ABSTRACT

Scholars and social commentators have noted the escalating rates of loneliness among global societies for more than a decade. The need to quarantine, self-isolate, and physically distance during the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the way we interacted with each other – exacerbating feelings of loneliness. A sense of belonging and loneliness are sometimes used interchangeably and the research on their shared and distinct aspects is limited. One shared demographic vulnerability in the belonging and loneliness research is the focus on adolescents and young adults. This paper brings together research on the association between the two constructs as a way to explore the utility of belonging-focused perspectives and approaches for addressing loneliness at multiple socio-ecological levels. A proposed conceptual Dual Continuum Model of Belonging and Loneliness presents a multifaceted categorisation of the conjoint loneliness and belonging relationship. This paper highlights the role of belonging in addressing loneliness, which has critical implications for ongoing research and intervention.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

(1) Loneliness is considered to arise from a universal human need to belong.

(2) Loneliness and belonging are important constructs for social wellbeing.

(3) A sense of belonging and loneliness are terms that are often used interchangeably.

What this topic adds:

(1) The loneliness and belonging research have similarities but are also distinct.

(2) Loneliness and belonging could be conceptualised within a dual continuum model.

(3) The proposed dual model demonstrates that there is much more to understand about these constructs—theoretically, conceptually and empirically.

KEYWORDS:

The recent COVID-19 health crisis emphasises the importance of social relationships for people to not just live but to thrive and flourish. People have been asked to quarantine, self-isolate, and physically distance to curb rising infection rates (Smith & Lim, Citation2020). These necessary public health practices have led to changes in the way people interact with family, friends, colleagues, and neighbours. A consequence of these practices has led to increased attention on loneliness and social isolation. Loneliness is a term describing a subjective feeling of social isolation that arises when there is a difference between actual and desired relationships (Peplau & Perlman, Citation1982) and differs from objective indicators of social isolation (e.g., degree of contact with others or living alone). Loneliness is posited to arise from a human need to belong (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995). Belonging is defined more broadly in the literature, in that it can relate to belonging to a place or an experience (Allen, Citation2020); and the belonging subtype that is likely to be relevant to loneliness is social belonging. Belonging and loneliness are related constructs in that both are subjective states and part of normal human experience (Mellor et al., Citation2008).

One of the current challenges in the field is to decipher the conceptual relationship between loneliness and belonging. Specifically, what are their shared and distinct aspects? For example, what shared mechanisms drive a lower sense of belonging and higher levels of loneliness? Does a lower sense of belonging always lead to higher loneliness? Can one feel a lack of belonging and loneliness simultaneously? This paper highlights areas in which the loneliness and belonging scientific literature overlap and disentangles these constructs where possible.

Research investigating belonging and loneliness suggests that the two constructs are similar in that they refer to varying degrees of social connectedness (Russell, Citation1996; Mellor et al., Citation2008). In other words, loneliness and belonging may represent opposite ends of a continuum. In a study of belonging, connectedness, and social exclusion, however, Crisp (Citation2010) argues that social inclusion and exclusion may not be dualistic. Instead, he proposed that an individual can experience inclusion and exclusion simultaneously (Crisp, Citation2010). In other words, while belonging and loneliness may fall along a continuum, it is also possible to experience one of them and not the other. When an individual’s need for belonging is unmet, evidence suggests that this can lead to loneliness. Conversely, when an individual’s need for belonging is met, it is associated with decreased loneliness (Theeke et al., Citation2015). What seems to be the critical factor in the relationship between belonging and loneliness is not the sense of belonging per se, but the individual differences in the need to belong (Mellor et al., Citation2008). In the Australian Unity Wellbeing project, 436 adults (244 females and 192 males) participated in a study that examined the relationships between the need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction (Mellor et al., Citation2008). Results indicated that individual perceptions of connectedness to others were similar in both loneliness and belongingness. Research is relatively scant and mixed concerning evidence of the correlation between need to belong and loneliness. Leary et al. (Citation2013) reported a nonsignificant correlation, using the Need To Belong Scale (NTBS) and the University of California Los Angeles – Loneliness Scale (UCLA-LS; Russell, Citation1996). On the other hand, in a study of 869 US undergraduate university students, the NTBS correlated with loneliness (r = .44), after controlling for the variance shared with the Sense of Belonging Instrument–Antecedents (SOBI-A; Pillow et al., Citation2015). So, in this case, students who exhibited a higher need to belong were also experiencing higher levels of loneliness.

