basic biological processes involved in the immune system that are known to affect human health and behaviour (Black & Slavich, Citation2016; Shields et al., Citation2020).

Implications for research and practice

As we have alluded to, belonging research has been the subject of decades of development and broad multidisciplinary input and insights. As a result of this history, though, perspectives on this topic are highly diverse, as are the methods used for assessing this construct. Strategies for enhancing a sense of belonging exist, but identifying effective solutions depends on integrating multiple disciplinary approaches to theory, research, and practice, rather than relying on the silos of single disciplines. Arising from the framework described above, we highlight six main challenges and issues related to understanding, measuring, and building belonging below, and identify several topics that would benefit from additional attention and research.

First, belonging research has occurred within multiple disciplines but has been primarily siloed into separate domains. Understanding and support for belonging is a subject of concern in many fields, including psychology (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995), sociology (May, Citation2011), education (Morieson et al., Citation2013), urban education (Riley, Citation2017), medicine (Cacioppo & Hawkley, Citation2003), public health (Stead et al., Citation2011), economics (Bhalla & Lapeyre, Citation1997), design (Schein, Citation2009; Trudeau, Citation2006; Weare, Citation2010), and political science (Yuval-Davis, Citation2006). However, little work has integrated across these disciplines, with differing terms, measures, and approaches used, yielding a fractured and inconsistent perspective on belonging. Thus, there is a need for authentic attempts to synthesise these findings fully and integrate, develop, and extend belonging research through genuinely interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches (Choi & Pak, Citation2006). Our integrative framework provides an initial attempt at bringing these different perspectives together, but the extent to which it is sufficient and applicable within different disciplines remains to be seen.

Second, there is a need for belonging researchers to develop a more robust understanding of the existing literature. The theoretical, methodological, and conceptual gaps need to be bridged to make this literature much more widely accessible. Knowledge development in this area will lead to improved research measurement and practitioner tools, potentially based on multitheoretical, empirically driven perspectives that will, in turn, make the bridging of future theory, research, practice, and lived application easier for all stakeholders. Our framework provides an initial organising structure to map out the literature, identify gaps, and support further knowledge development in the future. Numerous theories across disciplines contribute to each of the components, and future work could identify how different theories map onto, intersect with, and inform understanding, assessment, and enhancement of belonging.

Third, there are significant gaps between research and practice in the context of belonging. One important factor contributing to this gap is the sheer breadth and complexity of belonging research. Thus, researchers in this field make conscious – and conscientious – efforts to collaborate and translate their work to and for other researchers and practitioners. We suggest that our framework provides an accessible entry point into the relevant research for practitioners. The four components highlight specific areas to focus interventions, identifying enablers and barriers of each of the components. Building belonging begins with a need to ensure that communities have a foundational understanding of the importance of belonging for psychological and physical health and that individuals can draw on and advance their competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions to increase their sense of belonging. Still, there is a need to identify specific strategies within each component that can help people develop and harness their competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions across different situations, experiences, and interactions.

Fourth, consideration needs to be given to how belonging is best measured. Existing instruments for assessing belonging primarily focus on social belonging, rather than on the broader, more inclusive construct of a sense of belonging as a whole. It is unclear whether positive and negative aspects of belonging are unidimensional or multidimensional. For instance, positive affect is not merely the absence of negative affect. Positive cognitive biases are different from low levels of negative cognitive bias, and disengagement is not necessarily the same as low engagement levels. Belonging and loneliness tend to be inversely correlated (Mellor et al., Citation2008), but the extent to which this is true across different individuals, contexts, and measures is unknown.

Existing measures also generally provide a state-like assessment of a person’s sense of belonging (i.e., at a given point in time). However, as a dynamic emergent construct, measuring and targeting singular (or even multiple) components in a fixed manner is insufficient. Studies will benefit from examining the best way to capture and track dynamic patterns and identifying (a) when and how a sense of belonging emerges from competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions; (b) the contextual factors needed to enable this emergence to occur; and (c) the feedback mechanisms that reinforce or block the emergence of belonging in a person.

