ABSTRACT

Background

The 2018 Phoenix Australia Clinical Practice Guidelines for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) recommended that practitioners use validated, user-friendly self-report measures for PTSD in their practice. However, selecting which measure to use can be difficult as there are currently no guidelines for selection. This research sought to evaluate self-report outcome measures for adults with PTSD and produce recommendations to guide clinicians.

Method

A systematic search was use qd to identify relevant articles and a comprehensive list of the existing measures of PTSD symptoms were extracted. A second search for validation papers for these measures was then conducted. Using these validation papers, measures were evaluated for their psychometric properties and utility for clinical practice via a purpose-built evaluation tool.

Findings

Twenty-two self-report outcome measures for PTSD were extracted from 256 randomised controlled trials. For these measures, 110 validation papers were located. For nonspecific trauma exposure populations, the PCL-5 and SPRINT were found to be the most psychometrically valid measures, with the highest scoring clinical utility. The measures for 12 specific trauma exposure populations were examined and discussed.

Conclusion

This paper has direct clinical relevance for working with individuals with PTSD and provides researchers and clinicians with justification for outcome measure selection.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

It is recommended that clinicians use validated, user-friendly self-report measures to support their assessments of treatment outcomes over time for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Clinicians may struggle to select which measure to use in their practice when faced with a plethora of choice regarding outcome measures for PTSD, especially given the impact of the DSM-5 update.

The differences between measures which are utilised frequently (i.e. ‘common’ measures) and measures with good psychometric properties (i.e. validated measures) and those with good clinical utility (i.e. usability) can be difficult to understand

What this topic adds:

This paper used systematic review methodology was used to identify & evaluate a comprehensive list of self-report outcome measures for PTSD since the DSM-5 update in 2013 and the populations that they should be used with.

For non-specific trauma exposure populations, the PCL-5 and SPRINT were found to be the most psychometrically valid measures, with the highest scoring clinical utility.

The most psychometrically valid measures, with the highest scoring clinical utility for twelve specific trauma exposure populations are also presented.

Introduction

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a psychological condition that has been included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) since 1980 (American Psychiatric Association, Citation1980). The definition, diagnostic criteria, and symptomatic criterion of PTSD have changed significantly with each edition (Pai et al., Citation2017). In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association introduced the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), and in 2018 the World Health Organisation introduced the ICD-11 (World Health Organisation, Citation2018) with both including significant changes regarding PTSD. In response to the changes in PTSD criterion, the predictive/screening tools, diagnostic tools, and outcome measures for PTSD must be updated to reflect these changes (Clark et al., Citation2017).

The 2018 Phoenix Australia Clinical Practice Guidelines for PTSD recommended that clinicians use validated, user-friendly self-report measures to support their assessments of treatment outcomes over time and provided a short list of the most frequently used measures (Phoenix Australia – Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health, Citation2018). However, there needs to be consideration given to the differences between measures, which are utilised frequently (i.e., “common” measures), those with good psychometric properties (i.e., trustworthiness) and those with good clinical utility (i.e., usability).

Whilst attempts exist to collate the self-report outcome measures for PTSD, few have evaluated usability and trustworthiness to aid with measure selection (E. B. Carlson, Citation1997; Norris & Hamblen, Citation2004; Solomon et al., Citation1996). Norris and Hamblen reviewed 17 outcome measures for their ability to determine symptomology for PTSD (Norris & Hamblen, Citation2004). Former-Hoffman and colleagues extracted 11 PTSD focused outcome measures from 193 randomised controlled trials in their systematic review assessing the psychological and pharmacological treatments for adults with PTSD (Forman-Hoffman et al., Citation2018). Both the 2018 Phoenix Australia Clinical Practice Guidelines for PTSD and the National Center for PTSD provide a list, along with basic validation information, of eight of the most commonly used measures alongside their recommendations (National Center for PTSD, Citation2018; Phoenix Australia – Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health, Citation2018). Only Norris and Hamblen (Citation2004) review assessed clinical utility alongside psychometric properties, with measures evaluated for their reliability and validity with commentary provided on their quality. However, no guide for measure selection was suggested and the review requires updating to reflect the DSM-5, which was unavailable at the original time of publication.

As such, this study aimed to use a systematic search strategy to produce a comprehensive list of the self-report outcome measures for PTSD utilised in literature since the introduction of the DSM-5 in 2013 and evaluate these measures within their validation populations.