Demographic vulnerability

In early adolescence and young adulthood, the prevalence rates of loneliness ranged from 11-20% (Bartels et al., Citation2008) and 20-71%, respectively (Brennan, Citation1982; Hawthorne, Citation2008; Rönkä et al., Citation2014). A recent epidemiological cohort study reported that young adults experiencing high levels of loneliness were more likely to have experience bullying, social isolation, and mental health problems as children (Matthews et al., Citation2018). Qualter et al. (Citation2015) identified specific belonging needs and loneliness sources for individuals throughout the lifespan. Early adolescents aged 12 to 15 years were proposed to develop a sense of belonging through feeling accepted by their peers. In contrast, late adolescents to young adults (aged 15 to 21 years) developed a sense of belonging through experiencing validation from a friend, romantic relationships, peer-acceptance, or marital status (Qualter et al., Citation2015).

While belonging is a lifespan construct, there is extensive research on school belonging in children and adolescents. Several definitions of school belonging have also used interchangeable terms (e.g., school connectedness; Lester et al., Citation2013; McNeely et al., Citation2002), school identification (Voelkl, Citation1995), and school community (Osterman, Citation2000). Goodenow and Grady (Citation1993) provided the most widely used operationalised definition of the sense of school belonging, “the extent to which they [students] feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others – especially teachers and other adults in the school social environment” (p. 60). A qualitative meta-synthesis of student’s perspectives on school belonging highlighted the importance of student’s “feeling safe and secure in schools” (Goodenow & Grady, Citation1993, p. 1422) and peer-to-peer relationships (Craggs & Kelly, Citation2018). Other research has also emphasised the importance of the student-teacher relationship (Allen et al., Citation2018).

The literature describes several psychological theories concerning school belonging. These include the Belongingness hypothesis (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995), Bowlby’s attachment theory (Bowlby, Citation1973) and self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). A socio-ecological framework (Allen et al., Citation2016) of school belonging based on Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) sociological model of human development has also been proposed. Previous studies have reported a relationship between school belonging and loneliness. A study of 1,342 adolescents examined the agreement and discrepancy between the need to belong and relationship satisfaction with outcomes of depression, loneliness, and self-esteem (Verhagen et al., Citation2018). The study reported a relationship between a high need to belong and low relationship satisfaction – it was this discrepancy that was important. When relationship satisfaction was low, a high need to belong was associated with lower self-esteem, higher loneliness, and more depressive symptoms. Conversely, higher relationship satisfaction was related to higher self-esteem and lower loneliness, and lower depressive symptoms even when belongingness need was low. Another study (Rönkä et al., Citation2017) in which school liking (belonging) was defined by positive peer relationships, peer acceptance and peer support reported that for the girls only, higher school dislike was associated with higher loneliness. It may be possible that a focus on belonging, whether that be school belonging or general belonging may offer solutions to addressing loneliness in youth (Allen, Citation2020).

Measurement of belonging and loneliness

One barrier to better understanding the relationship between school belonging and loneliness relates to lack of consensus on how these constructs should be operationalized. Belonging at school has been defined, described, and measured in various ways (Allen & Kern, Citation2017; O’Brien & Bowles, Citation2013). Renshaw (Citation2018) and Renshaw and Bolognino (Citation2016) examined the impact of school connectedness on wellbeing as measured by the College Student Subjective Wellbeing Questionnaire (CSSWQ). Psychometrics of the CSSWQ showed that the questionnaire had good structural and convergent validity (Renshaw, Citation2018). In the development of the CSSWQ, items of the hypothesised School Connectedness Scale (UCS) were taken from the Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale (PSSM) (Renshaw & Bolognino, Citation2016) one of the most widely used measures of school belonging (Allen & Bowles, Citation2012; Allen et al., Citation2018). The scale serves as a measure of connectedness, which has comparable item structure and content items worded positively in the UCLA Loneliness Scale Revised (Renshaw & Bolognino, Citation2016). When considering the validity of informant ratings of loneliness, a study by Luhmann et al. (Citation2016) found convergent self- and informant ratings of loneliness in 463 young adults and their partners, friends and romantic partners – providing support for informant ratings of loneliness as valid indicators of this subjective internal state. Loneliness is generally analysed as a unidimensional construct, but psychometrically-validated instruments also identify subtypes of the loneliness experiences such as social loneliness and emotional loneliness (De Jong Gierveld & Kamphuls, Citation1985). Within a shorter version of the UCLA scale, subscales pertaining to intimate, relational, and collective connectedness have also been identified (Hawkley et al., Citation2005). Some of these subscales may be more related to belonging than others.