Fifth, although we suggested that four components are necessary for belonging to emerge, it is unknown how much of each of these components is needed, whether specific sequencing amongst the components matters (i.e., one needs to come before the other), and the extent to which that depends upon the person and the context. For example, culture can intensely affect an individual’s competencies for belonging, opportunities to belong, motivations to belong, and even perceptions of belonging (Cortina et al., Citation2017). As a dynamic, emergent construct, each component likely impacts upon and interacts with the others. Still, for some individuals or across different contexts, there might be specific sequences that are more likely to support a sense of belonging. Aligned with other psychological and sociological studies, the existing belonging literature has primarily used variable-centred approaches. Person-centred research that has been conducted points to belonging as being a nonlinear construct, with the ability for the sense of belonging to grow, stall, disappear, or flourish within an individual over the life course (George & Selimos, Citation2019). Longitudinal, person-centred approaches might be a useful complement to traditional study designs because they allow the opportunity to track experiences of belonging in diverse populations, identify the combination of the four components described above, and when belonging emerges, with consideration of personal, social, and environmental moderators.

Finally, multilevel research is needed to elucidate social, neural, immunologic, and behavioural processes associated with belonging. This integrative research can help researchers understand how experiences of belonging “get under the skin” to affect human behaviour and health. Equally important is the need to understand the biological processes that are affected by experiences of disconnection versus belonging, which can help researchers elucidate the regulatory logic of these systems to understand better what aspects of belonging are most critical or essential for health (Slavich, Citation2020; Slavich & Irwin, Citation2014). Such knowledge can ultimately help investigators develop more effective interventions for increasing perceptions of belonging and lead to entirely new ways of conceptualising this fundamental construct.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a sense of belonging is a core part of what makes us human (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Deci & Ryan, Citation2000; Slavich, Citation2020; Vaillant, Citation2012). Just as harbouring a healthy sense of belonging can lead to many positive life outcomes, feeling as though one does not belong is robustly associated with a lack of meaning and purpose, increased risk for experiencing mental and physical health problems, and reduced longevity. As technology continues to develop, the pace of modern life has sped up, traditional social structures have broken down, and cultural and ethnic values have been threatened, increasing the importance of helping people establish and sustain a fundamental sense of belonging. Focusing on competencies, opportunities, motivations, and perceptions can be a useful framework for developing strategies aimed at increasing peoples’ sense of belonging at both the individual and collective level. To fully realize this framework’s potential to aid society, though, much work is needed.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with regard to this work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdollahi, A., Panahipour, S., Tafti, M. A., & Allen, K. A. (2020). Academic hardiness as a mediator for the relationship between school belonging and academic stress. Psychology in the Schools, 57(5), 823–832. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22339

- Ahmed, M. Z., Ahmed, O., Aibao, Z., Hanbin, S., Siyu, L., & Ahmad, A. (2020). Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092

- Akar-Vural, R., Yilmaz-Özelçi, S., Çengel, M., & Gömleksiz, M. (2013). The development of the “Sense of Belonging to School” scale. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 53, 215–230.

- Akiva, T., Cortina, K. S., Eccles, J. S., & Smith, C. (2013). Youth belonging and cognitive engagement in organized activities: A large-scale field study. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34(5), 208–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2013.05.001

- Allen, K. A. (2020a). Psychology of belonging. Routledge.

- Allen, K. A. (2020b). Commentary: A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in youth mental health. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 959. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00959

- Allen, K. A., & Bowles, T. (2012). Belonging as a guiding principle in the education of adolescents. Australian Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology, 12, 108–119.

- Allen, K. A., Boyle, C., & Roffey, S. (2019). Creating a culture of belonging in a school context. Educational and Child Psychology, 36(4), 5–7.