Method

This study aimed to answer the following research question: Which self-reported outcome measures are best for clinicians and researchers when working with adults with PTSD?

Overview of search and evaluation processes

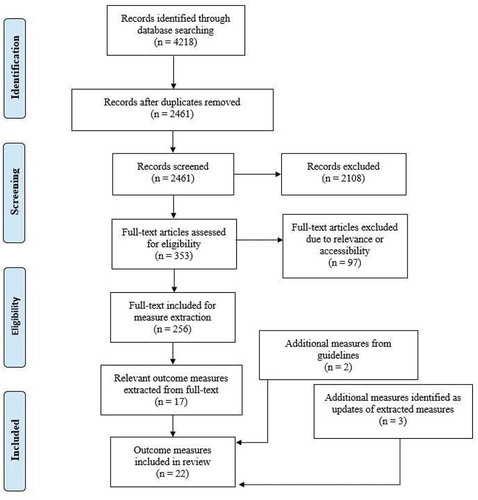

The search and evaluation included three stages: 1) identifying self-reported outcome measures; 2) searching for validation papers of these measures; 3) performing a methodological evaluation of the identified measures using a custom-built evaluation tool. outlines the flow of this process.

Stage one: identifying the self-reported PTSD outcome measures

A systematic search was performed to identify self-report measures of PTSD. The Cochrane Library, Medline©, EMBASE© and PsycInfo© databases were reviewed from 1st of January 2013 until 17th of January 2019. The population was adults with PTSD, the context was any intervention specific to PTSD, and the concept was assessing for any outcome related to PTSD. Keywords included adjustment disorder, combat disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychological trauma, stress disorders, traumatic, psychotrauma, post-traumatic stress. The MeSH, keyword search terms and Boolean operators were modified to accommodate each search database. Results were limited to adult, English language, randomized controlled trial, clinical trial, controlled trial, and from 2013 onward. Reference lists of included articles were manually searched. After removing duplicates, one author (HB) assessed titles and abstracts for eligibility. Studies were eligible if they: contained an intervention for PTSD for adults which utilised a self-reported outcome measure; were prospective study designs (e.g., clinical trials, randomised controlled trials (RCT), and quasi-randomised controlled trials); were published in a peer-reviewed journal after 2013, accessible in full text and written in English. Research was excluded if the data included were a re-analysis of an existing included study.

In addition to this search, the Phoenix Australia clinical practice guidelines and the National Centre for PTSD practice guidelines for PTSD treatment were also reviewed to identify any additional measures. It was expected that randomised trials, controlled trials, and clinical practice guidelines would capture a comprehensive selection of self-report assessments for PTSD and that tools used in these trials and guidelines would have been rigorously developed and representative of high-quality assessments of PTSD based on a previously documented similar process to identify and appraise the properties of assessments used to evaluate functional abilities in older adults (Wales et al., Citation2016).

Eligibility for inclusion as a self-report measure of PTSD

For each paper, data were independently extracted by one author (HB). Data extracted included author and date, study design, and outcome measures collected.

Measures were included in this study if they were:

Self-report outcome measures which assessed the symptomology of PTSD

A stand-alone measure (e.g., not part of larger symptom inventories)

Were reported in a study that assessed an intervention for PTSD between 2013 and 2019; or an updated/revised version of a reported measure; or were recommended in the 2018 clinical practice guidelines or by the National Centre for PTSD.

Measures were not included if they were a screening/predictive tool, utilised as a diagnostic tool, or were clinician administered.

Many self-report outcome measures which assessed the symptomology of PTSD from DSM-III have been updated for later DSM models, or they are no longer reflective of PTSD symptomology, such as the Penn Inventory (Scragg et al., Citation2001), which is more reflective of the general change in mental health. Measures such as the Purdue PTSD Questionnaire (Figley, Citation1989) have not been updated since before 2000 are no longer reflective of PTSD symptomology. Therefore, these measures were excluded. Assessment tools were categorised via the trauma-exposure populations within the validation papers. These trauma-exposure populations were either trauma-specific (e.g., population shared a trauma-exposure) or non-specific (e.g., population consisted of individuals with multiple types of trauma-exposure background or were considered to have “general” trauma-exposure, not linked to any singular exposure source).