Using a positive psychology approach to address belonging and loneliness

One approach that has been used to provide a lens for understanding the relationship between school belonging and loneliness is that of positive psychology (Allen et al., Citation2020). Matthews et al. (Citation2018) suggested interventions that aim to reduce loneliness should focus on children or adolescents who experience bullying or social isolation from their peers. Some interventions may aim to increase social contact between students but may not necessarily alleviate loneliness, as loneliness tends to relate more to the quality of social contacts, rather than the quantity (Matthews et al., Citation2018). A meta-analysis on interventions targeting loneliness reported the most appropriate intervention were those aimed at addressing individual’s maladaptive social cognitions (Masi et al. (Citation2011). Since this review, positive psychology interventions, have been increasingly used to target loneliness in young people. In pilot evaluations, positive psychology interventions, show a potential to reduce loneliness in young people aged 18 to 25, with (Lim et al., Citation2020; Lim, Gleeson et al., Citation2020) and without a mental health disorder (Lim et al., Citation2019). Similarly, in school belonging interventions, Diebel et al. (Citation2016) examined the impact of a gratitude diary intervention on belonging in 100 students aged 7 to 11 years old. The gratitude diary intervention involved students writing in a diary daily over four weeks about what they were either grateful or thankful for in school. A control group wrote about school events that occurred on a specific day. The results showed that students who engaged with the gratitude diary intervention experienced improved school belonging and gratitude compared with the control group (Diebel et al., Citation2016).

Conceptualising the relationship between belonging and loneliness using a dual continuum approach

So how do belonging and loneliness relate to each other? Do they represent polar opposites as far as social functioning is concerned or might they be related in some other manner? The dual factor system or the dual continuum model of psychological functioning (Greenspoon & Saklofske, Citation2001) offers perspectives on how seemingly opposite parameters of psychological health are interrelated and work in concert to produce more nuanced outcomes. Within this model, mental health and mental illness, rather than representing opposite ends of a continuum, are viewed as independent but related constructs that co-exist with each other to predict overall psychological functioning. Thus, what has been called complete mental health is defined by low levels of psychological distress and high degrees of subjective well-being. At the other extreme, individuals defined as troubled evidence many distress symptoms in concert with low levels of overall well-being. A third group of individuals is considered to be psychologically vulnerable; they experience a few distress symptoms but a limited sense of well-being. A final group conceptualised as symptomatic but content experience high levels of distress but also report experience high well-being levels.

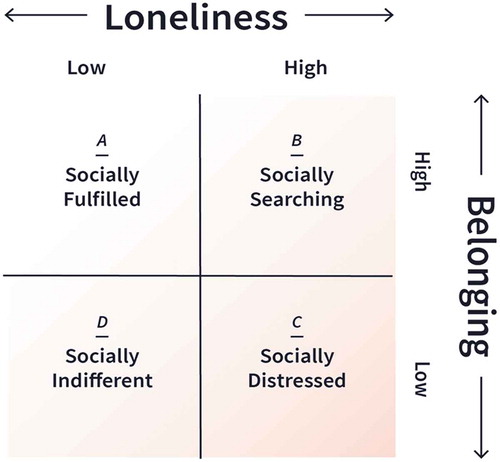

The multifaceted relationship between belonging and loneliness can be conceptualised in a manner similar to bidimensional mental health models (e.g., Keyes, Citation2002; Kim et al., Citation2014; Suldo & Shaffer, Citation2008). We propose that belonging and loneliness co-exist along a continuum, with four distinct groups of individuals categorised as high or low on the two constructs of interest. Reconceptualising how we view the relationship between belonging and loneliness using a Dual Continuum Model of Belonging and Loneliness may offer solutions to how we address loneliness in individuals, groups, and societies. Addressing loneliness through the establishment of meaningful social relationships is critical for our well-being. This conceptual model proposes an alternative perspective on loneliness and belonging. Rather than viewing the two constructs as opposite ends of a continuum, it may be that loneliness and belonging are independent, yet related constructs, with each making significant contributions to explain the complexity of our social needs. By viewing loneliness and belonging across the four quadrants shown in .