- Allen, K. A., & Kern, M. L. (2017). School belonging in adolescents: Theory, research, and practice. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5996-4

- Allen, K. A., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

- Allen, K. A., & Kern, P. (2019). Boosting school belonging in adolescents: Interventions for teachers and mental health professionals. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203729632

- Allen, K. A., Ryan, T., Gray, D. L., McInerney, D., & Waters, L. (2014). Social media use and social connectedness in adolescents: The positives and the potential pitfalls. The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 31(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2014.2

- Allen, K. A., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2016). Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.5

- Amichai-Hamburger, Y., Wainapel, G., & Fox, S. (2002). On the Internet no one knows I’m an introvert: Extroversion, neuroticism, and Internet interaction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 5(2), 125–128. https://doi.org/10.1089/109493102753770507

- Anderson, G. O., & Thayer, C. (2018, September). Loneliness and social connections: A national survey of adults 45 and older. https://www.aarp.org/research/topics/life/info-2018/loneliness-social-connections.html

- Aron, A., Melinat, E., Aron, E. N., Vallone, R. D., & Bator, R. J. (1997). The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness: A procedure and some preliminary findings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(4), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297234003

- Arslan, G., & Allen, K. A. (2020). School bullying, mental health, and wellbeing in adolescents: Mediating impact of positive psychological orientations. Child Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09780-2

- Arslan, G., Allen, K. A., & Ryan, T. (2020). Exploring the impacts of school belonging on youth wellbeing and mental health: A longitudinal study. Child Indicators Research, 13(5), 1619–1635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09721-z

- Australian Psychological Society. (2018). Australian loneliness report. https://psychweek.org.au/2018-archive/loneliness-study/

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Baumeister, R. F., & Robson, D. A. (2021). Belongingness and the modern schoolchild: On loneliness, socioemotional health, self-esteem, evolutionary mismatch, online sociality, and the numbness of rejection. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1877573

- Bhalla, A., & Lapeyre, F. (1997). Social exclusion: Towards an analytical and operational framework. Development and Change, 28(3), 413–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00049

- Black, D. S., & Slavich, G. M. (2016). Mindfulness meditation and the immune system: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1373, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12998

- Blackhart, G. C., Eckel, L. A., & Tice, D. M. (2007). Salivary cortisol in response to acute social rejection and acceptance by peers. Biological Psychology, 75(3), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.03.005

- Blackhart, G. C., Nelson, B. C., Winter, A., & Rockney, A. (2011). Self-control in relation to feelings of belonging and acceptance. Self and Identity, 10(2), 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298861003696410

- Borman, G. D., Rozek, C. S., Pyne, J. R., & Hanselman, P. (2019). Reappraising academic and social adversity improves middle-school students’ academic achievement, behavior, and well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(33), 16286–16291. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820317116

- Bowles, T., & Scull, J. (2019). The centrality of Cconnectedness: A conceptual synthesis of attending, belonging, engaging and flowing. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 29(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2018.13

- Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (2009). Culture and the evolution of human cooperation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1533), 3281–3288. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0134

- Brady, S. T., Cohen, G. L., Shoshana, N. J., & Walton, G. M. (2020). A brief social-belonging intervention in college improves adult outcomes for Black Americans. Science Advances, 6(18), eaay3689. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay3689

- Brewer, M. B. (2007). The importance of being we: Human nature and intergroup relations. American Psychologist, 62(8), 728–738. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.728

- Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2003). Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46(3), S39–S52. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2003.0049

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Norman, G. J., & Berntson, G. G. (2011). Social isolation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1231(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06028.x

- Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspectives in Psychological Science, 10(2), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615570616

- Carter, J., Hollinsworth, D., Raciti, M., & Gilbey, K. (2018). Academic ‘place-making’: Fostering attachment, belonging and identity for Indigenous students in Australian universities. Teaching in Higher Education, 23(2), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1379485

- Choenarom, C., Williams, R. A., & Hagerty, B. M. (2005). The role of sense of belonging and social support on stress and depression in individuals with depression. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 19(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2004.11.003

- Choi, B. C., & Pak, A. W. (2006). Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clinical and Investigative Medicine, 29(6), 351–364.