Stage two: self-reported PTSD outcome validation paper search

An additional search was performed for validation papers on included measures using the keywords valid* OR reliabl* OR psychomet* OR util* in combination with each outcome measure in PTSDpubs and Health and Psychosocial Instruments on 24 May 2019. One author (HB) assessed titles and abstracts and full text of the search for relevance based on the eligibility criteria. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they performed psychometric testing for one of the included outcome measures, were accessible in full-text, and were written in English; no date restrictions were applied.

Stage three: scoring the psychometric properties and clinical utility of included measures

The psychometric properties and clinical utility of the PTSD measures were scored on a purpose-built 19-item checklist. The checklist was based upon the Ready Reckoner checklist (Grimmer-Somers et al., Citation2009) developed by the International Centre for Allied Health Evidence, for evaluating outcome measures to recommend measure selection for clinical practice. This tool was modified for self-report outcome measure assessment by removing the scoring for test re-test properties, as the original tool was designed for the critique of clinician-delivered assessment instruments for patients with persistent pain (Grimmer-Somers et al., Citation2009).

The psychometric property criteria were developed in consideration of the most important elements to determine the trustworthiness of a measure for repeated practice, i.e., evidence of validity testing, evidence of reliability testing and ability for the clinician to trust outcome results (Grimmer-Somers et al., Citation2009). Clinical utility criteria were developed in consideration of what factors impact clinical practice when selecting an outcome measure. These are possible comprehension constraints, time taken to complete, availability of comparative scores, and accessibility to the clinician (Grimmer-Somers et al., Citation2009). Each criterion was scored yes = 1, no or unclear = 0 with a maximum quality score of 19/19 for all criteria, 11/11 for psychometric properties and 8/8 for clinical utility. The Ready Reckoner does not provide a cut-off or indication of whether a measure is above a threshold for recommendation, but instead serves as a guide of the most important information for clinicians to consider in relation to their specific clinical context. Refer to the supplementary materials for a copy of the checklist assessment tool and scoring criteria.

To ensure that appropriate scores were provided for each outcome measure, assessments were performed under two categories: an overall assessment, which considered the validation of the measure for “mixed/general/non-specified trauma”; and a population-specific assessment, which considered the validation population and the influence of differing types of trauma.

Scoring of the psychometric properties and clinical utility was performed by one author (HB) and a randomised sample of measures was double coded by additional authors (AB, JK, MP, KB) to ensure the appropriateness of coding. Full consensus was reached through discussion.

Results

Study selection

Stage one: identifying self-reported PTSD outcome measures

The database search yielded 4218 potentially relevant articles, including 2461 unique citations after duplicates were removed. Of these, 353 underwent full-text review, with 256 studies meeting the eligibility criteria. Reasons for exclusion were mostly: not being a controlled trial, the data were a re-analysis of the results of an RCT, contained children, did not focus on PTSD, the full-text was not available, the article was not available in English, or was a currently ongoing clinical trial. Within the 256 RCTs, 17 patient-reported outcome measures for PTSD were reported. Additional two measures (DAPS & M-PTSD-C) were recommended measures reported in the clinical practice guidelines, and an additional three (DAPS-II, PDS-5, and TSI-II) were located as updates of existing measures to reflect the DSM-5. See for the frequency of use for these measures across the studies and for the search selection process.

Table 1. Characteristics of included self-report outcome measures for PTSD

Stage two: self-reported PTSD outcome validation paper search

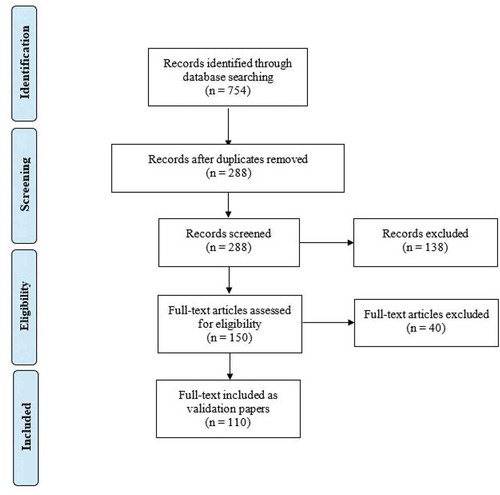

The validation search yielded 754 potential articles, including 288 unique citations after duplicates were removed. Of these, 150 underwent full-text review, with a total result of 110 studies. Relevant outcome measure papers were hand searched for any additional papers. See .