Figure 1. Dual Continuum Model of Belonging and Loneliness

The socially fulfilled group, as defined above, rarely experience feelings of loneliness and generally feel as if they belong, perhaps across multiple contexts. A second group also experience a sense of belonging but, at the same time, are lonely much of the time. We term this group as socially searching. It seems plausible that this group might experience belongingness in some contexts, such as work or family, but not in others (e.g., with intimate partners). A third group is comprised of individuals who lack a sense of belonging and, at the same time, experience high levels of loneliness. These individuals can be labelled as socially distressed. The final group, socially indifferent, do not feel as if they belong but are not particularly distressed (lonely) about it. They may even enjoy the sense of being-my-own-person and living more or less independently.

The model illustrates the complexity of peoples’ social needs – specifically, it is nuanced when conceptualise in two continua, belonging and loneliness, and considers how they occur independently in varying degrees. This conceptual model deserves further consideration because it can provide a useful framework for specific treatment recommendations. The implications of conceptualising belonging and loneliness in this way open doors for future research and evaluation that may have significant implications for how we respond to and address the complexity of social needs. Solutions can be formal or informal and administered by different levels if one considers a socio-ecological framework (i.e., the individual, within their relationships, or their community; Lim, Penn et al., Citation2020). Remaining questions include, what types of solutions, both formal and informal, do we need to remain socially fulfilled? In the same vein, what types of solutions can we offer to assist those who are socially distressed? Do those who are socially indifferent require our attention? Do those who are socially searching require specific attention in their one-on-one relationships with others?

Conclusion

We offered a novel perspective on how the constructs of belonging and loneliness may align, extending research in this area and presenting current understandings in a way that may be more practically relevant and publicly useful. Loneliness is recognised as a critical social issue of our time; nonetheless, it is plausible that the closely related construct social belonging provides an expanded strategy to address loneliness at the individual, relationships, and community levels. The research presented in the current paper highlights how the two constructs interconnected, and the Dual Continuum Model of Belonging and Loneliness may guide further research. The proposed model demonstrates that there is much more to understand about these constructs – theoretically, conceptually and empirically. Notably, it provides a nuanced approach to addressing loneliness by considering the interactive effects of sense of belonging.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Allen, K. A. (2020). The psychology of belonging (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Allen, K. A. (2020). Commentary of Lim, M., Eres, R., Gleeson, J., Long, K., Penn, D., & Rodebaugh, T. (2019). A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in youth mental health. Frontiers in Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00959

- Allen, K. A., & Bowles, T. (2012). Belonging as a guiding principle in the education of adolescents. Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 12, 108–119. ISSN 1446-5442. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1002251

- Allen, K. A., & Kern, M. L. (2017). School belonging in adolescents: Theory, research and practice. Springer.

- Allen, K. A., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

- Allen, K. A., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2016). Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.5

- Bartels, M., Cacioppo, J. T., Hudziak, J. J., & Boomsma, D. I. (2008). Genetic and environmental contributions to stability in loneliness throughout childhood. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 147B(3), 385–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.b.30608

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Separation: Anxiety and anger (2nd ed.). Basic Books.

- Brennan, T. (1982). Loneliness at adolescence. In L. A. Peplau & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 269–290). John Wiley & Sons.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Craggs, H., & Kelly, C. (2018). Adolescents’ experiences of school belonging: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(10), 1411–1425. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1477125

- Crisp, B. R. (2010). Belonging, connectedness and social exclusion. Journal of Social Inclusion, 1(2), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.36251/josi.14

- de Jong Gierveld, J., & Kamphuls, F. (1985). The development of a Rasch-Type loneliness scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 9(3), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662168500900307

- Diebel, T., Woodcock, C., Cooper, C., & Brignell, C. (2016). Establishing the effectiveness of a gratitude diary intervention on children’s sense of school belonging. Educational and Child Psychology, 33(2), 1–31.

- Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831

- Greenspoon, P. J., & Saklofske, D. H. (2001). Toward an integration of subjective well-being and psychopathology. Social Indicators Research, 54(1), 81–108. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007219227883

- Hawkley, L. C., Browne, M. W., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2005). How can I connect with thee? Let me count the ways. Psychological Science, 16(10), 798–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01617.x

- Hawthorne, G. (2008). Perceived social isolation in a community sample: Its prevalence and correlates with aspects of peoples’ lives. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(2), 140–150. https//doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0279-8

- Keyes, C. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

- Kim, E., Dowdy, E., & Furlong, M. (2014). An exploration of using a dual-factor model in school-based mental health screening. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 29(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573514529567