- Cigna. (2018). Cigna U.S. loneliness index: Survey of 20,000 Americans behaviors driving loneliness in the United States. Cigna/Ipsos National Report. https://www.cigna.com/static/www-cigna-com/docs/about-us/newsroom/studies-and-reports/combatting-loneliness/loneliness-survey-2018-full-report.pdf

- Claridge, T. (2018). Functions of social capital—Bonding, bridging, linking. Social Capital Research.

- Clark, L. A., Vittengl, J., Kraft, D., & Jarrett, R. B. (2003). Separate personality traits from states to predict depression. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(2), 152–172. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.17.2.152.23990

- Coie, J. D. (2004). The impact of negative social experiences on the development of antisocial behavior. In J. B. Kupersmidt & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), Decade of behavior. Children’s peer relations: From development to intervention (pp. 243–267). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10653-013

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2018). The collaborative for academic, social, and emotional learning. CASEL. https://casel.org/

- Colquhoun, S., & Dockery, A. M. (2012). The link between Indigenous culture and wellbeing: Qualitative evidence for Australian Aboriginal peoples. The Centre for Labour Market Research (1329–2676). http://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/2012.01_LSIC_qualitative_CLMR1.pdf

- Corbould, C. (2020, June). The fury in US cities is rooted in a long history of racist policing, violence and inequality. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-fury-in-us-cities-is-rooted-in-a-long-history-of-racist-policing-violence-and-inequality-139752

- Cornwell, E. Y., & Waite, L. J. (2009). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650905000103

- Correa-Velez, I., Gifford, S. M., & Barnett, A. G. (2010). Longing to belong: Social inclusion and well-being among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne, Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 71(8), 1399–1408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.018

- Cortina, K. S., Arel, S., & Smith-Darden, J. P. (2017, November). School belonging in different cultures: The effects of individualism and power distance. Frontiers in Education, 2, 56. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2017.00056

- Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A., Dingle, G. A., Haslam, C., & Jetten, J. (2014). Depression and social identity: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(3), 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314523839

- Davis, K. (2012). Friendship 2.0: Adolescents’ experiences of belonging and self-disclosure online. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1527–1536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.013

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Dockery, A. M. (2010). Culture and wellbeing: The case of Indigenous Australians. Social Indicators Research, 99(2), 315–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9582-y

- Dsouza, D. D., Quadros, S., Hyderabadwala, Z. J., & Mamun, M. A. (2020). Aggregated COVID-19 suicide incidences in India: Fear of COVID-19 infection is the prominent causative factor. Psychiatry Research, 290, e113145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113145

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

- Erzen, E., & Çikrikci, Ö. (2018). The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 64(5), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764018776349

- Filstad, C., Traavik, L. E., & Gorli, M. (2019). Belonging at work: The experiences, representations and meanings of belonging. Journal of Workplace Learning, 31(2), 116–142. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.monash.edu.au/10.1108/JWL-06-2018-0081

- Flowerday, T., & Shaughnessy, M. (2005). An interview with Dennis McInerney. Educational Psychology Review, 17(1), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-005-1637-2.

- Freeman, T. M., Anderman, L. H., & Jensen, J. M. (2007). Sense of belonging in college freshmen at the classroom and campus levels. The Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.3.203-220

- Frostad, P., & Pijl, S. J. (2007). Does being friendly help in making friends? The relation between the social position and social skills of pupils with special needs in mainstream education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 22(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250601082224

- Frydenberg, E., Care, E., Freeman, E., & Chan, E. (2009). Interrelationships between coping, school connectedness and well-being. Australian Journal of Education, 53(3), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494410905300305

- Frydenberg, F., Lewis, R., Bugalski, K., Cotta, A., McCarthy, C., Luscombe‐Smith, N., & Poole, C. (2004). Prevention is better than cure: Coping skills training for adolescents at school. Educational Psychology in Practice, 20(2), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360410001691053

- Gardner, A., Filia, K., Killacky, E., & Cotton, S. (2019). The social inclusion of young people with serious mental illness: A narrative review of the literature and suggested future directions. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 53(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867418804065