Stage three: scoring the psychometric properties and clinical utility of included measures

Characteristics of outcome measures

Characteristics and abbreviations of the identified outcome measures are presented in .

A total of 22 self-report outcome measures for PTSD were included in this study. The PTSD Checklist (Civilian) was utilised the most in 52 papers in the literature. Most measures were utilised across a wide array of trauma exposure populations and been translated into multiple languages. However, many of these measures were not validated in the populations in which they have been used – often a measure was validated in a single population group, and then used across multiple population groups without additional validation studies being performed.

Assessment and scoring

Overall scores of the included outcome measures are presented in , with population-specific scores of the included outcome measures shown in . A breakdown of the scoring results for each scale is available in the supplementary materials. Given that many of the measures covered in this study have been used in many populations, but only validated in certain populations, it is important to separate measures to clarify which measures have undergone validation in specific populations. As such, some measures will not be present in , as they have never been validated with a general population or a non-specific population. Similarly, some measures will not be present in , as they have never been validated with a specific population group. See the supplementary materials for the detailed checklist assessment results, including a breakdown of validity, reliability, norms and cut off scores.

Table 2. Overall scores of the outcome measures where the validation population was made up of non-specific or multiple kinds of trauma-exposure populations

Table 3. Validated outcome measures by trauma-exposure population

Validation in mixed or non-specific trauma exposure populations

When the outcome measures are considered broadly, only 13 of the 22 outcome measures had been validated in mixed (being validation population made up of multiple kinds of trauma-exposure populations) or non-specific trauma populations. No single measure fulfilled all the psychometric or clinical utility quality criteria, and all were generally of moderate to high quality. For psychometric properties, most measures had good face and content validity, and excellent internal consistency. However, many of the outcome measures did not have a recorded minimal clinically important difference (MCID), and many have not been assessed for their discriminant validity. For clinical utility, most measures were highly rated. A majority of the measures utilised short, simply worded instructions, were able to be scored manually, and were freely available to both access and to use. However, few measures had been assessed with a general population to provide normative data, and cut-off scores were not always provided.

Of the 13 outcome measures which were validated with non-specified trauma populations, the PCL-5 and the SPRINT are the highest scoring measures, with both meeting all criteria except assessment for MCID.

Validation in specific trauma exposure populations

As seen in , when considering the differing trauma-exposure populations, it was found that the 22 included measures had been validated across 12 trauma-exposure populations, as provided by the populations listed in the validation papers. These included Emergency Services; Illness and Hospitalisation; Maternity; Migrants; Military, War and Combat-related; Motor Vehicle Accidents; Natural Disasters; Prison; Refugees and Asylum Seekers; Sexual and Domestic Violence; Substance Abuse; and Victims of Crime. It should be noted that while the migrant population sits under its own category, most of the migrant populations examined within this validation group were migrating from politically unstable countries. It is likely that this population was exposed to war-related/persecutory trauma, and as such the measures for this population group (PCL and PCL-5) are likely to be relevant to refugee populations also.

No singular measure was validated in all 12 trauma-exposure populations. Many measures were validated in multiple languages within each population. The PCL-C was the most versatile measure, having been validated in six of the 12 trauma populations in this study, and being the recommended measure for three of these populations.

provides the scores for the measures which have been specifically validated within these trauma-exposure population, with a detailed breakdown of scores available in the supplementary materials. The highest scoring recommended measure for each population is highlighted in bold in this table.

Discussion

In summary, this paper aimed to produce a list of the self-report outcome measures for PTSD and to provide recommendations on outcome measure selection for clinicians and researchers when working with adults with PTSD. As such, for non-specific trauma, the use of the PCL-5 and the SPRINT is recommended, with recommendations for each of the 12 trauma populations highlighted in .

When considering this study in comparison to previous reviews, there was a considerable increase in the number of outcome measures identified. Previous reviews evaluating outcome measures identified between eight and 17 measures compared to the 22 located for this study (E. B. Carlson, Citation1997; Forman-Hoffman et al., Citation2018; Norris & Hamblen, Citation2004; Solomon et al., Citation1996). This may reflect the development of new measures over time or the systematic nature of the search process used in this study. When unpacking the measures that were found, there is consistency across previous research in that the most frequently reported measures in the literature, being the various PCL measures, IES-R, PDS and PSS-SR, appeared in the other publications and on recommendation lists (Forman-Hoffman et al., Citation2018; National Center for PTSD, Citation2018; Norris & Hamblen, Citation2004).