- Leary, M. R., Kelly, K. M., Cottrell, C. A., & Schreindorfer, L. S. (2013). Construct validity of the need to belong scale: Mapping the nomological network. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95(6), 610–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.819511

- Lester, L., Waters, S., & Cross, D. (2013). The Relationship between school connectedness and mental health during the transition to secondary school: A path analysis. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 23(2), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2013.20

- Lim, Eres, R., & Vasan, S. (2020). Understanding loneliness in the twenty-first century: An update on correlates, risk factors, and potential solutions. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(7), 793–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01889-7

- Lim, M. H., Gleeson, J. F. M., Rodebaugh, T. L., Eres, R., Long, K. M., Casey, K., Abbott, J. A. M., Thomas, N., & Penn, D. L. (2020). A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in young people with psychosis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(7), 877–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01681-2

- Lim, M. H., Penn, D. L., Thomas, N., & Gleeson, J. F. M. (2020). Is loneliness a feasible treatment target in psychosis? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(7), 901–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01731-9

- Lim, M. H., Rodebaugh, T. L., Eres, R., Long, K. M., Penn, D. L., & Gleeson, J. F. M. (2019). A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in youth mental health. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 604. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00604

- Luhmann, M., Bohn, J., Holtmann, J., Koch, T., & Eid, M. (2016). I’m lonely, can’t you tell? Convergent validity of self-and informant ratings of loneliness. Journal of Research in Personality, 61, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.02.002

- Masi, C. M., Chen, H. Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 219–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377394

- Matthews, T., Danese, A., Caspi, A., Fisher, H. L., Goldman-Mellor, S., Kepa, A., Moffitt, T. E., Odgers, C. L., & Arseneault, L. (2018). Lonely young adults in modern Britain: Findings from an epidemiological cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 49(2), 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718000788

- McNeely, C. A., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Promoting school connectedness: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of School Health, 72(4), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06533.x/

- Mellor, D., Stokes, M., Firth, L., Hayashi, Y., & Cummins, R. (2008). Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(3), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.020

- O’Brien, K. A., & Bowles, T. V. (2013). The importance of belonging for adolescents in secondary school settings. The European Journal of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 5(2), 976. https://doi.org/10.15405/ejsbs.72

- Osterman, K. F. (2000). Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 323–367. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070003323

- Peplau, L., & Perlman, D. (1982). Perspectives on loneliness. In L. Peplau & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 1–20). John Wiley and Sons.

- Pillow, D. R., Malone, G. P., & Hale, W. J. (2015). The need to belong and its association with fully satisfying relationships: A tale of two measures. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 259–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.031

- Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., Maes, M., & Verhagen, M. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615568999

- Renshaw, & Bolognino. (2016). The college student subjective wellbeing questionnaire: A brief, multidimensional measure of undergraduate’s covitality. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 17(2), 463–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9606-4

- Renshaw, T. L. (2018). Psychometrics of the revised college student subjective wellbeing questionnaire. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 33(2), 136–149. https//doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9606-4

- Rönkä, A. R., Rautio, A., Koiranen, M., Sunnari, V., & Taanila, A. (2014). Experience of loneliness among adolescent girls and boys: Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986 study. Journal of Youth Studies, 17(2), 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.805876

- Rönkä, A. R., Sunnari, V., Rautio, A., Koiranen, M., & Taanila, A. (2017). Associations between school liking, loneliness and social relations among adolescents: Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986 study. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2015.1136659

- Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and wellbeing. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Smith, B., & Lim, M. (2020). How the COVID-19 pandemic is focusing attention on loneliness and social isolation. Public Health Research & Practice. https://www.phrp.com.au/issues/june-2020-volume-30-issue-2/how-the-covid-19-pandemic-is-focusing-attention-on-loneliness-and-social-isolation/

- Suldo, S. M., & Shaffer, E. J. (2008). Looking beyond psychopathology: The dual-factor model of mental health in youth. School Psychology Review, 37(1), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2008.12087908

- Theeke, L. A., Mallow, J., Gianni, C., Legg, K., & Glass, C. (2015). The experience of older women living with loneliness and chronic conditions in Appalachia. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 39(2), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000029

- Verhagen, M., Lodder, G. M. A., & Baumeister, R. F. (2018). Unmet belongingness needs but not high belongingness needs alone predict adverse well-being: A response surface modeling approach. Journal of Personality, 86(3), 498–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12331

- Voelkl, K. E. (1995). School warmth, student participation, and achievement. The Journal of Experimental Education, 63(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1995.9943817