- George, G., & Selimos, E. D. (2019). Searching for belonging and confronting exclusion: A person-centred approach to immigrant settlement experiences in Canada. Social Identities, 25(2), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2017.1381834

- Gerber, J., & Wheeler, L. (2009). On being rejected: A meta-analysis of experimental research on rejection. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(5), 468–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01158.x

- Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1%3C79::AID-PITS2310300113%3E3.0.CO;2-X

- Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831

- Gruber, J., Prinstein, M. J., Clark, L. A., Rottenberg, J., Abramowitz, J. S., Albano, A. M., Aldao, A., Borelli, J. L., Chung, T., Davila, J., Forbes, E. E., Gee, D. G., Hall, G. C. N., Hallion, L. S., Hinshaw, S. P., Hofmann, S. G., Hollon, S. D., Joormann, J., Kazdin, A. E., Klein, D. N., ... Weinstock, L. M. (in press). Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000707

- Gustafson, P. (2009). Mobility and territorial belonging. Environment and Behavior, 41(4), 490–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508314478

- Hagerty, B. M., Lynch-Sauer, J. L., Patusky, K., Bouwsema, M., & Collier, P. (1992). Sense of belonging: A vital mental health concept. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 6(3), 172–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9417(92)90028-h

- Hagerty, B. M., & Patusky, K. (1995). Developing a measure of sense of belonging. Nursing Research, 44(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199501000-00003

- Hagerty, B. M., Williams, R. A., & Oe, H. (2002). Childhood antecedents of adult sense of belonging. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(7), 793–801. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.2007

- Hanh, T. N. (2017). The art of living: Peace and freedom in the here and now. Harper Collins.

- Hari, J. (2019). Lost connections: Uncovering the real causes of depression—and the unexpected solutions. Permanente Journal, 23, 18–231. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/18-231

- Harrison, N., & McLean, R. (2017). Getting yourself out of the way: Aboriginal people listening and belonging in the city. Geographical Research, 55(4), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12238

- Harrist, A. W., & Bradley, K. D. (2002). Social exclusion in the classroom: Teachers and students as agents of change. In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement (pp. 363–383). Academic Press.

- Hausman, L. R. M., Schofield, J. W., & Woods, R. L. (2007). Sense of belonging as a predictor of intentions to persist among African American and White first-year college students. Research in Higher Education, 48(7), 803–839. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25704530

- Hawkley, L. C., & Capitanio, J. P. (2015). Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: A lifespan approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1669), 20140114. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0114

- Herbert, J., McInerney, D. M., Fasoli, L., Stephenson, P., & Ford, L. (2014). Indigenous secondary education in the Northern Territory: Building for the future. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 43(2), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie2014.17

- Holt-Lunstad, J. (2018). Why social relationships are important for physical health: A systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

- Hunter, E. (1998). Adolescent attraction to cults. Adolescence, 33(131), 709–714.

- Jaitli, R., & Hua, Y. (2013). Measuring sense of belonging among employees working at a corporate campus: Implication for workplace planning and management. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 15(2), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRE-04-2012-0005

- Kanter, J. W., Kuczynski, A. M., Tsai, M., & Kohlenberg, R. J. (2018). A brief contextual behavioral intervention to improve relationships: A randomized trial. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 10, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.09.001

- Karaman, Ö., & Tarim, B. (2018). Investigation of the correlation between belonging needs of students attending university and well-being. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(4), 781–788. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2018.060422

- Kern, M. L., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Romer, D. (2017). The positive perspective on youth development. In D. Romer & The Commission Chairs of the Adolescent Mental Health Initiative of the Annenberg Public Policy Center and the Sunnylands Trust (Eds.), Treating and preventing adolescent mental disorders: What we know and what we don’t know (Vol. 2, pp. 543–567). Oxford University Press.