Unlike previous reviews in the area, we used the Ready Reckoner to formally evaluate relevant outcome measures. Scoring psychometric properties and clinical utilisation allow clinicians to easily select the most valid and utilisable measure for their clinical practice considering their specific purpose and context. While the recommended measures for each trauma population are the highest scoring on our tool (seen in ), it is important for clinicians and researchers to critically consider their needs when making a final selection of a measure and justifying its use. Importantly, this guide cannot, and should not, replace clinical experience and expertise. Language, comprehension, acceptability, resources, management requirements and other factors related to clinical context should all influence selection considerations.

Trauma screening tools, focusing on exposure to differing trauma types, such as the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ) (Kubany et al., Citation2000) or the Traumatic History Questionnaire (THQ) (Hooper et al., Citation2011) could serve as guides for clinicians when selecting a measure. Once the type of trauma that the patient has been exposed to has been determined, clinicians will be able to easily review the self-report outcome measure that scored the highest for that population and utilise that measure to monitor/evaluate treatment. This study also shows that, in-line with recommendations from previous literature, there is a need for the self-report outcome measures captured within this study to undergo validation with additional population groups (Norris & Hamblen, Citation2004).

The PCL-C was the most frequently utilised measure, which appears to be in line with its good psychometric properties and clinical utility across the widest range of validation populations. However, one reasoning for this is that studies which examined the “PCL” and PCL-C were categorised together, as the PCL-C is commonly referred to as “PCL”. Therefore, studies which utilised the PCL-M or PCL-S but did not specify which checklist was utilised (instead only referring to utilising the “PCL”) were recorded as PCL-C. This may, therefore, not be a true reflection of the frequency of use for the PCL-C.

Within the trauma population breakdown, it is important to consider not only the highest scoring measure, but the breakdown scores for psychometric properties and clinical utility when making decisions regarding measure selection. For example, while the IES-R is the recommended measure for refugee and trauma populations, the HTQ was the more psychometrically valid measure, having been validated in multiple languages. Clinically, however, the HTQ is very long and has associated costs. Therefore, the HTQ may be more useful for research purposes due to its robust psychometric properties, whereas the IES-R may be more useful from a practicality standpoint.

When addressing diagnostic criteria changes, only four measures (PCL-5, PDS-5, DAPS-II, and TSI-2) have been updated to align with the changes in the DSM-5. Two (DAPS-II and TSI-2) were not found in either the recent literature nor were any validation studies for these measures located. It is possible that validation studies for these measures are currently underway or have not been published at this time, explaining their absence. This presents a unique challenge for clinicians when selecting self-report outcome measures, as they are forced to choose between well-validated and reliable measures which no longer map to the DSM criteria; or five measures which map to the DSM criteria but that may not suit their specific needs for clinical utilisation, may not be as validated and reliable as older measure choices, and may not be as familiar to the clinician given their relatively new development. The results of this study indicate that the PCL-5 would serve as the current most appropriate choice for clinicians facing this issue, as it maps to the current DSM criteria, and is the recommended choice for exposure to differing trauma types.

That noted, all the included self-report outcome measures assess PTSD symptomology and can be mapped to the post-traumatic stress (PTS) symptomatic criteria to varying degrees. Higher scoring measures may be particularly useful for research studies or clinical practice which does not require a diagnosis of PTSD but will instead be addressing or mapping PTS symptoms. Additionally, this may be particularly useful in clinical settings after diagnosis, as a benchmark of symptom change over time, where criterion mapping may hold less importance. As the diagnostic and symptomatic criterion of PTSD in the DSM-5 is still undergoing validation in accordance with the changes in 2013, the use of measures which are highly valid and related to symptomology, rather than current diagnostic criteria, may still be a valid choice within both clinical practice and research studies.

Limitations and future directions

This study acknowledges several limitations. Firstly, while the search strategy utilised was designed to allow for a comprehensive list of the self-report outcome measures to be identified and evaluated for assessment, it is by no means exhaustive. Within this, it should be noted that only one author screened articles to identify outcome measures from the RCTs. As such, measures and validation studies may have been missed, including those recorded in non-English language papers.