- Kern, M. L., Williams, P., Spong, C., Colla, R., Sharma, K., Downie, A., Taylor, J. A., Sharp, S., Siokou, C., & Oades, L. G. (2020). Systems informed positive psychology. Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(4), 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1639799

- Keyes, E. F., & Kane, C. F. (2004). Belonging and adapting: Mental health of Bosnian refugees living in the United States. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 25(8), 809–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840490506392

- Kitchen, P., Williams, A. M., & Gallina, M. (2015). Sense of belonging to local community in small-to-medium sized Canadian urban areas: A comparison of immigrant and Canadian-born residents. BMC Psychology, 3(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-015-0085-0

- Kross, E., Egner, T., Ochsner, K., Hirsch, J., & Downey, G. (2007). Neural dynamics of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(6), 945–956. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2007.19.6.945

- Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213499186

- Leary, M. R. (1990). Responses to social exclusion: Social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.221

- Leary, M. R., & Allen, A. B. (2011). Belonging motivation: Establishing, maintaining, and repairing relational value. In D. Dunning (Ed.), Frontiers of social psychology. Social motivation (pp. 37–55). Psychology Press.

- Leary, M. R., & Kelly, K. M. (2009). Belonging motivation. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 400–409). Guilford Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-12071–027

- Leary, M. R., Kelly, K. M., Cottrell, C. A., & Schreindorfer, L. S. (2013). Construct validity of the need to belong scale: Mapping the nomological network. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95(6), 610–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.819511

- Leary, M. R., Kowalski, R. M., Smith, L., & Phillips, S. (2003). Teasing, rejection, and violence: Case studies of the school shootings. Aggressive Behavior, 29(3), 202–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10061

- Leary, M. R., Twenge, J. M., & Quinlivan, E. (2006). Interpersonal rejection as a determinant of anger and aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_2

- Lim, M., Allen, K. A., Craig, H., Smith, D., & Furlong, M. J. (2021). Feeling lonely and a need to belong: What is shared and distinct? Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1883411

- London, B., Downey, G., Bonica, C., & Paltin, I. (2007). Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17(3), 481–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00531.x

- Long, L. L. (2016). How undergraduate’s involvement affects sense of belonging in courses that use technology. In Proceedings from 2016 American Society of Engineering Education (ASEE) Annual Conference and Exposition. https://doi.org/10.18260/p.25491

- Lyons-Padilla, S., Gelfand, M. J., Mirahmadi, H., Farooq, M., & van Egmond, M. (2015). Belonging nowhere: Marginalization & radicalization risk among Muslim immigrants. Behavioral Science & Policy, 1(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1353/bsp.2015.0019

- Ma, X. (2003). Sense of belonging to school: Can schools make a difference? The Journal of Educational Research, 96(6), 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670309596617

- Mahar, A. L., Cobigo, V., & Stuart, H. (2014). Comments on measuring belonging as a service outcome. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 20(2), 20–33.

- Malone, G. P., Pillow, D. R., & Osman, A. (2012). The general belongingness scale (G.B.S.): Assessing achieved belongingness. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.027

- Martin, A. (2007). The motivation and engagement scale (M.E.S.). Lifelong Achievement Group.

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harper and Row.

- May, V. (2011). Self, belonging and social change. Sociology, 45(3), 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511399624

- McInerney, D. M. (1989). Urban Aboriginals parents’ views on education: A comparative analysis. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 10(2), 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.1989.9963353

- Mello, Z. R., Mallett, R. K., Andretta, J. R., & Worrell, F. C. (2012). Stereotype threat and school belonging in adolescents from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds. Journal of At-Risk Issues, 17(1), 9–14.

- Mellor, D., Stokes, M., Firth, L., Hayashi, Y., & Cummins, R. (2008). Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(3), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.020

- Moallem, I. (2013). A meta-analysis of school belonging and academic success and persistence [Doctoral Dissertation]. Loyola University Chicago. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/726

- Moore, K., & McElroy, J. C. (2012). The influence of personality on Facebook usage, wall postings, and regret. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(1), 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.09.009

- Morieson, L., Carlin, D., Clarke, B., Lukas, K., & Wilson, R. (2013). Belonging in education: Lessons from the Belonging Project. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 4(2), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v4i2.173

- Murray, B., Domina, T., Petts, A., Renzulli, L., & Boylan, R. (2020). “We’re in this together”: Bridging and bonding social capital in elementary school PTOs. American Educational Research Journal, 57(5), 2210–2244. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831220908848

- Nelson, C. A., III, Zeanah, C. H., & Fox, N. A. (2019). How early experience shapes human development: The case of psychosocial deprivation. Neural Plasticity, 2019, 1676285. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1676285

- Nichols, A. L., & Webster, G. D. (2013). The single-item need to belong scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(2), 189–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.02.018

- O’Brien, K. A., & Bowles, T. V. (2013). The importance of belonging for adolescents in aecondary achool aettings. The European Journal of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 5(2), 977–985. http://dx.doi.org/10.15405%2Fejsbs.72

- O’Leary, C. (2020). An examination of Indigenous Australians who are flourishing [Master’s thesis]. The University of Melbourne.

- Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster.

- Pyne, J., Rozek, C. S., & Borman, G. D. (2018). Assessing malleable social-psychological academic attitudes in early adolescence. Journal of School Psychology, 71, 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.10.004

- Rainey, K., Dancy, M., Mickelson, R., Stearns, E., & Moller, S. (2018). Race and gender differences in how sense of belonging influences decisions to major in STEM. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0115-6

- Ramsden, P. (2020, June). How the pandemic changed social media and George Floyd’s death created a collective conscience. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/how-the-pandemic-changed-social-media-and-george-floyds-death-created-a-collective-conscience-140104

- Rico-Uribe, L. A., Caballero, F. F., Martín-María, N., Cabello, M., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., & Miret, M. (2018). Association of loneliness with all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. PloS One, 13(1), e0190033. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190033

- Riley, K. (2017). Place, belonging and school leadership: Researching to make the difference. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Roffey, S. (2013). Inclusive and exclusive belonging -the impact on individual and community well-being. Educational and Child Psychology, 30(1), 38–49.

- Roffey, S., Boyle, C., & Allen, K. A. (2019). School belonging — Why are our students longing to belong to school? Educational and Child Psychology, 36(2), 6–8.

- Rouchy, J. C. (2002). Cultural identity and groups of belonging. Group, 26(3), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021009126881

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

- Ryan, T., Allen, K. A., Gray, D. L., & McInerney, D. M. (2017). How social are social media? A review of online social behaviour and connectedness. Journal of Relationship Research, 8, E8. https://doi.org/10.1017/jrr.2017.13

- Schall, J., LeBaron Wallace, T., & Chhuon, V. (2016). ‘Fitting in’ in high school: How adolescent belonging is influenced by locus of control beliefs. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 21(4), 462–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2013.866148

- Schein, R. H. (2009). Belonging through land/scape. Environment and Planning A, 41(4), 811–826. https://doi.org/10.1068/a41125

- Seabrook, E. M., Kern, M. L., & Rickard, R. (2016). Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review. JMIR Mental Health, 3(4), e50. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5842

- Sedgwick, M. G., & Rougeau, J. (2010). Points of tension: A qualitative descriptive study of significant events that influence undergraduate nursing students’ sense of belonging. Rural and Remote Health, 10, 1569. https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/1569

- Seidman, G. (2013). Self-presentation and belonging on Facebook: How personality influences social media use and motivations. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(3), 402–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.10.009

- Shields, G. S., Spahr, C. M., & Slavich, G. M. (2020). Psychosocial interventions and immune system function: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(9), 1031–1043. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0431

- Slaten, C. D., Ferguson, J. K., Allen, K. A., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2016). School belonging: A review of the history, current trends, and future directions. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.6

- Slavich, G. M. (2020). Social safety theory: A biologically based evolutionary perspective on life stress, health, and behavior. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 16, 265–295. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045159

- Slavich, G. M., & Cole, S. W. (2013). The emerging field of human social genomics. Clinical Psychological Science, 1(3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613478594

- Slavich, G. M., & Irwin, M. R. (2014). From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: A social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 774–815. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035302