Secondly, measures which have a cost to access (e.g., the Detailed Assessment of Posttraumatic Stress (DAPS) and Trauma Symptom Inventory (TSI)) are not utilised in the literature as often as their fee-free counterparts and their practice manuals were not purchased. This is reflective of the fact that the average clinician would not purchase an outcome measure to investigate its appropriateness unless they knew it was a measure they would utilise. Additionally, it indicates that the psychometric properties for these measures may have not been assessed independently, outside of the measure creators. As such, levels of validity and reliability may be higher than reported in peer-reviewed literature, but lack of reporting has resulted in lower scores on the checklist.

Thirdly, while many measures were validated in multiple languages, the focus of this study was on trauma-exposure populations, rather than language or physical location validation. As such, some populations utilised versions of included outcome measures which were not in English. Additionally, cultural influences due to the physical location of the validation may have influenced scoring regarding trauma exposure. It is recommended that additional studies break-down recommendations by language and country to guide practice internationally.

Fourthly, this paper also does not consider measures which map against the ICD-11, rather, focusing on the changes within the DSM-5. While this was not a goal of this paper, we acknowledge this may be considered a limitation. In a similar vein, these results are limited to PTSD specific measures and not measuring other potential trauma psychological sequelae. An examination of self-report measures (e.g., depression, anxiety, and stress) is recommended to provide guidelines for measure selection to examine potential comorbidities.

Finally, many measures included in this study did not examine the MCID within their validation procedures, scores which indicate the minimal amount of change a person must experience over time for that change to be clinically significant. Without a comprehensive understanding of MCID for these measures, clinicians are beholden only to cut-off scores. While a patient may have moved between cut-off scores, this change may not represent a clinically significant change for that scale. Future validation studies should consider MCID within their psychometric testing.

Conclusion

Based on our identification and evaluation of measures, this paper recommends the use of the PCL-5 and the SPRINT self-report outcome measures for clinicians and researchers when working with adults with PTSD with exposure to differing trauma. Recommendations for outcome measures are made for 12 trauma populations. These recommendations are based upon the psychometric properties and clinical utility of 22 self-report outcome measures when considering the validating population. These findings have immediate and direct clinical applications for individuals with PTSD and can be used to inform both clinical decision-making and research practice.

Contributors

HBS performed the searches, article selection, and data extraction with validation confirmations made by KB, JK, AB, MP. HBS wrote the first draft of the report with input from KB, JK, AB, MP.

Supplemental Material 1

Download MS Word (26.7 KB)Supplemental Material 2

Download MS Excel (43.4 KB)Disclosure statement

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1893615.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Association.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Blanchard, E. B., Jones-Alexander, J., Buckley, T. C., & Forneris, C. A. (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behavior Research & Therapy, 34(8), 669–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

- Bliese, P. D., Wright, K. M., Adler, A. B., Cabrera, O., Castrol, C. A., & Hoge, C. W. (2008). Validating the primary care posttraumatic stress disorder screen and the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist with soldiers returning from combat. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.272

- Briere, J. (1995). The trauma symptom inventory professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Briere, J. (1996). Psychometric review of the trauma symptom checklist-40. In B. H. Stamm (Ed.), Measurement of stress, trauma, and adaptation(pp. 373–376). Sidran Press.

- Briere, J. (2001). Detailed assessment of posttraumatic stress: DAPS: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Briere, J. (2011). Trauma symptom inventory-2 professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Carlson, E. (2001). Psychometric study of a brief screen for PTSD: Assessing the impact of multiple traumatic events. Assessment, 8(4), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/107319110100800408

- Carlson, E. B. (1997). Trauma assessments: A clinician’s guide. Guilford Press.

- Clark, L., Cuthbert, B., Lewis-Fernández, R., Narrow, W., & Reed, G. (2017). Three approaches to understanding and classifying mental disorder: ICD-11, DSM-5, and the National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). Psychological Science In The Public Interest, 18(2), 72–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100617727266

- Connor, K., & Davidson, J. (2001). SPRINT: A brief global assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 16(5), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004850-200109000-00005

- Davidson, J. R., Book, S. W., Colket, J. T., Tupler, L. A., Roth, S., David, D., Hertzberg, M., Mellman, T., Beckham, J. C., Smith, R. D., & Davison, R. M. (1997). Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291796004229

- Falsetti, S. A., Resnick, H. S., Resick, P. A., & Kilpatrick, D. (1993). The modified PTSD symptom scale: A brief self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder. The Behavioral Therapist, 16, 161–162.

- Figley, C. (1989). Purdue PTSD scale. Purdue University.

- Foa, E., Cashman, L., Jaycox, L., & Perry, K. (1997). The validation of a self-report measure of PTSD: The posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychological Assessment, 9(4), 445–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.9.4.445

- Foa, E. B., McLean, C. P., Zang, Y., Zhong, J., Powers, M. B., Kauffman, B. Y., Rauch, S., Porter, K., & Knowles, K. (2016). Psychometric properties of the posttraumatic diagnostic scale for DSM–5 (PDS–5). Psychological Assessment, 28(10), 1166. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000258

- Foa, E. B., Riggs, D. S., Dancu, C. V., & Rothbaum, B. O. (1993). Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post‐traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(4), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490060405

- Grimmer-Somers, K., Vipond, N., Kumar, S., & Hall, G. (2009). A review and critique of assessment instruments for patients with persistent pain. Journal of Pain Research, 2, 21. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S4949

- Hoffman, V., Middleton, J. C., Feltner, C., Gaynes, B. N., Weber, R. P., Bann, C., Viswanathan, M., Lohr, K. N., Baker, C., & Green, J. (2018). Psychological and pharmacological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review update. In Comparative effectiveness review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality No. 207. AHRQ Publication No 18-EHC011-EF. PCORI Publication No. 2018-SR-01.

- Hooper, L. M., Stockton, P., Krupnick, J. L., & Green, B. L. (2011). Development, use, and psychometric properties of the trauma history questionnaire. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 16(3), 258–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2011.572035

- Horowitz, M., Wilner, N., & Alvarez, W. (1979). Impact of event scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 41(3), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004

- Hovens, J. E., Van der Ploeg, H. M., Bramsen, I., Klaarenbeek, M. T. A., Schreuder, J. N., & Rivero, V. V. (1994). The development of the self‐rating inventory for posttraumatic stress disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 90(3), 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01574.x

- Keane, T. M., Caddell, J. M., & Taylor, K. L. (1988). Mississippi scale for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Three studies in reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.56.1.85

- Kubany, E. S., Leisen, M. B., Kaplan, A. S., Watson, S. B., Haynes, S. N., Owens, J. A., & Burns, K. (2000). Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The traumatic life events questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 12(2), 210. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.210

- Mollica, R. F., Caspi-Yavin, Y., Bollini, P., Truong, T., Tor, S., & Lavelle, J. (1992). The Harvard trauma questionnaire: Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180(111), 6. https://doi.org/10.1037/t07469-000

- National Center for PTSD. (2018) List of all measures, US Department of Veterans Affairs, USA. US Department of Veterans Affairs. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/list_measures.asp

- Norris, F. H., & Hamblen, J. L. (2004). Standardized self-report measures of civilian trauma and PTSD. In J. P. Wilson & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 63–102). The Guilford Press.

- Norris, F. H., & Perilla, J. L. (1996). The revised civilian mississippi scale for PTSD: Reliability, validity, and cross-language stability. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(2), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02110661

- Pai, A., Suris, A., & North, C. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, change, and conceptual considerations. Behavioral Sciences, 7(4), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7010007

- Petri, J. (2017). The Detailed Assessment of Posttraumatic Stress, (DAPS-II): Initial psychometric evaluation in a trauma-exposed community sample [Masters Thesis]. Auburn University.

- Phoenix Australia - Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health. (2018). Australian guidelines for the treatment of acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Phoenix Australia.

- Scragg, P., Grey, N., Lee, D., Young, K., & Turner, S. (2001). A brief report on the Penn inventory for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 14(3), 605–611. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011120925521

- Solomon, Z., Keane, T., Newman, E., & Kaloupek, D. (1996). Choosing self-report measures and structured interviews. In E. B. Carlson (Ed.), Trauma research methodology (pp. 56–81). Sidran Press.

- Wales, K., Clemson, L., Lannin, N., & Cameron, I. (2016). Functional assessments used by occupational therapists with older adults at risk of activity and participation limitations: A systematic review. PloS One, 11(2), e0147980. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147980

- Weathers, F., Litz, B., Herman, D., Huska, J., & Keane, T. (1993, October). The PTSD checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility [Paper presentation]. Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX, USA.

- Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (1997). The impact of event scale-revised. In J. P. Wilson & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 399–411). Guilford.

- World Health Organisation. (2018). ICD 11 - International classification of diseases and health related problems: Eleventh revision. World Health Organisation.